Abstract

Importance

Firearm laws in one state may be associated with increased firearm death rates from homicide and suicide in neighboring states.

Objective

To determine whether counties located closer to states with lenient firearm policies have higher firearm death rates.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional study of firearm death rates by county for January 2010 to December 2014 examined data from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for firearm suicide and homicide decedents for 3108 counties in the 48 contiguous states of the United States.

Exposures

Each county was assigned 2 scores, a state policy score (range, 0-12) based on the strength of its state firearm laws, and an interstate policy score (range, −1.33 to 8.31) based on the sum of population-weighted and distance-decayed policy scores for all other states. Counties were divided into those with low, medium, and high home state and interstate policy scores.

Main Outcomes and Measures

County-level rates of firearm, nonfirearm, and total homicide and suicide. With multilevel Bayesian spatial Poisson models, we generated incidence rate ratios (IRR) comparing incidence rates between each group of counties and the reference group, counties with high home state and high interstate policy scores.

Results

Stronger firearm laws in a state were associated with lower firearm suicide rates and lower overall suicide rates regardless of the strength of the other states’ laws. Counties with low state scores had the highest rates of firearm suicide. Rates were similar across levels of interstate policy score (low: IRR, 1.34; 95% credible interval [CI], 1.11-1.65; medium: IRR, 1.36, (95% CI, 1.15-1.65; and high: IRR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.20-1.73). Counties with low state and low or medium interstate policy scores had the highest rates of firearm homicide. Counties with low home state and interstate scores had higher firearm homicide rates (IRR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.02-1.88) and overall homicide rates (IRR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.03-1.67). Counties in states with low firearm policy scores had lower rates of firearm homicide only if the interstate firearm policy score was high.

Conclusions and Relevance

Strong state firearm policies were associated with lower suicide rates regardless of other states’ laws. Strong policies were associated with lower homicide rates, and strong interstate policies were also associated with lower homicide rates, where home state policies were permissive. Strengthening state firearm policies may prevent firearm suicide and homicide, with benefits that may extend beyond state lines.

This cross-sectional analysis of US county data examines whether counties in states located closer to states with lenient firearm policies have higher firearm death rates.

Key Points

Question

Are state firearm laws associated with increases in interstate firearm deaths from homicide and suicide?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study, strong firearm laws in a state were associated with lower firearm suicide rates and lower overall suicide rates in the state regardless of the strength of the laws in other states. Strong firearm laws in a state were associated with lower rates of firearm homicide. Counties in states with weak laws had lower rates of firearm homicide only when surrounding states had strong laws.

Meaning

Strengthening firearm policies at the state level could help to reduce the incidence of both firearm suicide and homicide, with benefits that extend across state lines.

Introduction

Firearm injuries caused 36 252 deaths in the United States in 2015, including 22 018 (60.7%) from suicides and 12 979 (35.8%) from homicides. Despite decreases in violent deaths in the 1990s, the rate of deaths from firearm injuries remained steady from 1999 through 2015, with an increase in the firearm suicide rate from 5.96 to 6.48 per 100 000 population in the same period.1,2 Firearms account for over 50% of suicides and two-thirds of homicides,3 and firearm injuries and deaths are an important public health issue.4,5,6,7,8,9,10

States regulate how firearms are bought, sold, and tracked, as well as who may purchase them.11,12 Stronger firearm policy environments have been associated with lower rates of firearm deaths,12,13,14 as have specific laws, such as licensing and inspection of firearm dealers,15,16 licensing and background checks for handgun sales,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23 including private sales24,25 and laws regulating the availability of inexpensive handguns.18 Laws, however, vary widely among states, and evidence of their impact is limited.7,26,27

Firearms may move across state lines, presenting a challenge to effective state policies. Evidence from Federal Bureau of Investigation firearm traces indicates that in states with strict firearm laws, many crimes are committed using firearms that originated out-of-state.28,29 To investigate the effect of home state and out-of-state firearm laws on firearm death rates, we conducted a cross-sectional study of firearm deaths in United States counties from January 2010 to December 2014. We hypothesized that counties located in states with more restrictive firearm laws would have lower rates of firearm suicide and homicide, and that firearm death rates would be higher in counties near adjoining states with more lenient laws.

Methods

Study Sample

The units of analysis for this study were United States counties. We excluded counties in Alaska and Hawaii because our measure of interstate policy impact assumed that the effect of distance was uniform among localities, and travel from these noncontiguous states differs. We excluded Washington, DC, because there are no applicable state laws. Our final sample was 3108 counties in 48 states. This study received a waiver of review from the Weill Cornell Medicine institutional review board.

Dependent Measures

The dependent measures were counts of deaths for the years from January 2010 to December 2014, according to International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) classification. Using Compressed Mortality Data records from the Centers for Disease Control,30 we calculated counts of firearm homicide (ICD-10 codes U014, X93-X95), nonfirearm homicide (ICD-10 codes U011, U012, X85-X92, X96-X99, Y00-Y05, Y060-Y062, Y068-Y073, Y078, Y079, Y08, Y09, Y871), firearm suicide (ICD-10 codes X72-X74), and nonfirearm suicide (ICD-10 codes U030, X60-X71, X75-84, Y870). We calculated total homicides and suicides by summing firearm and nonfirearm deaths.

