Summary

Epithelial integrity and barrier function must be maintained during the complex cell shape changes that occur during cytokinesis in vertebrate epithelial tissue. Here, we investigate how adherens junctions and bicellular and tricellular tight junctions are maintained and remodeled during cell division in the Xenopus laevis embryo. We find that epithelial barrier function is not disrupted during cytokinesis and is mediated by sustained tight junctions. Using FRAP, we demonstrate that adherens junction proteins are stabilized at the cleavage furrow by increased tension. We find that vinculin is recruited to the adherens junction at the cleavage furrow, and inhibiting recruitment of vinculin by expressing a dominant negative mutant increases the rate of furrow ingression. Furthermore, we show that cells neighboring the cleavage plane are pulled between the daughter cells, making a new interface between neighbors, and two new tricellular tight junctions flank the midbody following cytokinesis. Our data provide new insight into how epithelial integrity and barrier function are maintained throughout cytokinesis in vertebrate epithelial tissue.

Keywords: cytokinesis, adherens junctions, tight junctions, tricellular tight junctions, epithelial barrier function, Xenopus laevis, FRAP, contractile rings, vinculin

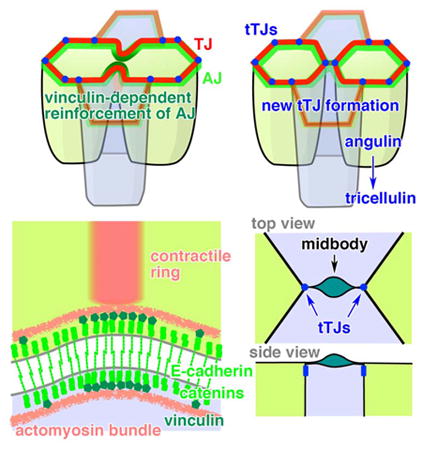

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Polarized epithelial cells make epithelial sheets and maintain tissue homeostasis by serving as barriers that separate distinct compartments in the body. Cells in epithelial sheets exhibit high rates of turnover, and the number of dying cells must be balanced by the number of dividing cells [1]. Remarkably, epithelial cells maintain barrier function even as they undergo major shape changes during cell division, extrusion, or intercalation [2]. Cell-cell junctions are essential for maintaining epithelial integrity and barrier function of epithelial sheets during homeostasis and morphogenesis.

The vertebrate apical junctional complex consists of tight junctions (TJs), adherens junctions (AJs) and desmosomes [3-5]. Connections to the actomyosin cytoskeleton are important for the structural integrity and regulation of both TJs and AJs [6]. TJs seal the intercellular spaces between adjacent cells and form a selective, regulated barrier. TJs consist of claudin-mediated TJ strands [7] and cytoplasmic plaque proteins including ZO-1, which bind to the cytoplasmic tail of claudins [8] and link TJs to actin. A specialized type of TJ, the tricellular tight junction (tTJ), forms at vertices where three cells come together and is comprised of two known unique protein components in vertebrate epithelial cells: tricellulin and angulin family proteins [9-11]. AJs mediate cell-cell adhesion and are important for epithelial tissue integrity, which is challenged when cells undergo shape changes [12]. AJ structure is dependent upon E-cadherin; its extracellular domain mediates strong adhesion between adjacent cells, while its cytoplasmic tail is associated with the cytoplasmic plaque proteins β-catenin and α-catenin [13, 14]. AJs can be linked to actin via α-catenin [15], as well other proteins, some of which help reinforce cell adhesion against mechanical stress [16-19].

Until recently, cell-cell junctions were considered stable, heavily crosslinked structures. However, fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) experiments in cultured epithelial cells demonstrated that while overall junction structure is maintained at steady state, individual TJ and AJ proteins are, in fact, highly dynamic [20-22]. Importantly, changes in the dynamics of individual junction proteins can regulate epithelial function [23]. This plasticity of cell-cell junction structure is likely important for maintenance of barrier function when cells undergo dramatic shape changes during morphogenesis or cell division.

Cell division helps shape the organization of epithelial tissues by generating a new cell interface and two new cell vertices with each cell division [2, 24]. During cytokinesis, an actomyosin-based contractile ring is formed at the cell equator and generates force to physically separate one cell into two daughter cells [25, 26]. In epithelial cells, both the dividing cell and its neighboring cells undergo drastic shape changes, and, accordingly, cell-cell junctions must be dynamically reorganized. Pioneering work using electron or immunofluorescence microscopy in fixed epithelial tissues or cultured epithelial cells reported that cell-cell junctions are maintained throughout cytokinesis [27, 28]. However, junction maintenance and remodeling during cytokinesis has not been investigated in live vertebrate epithelial tissues, and it remains unclear how epithelial cells maintain barrier function and epithelial integrity while at the same time dynamically changing shape during cytokinesis.

In this study we used live cell imaging of fluorescently tagged junctional proteins in the epithelium of gastrula-stage Xenopus laevis embryos to investigate how cell-cell junctions, including TJs, tTJs, and AJs, are maintained and remodeled during cytokinesis. Further, we examined how tension generated by the contractile ring affects the stability of AJ proteins and identified a mechanism that strengthens the AJ at the cleavage furrow. Together, these studies shed new light on how barrier properties are maintained in proliferating vertebrate epithelial tissues.

Results

Epithelial barrier function is maintained during vertebrate epithelial cytokinesis

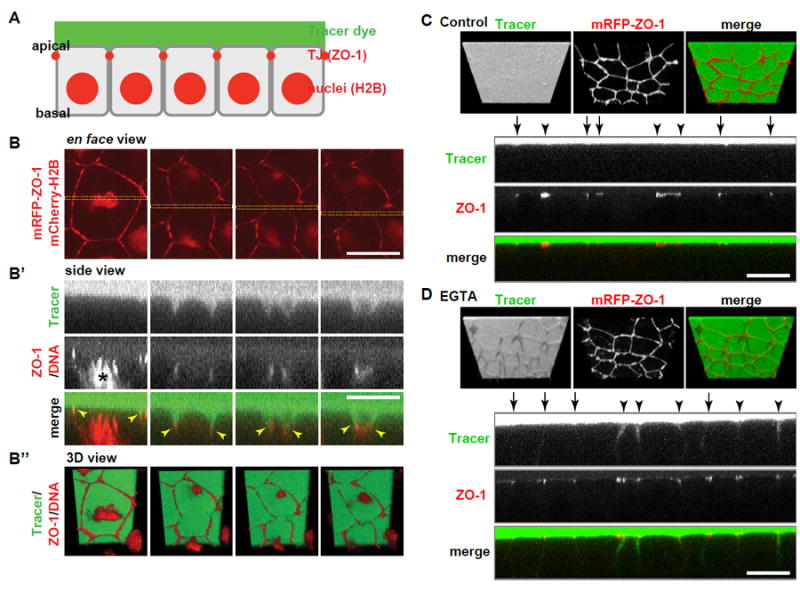

Although it has been suggested that epithelial barrier function is maintained throughout cytokinesis [27, 28], there has been no direct evidence in live cells. Here, we evaluated the barrier function of an intact epithelial sheet containing dividing cells by using a fluorescent tracer dye penetration assay. Gastrula-stage Xenopus embryos expressing mRFP-ZO-1 and mCherry-H2B as markers for TJs and chromosomes, respectively, were mounted in medium containing fluorescein and imaged using timelapse confocal microscopy (Figure 1A). In dividing cells, fluorescein was restricted to the apical side of the TJ (Figure 1B; Movie S1). When the barrier function was disrupted by injecting embryos with EGTA, which chelates Ca2+ resulting in AJ disruption and TJ dysfunction [29, 30], fluorescein breached the TJ, spreading to the basolateral side (Figures 1C and 1D; Movie S2). These results indicate that epithelial barrier function is maintained throughout cytokinesis.

Figure 1. Barrier function is maintained during Xenopus epithelial cytokinesis.

A. Experimental setup for fluorescent tracer penetration assay. Gastrula-stage embryos expressing mRFP-ZO-1 (TJs) and mCherry-H2B (chromosomes) were mounted in 0.1X MMR containing 10 μM fluorescein (tracer dye) and observed.

B. Fluorescent tracer penetration assay of a representative dividing cell. Three views of the same region of interest are shown: en face view (B), side view of the region indicated with yellow rectangles in B (B’) and 3D view (B’’). Note that the TJ labeled by mRFP-ZO-1 (red) is initially pulled basally, but fluorescein (green) at apical side (top) does not breach through the TJ (yellow arrowheads in B’) to the basal side (bottom). Time, min:sec. Asterisks in B and at 0:00 in B’ indicate chromosomes (red), which are not visible at other time points in B’. C and D. Embryos expressing mRFP-ZO-1 (red) were injected with 5 nl of 0.1x MMR (C) or 100 mM EGTA (D) into the blastocoel, mounted in 10 μM fluorescein (green) and observed. Upper panels, 3D view; lower panels, side view. Note that fluorescein tracer breaches the TJ in D (EGTA-treated), but not in C (control). Arrows and arrowheads indicate bicellular and tricellular junctions, respectively.

