Abstract

Background

The expansion of Zika virus (ZIKV) into the Western Hemisphere and recognition of congenital Zika syndrome have created a need for a safe, effective and rapidly-scalable ZIKV vaccine. We developed a purified formalin-inactivated ZIKV vaccine (ZPIV) candidate that was advanced to human testing after demonstrating protective efficacy in mice and non-human primates against viremia after ZIKV challenge.

Methods

We carried out three phase 1, placebo-controlled, double-blind trials of ZPIV co-formulated with aluminum hydroxide gel. Healthy adults were randomly assigned (4:1 or 5:1) to receive 5 μg of ZPIV or saline placebo, intramuscularly, at days 1 and 29. Investigators and participants were masked to group assignment (vaccine or placebo). The primary objective of all three trials was to assess the interim safety and immunogenicity of the ZPIV candidate. We measured the frequency of adverse events and ZIKV envelope microneutralization (MN) titers through day 57 to meet this objective. We also assessed the protective efficacy of purified immunoglobulin G (IgG) from vaccinees against Zika viremia in mice. The three trials are registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, numbers: NCT02963909, NCT02952833, NCT02937233).

Findings

Sixty-eight participants were enrolled across the three trials between November 7, 2016 and January 25, 2017. Due to enrollment error, one participant was excluded and sixty-seven participants (55 vaccine, 12 placebo) received the full series of two injections. The vaccine caused only mild or moderate reactogenicity. By day 57, 92% (N=51) of vaccine recipients seroconverted (MN titer > 1:10). Microneutralization geometric mean titers peaked at day 43 and exceeded protective thresholds observed in prior animal models. Adoptive transfer of day 57 purified IgG provided robust protection against viremia in ZIKV-challenged mice.

Interpretation

ZPIV was well-tolerated and elicited robust neutralizing antibody titers in healthy adults. ZPIV-elicited human antibodies protected against viral challenge in mice, potentially providing a quantifiable and prospectively testable correlate of immunity for this vaccine candidate.

Funding

US Department of Defense, Defense Health Agency and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases.

Keywords: Zika Virus, Inactivated Vaccines, Humoral Immunity, Phase I Clinical Trial

INTRODUCTION

The emergence of Zika virus (ZIKV) as a major cause of microcephaly and other neurologic defects1–6 echoes the devastating impact of other congenital infections7. The historical experience with the eradication of congenital rubella syndrome by aggressive vaccination campaigns holds promise that the same result could be achieved for ZIKV8. ZIKV infection is also associated with significant risks for infected adults9–12. Unknown duration of infectivity, continued viral transmission, mosquito vector expansion and vulnerability of immunologically naïve populations underscore the continued need for a safe and effective vaccine13,14, particularly as ZIKV becomes endemic globally and threatens to resurge to previous epidemic or unseen pandemic proportions13,14.

Prior experience with other flaviviruses and inactivated virus vaccine platforms has facilitated the accelerated development of ZPIV: a purified, formalin-inactivated ZIKV vaccine candidate. This vaccine candidate derives from a 2015 Puerto Rican ZIKV strain (PRVABC59; ZIKV-PR) that is closely related to the 2015 Brazilian strain (SPH2015; ZIKV-BR), which is circulating through much of Latin America15. Preclinical studies with ZPIV have demonstrated complete protection from viremia following wild-type challenge with ZIKV-PR or ZIKV-BR in immunocompetent mice16 and non-human primates17 (NHPs). Vaccination in both animal models has induced robust antibody responses, with particularly high titers among NHPs (50% microneutralization titer (MN50) of 3.66log) two weeks after completion of a two-dose, 5μg, 1/29-day regimen16,17. This dosage and schedule was selected on the basis of WRAIR’s experience with other inactivated flavivirus vaccines. Adoptive transfer of purified immunoglobulin G (IgG) from vaccinated mice and NHPs into the same but naïve animal models provided complete protection from ZIKV challenge at a threshold MN50 titer between one (1:10) and two (1:100) logarithms, similar to accepted correlates for Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), tick borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) and yellow fever virus (YFV) vaccines18. These data, thus, provide a mechanistic correlate of protective immunity and a basis on which to advance testing to human trials16,17.

We report the early safety and immunogenicity results of three phase 1, placebo-controlled, double-blind trials of ZPIV and demonstrate that it is both well-tolerated and immunogenic. We also show that purified antibody from vaccine recipients is protective in murine challenge studies, thus supporting ZIKV neutralizing IgG as a correlate of protection that is readily achievable with the currently tested vaccine regimen.

METHODS

Vaccine

The ZPIV candidate was developed, manufactured and provided to all sites by the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR). ZPIV is a chromatographic column purified, formalin-inactivated Zika virus (PRVABC59), initially obtained from the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC; Fort Collins, Colorado) and cultivated and passaged in a qualified Vero cell line. After purification and inactivation, ZPIV was diluted to 20 μg/mL and vialed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), adsorbed 1:1 to aluminum hydroxide gel (Alhydrogel®, 2 mg/mL). Each vial provided one 0.5 mL dose of 5 μg protein and 500 μg aluminum hydroxide adjuvant. Placebo formulations comprised PBS alone. Additional details on the manufacture of the study product are provided in the Supplementary Appendix.

