Abstract

Background

Immediate breast reconstruction (IBR) is often deferred, when post-mastectomy radiotherapy (PMRT) is anticipated, due to high complication rates. Nonetheless, because of robust data supporting improved health related quality of life associated with reconstruction, physicians and patients may be more accepting of trade-offs. The current study explores national trends of IBR utilization rates and methods in the setting of PMRT, using the National Cancer Data Base (NCDB). The study hypothesis is that prosthetic techniques have become the most common method of IBR in the setting of PMRT.

Methods

NCDB was queried from 2004-2013 for women, who underwent mastectomy with or without IBR. Patients were grouped according to PMRT status. Multivariate logistic regression was used to calculate odds of IBR in the setting of PMRT. Trend analyses were done for rates and methods of IBR using Poisson regression to determine incidence rate ratios (IRR).

Results

In multivariate analysis, radiated patients were 30% less likely to receive IBR (p<0.05). The rate increase in IBR was greater in radiated compared to non-radiated patients (IRR: 1.12 vs. 1.09). Rates of reconstruction increased more so in radiated compared to non-radiated patients for both implants (IRR 1.15 vs. 1.11) and autologous techniques (IRR 1.08 vs. 1.06). Autologous reconstructions were more common in those receiving PMRT until 2005 (p<0.05), with no predominant technique thereafter.

Conclusion

Although IBR remains a relative contraindication, rates of IBR are increasing to a greater extent in patients receiving PMRT. Implants have surpassed autologous techniques as the most commonly used method of breast reconstruction in this setting.

INTRODUCTION

The rate of immediate breast reconstruction (IBR) has been increasing in the US over the last decade, due, in part, to the passage and implementation of the Women’s Health and Cancer Rights Act of 1998 [1–4]. Although IBR is associated with enhanced postoperative health-related quality of life (HR-QOL) compared to delayed or no reconstruction [5–8], post-mastectomy radiation therapy (PMRT) is often considered a relative contraindication to IBR due to higher complication rates [9, 10]. Moreover, as indications for PMRT have broadened, for example to include patients with 1 – 3 positive lymph nodes, plastic surgeons are now increasingly required to consider the timing and method of breast reconstruction in this setting[11–13].

No national level study has compared trends in IBR rates and methods between patients who either receive PMRT or not [14, 15]. Such knowledge is vital for understanding current surgical practice patterns with an eye towards optimizing outcomes and developing an ideal reconstructive algorithm in radiated patients. For example, while some surgeons withhold autologous transfer until after completion of PMRT others acceptably radiate flaps.

The primary aim of this study is to evaluate national trends in IBR using the National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) to determine the extent to which delivery of PMRT remains a relative contraindication. The secondary aim is to analyze the method of IBR performed in patients undergoing PMRT. The study hypothesis is that prosthetic techniques have become the most common method of IBR in the setting of PMRT.

METHODS

The NCDB is a joint project of the American Cancer Society and the Commission on Cancer of the American College of Surgeons [16]. The NCDB was established in 1989 as a nationwide, facility-based, comprehensive clinical surveillance resource oncology data set, which currently captures 70% of all newly diagnosed malignancies in the US annually. The American College of Surgeons has executed a Business Associate Agreement, which includes a data use agreement with each of its Commission on Cancer accredited hospitals. The latest versions of NCDB Breast Participant User Files (PUF) were obtained by applying for the summer 2015 application cycle. The study was exempted from institutional review board approval as no patient identifiers were collected. Inclusion criteria consisted of women diagnosed with breast cancer from 2004 through 2013. The NCDB specific surgical codes were used to identify patients who underwent mastectomy with and without immediate reconstruction. Method of breast reconstruction was recorded for each available year of diagnosis. Patients were stratified by PMRT recipient status. Patients, who received radiation treatment before or during the mastectomy, and those with unknown radiation treatment status were excluded.

For analysis of overall reconstruction trends and its association with PMRT, all breast reconstruction codes including implants, autologous, combined (unspecified combination of implants and autologous tissue, e.g. latissimus and implant) and NOS (not otherwise specified) were used. However, for analysis of specific trends based on method of reconstruction, combined technique and NOS were excluded, as the precise nature of these reconstructions was unavailable. Socio-demographic covariates relevant to breast reconstruction were evaluated. Age, ethnicity, education level, income, insurance status, facility type, year of diagnosis and Charlson comorbidity score [17] were recorded. Oncologic variables included tumor size, number of positive lymph nodes, stage of breast cancer (AJCC Stage 0 – IV), and status of radiation treatment.

