Abstract

Inherited hemoglobin disorders include thalassemias and structural variants like HbS, HbE, and HbD, Hb Lepore, HbD-Iran, Hb-H disease and HbQ India. HbQ India is an uncommon alpha-chain structural hemoglobin variant seen in North and West India. Patients are mostly asymptomatic and often present in the heterozygous state or co-inherited with beta-thalassaemia. This study was done in a tertiary care teaching hospital in North India over a period of 7 years among patients referred from antenatal and other clinics for screening of hemoglobin disorders. Complete blood count, peripheral blood smear examination and cation exchange high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was done to quantify various hemoglobins. HbQ India was diagnosed if the unknown variant hemoglobin was detected within the characteristic retention window. Of a total of 7530 patients screened, 31 (0.4%) were detected to have HbQ India. Of these, 25 (0.3%) patients had HbQ India trait and 6 (0.1%) patients had compound heterozygosity for HbQ India and Beta Thalassemia trait (HbQ India-BTT). All patients were clinically asymptomatic and were detected as part of the screening for hemoglobin disorders. Only two patients with HbQ India-BTT had hemoglobin less than 10 g/dL. In 25 patients with HbQ India trait, HbQ ranged from 13.6 to 24.4% and in 6 patients with HbQ India-BTT, HbQ India ranged from 7.4 to 9.0%. HbQ India is an uncommon structural hemoglobin variant. Although asymptomatic, it may cause diagnostic difficulty in the compound heterozygous state with beta thalassemia. HPLC provides a rapid, accurate and reproducible method for screening of this condition to identify and counsel individuals.

Keywords: Beta thalassemia, HbQ India, HPLC, Structural variant

Introduction

Inherited abnormalities of hemoglobin synthesis include a variety of disorders ranging from decreased production of alpha or beta globin chains to structurally abnormal hemoglobin variants. Common hemoglobin disorders in India include alpha and beta thalassemia along with structural variants such as HbS, HbE, and HbD Punjab and their compound heterozygous states. Some of the less commonly found hemoglobin variants in India that are detected during screening programs are Hb Lepore, HbD-Iran, HbJ-Meerut, Hb-H disease and HbQ India [1]. Identification of the hemoglobin disorders is important in prognostication, management, genetic counselling and in formulation of preventive strategies.

HbQ India (HbA1:c. 193 G > C), is a relatively uncommon alpha-chain structural hemoglobin variant caused by an amino acid substitution of histidine for aspartic acid at codon 64 of the alpha1-globin gene. It usually presents in the heterozygous state or is co-inherited with beta-thalassaemia [2]. This paper presents clinical and hematological profile of patients with HbQ India seen in a tertiary care teaching hospital.

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted in the hematopathology section of the Department of Pathology in a tertiary care teaching hospital in North India. A total of 7530 patients over a period of 7 years screened for beta thalassemia and other abnormal hemoglobins were included. The patients were referred from the antenatal clinic under the antenatal thalassemia screening program. Whenever the antenatal case was detected positive for a hemoglobin disorder, partner screening was done and the couple suitably counselled. Patients also included those referred from other out-patient clinics and inpatients when hemoglobin disorders were suspected based on a suggestive family history, clinical profile or red cell indices.

Ethylene diamine tetra acetic acid (EDTA) anticoagulated blood samples were collected from the patients. Complete blood count was done on LH750 (Beckman Coulter) automated hematology analyser. Leishman stained blood smears of all the samples were examined.