Study Population and Study Design

The three studies included in this aggregate analysis are all phase 1, randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind trials occurring at single sites, and are each designed to address a unique question about background immunity, vaccine dosage, or vaccination schedule. The WRAIR trial is assessing the impact of pre-existing flavivirus immunity conferred by priming with either a licensed yellow fever (YF-VAX®) or Japanese encephalitis (IXIARO®) vaccine followed by ZPIV vaccination. The Saint Louis University (SLU) trial is evaluating safety and immunogenicity of three vaccine dosages (5 μg, 2.5 μg, 10 μg). The Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) trial is evaluating three dosing schedules: two doses separated by either four or two weeks, or a single dose. The first arms of all three trials were designed in harmony to enroll flavivirus-naïve adults who were vaccinated with 5 μg of Alhydrogel®-adjuvanted ZPIV at days 1 and 29. The trials were designed to evaluate the safety, reactogenicity and immunogenicity of ZPIV through the primary time point of day 57. Longer-term follow-up varies across trials, ranging from six to 18 months. Men and women, ages 18 to 49 years, were recruited if they had no history of flavivirus infection or vaccination or serologic evidence of such at the WRAIR and SLU sites (additional methods in Supplementary Appendix). Individuals with serologic evidence of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B or C infection were excluded from study participation. Additionally, pregnant or breast-feeding women were excluded. Significant medical conditions that, in the opinion of the investigator, precluded a participant from fulfilling study obligations were also used as a basis for exclusion. Site-specific institutional review boards approved protocols for each respective study. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before screening. The three trials are registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, numbers: NCT02963909, NCT02952833, NCT02937233).

Randomisation and masking

Participants were randomised at a ratio of vaccinated to controls of 5:1 at the SLU and BIDMC sites and 4:1 at WRAIR. Investigators and participants were masked to group assignment. Randomisation occurred independently but by uniform methods at the three study sites. In brief, a randomisation code list based on enrollment sequence was provided the statistician to the pharmacy at study initiation. With each new enrollment, an automated treatment number was generated that corresponded to the randomization code list. The unmasked pharmacy staff cross-referenced the treatment number against the original randomization list to identify the group to which that participant was assigned. Either active vaccine product or placebo was then pulled, labeled with only the study identification number and date and prepared for injection. The unmasked pharmacy and masked clinical staff had no communications regarding participant group assignment. Group assignment still remains masked to study clinicians as each of the three studies has not yet reached completion. Study clinical staff have remained blinded to individual-level results from the interim analysis; this is the primary reason why safety data remains aggregated and not stratified by treatment assignment.

Study Procedures

Participants were assessed on days 1, 2 (SLU), 4, 8, 15, 29, 32, 36, 43 (SLU, BIDMC) and 57. Solicited adverse events related to local injection site or systemic reactogenicity were collected through 7 days after each vaccination. Unsolicited adverse events were recorded for 28 days after each vaccination. We also sought safety data specifically on neurologic or neuroinflammatory adverse events of special interest (AESI). Information on AESI and serious adverse events (SAE) was collected throughout study follow-up with a memory aid for 7 days after each vaccination, reviewed by study investigators, and a questionnaire at each study visit that asked specifically about clinical manifestations reflective of newly developed neurologic or neuroinflammatory pathology. Blood was collected for safety at baseline prior to vaccination and one week after each vaccination to assess for changes in laboratory values. Immunologic parameters were measured at baseline (Day 1), just prior to priming vaccination, as well as one, two and four weeks after each vaccination, except in the WRAIR study which did not collect blood for immunogenicity at two weeks after the second vaccination (day 43). Safety laboratory evaluations performed at post-vaccination follow-up visits included a white blood cell count, hemoglobin, platelet count, serum creatinine, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, total bilirubin, blood urea nitrogen and creatinine. Additionally, a creatine phosphokinase and urine dipstick for protein and glucose were collected at BIDMC and SLU, respectively. Local and systemic adverse events were graded by the DMID Adult Toxicity Table (www.niaid.nih.gov/sites/default/files/dmidadulttox.pdf).

Antibody Response Measurements

A high-throughput ZIKV MN assay was developed for measuring ZIKV-specific neutralizing antibodies, based on a modified version of a qualified dengue virus (DENV) MN assay used in prior DENV vaccine clinical trials16. Seropositivity was defined as a titer ≥ 1:10. All MN assays were performed on the same platform within one laboratory at WRAIR. The exclusion of participants with baseline flavivirus immunity in the WRAIR study was based on the same MN assay platform. For screening purposes, however, the assay was modified to provide a qualitative, rather than quantitative, readout of seropositivity. Participants at SLU were serologically screened for ZIKV, DENV, YFV and West Nile virus (WNV) using the CDC MACS ELISA assay. Baseline serum from SLU and BIDMC were retrospectively screened on the WRAIR MN platform for the same panel of flaviviruses. Results from this assay were correlated with the ELISA output and participants’ travel and vaccination histories.

Statistical Analysis

Sample sizes for each of the three trials were determined separately. The WRAIR and SLU studies were respectively designed to have 80% power to observe at least one ZPIV-related adverse event if the true rate was 2.6% and 4.5%. The sample size of the BIDMC study was not based on formal hypothesis testing consideration but within the range of participants recommended in the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR 312.21). Statistical analyses were performed with SAS v9.4 (Cary, North Carolina). Summary and stratified (by study, treatment, day) MN assay data were reported as geometric mean titer (GMT) with 95% confidence interval (CI) and percent seroconverted. Exact binomial CIs were used for rates of seroconversion, as defined by both titers of ≥1:10 and ≥1:100. Titers below the lower limit of detection (LOD) of 1:10 were assigned a value of one half the lower LOD (1:5). Titers above the upper LOD (1:7290) were assigned a value of 1:7291. Solicited adverse events were summarized by the maximum severity experienced by each participant. Associations of demographic characteristics with peak and day 57 titers were assessed by Spearman correlation and linear regression methods. Two-sample t-tests were used to compare results between results across sites and paired t-tests for change between day 43 and day 57. Immunogenicity data were presented in aggregate and by treatment. Safety data were presented only in aggregate to balance the need to preserve study blinding procedures.