For trends in rate of reconstruction, the total number of implants and autologous reconstructions were adjusted per 100 mastectomies for each year of diagnosis. Trends based on method of breast reconstruction were evaluated separately for implants and autologous reconstruction by adjusting the total number of reconstructions per 1000 mastectomies. Trend analyses were performed using Poisson regression with year of diagnosis as the independent variable and rate of breast reconstruction as the dependent variable. Calculated incidence rate ratios (IRRs) represent annual average changes in rates over time (per year). For instance, IRR of 1.12 can be interpreted as 12% increase in the incident rate per year. Univariate analysis was performed using chi-square test to evaluate the effect of each covariate on the practice of breast reconstruction. Factors that had a significant association on a univariate analysis were included in the final logistic regression model. A binary logistic regression model was created to analyze the odds of receiving breast reconstruction in the setting of PMRT after adjusting for all other covariates. Statistical analysis was performed using STATA 12.0 (College Station, TX: Stata Corp LP) with a p value less than 0.05 considered to be significant.

RESULTS

A total of 752,378 patients were included for the final analysis. The overall IBR rate for the entire cohort was 29.35% (Table 1). Over the study period, cumulatively, a significantly higher proportion of non-radiated patients underwent IBR, compared to those receiving PMRT (31% vs. 23%, p <.01; Table 1). Results of binary logistic regression analysis are presented in Table 2. After adjusting for all covariates, patients who received PMRT remained 30% less likely to receive IBR compared to non-radiated counterparts (p<0.05).

Table 1.

Univariate Analysis of Association between PMRT and Immediate Breast Reconstruction rates

| PMRT Status | Reconstruction N (%) |

No Reconstruction N (%) |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| PMRT | 39,537 (23) | 133,229 (77) | 172,766 |

| No Radiation | 181,685 (31) | 397,927 (69) | 579,612 |

| Total | 221,222 | 531,156 | 752,378 |

PMRT: Post-Mastectomy Radiotherapy, p < .01

Table 2.

Univariate Logistic Regression Analysis Depicting Odds Of Immediate Breast Reconstruction by Characteristics

| Characteristics | Odds Ratio | 95 % CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radiation treatment | <0.01 | ||

| No | 1.00 | Referent | |

| Yes | 0.70 | 0.69 – 0.72 | |

| Age | 0.93 | 0.92 – 0.94 | <0.01 |

| Ethnicity | <0.01 | ||

| White | 1.00 | Referent | |

| Black | 0.79 | 0.77 – 0.81 | |

| Other | 0.55 | 0.53 – 0.56 | |

| No high school degree | <0.01 | ||

| [>21%] | 1.00 | Referent | |

| [13% – 20.9%] | 1.05 | 1.03 – 1.08 | |

| [7% – 12.9%] | 1.05 | 1.02 – 1.07 | |

| [< 7% ] | 1.18 | 1.15 – 1.21 | |

| Median income | <0.01 | ||

| [< $ 38,000] | 1.00 | Referent | |

| [$ 38,000 – $ 47,999] | 1.15 | 1.12 – 1.18 | |

| [$ 48,000 – $ 62,999] | 1.38 | 1.35 – 1.41 | |

| [> $ 63,000 ] | 1.91 | 1.86 – 1.96 | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Score | <0.01 | ||

