Abstract

Non-toxicity, biodegradability and non-carcinogenicity of the natural pigments, dyes and colorants make them an attractive source for human use. Bacterial pigments are colored metabolites secreted by bacteria under stress. The industrial uses of bacterial pigments have increased many folds because of several advantages over the synthetic pigments. Among natural resources, bacterial pigments are mostly preferred because of simple culturing and pigment extraction techniques, scaling up and being time economical. Generally, the bacterial pigments are safe for human use and therefore have a wide range of applications in pharmaceutical, textile, cosmetics and food industries. Therapeutic nature of the bacterial pigments is revealed because of their antimicrobial, anticancer, cytotoxic and remarkable antioxidant properties. Owing to the importance of bacterial pigments it was considered important to produce a comprehensive review of literature on the therapeutic and industrial potential of bacterial pigments. Extensive literature has been reviewed on the biomedical application of bacterial pigments while further opportunities and future challenges have been discussed.

Keywords: Bacteria, Natural pigments, Antibacterial, Anticancer, Antileishmania, Antioxidant

Introduction

Non-toxicity, biodegradability and non-carcinogenicity of the natural dyes and colorants derived from natural flora and fauna make them an attractive source for human use (Joshi et al. 2003). Synthetically synthesized pigments are mostly criticized because of various public and scientific concerns due to which the market value is also reducing (Koes et al. 1994). US environmental activists in 1960 demonstrated against the synthetic food additives and colorants and his idea spread out globally. Because of its nutritional value, the activist campaigned for the use of natural pigments and colorants. Because of his campaign, the use of colorants and additives shifted towards natural sources, and currently, natural pigments are widely used nowadays (Krishnamurthy et al. 2002). Pharmacological and other viable health advantages of natural pigments over synthetic pigments have further boosted their use in market. Pigment, colorants and dyes isolated from the natural sources are widely used in everyday life such as the use of pigments in agriculture practices, paper production, textile industries and food production (Cserháti 2006). Green technology favor less toxic and more natural material for the production line. Some synthetic dyes and colorants are prohibited in the market because of their carcinogenic precursor product and disposal effects of their industrial waste in the environment. On the other hand, natural pigments, colorants and dyes have high market value because of their various advantages such as safety and also have potential biological activities such as anticancer and antioxidant. These factors increase the thrust of exploring new sources of natural pigments and food colorants. Some industries such as textile, cosmetics and food industry are now producing bacterial pigments on commercial scale (Dufossé 2006). Natural colorants actually increase market value of a product. The increasing applications of natural pigments in different areas such as food, cosmetics, textile and pharmaceutical industries turned researches to find potential compounds in these pigments that have important therapeutic applications. The toxic effect of many drugs compel pharmacist to search new sources of drugs that are safer in use and antibiotic of broad spectrum potential. The current increase in the drug resistance in pathogen might be due to the increased use of present antibiotics (Gupte et al. 2002). To overcome such type of drug resistance by pathogens, antibiotics demand to be developed from new sources. Currently, for the cancer that is the leading causative agent of death there is no reasonable drug available (Taylor et al. 2007). The demand for new drug expands with the increase spreading of new pathogens and very restricted availability for the control of drugs resistance of in-cancer patients. Products of microbes and actinobacteria in particular, isolated from novel ecosystem can be a potential alternative source for new drugs. Various studies reported the screening of pigments isolated from various soil bacteria (Mellouli et al. 2003).

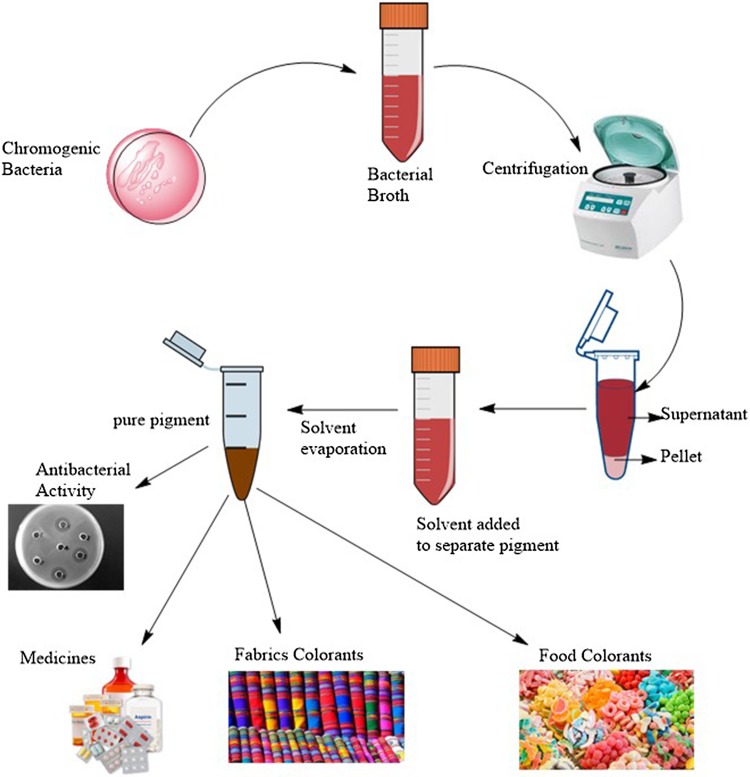

Considering the potential pharmacological potential of bacterial pigments, it was felt necessary to write a detailed review about various aspects of therapeutic abilities of these natural bacterial pigments. Extensive literature was studied for this purpose to cover nearly all health-related benefits of bacterial pigments. In this review, we cover many important aspects such as anticancer ability, antileishmanial ability, antibacterial ability and antioxidant potential of bacterial pigments. Despites health benefits, some applications of these pigments in food and textile industry have also been discussed. Schematic representation of pigment extraction is shown in Fig. 1 and the potential beneficial aspects are discussed below.

Fig. 1.

Extraction of bacterial pigments

Why natural pigments?

The environmental safety, conservation and awareness have switched the trend towards the natural sources for coloring agents. Non-toxicity, biodegradability and non-carcinogenicity of the natural dyes and colorants derived from natural flora and fauna make them an attractive source for human use (Joshi et al. 2003). Anthraquinones and flavonoids are natural products that are traditionally used as coloring agents which are commonly derived from animals and plants. Currently, as the trend is shifting towards the natural sources for the eco-friendly compounds, natural colorants are leading the market demand over the passage of time. These natural colorants and pigments are derived from many different sources such as insects, ores microbes and plants. Among these sources, microbes and bacteria in particular have the capacity to synthesize a wide of range secondary metabolites and pigments. Pigments extracted from bacteria have a diverse range of commercial applications (Table 1). It is an emerging field and is in the stage of infancy. Efforts are needed to develop a cheap media for bacterial growth to reduce its cost and make it feasible for commercial production (Joshi 2003; Venil and Lakshmanaperumalsamy 2009; Ahmad et al. 2012).

Table 1.

