Abstract

Glaucoma is the cause of irreversible blindness worldwide. Mutations in six genes have been associated with juvenile- and adult-onset familial primary open angle glaucoma (POAG) prior to this report but they explain only a small proportion of the genetic load. The aim of the study is to identify the novel genetic cause of the POAG in the families with adult-onset glaucoma. Whole exome sequencing (WES) was performed on DNA of two affected individuals, and predicted pathogenic variants were evaluated for segregation in four affected and three unaffected Dutch family members by Sanger sequencing. We identified a pathogenic variant (p.Val956Gly) in the PRPF8 gene, which segregates with the disease in Dutch family. Targeted Sanger sequencing of PRPF8 in a panel of 40 POAG families (18 Pakistani and 22 Dutch) revealed two additional nonsynonymous variants (p.Pro13Leu and p.Met25Thr), which segregate with the disease in two other Pakistani families. Both variants were then analyzed in a case-control cohort consisting of Pakistani 320 POAG cases and 250 matched controls. The p.Pro13Leu and p.Met25Thr variants were identified in 14 and 20 cases, respectively, while they were not detected in controls (p values 0.0004 and 0.0001, respectively). Previously, PRPF8 mutations have been associated with autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa (RP). The PRPF8 variants associated with POAG are located at the N-terminus, while all RP-associated mutations cluster at the C-terminus, dictating a clear genotype-phenotype correlation.

Keywords: Primary open angle glaucoma, Whole exome sequencing, Variant, Pathogenic, PRPF8

Introduction

Glaucoma is an irreversible optic neuropathy characterized by progressive degeneration of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs). It affects more than 70 million people worldwide with approximately 10% being bilaterally blind [1]. Glaucoma is also called a silent thief of the sight due to the damage of the peripheral vision first. Since glaucoma is typically asymptomatic until a substantial loss of vision has occurred, an even higher number of people is affected than the numbers estimated worldwide [2, 3]. Typically, glaucoma is classified as primary open angle (POAG) and angle closure glaucoma (PACG). POAG is the most common type of glaucoma affecting about 1–2% of individuals over the age of 40, with a higher prevalence among African individuals [4–6].

Despite the fact that glaucoma has different types and distinct etiologies, the death of the RGCs is a unifying theme, together with visual field defects and a characteristic optic nerve excavative atrophy [7, 8]. Since many years, research efforts have been made to elucidate the molecular mechanisms of the progressive optic nerve degeneration, but the underlying causes of the disease still remain poorly understood. Genome-wide association studies in case-control cohorts have identified several genetic variants associated with POAG, but they explain only a small proportion of the genetic load [9]. Although more than 15 loci have been identified for glaucoma till date, only five genes have been identified with the causative mutations which include the following: MYOC/TIGR [10, 11], OPTN [12, 13], ASB10 [14, 15], WDR36 [16], and EFEMP1 [17]. Mutations in sixth gene CYP1B1 were initially identified in the patients with the primary congenital glaucoma but later association has been reported in sporadic cases and families with both juvenile and adult-onset POAG. Mutations in MYOC are responsible for disease only in 4% of the JOAG and POAG cases with raised intraocular pressure (IOP) in an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance [11, 18]. The overall prevalence of OPTN mutations in POAG is 0.4%, and the role of WDR36 is still contradictory in glaucoma, even no difference in the phenotype was observed between the wild type and heterozygous mice for the WDR36 which makes it a weaker candidate for glaucoma. However, ASB10 [14, 15] and EFEMP1 [18, 19] were recently identified and the prevalence of patients with mutations in these genes is difficult to conclude. Overall, it has been estimated that less than 10% of POAG cases have pathogenic mutations in one of these genes. This suggests that a substantial percentage of patients may carry mutations in genes yet to be identified [20].