Policy Metric

The Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence (LCPGV) provided detailed data describing firearm laws for every state for 2010.11 We reviewed the literature and identified 6 categories of laws for which evidence best supports an association with firearm death or interstate movement of firearms (Table 1). Dealer practices and standards may vary between and within states, and laws mandating strict licensing requirements or increased law enforcement oversight of dealers have been associated with up to 50% lower rates of firearm homicide.15,16 We included laws requiring background checks for private sales of firearms (including gun show sales), because states with these laws have been shown to have lower rates of firearm death.12,24,25 Laws that require individuals to obtain licenses to purchase or own firearms have been associated with lower rates of death.17,22 Regulations setting minimum design standards for firearms limit the availability of inexpensive handguns (“Saturday night specials”) and have been associated with 6.8% to 11.5% fewer firearm homicides.18 Two types of laws focus on preventing diversion of legally purchased firearms to homicide and other crimes. Laws restricting multiple purchases of guns are designed to prevent “straw purchasers” from buying excess firearms on behalf of those who could not legally purchase a firearm. Twenty percent of firearms used in crime originate in multiple purchases, and these laws have been shown to reduce diversion of firearms by up to two-thirds.31,32,33 Firearms used in crime may be legally purchased but then lost or stolen. Laws requiring owners to report loss and theft have been associated with a 30% decrease in firearms diversion.24 Increased rates of firearm ownership have been associated with higher firearm suicide rates at the state level,34 and presence of firearms in the home is associated with firearm suicide risk at the individual level,35 but few studies have examined the association of firearm policies and firearm suicide. Licensing laws, however, have been associated with a 15% to 23% decrease in firearm suicide.23,36 Studies have yet to establish the efficacy of other legal strategies for preventing suicide, such as gun restraining orders.36 Based on the LCPGV methodology, we rated each state 0 to 2 in each of 6 areas, with stronger policies receiving 2 points and more lenient regulations receiving 1 point (Table 1). We summed these scores to a cumulative measure, with possible values of 0 to 12.

Table 1. Firearm Control Laws Included in the State Firearm Policy Scale.

| Law | Descriptiona | Scoring |

|---|---|---|

| Dealer regulation15,16 | Laws regulating record keeping, security practices, and licensing for firearms dealers | 1 point: Ban residential dealers, require security measures, or require reporting of sales, losses and thefts to law enforcement 2 points: Require dealer license |

| Background checks for private sales24,25 | Laws requiring background checks for firearms sales made by individuals who are not federally licensed dealers | 1 point: select firearms or only required at gun shows 2 points: required for all private sales |

| License to purchase or own17,22 | Laws that require an individual to obtain a license prior to purchasing or owning a firearm | 1 point: Require license for select firearms only, require safety training or testing, limit duration of license to ≤1 y 2 points: Require license for purchase or possession of all firearms |

| Junk gun regulation18 | Laws that require firearms to meet design and manufacturing standards | 1 point: Allow sale of only a list of approved guns 2 points: Require specific design and safety standards |

| Reporting requirement for lost or stolen guns24 | Laws that require individuals to report the loss or theft of their firearms within a specified period of time | 2 points: Require reporting of lost or stolen firearms |

| Multiple purchases31 | Laws that restrict the number of firearms an individual can purchase within a given timeframe | 2 points: restrict multiple purchases or sales |

The Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence (LCPGV) provided detailed data describing firearm laws for every state for 2010. Based on the LCPGV methodology, we rated each state 0 to 2 in each of 6 areas, with stronger policies receiving 2 points and more lenient regulations receiving 1 point. These scores were summed to a cumulative measure, with possible values of 0 to 12.

For each county, we calculated an interstate policy score. Borrowing concepts from transport geography,37 we assumed that the strength of an interstate policy association would be greatest between places located close to one another.38,39 For example, a county located in New York state adjacent to the border of Pennsylvania would be more likely to be affected by Pennsylvania laws than Vermont laws. Therefore, the interstate policy score includes an inverse-distance decay term. We assumed a state with a larger population would have greater potential to serve as a source of firearms, and so weighted the interstate policy score by population, consistent with established methods.37 We standardized the score with a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1, resulting in a range of scores from −1.33 to 8.31, with higher scores indicating stricter laws in nearby states. Further details about the interstate policy score are available eMethods in the Supplement.

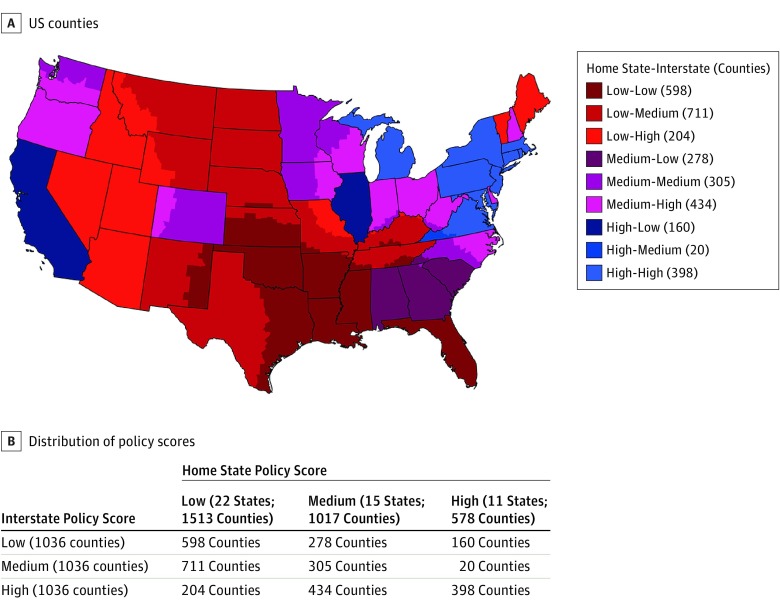

To understand the combined influence of home state and interstate policy scores, we divided counties into 3 groups by home state policy score, with counties in the low group having 0 included state policies (22 states); those in the medium group having 1 to 2 (15 states); and those in the high group having 3 to 10 (11 states). No state had a score of more than 10 included state policies. These cutoffs were chosen to create 3 groups close to equal size. However, as more than one-third of counties had a home state policy score of 0, the groups are uneven in size. We also divided the interstate policy score for counties into tertiles of 1036 counties each. Interstate policy scores in the low tertile ranged from −1.33 to −0.46. Interstate policy scores in the medium tertile ranged from −0.46 to −0.01. Interstate policy scores in the high tertile ranged from −0.01 to 8.31. Considered together, these variables yielded a primary exposure variable with 9 categories encompassing both exposures (Figure).

