Abstract

Importance

Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in conjunction with MRI–transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) fusion-guided biopsies have improved the detection of prostate cancer. It is unclear whether MRI itself adds additional value to multivariable prediction models based on clinical parameters.

Objective

To determine whether an MRI-based prediction model can reduce unnecessary biopsies in patients with suspected prostate cancer.

Design, Setting, and Participants

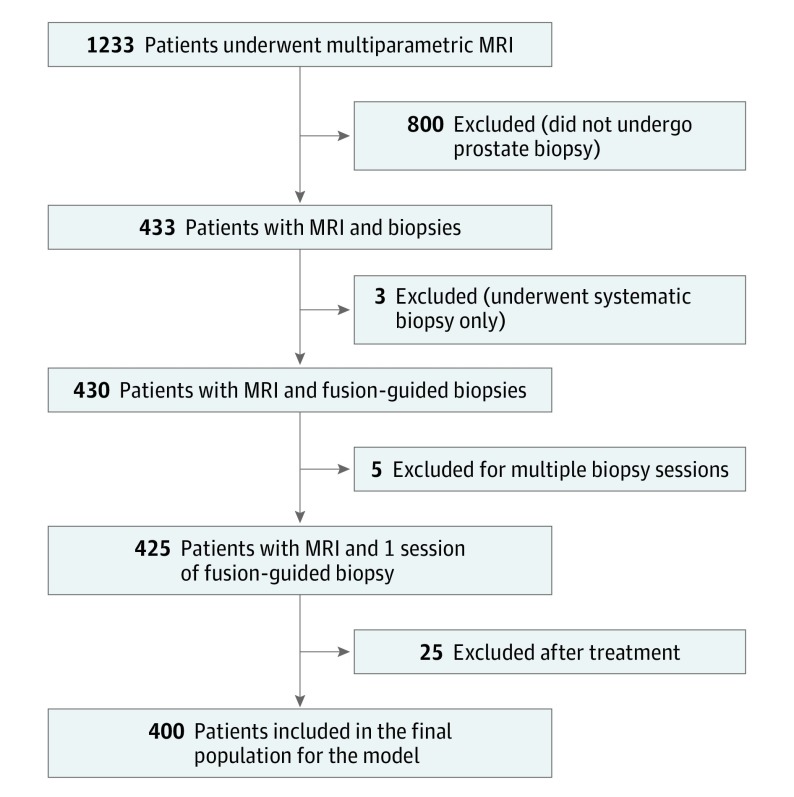

Patients underwent MRI, MRI-TRUS fusion-guided biopsy, and 12-core systematic biopsy in 1 session. The development cohort used to derive the prediction model consisted of 400 patients from 1 institution enrolled between May 14, 2015, and August 31, 2016, and the validation cohort included 251 patients from 2 independent institutions who underwent biopsies between April 1, 2013, and June 30, 2016, at 1 institution and between July 1, 2015, and October 31, 2016, at the other institution. The MRI model included MRI-derived parameters in addition to clinical variables. Area under the curve of receiver operating characteristic curves and decision curve analysis were performed.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Risk of clinically significant prostate cancer on biopsy, defined as a Gleason score of 3 + 4 or higher in at least 1 biopsy core.

Results

Overall, 193 (48.3%) of the 400 patients in the development cohort (mean [SD] age at biopsy, 64.3 [7.1] years) and 96 (38.2%) of the 251 patients in the validation cohort (mean [SD] age at biopsy, 64.9 [7.2] years) had clinically significant prostate cancer, defined as a Gleason score greater than or equal to 3 + 4. By applying the model to the external validation cohort, the area under the curve increased from 64% to 84% compared with the baseline model (P < .001). At a risk threshold of 20%, the MRI model had a lower false-positive rate than the baseline model (46% [95% CI, 32%-66%] vs 92% [95% CI, 70%-100%]), with only a small reduction in the true-positive rate (89% [95% CI, 85%-96%] vs 99% [95% CI, 89%-100%]). Eighteen of 100 fewer biopsies could have been performed, with no increase in the number of patients with missed clinically significant prostate cancers.

Conclusions and Relevance

The inclusion of MRI-derived parameters in a risk model could reduce the number of unnecessary biopsies while maintaining a high rate of diagnosis of clinically significant prostate cancers.

This cohort study examines whether a magnetic resonance imaging–based prediction model can reduce unnecessary biopsies in patients with suspected prostate cancer.

Key Points

Question

How can patients with positive findings on prostate magnetic resonance imaging who would benefit from a prostate biopsy be differentiated from those who would not benefit?