Pigment producing microorganisms (Konuray and Erginkaya 2015)

| Microorganism | Pigment color | Applications | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurospora sp. | Orange–red | Anticancer | Huang (1964), Gerber (1975) |

| Achromobacter | Pink, orange, red | Anticancer; Antimalarial | Duerre and Buckley (1965), Kawauchi et al. (1997) |

| H. alexandrinus | Red | Antiplasmodial | Asker and Ohta (2002), Yamamoto et al. (1999) |

| Bacillus sp. | Pink, orange, Yellow | Antibacterial | Khaneja et al. (2010), Gerber (1975) |

| Brevibacterium sp. | Orange | Antioxidation | Guyomarc’h et al. (2000), Kim et al. (1999) |

| C. michigannisse | Creamish, Grayish, | Anticancer | Konuray and Erginkaya (2015), Lazaro et al. (2002) |

| Pseudomonas sp. | Brown, Yellow–green, | Antibiotic | Howarth and Dedman (1964), Kim et al. (2007) |

| Arthrobacter | Yellow | Cytotoxic | Galaup et al. (2015) |

| C. infirmominiatum | Red | Antibacterial | Herz et al. (2007) |

| R. maris | Deep red | Antibiotic | Ichiyama et al. (1989), Kim et al. (2007) |

| Streptomyces sp. | Blue, red, yellow | Antibiotic | Konuray and Erginkaya (2015), Palanichamy et al. (2011) |

| Aspergillus sp. | Red, Orange | Antibacterial | Joshi et al. (2003) |

| A. glaucus | Dark red | Anticancer | Konuray and Erginkaya (2015) |

| B. trispora | Cream | Tambjamines (BE-18591, Antibiotic) | Joshi et al. (2003) |

| H. catenarium | Red | Protection from UV irradiation | Joshi et al. (2003), Gerber (1975) |

| H. gramineum | Red | Protection from UV irradiation | Joshi et al. (2003), Kim et al. (2007) |

| H. cynodontis | Bronze color | Antibiotic | Joshi et al. (2003), Gerber and Gauthier (1979) |

| H. avenae | Bronze color | Antibiotic | Joshi et al. (2003) |

| H. catenarin | Dark maroon | Anti-inflammatory, | Joshi et al. (2003) |

| M. purpureus | Red, orange, yellow | Anticancer; | Mukherjee and Singh (2011) |

| P. cyclopium | Orange | Antiproliferative | Mapari et al. (2009) |

| P. nalgiovense | Red | Antiproliferative | Chávez et al. (2011) |

| Cryptococcus sp. | Red | Algicidal | Joshi et al. (2003) |

| P. rhodozyma | Orange | Antiprotozoan | Miller et al. (1976), Johnson (2003), Yadav et al. (2014) |

| Rhodotorula sp. | Orange/red, Yellow | Anticancer | Yadav et al. (2014) |

| Y. lipolytica | Brown | Antiprotozoan | Carreira et al. (2001a, b) |

| D. salina | Red, Orange | Antiprotozoan | Arun and Singh (2013), Houbraken et al. (2012) |

| S. roseus | Reddish-pink | Anticancer; Algicidal | Davoli and Weber (2002) |

| P. chrysogenum | Yellow | Algicidal | Chávez et al. (2011); Houbraken et al. (2012) |

Compounds such as flavonoids, alkaloids and isoprenoids isolated from natural sources were used for fragrance, flavors and as colorants in ancient time. The trend of using natural products switched to synthetic products due to low availability and high price of the natural pigments, colorants and dyes in the previous decades. But the various safety and other toxic issues in synthetic pigments, the market once again is switching towards the natural pigments (Sowbhagya and Chitra 2010). One of the important advantages of the natural pigments is its pharmaceutical applications (Table 1). A lot of work is continued to explore a novel bacteria that can produce commercially important pigments (Li and Vederas 2009).

Pharmacological applications of bacterial pigments

Previous studies indicated that bacterial secondary metabolites and pigments in particular have immense importance in the treatment of various diseases and also have properties such as anticancer, antibiotic and immunosuppressive compounds. Various secondary metabolites that have potential therapeutic activities are phenols, quinols, flavonoids, polyketones, peptides, terpenoids, steroids and alkaloids. These compounds have remarkable anticancer, immunosuppressive, inflammatory, antimicrobial and antioxidant activities (Korkina 2007). Recently, a review has been published on the biosynthesis of these compounds from bacteria (Singh et al. 2017). With the passage of time the investigation of new, vital and bioactive compounds from bacterial sources increased as compared to other sources (Soliev et al. 2011). For example, anthocyanin, a compound that have diverse biological activities and positively affect health and have the property to reduce the risk of cancer (Kong et al. 2003; Katsube et al. 2003; Lazzè et al. 2004; Martin et al. 2003; Kim et al. 2012). Anthocyanin is also involved in reducing the chances of inflammatory insults and have role in modulating the immune response (Youdim et al. 2002; Wang and Mazza 2002) (Table 2). As another example, violacein has the properties such as antiviral (Sánchez et al. 2006), anticancer (Ferreira et al. 2004; Kodach et al. 2006), antiprotozoan (Matz et al. 2004), antioxidant activities (Konzen et al. 2006) and antibacterial activities (Lichstein and Van De Sand 1946; Nakamura et al. 2002) (Table 2). There are various other examples of bacterial pigments for the treatment of various diseases such as a compound prodigiosin, isolated from the Serratia culture broth have the cytotoxic as well as antiproliferative potential in various cell lines such as renal, colon, lung and ovarian cell lines (Fig. 2). Prodigiosin is also found in the B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients (Kim et al. 2003; Pandey et al. 2007; Campas et al. 2003). This compound is also reported for the treatment of diabetes mellitus (Kim et al. 2003). Another compound isolated from the yellow–orange pigment flexirobin, ant342 (F-YOP) from Flavobacterium sp. has been reported for the chemotherapy of tuberculosis (Richard 1992). If further research is performed on these bacterial pigments, these can open new ways of treating various deadly diseases.

Table 2.

Biological applications of some important bacterial pigments

| Compound name | Biological applications | Source | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anthocyanin | Cancer; inflammation; immune response | Bacteria | Kong et al. (2003), Katsube et al. (2003), Lazzè et al. (2004), Martin et al. (2003), Kim et al. (2012), Youdim et al. (2002), Wang and Mazza (2002) |

| Violacein | Antiviral; anticancer; antiprotozoan antibacterial activities | Bacteria | Sánchez et al. (2006), Ferreira et al. (2004), Kodach et al. (2006), Matz et al. (2004), Konzen et al. (2006), Lichstein and Van De Sand (1946), Nakamura et al. (2002) |

| Prodigiosin | Cytotoxic; antiproliferative potential; diabetes mellitus; B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients | Bacteria | Kim et al. (2003), Pandey et al. (2007), Campas et al. (2003), Kim et al. (2003) |

| Ant342 (F-YOP) | Chemotherapy of tuberculosis | Bacteria | Richard (1992) |

Fig. 2.

Applications of bacterial pigments in therapeutics

Anticancer potential of bacterial pigments

Cancer is one of the most prominent causes of death in both male and female around the globe and around 6 million people are victim of this disease each year. Many drugs against cancer are developed and are in trials to date. But side effects and resistance to these drugs have also been discovered. Apoptosis is now one of the novel methods recognized to kill tumors without causing resistance or any other side effects (Lowe and Lin 2000). Apoptosis is currently focused for cancer treatment (McConkey et al. 1996); the present anticancer drugs have been reported to trigger apoptosis of cancer cells that encourage the discovery of many other potentially novel compounds having same mechanisms from various sources such as marine organisms. Marine organisms are a diverse source of various natural products (Cragg and Newman 1999; Schwartsmann et al. 2000). About 3000 compounds in past few years have been reported from various marine sources while some of them entered into clinical trials (Schwartsmann et al. 2001; Carte 1996). Oceans contain millions of species (Nuijen et al. 2000) that could be the potential source of various novel therapeutic agents (Fenical 1997).

Many studies reported the anticancer ability of bacterial pigments, for example, Lin et al. (2005) studied the effect of pigments extracted from 12 different bacterial strains. They reported strong cytotoxic effect of these extracts on HeLa cells and showed that the extract have significantly inhibited the growth of HeLa cells in a time-dependent manner (Lin et al. 2005). Many other cell lines tested against bacterial pigments for cytotoxic potential are listed in Table 3, in which significant cytotoxic activity was observed against these cell lines (Choi et al. 2015). Other studies reported the potential use of anthocyanin, a compound that has diverse biological activities and positively affects health and has the property to reduce the risk of cancer (Kong et al. 2003; Katsube et al. 2003; Lazzè et al. 2004; Martin et al. 2003; Kim et al. 2012). Another example of bacterial pigments used for the treatment of various diseases is a compound prodigiosin, isolated from the Serratia culture broth. This compound has cytotoxic as well as antiproliferative potential in various cell lines such as renal, colon, lung and ovarian cell lines. Prodigiosin is also found in the B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients (Kim et al. 2003; Pandey et al. 2007; Campas et al. 2003; Ahmad et al. 2012). The cytotoxic and antiproliferative potentials of the analogs of prodigiosin and the derivatives of the synthetic indole of prodigiosin (Pandey et al. 2007) are well studied (Table 2). The potential cytotoxic effect of this compound has also been reported in cell lines cultured from tumors and also have significant activity against cancer cells derived from B-cell chronic lymphocytic of leukemia patients (Campas et al. 2003). Another compound (violacein) in bacterial pigments has the anticancer and antioxidant activity properties (Konzen et al. 2006; Ahmad et al. 2012). Despite these few compounds, there may be hundreds of other compounds in bacterial pigments that could have strong cytotoxic activity needs to be discovered (Table 3).