Scale bars, 20 μm.

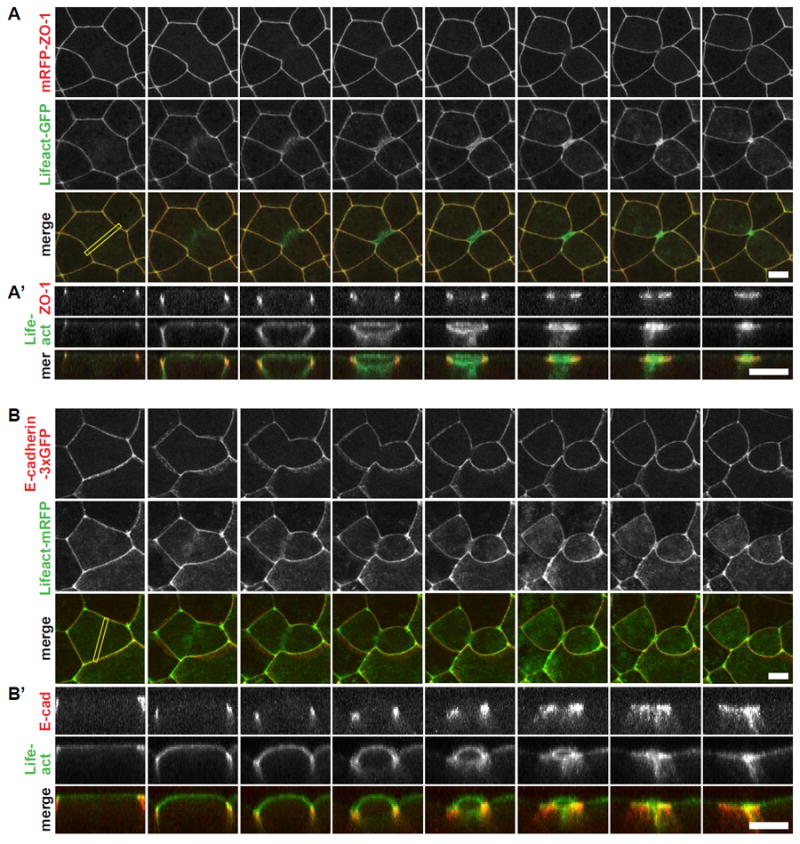

AJs and TJs remain continuous and connected to the contractile ring during cytokinesis

To understand how epithelial cells maintain barrier function during cytokinesis, we investigated how TJs are reorganized during cytokinesis by imaging embryos expressing mRFP-ZO-1 and Lifeact-GFP. Lifeact-GFP binds to F-actin and labels both the actomyosin contractile ring and apical actomyosin at cell-cell junctions (Figure 2A). Before cytokinesis onset, ZO-1 and F-actin were present at cell-cell junctions surrounding the dividing cell, and cortical actin was visible at the apical surface (Figure 2A). The contractile ring formed at the cell equator orthogonal to the junctional plane (Figure 2A). Consistent with previous reports of polarized epithelial cell cleavage [27, 31-33], the contractile ring ingressed anisotropically from basal to apical. Importantly, TJs remained continuous and appeared to be connected to the contractile ring throughout cytokinesis (Figure 2A; Movie S3). We then examined the behavior of AJs during cytokinesis using E-cadherin- (E-cad-) 3xGFP as a probe. Notably, AJs were also unbroken and maintained connection to the ingressing contractile ring throughout cytokinesis (Figure 2B; Movie S4). We conclude that in the Xenopus gastrula epithelium, TJs and AJs remain continuous and connected with the contractile ring during cytokinesis, which likely contributes to maintenance of the epithelial barrier function.

Figure 2. The contractile ring ingresses anisotropically from basal to apical and remains continuous and connected to cell-cell junctions.

A. Live imaging of TJs and the cytokinetic contractile ring in embryos expressing mRFP-ZO-1 (red, TJs) and Lifeact-GFP (green, F-actin). Projected multi-plane en face images (A) and side views at the cleavage plane (A’) (yellow rectangle in the en face view). Note that the cytokinetic ring remains connected to TJs throughout cytokinesis.

B. Live imaging of AJs and the cytokinetic contractile ring in embryos expressing E-cadherin-3xGFP (pseudocolored red, AJs) and Lifeact-mRFP (pseudocolored green, F-actin). Projected multi-plane en face images (B) and side views at the cleavage plane (B’) (yellow rectangle in the en face view). Note that the cytokinetic ring remains connected to AJs throughout cytokinesis. For side views, top is apical, bottom is basal. Scale bars, 10 μm.

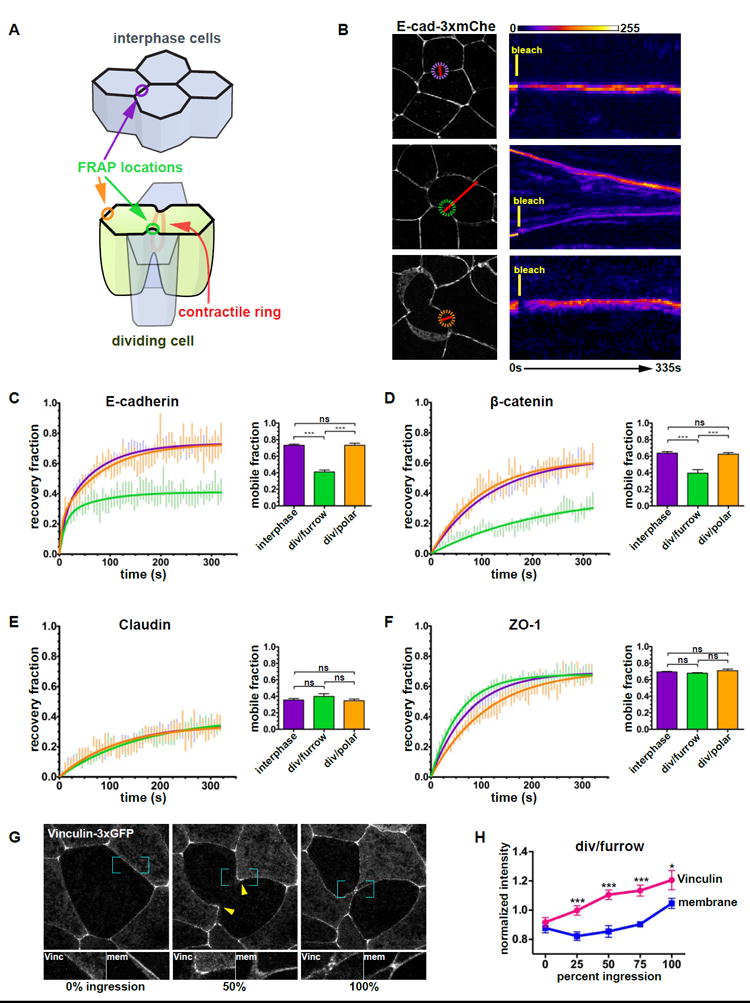

AJ proteins are stabilized and vinculin is recruited to the cleavage furrow of dividing cells

Although the overall structure of TJs and AJs remains intact during cytokinesis and both junctions appear to be connected to the ingressing contractile ring by fluorescence microscopy (Figure 2), it remained unclear whether the tension generated by the contractile ring affected the dynamics of individual junction proteins. To answer these questions, we compared FRAP curves for the AJ proteins E-cadherin (E-cad-3xmChe) and β-catenin (β-catenin-GFP) and the TJ proteins claudin-6 (mCherry-claudin-6) and ZO-1 (mRFP-ZO-1) in interphase cells and dividing cells at both the cleavage furrow and a polar region (Figures 3A and S1A). There were no significant differences in FRAP between interphase cells and the polar region of cells undergoing cytokinesis, indicating that junction protein dynamics are not globally changed in dividing cells (Figures 3B-3F, and S1). Notably, the mobile fraction for E-cadherin was significantly reduced at the cleavage furrow compared with the polar region (41.0 ± 2.2% vs. 73.2 ± 2.6%, respectively; Figures 3B and 3C), indicating that E-cadherin is stabilized at the cleavage furrow. Similar results were observed for β-catenin; the mobile fraction was strongly reduced at the cleavage furrow compared with the polar region (39.5 ± 4.4% vs. 62.4 ± 2.0%, respectively; Figure 3D). In contrast to the AJ proteins, the mobile fractions of claudin-6 and ZO-1 were unchanged at the cleavage furrow compared with the polar region (Claudin, 39.8 ± 3.3% vs. 34.6 ± 2.0%; ZO-1, 67.9 ± 0.7% vs. 70.9 ± 2.0%; Figures 3E, 3F, and S1).