Adoptive Antibody Transfer

Polyclonal immunoglobulin G (IgG) was individually purified with protein G purification kits (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA) from day 43 plasma from each BIDMC participant (N=12) and one control. Total IgG was buffer-exchanged into 1× PBS according to methods previously described16. Purified IgG was infused intravenously into groups of naïve recipient Balb/c mice prior to ZIKV-BR challenge (102 plaque forming units (PFU)) at 2 hours after infusion. Groups of 5 mice received de-escalating doses (3 × 200 μl, 200 μl, 40 μl or 0 μl) of a 10 μg/ml solution of purified IgG. Protection from ZIKV infection was defined by assessment of viral load in mouse serum on days 1, 2, 3, 4 and 7 after challenge. Quantitative RT-PCR assay was used to measure viral load according to methods previously described16, 17.

Role of the funders

The funders were involved in the study design, study operations, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation as well as the write-up and editing of the report. The principal investigators at each site had access only to data for their respective sites (LL, SLG, KES). The ZPIV program leads (KM, NLM) and statisticians (JB, JT, AEK, PD) had access to all the data. The ZPIV program leads (KM, NLM) and the study sponsors had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

RESULTS

Study Participants

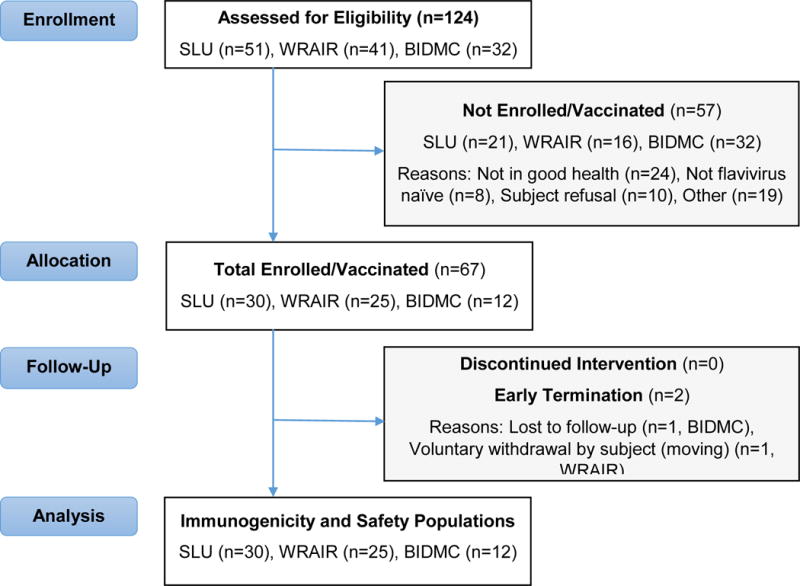

Between November 7, 2016 and January 25, 2017 a total of 68 participants were enrolled in the three trials. One participant was enrolled in error, thus only 67 individuals were vaccinated and followed. The mean age of all study participants was 31.5 years, with a slightly younger age distribution among those enrolled at BIDMC (table 1). There was generally an equal distribution of sex across all sites, but a variable racial make-up. Retrospective testing of baseline serum showed that seven of the 67 participants were found to have had serologic evidence of pre-existing flavivirus immunity. One participant was randomized in error but was not vaccinated. Of the 67 participants who were injected at days 1 and 29, 55 received ZPIV and 12 received a saline placebo. All participants received two vaccinations; however, a total of four participants (three at WRAIR, one at BIDMC) were lost to follow-up between the day 29 vaccination visit and the day 57 visit for primary interim immunologic endpoint analysis (figure 1).

Table 1.

Participant Baseline Characteristics

| SLU (N=30) |

WRAIR (N=25) |

BIDMC (N=12) |

All Groups (N=67) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Category | Characteristic | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Sex | Male | 15 | 50 | 14 | 56 | 6 | 50 | 35 | 52.2 |

| Female | 15 | 50 | 11 | 44 | 6 | 50 | 32 | 47.8 | |

| Ethnicity | Not Hispanic or Latino | 29 | 96.7 | 22 | 88 | 11 | 91.7 | 62 | 92.5 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 1 | 3.3 | 3 | 12 | 1 | 8.3 | 5 | 7.5 | |

| Race | American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 | – | 2 | 8 | 0 | – | 2 | 3.0 |

| Asian | 0 | – | 1 | 4 | 1 | 8.3 | 2 | 3.0 | |

| Black or African American | 2 | 6.7 | 10 | 40 | 1 | 8.3 | 13 | 19.4 | |

| White | 28 | 93.3 | 11 | 44 | 8 | 66.7 | 47 | 70.1 | |

| Multi-Racial | 0 | – | 1 | 4 | 2 | 16.7 | 3 | 4.5 | |

| Flavivirus Status* | Negative | 26 | 86.7 | 25 | 100 | 10 | 83.3 | 61 | 91.0 |

| Positive | 4 | 13.3 | 0 | – | 2 | 16.7 | 6 | 9.0 | |

| Age | Mean | 33.4 | 30.9 | 27.9 | 31.5 | ||||

| Standard Deviation | 9.5 | 8.8 | 6.5 | 8.9 | |||||

| Median | 32.5 | 29 | 29 | 29 | |||||

| Minimum | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | |||||

| Maximum | 49 | 49 | 38 | 49 | |||||

Baseline serum from all participants at Saint Louis University (SLU) and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) were retrospectively tested on the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR) microneutralization assay platform against a panel of 8 flaviviruses (dengue virus serotypes 1, 2, 3, 4; yellow fever virus; Japanese Encephalitis Virus; West Nile Virus; Zika virus).

Figure 1. CONSORT Flow Diagram.

The three study sites (WRAIR, SLU, BIDMC) enrolled concurrently and performed the studies independently. One participant at SLU was enrolled in error but was not randomized to receive vaccination. Sixty-seven participants received two injections. Three participants were either lost to follow up or did not complete the day 57 visit.