Following this rationale, we performed whole exome sequencing (WES) in two affected individuals of a family with adult-onset POAG to find the causative gene for this family.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Patients were recruited at the glaucoma departments of Radboud University Medical Center, The Netherlands and Al-Shifa Eye Trust Hospital, Pakistan. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Department of Ophthalmology, Radboud University Medical Center and Al-Shifa Eye Trust Hospital, and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The families included in the study have at least two affected individuals in the family. The sporadic POAG patients were included based on the absence of any incidence of glaucoma among the relatives of the patient. Written informed consent was obtained from affected and unaffected participants and/or their parents to participate in the study and for blood withdrawal. Genomic DNA was extracted using AutoPure LS DNA Extractor and PUREGEN reagents (Gentra Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA).

Clinical Examination

Complete ophthalmic examinations were performed for both sporadic and familial patients. The diagnosis of the POAG was made when the following criteria were met: briefly, absence of secondary glaucoma, an open anterior chamber angle by gonioscopy (Shaffer grade III or IV), higher IOP (>22 mmHg) measured using Goldmann applanation tonometry, a cup-to-disc ratio (CDR) >0.7 with thinning or notching of the disc rim, and nerve fiber layer defects. Visual field defects typical of glaucoma were determined with a Humphrey Field Analyzer (Zeiss Humphrey Systems, Dublin, CA, USA) and includes arcuate scotoma, nasal step, paracentral scotoma, and generalized depression. Only individuals affected with advanced primary open angle glaucoma were included in the study while normal tension glaucoma patients were excluded. The controls included in the study also underwent the clinical examination, and only individuals with the normal vision without any eye anomaly and no family history of glaucoma were included in the study.

Whole Exome and Sanger Sequencing

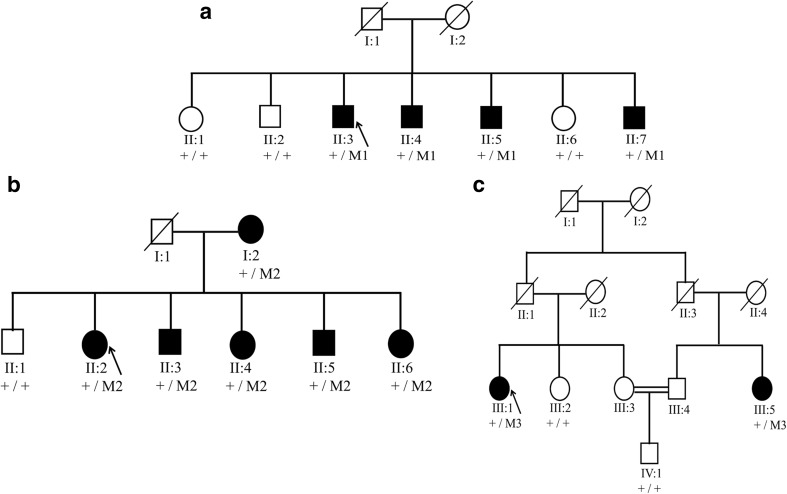

Whole exome sequencing (WES) was performed in two affected individuals of family A, (II:3 and II:4, Fig. 1a) with adult-onset POAG. The study adhered to the principles of the declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained prior to the study. Genomic DNA was extracted from the peripheral leukocytes of the family members. Enrichment of exonic sequences was achieved by using the SureSelectXT Human All Exon V.2 Kit (50 Mb), (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). Sequencing was performed on a SOLiD 4 sequencing platform (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The hg19 reference genome was aligned with the reads obtained using SOLiD LifeScope software V.2.1 (Life Technologies). The identified variants were validated and segregation analysis was performed in all available family members using standard PCR and Sanger sequencing. Sequencing was performed using the Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing-Ready Reaction Kit (Applied Biosystems) on a 3730 DNA automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) using standard protocols.

Fig. 1.