Findings

In this cohort study, a prediction model based on clinical and magnetic resonance imaging parameters was first developed in 400 patients and subsequently validated in 2 independent populations of 251 patients. The model reduced the number of unnecessary prostate biopsies while still detecting most clinically significant prostate cancers.

Meaning

This model improved risk stratification among patients with positive findings on prostate magnetic resonance imaging and can be applied to other independent patient populations; further prospective validation is justified.

Introduction

Transrectal systematic biopsy remains the standard of care for diagnosing prostate cancer. Use of this biopsy has led to an increased detection of low-grade cancers, which can result in overtreatment.1,2 Although prostate biopsy is generally considered safe, there has been an increase in biopsy-related septic complications owing to a rising prevalence of fluoroquinolone-resistant bacterial infections.3 Thus, it would be desirable to reduce the biopsy rate in men who ultimately prove to have benign conditions or low-grade disease. Current guidelines endorse the application of validated risk calculators to determine the risk of a positive prostate biopsy.4 In addition, new serum-based and urine-based biomarkers have become available to reduce unnecessary biopsy. Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the prostate in conjunction with MRI-transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) fusion-guided biopsy could also serve as a biomarker to avoid biopsy in low-risk patients.5 However, an important limitation of MRI is its variability among readers.6 To promote standardization, the Prostate Imaging-Reporting and Data System version 2 (PI-RADSv2)7 was introduced in 2015 for reporting multiparametric MRI scans. We hypothesized that a risk prediction model incorporating MRI-derived prostate volumes and PI-RADSv2 categories as variables in addition to conventional clinical predictors could reduce unnecessary prostate biopsies compared with a model based solely on clinical predictors. We test a model based on 1 institution’s data and test it against data from 2 different institutions.

Methods

Study Population for Model Development

Patients were enrolled at Institution 1 (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Maryland) between May 14, 2015, and August 31, 2016, as part of an ongoing prospective trial8 with approval from the National Institutes of Health Institutional Review Board and written informed consent. Patients with elevated serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels or abnormal results of a digital rectal examination and at least 1 lesion detected on results of multiparametric MRI were included. Exclusion criteria were having negative MRI results, nondiagnostic MRI results owing to artifacts (eg, excess patient motion or metallic prosthesis–related artifacts), prior treatment for prostate cancer (radical prostatectomy, external beam radiotherapy, brachytherapy, focal therapy, or androgen deprivation therapy), or other forms of local treatment (transurethral resection of prostate or bladder instillation therapy). For patients with multiple biopsy sessions, only the first session was included in our analysis (Figure 1). All detected lesions were evaluated and assigned a category based on the PI-RADSv2 guideline.7 Prostate Imaging-Reporting and Data System version 2 category 3 or higher lesions routinely underwent MRI-TRUS fusion-guided biopsy, while category 1 and 2 lesions were targeted only under certain circumstances or based on patient preference. Only the category of the index lesion was considered in this study and was defined by the highest PI-RADSv2 category in the prostate gland. In the case of multiple lesions with the same highest PI-RADSv2 category, the lesion with the largest size or greatest risk for extraprostatic extension was considered to be the index lesion.

Figure 1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for the Development Cohort.

MRI indicates magnetic resonance imaging.

Study Population for Model Validation

The validation population consisted of patients from 2 independent institutions (Institution 2: University of Chicago Medical Center; Institution 3: University of Alabama at Birmingham) using the same criteria as Institution 1. All patients underwent multiparametric MRI, and lesions were assigned PI-RADSv2 categories. The same definitions for index lesions and biopsy decision rules were applied as in the development cohort. Patients from Institution 2 underwent biopsies between April 1, 2013, and June 30, 2016, and PI-RADSv2 categories were assigned retrospectively. Patients from Institution 3 underwent biopsies between July 1, 2015, and October 31, 2016, and PI-RADSv2 categories were assigned prospectively.

MRI Technique and Evaluation

Imaging parameters of all 3 institutions are summarized in eTables 1-3 in the Supplement. Most imaging was performed with a 16-channel surface coil (SENSE, Philips Healthcare) and an endorectal coil (BPX-30, Medrad). In a small number of patients, the endorectal coil was omitted and a 32-channel cardiac coil (SENSE, InVivo) was used. Prostate volume was measured by a semiautomated segmentation tool (Dynacad, In Vivo). At Institution 1, all examinations were interpreted by 1 highly experienced radiologist (B.T.) with 9 years of experience in prostate cancer imaging. Scans from Institution 2 were read by 1 highly experienced radiologist (A.O.) with 12 years of experience in genitourinary imaging. Scans from Institution 3 were all reviewed in the setting of a multidisciplinary prostate imaging conference for consensus reading and PI-RADSv2 assignment based on interpretation by any of 5 fellowship-trained radiologists (J.V.T.) and 2 urologic oncologists (S.R.-B. and J.W.N.) with prostate cancer imaging experience.