| 0 | 1.00 | Referent | |

| 1 | 0.86 | 0.84 – 0.88 | |

| 2 | 0.58 | 0.56 – 0.61 | |

| Clinical T : Tumor Size | <0.01 | ||

| 0 | 1.00 | Referent | |

| In situ | 1.02 | 0.94 – 1.11 | |

| 1 (< 2cm) | 0.99 | 0.91 – 1.07 | |

| 2 (2 – 5 cm) | 0.90 | 0.83 – 0.98 | |

| 3 (> 5 cm) | 0.73 | 0.67 – 0.79 | |

| 4 | 0.45 | 0.41 – 0.50 | |

| Number of positive lymph nodes | <0.01 | ||

| 0 | 1.00 | Referent | |

| 1 - 3 | 0.86 | 0.84 - .87 | |

| ≥4 | 0.71 | 0.70 – 0.73 | |

| Stage of breast cancer | <0.01 | ||

| 0 | 1.00 | Referent | |

| I | 1.00 | 0.94 – 1.08 | |

| II | 0.85 | 0.79 – 0.91 | |

| III | 0.65 | 0.61 – 0.71 | |

| IV | 0.42 | 0.38 – 0.45 | |

| Insurance status | <0.01 | ||

| Uninsured | 1.00 | Referent | |

| Medicaid | 1.41 | 1.34 – 1.49 | |

| Medicare | 1.86 | 1.76 – 1.95 | |

| Other Government | 2.67 | 2.48 – 2.88 | |

| Private | 3.23 | 3.09 – 3.40 | |

| Facility type | <0.01 | ||

| CCP | 1.00 | Referent | |

| Other types | 1.64 | 1.37 – 1.97 | |

| CCCP | 1.70 | 1.66 – 1.74 | |

| Academic/Research | 2.26 | 2.20 – 2.31 | |

| INCP | 2.56 | 2.49 – 2.64 | |

| Year of diagnosis | <0.01 | ||

| 2004 | 1.00 | Referent | |

| 2005 | 1.09 | 1.06 – 1.13 | |

| 2006 | 1.20 | 1.16 – 1.24 | |

| 2007 | 1.45 | 1.40 – 1.50 | |

| 2008 | 1.70 | 1.64 – 1.75 | |

| 2009 | 2.07 | 2.01 – 2.14 | |

| 2010 | 2.48 | 2.40 – 2.56 | |

| 2011 | 2.81 | 2.73 – 2.90 | |

| 2012 | 3.27 | 3.17 – 3.37 | |

| 2013 | 3.70 | 3.59 – 3.82 |

CCP: Community Cancer Program, CCCP: Comprehensive Community Cancer Program, INCP: Integrated Network Cancer Program, PMRT: Post-Mastectomy Radiotherapy

During the study period, the overall reconstruction rate increased significantly from 18% to 41% (IRR: 1.10, p<0.05; Table 3). When stratified into subgroups, the proportion of patients who underwent breast reconstructions in the setting of PMRT significantly increased from 13% in 2004 to 33% in 2013 (IRR: 1.12, p<0.05). The IBR rate in non-radiated patients increased as well, but to a lesser degree (IRR: 1.09, p<0.05).

Table 3.

Immediate Breast Reconstruction Rates and Incidence Rate Ratio by PMRT Status

| Diagnosis Year |

Mastectomy N |

Reconstruction N |

Percentage of breast reconstruction (Number per100 Mastectomies) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | PMRT | No PMRT | |||

| 2004 | 62,742 | 11,482 | 18 | 13 | 19 |

| 2005 | 63,982 | 12,477 | 20 | 14 | 21 |

| 2006 | 67,540 | 14,214 | 21 | 15 | 23 |

| 2007 | 73,993 | 17,717 | 24 | 17 | 26 |

| 2008 | 79,116 | 21,062 | 27 | 20 | 29 |

| 2009 | 83,769 | 25,146 | 30 | 23 | 32 |

| 2010 | 82,508 | 26,845 | 33 | 26 | 35 |

| 2011 | 84,869 | 29,659 | 35 | 28 | 37 |

| 2012 | 87,350 | 32,853 | 38 | 31 | 40 |

| 2013 | 87,163 | 35,486 | 41 | 33 | 43 |

|

| |||||

| IRR* | 1.10 | 1.12 | 1.09 | ||

All IRR are significant with p < 0.05, IRR: Incident Rate Ratio, PMRT: Post-Mastectomy Radiotherapy