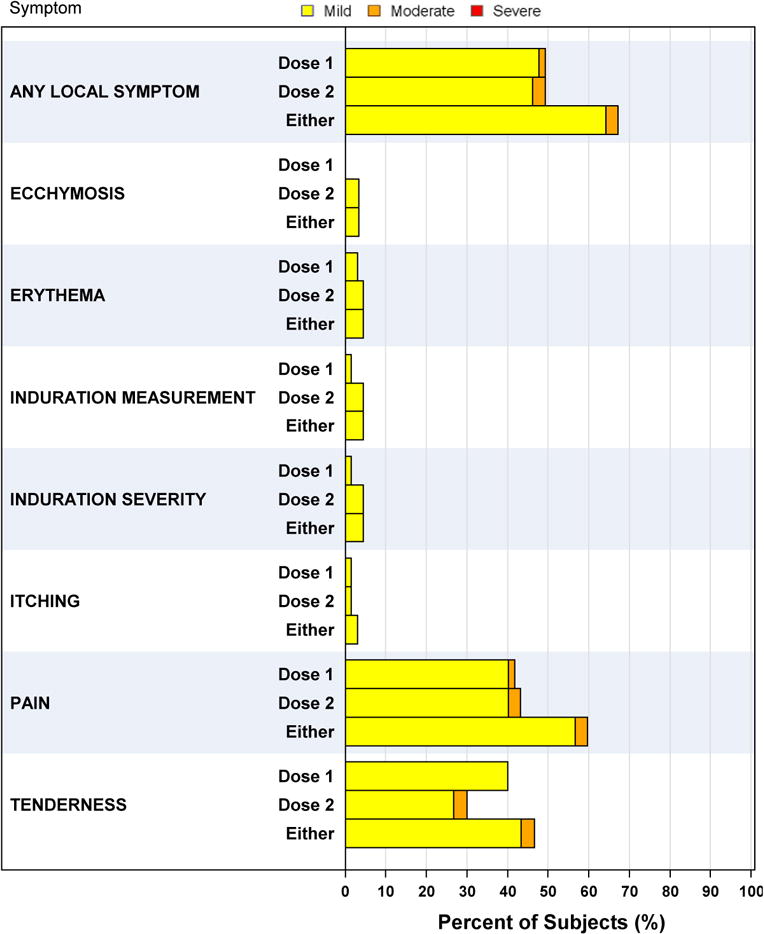

Safety

No participants suffered any AESI, related SAE or other significant adverse events that precipitated study withdrawal (figure 1, table S1 in the supplementary appendix). Safety data were obtained from all 67 participants. Overall, 84% (N=56) of participants reported one or more solicited symptoms following either the first or second dose. Approximately two thirds of participants (64% (N=43) mild and 3% (N=2) moderate) reported local reactogenicity (figure 2A). Systemic reactogenicity was equally common (49% (N=33) mild, 15% (N=10) moderate and 2% (N=1) severe) (figure 2B). The one individual with severe reactogenicity reported transient, self-limited vomiting that occurred and resolved quickly within days of vaccination and was not deemed attributable to vaccination but to an alternate cause. Injection site pain and tenderness were the most common local symptoms (60% (N=40) and 47% (N=32) of participants, respectively), while fatigue, headache and malaise were the most common systemic symptoms (43% (N=29), 39% (N=26) and 22% (N=15) of participants, respectively). Abnormalities in safety laboratory parameters were infrequent and mostly mild in severity.

Figure 2. Frequency of Solicited Adverse Events.

All adverse events were assessed for relatedness to the vaccine. All solicited events are reported. Adverse events were graded for severity on the basis of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Adult Toxicity Table (www.niaid.nih.gov/sites/default/files/dmidadulttox.pdf).

Immunogenicity

Neutralizing antibody titers against the ZIKV PRVABC59 strain were assessed from serum of 63 study participants through day 57. Overall, 92% (N=51) of vaccinated participants seroconverted by the time they reached day 57 (table 2), when defining seroconversion as a GMT of ≥1:10, which is the threshold of protection for other licensed flavivirus vaccines18. The proportion of seroconverters dropped to 77% (N=42) if the threshold was set at a titer of ≥1:100 (figure S1 and table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). Placebo participants across all three groups exhibited no rise in GMT at any of the visits. Four weeks after the first dose (day 29), and just prior to receiving the second dose, 11% (N=6) of participants had seroconverted (≥1:10). GMTs rose precipitously from day 29 to the first post-vaccination visit in all three groups (figure 3). At SLU and BIDMC, GMTs peaked at day 43—two weeks after the second dose—and then declined by day 57 (438 vs. 173, p<.001). No day 43 serum collection visit was scheduled at WRAIR.

Table 2.

Geometric Mean Antibody Titers

| 5 μg ZPIV | Placebo | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time Pointa | Statistic | SLU (N=25) |

WRAIR (N=20) |

BIDMC (N=10) |

All (N=55) |

All (N=12) |

| Day 1 | N* | 25 | 20 | 10 | 55 | 12 |

| GMT | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | |

| 95% CI | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Day 15 | N* | 25 | – | 10 | 35 | 7 |

| GMT | 5.0 | – | 8.6 | 5.8 | 5.0 | |

| 95% CI | – | – | 2.5, 28.8 | 4.3, 8.0 | – | |

| Day 29 | N* | 25 | 20 | 10 | 55 | 12 |

| GMT | 5.5 | 8.5 | 8.7 | 7.0 | 5.0 | |

| 95% CI | 4.5, 6.8 | 4.7, 15.3 | 2.5, 30.4 | 5.2, 9.5 | – | |

| Day 43 | N* | 25 | – | 10 | 35 | 7 |

| GMT | 316.9 | – | 983.3 | 437.9 | 5.0 | |

| 95% CI | 152.9, 656.6 | – | 425.4, 2272.5 | 245.7, 780.6 | – | |

| Day 57 | N* | 25 | 17 | 9 | 51 | 12 |

| GMT | 142.9 | 100.8 | 820.6 | 173.1 | 5.0 | |

| 95% CI | 70.3, 290.4 | 39.7, 255.7 | 357.1, 1885.8 | 104.6, 286.5 | – | |

| Peak Titer Post-dose 2 | N* | 25 | 17 | 10 | 52 | 12 |

| GMT | 345.6 | 100.8 | 1061.7 | 286.7 | 5.0 | |

| 95% CI | 166.4, 718.0 | 39.7, 255.7 | 452.8, 2489.2 | 170.6, 481.6 | – | |

Time points are relative to first dose of ZPIV/Placebo.