Segregation of PRPF8 variants in glaucoma families. a Family A with the heterozygous mutation c.2894T>G; p.Val965Gly (M1) in the PRFP8 gene. b Family B showing segregation of the variant (c.38C>T; p.Pro13Leu (M2). c Family C with the heterozygous variant c.74T>C; p.Met25Thr (M3) segregating with the disease

Data Processing

To identify the causative variant in this family, only variants shared by both affected individuals were considered for further analysis. All variants present within intergenic, intronic, and untranslated regions and synonymous substitutions were excluded. In addition, variants with an allele frequency >0.5 in public databases, including the dbSNP132 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP/) and Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC http://exac.broadinstitute.org/) databases, were excluded. Variants that were predicted not to be pathogenic by in-silico prediction including Sorting Intolerant from Tolerant (SIFT http://sift.bii.a-star.edu.sg/), MutationTaster (http://www.mutationtaster.org/), and Polymorphism Phenotyping (PolyPhen-2 http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/), variants with a low PhyloP score (<2.7) or a low Grantham score (<80) were also excluded. The variants that remained after these filtering steps were validated by Sanger sequencing, and segregation analysis was performed in the family. Amino acid conservation of mutated residue among the orthologous species was assessed by performing the aligned using Vector NTI Advance (TM) 2011 software. The amino acid sequences were obtained from protein sequence database UniProt (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/protein/Q6P2Q9).

Results

Mutation Identification

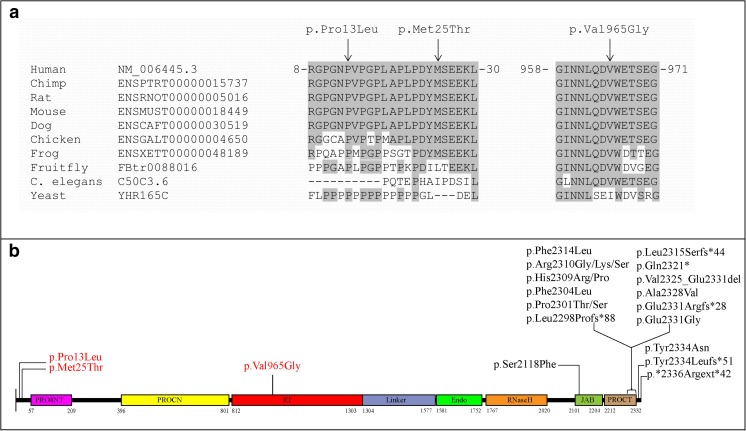

Only the rare variants shared between two affected individuals of the family were further considered for validation by Sanger sequencing (Table 1). Segregation analysis was performed for >20 variants based on the in-silico prediction and expression in the eye. Only one novel variant (c.2894T>G; p.Val965Gly) in the PRPF8 gene was identified that segregates with the disease in family A (Fig. 1a). This variant was predicted to be deleterious by SIFT, probably damaging by PolyPhen-2 and disease causing by Mutation Taster. The wildtype nucleotide was highly conserved (phyloP score 5.13), and the amino acid residue p.Val965 was highly conserved among different orthologues (Fig. 2a). The p.Val965Gly variant was not present in the dbSNP132 or ExAc databases, nor was it identified in 150 Dutch control individuals.

Table 1.

Number of variants identified by WES in two affected individuals of family A

| Filtering Steps | Individual II:3 | Individual II:4 | Shared variants for both individuals |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total variants | 45.953 | 46.860 | 31.622 |

| SNP frequency <0.5 | 29.020 | 29.688 | 16.645 |

| In-house frequency <0.5 | 2.431 | 2.519 | 476 |

| Exonic and canonical splice sites | 887 | 900 | 175 |

| Nonsynonmous | 646 | 638 | 123 |

| Grantham score >80 | 281 | 274 | 41 |

| Phylop >2.7 | 234 | 231 | 46 |

Fig. 2.

a Multiple sequence alignment of PRPF8 orthologues. Conserved amino acids are shaded, and the positions of mutated amino acids p.Pro13Leu (P), p.Met25Thr (M), and p.Val965Gly (V) are indicated with an arrow. b Distribution of PRPF8 mutations in different domains. Conserved domains, PrP8 N-terminal domain (PRO8NT), central N-terminal domain in pre-mRNA splicing factors of PRO8 family (PROCN), reverse transcriptase homology domain (RT), restriction endonuclease homology domain (Endo), ribonuclease H homology domain (RNase H), JAB1/Mov34/MPN/PAD-1 ubiquitin protease (JAB), C-terminal domain in pre-mRNA splicing factors of PRO8 family (PROCT). Mutations (indicated in red) associated with autosomal dominant (ad) POAG are all located at the C-terminus of the protein while adRP mutations (indicated in black) are all located at the N-terminus