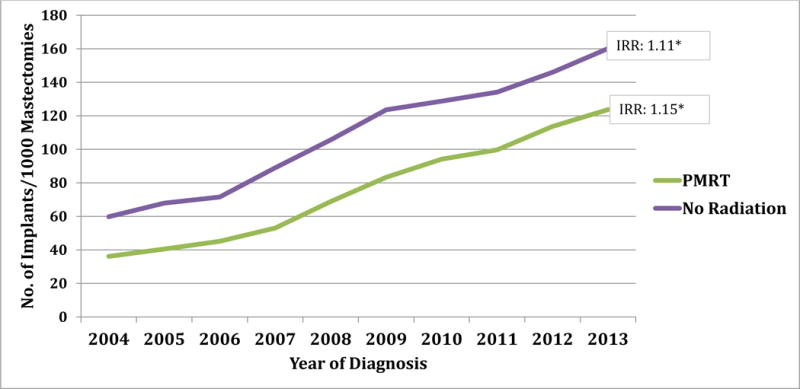

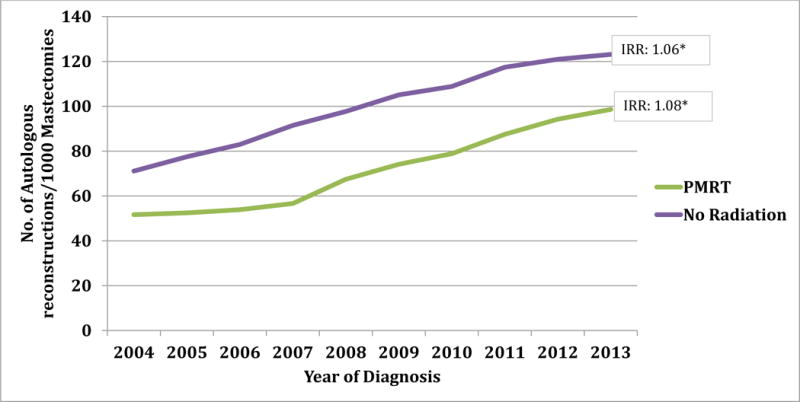

Examination of the reconstruction method showed that overall autologous rates increased during the study period, but to a greater extent in the radiated than non-radiated subgroups (IRR: 1.08 vs. 1.06; Figure 1). Similar trends were observed for prosthetic reconstructions, but to a greater degree. That is, prosthetic reconstruction use increased more rapidly in both radiated and non-radiated subgroups (Figure 2, IRR: 1.15 vs. 1.11).

Figure 1. Rate of implant based breast reconstructions from 2004 – 2013a.

a Does not include combined and ‘not otherwise specified’ codes of breast reconstruction.

* p value is significant (<0.05); Rate: Number of reconstruction per 1000 mastectomies IRR: Incident Rate Ratio, PMRT: Post-Mastectomy Radiation Therapy

Figure 2. Rate of Autologous Breast Reconstructions from 2004 – 2013b.

b Does not include combined and ‘not otherwise specified’ codes of breast reconstruction.

* p value is significant (<0.05); Rate: Number of reconstruction per 1000 mastectomies, IRR: Incident Rate Ratio, PMRT: Post-Mastectomy Radiation Therapy

The relative use of implants increased steadily over the study period with implants surpassing autologous tissue as the most common method in 2008 (Table 4). In 2004 and 2005 there was an association between autologous methods of reconstruction and PMRT (p<0.01). Thereafter, there was no significant relationship between PMRT delivery and IBR method.

Table 4.

Ratio of Implant to Autologous Reconstruction Technique by Post-Mastectomy Radiotherapy Statusa

| Diagnosis Year |

Implants to Autologous Breast Reconstruction Ratiob | |

|---|---|---|

| PMRT | No PMRT | |

| 2004 | 0.70 | 0.84* |

| 2005 | 0.77 | 0.88* |

| 2006 | 0.84 | 0.86 |

| 2007 | 0.94 | 0.97 |

| 2008 | 1.02 | 1.08 |

| 2009 | 1.12 | 1.18 |

| 2010 | 1.19 | 1.18 |

| 2011 | 1.14 | 1.14 |

| 2012 | 1.21 | 1.21 |

| 2013 | 1.25 | 1.30 |

Does not include combined and ‘not otherwise specified’ codes of breast reconstruction

A ratio of > 1.0 implies higher implants utilization than autologous tissue and vice versa.

P value calculated using Chi-Square for association between receipt of radiotherapy (PMRT Yes and No) and type of breast reconstruction (implant or autologous) for each year.

DISCUSSION

The high proportion of complications for IBR in the setting of radiation is established in the literature, leading to a variety of approaches to mitigate its side effects (9,10). The concern about complications is reflected by the lower overall rate of IBR in radiated compared to non-radiated groups (23% vs. 31% respectively). However, over a 10-year period using the NCDB, the proportion of IBRs in the setting of PMRT increased from 13% to 33%, suggesting it is a diminishing relative contraindication. Based on the consistency of these trends, it appears patients and plastic surgeons are increasingly willing to tradeoff the higher complication rates associated with PMRT for the HR-QOL benefits of IBR. Greater HR-QOL has been specifically reported by women who undergo immediate as opposed to delayed reconstruction [5–8]. The decision to proceed with IBR must also be weighed in light of the competing alternatives which include delayed autologous transfer (e.g. DIEP or latissimus with implant) or no reconstruction altogether.