Table 3.

Cell lines tested against bacterial pigments for cytotoxicity

| Cell type | Source of cells | Cell line | Activity of pigment against cell lines | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | Human | MOLT-4 | Found cytotoxic | Melo et al. (2000) |

| Fibroblast-like cell line from lung tissue | Chinese hamster | V79 | Caused apoptosis | Melo et al. (2000) |

| Colon cancer | Human | KM12 | Found cytotoxic | Melo et al. (2000) |

| Non-small-cell lung cancer | Human | NCI- H460 |

Found cytotoxic | Melo et al. (2000) |

| Kidney epithelial cells | Monkey | MA104 | Found to inhibit cells growth | Andrighetti-Fröhner et al. (2003) |

| Hela-derived | Human | Hep2 | Found to inhibit cells growth | Andrighetti-Fröhner et al. (2003) |

| Fetal kidney | Monkey | FRhK-4 | Found to inhibit cells growth | Andrighetti-Fröhner et al. (2003) |

| Kidney | Monkey | Vero | Found to inhibit cells growth | Andrighetti-Fröhner et al. (2003) |

| Promyelocytic leukemia | Human | HL60 | Caused apoptosis | Ferreira et al. (2004) |

| Chronic myelogenic leukemia | Human | U937 | Less effective Compared to HL60 |

Ferreira et al. (2004) |

| Lymphoma | Human | K562 | Less effective Compared to HL60 |

Ferreira et al. (2004) |

| Choroidal melanoma | Human | OCM-1 | Moderately cytotoxic | Saraiva et al. (2004) |

| Uveal melanoma | Human | 92.1 | Moderately cytotoxic | Saraiva et al. (2004) |

| Colorectal adenocarcinoma | Human | DLD1 | Found effective | Kodach et al. (2005) |

| Colorectal adenocarcinoma | Human | SW480 | Found effective | Kodach et al. (2005) |

| Colorectal adenocarcinoma | Human | HCT116 | Found effective | Kodach et al. (2005) |

| Cervical epithelial cells | Human | HeLa | Caused apoptosis | Lin et al. (2005) |

| Heterogeneous epithelial colorectal adenocarcinoma | Human | Caco-2 | Found effective | Kodach et al. (2005), De Carvalho et al. (2006) |

| Colorectal adenocarcinoma | Human | HT29 | Caused cytotoxicity | De Carvalho et al. (2006) |

| Erythroleukemia | Human | TF1 | Caused cell death | Queiroz et al. (2012) |

Antileishmanial efficiency of bacterial pigments

Leishmaniasis, a fatal and disfiguring disease caused by a protozoan leishmania. More than 12 million people are affected by this disease worldwide. The drugs developed 50 years ago for the treatment of the disease are not working efficiently and have toxic effects. In Brazil, the most common is Leishmania amazonensis and is linked with different disease forms, including hyperergic mucocutaneous, cutaneous, visceral leishmaniasis and anergic diffuse cutaneous (Leon et al. 1990, 1992).

Antileishmanial activity of bacterial pigments was only reported by Leon et al. (Leon et al. 2001). They reported that a compound named violacein showed significant antileishmanial activity. They recorded EC50/24 h value of 4.3 ± 1.15 μmol/L. They compared the value with pentamidine, a drug that is used for the treatment of leishmaniasis. They found that violacein is less active as compared to pentamidine. When pentamidine is used at a concentration of 16.8 μmol/L, it inhibits 100% promastigotes while violacein is required at a concentration of 460.8 μmol/L to achieve same inhibition of promastigotes. They further included that although it is less active but has no side effects as compared to pentamidine that has toxic effects (Melo et al. 2000).

Antibacterial properties of pigments

Bacterial pigments are reported to have antibacterial activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. August et al. (2000) reported that violet pigment isolated from Chromobacterium violaceum has broad spectrum antibacterial activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria particularly S. aurous and S. typhi (August et al. 2000). Similar results were studied by Suresh et al. (Suresh et al. 2015). They found that the red pigment produced by H. alkaliphilus MSRD1 has strong antibacterial activity against S. aureus, S. typhi, K. pneumonia, E. coli and Salmonella paratyphi. The summarized antibacterial results (Suresh et al. 2015) are given in Table 4.

Table 4.

Antibacterial activities of bacterial pigments

| Activity (zone of inhibition in mm) | References | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K. neumoniae | S. aureus | P. aeruginosa | V. cholerae | S. flexneri | S. typhi | B. megaterium | E. coli | B. subtilis | B. cereus | S. paratyphi | S. faecalis | |

| 7 | 16 | – | – | – | 14 | – | 6 | – | – | 8 | – | Suresh et al. (2015) |

| 21 | 19 | 11 | 12 | 9 | 12 | 24 | 13 | 21 | 22 | – | – | Rashid et al. (2014) |

| 21 | 18 | 21 | 27 | 24 | 25 | 20 | 24 | 21 | 15 | – | – | Rashid et al. (2014) |

| 24 | 28 | 32 | 31 | 30 | 32 | 28 | 34 | 24 | 25 | – | – | Rashid et al. (2014) |

| 30 | 29 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 28 | 34 | 26 | 30 | 30 | – | – | Rashid et al. (2014) |

| 27 | 25 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 21 | 31 | 19 | 27 | 33 | – | – | Rashid et al. (2014) |

| 18 | 19 | 31 | 32 | 31 | 26 | 16 | 27 | 18 | 16 | – | – | Rashid et al. (2014) |

| 14 | 12 | 14 | 17 | 18 | 16 | 15 | 13 | 14 | 12 | – | – | Rashid et al. (2014) |

| 16 | 11 | 12 | 14 | 15 | 11 | 14 | 16 | 16 | 10 | – | – | Rashid et al. (2014) |

| 12 | 17 | 12 | 13 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 9 | 12 | 15 | – | – | Rashid et al. (2014) |

| 35 | 34 | 38 | 39 | 38 | 30 | 31 | 41 | 35 | 29 | – | – | Rashid et al. (2014) |

| 15 | 14 | 9 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 16 | 11 | 15 | 15 | – | – | Rashid et al. (2014) |

| 27 | 31 | 38 | 42 | 39 | 36 | 33 | 34 | 27 | 34 | – | – | Rashid et al. (2014) |

| 11 | 8 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 23 | 12 | 25 | 11 | 14 | – | – | Rashid et al. (2014) |

| 16 | 16 | 10 | 13 | 15 | 14 | 18 | 11 | 16 | 18 | – | – | Rashid et al. (2014) |

| 41 | 39 | 32 | 36 | 45 | 46 | 44 | 38 | 41 | 35 | – | – | Rashid et al. (2014) |

| – | 29.3 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Radjasa et al. (2009) |

| – | 6.5 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 7.5 | Mohana et al. (2013) |

| – | 7.9 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 8.5 | Mohana et al. (2013) |

| – | 8.7 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 9.2 | Mohana et al. (2013) |

| – | 9.5 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 10.5 | Mohana et al. (2013) |

| – | 10.8 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 13 | Mohana et al. (2013) |

| – | 12.5 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 15 | Mohana et al. (2013) |

| – | 18.5 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 22.2 | Mohana et al. (2013) |

| – | 6.7 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 6.9 | Mohana et al. (2013) |

| – | 7.6 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 7.8 | Mohana et al. (2013) |

| – | 8 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 8.7 | Mohana et al. (2013) |

| – | 9.5 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 9.5 | Mohana et al. (2013) |

| – | 10.5 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 10.5 | Mohana et al. (2013) |

| – | 18.5 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 11.8 | Mohana et al. (2013) |

| – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 22.2 | Mohana et al. (2013) |

| 2 | 2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 10 | 5 | – | – | Banerjee et al. (2011) |

Rashid et al. (2014) determined antibacterial activity of pigments isolated from fifteen different bacteria. In their study, they reported the antibacterial effect of pigments of different isolates against nine different Gram-positive and Gram-negative human pathogenic bacterial strains. The findings of their study are given in Table 4. Previous literature reported by Rashid et al. (2014) showed that the antibacterial activity of the pigments isolated from different bacteria was more effective against Gram-negative pathogenic strains than Gram-positive. (Rashid et al. 2014).