N=Number of subjects for whom data was available at any time point.

N*=Number of subjects for whom data are available at each time point.

Note: Blood is not drawn for MN assay at Day 15 and Day 43 for DMID Protocol 16-0062.

GMT = Geometric mean titer. 95% CI = 95% confidence interval of the GMT.

Overall, 92% (N=51) of vaccinated participants seroconverted (≥1:10) by day 57.

The seroconversion rate was 77% (N=42) at day 57 if the threshold titer was ≥1:100.

Figure 3. Zika Virus Neutralizing Antibody Responses.

Geometric mean neutralizing antibody titers at days 1, 15, 29, 43, 57 are shown by randomization (vaccine vs. placebo) and site. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals. Data points and error bars slightly offset from the study visit day on the x-axis for visual clarity.

The GMT among BIDMC participants exceeded baseline values earlier (day 14) and remained higher than the two other groups throughout the duration of follow-up (figure S2 in the supplementary appendix). At the predetermined primary immunologic endpoint of day 57, GMTs did not differ between SLU and WRAIR (143 vs. 101, p=0.54), but both were significantly lower than BIDMC (143 vs. 821 p<0.0001; 101 vs. 821 p<0.0001). As participants at BIDMC were younger than those at the other sites, a Spearman correlation analysis of age at enrollment as a continuous variable to the logarithm of the peak MN titer was carried out among active participants and showed a statistically significant negative correlation of −0.46 (p<0.0001) (figure S2 in the supplementary appendix).

Background Flavivirus Immunity

Given the differences in GMTs across the three sites, we interrogated the baseline serum samples of SLU and BIDMC participants for flavivirus seropositivity on the same MN platform used to screen participants at WRAIR. Overall, six participants who had screened negative for prior flavivirus exposure—either by history or ELISA—and received active vaccine product were found to have detectable flavivirus antibodies by MN assay (table S3 in the Supplementary Appendix). This was carried out as a post-hoc analysis. One of the participants with pre-existing flavivirus immunity received a placebo injection. Among those that received ZPIV, three at SLU and one at BIDMC screened positive for YFV. Additionally, one BIDMC study participant had antibodies to WNV and all four serotypes of DENV. None of the participants at WRAIR had pre-existing flavivirus sero-reactivity. ZIKV MN titers between flavivirus naïve and immune individuals did not differ at baseline but there was a statistically non-significant trend toward separation from day 15 and onward. Those with pre-existing flavivirus sero-reactivity had a trend toward higher titers at each follow up visit, particularly at day 43 and day 57; however, these differences did not reach statistical significance and are based on a small number of flavivirus sero-reactive participants.

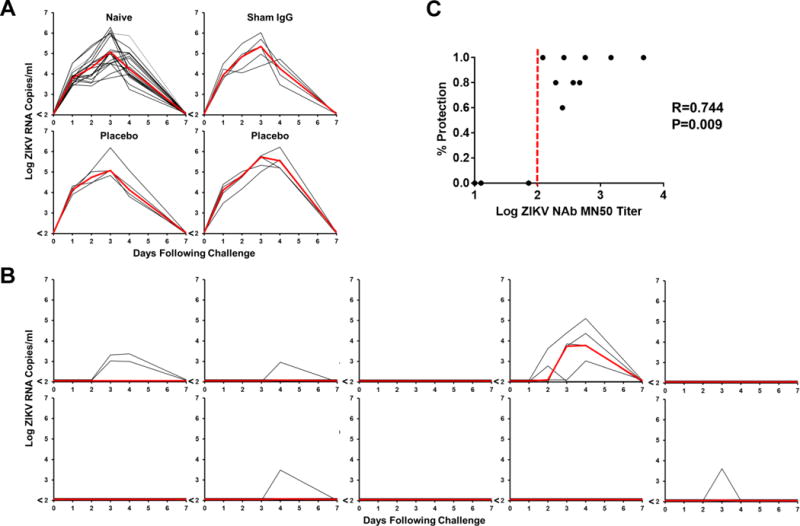

Passive Protection by Adoptive Antibody Transfer

We explored the a posteriori hypothesis that antibodies induced by ZPIV could confer protection from ZIKV challenge in a murine model, as was found previously in two preclinical studies16,17. As shown in figure 4, naïve mice challenged with the 2015 Brazilian strain (SPH2015) of ZIKV were viremic for approximately 7 days. Those that received adoptive transfer of purified IgG from a naïve individual or placebo recipients were not protected from challenge, as defined by the abrogation of viremia. In contrast, IgG from ZPIV vaccine recipients provided partial or complete protection from post-challenge viremia. Additionally, the MN50 titers of purified IgG preparations correlated with protective efficacy in murine adoptive transfer studies (Spearman r=0.744, p<0.0001).

Figure 4. Zika Virus Protection in Mice by Passive Human Antibody Transfer.

A. Viral loads (log RNA copies/ml) in naïve mice (N=20) and mice following transfer of purified IgG (N=5/group) from a naïve individual (sham), placebo recipients (placebo) and following challenge with 102 PFU ZIKV. B. Viral loads (log RNA copies/ml) in mice following transfer of purified IgG (N=5/group) from BIDMC ZPIV vaccine recipients that were challenged with 102 PFU ZIKV. C. Correlation of protective efficacy with MN50 titer post-antibody transfer and pre-virus challenge. Each dot represents one BIDMC participant.