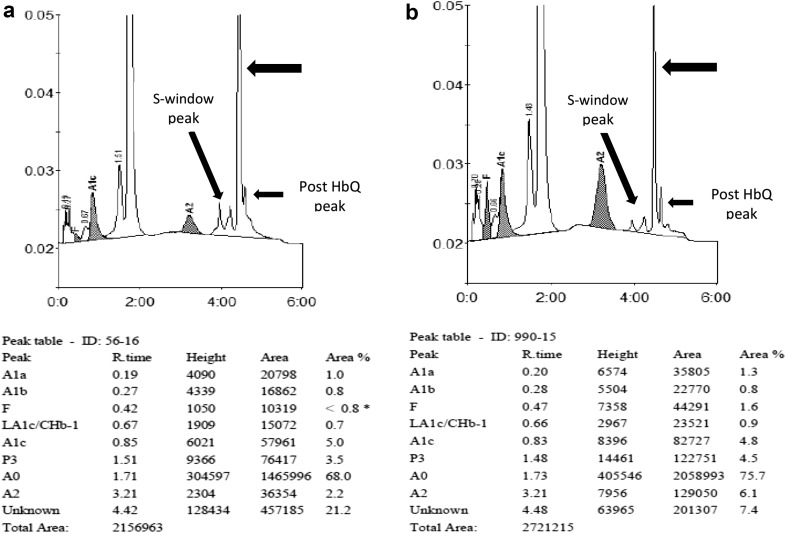

Cation exchange-high performance liquid chromatography (CE-HPLC) was done on BioRad Variant-I using the Beta-thal short program (initial 2 years) and BioRad D10 Hemoglobin Testing System (D10 dual HbA2/F/A1c program) as per the manufacturer’s guidelines. These were used to quantify HbA2, HbF and HbA along with other hemoglobin variants like HbS, HbD, HbE or HbQ India. The peaks in the chromatograms were identified with reference to retention time, relative percentage and area under curve as compared to normal individuals (Fig. 1). HbQ India was diagnosed if the variant hemoglobin was detected with a characteristic retention window of 4.47 ± 0.03 min in the Biorad D10 instrument and 4.76 ± 0.01 min in the Biorad Variant instrument. The HbA2 cut off used to diagnose beta thalassemia trait was >4.0%. Values between 3.5 and 4.0% were considered to be borderline. Iron studies, electrophoresis and molecular testing were not done in the patients.

Fig. 1.

a Shows the HPLC chromatogram from Biorad D10 instrument in a patient with HbQ India trait. Note the additional unknown peak (arrow) with hemoglobin of 21.2% and a retention time of 4.42 min. b Shows the HPLC chromatogram in a patient with HbQ India-Beta thalassemia trait. The additional unknown peak (arrow) for HbQ India (7.4%) is seen with a retention time of 4.48 min. HbA2 is also raised (6.1%). Minor post HbQ and S window peaks are also seen in both cases

Results

In the present study a total of 7530 patients were screened for haemoglobin disorders. Thirty-one (0.4%) patients had HbQ India (Fig. 1a), of which 25 (0.3%) patients were found to have HbQ India trait and 6 (0.1%) patients had compound heterozygosity for HbQ India and Beta Thalassemia trait (HbQ India-BTT) (Fig. 1b). There were no patients with homozygosity for HbQ India. All patients were clinically asymptomatic and were detected as part of the screening for hemoglobin disorders. In one couple, both partners had HbQ India trait. The couple was counselled regarding the paucity of data in high gene dosage HbQ cases and a second opinion was advised. However, they were lost to follow up.

Hematological Parameters

Of the 31 patients with HbQ India, 2 had hemoglobin less than 10 g/dL. Both these patients were compound heterozygotes for HbQ India and BTT. The hematological profile of the patients with HbQ India included in the study is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Hematological parameters in patients with HbQ India trait and HbQ India-Beta thalassemia trait (BTT) compound heterozygous state

| Hematological parameters | HbQ India trait (n = 25)# |

HbQ India-BTT (n = 6)* |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | Mean ± SD (95% CI) |

Range | Mean ± SD (95% CI) |

|

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 10.1–17.2 | 12.6 ± 1.7 (12.0–13.4) |

8.6–14.5 | 10.9 ± 2.2 (8.1–13.8) |

| RBC count (×106/µL) | 3.2–5.7 | 4.4 ± 0.6 (4.2–4.7) |

4.1–6.6 | 5.4 ± 0.9 (4.3–6.6) |

| HCT (%) | 30.9–47.3 | 37.4 ± 4.4 (35.6–39.5) |

24.3–46.9 | 34.5 ± 8.2 (24.3–44.7) |

| MCV (fL) | 76.8–95.2 | 84.7 ± 6.0 (82.2–87.4) |

58.5–70.5 | 62.9 ± 4.4 (57.4–68.6) |

| MCH (pg) | 23.5–33.6 | 28.7 ± 2.7 (27.6–29.9) |

18.8–21.8 | 20.1 ± 1.2 (18.6–21.6) |

| MCHC (g/dL) | 30.5–36.3 | 33.8 ± 1.7 (33.1–34.6) |

29.9–35.4 | 32.0 ± 2.1 (29.3–34.7) |

| Platelets (×103/µL) | 151.0–396.0 | 287.8 ± 76.2 (179.8–294.9) |

231–335 | 280 ± 45.3 (223.7–336.2) |

| TLC (×103/µL) | 5.7–13.7 | 9.3 ± 2.0 (6.7–12.4) |

5.7–11.6 | 9.6 ± 2.3 (8.4–10.3) |

| HbA (%) | 74.2–84.7 | 79.77 ± 2.21 (78.8–80.7) |

81.7–85.6 | 83.91 ± 1.41 (82.4–85.4) |

| HbF (%) | 0.0–1.3 | 0.45 ± 0.42 (0.3–0.6) |

0.6–4.7 | 2.21 ± 1.69 (0.4–3.4) |

| HbA2 (%) | 0.9–3.2 | 2.28 ± 0.64 (2.0–2.5) |

4.9–6.1 | 5.58 ± 0.48 (5.1–6.1) |

| HbQ India (%) | 13.6–24.4 | 17.49 ± 2.30 (16.5–18.4) |

7.4–9.0 | 8.28 ± 0.70 (7.5–9.0) |

CBC data was not available for 2 patients# and 1 patient*

HPLC Parameters

In 25 patients with HbQ India trait, HbQ ranged from 13.6 to 24.4% and in 6 patients with HbQ India-BTT, HbQ ranged from 7.4 to 9.0%. The percentage of the hemoglobins detected is shown in Table 1.