Figure 3. AJ proteins, but not TJ proteins, are stabilized at the cleavage furrow of dividing cells and vinculin is recruited to the cleavage furrow.

A. Diagram depicting locations of FRAP measurements in interphase (purple circle) and dividing cells (green circle: cleavage furrow, orange circle: polar region).

B. Representative examples of E-cadherin-3xmCherry FRAP. Cell images (left) show a frame taken from a time-lapse movie. The colored dashed circles indicate the bleached areas, the red lines indicate the locations used to generate the kymographs (right), and the white asterisks indicate the two daughter cells. A FIRE lookup table was applied to the kymographs; time (horizontal axis) and bleach time points are indicated. Scale bars, 10 μm.

C. E-cadherin-3xmCherry FRAP data fitted with a double exponential curve and graph of average mobile fractions. The number of cells (n) quantified is: interphase cells (n=23), dividing cells/furrow (n=17), dividing cells/polar (n=12).

D-F. FRAP data of β-catenin-GFP (D), mCherry-claudin-6 (E), and mRFP-ZO-1 (F) fitted with a single exponential curve and graph of average mobile fractions. n=21, 19, 14 (D), n=23, 18, 10 (E), and n=34, 34, 21(F).

G. Vinculin-3xGFP in a dividing cell. White asterisks indicate daughter cells, yellow arrowheads indicate accumulation of Vinculin-3xGFP at the cleavage furrow, blue brackets indicate magnified areas of Vinculin-3xGFP and mCherry-membrane shown below the cell view. H. Quantification of Vinculin-3xGFP and mCherry-membrane intensity at the cleavage furrow of dividing cells (n=14).

Error bars, S.E.M. Statistics, unpaired t-test, ***p<0.0001 (C-F), paired t-test, ***p<0.001, *p<0.05 (H).

See also Figures S1 and S2.

Our finding that AJ proteins are stabilized at the furrow during cytokinesis are consistent with previous studies showing that AJ proteins are stabilized under high tension and are more dynamic under reduced tension [13, 34, 35]. We tested this idea in Xenopus embryos by using pharmacological approaches to globally increase or decrease tension (Figure S2). Interphase cells in embryos treated with the phosphatase inhibitor calyculin A, which increases tension [36, 37], exhibited stabilized junctional E-cadherin compared to controls (mobile fraction, 56.1 ± 3.4% vs. 73.5 ± 3.1%; Figure S2A). ZO-1 was stabilized in cells treated with calyculin A (mobile fraction, 62.8 ± 1.0% vs. 75.5 ± 1.2%; Figure S2D) but not at the furrow (Figure 3F), indicating that tension from the ingressing contractile ring is transmitted primarily to the AJ, not the TJ. To reduce tension generated by the contractile ring, we injected embryos with the ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 [38]. E-cadherin was more dynamic at the cleavage furrow in Y-27632 treated cells compared to controls (mobile fraction, 59.3 ± 4.0% vs. 40.3 ± 2.0%; Figure S2B). Treatment with the same concentration of Y-27632 did not affect E-cadherin dynamics in interphase cells compared to controls (mobile fraction, 80.2 ± 2.3% vs. 80.5 ± 1.1%; Figure S2C).

The AJ protein α-catenin is known to act as a tension transducer that senses increased junctional tension generated by pulling forces from adjacent cells and responds by strengthening the junction [13, 16]. High tension induces a conformational change in α-catenin and recruitment of vinculin to AJs [13]. Therefore, we tested whether fluorescently-tagged vinculin is recruited in response to increased junctional tension generated during cytokinesis. Vinculin-3xGFP was significantly increased specifically at the cleavage furrow (Figures 3G, 3H, and S2H-J), while the intensity of a membrane marker (Figures 3G, 3H, and S2G) or α-catenin (Figures S2I, S2K, and S2L) was not. To confirm that vinculin-3xGFP is recruited to AJs in response to increased tension, we increased junctional tension globally in two ways. First, embryos treated with calyculin A exhibited a ~2-fold increase in vinculin-3×GFP recruitment to junctions, while the intensity of E-cad-3xmCherry was unchanged (Figure S2E). Second, upon addition of ATP, which also increases contractility [39, 40], the embryo exhibited contraction within 60 s and a significant increase (~3-fold) in the intensity of vinculin-3xGFP at junctions within minutes (Figure S2F). Together, these results suggest that elevated tension reinforces AJs connected to the contractile ring by increasing the stability of individual AJ proteins and recruiting vinculin to the cleavage furrow.

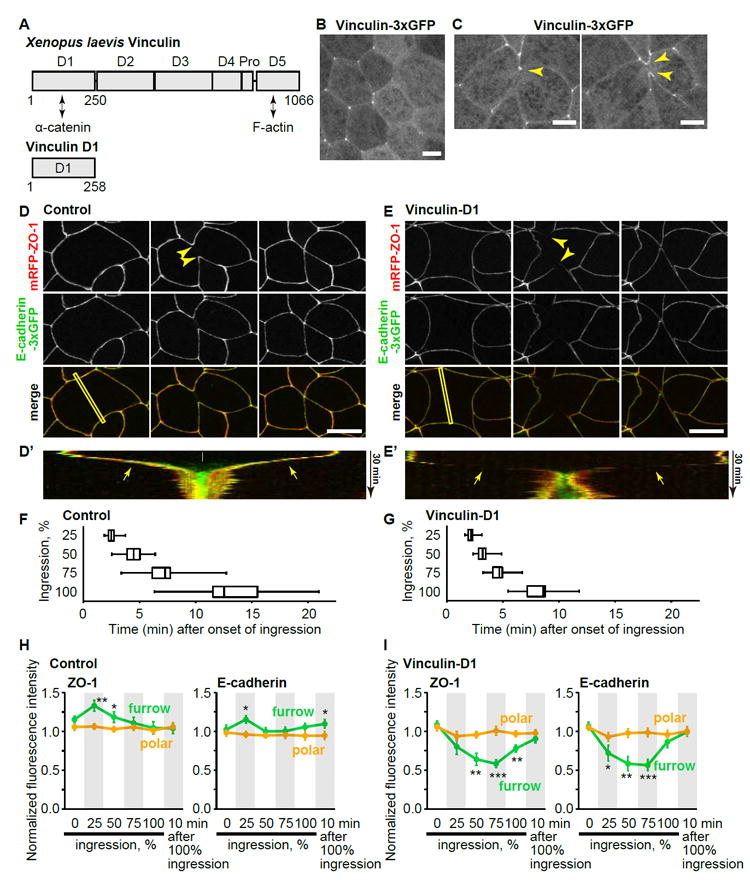

Dominant negative vinculin abolishes cell-cell junction reinforcement at the cleavage furrow and accelerates ingression

To test how reinforcement of AJs at the cleavage furrow, in turn, affects the process of cytokinesis, we perturbed vinculin-mediated AJ strengthening. For this purpose, we developed a dominant-negative vinculin. Vinculin is localized at AJs through interaction of its N-terminal D1 domain with α-catenin under tension, and vinculin recruits F-actin through its C-terminal D5 domain (Figure 4A) [41, 42]. We predicted that overexpression of the D1 domain alone, which localizes at AJs (Figure S3D), would competitively interfere recruitment of full-length vinculin to AJs and might abolish tension-mediated reinforcement of AJs. We tested the dominant negative effect of vinculin D1 by expressing full-length vinculin-3xGFP uniformly and untagged vinculin D1 with an injection marker in a mosaic manner. As predicted, the localization of vinculin-3xGFP at both bicellular and tricellular junctions was drastically reduced in vinculin D1-expressing cells (Figure 4B). The recruitment of vinculin-3xGFP to the cleavage furrow in dividing cells was also abolished when the cell neighboring the cleavage plane expressed vinculin D1 (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. Dominant negative vinculin abolishes cell-cell junction reinforcement at the cleavage furrow and accelerates ingression.

A. Domain structure of Xenopus laevis vinculin. Pro, proline-rich region.

B and C. Live imaging of Vinculin-3xGFP in interphase (B) and dividing (C) cells of embryos expressing vinculin D1 in a mosaic manner. D1 indicates vinculin D1-expressing cells, which are identified with a lineage tracer (mCherry-H2B, not shown). Note that vinculin-3xGFP intensity at bicellular and tricellular AJs is reduced in B, and the localization of vinculin at cleavage furrow (yellow arrowheads) is abolished when the neighbor cell expresses vinculin D1 (white arrowhead). Asterisks in C indicate daughter cells. Scale bars, 10 μm.