DISCUSSION

We present the results of a Zika vaccine candidate tested in humans. A regimen of two intramuscular injections—separated by four weeks—of 5μg of ZPIV adjuvanted with aluminum hydroxide did not cause any significant safety concerns and elicited neutralizing antibody responses in nearly all individuals at two or four weeks after the last dose. The primary immunogenicity endpoint—GMT at day 57—reached a threshold titer (1:100) exceeding that which correlated with protection in both murine and NHP models16,17. In those earlier animal studies, adoptive transfer of vaccine-elicited antibodies at a MN50 titer of 1:60 protected both mice and NHPs from Zika viremia. Although GMTs waned moderately from day 43 to day 57 in the SLU and BIDMC groups, they remained above this 1:60 threshold titer. A durability study with ZPIV recently showed that NHPs had comparable MN50 titers that began declining 6 weeks after vaccine boost but maintained titers above 1:100 throughout follow up and were still protected from ZIKV challenge one year after initial vaccination (Abbink et al 2017 under review).

Pre-clinical studies of other Zika vaccine candidates currently in clinical trials have also defined specific threshold titers of neutralizing antibodies as surrogates of ZIKV protection19,20. One DNA vaccine candidate demonstrated 70% protection in NHPs at a neutralizing antibody titer of 1:1000 using a reporter virus particle assay19. Another purified inactivated virus vaccine candidate showed protection by passive antibody transfer in an immunodeficient mouse model at titers slightly higher than 1:100, as measured by a plaque reduction neutralization assay20. Additional ZIKV vaccine candidates, including another DNA and an mRNA vaccine candidate were both protective in murine models and elicited high titers of ZIKV neutralizing antibodies, but were not defined by a specific threshold of protection21–24. This latter DNA vaccine candidate preliminarily has been shown to be safe and immunogenic in humans25, though specific antibody titers that might correlate with protection were not defined.

Licensed vaccines for JEV, YFV and TBEV have historically been defined by specific threshold virus neutralization titers (1:10 in all cases) as surrogates of protection18. The precise antibody titers that afford protection from ZIKV in humans, however, cannot be directly inferred from preclinical studies with complete confidence, as several animal models with variable relevance have been used and assessed with different virus neutralization assay platforms that are of unknown comparability. Bridging studies across platforms on the same samples would enable more robust comparisons of immunologic potency and efficacy of different ZIKV vaccine candidates.

The role of other immunologic effector responses (i.e. cellular, innate) as a significant contributor to the mechanism by which this whole inactivated virus vaccine candidate provides protection is unclear, especially when compared to other candidates such as gene-based and live-attenuated vaccines. However, cellular responses may favorably influence the potency and durability of the antibody response. Additional investigation into additional effectors of immunity are, therefore, warranted in the analysis of the full dataset at study completion, particularly among different subsets of individuals, who may have altered immune responses, depending on age or baseline flavivirus serostatus. The final analysis from the three trials presented here will also better inform the optimal dose, schedule and population for vaccination. A fourth trial with ZPIV, not presented here, is underway in Puerto Rico and is intended to address the question of vaccine safety and immunogenicity in a cohort with a high prevalence of natural flavivirus immunity. This is of particular relevance given that participants enrolled into the current analysis, who were misclassified as flavivirus-naïve at baseline, may have benefited from boosting effect with respect to their humoral response to ZPIV. Additionally, the Puerto Rico and WRAIR trials are designed to address the concerns about antibody dependent enhancement of disease among individuals primed with previous flavivirus immunity.

The aggregate interim results from these three trials demonstrate that ZPIV has a tolerable safety profile and sufficient immunogenicity to provide potential clinical benefit. The current phase 1 trials are being modified to evaluate if a second boost (third dose) or higher dosage will yield more potent and sustained immunogenicity. The absence of a known correlate of risk or protection in a fetus necessitates additional efforts to bridge animal experiments with human studies. These initial interim human safety and immunogenicity results support the evaluation of the ZPIV candidate in larger, advanced phase clinical trials to establish an expanded safety dataset, evaluate durability and determine efficacy against natural ZIKV exposure.

Panel: Research in Context

Systematic review

The Zika virus outbreak has had a devastating impact on children and families across the Western Hemisphere since 2015. Although no longer declared a public health emergency of international concern, cases of Zika virus infection are still occurring and the threat of resurgent epidemic remains. A safe and effective vaccine, therefore, is still needed as a means to prevent and control Zika’s spread and its consequent complications. The Walter Reed Army Institute of Research leveraged its long-standing expertise, infrastructure and partnerships in developing and testing vaccines against other flaviviruses to rapidly design, manufacture and evaluate an inactivated and purified whole Zika virus vaccine, adjuvanted with aluminium hydroxide gel. Throughout the development and testing of this vaccine, we continually searched the biomedical literature for new information on Zika virus and its countermeasures. We searched and reviewed the PubMed database for Zika-related articles using the key search terms: “Zika”, “flavivirus”, “congenital Zika syndrome”, “vaccine”, “Zika vaccine” and “flavivirus vaccine”. We additionally reviewed electronic updates from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the World Health Organization and the Pan-American Health Organization on the dynamic epidemiology of the Zika epidemic. We also tracked the initiation and progress of other Zika clinical trials on ClinicalTrials.gov. A number of Zika vaccine platforms have demonstrated efficacy in pre-clinical animal models.19–24 One study thus far25 has been published that reports on the safety and immunogenicity of a DNA vaccine. To date and to our knowledge, the current report represents the only inactivated Zika virus vaccine platform being tested in humans.