Figure. Geographic Distributions of Combined Home State and Interstate Policy Scores.

A, Map of US counties showing home state and interstate policy scores. B, Distribution of US counties into low, medium, and high home state and interstate policy scores.

Covariates

We used 5-year estimates from the American Community Survey for January 2010 to December 2014 to describe county demographic characteristics,40 including population size, median age, median household income, sex, and race/ethnicity. We included 4 measures of neighborhood disadvantage related to violence: the unemployment rate, the proportion age 25 years or older without a high school diploma, households receiving public assistance, and female-headed households.41 We controlled for rates of crimes against persons and against property using data from the Federal Bureau of Investigation Uniform Crime Reporting System.42

Statistical Analysis

Using established techniques in epidemiology, we constructed multilevel spatial Poisson models.43,44,45 A first group of models assessed relationships for homicides, and a second group of models assessed relationships for suicides. For both homicides and suicides, we conducted separate analyses for firearm deaths, nonfirearm deaths, and all deaths.

We fitted the Poisson models using a Bayesian procedure in WinBUGS v14 (University of Cambridge).46 To account for spatial autocorrelation (the concept that places closer to one another are likely more similar than those that are far apart), all models included a conditional autoregressive random effect that smoothed the effect of outliers and controlled for overdispersion of the count data. In addition, this modeling strategy accounted for unmeasured, spatially structured, regional characteristics that may cause counties in the same region to have similar policies and similar mortality rates, without requiring us to include a categorical variable to control for region explicitly (southeast vs southwest, etc) (eMethods in the Supplement).43,47 Because counties in the same state may be more similar to each other than counties in different states, models included a state-level random effect. This approach yields an incidence rate ratio (IRR), which provides an estimate of how observed death rates in each group differ from a specified reference group, for the firearm policy variable, or for a 1-unit difference in the exposure variable, such as for the demographic variables. The IRR is situated within a 95% credible interval (CI), which is analogous to a 95% confidence interval in conventional regression analyses. We performed geoprocessing using ArcGIS 10.3 (Esri Inc), and nonspatial data management using Stata v14 (StataCorp).

Sensitivity Analyses

We conducted multiple tests to minimize the likelihood that our results were artifacts of model or variable specification (eTable 1 in the Supplement). We conducted a sensitivity analysis using inverse distance squared to allow geographic relationships to fall off more quickly. We reconstructed all 6 Poisson models, replacing the dependent variables with deaths from 2010 only, to account for possible variation in trends over time between counties. We also replaced the 2010 home state and interstate policy scores with similar scores calculated using: (1) 2012 policies; (2) complete scores proposed by the LCPGV, including 35 firearm laws, rather than the 6 areas selected for our primary analysis11; and (3) scores developed using iterative principal components analyses. The principle components analysis aimed to identify correlations among all 35 laws for which the LCPGV collected data. We calculated Eigenvectors for these laws, removing laws with Eigenvectors less than 0.3 (highly correlated with other laws), and then taking a count of laws in a final analysis in which all laws had Eigenvectors greater than 0.3.48 We evaluated the home state and interstate policy variables separately, and tested an interaction between the home state and interstate policy scores as continuous variables.

Results

Table 2 shows descriptive statistics for the 3108 counties. The mean (SD) county firearm suicide rate was 10.04 (6.10) per 100 000 population per year, and the mean (SD) county firearm homicide rate was 2.56 (3.21). Geographic distributions of firearm homicide and suicide rates are presented in the eFigure in the Supplement. The Figure shows geographic distributions of combined home state policy scores and interstate policy scores. California had the strongest firearm control laws (10 out of 12). However, because California is adjacent to states with low policy scores, many California counties had low interstate policy scores.

Table 2. Characteristics of US Counties (N = 3108) Included in the Study.

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) [Range] |

|---|---|

| Deaths, average annual rate per 100 000 populationa | |

| Firearm suicides | 10.04 (6.10) [0.00 to 72.90] |

| Nonfirearm suicides | 6.05 (4.14) [0.00 to 63.08] |

| All suicides | 16.09 (7.59) [0.00 to 97.21] |

| Firearm homicides | 2.56 (3.21) [0.00 to 38.10] |

| Nonfirearm homicides | 1.50 (1.82) [0.00 to 30.63] |

| All homicides | 4.06 (4.12) [0.00 to 42.17] |

| Firearm Policy Scales, 2010 data | |

| Home state policy scale | 1.53 (2.30) [0.00 to 10.00] |

| Interstate policy scale, standardized | 0.00 (1.00) [−1.33 to 8.31] |

| Census Characteristics, 2010-2014 mean | |

| Population | 100 179.70 (321 005.30) [89.00 to 9 974 203.00] |

| Area, square miles | 990.85 (1323.11) [2.00 to 20 105.40] |

| Male, % | 50.01 (2.35) [37.36 to 71.66] |

| Median age, y | 40.75 (5.20) [21.60 to 64.50] |

| Black, % | 8.94 (14.46) [0.00 to 85.91] |

| Hispanic, % | 8.69 (13.47) [0.00 to 95.68] |

| Annual median household income, $ | 46 347.14 (11 938.71) [19 146.00 to 123 966.00] |

| Households receiving public assistance, % | 2.54 (1.63) [0.00 to 24.83] |

| Population aged ≥16 who are unemployed, % | 4.65 (3.09) [0.00 to 100.00] |

| Households with female heads of house, % | 16.93 (6.52) [0.00 to 52.09] |

| Population aged ≥25 y without high school diploma, % | 15.06 (6.76) [1.27 to 53.28] |

| Crime per 100 population, 2010 data | |

| Property crimes | 2.24 (4.84) [0.00 to 109.04] |

| Violent crimes | 0.26 (0.76) [0.00 to 24.11] |

Calculated from total count of deaths from January 2010 to December 2014.

