Abstract

Genome-wide association studies have identified numerous variants associated with lipid levels; yet, the majority are located in non-coding regions with unclear mechanisms. In the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Family Study (IRASFS), heritability estimates suggest a strong genetic basis: low-density lipoprotein (LDL, h2 = 0.50), high-density lipoprotein (HDL, h2 = 0.57), total cholesterol (TC, h2 = 0.53), and triglyceride (TG, h2 = 0.42) levels. Exome sequencing of 1,205 Mexican Americans (90 pedigrees) from the IRASFS identified 548,889 variants and association and linkage analyses with lipid levels were performed. One genome-wide significant signal was detected in APOA5 with TG (rs651821, PTG = 3.67 × 10−10, LODTG = 2.36, MAF = 14.2%). In addition, two correlated SNPs (r2 = 1.0) rs189547099 (PTG = 6.31 × 10−08, LODTG = 3.13, MAF = 0.50%) and chr4:157997598 (PTG = 6.31 × 10−08, LODTG = 3.13, MAF = 0.50%) reached exome-wide significance (P < 9.11 × 10−08). rs189547099 is an intronic SNP in FNIP2 and SNP chr4:157997598 is intronic in GLRB. Linkage analysis revealed 46 SNPs with a LOD > 3 with the strongest signal at rs1141070 (LODLDL = 4.30, PLDL = 0.33, MAF = 21.6%) in DFFB. A total of 53 nominally associated variants (P < 5.00 × 10−05, MAF ≥ 1.0%) were selected for replication in six Mexican-American cohorts (N = 3,280). The strongest signal observed was a synonymous variant (rs1160983, PLDL = 4.44 × 10−17, MAF = 2.7%) in TOMM40. Beyond primary findings, previously reported lipid loci were fine-mapped using exome sequencing in IRASFS. These results support that exome sequencing complements and extends insights into the genetics of lipid levels.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death worldwide1. In the United States, CVD accounts for more deaths than any other major cause and, on average, 2,200 Americans die of CVD each day2. While the exact mechanism of disease remains unclear, lipid concentrations are well-accepted as a major risk factor as well as clinical indicators for CVD. Genetic studies have suggested a strong heritability for circulating lipid levels, i.e. total cholesterol (TC), LDL cholesterol (LDL), HDL cholesterol (HDL), and triglycerides (TG). Based on a European twin-pairs study, it is estimated that circulating lipid heritability ranges from 0.58 to 0.66 (h2HDL = 0.61, h2LDL = 0.59, h2TC = 0.58, h2TG = 0.66)3.

Given the public health relevance as well as the strong genetic component, numerous genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have been performed to investigate the genetic architecture of circulating lipid levels. The most recent Global Lipid Genetics Consortium (GLGC) analyzed 188,577 individuals from four ethnicities (Europeans, East Asians, South Asians, and Africans) and identified 157 loci associated with plasma lipid traits4. While well-powered, these efforts have largely overlooked the fastest growing US minority population, Hispanic Americans. Compared to non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics suffer an even higher risk for CVD, i.e. 32.1% versus 23.8%5,6. Until now, the largest lipid GWAS in Hispanics was performed by Below et al. in 2015 with 4,383 Mexican ancestry individuals. However, all genome-wide significant regions identified in the Mexican meta-analysis were previously identified4,7–9.

GWAS were designed with a focus on common variants, partly supported by the “common disease, common variant” hypothesis10. However, despite the large number of genetic signals identified by GWAS, over 80% fall outside of protein coding regions, which complicates causal inference10. Among genes with evidence of association, only a small proportion of the variance is explained, providing limited information for disease risk prediction4,11. Sequencing of the exome, rather than the entire human genome, has been shown to be an efficient strategy to search for novel variants with a clear biological mechanism12. Previous exome sequencing studies have identified multiple rare variants associated with CVD in non-Hispanic populations13,14.

To search for functional coding variants regulating circulating lipid levels in a Mexican-ancestry population, whole exome sequencing was performed in 1,205 Mexican Americans from the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Family Study (IRASFS). Association and family-based linkage analyses were performed for 548,889 variants. We hypothesized that a family cohort would have increased power to detect rare variants due to their transmission in multigenerational pedigrees. With the complimentary approaches of linkage and association, exome sequencing has the potential to identify ethnic-specific variants regulating lipid levels.

Results

A total of 1,205 individuals were included in association and linkage analyses. Characteristics of the study individuals are shown in Table 1. Overall, individuals were predominantly female (59%) and were overweight with an average BMI of 28.9 kg/m2. Since the recruitment was based on family size rather than diagnosis, e.g. CVD was not required for participation, the participants were metabolically normal, with an average HDL (43.61 mg/dl), LDL (109.41 mg/dl), TC (178.06 mg/dl), and TG (124.80 mg/dl) within desirable or near-desirable ranges15. According to the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP)15, 183 individuals (15%) within the study had undesirable high TG levels (TG > 150 mg/dl), 121 (10%) individuals had an LDL level greater than 160 mg/dl, 521 (43%) individuals had an HDL level less than 40 mg/dl, and 290 (24%) individuals had a TC level greater than 200 mg/dl.

Table 1.