Biopsy Procedure

Patients from all 3 institutions underwent MRI-TRUS fusion-guided biopsies using the office-based UroNav platform (Philips, InVivo) and an 18 × 25-cm spring-loaded core needle biopsy instrument (Bard Max-Core, Bard Biopsy Systems). All detected lesions were labeled on the T2-weighted sequence by the readers. During the procedure, the image of the prostate was segmented and coregistered with real-time TRUS. Each lesion was biopsied with at least 2 biopsy cores per lesion, as previously recommended.9 After obtaining the targeted biopsies, a 12-core systematic biopsy was performed. Biopsy specimens were evaluated and Gleason scores were assigned by 1 genitourinary pathologist per center (J.B.G. and M.J.M.), who was blinded to the results of the MRI. From each included lesion, the specimen with the highest Gleason score was considered for the model. All Gleason scores were assigned in concordance with the 2014 International Society of Urological Pathology consensus guideline.10

Model Design

The baseline model included the same clinical predictor variables as 2 commonly used risk calculators consisting of age (years), African American ethnicity (yes or no, anamnestically evaluated), prior negative biopsy (yes or no), abnormal results of digital rectal examination (yes or no), and PSA (ng/mL [to convert to micrograms per liter, multiply by 1.0]).11,12 The MRI model included all these predictors plus MRI-derived prostate volume (mL) and PI-RADSv2 category as a categorical variable (≤2, 3, 4, or 5), with PI-RADSv2 category 2 or less as reference. The outcome was risk of clinically significant prostate cancer on biopsy, defined as a Gleason score of 3 + 4 or higher in at least 1 biopsy core as a binary variable (yes or no).

Statistical Analysis

Data acquisition and reporting were consistent with the Standards of Reporting for MRI-targeted Biopsy Studies (START) of the recommendations for the prostate.13 Two multivariable logistic regression models were developed and validated to predict the risk of clinically significant prostate cancer. To improve the fit of the models to the observed data, PSA and prostate volume were transformed using the natural logarithm logPSA and logprostate volume. In the MRI model, PSA and prostate volume were expressed in terms of logPSA density and logprostate volume. The risk models were recalibrated in the validation cohort by fitting a simple intercept-slope logistic regression to the logit of predicted risks.14,15 A calibration slope near 1 reflects proper fit of the model.

Diagnostic accuracies of the 2 models were measured and compared by area under the curve (AUC) of the receiver operating characteristic curve. Model fit was assessed by calibration plot.14,15 Prediction accuracy was evaluated by the true-positive rate (TPR) and false-positive rate (FPR), where TPR is the proportion of patients above a risk threshold among those with clinically significant prostate cancer, and FPR is the proportion of patients above the same threshold among those without clinically significant prostate cancer. Clinical utility of the model was measured by the proportion of avoided biopsies, net benefit, and net reduction in the number of false-positives.16

We calculated 95% CIs and SEs of the prediction performance estimators in each model and differences between the 2 models from 2000 bootstrap samples by randomly sampling patients with replacement. For the development cohort, the prediction models were refitted, and predicted risk of each model was recalculated in each bootstrap sample. The 95% CIs were obtained from the 2.5% and 97.5% percentiles of the bootstrap resampling distribution. For the validation cohort, the data used for the bootstrap resampling procedure consisted of disease status (presence or absence of clinically significant prostate cancer) and uncalibrated predicted risk calculated from each risk prediction model. In each bootstrap sample, a simple logistic regression model for recalibration was refitted, and calibrated predicted risk was recalculated. Distributions of study variables between the development and combined validation cohort were compared by the χ2 test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon test for continuous variables. All tests were 2-sided, and P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study Populations

A total of 400 prospectively accrued consecutive patients met the inclusion criteria and were included in the development of the model. The external validation cohort consisted of 251 patients, 101 from Institution 2 and 150 from Institution 3. Patient demographics of all 3 cohorts are summarized in Table 1. The prevalence of clinically significant prostate cancer was 48.3% (n = 193) in the development cohort (mean [SD] age at biopsy, 64.3 [7.1] years) and 38.2% (n = 96) in the combined validation cohort (mean [SD] age at biopsy, 64.9 [7.2] years).