Table 3 shows results of the Bayesian, conditional, autoregressive, Poisson models for suicide deaths. Table 4 shows comparable results for homicide deaths. Both Table 3 and Table 4 also show analyses of suicide and homicide deaths, respectively, for various demographic characteristics of the counties. The reference group for the IRR was counties with high home state and high interstate policy scores.

Table 3. Multilevel Bayesian Conditional Autoregressive Poisson Models for Counts of Suicide by Firearms (January 2010-December 2014) for Counties (N = 3108) Nested Within Contiguous US States (N = 48).

| Description | IRR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1A: Firearm Suicide | Model 1B: Nonfirearm Suicide | Model 1C: All Suicide | |

| Firearm Policies | |||

| Low home state, low interstate | 1.35 (1.11-1.65)a | 1.02 (0.89-1.18) | 1.19 (1.05-1.35)a |

| Low home state, medium interstate | 1.36 (1.15-1.65)a | 1.04 (0.92-1.18) | 1.23 (1.10-1.39)a |

| Low home state, high interstate | 1.43 (1.20-1.73)a | 1.06 (0.95-1.20) | 1.23 (1.10-1.34)a |

| Medium home state, low interstate | 1.35 (1.07-1.71)a | 0.96 (0.82-1.13) | 1.16 (1.00-1.35)a |

| Medium home state, medium interstate | 1.24 (1.06-1.49)a | 1.05 (0.94-1.18) | 1.17 (1.01-1.27)a |

| Medium home state, high interstate | 1.22 (1.06-1.45)a | 1.06 (0.96-1.169) | 1.11 (1.01-1.23)a |

| High home state, low interstate | 0.91 (0.71-1.16) | 1.00 (0.87-1.16) | 0.93 (0.79-1.10) |

| High home state, medium interstate | 1.19 (0.98-1.45) | 0.99 (0.79-1.25) | 1.11 (0.95-1.29) |

| High home state, high interstate | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Census Characteristics | |||

| Population (model offset) | |||

| Area (1000 sq miles) | 1.02 (1.01-1.03)a | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) | 1.01 (1.01-1.02)a |

| Maleb | 1.01 (1.01-1.02)a | 1.02 (1.01-1.03)a | 1.02 (1.01-1.02)a |

| Median age (for each 10 y increase) | 1.31 (1.27-1.35)a | 1.16 (1.12-1.20)a | 1.24 (1.21-1.28)a |

| Blackb | 0.92 (0.90-0.94)a | 0.82 (0.80-0.83)a | 0.88 (0.86-0.89)a |

| Hispanicb | 0.89 (0.88-0.91)a | 0.94 (0.92-0.96)a | 0.91 (0.90-0.92)a |

| Median household income (for each additional $10 000) | 0.92 (0.90-0.93)a | 1.01 (1.00-1.03) | 0.96 (0.95-0.97)a |

| Households receiving public assistanceb | 0.99 (0.89-1.10) | 1.26 (1.13-1.40)a | 1.12 (1.04-1.21)a |

| Population aged ≥16 y who are unemployedb | 1.17 (1.08-1.26)a | 1.04 (0.94-1.14) | 1.11 (1.04-1.17)a |

| Households with female heads of houseb | 0.92 (0.88-0.96)a | 1.40 (1.33-1.47)a | 1.11 (1.07-1.15)a |

| Population aged ≥25 y without high school diplomab | 1.01 (0.98-1.05) | 0.81 (0.84-0.91)a | 0.97 (0.94-1.00)a |

| Crime | |||

| Property crimes (1 per 100 population) | 1.01 (1.00-1.01)a | 1.02(1.01-1.03)a | 1.01 (1.01-1.02)a |

| Violent crimes (1 per 100 population) | 1.03 (0.98-1.07) | 1.00 (0.96-1.05) | 1.02 (0.98-1.05) |

Abbreviations: CI, credible interval; IRR, incidence rate ratio.

Estimates have credible intervals that do not include an IRR of 1.0. Parameter estimates for county population constrained to an IRR of 1.0.

For each 10% of population.

Table 4. Multilevel Bayesian Conditional Autoregressive Poisson Models for Counts of Homicide by Firearms (January 2010-December 2014) for Counties (N = 3108) Nested Within Contiguous US States (N = 48).

| Description | IRR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 2A: Firearm Homicide | Model 2B: Nonfirearm Homicide | Model 2C: All Homicide | |

| Firearm Policies | |||

| Low home state, low interstate | 1.38 (1.02-1.88)a | 1.24 (0.99-1.57) | 1.32 (1.03-1.67)a |

| Low home state, medium interstate | 1.33 (1.02-1.75)a | 1.29 (1.04-1.60)a | 1.28 (1.03-1.59)a |

| Low home state, high interstate | 1.18 (0.89-1.54) | 0.97 (0.78-1.20) | 1.07 (0.86-1.32) |

| Medium home state, low interstate | 1.22 (0.88-1.70) | 1.17 (0.90-1.53) | 1.22 (1.00-1.49) |

| Medium home state, medium interstate | 1.22 (0.95-1.56) | 1.16 (0.95-1.41) | 1.13 (1.01-1.27) |

| Medium home state, high interstate | 1.15 (0.94-1.39) | 1.09 (0.91-1.29) | 1.13 (0.96-1.32) |