Demographic information of the study individuals.

| Discovery | Replication | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRASFS | IRAS | TRIPOD | BetaGene | HTN-IR | MACAD | NIDDM-Athero | |

| n | 1205 | 181 | 125 | 1218 | 763 | 749 | 244 |

| Female (%) | 58.5 | 41.1 | 100.0 | 27.5 | 41.1 | 42.6 | 38.9 |

| Age (years)b | 42.7 ± 14.5 | 54.1 ± 8.2 | 34.9 ± 6.4 | 34.7 ± 7.9 | 39.3 ± 15.1 | 34.7 ± 9.1 | 38.1 ± 14.9 |

| Body Mass Index (BMI; kg/m2) | 28.9 ± 6.2 | 28.2 ± 5.1 | 30.8 ± 5.6 | 29.6 ± 6.1 | 29.3 ± 5.7 | 29.0 ± 5.2 | 29.1 ± 6.3 |

| High-density Lipoprotein (HDL; mg/dl) | 43.61 ± 12.86 | 43.18 ± 14.63 | 37.39 ± 9.52 | 46.89 ± 11.08 | 48.13 ± 13.24 | 46.14 ± 12.12 | 47.5 ± 11.7 |

| Low-density Lipoprotein (LDL; mg/dl) | 109.41 ± 31.04 | 140.04 ± 36.75 | 109.01 ± 27.30 | 102.80 ± 28.65 | 106.03 ± 31.38 | 108.23 ± 31.3 | 106.63 ± 32.01 |

| Total Cholesterol (TC; mg/dl) | 178.06 ± 37.45 | 210.90 ± 43.74 | 173.15 ± 32.59 | 172.52 ± 33.25 | 179.01 ± 35.41 | 180.53 ± 36.43 | 181.47 ± 39.23 |

| Triglycerides (TG; mg/dl) | 124.80 ± 84.00 | 157.24 ± 99.21 | 133.79 ± 78.91 | 114.12 ± 90.27 | 124.23 ± 78.96 | 137.25 ± 102.82 | 145.19 ± 166 |

Heritability analysis in IRASFS suggested a strong genetic component for lipid levels. HDL had the strongest heritability (h2HDL = 0.57) with 17.2% of the variance explained by covariates (age, sex, center, BMI; P = 5.87 × 10−26), the heritability of TC was 0.53 with 10.3% of the variance explained by covariates (P = 3.12 × 10−23), the heritability of LDL was 0.50 with 7.3% of the variance explained by covariates (P = 1.22 × 10−21), and TG had the lowest heritability (h2TG = 0.42) with 15.9% of the variance explained by covariates (P = 5.37 × 10−14) (Table S1).

From exome sequencing data, a total of 548,889 variants were successfully analyzed for association and linkage. Among them, 30.0% (164,591) were extremely rare variants with only one or two observations and 82.5% (452,807) were low frequency variants as defined by a MAF < 5% (Figure S1); 6.8% (N = 37,157) of the variants were insertions/deletions; 33.1% (N = 182,020) and 15% (N = 83,874) of the variants marked a non-synonymous and synonymous amino acid change in coding genes, respectively.

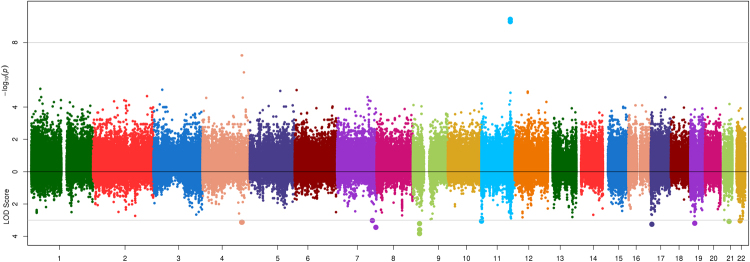

Association and linkage results are shown in Figs 1–4. The strongest evidence of association attaining genome-wide significance (P < 5.00 × 10−08) was observed at the apolipoprotein A-V gene (APOA5) on chromosome 11 with two highly correlated SNPs (r2 = 0.92) rs651821 (P = 3.67 × 10−10, LOD = 2.36, MAF = 14%) and rs2072560 (P = 5.14 × 10−10, LOD = 2.05, MAF = 13%) and TG (Fig. 4; Table 2). Conditional analysis on one variant was able to abolish the signal limiting the ability to statistically implicate a functional variant. In addition, both SNPs were also nominally associated with HDL (Prs651821 = 2.63 × 10−3; Prs2072560 = 9.42 × 10−3), while no signal was detected for LDL (P > 0.90) or TC (P > 0.18). On average, individuals had 23% more TG for each risk allele carried at rs651821 (TT: 117.59 mg/dl, TC: 142.62 mg/dl, CC: 174.41 mg/dl). Nominally associated and linked signals are provided in Table S2.

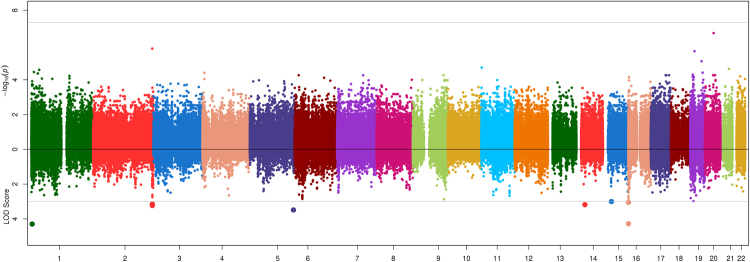

Figure 2.

Opposed plots for association and linkage analysis of LDL. Association results are plotted on the positive y-axis. The line at –log10(PVAL) = 7.30 represents genome-wide significance (P = 5.00 × 10−08). The linkage results are plotted on the negative y-axis. The line at LOD = 3 represents a significant linkage signal.

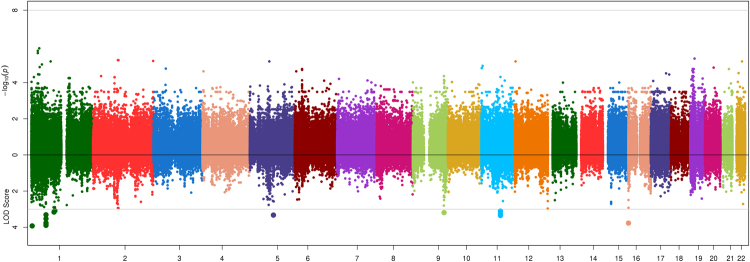

Figure 3.