D and E. Live imaging of embryos expressing mRFP-ZO-1 (red, TJs) and E-cadherin-3xGFP (green, AJs) without (D) or with (E) expression of vinculin D1. Yellow and white arrowheads show that ZO-1 and E-cadherin are maintained at the cleavage furrow in control cells (D) or reduced in vinculin D1-expressing cells (E), respectively. Scale bars, 20 μm.

D’ and E’. Kymographs of the furrow region shown by yellow rectangles in D and E. Note that E-cadherin (green) completes invagination (white arrow) before ZO-1 (red) in D’ and that both E-cadherin and ZO-1 are maintained (D’) or reduced (E’) at ingressing furrow region (yellow arrows). In E’, two vertices move apart after division (asterisk) because the dividing cell underwent a Type I division (see Figure 7).

F and G. Time that it takes cells to reach 25, 50, 75, and 100% ingression are shown for control (F) and vinculin D1-expressing (G) cells. Whiskers indicate the minimum and maximum, boxes indicate the 25 and 75 percentiles, and vertical line indicates the median. n=12.

H and I. Normalized fluorescence intensity of mRFP-ZO-1 and E-cadherin-3xGFP at the furrow (green) and polar region (orange) in control (H) and vinculin D1-expressing cells (I). n=12. Error bars, S.E.M. Statistics, two-tailed paired Student’s t-test. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.005; ***, p<0.0005.

We examined the effect of vinculin D1 on the behavior of AJs and TJs during cytokinesis by imaging embryos co-expressing E-cad-3xGFP and mRFP-ZO-1 (Figure 4; Movie S5). In control cells, signal intensity for both AJs and TJs was maintained at the cleavage furrow throughout cytokinesis (Figures 4D, 4D’, and S3A). In fact, early in cytokinesis (25% ingression), the intensity of ZO-1 and E-cadherin at the cleavage furrow was slightly but significantly increased compared with a polar region (Figure 4H). In contrast, signal for both AJs and TJs was reduced at the cleavage furrow in vinculin D1-expressing cells (Figures 4E, 4E’, 4I, and S3E), suggesting that inhibition of vinculin localization abolishes the reinforcement of AJs at the cleavage furrow. Furthermore, vinculin D1-expressing cells ingressed much faster than control cells (Figures 4F and 4G), likely due to a lack of counteracting force from the cells neighboring the cleavage furrow. These data indicate that vinculin-mediated AJ reinforcement is involved in maintenance of both AJs and TJs at the cleavage furrow of dividing cells.

We also performed time-lapse imaging of E-cad-3xGFP and mRFP-ZO-1 during cytokinesis, and it revealed that the AJ invaginated faster than the TJ, with the TJ completing invagination around 10 minutes after the AJ (Figure S3A). To confirm these results, we also examined GFP-claudin-6 and E-cad-3xmCherry-expressing embryos (Figure S3B). The invagination of Claudin-6 was also delayed compared with invagination of E-cadherin (Figure S3B). Likewise, when cells in late cytokinesis were examined by immunofluorescence microscopy, endogenous β-catenin had ingressed farther than ZO-1 (Figure S3C). These findings indicate that the AJ completes invagination prior to the TJ.

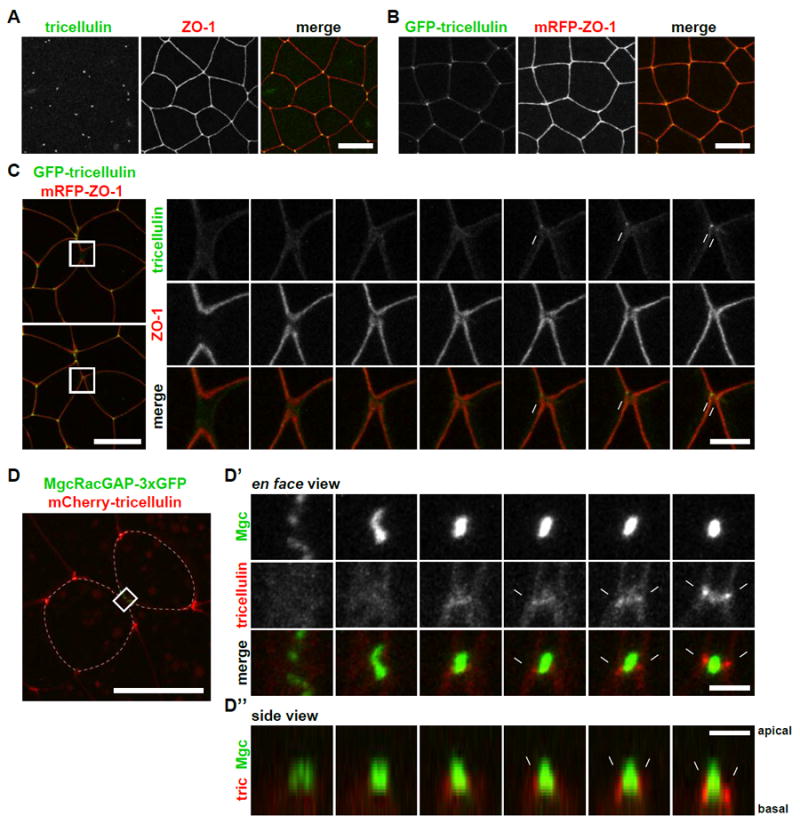

Two nascent tTJs are formed after cytokinesis

tTJs were originally observed by electron microscopy [43-47] and are required for the establishment of strong barrier function in vertebrate epithelial and endothelial cells [9-11, 48]. Here, we investigated for the first time the biogenesis of new tTJs that emerge following cytokinesis. We first examined tricellulin (also known as MarvelD2), a component of tTJs [11]. Immunofluorescence staining showed that tricellulin is expressed in gastrula-stage embryos and localized to tTJs (Figure 5A). GFP-tricellulin also localized to tTJs (Figure 5B). Live imaging of GFP-tricellulin and mRFP-ZO-1 revealed that two tTJs emerge – one followed shortly by another – on either end of a new cell-cell interface that forms between the cells formerly neighboring the cleavage plane (neighbor cells), not the two cells that resulted from division (daughter cells) (Figures S3A and 5C; Movie S6).

Figure 5. Two nascent tTJs are formed after cytokinesis.

A. Immunofluorescence staining of embryos using anti-tricellulin (green) and anti-ZO-1 (red). Scale bar, 20 μm.

B. Live imaging of an embryo expressing GFP-tricellulin (green) and mRFP-ZO-1 (red). Scale bar, 20 μm.

C. Live imaging of a dividing cell expressing GFP-tricellulin (green) and mRFP-ZO-1 (TJs, red). Note that two punctate GFP-tricellulin spots appear at the cell vertices of the new interface between neighbor cells (white arrows). Asterisks and “n”s indicate daughter cells and neighbor cells, respectively. Scale bar, 20 μm (left panels), 5 μm (right panels).

D. Live imaging of a dividing cell expressing MgcRacGAP-3xGFP (midbody, green) and mCherry-tricellulin (tTJs, red) (D). Note that the two tricellulin puncta are located on either side of the midbody in en face views (D’) and can be seen at the basal side of the midbody in side views (white arrows) (D’’). Asterisks and “n”s indicate daughter cells and neighbor cells, respectively. Scale bar, 20 μm (left panels), 5 μm (right panels).

See also Movie S6.

We next examined the relationship of the new tTJs and the midbody, the structure that connects the two daughter cells at the end of cytokinesis and recruits the proteins that promote abscission [25, 26]. We conducted live imaging of mCherry-tricellulin and MgcRacGAP-3xGFP (as a midbody marker) [49, 50] and found that the nascent tTJs were located directly on either side of the midbody (Figure 5D, Movie S6). Side views revealed that the midbody was located at the apical surface of the daughter cells, consistent with previous reports [51], and tTJs formed at the basal side of the midbody (Figure 5D). Taken together, our results indicate that two new tTJs are formed on either side of the midbody immediately after cytokinesis.