Minor additional peaks were also seen. In one patient, HPLC chromatogram could not be interpreted as the tracing had faded; the numerical data though was documented in this patient. Of the chromatograms in the remaining 30 patients, 28 showed post HbQ peak, 17 showed S-window peak (Fig. 1a) and 8 showed split HbA2 peak. Post HbQ and S-window was the most frequent combination observed in 16/30 patients. Six patient showed concomitant post HbQ and split HbA2 peak. The combination of all three minor peaks was not seen in any patient.

Discussion

HbQ India is a rare hemoglobinopathy with a prevalence of 0.4% in the Indian subcontinent [2]. In a study in northern India (including New Delhi, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh and Jammu and Kashmir) and Nepal, conducted in 2010 on 2600 patients, the prevalence of HbQ India was reported to be 0.2% [3]. Panigrahi et al. [4] in their study on 4500 patients in 2005 reported a prevalence of 0.4%. In our study, we found the overall prevalence of HbQ India to be 0.3% which is comparable to previous reports.

HbQ was first described by Vella et al. [5] in 1958 in association with alpha thalassaemia in a Chinese patient. The first case of HbQ India was reported by Sukumaran [6] in a Sindhi family with associated β Thalassemia. HbQ has three molecular structural variants. These are HbQ Thailand (alpha 74 Asp to His), HbQ Iran (alpha 75 Asp to His) and HbQ India (alpha 64 Asp to His). HbQ India is found predominantly in individuals from western and northern India and is more common in the Sindhi population [7]. It is characterized by the replacement of aspartic acid by histidine at the 64th codon on the alpha1 gene [8]. The quantity of HbQ variant is usually determined by the ratio of alpha A, alpha Q and beta A globin chains [9].

HbQ India commonly occurs in the heterozygous form and can also be associated with thalassemia [10]. Phanasgaonkar et al. [2] in a study of 64 patients with HbQ India reported 36 cases of HbQ India trait, 22 of HbQ India-BTT, 3 cases of HbQ India-beta thalassemia major and 3 cases of HbQ India homozygous.

Individuals inheriting HbQ India are clinically silent with normal or mildly deranged hematological parameters and are generally incidentally detected during population or family screening [2, 9, 11]. Although rare, the combination of HbQ India and Hb-H may be more symptomatic with chronic anemia, hepatosplenomegaly and jaundice [12]. The mutation α64 (E 13) involved in HbQ India is on the surface of the hemoglobin tetramer and the charge changes at these positions do not affect the properties of the hemoglobin molecule leading to a clinically silent phenotype [8, 10]. Even its presence with beta thalassemia trait does not produce any clinical abnormality and patients are mostly asymptomatic [9]. The clinical profile of patients in the present study was similar to those as reported by other authors. In an earlier report only 1 of the 3 HbQ India homozygous cases presented with hepatomegaly and required blood transfusions [2].

The asymptomatic clinical profile of patients carries a possible challenge in the diagnosis of HbQ India. The purpose of the screening tests is to allow parents or individuals to make choices based on correct and relevant information. The common methods used are complete blood count with red cell indices and hemoglobin variant detection by hemoglobin electrophoresis and/or HPLC [8]. A major hindrance in the diagnosis is a normal hematology profile and misinterpretation of HbQ as HbS/HbD/HbG on alkaline agarose gel electrophoresis because of the same electrophoretic mobility [3, 8].

HPLC offers advantage over classic hemoglobin electrophoresis. It is a rapid, sensitive, specific and reproducible technique. HPLC is a valuable tool in the detection of thalassemia and hemoglobinopathies including rare hemoglobin variants. It also provides and accurate quantification of various hemoglobins [8]. HbQ India produces a characteristic sharp narrow unknown peak with a retention time of 4.46 and 4.77 ± 0.01 min on the Biorad D10 and Biorad Variant instruments (Beta Thal Short Program) respectively [1, 3, 11]. In our study also an unknown peak in the retention time window of 4.47 ± 0.03 and 4.76 ± 0.01 min was seen just after the HbS window on the Biorad D10 and Biorad Variant instruments (Beta Thal Short Program) respectively.