Clinical Findings of Family A

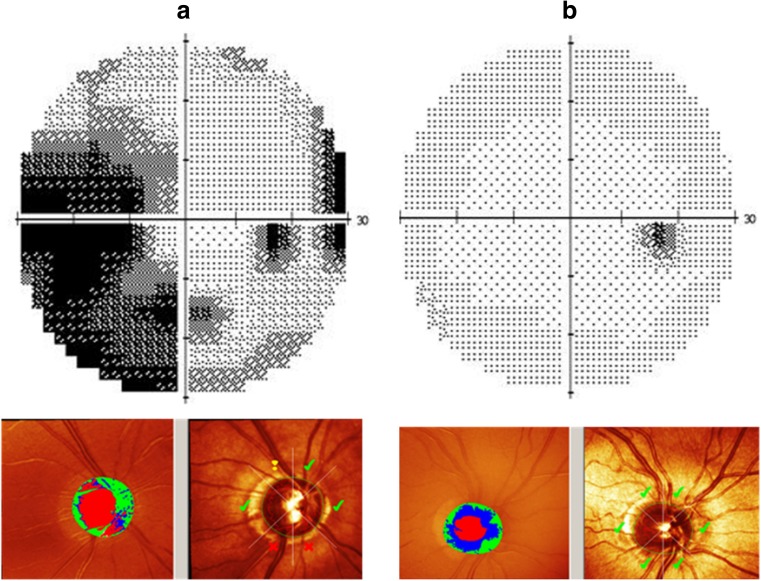

The four affected individuals of family A (Fig. 1a) were diagnosed with POAG. They all had bilateral glaucomatous optic neuropathy with a cup-to-disc ratio (CDR) >0.7 on fundoscopy with compatible glaucomatous visual field loss. The intraocular pressure (IOP) was >22 mmHg, and the anterior chamber angles were open in all affected individuals. They also showed abnormal results on Heidelberg Retina Tomography (HRT) II testing. The visual field and the HRT analysis of the 67-year-old proband (family A, individual II:3) and those of a 60-year-old, unaffected male sibling (family A, individual II:2) are shown in Fig. 3. The three unaffected siblings did not show any (glaucomatous) optic neuropathy nor visual field loss as present in the four affected siblings.

Fig. 3.

Phenotypic characterization of the right eyes of two representative individuals of family A with the pathogenic variant in the PRPF8 gene. Each panel has two parts; the upper part depicts the visual field printouts of the Humphrey Field Analyzer (HFA), and the lower part shows screenshots from Heidelberg Retina Tomograph II (HRT) analysis to detect loss of the papillary neuroretinal rim. a HFA and HRT results for the 67-year-old proband (individual II-3 of family A) are shown. The large dark areas in the HFA results correspond to glaucomatous scotomas due to nerve fiber layer defects. HRT scans demonstrate glaucomatous increased optic disc cupping and suspect (exclamation marks) or manifest pathological (crosses) neuroretinal rim measures (according to the Moorfield’s regression analysis) within the different quadrants of the optic disc. b HFA and HRT results for a 61-year-old, unaffected sibling (individual II-2 of family A) of the proband are shown for comparison. HFA results indicate that there is no darkening due to glaucomatous defects on HFA. The small temporal black area corresponds to the physiological blind spot. HRT results (with only green tick marks) show no thinning of the neuroretinal rim

Panel Screening for PRPF8

Sanger sequencing of the entire open reading frame of PRPF8 in a cohort of 40 adult-onset POAG families (n = 18 Pakistani and n = 22 Dutch) having at least two affected individuals was performed. Sequencing identified two additional nonsynonymous variants, c.38C>T; p.Pro13Leu and c.74T>C; p.Met25Thr, which segregate with the disease in families B and C, respectively (Fig. 1b, c). Affected individuals in both families were diagnosed with adult-onset POAG, with an IOP >21 mmHg and a CDR >0.7.