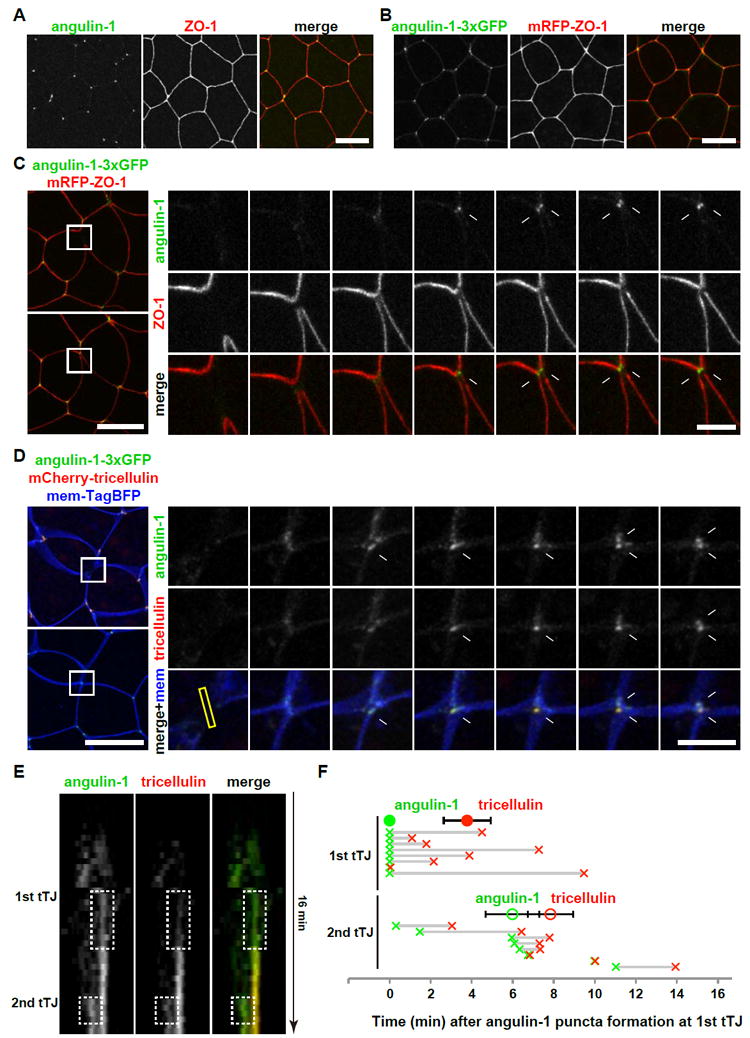

Angulin-1/LSR recruitment to the new tTJs precedes tricellulin recruitment

To clarify how tricellulin is recruited to the newly formed tTJs, we examined another tTJ component, angulin. Angulin family proteins are responsible for recruitment of tricellulin to tTJs in cultured epithelial cells [9, 10]. The angulin family is composed of three members, angulin-1/LSR, angulin-2/ILDR1 and angulin-3/ILDR2, and each can recruit tricellulin to tTJs. We identified the Xenopus gene for each angulin family member (Figures S4A and S4B). Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis revealed that angulin-1 is abundantly expressed in gastrula-stage embryos, while the angulin-2 expression level was less than one tenth of angulin-1, and angulin-3 was not detected (Figures S4C and S4D). Thus, we analyzed angulin-1 in this study. Immunofluorescence staining revealed that angulin-1 is expressed and localizes to tTJs in gastrula-stage embryos (Figure 6A). In live imaging experiments, angulin-1-3xGFP was recruited to newly formed tTJs in a similar manner to tricellulin, with angulin-1 puncta forming on either side of the new interface formed between neighbor cells following cytokinesis (Figures 6B and 6C; Movie S7). Angulin-1 recruitment precedes that of tricellulin for both the first and second tTJ (Figures 6D-6F and S5; Movie S7). We conclude that angulin-1 is recruited to newly formed cell vertices first, followed by tricellulin, suggesting that angulin-1 recruits tricellulin to tTJs following cytokinesis.

Figure 6. Angulin-1/LSR recruitment to the new tTJs precedes tricellulin recruitment.

A. Immunofluorescence staining of an embryo using anti-angulin-1 (green) and anti-ZO-1 (red). Scale bar, 20 μm.

B. Live imaging of an embryo expressing angulin-1-3xGFP (green) and mRFP-ZO-1 (red). Scale bar, 20 μm.

C. Live imaging of a dividing cell expressing angulin-1-3xGFP (green) and mRFP-ZO-1 (TJs, red). Note that two punctate angulin-1-3xGFP spots appear at the cell vertices of the new interface between neighbor cells (white arrows). Asterisks and “n”s indicate daughter cells and neighbor cells, respectively. Scale bar, 20 μm (left panels), 5 μm (right panels).

D. Live imaging of a dividing cell expressing angulin-3xGFP (green), mCherry-tricellulin (red) and mem-TagBFP (membrane, blue). Note that angulin-3xGFP puncta formation precedes that of mCherry-tricellulin (white arrows). Asterisks and “n”s indicate daughter cells and neighbor cells, respectively. Scale bar, 20 μm (left panels), 5 μm (right panels).

E. Kymograph of the formation of the two tTJs shown in D (yellow rectangle in D). Note that angulin-1 (green) appears earlier than the tricellulin (red).

F. Timing of recruitment of angulin-1 and tricellulin to the two nascent tTJs. Time points when the fluorescence intensity of angulin-1-3xGFP (green) or mCherry-tricellulin (red) reached half max (see Figure S5) are plotted. Half max intensity point of angulin-1-3xGFP at first tTJ is defined as t=0. Closed and open circles indicate average time points ± s.d. of angulin-1 (green) and tricellulin (red) recruitment at 1st and 2nd tTJs, respectively. Horizontal gray lines indicate time span from angulin-1 recruitment (green x) to tricellulin recruitment (red x) for 1st and 2nd tricellular junctions for individual cells. Note that tricellulin recruitment is later than angulin-1 for both tTJs. Error bars, S.E.M. Statistics, two-tailed paired Student’s t-test, p=0.013 (1st tTJ) and 0.016 (2nd tTJ).

See also Figures S4 and S5, and Movie S7.

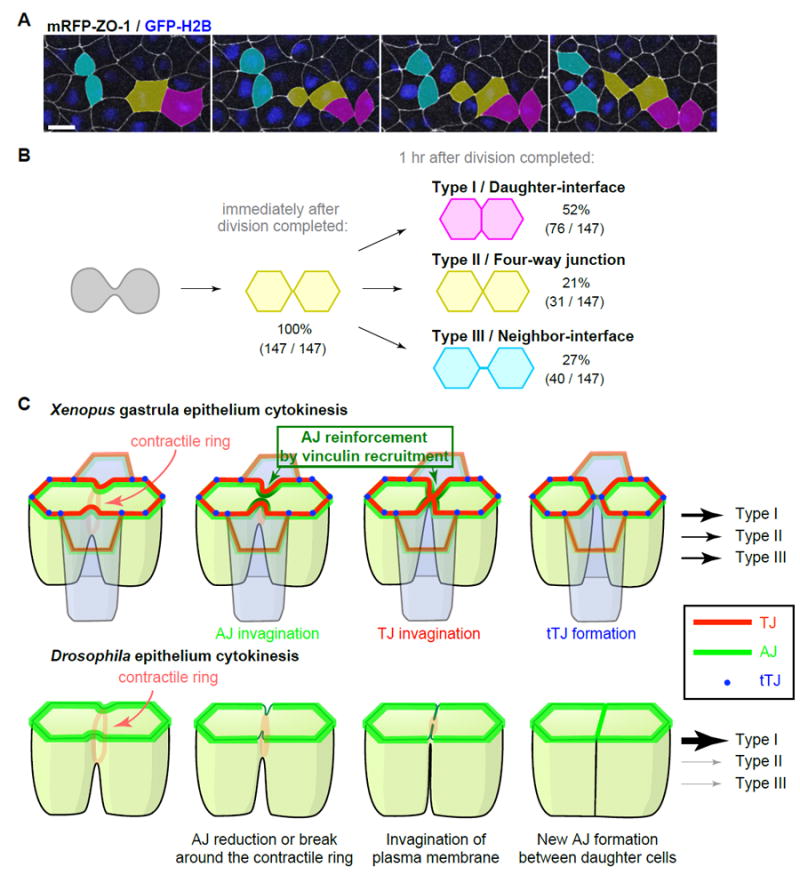

Cell packing geometry after Xenopus epithelial cytokinesis

In the Xenopus gastrula epithelium, both AJs and TJs are maintained and invaginate with the ingressing contractile ring, and consequently, a new interface forms between cells formerly neighboring the cleavage plane (neighbor cells) immediately following cytokinesis (Figures S3, 5 and 6). In contrast, in Drosophila, AJs exhibit a reduction in E-cadherin at the point where the contractile ring connects to the AJ and become disengaged from the contractile ring, and the new interface forms between daughter cells [31, 52, 53]. This difference in cell geometry following cytokinesis prompted us to analyze whether the new interface between neighbor cells in Xenopus gastrula epithelium is maintained or reorganized over time. To examine this question, we conducted long-term live imaging using mRFP-ZO-1-expressing embryos (Figure 7A; Movie S8). Immediately after cell division, 100% of cells formed a short new interface between neighbor cells (Figure 7B). One hour after cytokinesis completed, we observed three types of cell packing patterns: type I/daughter interface, type II/four-way junction, and type III/neighbor interface (Figure 7B; naming convention according to Gibson and colleagues [24]). Half of new junctions had reorganized to daughter interfaces (type I, 52%), and the other half still made interfaces between neighbor cells (type II plus type III, 48%). We examined the behavior of tricellulin for cells that had reorganized to a type I/daughter interface and found that the two tTJs initially formed at the vertices of the short neighbor interface but reorganized over time to become the two tTJs of a daughter interface (Figure S6A, Movie S8). These data provide new information about how cytokinesis contributes to the cell packing pattern observed in developing vertebrate epithelia.