Added value

This study offers significant value to the ongoing effort to develop a preventive vaccine against Zika virus. To date there is one other study in publication that reports on the safety and immunogenicity of a Zika vaccine candidate. The whole inactivated virus platform on which our candidate is based has resulted in several safe and effective vaccines, including some licensed for other flaviviruses such as Japanese encephalitis and tick borne encephalitis.18

Interpretation

The findings from this first-in-human phase 1a double-blind, randomized, placebo controlled trial of an investigational purified inactivated Zika virus vaccine candidate (ZPIV) demonstrate a tolerable safety profile and immunogenicity characterized by neutralizing antibody titers that exceed the protective threshold observed in murine and non-human primate models. Additionally, the results of a passive antibody transfer experiment from the serum of vaccine recipients into mice suggests a potential mechanistic correlate of protection for this vaccine candidate. These results correlate4 well with the preclinical data and inform the science of Zika vaccines as a whole, but particularly the inactivated platform as a viable candidate for advanced development.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Proportion of Responders by MN50 Antibody Titer Threshold.

The figure presents seroconversion rates at each time point from enrollment through day 57 either at a 1:10 (A) or 1:100 (B) threshold. The peak seroconversion rate among ZPIV recipients was 72.7% (95% CI 59.0% to 83.9%), and 87.3% of ZPIV recipients (95% CI 75.5% to 94.7%) achieved a titer above the limit of detection at some point in time.

Figure S2. Association of Age and Day 57 MN50 Titer.

Neutralizing antibody titers measured by microneutralization assay negatively correlated with age across the entire aggregate dataset. R=−0.46 (P=.006)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a cooperative agreement (W81XWH-07-2-0067) between the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Inc., and the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD). The work was also funded by the US Defense Health Agency (0130602D16). This study was supported in part by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID) Preclinical Services Vaccine Testing Contracts HHSN272201200003I/HHSN27200007 and HHSN27200020 for the conduct of the IND-enabling GLP toxicology study and clinical sample testing. The work was also funded in part by the Vaccine Treatment Evaluation Unit (VTEU) at Saint Louis University (Contract HHSN2722013000021I). The network of VTEUs is supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, part of the National Institutes of Health.

Material has been reviewed by the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, which has no objection to its presentation and/or publication. The opinions or assertions contained herein are the private views of the author, and are not to be construed as official, or as reflecting true views of the Department of the Army or the Department of Defense. The investigators have adhered to the policies for protection of human subjects as prescribed in AR 70–25. The sponsor of the investigational new drug (IND) application for two of the studies (WRAIR and SLU) is the Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (DMID), National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID, Bethesda, MD). The BIDMC study is investigator-sponsored (Dr. Kathryn Stephenson). We are deeply appreciative of the efforts of the key members of the DMID/NIAID Sponsor team, including Dr. Robert Johnson, Dr. Kay Tomashek and Ms. Cathy Cai, who provided input on study design, monitoring, analysis and interpretation. We appreciate the technical and administrative support of Mr. Casey Storme. We also thank Dr. Karen Peterson for her helpful review and comments on the manuscript.

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and should not be construed as official or representing the views of the US Department of Defense or the Department of the Army. DHB reports grants from the Henry Jackson Foundation during the conduct of the study and grants from the NIH, Gates Foundation, amfAR, Henry Jackson Foundation, Janssen, Gilead, Novavax as well as personal fees from IGM Biosciences outside of the submitted work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors

KM and NLM lead the US Army ZPIV program and oversaw the network of clinical trials. LL, SLG, and KES were the principal investigators of the WRAIR, SLU, and BIDMC trials, respectively. SJT, KHE, RGJ, RAD, KM, and NLM developed the vaccine. RAD, KEM, JB, AB, KEM, RAL carried out the immunogenicity and other laboratory analyses. JB, JT, AEK and PD were responsible for the statistical analysis. KM, LL, SLG, KES, MLR, DFH, SJT, DHB and NLM designed the studies. RAL, PA, MB, CB, MS, and DHB designed and performed the adoptive transfer animal study. KM, LL, SLG, KES, ES, JT, JA, KM, MK, MLR, AH, CST, SW, TAC, AB, MW, VT contributed to study operations. All authors contributed to the writing and editing of the report and approved the final version.

Declaration of interests

None of the other authors have any disclosures or conflicts of interest to report.

Contributor Information

Kayvon Modjarrad, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Silver Spring, MD USA.

Leyi Lin, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Silver Spring, MD USA.

Sarah L George, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, Allergy and Immunology, Saint Louis University School of Medicine, Saint Louis, MO, USASaint Louis VA Medical Center, Saint Louis, MO, USA.

Kathryn E Stephenson, Center for Virology and Vaccine Research, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA.

Kenneth H Eckels, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Silver Spring, MD USA.

Rafael A De La Barrera, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Silver Spring, MD USA.

Richard G Jarman, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Silver Spring, MD USA.

Erica Sondergaard, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Silver Spring, MD USA.

Janice Tennant, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, Allergy and Immunology, Saint Louis University School of Medicine, Saint Louis, MO, USA.

Jessica Ansel, Center for Virology and Vaccine Research, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA.

Kristin Mills, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Silver Spring, MD USA.

Michael Koren, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Silver Spring, MD USA.

Merlin L Robb, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Silver Spring, MD USAHenry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Jill Barrett, The Emmes Corporation, Rockville, MD, USA.

Jason Thompson, The Emmes Corporation, Rockville, MD, USA.

Alison E Kosel, The Emmes Corporation, Rockville, MD, USA.

Peter Dawson, The Emmes Corporation, Rockville, MD, USA.

Andrew Hale, University of Vermont Medical Center and Larner College of Medicine, Burlington, VT, USA.

C Sabrina Tan, Center for Virology and Vaccine Research, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA.

Stephen Walsh, Center for Virology and Vaccine Research, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA.

Keith E Meyer, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, Allergy and Immunology, Saint Louis University School of Medicine, Saint Louis, MO, USA.

James Brien, Department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology, Saint Louis University School of Medicine, Saint Louis, MO, USA.

Trevor A Crowell, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Silver Spring, MD USAHenry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Azra Blazevic, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, Allergy and Immunology, Saint Louis University School of Medicine, Saint Louis, MO, USA.