Table 1. Patient Demographics of Development and Validation Cohorts.

| Variable | Development Cohort: Institution 1 (n = 400) | Validation Cohort | P Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Institution 2 (n = 101) | Institution 3 (n = 150) | |||

| Age at biopsy, mean (SD), y | 64.3 (7.1) | 64 (8.0) | 64.9 (7.2) | .84 |

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | ||||

| White | 321 (80.3) | 90 (89.1) | 121 (80.7) | .47 |

| African American | 53 (13.3) | 11 (10.9) | 29 (19.3) | |

| Asian | 15 (3.8) | 0 | 0 | |

| Hispanic | 3 (0.8) | 0 | 0 | |

| Family history of prostate cancer, No. (%) | ||||

| Yes | 95 (23.8) | 29 (28.7) | 33 (22.0) | .83 |

| No | 305 (76.3) | 72 (71.3) | 117 (78.0) | |

| Prior negative prostate biopsy results, No. (%) | ||||

| Yes | 221 (55.3) | 27 (26.7) | 68 (45.3) | <.001 |

| No | 179 (44.8) | 73 (72.3) | 82 (54.7) | |

| Unknown | NA | 1 (1.0) | NA | |

| DRE results, No. (%) | ||||

| Positive | 49 (12.3) | 11 (10.9) | 7 (4.7) | .05 |

| Negative | 351 (87.8) | 90 (89.1) | 143 (95.3) | |

| PSA, median (IQR), ng/mL | 6.6 (4.7-9.5) | 6.2 (4.7-8.9) | 6 (4.5-9.1) | .15 |

| Prostate volume, median (IQR), mL | 55 (41.2-78.0) | 42 (28.5-61.0) | 44.3 (33.6-64.5) | <.001 |

| PSA density, median (IQR), ng/mL/mL | 0.11 (0.08-0.17) | 0.13 (0.10-0.21) | 0.13 (0.08-0.23) | .003 |

| PI-RADSv2 category, No. (%) | ||||

| 1 | 1 (0.3) | 23 (22.8) | 0 | <.001 |

| 2 | 32 (8.0) | 11 (10.9) | 5 (3.3) | |

| 3 | 53 (13.3) | 17 (16.8) | 42 (28.0) | |

| 4 | 182 (45.5) | 26 (25.7) | 67 (44.7) | |

| 5 | 132 (33.0) | 24 (23.8) | 36 (24.0) | |

| Gleason score, No. (%) | ||||

| No cancer | 128 (32.0) | 32 (31.7) | 50 (33.3) | .006 |

| 3 + 3 | 79 (19.8) | 27 (26.7) | 46 (30.7) | |

| 3 + 4 | 107 (26.8) | 33 (32.7) | 23 (15.3) | |

| 4 + 3 | 36 (9.0) | 5 (5.0) | 17 (11.3) | |

| 8 | 41 (10.3) | 3 (3.0) | 6 (4.0) | |

| 9-10 | 9 (2.3) | 1 (1.0) | 8 (5.3) | |

Abbreviations: DRE, digital rectal examination; IQR, interquartile range; NA, not applicable; PI-RADSv2, Prostate Imaging-Reporting and Data System version 2; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; Validation Cohort Institution 2, University of Chicago Medical Center; Validation Cohort Institution 3, University of Alabama at Birmingham.

SI conversion factor: To convert PSA to micrograms per liter, multiply by 1.0.

Comparison between development and combined validation cohorts.

The development cohort had a similar mean age, family history, race/ethnicity, and median PSA profile compared with the validation cohort but had significantly lower median PSA density, lower proportion of PI-RADSv2 categories 3 and 4, and a higher proportion of positive results of digital rectal examinations, prior negative prostate biopsies, and PI-RADSv2 category 5.

Prediction Model Development

All the clinical variables were independent predictors in the multivariate baseline model, and, except for positive results of digital rectal examinations, they remained statistically significant in the MRI model (Table 2). The risk for clinically significant prostate cancer was inversely associated with prostate volume and increased with PSA density and PI-RADSv2 category. The calibration plot demonstrated superior fit of the MRI model compared with the baseline model in both the development cohort and validation cohort (eFigures 1 and 2 in the Supplement).