Both variants are localized in exon 2 of the PRPF8 gene. Therefore, exon 2 was Sanger sequenced in a case-control cohort consisting of 320 Pakistani POAG patients and 250 Pakistani controls. The p.Pro13Leu and p.Met25Thr variants were identified in 14 and 20 cases, respectively, while they were not detected in controls (p values 0.0004 and 0.0001, respectively). The p.Pro13Leu and p.Met25Thr variants were present in the ExAC database, with allele frequencies of 0.00014 (16/113928 individuals) for p.Pro13Leu and 0.00002 (3/115076 individuals) for p.Met25Thr, respectively. The wildtype nucleotide and amino acid residues are highly conserved among different orthologues (Fig. 2a).

Discussion

The precursor mRNA-processing factor 8 (PRPF8) is the core component of the U5 snRNP. It is the largest and most evolutionarily conserved protein, central to the dynamics of the spliceosome [21, 22]. As a key part of the catalytic core of the spliceosome, it not only makes direct interactions with the 5′ splice site, branch point, and 3′ splice site in the pre-mRNA, but also engages the U5 and U6 snRNAs and the excised intron [23, 24]. Previous studies have indicated a crucial role of PRPF8 in the vast majority of pre-mRNA splicing and its requirement in all tissues [25, 26]. PRPF8 is responsible for processing of the majority of intron-containing transcripts, including alternatively spliced mRNAs in higher eukaryotes [27]. Mutations in human PRPF8 that affects spliceosome assembly and function are found in autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa (RP) (OMIM 600059), characterized by a progressive degeneration of the rod and cone photoreceptors in the retina [28–30]. All germline mutations reported in the PRPF8 gene in patients with RP are clustered at the C-terminus of the protein.

PRPF8 interacts with other proteins at both the N-terminal and C-terminal of the protein. Mutations previously identified in RP are all localized at the C-terminus of the protein and affect the binding of the interacting partners with the C-terminus of the PRPF8 protein. Pathogenic mutations in the Jab1/MPN domain of human PRPF8 have been described in RP [28], and mutations of equivalent residues in the yeast Jab1/MPN domain disrupt its interaction with Brr2 [31]. Brr2 is involved in catalyzing the separation of the U4/U6 snRNA duplex [32]. In addition, the prp8–1 allele G2347D was observed to have a detrimental effect on the interaction of Prp8p with Brr2 in yeast two-hybrid and coimmunoprecipitation assays [33]. These studies help to elucidate that mutations involved in RP at the C-terminus of the PRPF8 disrupt the interactions with the interacting partners important for the splicing.

In the current study, we identified mutations located at the N-terminus of PRPF8 associated with glaucoma. We postulate that these variants can disrupt the interaction of PRPF8 with its interacting partners at the N-terminus of the protein, such as PRP39 and PRP40 [22]. All three variants identified in glaucoma are predicted to be pathogenic using different pathogenicity programs and reside within these interacting domains. Biochemical studies are needed to determine whether these variants indeed interrupt these interactions.

Human mRNA expression studies have shown that PRPF8 is highly expressed in the retinal inner nuclear layer containing the bipolar cells, horizontal cells, amacrine cells, and Müller glia cells, as well as in the retinal ganglion cell layer. In the photoreceptor cells, the expression of PRFP8 is comparatively lower [34]. POAG is characterized by loss of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs), large and complex cells extending from the inner retina. The convergence of the axons of RGCs at the optic disc creates the neuroretinal rim. In POAG, the loss of the RGC axons leads to progressive thinning of this neuroretinal rim of the optic nerve, thereby enlarging the optic nerve cup. Since PRPF8 is highly expressed in RGC axons, pathogenic variants in PRPF8 could affect the function of the spliceosomal machinery in these cells and thus induce POAG.

The identification of three variants in PRPF8 suggests that POAG may be a splicing disease. The PRPF8 variants associated with POAG are located at the N-terminus, while all RP-associated mutations cluster at the C-terminus, dictating a clear genotype-phenotype correlation.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Stichting Blindenhulp, a Shaffer grant from the Glaucoma Research Foundation, the Glaucoomfonds, Oogfonds, and the Algemene Nederlandse Vereniging ter Voorkoming van Blindheid for providing financial support.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Patient Consent

Patient consent was obtained.