| High home state, low interstate | 1.13 (0.84-1.53) | 1.11 (0.84-1.45) | 1.11 (0.95-1.29) |

| High home state, medium interstate | 1.11 (0.74-1.65) | 0.95 (0.64-1.39) | 1.07 (0.78-1.48) |

| High home state, high interstate | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Census Characteristics | |||

| Population (model offset) | |||

| Area (1000 sq miles) | 1.03 (1.01-1.06)a | 1.35 (1.11-1.65)a | 1.04 (1.02-1.06)a |

| Maleb | 0.98 (0.96-1.00)a | 1.04 (1.02-1.05)a | 1.00 (0.99-1.01) |

| Median age (for each 10 y increase) | 1.13 (1.04-1.24)a | 1.07 (1.01-1.13)a | 1.09 (1.03-1.16)a |

| Blackb | 1.20 (1.15-1.25)a | 0.98 (0.95-1.02) | 1.12 (1.08-1.15)a |

| Hispanic (for each 10% of population) | 1.06 (1.01-1.11)a | 0.94 (0.91-0.97)a | 1.01 (0.98-1.04) |

| Median household income (for each additional $10 000) | 0.94 (0.90-0.98)a | 0.97 (0.94-1.00)a | 0.95 (0.92-0.98)a |

| Households receiving public assistanceb | 1.75 (1.42-2.14)a | 1.34 (1.15-1.66)a | 1.66 (1.42-1.95)a |

| Population aged ≥16 y who are unemployedb | 0.88 (0.72-1.08) | 0.952 (0.787-1.141) | 0.90 (0.77-1.06) |

| Households with female heads of houseb | 1.29 (1.16-1.41)a | 1.57 (1.44-1.71)a | 1.41 (1.29-1.52)a |

| Population aged ≥25 y without high school diplomab | 1.08 (1.00-1.18)a | 1.11 (1.04-1.19)a | 1.08 (1.02-1.15)a |

| Crime | |||

| Property crimes (1 per 100 population) | 1.04 (1.03-1.06)a | 1.03 (1.02-1.04)a | 1.04 (1.02-1.05)a |

| Violent crimes (1 per 100 population) | 1.15 (1.06-1.26)a | 1.14 (1.06-1.3)a | 1.15 (1.07-1.22)a |

Abbreviations: CI, credible interval; IRR, incidence rate ratio

Estimates have credible intervals that do not include an IRR of 1.0. Parameter estimates for county population constrained to an IRR of 1.0.

For each 10% of population.

As shown in Table 3, model 1A, counties with low-strength home state policy laws had the highest rates of firearm suicide. Rates were similar across levels of interstate policy score (low: IRR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.11-1.65; medium: IRR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.15-1.65; and high: IRR, 1.43; 95% CI 1.20-1.73). Counties with medium-strength home state policy scores had slightly lower rates of firearm suicide; counties with high-strength home state policy scores had the lowest rates. Firearm suicide rates for counties with medium-strength policy scores were also similar across levels of interstate policy score. Counties with high home state policy scores had equivalent rates of firearm suicide, regardless of interstate policy score level. These relationships carried over, though attenuated, to the total suicide rate, as shown in model 1C. There was no association between either state or interstate policy scores and nonfirearm suicide, as shown in model 1B. Factors associated with higher suicide rates in counties, firearm and otherwise, included a higher median age of residents and a higher proportion of male residents. Factors associated with lower suicide rates included higher percentages of black or Hispanic residents. Counties with higher percentages of households headed by women had lower firearm suicide rates but higher rates of nonfirearm suicide rates and overall suicide.

For homicides, as shown in Table 4, model 2A, counties with low home state and low or medium interstate policy scores had the highest rates of firearm homicide. Findings for nonhomicide and overall homicide rates are shown in model 2B and model 2C, respectively. Compared with counties with high home state and interstate policy scores, counties with low home state and interstate scores had higher firearm homicide rates (IRR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.02-1.88) and overall homicide rates (IRR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.03-1.67) but not nonfirearm homicides (IRR, 1.24; 95% CI, 0.99-1.57). Counties with low home state scores and medium interstate policy scores had higher rates of firearm homicide (IRR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.02-1.75), nonfirearm homicide (IRR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.04-1.60), and overall homicide (IRR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.03-1.59). In contract, counties with low state policy scores and high interstate policy scores did not have higher firearm homicide rates (IRR, 1.18; 95% CI, 0.89-1.54), nonfirearm homicide rates (IRR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.78-1.20), or overall homicide (IRR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.86-1.32). For counties with medium or high home state scores, homicide rates (firearm, nonfirearm, and overall) were not associated with the interstate policy score, regardless of whether it was low, medium, or high.

Factors associated with higher firearm homicide rates in counties included higher percentages of black or Hispanic residents, more households receiving public assistance, more households headed by women, and higher percentages of residents without a high school diploma. Higher rates of firearm homicides were associated with higher rates of property crimes and violent crimes and were inversely associated with higher median household income.

Results of the sensitivity analyses for suicide or homicide are available in eTable 2 and eTable3 in the Supplement, respectively. Results for suicide were not substantively different from those in the main analyses. For homicide, only the main analyses demonstrated an association between either home state or interstate firearm policies and homicides.

Discussion

In a national, cross-sectional analysis of state firearm policies, we found that counties in states with high firearm policy scores had the lowest rates of firearm suicide and overall suicide, regardless of the strength of the firearm policies of other states. We also found that counties in states with high firearm policy scores had lower rates of firearm homicide. Counties in states with low firearm policy scores had lower rates of firearm homicide only if the interstate firearm policy score was high.