Monascus pigments that are usually yellow, orange and red in color are reported to have weak antimicrobial activity (Kim et al. 2006). Another study performed by Cheng and Tseng (Chen and Tseng 1989) showed that Monascus purpureus pigments exhibited antibacterial activity against S. aureus (Chen and Tseng 1989). Violacein, an active compound of bacterial pigments, is reported to have antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive bacteria and tend to inhibit their growth except Clostridium welchii (Duran et al. 2012). Umadevi and Krishnaveni (2013) also observed positive antibacterial activity of pigments against different human pathogenic bacterial strains such as Klebsiella sp., Staphylococcus sp., Pseudomonas sp. and Escherichia sp. They also found their sample negative against Streptococcus sp. (Umadevi and Krishnaveni 2013). Study performed by Radjasa et al. (2009) attributed the antibacterial potential of pigment isolated from a bacterial strain. They showed that the pigment is significantly active against a human pathogenic strain Staphylococcus aureus. Mohana et al. (2013) studied antibacterial activity of various bacterial pigments against two human pathogenic bacterial strains, S. faecalis and Staphylococcus aureus. Banerjee et al. (2011) suggested that the isolated pigment has antibacterial activity against S. aureus, M. lutea, K. pneumonia, B. cereus and B. subtilis. They also reported their isolated pigment is inactive against S. cerevisiae, A. niger, P. aeruginosa, S. typhi and E. coli (Banerjee et al. 2011). These studies showed that pigments extracted from bacteria have potential bactericidal activity against various human pathogenic strains. Activities as zone of inhibitions, measured in millimeter are given in Table 4.

Antioxidant capacity of bacterial pigments

Carotenoids, one of the pigments of natural origin plays a vital role and are present in human diet positively because of their properties, e.g., action as antioxidant, provitamin or possibly their role in tumor inhibition (Joshi et al. 2003; Koes et al. 1994; Kim et al. 2003). There has been an exponential increase of commercial interest in natural sources during the past few years because of the scientific evidences highlighting the benefits of natural dyes in animal and human health (Nakamura et al. 2002). The utilization of carotenoid-rich diet has been epidemiologically linked with lower disease risk (Kodach et al. 2006). Therefore, carotenoids are considered as one of the most valued classes of compounds for commercial applications, e.g., in chemical, pharmaceutical feed and food industries (Koes et al. 1994).

The biosynthesis of carotenoids is characteristic of the genus Rhodotorula (Koes et al. 1994; Kodach et al. 2006). Effectively identified as orange/red, yellow colonies. The core carotenoids synthesized in Rhodotorula species are torulene, torularhodin and carotene and small amount of carotene (Koes et al. 1994; Joshi et al. 2003). Less explored bacterial carotenoids are torulene and torularhodin while more data are available for nutraceutical carotenoids, e.g., lycopene, carotene, etc. A small number of substances were depicted as “non-familiar” carotenoids, e.g., torularhodin, having provitamin A like activities.

Numerous microorganism’s genera produce it in large amount, e.g., up to 0.1% of the dry weight of cell, possibly as a defense against free radicals and photo oxidation. Considerable antioxidant activity is shown by torularhodin (Ungureanu and Ferdes 2012) that stabilizes the membranes under stress conditions. The beneficial side of these carotenoids is there use as hormone and vitamin A and their antioxidant and anti-aging capability. They play a role in immune system enhancement and prevention of certain type of cancer (Matz et al. 2004). Torularhodin shows considerable antioxidant activities and is a unique carotenoid with carboxylic acid (Lichstein and Van De Sand 1946). For industrial applications, the most important carotenoid of genus R. mucilaginosa is torulene. The carotenoids having provitamin A like activity are differentiated by carboxylic group and are used as color additives for cosmetic and food. This makes torulene and torularhodin a hot topic for research in carotenoid biotechnology. It has been reported that the most important pigment torularhodin protects from oxidative stress (Matz et al. 2004).

As indicated by researchers, during oxygen loading, R. glutinis produces more torularhodin than carotene. Therefore, it can be assumed that in yeast cells, torularhodin show protection against active oxygen species (Matz et al. 2004; Lichstein and Van De Sand 1946). Potential effects of torulene and torularhodin on human health are unknown because of their absence in food material. However, the structural characterization of these carotenoids and consideration of their anticancer and other activities supports their use in cosmetics, food and feed. As a matter of fact, some yeast species having these carotenoids is consumed by animals, e.g., Rhodotorula, e.g., chicken feed (muscle to fat ratio is expanded, improves appearance and builds the nutritious value of the meat). Torulene can be used as additive similarly as other hydrocarbon carotenoids, e.g., lycopene or beta carotene. On the other side, torularhodin being an acidic pigment can be used similarly as the major carotenoids of annatto extract, norbixin and bixin and can replace them in meat products for example.

Torularhodin and torulene can function as carotenoid antioxidants such as lycopene and astaxanthin, and again, the solubility is increased in aqueous formulation because of the presence of terminal carboxyl group so torularhodin can be used in particular formulations. In all cases, the formulation technology is same for all carotenoid: extract solution in edible oils, pigment’s oil-in-water emulsions, dispersible powders (Matz et al. 2004). Lycopene, the strongest antioxidant present, is a symmetrical tetraterpene made up of eight units of isoprene. Potential producer of lycopene is fungi of the genera Blakeslea and Phycomyces. Imidazole, pyridine, methyl heptenone and cyclase inhibitor 2-(4-chlorophenylthio)-triethylamine are the chemical stimulators (CPTA enhances accumulation of lycopene in P. blakesleeanus and Blakeslea trispora.

The most important particularities of lycopene are suppression of tumor cell proliferation, e.g., MSF-7 tumor cells and excessive singlet oxygen-quenching activity. Lycopene is also used in beverages, surimi, dairy products, sweets and chocolates, nutritional food, soups, cereals for breakfast, chips, spreads, pastas, snacks, and sauces (Chandi and Gill 2011). Astaxanthin is an interesting carotenoid having high market price and increasing demand and commonly found in freshwater and marine animals (Parajó et al. 1998; Johnson et al. 1978). Its use as a supplement for poultry feeds and aquaculture is because of the fact that it is deposited in egg yolks and flesh. Astaxanthin can be produced by biotechnological or chemical means (Mellouli et al. 2003).

Pigments isolated from pieces other than bacteria are also reported to have significant antioxidant activity such as the Phaffia rhodozyma (red yeast) is thought to be one of the best candidates for astaxanthin biotechnological production (Mellouli et al. 2003; Parajó et al. 1998). Over the last few years, a number of research works in this area has been reported. Few deal with the astaxanthin production optimization, either analyzing the effect of the operational conditions (pH, temperature, aeration) or by considering the concentration and type of the carbon source (Mellouli et al. 2003). The astaxanthin large-scale isolation from this yeast is desirable because of its use as a pigment source in diet of fishes (Parajó et al. 1998). Because of biological properties, violacein shows antitumoral and antioxidant activity and alongside its anticancer activity, it acts against many infectious diseases, e.g, trypanosomiasis, malaria and leishmaniasis.

Violacein working capacity in different biological environments and its application in the area of medicine along with toxicological data show its potential benefits in the future. Similarly, violacein is also used in industries, e.g., in textiles and cosmetics, along agroindustry (Duran et al. 2012). Few species of the genus Monascus are used as natural food additive in East Asia as a natural food colorant for red soybean cheeses, red rice wines and fish and meat products (Kim et al. 2006). The efficacy of carotenoids as singlet oxygen or free radical scavengers, as anticancer agents, as immune response stimulants and as coloring agents for soft drinks, baked goods cooked sausage, and cosmetics additives is well known (El-Banna et al. 2012).