Opposed plots for association and linkage analysis of TC. Association results are plotted on the positive y-axis. The line at –log10(PVAL) = 7.30 represents genome-wide significance (P = 5.00 × 10−08). The linkage results are plotted on the negative y-axis. The line at LOD = 3 represents a significant linkage signal.

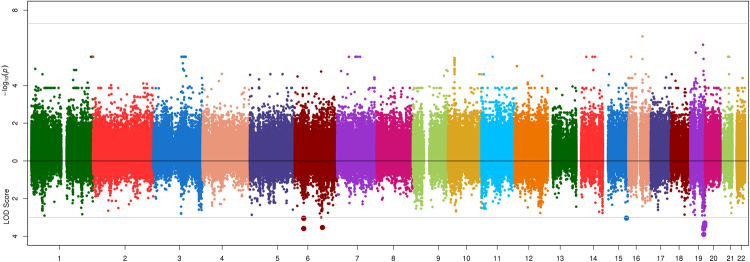

Figure 1.

Opposed plots for association and linkage analysis of HDL. Association results are plotted on the positive y-axis. The line at –log10(PVAL) = 7.30 represents genome-wide significance (P = 5.00 × 10−08). The linkage results are plotted on the negative y-axis. The line at LOD = 3 represents a significant linkage signal.

Figure 4.

Opposed plots for association and linkage analysis of TG. Association results are plotted on the positive y-axis. The line at –log10(PVAL) = 7.30 represents genome-wide significance (P = 5.00 × 10−08). The linkage results are plotted on the negative y-axis. The line at LOD = 3 represents a significant linkage signal.

Table 2.

Top association (P < 9.11 × 10−08) and linkage signals (LOD > 4).

| SNP | Chr:Pos (hg19) | Gene | Annotation | Allelesa | RAFb | PHDL | LODHDL | PLDL | LOGLDL | PTC | LODTC | PTG | LODTG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs1141070 | 1:3786189 | DFFB | coding-synon | A/G | 0.22 | 0.98 | 0.01 | 0.33 | 4.30 | 0.74 | 3.93 | 0.87 | 0.27 |

| chr4:157997598 | 4:157997598 | GLRB | intron | T/C | 0.0050 | 2.88E-04 | 1.87 | 0.71 | 0 | 0.24 | 0 | 6.31E-08 | 3.13 |

| rs189547099 | 4:159814881 | C4orf45 | intron | C/G | 0.0050 | 2.88E-04 | 1.87 | 0.71 | 0 | 0.24 | 0 | 6.31E-08 | 3.13 |

| rs2072560 | 11:116661826 | APOA5 | intron | T/C | 0.13 | 2.03E-03 | 0.32 | 0.87 | 0 | 0.014 | 0.010 | 5.14E-10 | 2.06 |

| rs651821 | 11:116662579 | APOA5 | intron | C/T | 0.14 | 8.93E-04 | 0.30 | 0.99 | 0 | 0.018 | 0 | 3.67E-10 | 2.36 |

| rs11648905 | 16:425298 | TMEM8A | intron | T/G | 0.41 | 0.74 | 0 | 0.78 | 4.28 | 0.84 | 3.77 | 0.18 | 0.82 |

aReference (minor)/Other allele; bReference allele frequency based on the entire population.

Additional evidence of association which attained exome-wide significance (P < 9.11 × 10−08; based on a conservative Bonferroni correction for 548,889 variants) included two correlated SNPs (r2 = 1.0) on chromosome 4: rs189547099 (PTG = 6.31 × 10−08, LODTG = 3.13, MAF = 0.5%) and chr4:157997598 (PTG = 6.31 × 10−08, LODTG = 3.13, MAF = 0.5%) (Table 2). Notably, these variants were both significantly associated and linked with TG. SNP rs189547099 is an intronic SNP located in the folliculin interacting protein 2 gene (FNIP2) and the chromosome 4 open reading frame 45 (C4orf25). SNP chr4:157997598 is located 1,817 kb upstream of SNP rs189547099 in the first intron of the glycine receptor beta gene (GLRB). On average, risk allele (T) heterozygous carriers for chr4:157997598 had 2.9 times TG compared to non-carriers (CC: 124 mg/dl vs. TC: 358 mg/dl). No risk allele homozygotes were found. Burden testing failed to identify additional genes significantly associated with lipid phenotypes after correction for the number of test performed, i.e. P < 7.23 × 10−06, 0.05/139,173; Table S3.

Two-point linkage analysis was performed for 548,889 variants. Of these, two SNPs had a LOD score greater than 4 (Table 2), 46 SNPs had a LOD score greater than 3 (Table S4). Among these, 14 variants were significantly linked (LOD > 3) with TC, 13 variants were significantly linked with HDL, 13 variants were significantly linked with TG, and 8 variants were significantly linked with LDL with two variants overlapping between TC and LDL. The strongest linkage signal was observed at SNP rs1141070 (LODLDL = 4.30 LODTC = 3.93, MAF = 22%) with LDL and TC levels. rs1141070 is located in exon 5 of the DNA fragmentation factor gene (DFFB) on chromosome 1 and marks a synonymous amino acid substitution. In addition, SNP rs11648905 (LODLDL = 4.28, LODTC = 3.77, MAF = 41%) was strongly linked with LDL and TC levels. This variant is an intronic SNP located between exon 7 and 8 of the transmembrane protein 8 A gene (TMEM8A). No significant association signals were observed for the two linked signals: rs1141070, PLDL = 0.33, PTC = 0.74; rs11648905, PLDL = 0.78, PTC = 0.84 (Table 2).