Figure 7. Three types of packing patterns for daughter and neighboring cells after vertebrate epithelial cytokinesis.

A. Long-term live imaging of cell packing patterns after cytokinesis in embryos expressing mRFP-ZO-1 (pseudocolored white, TJs) and GFP-H2B (pseudocolored blue, chromosomes). Projected multi-plane en face images are shown. Scale bar, 20 μm.

B. Scheme of the three types of cell packing patterns observed after cell division. Each color (magenta for Type I, yellow for Type II and cyan for Type III) corresponds to the color shown in A.

C. Model of epithelial cell cytokinesis in Xenopus (vertebrate) and Drosophila (invertebrate). See also Figure S6 and Movie S8.

Discussion

Cell-cell junctions are crucial for maintaining tissue integrity and barrier function. Cell division presents a striking example of epithelial remodeling, where the dividing cell must form a new cell-cell junction after cytokinesis as well as maintain and remodel existing junctions during the major shape changes associated with cytokinesis. TJs and AJs must be stable enough to promote barrier function and tissue integrity during epithelial homeostasis but plastic enough to remodel when necessary. It has been unclear how this balance is achieved during cell division. This study provides novel insights into how epithelial integrity and barrier function are maintained during cytokinesis in vertebrate epithelial tissues (Figure 7C). Our results indicate that elevated tension from the contractile ring reinforces the AJs connected to the contractile ring by increasing the stability of individual AJ proteins and recruiting vinculin to the cleavage furrow. Furthermore, our results show for the first time the process of de novo tTJ formation following cytokinesis; angulin-1 then tricellulin are recruited to the two nascent tTJs that flank the midbody. The data presented here also highlight important differences in how cell-cell junctions are remodeled during epithelial cell division in Xenopus vs. Drosophila.

Comparison of epithelial cytokinesis in vertebrates and invertebrates

Recently, three labs described AJ behaviors during cytokinesis in Drosophila epithelia using live imaging [31, 52, 53]. Notably, the structure and molecular composition of cell-cell junctions is distinct between vertebrates and invertebrates [3, 4, 54]. Vertebrates, including Xenopus, have TJs and AJs, whereas invertebrates, including Drosophila, have AJs and septate junctions [54, 55], which serve an analogous function to TJs while differing in ultrastructure. Likewise, the ultrastructure of tricellular junctions is distinct between vertebrates and Drosophila [56].

We identified a number of striking differences in Xenopus epithelial cytokinesis compared with Drosophila. First, AJs and TJs are maintained throughout cytokinesis and are persistently connected to the contractile ring. In fact, we observed a slight increase in fluorescence intensity of ZO-1 and E-cadherin at the cleavage furrow early in cytokinesis and increased recruitment of vinculin at the furrow throughout cytokinesis. These observations are in clear contrast to the behaviors of AJs in the Drosophila embryonic epidermal epithelium [31] or the dorsal thorax pupal epithelium [52, 53] (Figure 7C). In Drosophila epithelial cytokinesis, the AJ exhibits a break or reduction in E-cadherin at the point where the contractile ring connects to the AJ and then becomes disengaged from the contractile ring. In fact, in the embryonic epithelium, a gap appears between the dividing cell and its neighbors [31]. Inhibition of endogenous vinculin recruitment to AJs at the cleavage furrow by expressing dominant negative vinculin resulted in the reduction of both AJ and TJ proteins at the cleavage furrow, mimicing the reduction of AJs observed in Drosophila epithelial cytokinesis. The differences observed between the systems may arise from a unique AJ reinforcement mechanism present in the vertebrate epithelium. Notably, the Drosophila vinculin gene is dispensable [57], whereas vinculin knockout mice have severe defects in heart and brain development leading to embryonic lethality [58]. It is possible that the AJ-reinforcing function of vinculin may only be important in vertebrates, although further studies are required to directly test the function of vinculin at AJs in Drosophila.

Epithelial cell packing geometry

Both the orientation of cell division and the geometry of the resulting daughter cells are important determinants for cell packing patterns and for shaping epithelial tissues [24, 59-61] Our studies revealed a difference in cell geometry following cytokinesis between Xenopus and Drosophila epithelia. After completion of cytokinesis in Xenopus epithelia, new junctions initially form between neighbor cells; subsequently, about half of these remodel to daughter interfaces over time. In contrast, in Drosophila, new AJs form almost exclusively between daughter cells [24, 31, 52, 53, 59, 62]. This difference could be due to a number of factors including the distinct structure and molecular components of the junctions, differences in cortical or junctional tension, or differing requirements for barrier function. Previous studies in vertebrates have demonstrated that cells neighboring the cleavage furrow can intercalate between the recently divided cells [27, 63]. This is consistent with our observations that cells initially form a short interface between neighbors, and even one hour after cytokinesis, many daughter cells are still separated by neighbor cells. Interestingly, it was recently reported in chick embryos that cell geometry after cytokinesis changes over the course of development, and cell division-mediated epithelial cell rearrangements are important for proper gastrulation movements [64]. We propose that the observed differences in cell geometry and adhesive contacts following cell division could have implications on how epithelial tissue growth proceeds in Xenopus vs. Drosophila. This will be an interesting question to pursue in future experimental and mathematical modeling studies.

Mechanics of cytokinesis

Cytokinesis is driven by the assembly and constriction of an actomyosin contractile ring. We investigated the impact of mechanical force generated by the contractile ring on junction protein dynamics. Our FRAP data indicate that the AJs at the cleavage furrow respond to increased tension generated by the contractile ring by locally stabilizing E-cadherin and β-catenin. Furthermore, perturbation of vinculin-dependent AJ reinforcement by expressing dominant negative vinculin significantly increased the ingression rate of contractile rings. This suggests that cells neighboring the cleavage furrow provide counteracting tension to the force generated by the contractile ring, which is transmitted through the reinforced AJs at the cleavage furrow. Therefore, local strengthening of the AJ may be important for maintaining an adhesive connection as the neighbor cells are pulled in by the ingressing contractile ring.

Nascent tTJ formation following cytokinesis

tTJs are important for the maintenance of barrier function [11] and were recently implicated in determining of spindle orientation in the Drosophila epithelium [65]. In this study, we observed tTJ biogenesis following cytokinesis for the first time using angulin-1 and tricellulin as probes. Angulin-1 accumulated first, forming two foci located on either side of the midbody, and tricellulin accumulated after angulin-1 at each of the foci. These results suggest that angulin-1 initiates tTJ formation at the end of cytokinesis. This timing of recruitment is consistent with previous observations in cultured cell lines, indicating that angulin family proteins are responsible for tricellulin recruitment to tTJs [9, 10]. However, it remains unknown how the angulin proteins recognize and accumulate at the points where new tTJs should be established. It is also intriguing that one tTJ forms before the other.

Taken together, our data provide novel insights into how epithelial integrity and barrier function are maintained throughout cytokinesis in a vertebrate epithelial tissue. Our results highlight important differences in how cell-cell junctions are remodeled during cell division in the vertebrate Xenopus vs. Drosophila, and they reveal for the first time how new tTJs are born following cytokinesis. This work also raises multiple questions for future studies. For example, it will be important to examine whether the Xenopus-type division described here is common in other vertebrate epithelial tissues, both developing and adult tissues. Specifically, it will be interesting to test epithelial tissues that represent different physical cellular properties such as junctional tension to determine whether junctions are maintained or disengaged at the furrow, the impact of contractile ring mechanics on individual junction protein dynamics, and the effect on cytokinesis success. Finally, how tTJs are reorganized during cell shape changes or morphogenetic movements and how the angulin proteins recognize and accumulate at the points where new tTJs should be established are fascinating questions.