Other applications of bacterial pigments

The use of bacterial pigments becomes doubled in the present decade because it offers various advantages over synthetic pigments (Hendry and Houghton 1996; S.editors 2009; Demain 1980). Due to its fast growth, easy propagation and culturing, easily grown on cheap media sources, simple culture techniques make it very attractive. Bacterial pigments are considered safe for human health and their increased usage in various industries such as food, cosmetics, textile and pharmaceuticals industries has been noticed (Boo et al. 2011; Katsube et al. 2003; Lazzè et al. 2004). Various applications are briefly discussed below (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Extraction and applications of bacterial pigments

Bacterial pigments in food industry

Food industry is aiming to develop food in various attractive colors. Industries are turning towards natural coloring agents because synthetic coloring agents and additives are found to have toxic health effects. Natural colorant is less abundant in market which increases the demand in food industry. This demand for natural pigments can be fulfilled by research in finding natural coloring agents (Aberoumand 2011). One way of obtaining natural food colorants is microbes which produce various colored pigments and have enormous advantages such as easy extraction, no seasonal variation, can be grown on cheap media and high yield in short time (Malik et al. 2012). Microorganisms are made to produce different colorants by inserting genes responsible for colored pigment production. Like natural food colorants these pigments are safe for human health and also preserve biodiversity, because release of harmful chemical into environment for the production of synthetic colorants can be stopped (Nagpal et al. 2011; Venil et al. 2013).

The high consumption of microbial pigments both as a nutritional supplement and colorants reflects its importance in the market and public well of using natural products. Limited number of colorants are approved for food industry in which some are recognized by their source of isolation such as vegetable juice and fruit juice while others have their specific chemical names, for example, canthaxanthin. Pigments which have their chemical names could be synthesized and isolated easily by any biotechnological sources. Major hurdle in the commercial production of these pigments is the technological limitations (Dufossé 2006).

Blue pigments along with other pigments of food grade have been isolated from soil bacteria that possess a natural color and potentially stable and has an excellent toxicological food profile. A team of researcher form University of science and technology East China reported that blue color pigment has a potential source of edible pigments (Zhang et al. 2006). The current food market is looking for natural food colorants such as quinoline yellow, tartrazine and sunset yellow instead of artificial colorants. The annual growth rate of European food market between 2001 and 2008 is just 1%, while on the other hand, the market growth rate of food colorants has raised 10–15%. Being an environmental friendly and other probiotic health benefits, bacterial pigments are preferred to use as colorants in food products (Nagpal et al. 2011). Fish industry is already using these microbial colorants, for example, in farmed salmon the pink color is enhanced by microbial colorants. The commercial potential of some food colorants as an antioxidant has also been reported (Dufossé 2006). Currently, the FDA approved marketed pigments include carotene from Blakeslea trispora and Monascus pigments, riboflavin from Ashbya gossypii, Arpink Red from Penicillium oxalicum and astaxanthin from Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous (Bohlke et al. 1999; Venil et al. 2013).

Application of pigments in textile industry

In textile industry, the production and consumption of pigments, dyes and dye precursors are approximately 1.3 million tons which cost almost U$ 23 billion, and most of these are synthetically produced. But synthetic dyes have various limitations such as safety concerns and generation of hazardous wastes. The production of natural colorants gained interest in recent years in textile industry (Mapari et al. 2005). Presently, coloring agents are produced largely from non-renewable sources such as fossil oil. Beside economic efficiency and technical advancement, synthetic pigments face various challenges such as human health and safety concerns, environmental toxicity and dependence on non-renewable resources. Commercial production of these pigments through fermentation can serve as a source of chemical modification which can produce wide varieties of different colorants (Ahmad et al. 2012). Fermentation of microbial pigments can be a valuable source for the production of colorants. Microorganisms can synthesize wide varieties of pigments such as rubramines, quinones, flavonoids and carotenoids and have higher yield and less amount of residues as compared to plant and other animals (Hobson 1998). Despite of natural pigments and colorants, antimicrobial and bright color has been reported in anthraquinone type of compounds which could be a potential source of antimicrobial textile material (Frandsen et al. 2006) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Applications of bacterial pigments

Prodigiosin, a bright red pigment, was isolated from vibrio sp. (Ahmad et al. 2012). And it was suggested that it has many applications in various fields such as textile and pharmaceuticals. In textile, prodigiosin can be used as dye for many silk, acrylics, nylon, wool, and fibers (Alihosseini et al. 2008). Pigments isolated from Serratia marcescens have the capability to color five different types of fabrics which include cotton, silk, polyester and polyester microfiber (Venil et al. 2013). The performance of dying depends on fibers and is different for every fiber. Colored fabrics have the capability to keep its color in sort of environmental conditions crocking/rubbing, washing and perspiration. Similar properties is also reported for another colorant Janthinobacterium lividum, which is used for dying vinylon, nylon, wool, cotton and silk (Shirata et al. 2000). To dye a material, it is boiled with pigment-producing bacterial cell or dipped in the pigment extract. The color intensity can be varied and it depends on the duration of dipping time and dye bath temperature. Dying efficiency of violacein (violet pigment) and prodigiosin (red pigment) has been tested in different fabrics and their results suggested that the red pigment prodigiosin has the ability to dye acrylic, and violacein was observed to dye jacquard rayon, and pure rayon and silk. Prodigiosin and violacein have application in batik (gown-like dress used in Asia) making (Ahmad et al. 2012).

Among these batiks, the most popular one includes flowers, leaves and the geometrical design. The design is first drawn by pencil on the fabric and then melted wax is applied over it the technique is usually known as “canting”. When the waxing process is completed then dyes or bacterial pigments are applied on the fabric with the help of brush. The tone of the color is adjusted by the addition of ethyl acetate or acetone. Ethyl acetate is generally used for purple and red color pigment, and acetone is used for yellow pigment. The material or fabrics is then immersed in the boiling water which contain fixing materials such as copper sulfate, iron sulfate and alum which not only remove wax but also fix the pigments on the fabrics. The fabric is than sun dried (Ahmad et al. 2012).

Challenges and opportunities

Other than the common advantages of the bacterial pigments such as easy extraction and eco-friendly synthesis, there is a massive potential of their use in various industries such as in pharmaceutical, food, textile and cosmetic. Bacteria are usually easy to culture and scaled up easily for large-level productions. The production of pigments can be enhanced by genetic or metabolic engineering. They are economical and free of the use of any hazardous chemicals. The metabolic engineering or synthetic biology can not only increase the production of bacterial pigment, but also could make bacteria (or microbes) as a common platform for the heterogenetic production of pigment from fungi, plant and animal, which will extensively expand the scale of bacterial pigments. To date, a very small percentage of the bacterial flora has been explored for the extraction and isolation of pigments. Hence, it can be inferred that further exploration of the novel bacterial strains can lead to the potential novel pigments which can have diverse uses.

It is estimated that only 1% of the microbial world has been explored while the rest can be explored for bacterial-based pigments. On the contrary, synthetic pigments are produced by the use of toxic chemicals that are harmful for the humans and environment. To overcome, we strongly recommend isolation of bacterial strains from novel environments and study them for bacterial pigments.

Among the major challenges to overcome for the commercialization and widespread applications of bacterial-based pigments, is the awareness of the fact that the bacterial-derived pigments are relatively safe to their synthetic counterparts. Despite of many applications, bacterial pigments are facing some challenges in their way of commercialization. The most serious challenge is the contamination of bacterial cultures. However, if proper practices are followed, sterile environment for the bacterial cultures can be maintained. Further research on the biomedical potential in terms of clinical trials on animals and human beings should be carried out to uncover the real potential of therapeutic bacterial derived pigments.