Ethics Approval

Radboud University Medical Center, The Netherlands and Al-Shifa Eye Trust Hospital, Pakistan.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Quigley HA, Broman AT. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(3):262–267. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.081224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leite MT, Sakata LM, Medeiros FA. Managing glaucoma in developing countries. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2011;74(2):83–84. doi: 10.1590/S0004-27492011000200001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rotchford AP, Kirwan JF, Muller MA, Johnson GJ, Roux P. Temba glaucoma study: a population-based cross-sectional survey in urban South Africa. Ophthalmology. 2003;110(2):376–382. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(02)01568-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedman DS, Wolfs RC, O'Colmain BJ, Klein BE, Taylor HR, West S, Leske MC, Mitchell P, Congdon N, Kempen J. Prevalence of open-angle glaucoma among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122(4):532–538. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Day AC, Baio G, Gazzard G, Bunce C, Azuara-Blanco A, Munoz B, Friedman DS, Foster PJ. The prevalence of primary angle closure glaucoma in European derived populations: a systematic review. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96(9):1162. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-301189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tielsch JM, Sommer A, Witt K, Katz J, Royall RM. Blindness and visual impairment in an American urban population. The Baltimore eye survey. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990;108(2):286–290. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1990.01070040138048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calkins DJ. Critical pathogenic events underlying progression of neurodegeneration in glaucoma. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2012;31(6):702–719. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morgan JE. Retina ganglion cell degeneration in glaucoma: an opportunity missed? A review. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2012;40(4):364–368. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2012.02789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bailey JN, Loomis SJ, Kang JH, Bailey JN, Loomis SJ, Kang JH, Allingham RR, Gharahkhani P, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies TXNRD2, ATXN2 and FOXC1 as susceptibility loci for primary open-angle glaucoma. Nat Genet. 2016;48(2):189–194. doi: 10.1038/ng.3482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheffield VC, Stone EM, Alward WL, Sheffield VC, Stone EM, Alward WL, Drack AV, Johnson AT, Streb LM, Nichols BE. Genetic linkage of familial open angle glaucoma to chromosome 1q21-q31. Nat Genet. 1993;4(1):47–50. doi: 10.1038/ng0593-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stone EM, Fingert JH, Alward WL, Nguyen TD, Polansky JR, Sunden SL, Nishimura D, Clark AF, Nystuen A, Nichols BE, Mackey DA, Ritch R, Kalenak JW, Craven ER, Sheffield VC. Identification of a gene that causes primary pen angle glaucoma. Science. 1997;275(5300):668–670. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5300.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rezaie T, Child A, Hitchings R, Brice G, Miller L, Coca-Prados M, Héon E, Krupin T, Ritch R, Kreutzer D, Crick RP, Sarfarazi M. Adult-onset primary open-angle glaucoma caused by mutations in optineurin. Science. 2002;295(5557):1077–1079. doi: 10.1126/science.1066901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarfarazi M, Child A, Stoilova D, Brice G, Desai T, Trifan OC, Poinoosawmy D, Crick RP. Localization of the fourth locus (GLC1E) for adult-onset primary open-angle glaucoma to the 10p15-p14 region. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62(3):641–652. doi: 10.1086/301767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wirtz MK, Samples JR, Rust K, Lie J, Nordling L, Schilling K, Acott TS, Kramer PL. GLC1F, a new primary open-angle glaucoma locus, maps to 7q35-q36. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117(2):237–241. doi: 10.1001/archopht.117.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pasutto F, Keller KE, Weisschuh N, Sticht H, Samples JR, Yang YF, Zenkel M, Schlötzer-Schrehardt U, Mardin CY, Frezzotti P, Edmunds B, Kramer PL, Gramer E, Reis A, Acott TS, Wirtz MK. Variants in ASB10 are associated with open-angle glaucoma. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21(6):1336–1349. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monemi S, Spaeth G, DaSilva A, Popinchalk S, Ilitchev E, Liebmann J, Ritch R, Héon E, Crick RP, Child A, Sarfarazi M. Identification of a novel adult-onset primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) gene on 5q22.1. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14(6):725–733. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mackay DS, Bennett TM, Shiels A. Exome sequencing identifies a missense variant in EFEMP1 co-segregating in a family with autosomal dominant primary open-angle glaucoma. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0132529. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suriyapperuma SP, Child A, Desai T, Brice G, Kerr A, Crick RP, Sarfarazi M. A new locus (GLC1H) for adult-onset primary open-angle glaucoma maps to the 2p15-p16 region. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125(1):86–92. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stoilov I, Akarsu AN, Sarfarazi M. Identification of three different truncating mutations in cytochrome P4501B1 (CYP1B1) as the principal cause of primary congenital glaucoma (Buphthalmos) in families linked to the GLC3A locus on chromosome 2p21. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6(4):641–647. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.4.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwon YH, Fingert JH, Kuehn MH, Alward WL. Primary open-angle glaucoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(11):1113–1124. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mordes D, Luo X, Kar A, Kuo D, Xu L, Fushimi K, Yu G, Sternberg P, Jr, Wu JY. Pre-mRNA splicing and retinitis pigmentosa. Mol Vis. 2006;12:1259–1271. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grainger RJ, Beggs JD. Prp8 protein: at the heart of the spliceosome. RNA. 2005;11(5):533–557. doi: 10.1261/rna.2220705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galej WP, Oubridge C, Newman AJ, Nagai K. Crystal structure of Prp8 reveals active site cavity of the spliceosome. Nature. 2013;493(7434):638–643. doi: 10.1038/nature11843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Konforti BB, Konarska MM. U4/U5/U6 snRNP recognizes the 5′ splice site in the absence of U2 snRNP. Genes Dev. 1994;8(16):1962–1973. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.16.1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luo HR, Moreau GA, Levin N, Moore MJ. The human Prp8 protein is a component of both U2- and U12-dependent spliceosomes. RNA. 1999;5(7):893–908. doi: 10.1017/S1355838299990520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schellenberg MJ, Wu T, Ritchie DB, Fica S, Staley JP, Atta KA, LaPointe P, MacMillan AM. A conformational switch in PRP8 mediates metal ion coordination that promotes pre-mRNA exon ligation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20(6):728–734. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoskins AA, Moore MJ. The spliceosome: a flexible, reversible macromolecular machine. Trends Biochem Sci. 2012;37(5):179–188. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McKie AB, McHale JC, Keen TJ, Tarttelin EE, Goliath R, van Lith-Verhoeven JJ, Greenberg J, Ramesar RS, Hoyng CB, Cremers FP, Mackey DA, Bhattacharya SS, Bird AC, Markham AF, Inglehearn CF. Mutations in the pre-mRNA splicing factor gene PRPC8 in autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa (RP13) Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10(15):1555–1562. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.15.1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tanackovic G, Ransijn A, Thibault P, Abou Elela S, Klinck R, Berson EL, Chabot B, Rivolta C. PRPF mutations are associated with generalized defects in spliceosome formation and pre-mRNA splicing in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20(11):2116–2130. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pena V, Liu S, Bujnicki JM, Lührmann R, Wahl MC. Structure of a multipartite protein-protein interaction domain in splicing factor prp8 and its link to retinitis pigmentosa. Mol Cell. 2007;25(4):615–624. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maeder C, Kutach AK, Guthrie C. ATP-dependent unwinding of U4/U6 snRNAs by the Brr2 helicase requires the C terminus of Prp8. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16(1):42–48. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raghunathan PL, Guthrie C. RNA unwinding in U4/U6 snRNPs requires ATP hydrolysis and the DEIH-box splicing factor Brr2. Curr Biol. 1998;8(15):847–855. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(07)00345-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Nues RW, Beggs JD. Functional contacts with a range of splicing proteins suggest a central role for Brr2p in the dynamic control of the order of events in spliceosomes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2001;157(4):1451–1467. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.4.1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trifunovic D, Karali M, Camposampiero D, Ponzin D, Banfi S, Marigo V. A high-resolution RNA expression atlas of retinitis pigmentosa genes in human and mouse retinas. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49(6):2330–2336. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]