Meta-analysis

Meta-analysis with six additional independent cohorts was computed for the 53 selected SNPs. Overall, six variants reached genome-wide significance after meta-analysis (Table 3). The strongest signal was observed at rs1160983 (PLDL = 4.44 × 10−17, MAF = 2.7%) with LDL. rs1160983 is a synonymous coding variant in the translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 40 gene (TOMM40). The two APOA5 variants, which attained genome-wide significance in IRASFS, were also successfully replicated (meta-analysis p-values: rs2072560, PTG = 5.67 × 10−16; rs651821, PTG = 2.66 × 10−15) with a consistent direction of effect across all cohorts. In addition, strong meta-analysis signals were detected for APOA1 (rs2070665, PTG = 7.03 × 10−09) and CETP (rs1532625, PHDL = 7.72 × 10−14, rs11076176, PHDL = 2.15 × 10−08) with TG and HDL, respectively. SNP rs72685601 was selected as the proxy SNP (r2 = 0.59) for the two variants that reached exome-wide significance (chr4:157997598, rs189547099). It was nominally associated with TG (PTG = 3.69 × 10−03) with consistent direction of effect across six of the seven cohorts. A complete list of meta-analysis results can be found in Table S5.

Table 3.

Top association signals (P < 5 × 10−8) from meta-analysis.

| SNP | Chr:Pos (hg19) | RAFa | Trait | Gene | Annotation | IRASFS | Meta-analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | P | N | P | ||||||

| rs2072560 | 11:116661826 | 0.13 | TG | APOA5 | intron | 1205 | 5.14E-10 | 4241 | 5.67E-16 |

| rs651821 | 11:116662579 | 0.14 | TG | APOA5 | intron | 1205 | 3.67E-10 | 4241 | 2.66E-15 |

| rs2070665 | 11:116707684 | 0.17 | TG | APOA1 | intron | 1205 | 4.10E-05 | 4241 | 7.03E-09 |

| rs1532625 | 16:57005301 | 0.38 | HDL | CETP | intron | 1205 | 2.46E-07 | 4235 | 7.72E-14 |

| rs11076176 | 16:57007446 | 0.28 | HDL | CETP | intron | 1205 | 3.87E-06 | 4235 | 2.15E-08 |

| rs1160983 | 19:45397229 | 0.027 | LDL | TOMM40 | synonymous | 1205 | 8.61E-06 | 4177 | 4.44E-17 |

aReference allele frequency based on the IRASFS cohort.

Previously identified lipid loci

Fine-mapping of the previously identified 157 loci +/−100 kb resulted in a total of 14,232 exome sequencing variants which were analyzed for association and linkage in IRASFS. In addition, conditional analyses based on the locus-specific GLGC index SNP were performed (Table S6). For association, 1,231 of the variants were identified with a P-value less than 0.05 with at least one of the reported lipid traits. Among the 1,231 significant variants, 646 remained to be significant (P < 0.05) after conditional analysis based on the locus-specific index SNP. The strongest association signal was observed at rs651821 (PTG = 3.67 × 10−10, LODTG = 2.36) in APOA5. After conditioning on SNP rs964184, it remained nominally associated and linked with TG (PTG|rs964184 = 1.76 × 10−04, LODTG|rs964184 = 0.99). In addition, SNP rs1532625 also survived the stringent Bonferroni correction (P < 3.51 × 10−06 for 14,232 variants): PHDL = 2.46 × 10−07, LODHDL = 1.42. This SNP is an intronic variant located in the cholesteryl ester transfer protein gene (CETP). However, conditional analysis with the index SNP rs3764261 totally abolished the signal (PHDL|rs3764261 = 0.61, LODHDL|rs3764261 = 0.02). For linkage analysis, 14 and 127 SNPs reached a LOD score greater than two and one, respectively, for at least one reported lipid trait. Among them, one (rs1134760, LODHDL|rs16942887 = 2.46) and 28 (LOD > 1) remained to be linked after conditional analysis, respectively.

Discussion

An individual’s lipid profile represents a well-accepted major risk factor and clinical indicator of CVD. In this study, heritability estimates for four lipid phenotypes were reported in Mexican Americans from IRASFS and demonstrated a strong genetic component. Subsequently, exome-wide association analysis was performed using exome sequencing data derived from 1,205 Mexican Americans from IRASFS. Multiple significant association signals were identified and top signals were evaluated in six additional independent cohorts (n = 3,280). As a complementary approach to association, linkage analysis was performed to identify rare variant signals. In addition, 157 previously identified lipid loci were fine-mapped using exome sequencing data in IRASFS.

Strong association and suggestive linkage signals were observed with two SNPs in APOA5: rs651821 (PTG = 3.67 × 10−10, LODTG = 2.36, MAF = 14%) and rs2072560 (PTG = 5.14 × 10−10, LODTG = 2.05, MAF = 13%). APOA5 encodes an apoliporotein that plays an important role in regulating plasma triglyceride levels, which is a strong risk factor for CVD16. This gene is located within the apolipoprotein gene cluster on chromosome 11q23.3, which contains multiple lipid-related genes including APOA1, APOA3, APOA4, APOA5, and PCSK7. Multiple strong association signals have been identified in the region with HDL, TG, and TC4,9,17. In 2015, Do et al.14 described a large exome sequencing study in 9,793 European and African Americans and identified strong associations between APOA5 functional variants and myocardial infraction (MI). A recent Hispanic GWAS of lipid phenotypes identified SNP rs964184, 359 bases downstream of zinc finger protein 259 (ZNF259) and 11 kb downstream of APOA5, as significantly associated with TG7. In addition, Parra et al. presented robust association for rs964184 and no comparable signals were identified in the 5’ UTR for APOA518. In IRASFS, SNP rs964184 was also associated with TG (P = 4.79 × 10−07). However, including SNP rs964184 as a covariant failed to completely abolish the genetic signal of rs651821 (Pbefore = 3.67 × 10−10, Pafter = 1.76 × 10−−04), suggesting that the two signals were likely independent (r2 = 0.37) (Figure S2).

