Abstract

Acute kidney injury (AKI) and chronic kidney disease (CKD) are worldwide public health problems affecting millions of people and have rapidly increased in prevalence in recent years. Due to the multiple causes of renal failure, many animal models have been developed to advance our understanding of human nephropathy. Among these experimental models, rodents have been extensively used to enable mechanistic understanding of kidney disease induction and progression, as well as to identify potential targets for therapy. In this review, we discuss AKI models induced by surgical operation and drugs or toxins, as well as a variety of CKD models (mainly genetically modified mouse models). Results from recent and ongoing clinical trials and conceptual advances derived from animal models are also explored.

Keywords: Acute kidney injury, Chronic kidney disease, Mouse models, Transgenic mice

INTRODUCTION

Foundation items: This study was supported by the General Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51309220, 31470776) and QianJiang Talent Plan to W.Q. Lin

Acute kidney injury (AKI) and chronic kidney disease (CKD) are linked to high morbidity and mortality. AKI is regarded as a rapid and reversible decline in renal function and is associated with accelerated CKD (Siew & Davenport, 2015). The ability to diagnose AKI has progressed significantly. Recent consensus diagnostic criteria include an increase in serum creatinine ≥0.3 mg/dL (≥26.5 µmol/L) within 48 h; an increase in serum creatinine to ≥1.5 times baseline; or urine volume <0.5 mL/kg/h for 6 h (Khwaja, 2012). Many risk factors such as drugs/toxins, sepsis, and ischemia-reperfusion (IR) commonly result in AKI and lead to reduced glomerular filtration rate (GFR) as well as acute tubular cell death (Sanz et al., 2013). CKD is a significant medical problem globally, with a rapid increase in incidence due to the rise in hypertension and diabetes (Tomino, 2014). CKD is usually diagnosed by the presence of albuminuria or estimated GFR from serum creatinine <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (Andrassy, 2013).

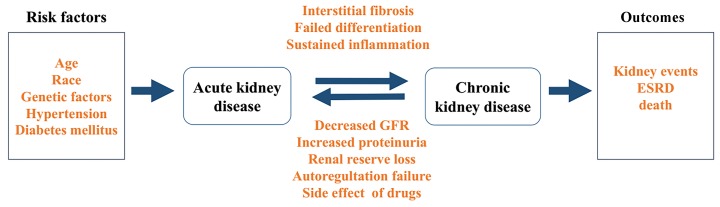

There is increasing recognition that AKI and CKD are closely linked and are therefore regarded as an integrated clinical syndrome (Chawla & Kimmel, 2012) (Figure 1). Key biological processes such as cell death, cell proliferation, inflammation, and fibrosis, as well as common biomarkers, are detected in both kinds of nephropathy (Andreucci et al., 2017; Endre et al., 2011). Generally, tubular cell death, which includes necrosis, apoptosis, or necroptosis, is the main histological feature in early stage AKI, whereas fibrosis tends to occur under CKD. An increasing number of studies have shown that AKI is a major risk factor that can accelerate CKD progression (Pannu, 2013). Clinical observations have also found a strong relationship between AKI and CKD. Compared to patients with no history of AKI or CKD, AKI patients are more likely to develop new CKD or end-stage renal disease (ESRD) (Chawla et al., 2014; Chawla & Kimmel, 2012). Conversely, CKD also plays an important role in AKI. Patients with CKD may suffer higher risk of transient decreases in renal function consistent with AKI (Chawla et al., 2014). The underlying mechanism that results in acute renal dysfunction may involve decreased GFR, increased proteinuria, renal auto-regulation failure, and drug side effects (Hsu & Hsu, 2016).

Figure 1.

Relationship between acute kidney injury (AKI) and chronic kidney disease (CKD)

AKI and CKD show some common risk factors such as age, race, and hypertension. Persistent AKI can induce interstitial fibrosis, failed cell differentiation, and finally CKD. Conversely, CKD also plays an important role in the development of AKI. Both are associated with an increased risk of death and can result in serious kidney events such as end-stage renal disease.