Concluding remarks

Bacterial pigments are actually colored secondary metabolites secreted during stress conditions. Bacterial pigments have diverse range of applications in various industries such as pharmaceutical, food and textile industries. Due to its potential activity against many human pathogenic bacterial strains, it can be a potential drug to cure patients infected with these pathogenic bacterial strains. Similar effects were observed for anticancer and antileishmanial activities. These bacterial pigments are active against some cell lines that mean if further research is performed on these pigments, these can help in the treatment of cancer. Bacterial pigments also showed strong antioxidant activity helpful in scavenging of free radicals. Despite of therapeutic applications, bacterial pigments also have applications in food and textile industries. In food and textile industries, these pigments are used as colorants. If further research is performed, these bacterial pigments can be of potential commercial interest.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Najeeb Ur Rehman, Phone: +96825446328, Email: najeeb@unizwa.edu.om.

Zabta Khan Shinwari, Email: shinwari2008@gmail.com.

Ahmed Al-Harrasi, Phone: +96825446328, Email: aharrasi@unizwa.edu.om.

References

- Aberoumand A. A review article on edible pigments properties and sources as natural biocolorants in foodstuff and food industry. World J Dairy Food Sci. 2011;6(1):71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad WA, Ahmad WYW, Zakaria ZA, Yusof NZ (2012) Application of bacterial pigments as colorant. In: Application of bacterial pigments as colorant. Springer, pp 57–74

- Alihosseini F, Ju KS, Lango J, Hammock BD, Sun G. Antibacterial colorants: characterization of prodiginines and their applications on textile materials. Biotechnol Prog. 2008;24(3):742–747. doi: 10.1021/bp070481r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrighetti-Fröhner CR, Antonio RV, Creczynski-Pasa TB, Barardi CRM, Simões CMO. Cytotoxicity and potential antiviral evaluation of violacein produced by Chromobacterium violaceum. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 2003;98(6):843–848. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762003000600023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arun N, Singh D. Differential response of Dunaliella salina and Dunaliella tertiolecta isolated from brines of Sambhar Salt Lake of Rajasthan (India) to salinities: a study on growth, pigment and glycerol synthesis. J Mar Biol Assoc India. 2013;55(1):65–70. doi: 10.6024/jmbai.2013.55.1.01758-11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- August P, Grossman T, Minor C, Draper M, MacNeil I, Pemberton J, Call K, Holt D, Osburne M. Sequence analysis and functional characterization of the violacein biosynthetic pathway from Chromobacterium violaceum. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2000;2(4):513–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asker D, Ohta Y. Production of canthaxanthin by Haloferax alexandrinus under non-aseptic conditions and a simple, rapid method for its extraction. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2002;58(6):743–750. doi: 10.1007/s00253-002-0967-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee D, Chatterjee S, Banerjee U, Guha AK, Ray L. Green Pigment from Bacillus cereus M116 (MTCC 5521): production parameters and antibacterial activity. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2011;164(6):767–779. doi: 10.1007/s12010-011-9172-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohlke K, Spiegelman D, Trichopoulou A, Katsouyanni K, Trichopoulos D. Vitamins A, C and E and the risk of breast cancer: results from a case-control study in Greece. Br J Cancer. 1999;79(1):23. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boo H-O, Hwang S-J, Bae C-S, Park S-H, Song W-S. Antioxidant activity according to each kind of natural plant pigments. Korean J Plant Resour. 2011;24(1):105–112. doi: 10.7732/kjpr.2011.24.1.105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campas C, Dalmau M, Montaner B, Barragan M, Bellosillo B, Colomer D, Pons G, Pérez-Tomás R, Gil J. Prodigiosin induces apoptosis of B and T cells from B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2003;17(4):746–750. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carte BK. Biomedical potential of marine natural products. Bioscience. 1996;46(4):271–286. doi: 10.2307/1312834. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carreira A, Ferreira L, Loureiro V. Production of brown tyrosine pigments by the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. J App Microbiol. 2001;90(3):372–379. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carreira A, Ferreira LM, Loureiro Vl. Brown pigments produced by Yarrowia lipolytica result from extracellular accumulation of homogentisic acid. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67(8):3463–3468. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.8.3463-3468.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandi GK, Gill BS. Production and characterization of microbial carotenoids as an alternative to synthetic colors: a review. Int J Food Prop. 2011;14(3):503–513. doi: 10.1080/10942910903256956. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chávez R, Fierro F, García-Rico RO, Laich F (2011) Mold-fermented foods: Penicillium spp. as ripening agents in the elaboration of cheese and meat products. In: Mycofactories. Bentham Science Publishers Ltd.,

- Chen M-T, Tseng Y-Y Efficacy of antimicrobial substances from Monascus metabolites on preservation of meat. In: 35. International Congress of Meat Science and Technology, Copenhagen (Denmark), 20–25 Aug 1989, 1989. SFI

- Choi SY, Yoon K-h, Lee JI, Mitchell RJ (2015) Violacein: properties and production of a versatile bacterial pigment. BioMed research international 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cragg GM, Newman DJ. Discovery and development of antineoplastic agents from natural sources. Cancer Invest. 1999;17(2):153–163. doi: 10.1080/07357909909011730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cserháti T (2006) Liquid chromatography of natural pigments and synthetic dyes, vol 71. Elsevier, [DOI] [PubMed]

- De Carvalho DD, Fabio TM, Costa, Duran N, Duran M. Cytotoxic activity of violacein in human colon cancer cells. Toxicol in Vitro. 2006;20(8):1514–1521. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davoli P, Weber RW. Carotenoid pigments from the red mirror yeast. Sporobolomyces roseus. Mycologist. 2002;16(3):102–108. [Google Scholar]

- Demain AL. Microbial production of primary metabolites. Naturwissenschaften. 1980;67(12):582–587. doi: 10.1007/BF00396537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duerre JA, Buckley PJ. Pigment production from tryptophan by an Achromobacter species. J Bacteriol. 1965;90(6):1686–1691. doi: 10.1128/jb.90.6.1686-1691.1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufossé L. Microbial production of food grade pigments. Food Technology and Biotechnology. 2006;44(3):313–323. [Google Scholar]

- Duran M, Ponezi AN, Faljoni-Alario A, Teixeira MF, Justo GZ, Duran N. Potential applications of violacein: a microbial pigment. Med Chem Res. 2012;21(7):1524–1532. doi: 10.1007/s00044-011-9654-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- S.editors B (2009) Microbial pigments. Biotechnology for agro-industrial residues, 8. Dodrdrecht. Springer

- El-Banna AAE-R, El-Razek AMA, El-Mahdy AR. Isolation, identification and screening of carotenoid-producing strains of Rhodotorula glutinis. Food Nutr Sci. 2012;3(05):627. doi: 10.4236/fns.2012.35086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fenical W. New pharmaceuticals from marine organisms. Trends Biotechnol. 1997;15(9):339–341. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(97)01081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira CV, Bos CL, Versteeg HH, Justo GZ, Durán N, Peppelenbosch MP. Molecular mechanism of violacein-mediated human leukemia cell death. Blood. 2004;104(5):1459–1464. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frandsen RJ, Nielsen NJ, Maolanon N, Sørensen JC, Olsson S, Nielsen J, Giese H. The biosynthetic pathway for aurofusarin in Fusarium graminearum reveals a close link between the naphthoquinones and naphthopyrones. Mol Microbiol. 2006;61(4):1069–1080. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galaup P, Sutthiwong N, Leclercq-Perlat MN, Valla A, Caro Y, Fouillaud M, Guérard F, Dufossé L. First isolation of Brevibacterium sp. pigments in the rind of an industrial red-smear-ripened soft cheese. Int J Dairy Technol. 2015;68(1):144–147. doi: 10.1111/1471-0307.12211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber NN. Prodigiosin-like pigments. CRC. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1975;3(4):469–485. doi: 10.3109/10408417509108758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber NN, Gauthier M. New prodigiosin-like pigment from Alteromonas rubra. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1979;37(6):1176–1179. doi: 10.1128/aem.37.6.1176-1179.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupte M, Kulkarni P, Ganguli B. Antifungal antibiotics. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2002;58(1):46. doi: 10.1007/s002530100822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyomarc’h F, Binet A, Dufossé L. Production of carotenoids by Brevibacterium linens: variation among strains, kinetic aspects and HPLC profiles. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2000;24(1):64–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.jim.2900761. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hendry GAF, Houghton J (1996) Natural food colorants. Springer Science & Business Media