Prior studies have provided indirect evidence for interstate spillover effects of state firearm laws and firearm death rates. In 2006, Webster et al49 found that the proportion of out-of-state firearms recovered in crimes in US cities was associated with proximity to states with permissive firearm policies. Law enforcement firearm trace data has consistently shown that states with stronger firearm control policies are the source of proportionately fewer firearms used in crimes.29 Likewise, a Virginia law limiting handgun purchases to 1 per month was associated with a decreased proportion of Virginia firearms recovered in crime nationwide.31 The Federal Assault Weapons Ban was passed in 1994, prohibiting the manufacture, possession and sale of certain military-style, semiautomatic firearms and large-capacity ammunition magazines in the United States. This ban expired automatically in 2004. Dube et al50 evaluated the effect of this expiration on firearm violence in Mexican towns, finding an increase in firearm-related homicides near the Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico border. California had a 1989 state assault weapons ban in place, so there was no effective policy change in California in 2004, and Dube et al50 found no increase in homicides near the California border.

Suicides account for two-thirds of all firearm-related deaths in the United States.3,51 We found that stronger home-state firearm policies were associated with lower firearm suicide rates, independent of the strength of the firearm policies of other states. We identified a partial substitution effect, as nonfirearm suicide rates were higher in counties with higher interstate policy scores, but overall suicide rates remained lower, consistent with prior studies.17,23,52,53,54,55,56,57,58 Because suicidal ideation is often transient, and because firearms are a highly lethal method of suicide, access to firearms is an important risk factor for completed suicide attempts.35,53 Considered in the context of prior studies, our findings provide evidence that stronger state firearm laws could help to prevent firearm suicides, without an equivalent increase in suicide by other methods.17,54,55

We found no relationship between firearm suicide rates in counties and the strength of the firearm laws of nearby states. This finding is consistent with prior studies showing that most firearm suicides are committed by firearm owners or their family members, and likely involve legally purchased firearms obtained for other purposes.35,53,54,59

We found the highest rates of firearm homicide and overall homicide in counties with low state and interstate policy scores. Counties with low state policy scores had lower firearm homicide rates when the interstate policy scores were high. In contrast, counties in states with high policy scores had lower rates of firearm homicide even when the interstate policy score was low. Prior studies have had mixed results with regard to the relationship between state firearm laws and firearm homicides.7,13,58,60,61,62,63 We did not identify a difference in homicide rates between counties in states with medium and high firearm policy scores. Fleegler et al,13 however, found an association between strong state firearm laws and lower rates of firearm-related fatalities. Firearm laws in the United States are generally lenient. Thus, in our geographic analysis there may have been insufficient variation between states to discern such an effect. Adjustment for county demographics may also have obscured a state-level association, as found in other studies. We did find higher rates of nonfirearm homicide in counties with low state policy scores and medium interstate policy scores, although not in those with low or high interstate policy scores. Possible explanations include an increase in general violent activity associated with increases in firearm homicide, or an unrecognized confounder that we were unable to identify. Our sensitivity analyses did not identify an association between firearm policies and firearm homicide rates. Analyses were consistent for suicide, likely because there is a continuous effect between home state policy strength and firearm suicide, with no effect from interstate policy strength. For homicide, we identified a nonlinear interaction between the home state and interstate policy scores. No other model that we tested allowed for either a nonlinear effect or a nonlinear interaction, which may explain why we did not detect a relationship between home or interstate policy score and homicide in these other models.

Limitations

Our analysis has limitations. First, because US state firearm laws are generally more lenient than in the other countries, and with only a few states with strict laws, our ability to detect an effect of the strictest laws may have been limited.10,26,55,64,65 Second, we used distance as a proxy for the ability of firearms to travel from one location to another. However, Federal Bureau of Investigation trace data indicated that firearms discovered in crime often originate in distant states, not adjoining states, an observation that held low weight in our analysis (based on inverse distance).29 Mail and internet commerce may mitigate the barrier of distance, as may cultural affinities between locations. Firearms may travel across state borders in specific ways, such as on interstate highways.29,66 Further research should consider such dynamics. Third, our cumulative policy score might mask the effect of a particular law, as seen in prior studies.12,15,28,62 The laws we analyzed cannot completely eliminate gun theft or illegal, deceptive purchases, and we could not account for differences in law enforcement between counties or states. Fourth, in a cross-sectional analysis, we were unable to test for a causal relationship between state policies and firearm deaths. Fifth, certain municipalities have stronger firearm restrictions than their states, and our analysis does not account for this. Sixth, confounding factors may vary between homicide and suicide, but we included broadly relevant variables, such as age and sex, to avoid overadjustment.67 Seventh, an unmeasured variable may contribute to both the adoption of state firearm laws and death rates. Finally, limitations to available data required us to use counties as spatial units of analysis. County boundaries are nonrandom, arbitrary, and include populations of up to 10 million. We used land area and population to calculate population density, but it is possible that certain counties have low population density but are very close to high-density centers and thus have distinctive properties. Future research on the impact of firearm policies should continue to assess both local and distant effects.

Conclusions

In this study of the geographic dynamics of firearm policy, stronger home state policies were associated with lower rates of firearm suicide and overall suicide regardless of the strength of other states’ laws. Stronger home state laws were associated with lower rates of firearm homicide, while counties in states with weaker laws had lower rates of firearm homicide only when surrounding states had stronger laws. Our findings support strengthening state firearm policies to reduce the incidence of both firearm suicide and homicide, with benefits that may extend across state lines.

eMethods

eTable 1. List of sensitivity analyses

eFigure. Rates of firearm homicide and firearm suicide in US counties, 2010-2014

eTable 2. Bayesian conditional autoregressive Poisson models for counts of homicide deaths, 3108 counties nested within 48 states

eTable 3. Bayesian conditional autoregressive Poisson models for counts of homicide deaths, 3108 counties nested within 48 states

References

- 1.Wintemute GJ. The epidemiology of firearm violence in the twenty-first century United States. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36(1):5-19. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031914-122535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinbrook R, Stern RJ, Redberg RF. Firearm injuries and gun violence: call for papers. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(5):596-597. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.0937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U. S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Vital Statisitcs Reports, Volume 65, Number 4.; 2016. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr65/nvsr65_04.pdf. Accessed November 21, 2016.