Table 2. Logistic Regression Prediction Models of Clinically Significant Prostate Cancer for the Development Cohort.

| Characteristic | Baseline Model | P Value | MRI Model | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | OR (95% CI) | Coefficient | OR (95% CI) | |||

| Intercept | −2.44 | NA | .02 | 2.38 | NA | .14 |

| Age at biopsy, y | 0.04 | 1.04 (1.01-1.07) | .02 | 0.05 | 1.05 (1.01-1.09) | .009 |

| African American race/ethnicity, yes | 1.10 | 3.03 (1.54-5.88) | .001 | 1.10 | 3.03 (1.39-6.67) | .005 |

| Prior negative prostate biopsy results, yes | −1.20 | 0.30 (0.19-0.47) | <.001 | −1.12 | 0.33 (0.19-0.56) | <.001 |

| Abnormal DRE results, yes | 0.70 | 2.02 (1.02-4.01) | .04 | 0.40 | 1.49 (0.66-3.38) | .34 |

| Log (PSA), ng/mL | 0.82 | 2.27 (1.54-3.34) | <.001 | NA | NA | NA |

| Log (prostate volume), mL | NA | NA | NA | −0.78 | 0.46 (0.24-0.88) | .02 |

| Log (PSA density), ng/mL/mL | NA | NA | NA | 0.94 | 2.55 (1.57-4.15) | <.001 |

| PI-RADSv2 category | ||||||

| 1 + 2 | NA | NA | NA | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | <.001 |

| 3 | NA | NA | NA | 0.4 | 1.49 (0.46-4.84) | |

| 4 | NA | NA | NA | 0.86 | 2.37 (0.88-6.36) | |

| 5 | NA | NA | NA | 2.48 | 11.9 (4.11-34.96) | |

Abbreviations: DRE, digital rectal examination; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio; PI-RADSv2, Prostate Imaging-Reporting and Data System version 2; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

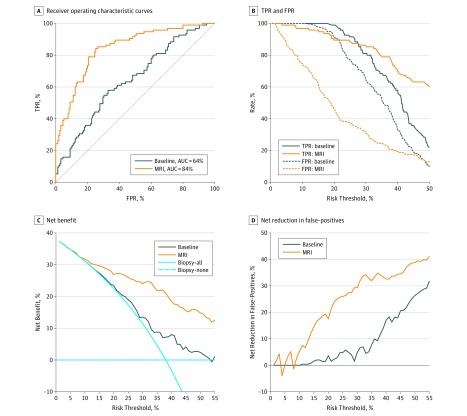

Compared with the baseline model, AUC increased from 72% to 84% (P < .001) in the MRI model in the development cohort (eFigure 3A and eTable 4 in the Supplement). In the validation cohort, compared with the baseline model, AUC increased from 64% to 84% (P < .001) (Table 3 and Figure 2A).

Table 3. Performance of the 2 Risk Prediction Models in the Validation Cohort.

| Performance Parameter | Risk Threshold, % | Model | Comparison | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | MRI | MRI vs Baseline | ||

| AUC (95% CI) | NA | 64 (57-71) | 84 (79-89) | 20 (14 to 27)a |

| TPR, % (95% CI) | 10 | 100 (100-100) | 97 (93-100) | −3 (−7 to 0) |

| 15 | 100 (96-100) | 96 (90-98) | −4 (−9 to −1) | |

| 20 | 99 (89-100) | 89 (85-96) | −9 (−13 to 2) | |

| FPR, % (95% CI) | 10 | 100 (95-100) | 74 (58-87) | −26 (−40 to −13) |

| 15 | 97 (84-100) | 62 (41-77) | −35 (−52 to −21) | |

| 20 | 92 (70-100) | 46 (32-66) | −46 (−59 to −27) | |

| NB, % (95% CI) | 10 | 31 (24-38) | 32 (25-38) | 1 (−1 to 2) |

| 15 | 27 (20-34) | 30 (23-36) | 2 (0 to 5) | |

| 20 | 23 (16-30) | 27 (21-34) | 4 (1 to 8) | |

| NRFP, % (95% CI) | 10 | 0 (0-3) | 5 (8-20) | 5 (−9 to 19) |

| 15 | 2 (1-6) | 15 (0-27) | 13 (−1 to 26) | |

| 20 | 4 (2-10) | 18 (7-33) | 14 (4 to 31) | |

| PAB, % (95% CI) | 10 | 0 (0-3) | 17 (9-28) | 17 (9 to 27) |

| 15 | 2 (0-12) | 25 (16-41) | 24 (14 to 36) | |

| 20 | 6 (0-24) | 38 (22-48) | 32 (18 to 40) | |

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; FPR, false-positive rate; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NA, not applicable; NB, net benefit; NRFP, net reduction in false-positives; PAB, percentage of avoided biopsies; TPR, true-positive rate.

P < .001 for the comparison of AUCs.

Figure 2. Plot of Performance Metrics of the Validation Cohort.