- Herz S, Weber RW, Anke H, Mucci A, Davoli P. Intermediates in the oxidative pathway from torulene to torularhodin in the red yeasts Cystofilobasidium infirmominiatum and C. capitatum (Heterobasidiomycetes, Fungi) Phytochem. 2007;68(20):2503–2511. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobson DKWD. Green colorants. J Soc Dyers Colour. 1998;114:42–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-4408.1998.tb01944.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Houbraken J, Frisvad JC, Seifert K, Overy DP, Tuthill D, Valdez J, Samson R (2012) New penicillin-producing Penicillium species and an overview of section Chrysogena. Persoonia: Molecular Phylogeny and Evolution of Fungi 29:78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Howarth S, Dedman M. Pigmentation Variants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1964;88(2):273–278. doi: 10.1128/jb.88.2.273-278.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang P. Recombination and complementation of albino mutants in Neurospora. Genet. 1964;49(3):453. doi: 10.1093/genetics/49.3.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichiyama S, Shimokata K, Tsukamura M. Carotenoid pigments of genus Rhodococcus. Microbiol Immunol. 1989;33(6):503–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1989.tb01999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson EA. Phaffia rhodozyma: colorful odyssey. Int Microbiol. 2003;6(3):169–174. doi: 10.1007/s10123-003-0130-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson EA, Villa TG, Lewis MJ, Phaff HJ. Simple method for the isolation of astaxanthin from the basidiomycetous yeast Phaffia rhodozyma. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1978;35(6):1155–1159. doi: 10.1128/aem.35.6.1155-1159.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi V, Attri D, Bala A, Bhushan S. Microbial pigments. J Biotechnol. 2003;2(362):9. [Google Scholar]

- Katsube N, Iwashita K, Tsushida T, Yamaki K, Kobori M. Induction of apoptosis in cancer cells by bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus) and the anthocyanins. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51(1):68–75. doi: 10.1021/jf025781x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawauchi K, Shibutani K, Yagisawa H, Kamata H, Nakatsuji S, Anzai H, Yokoyama Y, Ikegami Y, Moriyama Y, Hirata H. A Possible Immunosuppressant, Cycloprodigiosin Hydrochloride, Obtained from Pseudoalteromonas denitrificans. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;237(3):543–547. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaneja R, Perez-Fons L, Fakhry S, Baccigalupi L, Steiger S, To E, Sandmann G, Dong T, Ricca E, Fraser P. Carotenoids found in Bacillus. J Applied Microbiol. 2010;108(6):1889–1902. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H-S, Hayashi M, Shibata Y, Wataya Y, Mitamura T, Horii T, Kawauchi K, Hirata H, Tsuboi S, Moriyama Y. Cycloprodigiosin hydrochloride obtained from Pseudoalteromonas denitrificans is a potent antimalarial agent. Biol Pharm Bull. 1999;22(5):532–534. doi: 10.1248/bpb.22.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Han S, Lee C, Lee K, Park S, Kim Y (2003) Use of prodigiosin for treating diabetes mellitus. Google Patents

- Kim C, Jung H, Kim JH, Shin CS. Effect of monascus pigment derivatives on the electrophoretic mobility of bacteria, and the cell adsorption and antibacterial activities of pigments. Colloids Surf B. 2006;47(2):153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Lee J, Park Y, Kim J, Jeong H, Oh TK, Kim B, Lee C. Biosynthesis of antibiotic prodiginines in the marine bacterium Hahella chejuensis KCTC 2396. J Appl Microbiol. 2007;102(4):937–944. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.03172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HW, Kim JB, Cho SM, Chung MN, Lee YM, Chu SM, Che JH, Kim SN, Kim SY, Cho YS. Anthocyanin changes in the Korean purple-fleshed sweet potato, Shinzami, as affected by steaming and baking. Food Chem. 2012;130(4):966–972. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.08.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kodach LL, Bos CL, Durán N, Peppelenbosch MP, Ferreira CV, Hardwick JC. Violacein synergistically increases 5-fluorouracil cytotoxicity, induces apoptosis and inhibits Akt-mediated signal transduction in human colorectal cancer cells. Carcinog. 2005;27(3):508–516. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodach LL, Bos CL, Durán N, Peppelenbosch MP, Ferreira CV, Hardwick JC. Violacein synergistically increases 5-fluorouracil cytotoxicity, induces apoptosis and inhibits Akt-mediated signal transduction in human colorectal cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27(3):508–516. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koes RE, Quattrocchio F, Mol JN. The flavonoid biosynthetic pathway in plants: function and evolution. BioEssays. 1994;16(2):123–132. doi: 10.1002/bies.950160209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kong J-M, Chia L-S, Goh N-K, Chia T-F, Brouillard R. Analysis and biological activities of anthocyanins. Phytochemistry. 2003;64(5):923–933. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(03)00438-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konuray G, Erginkaya Z (2015) Antimicrobial and antioxidant properties of pigments synthesized from microorganisms. The Battle Against Microbial Pathogens: Basic Science, Technological Advances and Educational Programs (A Méndez-Vilas, Ed) FORMATEX:27-33

- Konzen M, De Marco D, Cordova CA, Vieira TO, Antônio RV, Creczynski-Pasa TB. Antioxidant properties of violacein: possible relation on its biological function. Bioorg Med Chem. 2006;14(24):8307–8313. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korkina L. Phenylpropanoids as naturally occurring antioxidants: from plant defense to human health. Cell Mol Biol. 2007;53(1):15–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy K, Siva R, Senthil T (2002) Natural dye-yielding plants of Shervaroy Hills of Eastern Ghats. In: Proceedings of National Seminar on the Conservation of the Eastern Ghats, Environment Protection Training and Research Institute, Hyderabad, pp 24–26

- Lazzè MC, Savio M, Pizzala R, Cazzalini O, Perucca P, Scovassi AI, Stivala LA, Bianchi L. Anthocyanins induce cell cycle perturbations and apoptosis in different human cell lines. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25(8):1427–1433. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazaro J, Nitcheu J, Predicala RZ, Mangalindan GC, Nesslany F, Marzin D, Concepcion GP, Diquet B. Heptyl prodigiosin, a bacterial metabolite, is antimalarial in vivo and non-mutagenic in vitro. J Nat Toxins. 2002;11(4):367–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon LL, Machado GM, de Carvalho Paes LE, Grimaldi G. Antigenic differences of Leishmania amazonensis isolates causing diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1990;84(5):678–680. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(90)90144-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon LL, Machado G, Barral A, Carvalho-Paes LEd, Grimaldi Júnior G. Antigenic differences among Leishmania amazonensis isolates and their relationship with distinct clinical forms of the disease. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 1992;87(2):229–234. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02761992000200010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon L, Miranda C, De Souza A, Durán N. Antileishmanial activity of the violacein extracted from Chromobacterium violaceum. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001;48(3):449–450. doi: 10.1093/jac/48.3.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JW-H, Vederas JC. Drug discovery and natural products: end of an era or an endless frontier? Science. 2009;325(5937):161–165. doi: 10.1126/science.1168243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichstein HC, Van De Sand VF. The antibiotic activity of violacein, prodigiosin, and phthiocol. J Bacteriol. 1946;52(1):145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J, Yan XJ, Zheng L, Ma HH, Chen HM. Cytotoxicity and apoptosis induction of some selected marine bacteria metabolites. J Appl Microbiol. 2005;99(6):1373–1382. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe SW, Lin AW. Apoptosis in cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21(3):485–495. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik K, Tokkas J, Goyal S. Microbial pigments: a review. Int J Microbial Res Technol. 2012;1(4):361–365. [Google Scholar]