Experimental procedures

Xenopus embryos and microinjection

All studies conducted using Xenopus embryos strictly adhere to the compliance standards of the US Department of Health and Human Services Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the University of Michigan’s IACUC. Xenopus embryos were collected, in vitro fertilized, de-jellied and microinjected with mRNAs for fluorescent probes using methods described previously [49, 66]. Embryos were injected at either the 2-cell or the 4-cell stage and allowed to develop to gastrula-stage (Nieuwkoop and Faber stage 10-11).

Barrier assay

Gastrula-stage embryos expressing mRFP-ZO-1 and/or mCherry-H2B were mounted in 10 μM fluorescein (332 Da) and observed. As positive control of barrier failure, embryos were injected with 5 nl of 100 mM EGTA in 0.1x MMR into the blastocoel and observed after 30 min.

Immunostaining

Gastrula-stage albino embryos were immunostained by methods described previously [49, 66] with the following changes: embryos were fixed with 2% TCA (for staining of β-catenin and ZO-1) or 2% formaldehyde (for staining of tricellulin, angulin-1 and ZO-1) in 1x phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 2 h, permeabilized with 2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 20 min, and blocked in Tris-buffered saline (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (10082-139; Invitrogen) for 1-2 h at room temperature. See Supplemental Experimental Procedures for primary and secondary antibodies. Embryos were incubated with 10 μg/ml 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (D1306; Life Technologies) and mounted in Vectashield mounting medium (H-1000; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA).

Live and fixed confocal microscopy

Fluorescent confocal images were collected on an inverted Olympus Fluoview 1000 microscope equipped with a 60X supercorrected PLAPON 60XOSC objective (NA = 1.4, working distance = 0.12 mm) and FV10-ASW software. Live and fixed imaging was carried out as described previously [49, 66].

Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching

FRAP was performed on gastrula-stage albino embryos using the microscope described above. A 405 nm laser was pulsed in a circular ROI (35% laser power, 600 ms, diameter of 7.8 μm) to bleach junction proteins of interphase cells or the cleavage furrow or polar region of dividing cells. In dividing cells, bleaching was performed once the cleavage furrow was apparent, at ~10-25% ingression. The apical surface (3 μm deep) of the embryos was imaged for all experiments. This allowed the tracking of the apical region of the cleavage furrow in the Z direction during cytokinesis.

Statistical analysis

A two-tailed paired t-test was used for statistical analysis unless otherwise specified. Statistical analysis of FRAP data was performed in GraphPad Prism version 6 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla California USA). E-cadherin data was fit with a double exponential curve to derive the fast and slow t1/2 and the plateau/mobile fraction. A single exponential curve was fit to data for β-catenin, claudin-6, and ZO-1 to derive the t1/2 and the plateau/mobile fraction. Curves were constrained to y=0 and the plateau to be less than 1. An unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction was used for statistical analysis, and data equal to or greater than 1.1 or less than or equal to -0.1 were removed from statistical analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Itoh for the mouse anti-ZO-1 antibody; W.M. Bement for pCS2+/Lifeact-GFP; J.B. Wallingford for pCS2+/mem-TagBFP; P.D. McCrea for pCS2+/xE-cadherin-3HA; E.M. De Robertis for pCS2+/claudin-6 (XCla)-HA; C. Broussard and M. Hemmeter for developing software to streamline FRAP analysis; M.L. Fekete for excellent technical support; and M. Furuse, D. Antonetti, Y. Yamashita, and members of our lab for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH Grants (R00 GM089765 and R01 GM112794) to A.L.M., a Postdoctoral Fellowship from the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science to T.H., NSF Graduate Research Fellowships to T.R.A. and R.E.S., and a Beckman Scholars Fellowship to K.M.D.