Karla Mosby, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, Allergy and Immunology, Saint Louis University School of Medicine, Saint Louis, MO, USA.

Rafael A Larocca, Center for Virology and Vaccine Research, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA.

Peter Abbink, Center for Virology and Vaccine Research, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA.

Michael Boyd, Center for Virology and Vaccine Research, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA.

Christine A Bricault, Center for Virology and Vaccine Research, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA.

Michael Seaman, Center for Virology and Vaccine Research, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA.

Anne Basil, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Silver Spring, MD USAHenry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Melissa Walsh, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Silver Spring, MD USAHenry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Veronica Tonwe, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Silver Spring, MD USAHenry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Daniel F Hoft, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, Allergy and Immunology, Saint Louis University School of Medicine, Saint Louis, MO, USASaint Louis VA Medical Center, Saint Louis, MO, USA.

Stephen J Thomas, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Silver Spring, MD USA.

Dan H Barouch, Center for Virology and Vaccine Research, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA.

Nelson L Michael, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Silver Spring, MD USA.

References

- 1.Brasil P, Pereira JP, Jr, Raja Gabaglia C, et al. Zika Virus Infection in Pregnant Women in Rio de Janeiro - Preliminary Report. N Engl J Med. 2016 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Honein MA, Dawson AL, Petersen EE, et al. Birth Defects Among Fetuses and Infants of US Women With Evidence of Possible Zika Virus Infection During Pregnancy. JAMA. 2017;317:59–68. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.19006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johansson MA, Mier-y-Teran-Romero L, Reefhuis J, Gilboa SM, Hills SL. Zika and the Risk of Microcephaly. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1605367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Melo AS, Aguiar RS, Amorim MM, et al. Congenital Zika Virus Infection: Beyond Neonatal Microcephaly. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73:1407–16. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.3720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mlakar J, Korva M, Tul N, et al. Zika Virus Associated with Microcephaly. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:951–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rasmussen SA, Jamieson DJ, Honein MA, Petersen LR. Zika Virus and Birth Defects–Reviewing the Evidence for Causality. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1981–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1604338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silasi M, Cardenas I, Kwon JY, Racicot K, Aldo P, Mor G. Viral infections during pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2015;73:199–213. doi: 10.1111/aji.12355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Plotkin SA. Rubella eradication. Vaccine. 2001;19:3311–9. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(01)00073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brasil P, Sequeira PC, Freitas AD, et al. Guillain-Barre syndrome associated with Zika virus infection. Lancet. 2016;387:1482. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30058-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cao-Lormeau VM, Blake A, Mons S, et al. Guillain-Barre Syndrome outbreak associated with Zika virus infection in French Polynesia: a case-control study. Lancet. 2016;387:1531–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00562-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dos Santos T, Rodriguez A, Almiron M, et al. Zika Virus and the Guillain-Barre Syndrome - Case Series from Seven Countries. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1598–601. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1609015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parra B, Lizarazo J, Jimenez-Arango JA, et al. Guillain-Barre Syndrome Associated with Zika Virus Infection in Colombia. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1513–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1605564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barouch DH, Thomas SJ, Michael NL. Prospects for a Zika Virus Vaccine. Immunity. 2017;46:176–82. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marston HD, Lurie N, Borio LL, Fauci AS. Considerations for Developing a Zika Virus Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1209–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1607762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faria NR, Azevedo R, Kraemer MUG, et al. Zika virus in the Americas: Early epidemiological and genetic findings. Science. 2016;352:345–9. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf5036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larocca RA, Abbink P, Peron JP, et al. Vaccine protection against Zika virus from Brazil. Nature. 2016;536:474–8. doi: 10.1038/nature18952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abbink P, Larocca RA, De La Barrera RA, et al. Protective efficacy of multiple vaccine platforms against Zika virus challenge in rhesus monkeys. Science. 2016;353:1129–32. doi: 10.1126/science.aah6157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Plotkin SA. Correlates of protection induced by vaccination. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2010;17:1055–65. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00131-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dowd KA, Ko SY, Morabito KM, et al. Rapid development of a DNA vaccine for Zika virus. Science. 2016;354:237–40. doi: 10.1126/science.aai9137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sumathy K, Kulkarni B, Gondu RK, et al. Protective efficacy of Zika vaccine in AG129 mouse model. Sci Rep. 2017;7:46375. doi: 10.1038/srep46375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muthumani K, Griffin BD, Agarwal S, et al. In vivo protection against ZIKV infection and pathogenesis through passive antibody transfer and active immunisation with a prMEnv DNA vaccine. npj Vaccines. 2016:1. doi: 10.1038/npjvaccines.2016.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richner JM, Himansu S, Dowd KA, et al. Modified mRNA Vaccines Protect against Zika Virus Infection. Cell. 2017;168:1114–25 e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richner JM, Jagger BW, Shan C, et al. Vaccine Mediated Protection Against Zika Virus-Induced Congenital Disease. Cell. 2017;170:273–83 e12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pardi N, Hogan MJ, Pelc RS, et al. Zika virus protection by a single low-dose nucleoside-modified mRNA vaccination. Nature. 2017;543:248–51. doi: 10.1038/nature21428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tebas P, Roberts CC, Muthumani K, et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of an Anti-Zika Virus DNA Vaccine - Preliminary Report. N Engl J Med. 2017 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Proportion of Responders by MN50 Antibody Titer Threshold.

The figure presents seroconversion rates at each time point from enrollment through day 57 either at a 1:10 (A) or 1:100 (B) threshold. The peak seroconversion rate among ZPIV recipients was 72.7% (95% CI 59.0% to 83.9%), and 87.3% of ZPIV recipients (95% CI 75.5% to 94.7%) achieved a titer above the limit of detection at some point in time.

Figure S2. Association of Age and Day 57 MN50 Titer.

Neutralizing antibody titers measured by microneutralization assay negatively correlated with age across the entire aggregate dataset. R=−0.46 (P=.006)