A, Receiver operating characteristic curves or risk prediction models for clinically significant prostate cancer. B, True-positive rate (TPR) and false-positive rate (FPR). C, Net benefit. D, Net reduction in false-positive results from the 2 risk prediction models. AUC indicates area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

The TPR and FPR of both models are shown in eTable 4 and eFigure 3B in the Supplement for the development cohort. The TPR and FPR of the calibrated risk models (eTable 5 in the Supplement) are displayed in Table 3 and Figure 2B for the validation cohort. The MRI model had lower FPR than the baseline model, with a minimal loss of TPR.

Decision Curve Analysis

Net benefits and net reduction in the number of false-positives are shown in eFigure 3C and D in the Supplement for the development cohort and in Figure 2C and D for the validation cohort. By applying the MRI model to the validation cohort, higher net benefit and net reduction in the number of false-positives than the baseline model and the strategy of conducting a biopsy for every patient (biopsy-all) could be achieved for risk thresholds above 10%. For example, at the 20% risk cutoff, the net benefit was 23% (95% CI, 15%-30%) in the treat-all model, 23% (95% CI, 16%-30%) in the baseline model, and 27% (95% CI, 21%-34%) in the MRI model, and net reduction in the number of false-positives was 0% in the treat-all model, 4% (95% CI, –2% to 10%) in the baseline model, and 18% (95% CI, 7%-33%) in the MRI model. The net benefit of the MRI model was equivalent to performing 27 biopsies per 100 men without negative biopsies, 4 more than the baseline model. The net reduction in the number of false-positives based on the MRI model, compared with having to perform a biopsy in all patients with positive MRI results, was equivalent to performing 18 fewer unnecessary biopsies per 100 men, with no increase in the number of clinically significant prostate cancer left undiagnosed. Overall, 38% (95% CI, 22%-48%) of biopsies could have been avoided compared with 6% (95% CI, 0%-24%) of biopsies avoided by the baseline model at this threshold.

Discussion

When MRI was incorporated into a prediction model, it exhibited improved model fit and superior diagnostic accuracy, reducing unnecessary biopsies while maintaining a similar level of sensitivity for high-risk cancers compared with the baseline model. Although the prediction model was developed at 1 institution using 1 set of physicians, it demonstrated general applicability by confirmation in a validation cohort of 251 patients from 2 independent centers. In clinical practice, the threshold for biopsy should be decided after a physician and patient both weigh the relative harm of potentially unnecessary biopsy and benefit of diagnosing clinically significant prostate cancer. Therefore, there is not a single risk threshold that is used to determine who needs to undergo biopsy but rather a range of risk thresholds. For instance, by choosing a risk threshold of 20%, a total of 38% of biopsies could have been avoided while still identifying 89% of clinically significant cancers. In this validation cohort, 96 of 251 patients (38.2%) would have been spared a biopsy while 11 of 96 patients with clinically significant disease (11.5%) would have been missed.

It has become more common that the results of multiparametric MRI are used to guide clinical decision making on prostate biopsy. Recently, Ahmed et al17 published the results of a large multicenter study of 740 patients in the United Kingdom. Using multiparametric MRI with a 5-point Likert score, 27% of patients could have avoided a biopsy, while the use of MRI resulted in 18% more cases of clinically significant prostate cancer (defined as a Gleason score ≥4+3 = 7, or a maximum cancer core length ≥6 mm) being detected. However, no generalizable clinical prediction models were implemented in this analysis; therefore, there is no comparison with how MRI can improve clinical practice. Furthermore, the study used 5-mm template prostate mapping biopsy rather than image-guided biopsy as a reference test. Although template biopsies are more appropriate to assess tumor burden compared with transrectal systematic biopsies, template biopsies are too complex and invasive, which inhibits their applicability in clinical practice. Contrary to the study by Ahmed et al,17 lesions in our study were biopsied with an MRI-TRUS fusion-guided system, which can be performed under local anesthesia in an office-based setting as done in our study. Another limitation of the study by Ahmed et al17 was that it relied on a 5-point Likert scale rather than the standardized PI-RADSv2 scale. As the Likert scale is not widely used, it may be difficult to replicate.