A recent study has reported additional minor peaks in patients with HbQ India. These were split HbA2 peak, Post HbQ peak and small S-window peak. Our study also has showed similar findings with minor additional peaks (Split HbA2, Post HbQ India and HbS0). The authors in the previous study have suggested post translational modification of HbQ India, glycosylation or carry over in case of minor HbS peaks in their patients [13].

In our study HbQ India level ranged from 13.6 to 24.4 and 7.4 to 9.0% in patients with HbQ-India trait and HbQ-India-Beta Thalassemia Trait respectively. On HPLC, the level of HbQ in HbQ India homozygous patients range from 32 to 35%, while in HbQ heterozygotes, the level is 20%. When there is an interaction of beta-thalassaemia heterozygotes, the level is about 14%, and in interacting beta-thalassaemia homozygotes, the levels range from 7 to 9% [2]. The level of HbQ India in our study was comparable to those reported by other studies.

Conclusion

HbQ India is an uncommon structural variant haemoglobin. Although asymptomatic, it may have manifestations due to interactions in cases with compound heterozygous and homozygous states of other hemoglobinopathies. Although hemogram findings are normal and hemoglobin electrophoresis may be ambiguous, HPLC provides a rapid, accurate and reproducible method for screening of this condition to identify and counsel individuals.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support given by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), New Delhi as most of the patients had been worked up during an ICMR funded screening project.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. No patient/subject identifying information has been disclosed in the manuscript. No patient/subject intervention was done and the subjects were not exposed to any risks during the study.

Informed Consent

Since the study involved a retrospective review of data only from routine testing offered by the laboratory, separate informed consent was not taken for the study. “For this type of study formal consent is not required.”

References

- 1.Rao S, Kar R, Gupta SK, Chopra A, Saxena R. Spectrum of haemoglobinopathies diagnosed by cation exchange-HPLC and modulating effects of nutritional deficiency anaemias from North India. Indian J Med Res. 2010;132:513–519. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.73390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Phanasgaonkar S, Colah R, Ghosh K, Mohanty D, Gupte S. Hb Q(India) and its interaction with beta-thalassaemia: a study of 64 cases from India. Br J Biomed Sci. 2007;64:160–163. doi: 10.1080/09674845.2007.11732780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sachdev R, Dam AR, Tyagi G. Detection of Hb varaints and hemoglobinopathies in India population using HPLC: report of 2600 cases. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2010;53:57–62. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.59185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Panigrahi I, Bajaj J, Chatterjee T, Saxena R, Mahapatra M, Pati HP. Hb Q India: Is it always benign? Am J Hematol. 2005;78:245–246. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vella F, Wells RH, Ager JA, Lehmann H. A haemoglobinopathy involving haemoglobin H and a new (Q) haemoglobin. Br Med J. 1958;1:752–755. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5073.752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sukumaran PK, Merchant SM, Desai MP, Wiltshire BG, Lehmann H. Haemoglobin Q India (alpha 64(E13) aspartic acid histidine) associated with beta-thalassemia observed in three Sindhi families. J Med Genet. 1972;9:436–442. doi: 10.1136/jmg.9.4.436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mutreja D, Tyagi S, Tejwani N, Dass J. Double heterozygous hemoglobin Q India/hemoglobin D Punjab hemoglobinopathy: report of two rare cases. Indian J Hum Genet. 2013;19:479–482. doi: 10.4103/0971-6866.124381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaler AK, Veeranna V, Bai U, Raja P, Kaur P. Role of HPLC in the diagnosis of hemoglobin Q disease. IJHSR. 2013;3:96–99. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abraham R, Thomas M, Britt R, Fisher C, Old J. Hb Q-India: an uncommon variant diagnosed in three Punjabi patients with diabetes is identified by a novel DNA analysis test. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:296–299. doi: 10.1136/jcp.56.4.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pérez SM, Noguera NI, Acosta IL, Calvo KL, Bragós IM, Rescia V, et al. Compound heterozygosity of Hb Q India (α64 (E13) ASP → HIS) and −α3,7 thalassemia. First report from Argentina. Revista Cubana de Hematologia, Inmunologia y Hemoterapia. 2010;22:236–240. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhat VS, Dewan KK, Krishnaswamy PR, Mandal AK, Balaram P. Characterization of a hemoglobin variant: HbQ-India/IVS 1–1 [G > T]-β-thalassemia. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2010;25:99–104. doi: 10.1007/s12291-010-0020-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leung KF, Ma Es, Chan AY, Chan LC. Clinical phenotype of hemogobin Q-H disease. J Clin Pathol. 1981;57:81–82. doi: 10.1136/jcp.57.1.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma S, Sharma P, Das R, Chhabra S, Hira JK. HbQ-India (HBA1:c.193G> C): hematological profiles and unique CE-HPLC findings of potential diagnostic utility in 65 cases. Ann Hematol. 2017;96:1227–1229. doi: 10.1007/s00277-017-3020-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]