In IRASFS, two common variants (rs651821, rs2072560) within APOA5 were identified with strong association signals with TG in a Mexican-American family cohort. While SNP rs651821 and rs2072560 have been previously identified to be strongly associated with TG in multiple ethnicities (Europeans, East Asians, and North Africans)19–23, this is the first reported evidence in a Mexican-ancestry population. SNP rs651821 is a 5′-UTR variant that is three bases upstream of the coding exon. Worth mentioning, rs651821 is also located in the binding site of transcription factor POLR2A as suggested in HepG2 cells by ENCODE24. Previous expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) studies revealed associations between rs651821 and transgelin (TAGLN) gene expression levels25 yet no APOA5 expression regulation effect was found. SNP rs2072560 is located intronically between exons 3 and 4 of APOA5. Interestingly, rs2072560 is also a missense variant of an alternative transcript of APOA5 (NM_001166598) which contains two exons. This variant marks a glutamic acid to glycine amino acid change (E66G) in exon 2 (Figure S5). To further explore the potential function of the alternative transcript, four ENCODE primary hepatocyte RNA sequencing experiments were analyzed and plotted using the UCSC genome browser24,26. However, no RNA sequencing evidence was found to support existence or function of the alternative transcript (Figure S5). Taken together, strong association, linkage, and replication signals were identified for the two APOA5 SNPs with TG in Mexican Americans. While not enough biological evidence was found to support their causality, the results refined the scope of the APOA5 association signals and provided information for future efforts to locate the causal variant in the region.

While not attaining strict genome-wide significance, two correlated SNPs (r2 = 1.0) rs189547099 (PTG = 6.31 × 10−08, LODTG = 3.13, MAF = 0.5%) and chr4:157997598 (PTG = 6.31 × 10−08, LODTG = 3.13, MAF = 0.5%) were detected with exome-wide significance. These are two rare SNPs with 12 heterozygous and no homozygous carriers. SNP rs189547099 is an intronic variant for both the chromosome 4 open reading frame 45 gene (C4orf45) and folliculin interacting protein 2 gene (FNIP2). C4orf45 is an uncharacterized gene with unknown biological function. GTEx27 has detected that C4orf45 is strongly expressed in testis, yet there was almost no expression in other tissues. FNIP2 is a tumor suppressor gene that has been shown to be involved in regulating the apoptosis signaling pathway in tumors and is responsible for cellular metabolism and nutrient sensing28,29. SNP chr4:157997598 is an intronic variant in the glycine receptor beta gene (GLRB). This gene encodes the beta subunit of the glycine receptor and has been shown to function as a neurotransmitter-gated ion channel. Mutations in this gene have been shown to cause startle disease30,31. Interestingly, SNP chr4:157997598 is located in a CpG island and modifies the binding consensus sequence for a transcription factor zinc finger protein 263 (ZNF263) (Figure S6). Although no biological mechanism was found between GLRB and lipid metabolism, it is possible that SNP chr4:157997598 regulates TG levels through ZNF263.

Among the 53 variants identified for replication, synonymous SNP rs1160983 in exon 5 of the translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 40 gene (TOMM40) exhibited the strongest association signal after replication and meta-analysis with six independent cohorts (PLDL = 4.44 × 10−17, MAF = 2.7%). Before meta-analysis, this variant was nominally associated in IRASFS (PLDL = 8.61 × 10−06). TOMM40 has been shown to be the forming subunit of the translocase of the mitochondrial outer membrane complex and is essential for the import of protein precursors into mitochondria32. Genetic studies have identified two adjacent genes (APOE and TOMM40) in this region to be highly associated with circulating lipid levels4,33. After reviewing previously identified APOE variants, SNP rs7412 has the highest LD with rs1160983 (r2 = 0.49, D′ = 0.94). In IRASFS, rs7412 was nominally associated with LDL (PLDL = 6.61 × 10−06). Interestingly, after adjusting for the APOE variant (rs7412), rs1160983 remained nominally significant (P = 9.10 × 10−03) with LDL. This suggests that the known APOE signals do not fully explain the rs1160983 signal in TOMM40. It is possible that TOMM40 may directly contribute to the regulation of LDL levels or SNP rs1160983 may influence APOE expression.

An interesting observation from this study is the lack of overlap between the majority of linkage and association signals, even with exome sequencing data. One explanation is that association and linkage capture different mechanisms of phenotypic contributions. Association analysis detects signals that statistically associate with phenotypic variability either directly or through linkage disequilibrium (LD) and thus targets more proximal effects. Linkage detects the co-segregation of an allele with the phenotype in families and therefore can detect long-range effects due to limited recombination events across successive generations. Therefore, each approach has its advantages and limitations. For example, association analysis has gained much success in common variant analysis while often suffering from reduced power to detect rare variants, e.g. statistical power is largely affected by inadequate sample size and limited LD with proximal common variants. In contrast, linkage analysis performance is largely dependent on family structures as well as the number of segregation events, e.g. when family structures are incomplete or allele segregation information is incomplete (only two generations or the parental generation allele information is missing), linkage analysis performance is largely dampened. On the other hand, rare variants (in populations) that are missed by association can be relatively common in a given family with segregation across multiple generations. In this scenario, linkage has increased power over association. Taken together, both association and linkage analysis are valuable approaches for analyzing sequencing data in genetic studies, providing potentially independent information.