Several prediction models incorporating MRI have been proposed. Radtke et al18 created a multivariate prediction model in 1159 patients who underwent MRI-TRUS fusion-guided biopsy and transperineal template biopsy. The same clinical and imaging-based predictors were used as in our current study. The prediction model demonstrated an AUC of 83% in biopsy-naïve patients and 81% in patients after previous biopsies. Beyond the 10% threshold, the model in the study by Radtke et al18 showed greater net benefit compared with the biopsy-all strategy and a reduction of unnecessary biopsies. However, their main limitation was the lack of external validation of the model, which is an important step before a model can be applicable in clinical practice. Our model performed well in an external cohort despite differing clinical characteristics compared with the training cohort. In addition, the analysis of Radtke et al18 was based on version 1 of the PI-RADS guideline instead of the currently used version 2.

Van Leeuwen et al19 also developed a multiparametric MRI-based prediction model, which was based on 393 patients and externally validated in 198 men. Their model had the highest AUC (88.3%) when compared with a PSA and PSA-clinical–based model. Their decision curve analysis revealed that, at thresholds between 2.5% and 15%, a total of 10.7% to 37.9% of biopsies could have been avoided while missing 0% to 7.4% of cases with clinically significant disease compared with the biopsy-all strategy. However, their model was not able to provide benefit to their validation cohort; while the validation cohort had a higher rate of clinically significant disease, their model underpredicted the risk. In addition, their biopsy data were based mostly on transperineal template biopsy and only in some cases on fusion-guided biopsy. Finally, version 1 of PI-RADS was also used instead of the current PI-RADSv2 used in our study.

Limitations

The model we propose produces results comparable with those previously reported. However, there are several caveats. First, only patients with MRI-detected lesions underwent MRI-TRUS fusion-guided biopsies. Patients with negative MRI results did not routinely undergo biopsies. This factor could contribute to verification bias.20 It is, however, well known that the likelihood of clinically significant prostate cancer in patients with negative results of multiparametric MRI is low.21 Thus, on one hand, patients with negative MRI results are unlikely to benefit from a biopsy. Our model, on the other hand, can help identify patients who are likely to benefit from a biopsy. Second, the data on pathologic findings used in the model are based on systematic and MRI-TRUS fusion-guided biopsy data, which can potentially underestimate the real tumor burden. However, MRI-TRUS fusion-guided biopsy pathologic findings have a higher concordance with radical prostatectomy histopathologic findings than systematic biopsy.5 Studies with whole-mount pathologic specimens as the reference standard are subject to selection bias because such populations are dominated by patients with intermediate or high-risk prostate cancer who are nevertheless in sufficiently good health to undergo surgery. Template mapping biopsy is a potential alternative to the use of radical prostatectomy specimens, but its use in clinical practice is limited by practical issues. Finally, our sample size of 400 patients in the development set is small compared with established prediction tools based on large prospective randomized trials with several thousand patients.11 However, the power of a study is driven by the number of events, not simply by the total number of patients.22 With a prevalence of 48% of patients with clinically significant prostate cancer in our development cohort, the size of our study was adequate to power a comparison of the 2 risk prediction models that were assessed.

Conclusions

Our MRI-based risk calculator incorporating prostate volume and PI-RADSv2 score can be used to reduce the number of unnecessary prostate biopsies in patients who are unlikely to harbor clinically significant prostate cancer while capturing most of the patients with clinically significant prostate cancer. The successful validation in 2 independent external cohorts justifies its use in other external centers for prospective validation.

eFigure 1. Calibration Plot of Mean Predicted Risk and the 95% CI vs Observed Proportion of Clinically Significant Prostate Cancer in Each Decile of Adjusted Risk Scores of the Development Cohort

eFigure 2. Calibration Plot of Mean Predicted Risk and the 95% CI vs Observed Proportion of Clinically Significant Prostate Cancer in Each Decile of Calibrated Risk Scores of the Validation Cohort

eFigure 3. Plot of Performance Metrics of the Development Cohort

eTable 1. MRI Imaging Parameters of Institution 1

eTable 2. MRI Imaging Parameters of Institution 2

eTable 3. MRI Imaging Parameters of Institution 3

eTable 4. Calibration in the Large and Calibration Slope of the Predicted Risks in the Validation Cohort

eTable 5. Performance of the Two Risk Prediction Models in the Development Cohort

References

- 1.Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, et al. ; ERSPC Investigators . Screening and prostate-cancer mortality in a randomized European study. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(13):1320-1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(1):7-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borghesi M, Ahmed H, Nam R, et al. Complications after systematic, random, and image-guided prostate biopsy. Eur Urol. 2017;71(3):353-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mottet N, Bellmunt J, Bolla M, et al. EAU-ESTRO-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer, part 1: screening, diagnosis, and local treatment with curative intent. Eur Urol. 2017;71(4):618-629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siddiqui MM, Rais-Bahrami S, Turkbey B, et al. Comparison of MR/ultrasound fusion-guided biopsy with ultrasound-guided biopsy for the diagnosis of prostate cancer. JAMA. 2015;313(4):390-397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenkrantz AB, Lim RP, Haghighi M, Somberg MB, Babb JS, Taneja SS. Comparison of interreader reproducibility of the Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System and Likert scales for evaluation of multiparametric prostate MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;201(4):W612-W618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.PI-RADS ACR. Prostate Imaging and Reporting and Data System 2015. Version 2 Reston, Virgina: American College of Radiology; 2015.