- Mapari SA, Nielsen KF, Larsen TO, Frisvad JC, Meyer AS, Thrane U. Exploring fungal biodiversity for the production of water-soluble pigments as potential natural food colorants. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2005;16(2):231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mapari SA, Meyer AS, Thrane U, Frisvad JC. Identification of potentially safe promising fungal cell factories for the production of polyketide natural food colorants using chemotaxonomic rationale. Microb Cell Fact. 2009;8(1):24. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-8-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin S, Giannone G, Andriantsitohaina R, Carmen Martinez M. Delphinidin, an active compound of red wine, inhibits endothelial cell apoptosis via nitric oxide pathway and regulation of calcium homeostasis. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;139(6):1095–1102. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matz C, Deines P, Boenigk J, Arndt H, Eberl L, Kjelleberg S, Jürgens K. Impact of violacein-producing bacteria on survival and feeding of bacterivorous nanoflagellates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70(3):1593–1599. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.3.1593-1599.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConkey DJ, Zhivotovsky B, Orrenius S. Apoptosis—molecular mechanisms and biomedical implications. Mol Aspects Med. 1996;17(1):1517396771–315376569110. doi: 10.1016/0098-2997(95)00006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellouli L, Ameur-Mehdi RB, Sioud S, Salem M, Bejar S. Isolation, purification and partial characterization of antibacterial activities produced by a newly isolated Streptomyces sp. US24 strain. Res Microbiol. 2003;154(5):345–352. doi: 10.1016/S0923-2508(03)00077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M, Yoneyama M, Soneda M. Phaffia, a new yeast genus in the Deuteromycotina (Blastomycetes) Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 1976;26(2):286–291. [Google Scholar]

- Mohana DC, Thippeswamy S, Abhishek RU. Antioxidant, antibacterial, and ultraviolet-protective properties of carotenoids isolated from Micrococcus spp. Radiation Prot Environ. 2013;36(4):168. doi: 10.4103/0972-0464.142394. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee G, Singh SK. Purification and characterization of a new red pigment from Monascus purpureus in submerged fermentation. Process Biochem. 2011;46(1):188–192. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2010.08.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nagpal N, Munjal N, Chatterjee S. Microbial pigments with health benefits-A mini review. Trends Biosci. 2011;4(2):157–160. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, Sawada T, Morita Y, Tamiya E. Isolation of a psychrotrophic bacterium from the organic residue of a water tank keeping rainbow trout and antibacterial effect of violet pigment produced from the strain. Biochem Eng J. 2002;12(1):79–86. doi: 10.1016/S1369-703X(02)00079-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nuijen B, Bouma M, Manada C, Jimeno J, Schellens JH, Bult A, Beijnen J. Pharmaceutical development of anticancer agents derived from marine sources. Anticancer Drugs. 2000;11(10):793–811. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200011000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palanichamy V, Hundet A, Mitra B, Reddy N (2011) Optimization of cultivation parameters for growth and pigment production by Streptomyces spp. isolated from marine sediment and rhizosphere soil. Int J Plant Animal Env Sci 1(3):158–170

- Pandey RC, Sainis Ramesh, Krishna B. Prodigiosins: a novel family of immunosuppressants with anti-cancer activity. Indian J Biochem Biophys. 2007;44(5):295–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parajó J, Santos V, Vázquez M. Optimization of carotenoid production by Phaffia rhodozyma cells grown on xylose. Process Biochem. 1998;33(2):181–187. doi: 10.1016/S0032-9592(97)00045-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- PDS Melo, Maria SS, Vidal BDC, Haun M, Durán N. Violacein cytotoxicity and induction of apoptosis in V79 cells. Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology-Animal. 2000;36(8):539–543. doi: 10.1290/1071-2690(2000)036<0539:VCAIOA>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radjasa OK, Limantara L, Sabdono A. Antibacterial activity of a pigment producing-bacterium associated with Halimeda sp. from eland-locked marine lake kakaban, Indonesia. J Coast Dev. 2009;12(2):100–104. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid M, Fakruddin M, Mazumdar RM, Kaniz F, Chowdhury M (2014) Anti-bacterial activity of pigments isolated from pigment-forming soil bacteria

- Richard C. Chromobacterium violaceum, opportunist pathogenic bacteria in tropical and subtropical regions. Bull Soc Pathol Exot (1990) 1992;86(3):169–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez C, Braña AF, Méndez C, Salas JA. Reevaluation of the violacein biosynthetic pathway and its relationship to indolocarbazole biosynthesis. ChemBioChem. 2006;7(8):1231–1240. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200600029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraiva VS, Marshall JC, Cools-Lartigue J, Jr Burnier MN. Cytotoxic effects of violacein in human uveal melanoma cell lines. Melanoma Res. 2004;14(5):421–424. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200410000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartsmann G, Brondani A, Berlinck R, Jimeno J. Marine organisms and other novel natural sources of new cancer drugs. Ann Oncol. 2000;11(3):235–243. doi: 10.1093/annonc/11.suppl_3.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartsmann G, da Rocha AB, Berlinck RG, Jimeno J. Marine organisms as a source of new anticancer agents. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2(4):221–225. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(00)00292-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirata A, Tsukamoto T, Yasui H, Hata T, Hayasaka S, Kojima A, Kato H (2000) Isolation of bacteria producing bluish-purple pigment and use for dyeing. JARQ (Japan)

- Singh M, Kumar A, Singh R, Pandey KD. Endophytic bacteria: a new source of bioactive compounds. 3. Biotech. 2017;7(5):315. doi: 10.1007/s13205-017-0942-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soliev AB, Hosokawa K, Enomoto K (2011) Bioactive pigments from marine bacteria: applications and physiological roles. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2011

- Sowbhagya H, Chitra V. Enzyme-assisted extraction of flavorings and colorants from plant materials. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2010;50(2):146–161. doi: 10.1080/10408390802248775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suresh M, Renugadevi B, Brammavidhya S, Iyapparaj P, Anantharaman P. Antibacterial activity of red pigment produced by halolactibacillus alkaliphilus MSRD1—an isolate from seaweed. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2015;176(1):185–195. doi: 10.1007/s12010-015-1566-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MW, Radax R, Steger D, Wagner M. Sponge-associated microorganisms: evolution, ecology, and biotechnological potential. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2007;71(2):295–347. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00040-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umadevi K, Krishnaveni M. Antibacterial activity of pigment produced from Micrococcus luteus KF532949. Int J Chem Anal Sci. 2013;4(3):149–152. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcas.2013.08.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ungureanu C, Ferdes M. Evaluation of antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of torularhodin. Adv Sci Lett. 2012;18(1):50–53. doi: 10.1166/asl.2012.4403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Venil CK, Lakshmanaperumalsamy P. An insightful overview on microbial pigment, prodigiosin. Electron J Biol. 2009;5(3):49–61. [Google Scholar]

- Venil CK, Zakaria ZA, Ahmad WA. Bacterial pigments and their applications. Process Biochem. 2013;48(7):1065–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2013.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Mazza G. Effects of anthocyanins and other phenolic compounds on the production of tumor necrosis factor α in LPS/IFN-γ-activated RAW 264.7 macrophages. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50(15):4183–4189. doi: 10.1021/jf011613d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav S, Manjunatha K, Ramachandra B, Suchitra N, Prabha R. Characterization of pigment producing rhodotorula from dairy environmental samples. Asian J Dairying & Foods Res. 2014;33(1):1–4. doi: 10.5958/j.0976-0563.33.1.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto C, Takemoto H, Kuno K, Yamamoto D, Tsubura A, Kamata K, Hirata H, Yamamoto A, Kano H, Seki T. Cycloprodigiosin hydrochloride, a new H+/Cl− symporter, induces apoptosis in human and rat hepatocellular cancer cell lines in vitro and inhibits the growth of hepatocellular carcinoma xenografts in nude mice. Hepatol. 1999;30(4):894–902. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youdim KA, McDonald J, Kalt W, Joseph JA. Potential role of dietary flavonoids in reducing microvascular endothelium vulnerability to oxidative and inflammatory insults. J Nutr Biochem. 2002;13(5):282–288. doi: 10.1016/S0955-2863(01)00221-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Zhan J, Su K, Zhang Y. A kind of potential food additive produced by Streptomyces coelicolor: characteristics of blue pigment and identification of a novel compound, λ-actinorhodin. Food Chem. 2006;95(2):186–192. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.12.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]