Despite multiple strong signals identified, study limitations exist. First, the modest sample size in IRASFS (n = 1,205) limits the power for the association analysis of rare variants, especially given the fact that 82% of the variants analyzed had a MAF < 5%. As a complementary approach, linkage analysis in 90 pedigrees was performed and identified signals that were likely missed by association. Unfortunately, linkage analysis was unavailable in the replication cohorts, and therefore meta-analysis of linkage signals was not performed. Dyslipidemia was not required for participation in IRASFS, thus the majority of individuals were metabolically normal, potentially providing limited enrichment of genetic risk alleles. Third, exome sequencing was not available in replication cohorts, and therefore replication was limited to GWAS imputed or proxy variants only. This approach modestly limited the number of SNPs for replication. Also, while all cohorts were of Mexican ancestry, different ascertainment criteria were used. For example, BetaGene recruited participants at high risk of gestational diabetes while HTN-IR recruited participants at high risk of hypertension. This differs from IRASFS which is a population-based study recruited for large family size.

In summary, exome-wide association and linkage analyses were performed using exome sequencing data in 1,205 Mexican Americans from IRASFS. Multiple signals were detected with circulating lipid levels and top signals were analyzed in six additional independent cohorts for replication. Our results suggested multiple lipid genetic signals in APOA5, TOMM40, and GLRB/C4orf45, fine-mapped known lipid genes with exome sequencing data in IRASFS, and explored a combined approach of association and linkage analyzing sequencing data. These results confirm that exome sequencing is a powerful tool to screen for functional genetic variants in the population.

Methods

Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Family Study (IRASFS)

The study design, recruitment, and phenotyping for the IRASFS has been previously described34. In brief, the IRASFS was designed to investigate the genetic and environmental basis of insulin resistance and adiposity. Mexican Americans included in this cohort (n = 1,205 individuals, 90 pedigrees) were recruited from clinical centers in San Antonio, TX and San Luis Valley, CO. Recruitment was based on reported family size and not on health status. Phenotype acquisition and variable calculations have been previously described34,35. In brief, TC, TG, and HDL were measured from fasting plasma with standards and LDL was calculated using the Friedewald formula. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of each participating clinical and analysis site and all participants provided their written informed consent. All methods in this study were carried out in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Exome Sequencing

Exome sequencing was performed at Texas Biomedical Research Institute using the Illumina Nextera Exome Enrichment System in conjunction with the Illumina HiSeq 2500 sequencer. All sequence reads passed through the Illumina Data Analysis Pipeline, and those from samples passing QC criteria were mapped to the human genome reference sequence (hg19). A detailed description of the sequencing platform and analysis pipeline has been published36. Of note, multi-sample recalibration was performed prior to variant calling. The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Statistical Analysis

To ensure normality, high density lipoprotein (HDL), total cholesterol (TC), and triglycerides (TG) were natural log-transformed; low density lipoprotein (LDL) was square root-transformed. While lipid medications were carefully evaluated, the majority of the participants in IRASFS were metabolically healthy with a lipid medication rate of 3.9%. Therefore, only a single regression model was performed without accounting for lipid medication status. Heritability of lipid levels was estimated using Sequential Oligogenic Linkage Analysis Routines (SOLAR)37 adjusting for age, sex, body mass index (BMI), and recruitment center. Variants with Mendelian inconsistencies were removed (n = 4,024), resulting in a final number of 548,889 variants38. Each variant was coded to an additive model based on the minor allele (reference allele). Genetic models of association were calculated adjusting for age, sex, BMI, recruitment center, and admixture estimates. Admixture estimates were calculated as described previously39 using maximum likelihood estimation of individual ancestries as implemented in ADMIXTURE40. Tests of association between individual variants and quantitative traits were computed using the Wald test from the variance component model implemented in SOLAR. Burden tests were computed using famSKAT41. Gene units were defined using the UCSC gene definition file from NCBI genome build 37 (hg19) whereby each alternatively spliced transcript is included for a total of 39,173 genes. For family-based linkage analysis, variant-specific identity-by-descent (IBD) probabilities were computed using the Monte Carlo method implemented in SOLAR42. Two-point linkage was performed using the variance components method implemented in SOLAR, with adjustment of age, gender, BMI, and recruitment center42. Variant annotation was performed using ANNOVAR43.

Replication and Meta-analysis

Six cohorts participating in the Genetics Underlying Diabetes in Hispanics (GUARDIAN) Consortium44 provided in silico replication data: the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study (IRAS45), BetaGene46–49, the Troglitazone in Prevention of Diabetes Study (TRIPOD50,51), the Hypertension-Insulin Resistance Family Study (HTN-IR52,53), the Mexican-American Coronary Artery Disease Study (MACAD54–56) and the NIDDM-Atherosclerosis Study (NIDDM-Athero57). All study protocols were approved by the local institutional review committees and all participants gave their informed consent. GWAS genotyping was supported through the GUARDIAN Consortium44 using the Illumina OmniExpress array (Illumina Inc.; San Diego, CA, USA) and imputation was performed centrally using IMPUTE258 and the 1000 Genomes phase l integrated reference panel (March 2012). Variants included in analysis had confidence scores > 0.90 and information scores > 0.50. A detailed description of quality control has been described previously39.