- 4.Wahowiak L. Public health taking stronger approach to gun violence: APHA, Brady team up on prevention. http://thenationshealth.aphapublications.org/content/45/10/1.3.full. Accessed November 21, 2016.

- 5.Obama B. Whitehouse.gov. Remarks by the president on common-sense gun safety reform. https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2016/01/05/remarks-president-common-sense-gun-safety-reform. Published January 5, 2016. Accessed May 15, 2016.

- 6.Stewart RM, Kuhls DA. Firearm injury prevention: a consensus approach to reducing preventable deaths. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;80(6):850-852. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee LK, Fleegler EW, Farrell C, et al. Firearm laws and firearm homicides: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(1):106-119. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steinbrook R, Stern RJ, Redberg RF. Firearm violence: a JAMA Internal Medicine series. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(1):19-20. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alcorn T. Trends in research publications about gun violence in the United States, 1960 to 2014. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(1):124-126. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hemenway D, Miller M. Public health approach to the prevention of gun violence. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(21):2033-2035. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1302631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence - Annual Gun Law State Scorecard 2015. http://gunlawscorecard.org/. Accessed May 15, 2016.

- 12.Kalesan B, Mobily ME, Keiser O, Fagan JA, Galea S. Firearm legislation and firearm mortality in the USA: a cross-sectional, state-level study. Lancet. 2016;387(10030):1847-1855. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01026-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fleegler EW, Lee LK, Monuteaux MC, Hemenway D, Mannix R. Firearm legislation and firearm-related fatalities in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(9):732-740. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sumner SA, Layde PM, Guse CE. Firearm death rates and association with level of firearm purchase background check. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(1):1-6. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Irvin N, Rhodes K, Cheney R, Wiebe D. Evaluating the effect of state regulation of federally licensed firearm dealers on firearm homicide. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(8):1384-1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vernick JS, Webster DW, Bulzacchelli MT, Mair JS. Regulation of firearm dealers in the United States: an analysis of state law and opportunities for improvement. J Law Med Ethics. 2006;34(4):765-775. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2006.00097.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crifasi CK, Meyers JS, Vernick JS, Webster DW. Effects of changes in permit-to-purchase handgun laws in Connecticut and Missouri on suicide rates. Prev Med. 2015;79:43-49. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Webster DW, Vernick JS, Hepburn LM. Effects of Maryland’s law banning “Saturday night special” handguns on homicides. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155(5):406-412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Webster D, Crifasi CK, Vernick JS. Effects of the repeal of Missouri’s handgun purchaser licensing law on homicides. J Urban Health. 2014;91(2):293-302. doi: 10.1007/s11524-014-9865-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sen B, Panjamapirom A. State background checks for gun purchase and firearm deaths: an exploratory study. Prev Med. 2012;55(4):346-350. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruddell R, Mays GL. State background checks and firearms homicides. J Crim Justice. 2005;33(2):127-136. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2004.12.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rudolph KE, Stuart EA, Vernick JS, Webster DW. Association between Connecticut’s permit-to-purchase handgun law and homicides. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(8):e49-e54. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loftin C, McDowall D, Wiersema B, Cottey TJ. Effects of restrictive licensing of handguns on homicide and suicide in the District of Columbia. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(23):1615-1620. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199112053252305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Webster DW, Vernick JS, eds. Reducing Gun Violence in America: Informing Policy with Evidence and Analysis. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wintemute GJ, Braga AA, Kennedy DM. Private-party gun sales, regulation, and public safety. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(6):508-511. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1006326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hahn RA, Bilukha O, Crosby A, et al. ; Task Force on Community Preventive Services . Firearms laws and the reduction of violence: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(2)(suppl 1):40-71. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Santaella-Tenorio J, Cerdá M, Villaveces A, Galea S. What do we know about the association between firearm legislation and firearm-related injuries? Epidemiol Rev. 2016;38(1):140-157. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxv012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Webster DW, Vernick JS, Hepburn LM. Relationship between licensing, registration, and other gun sales laws and the source state of crime guns. Inj Prev. 2001;7(3):184-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mayors AIG. Trace the Guns. https://tracetheguns.org/report.pdf. Published September 2010. Accessed January 17, 2018.

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention DC WONDER. https://wonder.cdc.gov/. Accessed May 12, 2016.

- 31.Weil DS, Knox RC. Effects of limiting handgun purchases on interstate transfer of firearms. JAMA. 1996;275(22):1759-1761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bureau of Alcohol Tobacco and Firearms Youth Crime Gun Interdiction Initiative, Crime Gun Trace Reports (2000). Washington, DC; U.S. Department of the Treasury; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wright MA, Wintemute GJ, Webster DW. Factors affecting a recently purchased handgun’s risk for use in crime under circumstances that suggest gun trafficking. J Urban Health. 2010;87(3):352-364. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9437-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siegel M, Rothman EF. Firearm ownership and suicide rates among US men and women, 1981-2013. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(7):1316-1322. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wiebe DJ. Homicide and suicide risks associated with firearms in the home: a national case-control study. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41(6):771-782. doi: 10.1067/mem.2003.187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vernick JS, Alcorn T, Horwitz J. Background checks for all gun buyers and gun violence restraining orders: state efforts to keep guns from high-risk persons. J Law Med Ethics. 2017;45(1_suppl):98-102. doi: 10.1177/1073110517703344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodrigue J-P, Comtois C, Slack B. The Geography of Transport Systems. 2nd ed London, New York: Routledge; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fotheringham AS. Spatial structure and distance-decay parameters. Ann Assoc Am Geogr. 1981;71(3):425-436. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fotheringham AS. A new set of spatial-interaction models: the theory of competing destinations. Environ Plann A. 1983;15(1):15-36. doi: 10.1068/a150015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.United States Census Bureau Census.gov. https://www.census.gov/. Accessed May 15, 2016.