- 8.ClinicalTrials.gov Use of Tracking Devices to Locate Abnormalities During Invasive Procedures. NCT00102544. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00102544 Accessed August 8, 2017.

- 9.Hong CW, Rais-Bahrami S, Walton-Diaz A, et al. Comparison of magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound (MRI-US) fusion-guided prostate biopsies obtained from axial and sagittal approaches. BJU Int. 2015;115(5):772-779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Epstein JI, Egevad L, Amin MB, Delahunt B, Srigley JR, Humphrey PA; Grading Committee . The 2014 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) consensus conference on Gleason grading of prostatic carcinoma: definition of grading patterns and proposal for a new grading system. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40(2):244-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson IM, Ankerst DP, Chi C, et al. Assessing prostate cancer risk: results from the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(8):529-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kranse R, Roobol M, Schröder FH. A graphical device to represent the outcomes of a logistic regression analysis. Prostate. 2008;68(15):1674-1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore CM, Kasivisvanathan V, Eggener S, et al. ; START Consortium . Standards of reporting for MRI-targeted biopsy studies (START) of the prostate: recommendations from an International Working Group. Eur Urol. 2013;64(4):544-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steyerberg EW, Vickers AJ, Cook NR, et al. Assessing the performance of prediction models: a framework for traditional and novel measures. Epidemiology. 2010;21(1):128-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pepe M, Janes H. Lecture notes in statistics In: Lee M-LT, Gail M, Pfeiffer R, Satten G, Cai T, Gandy A, eds. Risk Assessment and Evaluation of Predictions. Vol 215 New York, NY: Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vickers AJ, Elkin EB. Decision curve analysis: a novel method for evaluating prediction models. Med Decis Making. 2006;26(6):565-574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmed HU, El-Shater Bosaily A, Brown LC, et al. ; PROMIS Study Group . Diagnostic accuracy of multi-parametric MRI and TRUS biopsy in prostate cancer (PROMIS): a paired validating confirmatory study. Lancet. 2017;389(10071):815-822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Radtke JP, Wiesenfarth M, Kesch C, et al. Combined clinical parameters and multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging for advanced risk modeling of prostate cancer—patient-tailored risk stratification can reduce unnecessary biopsies. Eur Urol. 2017;72(6):888-896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Leeuwen PJ, Hayen A, Thompson JE, et al. A multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging–based risk model to determine the risk of significant prostate cancer prior to biopsy. BJU Int. 2017;120(6):774-781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tangen CM, Goodman PJ, Till C, Schenk JM, Lucia MS, Thompson IM Jr. Biases in recommendations for and acceptance of prostate biopsy significantly affect assessment of prostate cancer risk factors: results from two large randomized clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(36):4338-4344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moldovan PC, Van den Broeck T, Sylvester R, et al. What is the negative predictive value of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging in excluding prostate cancer at biopsy? a systematic review and meta-analysis from the European Association of Urology Prostate Cancer Guidelines Panel. Eur Urol. 2017;72(2):250-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Altman DG, McShane LM, Sauerbrei W, Taube SE. Reporting Recommendations for Tumor Marker Prognostic Studies (REMARK): explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2012;9(5):e1001216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Calibration Plot of Mean Predicted Risk and the 95% CI vs Observed Proportion of Clinically Significant Prostate Cancer in Each Decile of Adjusted Risk Scores of the Development Cohort

eFigure 2. Calibration Plot of Mean Predicted Risk and the 95% CI vs Observed Proportion of Clinically Significant Prostate Cancer in Each Decile of Calibrated Risk Scores of the Validation Cohort

eFigure 3. Plot of Performance Metrics of the Development Cohort

eTable 1. MRI Imaging Parameters of Institution 1

eTable 2. MRI Imaging Parameters of Institution 2

eTable 3. MRI Imaging Parameters of Institution 3

eTable 4. Calibration in the Large and Calibration Slope of the Predicted Risks in the Validation Cohort

eTable 5. Performance of the Two Risk Prediction Models in the Development Cohort