A total of 56 nominally associated SNPs (P < 5.00 × 10−05) with minor allele frequency (MAF) ≥ 1.0% as well as two rare SNPs that reached exome-wide significance (P < 9.11 × 10−08, MAF < 1.0%) were selected for replication in the GUARDIAN Consortium. Meta-analysis was performed among IRASFS (nmax = 1,205), IRAS (nmax = 181), BetaGene (nmax = 1,218), TRIPOD (nmax = 125), HTN-IR (nmax = 763), MACAD (nmax = 749), and NIDDM-Athero (nmax = 244) using the 1000 Genomes imputation dataset. Overall, 49 SNPs were directly tagged in replication cohorts and four SNPs were tagged by a proxy SNP (r2 > 0.6). However, no available proxies were found for the remaining five SNPs, which were excluded, resulting in a total of 53 SNPs in the meta-analysis. The meta-analysis was computed using METAL (http://csg.sph.umich.edu/abecasis/metal). Considering the differential study designs, a weighted meta-analysis of the p-values and samples sizes accounting for direction of effect was performed.

Previously identified signals

Previously identified lipid loci (N = 157) from the recent GLGC4 were extracted and all exome sequencing variants within ± 100 kb of the reported index SNPs were selected for fine-mapping. Conditional association and linkage analyses were performed with the GLGC index SNP as an adjusting covariate.

ENCODE RNA sequencing data

Four human primary hepatocytes RNA sequencing results were plotted using the UCSC genome browser24,26. The four liver biopsy samples included were derived from four European individuals: GSM2072386 (20-week female), GSM2072387 (22-week male), GSM2072372 (32-year male), and GSM2072373 (6-year female).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This research was jointly supported by HG007112 from the national Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) and DK097524 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). Computational resources were provided, in part, by the Wake Forest School of Medicine Center for Public Health Genomics. The authors would like to acknowledge the members of the GUARDIAN Consortium with research supported by DK085175 from NIDDK and from the following grants: IRAS Classic (HL047887, HL047889, HL047890, and HL47902), IRAS Family Study (HL060944 and HL061019), BetaGene (DK061628), MACAD (HL088457), HTN-IR (HL069794), and NIDDM (HL055798). The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the studies for their valuable contributions. The provision of genotyping data was supported in part by UL1TR000124 (CTSI), DK063491 (DRC), DK081350, HG007112 and DK087914.

Author Contributions

C.G. researched the data and wrote the manuscript; K.L.T. and N.D.P. researched the data and reviewed/edited the manuscript; L.M.D., K.D.T., N.W., X.G., J.L., J.C. performed analysis; J.I.R., R.M.W., J.B., C.D.L., D.W.B. contributed to discussion and reviewed/edited the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-23727-2.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Libby P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature. 2002;420:868–874. doi: 10.1038/nature01323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mozaffarian D, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2016 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133:e38–60. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knoblauch H, et al. Heritability analysis of lipids and three gene loci in twins link the macrophage scavenger receptor to HDL cholesterol concentrations. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:2054–2060. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.17.10.2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Willer CJ, et al. Discovery and refinement of loci associated with lipid levels. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1274–1283. doi: 10.1038/ng.2797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Go AS, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2013 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127:e6–e245. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31828124ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.CDC. Deaths, percent of total deaths, and death rates for the 15 leading causes of death in 10-year age groups, by race and sex: United States, 2013. (2013).

- 7.Below JE, et al. Meta-analysis of lipid-traits in Hispanics identifies novel loci, population-specific effects, and tissue-specific enrichment of eQTLs. Sci Rep. 2016;6:19429. doi: 10.1038/srep19429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Willer CJ, et al. Newly identified loci that influence lipid concentrations and risk of coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2008;40:161–169. doi: 10.1038/ng.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Surakka I, et al. The impact of low-frequency and rare variants on lipid levels. Nat Genet. 2015;47:589–597. doi: 10.1038/ng.3300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manolio TA, et al. Finding the missing heritability of complex diseases. Nature. 2009;461:747–753. doi: 10.1038/nature08494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choquet H, Meyre D. Genetics of Obesity: What have we Learned? Curr Genomics. 2011;12:169–179. doi: 10.2174/138920211795677895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ng SB, et al. Exome sequencing identifies the cause of a mendelian disorder. Nat Genet. 2010;42:30–35. doi: 10.1038/ng.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen JC, Boerwinkle E, Mosley TH, Jr, Hobbs HH. Sequence variations in PCSK9, low LDL, and protection against coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1264–1272. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Do R, et al. Exome sequencing identifies rare LDLR and APOA5 alleles conferring risk for myocardial infarction. Nature. 2015;518:102–106. doi: 10.1038/nature13917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation106, 3143–3421 (2002). [PubMed]