- 41.Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277(5328):918-924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.United States Department of Justice. Federal Bureau of Investigation Uniform Crime Reporting Program Data: County-Level Detailed Arrest and Offense Data, 2012 (ICPSR 35019). 2014. http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/NACJD/studies/35019. Accessed November 29, 2016. 10.3886/ICPSR35019.v1. [DOI]

- 43.Waller LA, Gotway CA. Applied Spatial Statistics for Public Health Data. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Best N, Richardson S, Thomson A. A comparison of Bayesian spatial models for disease mapping. Stat Methods Med Res. 2005;14(1):35-59. doi: 10.1191/0962280205sm388oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Imprialou M-IM, Quddus M, Pitfield DE, Lord D. Re-visiting crash-speed relationships: a new perspective in crash modelling. Accid Anal Prev. 2016;86:173-185. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2015.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lunn DJ, Thomas A, Best N, Spiegelhalter D. WinBUGS—a Bayesian modelling framework: concepts, structure, and extensibility. Stat Comput. 2000;10(4):325-337. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lord D, Washington SP, Ivan JN. Poisson, Poisson-gamma and zero-inflated regression models of motor vehicle crashes: balancing statistical fit and theory. Accid Anal Prev. 2005;37(1):35-46. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2004.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dunteman GH. Principal Components Analysis. Nachdr. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publishing; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Webster DW, Vernick JS, Bulzacchelli MT. Effects of a gun dealer’s change in sales practices on the supply of guns to criminals. J Urban Health. 2006;83(5):778-787. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9073-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dube A, Dube O, García-Ponce O. Cross-border spillover: U.S. gun laws and violence in Mexico. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2013;107(03):397-417. doi: 10.1017/S0003055413000178 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fowler KA, Dahlberg LL, Haileyesus T, Annest JL. Firearm injuries in the United States. Prev Med. 2015;79:5-14. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ludwig J, Cook PJ. Homicide and suicide rates associated with implementation of the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act. JAMA. 2000;284(5):585-591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Swanson JW, Bonnie RJ, Appelbaum PS. Getting serious about reducing suicide: more “how” and less “why.” JAMA. 2015;314(21):2229-2230. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.15566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anestis MD, Khazem LR, Law KC, et al. The association between state laws regulating handgun ownership and statewide suicide rates. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(10):2059-2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chapman S, Alpers P, Agho K, Jones M. Australia’s 1996 gun law reforms: faster falls in firearm deaths, firearm suicides, and a decade without mass shootings. Inj Prev. 2015;21(5):355-362. doi: 10.1136/ip.2006.013714rep [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Miller M, Azrael D, Hepburn L, Hemenway D, Lippmann SJ. The association between changes in household firearm ownership and rates of suicide in the United States, 1981-2002. Inj Prev. 2006;12(3):178-182. doi: 10.1136/ip.2005.010850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McCourt AD, Vernick JS, Betz ME, Brandspigel S, Runyan CW. Temporary transfer of firearms from the home to prevent suicide: legal obstacles and recommendations. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(1):96-101. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rosengart M, Cummings P, Nathens A, Heagerty P, Maier R, Rivara F. An evaluation of state firearm regulations and homicide and suicide death rates. Inj Prev. 2005;11(2):77-83. doi: 10.1136/ip.2004.007062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Barber C, Frank E, Demicco R. Reducing Suicides through partnerships between health professionals and gun owner groups—beyond Docs vs Glocks. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(1):5-6. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.6712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Beaver BL, Woo S, Voigt RW, et al. Does handgun legislation change firearm fatalities? J Pediatr Surg. 1993;28(3):306-308. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(93)90222-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hepburn L, Miller M, Azrael D, Hemenway D. The effect of nondiscretionary concealed weapon carrying laws on homicide. J Trauma. 2004;56(3):676-681. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000068996.01096.39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Crandall M, Eastman A, Violano P, et al. Prevention of firearm-related injuries with restrictive licensing and concealed carry laws: an Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma systematic review. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;81(5):952-960. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kalesan B, Vasan S, Mobily ME, et al. State-specific, racial and ethnic heterogeneity in trends of firearm-related fatality rates in the USA from 2000 to 2010. BMJ Open. 2014;4(9):e005628-e005628. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Grinshteyn E, Hemenway D. Violent death rates: the US Compared with other high-income OECD countries, 2010. Am J Med. 2016;129(3):266-273. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sloan JH, Kellermann AL, Reay DT, et al. Handgun regulations, crime, assaults, and homicide: a tale of two cities. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(19):1256-1262. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198811103191905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Aisch G, Keller J. How Gun Traffickers Get Around State Gun Laws. New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/11/12/us/gun-traffickers-smuggling-state-gun-laws.html. Published November 13, 2015. Accessed August 5, 2017.

- 67.Schisterman EF, Cole SR, Platt RW. Overadjustment bias and unnecessary adjustment in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiology. 2009;20(4):488-495. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181a819a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

eTable 1. List of sensitivity analyses

eFigure. Rates of firearm homicide and firearm suicide in US counties, 2010-2014

eTable 2. Bayesian conditional autoregressive Poisson models for counts of homicide deaths, 3108 counties nested within 48 states

eTable 3. Bayesian conditional autoregressive Poisson models for counts of homicide deaths, 3108 counties nested within 48 states