The rate of implants and autologous breast reconstructions performed each year was evaluated to determine the relative use of these techniques both in the presence and absence of PMRT (Table 4). In 2004, autologous tissue was the predominant method of breast reconstruction in both radiated and non-radiated patients; however, since 2008 implants became preferred in both subgroups. Specifically for patients receiving PMRT, the rate of implant breast reconstruction increased over threefold (36 to 124 per 1000 mastectomies, IRR 1.15). These findings support the study hypothesis that over time implants have become the predominant method of IBR in radiated patients.

It is unclear if the expansion in the practice of implants use among patients undergoing PMRT is driven by the same reasons as the overall growth in use of prosthetic techniques nationwide [1]. There are some unique aspects of implant based reconstruction techniques in the setting of radiation. First, although HR-QOL with immediate prosthetic reconstruction is not optimized, prosthetic reconstruction in a delayed fashion is not possible after the chest wall skin has lost compliance from radiation fibrosis [9, 10]. Additionally, new approaches, for instance, radiating the tissue expander as opposed to the permanent implant, have been reported to have improved outcomes of prosthetics [18]. Thus, not offering IBR, potentially eliminates prosthetic techniques as an option for many patients. Second, implant removal in cases of radiation related complications such as capsular contracture or infection remains relatively straightforward. Lastly, placement of a tissue expander in a potential radiation candidate does not preclude the possibility for delayed autologous reconstruction. In this setting, the tissue expander serves as a temporary space holder and preserves the mastectomy pocket. There may be a cosmetic benefit with use of a smaller flap skin island on the chest wall for patients who undergo reconstruction in this sequence.

Perhaps, an area that deserves more attention by investigators is the use of autologous techniques in the setting of PMRT, especially given the greater long term HR-QOL associated with flaps [19, 20]. While some centers routinely radiate flaps, others believe this practice ruins a potential reconstructive lifeboat. Unfortunately, the literature varies widely with respect to outcomes on this topic. While some studies demonstrate no changes to the flap, others contend there is significant flap deflation and rates of fat necrosis [21]. A thoughtful prospective analysis on this topic might move the field forward towards a better understanding of the side effects of PMRT on immediate flap reconstruction.

The trends demonstrated herein reflect physicians’ estimates of the need for adjuvant treatments based on knowledge of preoperative clinical staging. This important piece of information influences the timing and method of breast reconstruction offered to patients as well as potential for complications. Although the indication for radiation delivery is not determined until postoperative pathological staging returns, the consistency of the findings and trends described supports plastic surgeons’ ability to preoperatively anticipate the need for PMRT. To overcome potential discordance between clinical and pathologic staging, a variety of algorithms have been developed with an eye towards minimizing complication rates associated with PMRT. One approach involves use of pre-mastectomy sentinel lymph node biopsy (PM-SLNB) [22]. In the presence of a positive sentinel lymph node, IBR is not offered, with delayed tissue transfer performed upon completion of PMRT. A second alternative is to place tissue expanders in all patients, also referred to as the delayed immediate approach. After interpretation of final pathology, patients determined not to need PMRT undergo autologous transfer within two weeks time. While both of these algorithms require additional steps, with incremental increases in time and cost to the reconstructive process, they may provide better value over the long run. As new health care models such as bundled payments and pay for performance are adopted, these approaches may become more appealing as they obviate the high complication rates associated with prosthetics and PMRT.

The current investigation is a comprehensive analysis of national breast reconstruction trends in the setting of PMRT. While a previous study using the SEER database from 2000-2010 demonstrated a similar expansion in implants [22], it did not include a non-radiated subgroup. To understand the impact of PMRT on breast reconstruction, it is imperative to compare breast reconstruction trends in radiated with a non-radiated cohort (control group). Importantly, the present study includes data through 2013, thus capturing the impact of broadened indications for PMRT recommendations by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network in 2009 [11]. Lastly, SEER has a smaller sample size than the NCDB, and has been shown to underreport PMRT utilization [23, 24] as well.

Limitations of this study include the following. No information is available in NCDB on delayed reconstruction so we could not evaluate those trends. There is also no data about clinical factors such as BMI, history of smoking, and previous abdominal surgery, all of which may play a significant role in selection of the type breast reconstruction technique. Because surgical outcomes are not recorded in the NCDB, their association with reconstructive method could not be determined. The role of patients’ preferences for one type of breast reconstruction over the other is not available for consideration.