- 16.Miller M, et al. Triglycerides and cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:2292–2333. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182160726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teslovich TM, et al. Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids. Nature. 2010;466:707–713. doi: 10.1038/nature09270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parra EJ, et al. Admixture mapping in two Mexican samples identifies significant associations of locus ancestry with triglyceride levels in the BUD13/ZNF259/APOA5 region and fine mapping points to rs964184 as the main driver of the association signal. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0172880. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou L, et al. A genome wide association study identifies common variants associated with lipid levels in the Chinese population. PLoS One. 2013;8:e82420. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tan A, et al. A genome-wide association and gene-environment interaction study for serum triglycerides levels in a healthy Chinese male population. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:1658–1664. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kettunen J, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies multiple loci influencing human serum metabolite levels. Nat Genet. 2012;44:269–276. doi: 10.1038/ng.1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Costanza MC, Beer-Borst S, James RW, Gaspoz JM, Morabia A. Consistency between cross-sectional and longitudinal SNP: blood lipid associations. Eur J Epidemiol. 2012;27:131–138. doi: 10.1007/s10654-012-9670-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ken-Dror G, Goldbourt U, Dankner R. Different effects of apolipoprotein A5 SNPs and haplotypes on triglyceride concentration in three ethnic origins. J Hum Genet. 2010;55:300–307. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2010.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature489, 57–74, 10.1038/nature11247 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Jeong SW, Chung M, Park SJ, Cho SB, Hong KW. Genome-wide association study of metabolic syndrome in koreans. Genomics Inform. 2014;12:187–194. doi: 10.5808/GI.2014.12.4.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bashliev I. [Temporary loss of work capacity in myocardial infarct patients who underwent rehabilitation] Vutr Boles. 1987;26:45–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carithers LJ, Moore HM. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) Project. Biopreserv Biobank. 2015;13:307–308. doi: 10.1089/bio.2015.29031.hmm. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hasumi H, et al. Folliculin-interacting proteins Fnip1 and Fnip2 play critical roles in kidney tumor suppression in cooperation with Flcn. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:E1624–1631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1419502112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Linehan WM, Srinivasan R, Schmidt LS. The genetic basis of kidney cancer: a metabolic disease. Nat Rev Urol. 2010;7:277–285. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2010.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.James VM, et al. Novel missense mutations in the glycine receptor beta subunit gene (GLRB) in startle disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2013;52:137–149. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al-Owain M, et al. Novel mutation in GLRB in a large family with hereditary hyperekplexia. Clin Genet. 2012;81:479–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Humphries AD, et al. Dissection of the mitochondrial import and assembly pathway for human Tom40. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:11535–11543. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413816200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salakhov RR, et al. [TOMM40 gene polymorphism association with lipid profile] Genetika. 2014;50:222–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Henkin L, et al. Genetic epidemiology of insulin resistance and visceral adiposity. The IRAS Family Study design and methods. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13:211–217. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(02)00412-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wing MR, et al. Analysis of FTO gene variants with obesity and glucose homeostasis measures in the multiethnic Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study cohort. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011;35:1173–1182. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tabb KL, et al. Analysis of whole exome sequencing with cardiometabolic traits using family-based linkage and association in the IRAS Family Study. Annals of Human Genetics. 2016 doi: 10.1111/ahg.12184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Almasy L, Blangero J. Multipoint quantitative-trait linkage analysis in general pedigrees. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:1198–1211. doi: 10.1086/301844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Connell JR, Weeks DE. PedCheck: a program for identification of genotype incompatibilities in linkage analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:259–266. doi: 10.1086/301904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gao C, et al. A Comprehensive Analysis of Common and Rare Variants to Identify Adiposity Loci in Hispanic Americans: The IRAS Family Study (IRASFS) PLoS One. 2015;10:e0134649. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alexander DH, Novembre J, Lange K. Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res. 2009;19:1655–1664. doi: 10.1101/gr.094052.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen H, Meigs JB, Dupuis J. Sequence kernel association test for quantitative traits in family samples. Genet Epidemiol. 2013;37:196–204. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hellwege JN, et al. Genome-wide family-based linkage analysis of exome chip variants and cardiometabolic risk. Genet Epidemiol. 2014;38:345–352. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goodarzi MO, et al. Insulin sensitivity and insulin clearance are heritable and have strong genetic correlation in Mexican Americans. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2014;22:1157–1164. doi: 10.1002/oby.20639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wagenknecht LE, et al. The insulin resistance atherosclerosis study (IRAS) objectives, design, and recruitment results. Ann Epidemiol. 1995;5:464–472. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(95)00062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Watanabe RM, et al. Transcription factor 7-like 2 (TCF7L2) is associated with gestational diabetes mellitus and interacts with adiposity to alter insulin secretion in Mexican Americans. Diabetes. 2007;56:1481–1485. doi: 10.2337/db06-1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Black MH, et al. Evidence of interaction between PPARG2 and HNF4A contributing to variation in insulin sensitivity in Mexican Americans. Diabetes. 2008;57:1048–1056. doi: 10.2337/db07-0848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li X, et al. Variation in IGF2BP2 interacts with adiposity to alter insulin sensitivity in Mexican Americans. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:729–736. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shu YH, et al. Evidence for sex-specific associations between variation in acid phosphatase locus 1 (ACP1) and insulin sensitivity in Mexican-Americans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:4094–4102. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Buchanan TA, et al. Preservation of pancreatic beta-cell function and prevention of type 2 diabetes by pharmacological treatment of insulin resistance in high-risk hispanic women. Diabetes. 2002;51:2796–2803. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.9.2796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Buchanan TA, et al. Response of pancreatic beta-cells to improved insulin sensitivity in women at high risk for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2000;49:782–788. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.5.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xiang AH, et al. Evidence for joint genetic control of insulin sensitivity and systolic blood pressure in hispanic families with a hypertensive proband. Circulation. 2001;103:78–83. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.103.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cheng LS, et al. Coincident linkage of fasting plasma insulin and blood pressure to chromosome 7q in hypertensive hispanic families. Circulation. 2001;104:1255–1260. doi: 10.1161/hc3601.096729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goodarzi MO, et al. Determination and use of haplotypes: ethnic comparison and association of the lipoprotein lipase gene and coronary artery disease in Mexican-Americans. Genet Med. 2003;5:322–327. doi: 10.1097/01.GIM.0000076971.55421.AD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goodarzi MO, et al. Lipoprotein lipase is a gene for insulin resistance in Mexican Americans. Diabetes. 2004;53:214–220. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.1.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goodarzi MO, et al. Variation in the gene for muscle-specific AMP deaminase is associated with insulin clearance, a highly heritable trait. Diabetes. 2005;54:1222–1227. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.4.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang Y-P, et al. Insulin and blood pressure are linked to the LDL receptor-related protein locus on chromosome 12q (Abstract) Diabetes. 2000;49((Supp 1)):A204. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Howie BN, Donnelly P, Marchini J. A flexible and accurate genotype imputation method for the next generation of genome-wide association studies. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000529. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.