Footnotes

Author contributions

Conceptualization, T.H. and A.L.M.; Methodology, T.H. and A.L.M., Investigation, T.H., T.R.A., and K.M.D.; Writing – Original Draft, T.H. and A.L.M.; Writing – Reviewing ’ Editing, T.H., T.R.A., R.E.S. and A.L.M.; Funding Acquisition, A.L.M.; Resources, T.H., T.R.A. and R.E.S.; Supervision, A.L.M.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Eisenhoffer GT, Rosenblatt J. Bringing balance by force: live cell extrusion controls epithelial cell numbers. Trends Cell Biol. 2013;23:185–192. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guillot C, Lecuit T. Mechanics of epithelial tissue homeostasis and morphogenesis. Science. 2013;340:1185–1189. doi: 10.1126/science.1235249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hartsock A, Nelson WJ. Adherens and tight junctions: structure, function and connections to the actin cytoskeleton. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:660–669. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Itallie CM, Anderson JM. Architecture of tight junctions and principles of molecular composition. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2014;36:157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Green KJ, Getsios S, Troyanovsky S, Godsel LM. Intercellular junction assembly, dynamics, and homeostasis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a000125. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodgers LS, Fanning AS. Regulation of epithelial permeability by the actin cytoskeleton. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2011;68:653–660. doi: 10.1002/cm.20547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Furuse M, Sasaki H, Fujimoto K, Tsukita S. A single gene product, claudin-1 or -2, reconstitutes tight junction strands and recruits occludin in fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:391–401. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.2.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Itoh M, Morita K, Tsukita S. Characterization of ZO-2 as a MAGUK family member associated with tight as well as adherens junctions with a binding affinity to occludin and alpha catenin. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:5981–5986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.9.5981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higashi T, Tokuda S, Kitajiri S, Masuda S, Nakamura H, Oda Y, Furuse M. Analysis of the 'angulin' proteins LSR, ILDR1 and ILDR2--tricellulin recruitment, epithelial barrier function and implication in deafness pathogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:966–977. doi: 10.1242/jcs.116442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Masuda S, Oda Y, Sasaki H, Ikenouchi J, Higashi T, Akashi M, Nishi E, Furuse M. LSR defines cell corners for tricellular tight junction formation in epithelial cells. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:548–555. doi: 10.1242/jcs.072058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ikenouchi J, Furuse M, Furuse K, Sasaki H, Tsukita S. Tricellulin constitutes a novel barrier at tricellular contacts of epithelial cells. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:939–945. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200510043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lecuit T, Yap AS. E-cadherin junctions as active mechanical integrators in tissue dynamics. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:533–539. doi: 10.1038/ncb3136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yonemura S, Wada Y, Watanabe T, Nagafuchi A, Shibata M. alpha-Catenin as a tension transducer that induces adherens junction development. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:533–542. doi: 10.1038/ncb2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huveneers S, Oldenburg J, Spanjaard E, van der Krogt G, Grigoriev I, Akhmanova A, Rehmann H, de Rooij J. Vinculin associates with endothelial VE-cadherin junctions to control force-dependent remodeling. J Cell Biol. 2012;196:641–652. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201108120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buckley CD, Tan J, Anderson KL, Hanein D, Volkmann N, Weis WI, Nelson WJ, Dunn AR. Cell adhesion. The minimal cadherin-catenin complex binds to actin filaments under force. Science. 2014;346:1254211. doi: 10.1126/science.1254211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leerberg JM, Gomez GA, Verma S, Moussa EJ, Wu SK, Priya R, Hoffman BD, Grashoff C, Schwartz MA, Yap AS. Tension-sensitive actin assembly supports contractility at the epithelial zonula adherens. Curr Biol. 2014;24:1689–1699. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nowotarski SH, Peifer M. Cell biology: a tense but good day for actin at cell-cell junctions. Curr Biol. 2014;24:R688–690. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi W, Acharya BR, Peyret G, Fardin MA, Mege RM, Ladoux B, Yap AS, Fanning AS, Peifer M. Remodeling the zonula adherens in response to tension and the role of afadin in this response. J Cell Biol. 2016;213:243–260. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201506115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ratheesh A, Yap AS. A bigger picture: classical cadherins and the dynamic actin cytoskeleton. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:673–679. doi: 10.1038/nrm3431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen L, Weber CR, Turner JR. The tight junction protein complex undergoes rapid and continuous molecular remodeling at steady state. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:683–695. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200711165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang J, Huang L, Chen YJ, Austin E, Devor CE, Roegiers F, Hong Y. Differential regulation of adherens junction dynamics during apical-basal polarization. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:4001–4013. doi: 10.1242/jcs.086694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamada S, Pokutta S, Drees F, Weis WI, Nelson WJ. Deconstructing the cadherin-catenin-actin complex. Cell. 2005;123:889–901. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu D, Marchiando AM, Weber CR, Raleigh DR, Wang Y, Shen L, Turner JR. MLCK-dependent exchange and actin binding region-dependent anchoring of ZO-1 regulate tight junction barrier function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:8237–8241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908869107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gibson MC, Patel AB, Nagpal R, Perrimon N. The emergence of geometric order in proliferating metazoan epithelia. Nature. 2006;442:1038–1041. doi: 10.1038/nature05014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fededa JP, Gerlich DW. Molecular control of animal cell cytokinesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:440–447. doi: 10.1038/ncb2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Green RA, Paluch E, Oegema K. Cytokinesis in animal cells. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2012;28:29–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101011-155718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jinguji Y, Ishikawa H. Electron microscopic observations on the maintenance of the tight junction during cell division in the epithelium of the mouse small intestine. Cell Struct Funct. 1992;17:27–37. doi: 10.1247/csf.17.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baker J, Garrod D. Epithelial cells retain junctions during mitosis. J Cell Sci. 1993;104(Pt 2):415–425. doi: 10.1242/jcs.104.2.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takeichi M. Morphogenetic roles of classic cadherins. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1995;7:619–627. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu KC, Cheney RE. Myosins in cell junctions. Bioarchitecture. 2012;2 doi: 10.4161/bioa.21791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guillot C, Lecuit T. Adhesion disengagement uncouples intrinsic and extrinsic forces to drive cytokinesis in epithelial tissues. Dev Cell. 2013;24:227–241. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Le Page Y, Chartrain I, Badouel C, Tassan JP. A functional analysis of MELK in cell division reveals a transition in the mode of cytokinesis during Xenopus development. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:958–968. doi: 10.1242/jcs.069567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reinsch S, Karsenti E. Orientation of spindle axis and distribution of plasma membrane proteins during cell division in polarized MDCKII cells. J Cell Biol. 1994;126:1509–1526. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.6.1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Priya R, Yap AS, Gomez GA. E-cadherin supports steady-state Rho signaling at the epithelial zonula adherens. Differentiation. 2013;86:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ratheesh A, Gomez GA, Priya R, Verma S, Kovacs EM, Jiang K, Brown NH, Akhmanova A, Stehbens SJ, Yap AS. Centralspindlin and alpha-catenin regulate Rho signalling at the epithelial zonula adherens. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:818–828. doi: 10.1038/ncb2532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fernandez-Gonzalez R, Simoes Sde M, Roper JC, Eaton S, Zallen JA. Myosin II dynamics are regulated by tension in intercalating cells. Dev Cell. 2009;17:736–743. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ishihara H, Martin BL, Brautigan DL, Karaki H, Ozaki H, Kato Y, Fusetani N, Watabe S, Hashimoto K, Uemura D, et al. Calyculin A and okadaic acid: inhibitors of protein phosphatase activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;159:871–877. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)92189-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Narumiya S, Ishizaki T, Uehata M. Use and properties of ROCK-specific inhibitor Y-27632. Methods Enzymol. 2000;325:273–284. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)25449-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Joshi SD, von Dassow M, Davidson LA. Experimental control of excitable embryonic tissues: three stimuli induce rapid epithelial contraction. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:103–114. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim Y, Hazar M, Vijayraghavan DS, Song J, Jackson TR, Joshi SD, Messner WC, Davidson LA, LeDuc PR. Mechanochemical actuators of embryonic epithelial contractility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:14366–14371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1405209111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choi HJ, Pokutta S, Cadwell GW, Bobkov AA, Bankston LA, Liddington RC, Weis WI. alphaE-catenin is an autoinhibited molecule that coactivates vinculin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:8576–8581. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203906109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peng X, Maiers JL, Choudhury D, Craig SW, DeMali KA. alpha-Catenin uses a novel mechanism to activate vinculin. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:7728–7737. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.297481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Friend DS, Gilula NB. Variations in tight and gap junctions in mammalian tissues. J Cell Biol. 1972;53:758–776. doi: 10.1083/jcb.53.3.758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Staehelin LA. Further observations on the fine structure of freeze-cleaved tight junctions. J Cell Sci. 1973;13:763–786. doi: 10.1242/jcs.13.3.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Staehelin LA, Mukherjee TM, Williams AW. Freeze-etch appearance of the tight junctions in the epithelium of small and large intestine of mice. Protoplasma. 1969;67:165–184. doi: 10.1007/BF01248737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wade JB, Karnovsky MJ. The structure of the zonula occludens. A single fibril model based on freeze-fracture. J Cell Biol. 1974;60:168–180. doi: 10.1083/jcb.60.1.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walker DC, MacKenzie A, Hulbert WC, Hogg JC. A re-assessment of the tricellular region of epithelial cell tight junctions in trachea of guinea pig. Acta Anat (Basel) 1985;122:35–38. doi: 10.1159/000145982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sohet F, Lin C, Munji RN, Lee SY, Ruderisch N, Soung A, Arnold TD, Derugin N, Vexler ZS, Yen FT, et al. LSR/angulin-1 is a tricellular tight junction protein involved in blood-brain barrier formation. J Cell Biol. 2015;208:703–711. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201410131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Breznau EB, Semack AC, Higashi T, Miller AL. MgcRacGAP restricts active RhoA at the cytokinetic furrow and both RhoA and Rac1 at cell-cell junctions in epithelial cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2015;26:2439–2455. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E14-11-1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miller AL, Bement WM. Regulation of cytokinesis by Rho GTPase flux. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:71–77. doi: 10.1038/ncb1814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morais-de-Sa E, Sunkel C. Adherens junctions determine the apical position of the midbody during follicular epithelial cell division. EMBO Rep. 2013;14:696–703. doi: 10.1038/embor.2013.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Founounou N, Loyer N, Le Borgne R. Septins regulate the contractility of the actomyosin ring to enable adherens junction remodeling during cytokinesis of epithelial cells. Dev Cell. 2013;24:242–255. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Herszterg S, Leibfried A, Bosveld F, Martin C, Bellaiche Y. Interplay between the dividing cell and its neighbors regulates adherens junction formation during cytokinesis in epithelial tissue. Dev Cell. 2013;24:256–270. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tepass U, Tanentzapf G, Ward R, Fehon R. Epithelial cell polarity and cell junctions in Drosophila. Annu Rev Genet. 2001;35:747–784. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.35.102401.091415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Furuse M, Tsukita S. Claudins in occluding junctions of humans and flies. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Byri S, Misra T, Syed ZA, Batz T, Shah J, Boril L, Glashauser J, Aegerter-Wilmsen T, Matzat T, Moussian B, et al. The Triple-Repeat Protein Anakonda Controls Epithelial Tricellular Junction Formation in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2015;33:535–548. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alatortsev VE, Kramerova IA, Frolov MV, Lavrov SA, Westphal ED. Vinculin gene is non-essential in Drosophila melanogaster. FEBS Lett. 1997;413:197–201. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00901-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu W, Baribault H, Adamson ED. Vinculin knockout results in heart and brain defects during embryonic development. Development. 1998;125:327–337. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.2.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Baena-Lopez LA, Baonza A, Garcia-Bellido A. The orientation of cell divisions determines the shape of Drosophila organs. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1640–1644. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lechler T, Fuchs E. Asymmetric cell divisions promote stratification and differentiation of mammalian skin. Nature. 2005;437:275–280. doi: 10.1038/nature03922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Farhadifar R, Roper JC, Aigouy B, Eaton S, Julicher F. The influence of cell mechanics, cell-cell interactions, and proliferation on epithelial packing. Curr Biol. 2007;17:2095–2104. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aigouy B, Farhadifar R, Staple DB, Sagner A, Roper JC, Julicher F, Eaton S. Cell flow reorients the axis of planar polarity in the wing epithelium of Drosophila. Cell. 2010;142:773–786. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hatte G, Tramier M, Prigent C, Tassan JP. Epithelial cell division in the Xenopus laevis embryo during gastrulation. Int J Dev Biol. 2014;58:775–781. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.140277jt. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Firmino J, Rocancourt D, Saadaoui M, Moreau C, Gros J. Cell Division Drives Epithelial Cell Rearrangements during Gastrulation in Chick. Dev Cell. 2016;36:249–261. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bosveld F, Markova O, Guirao B, Martin C, Wang Z, Pierre A, Balakireva M, Gaugue I, Ainslie A, Christophorou N, et al. Epithelial tricellular junctions act as interphase cell shape sensors to orient mitosis. Nature. 2016;530:495–498. doi: 10.1038/nature16970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Reyes CC, Jin M, Breznau EB, Espino R, Delgado-Gonzalo R, Goryachev AB, Miller AL. Anillin Regulates Cell-Cell Junction Integrity by Organizing Junctional Accumulation of Rho-GTP and Actomyosin. Curr Biol. 2014;24:1263–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.