CONCLUSION

IBR in the setting of PMRT is increasingly common in the US. Although autologous techniques were previously preferred, a large-scale shift to prosthetic techniques has been demonstrated in radiated as well as non-radiated subgroups.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748

Footnotes

Disclosure:

None of the authors report a financial interest in any of the products, devices, or drugs mentioned in this manuscript.

Conference Presentation:

Abstract of this study has been accepted for oral presentation at 33rd Annual Meeting of Northeastern Society of Plastic Surgeons Scheduled on Oct 14, 2016.

References

- 1.Albornoz CR, et al. A paradigm shift in U.S. Breast reconstruction: increasing implant rates. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131(1):15–23. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182729cde. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albornoz CR, et al. Diminishing relative contraindications for immediate breast reconstruction: a multicenter study. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;219(4):788–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farhangkhoee H, Matros E, Disa J. Trends and concepts in post-mastectomy breast reconstruction. J Surg Oncol. 2016;113(8):891–4. doi: 10.1002/jso.24201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garfein ES. The privilege of advocacy: legislating awareness of breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128(3):803–4. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182221501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Ghazal SK, et al. The psychological impact of immediate rather than delayed breast reconstruction. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2000;26(1):17–9. doi: 10.1053/ejso.1999.0733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chao LF, et al. Monitoring patient-centered outcomes through the progression of breast reconstruction: a multicentered prospective longitudinal evaluation. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;146(2):299–308. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-3022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elder EE, et al. Quality of life and patient satisfaction in breast cancer patients after immediate breast reconstruction: a prospective study. Breast. 2005;14(3):201–8. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teo I, et al. Body image and quality of life of breast cancer patients: influence of timing and stage of breast reconstruction. Psychooncology. 2015 doi: 10.1002/pon.3952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clemens MW, Kronowitz SJ. Current perspectives on radiation therapy in autologous and prosthetic breast reconstruction. Gland Surg. 2015;4(3):222–31. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2227-684X.2015.04.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kronowitz SJ, Robb GL. Radiation therapy and breast reconstruction: a critical review of the literature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(2):395–408. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181aee987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carlson RW, et al. Breast cancer. Clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7(2):122–92. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frasier LL, et al. Temporal Trends in Postmastectomy Radiation Therapy and Breast Reconstruction Associated With Changes in National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(1):95–101. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.3717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yao K, et al. Increased utilization of postmastectomy radiotherapy in the United States from 2003 to 2011 in patients with one to three tumor positive nodes. J Surg Oncol. 2015;112(8):809–14. doi: 10.1002/jso.24071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butler PD, et al. Racial and age disparities persist in immediate breast reconstruction: an updated analysis of 48, 564 patients from the 2005 to 2011 American College of Surgeons National Surgery Quality Improvement Program data sets. Am J Surg. 2016;212(1):96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kwok AC, et al. National trends and complication rates after bilateral mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction from 2005 to 2012. Am J Surg. 2015;210(3):512–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bilimoria KY, et al. The National Cancer Data Base: a powerful initiative to improve cancer care in the United States. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(3):683–90. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9747-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613–9. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kronowitz SJ. Delayed-immediate breast reconstruction: technical and timing considerations. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125(2):463–74. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181c82d58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jagsi R, et al. Patient-reported Quality of Life and Satisfaction With Cosmetic Outcomes After Breast Conservation and Mastectomy With and Without Reconstruction: Results of a Survey of Breast Cancer Survivors. Ann Surg. 2015;261(6):1198–206. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alderman AK, et al. Does patient satisfaction with breast reconstruction change over time? Two-year results of the Michigan Breast Reconstruction Outcomes Study. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204(1):7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelley BP, et al. A systematic review of morbidity associated with autologous breast reconstruction before and after exposure to radiotherapy: are current practices ideal? Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(5):1732–8. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3494-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agarwal S, et al. Immediate Reconstruction of the Radiated Breast: Recent Trends Contrary to Traditional Standards. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(8):2551–9. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-4326-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jagsi R, et al. Underascertainment of radiotherapy receipt in Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry data. Cancer. 2012;118(2):333–41. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walker GV, et al. Muddy water? Variation in reporting receipt of breast cancer radiation therapy by population-based tumor registries. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;86(4):686–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]