Mechanisms of disease generation and progression in AKI and CKD remain incompletely understood (Singh et al., 2013; Tampe et al., 2017). Although several clinical studies have investigated early stage predictive biomarkers of kidney disease, few has been applied in clinical practice (Endre et al., 2013; Francoz et al., 2016; Peng et al., 2008; Soto et al., 2010). Our group identified urinary fractalkine as a marker of acute kidney transplant rejection (Peng et al., 2008). However, considerable challenges still lay ahead for the design and implementation of clinical kidney disease trials. Large sample size and long follow-up duration are essential in a multicenter clinical trial to guarantee the quality, efficiency, and safety of intervention and treatments as there are many different types and causes of kidney disease and treatment can be protracted (Luyckx et al., 2013). Moreover, serious complications greatly contribute to total mortality in kidney disease (Di Lullo et al., 2015; Pálsson & Patel, 2014; Ross & Banerjee, 2013), making it difficult to determine the major cause and best treatment. Thus, mature animal models are an indispensable part of scientifically designed kidney disease studies, and play an important role in resolving the bottleneck issue in treatment.

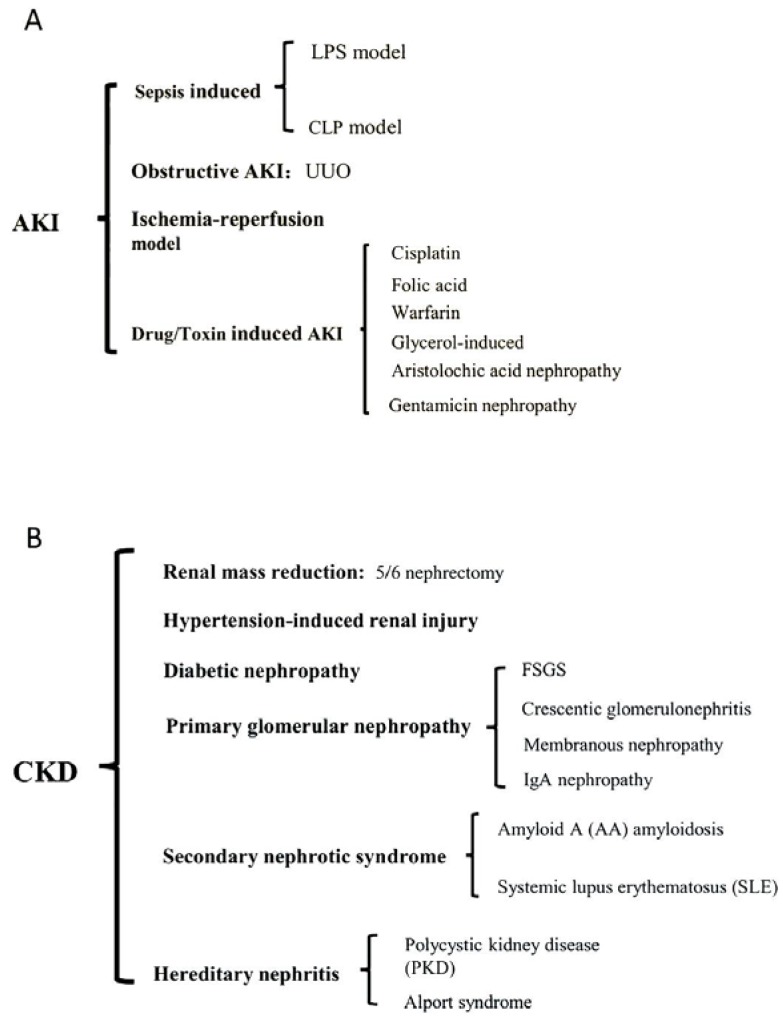

Animal models have been extensively used to clarify the pathogenesis and underlying mechanisms of renal disease. Among these models, mice and rats are the most commonly used to study nephropathy events and potential therapeutic targets and to identify specific biomarkers of disease. Mice and rats are easily bred and are relatively inexpensive to house and maintain (Wei & Dong, 2012). Classic acute kidney disease can be induced in a variety of murine models by surgery or administration of drugs or toxins (Ortiz et al., 2015; Singh et al., 2012). Furthermore, genetically engineered mice and inbred strains provide a new platform for investigating complex human nephropathy (such as IgA nephropathy and diabetic nephropathy) (Marchant et al., 2015; Suzuki et al., 2014). In this review, we focused on murine models of AKI and CKD (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Summary of major acute kidney injury (AKI) and chronic kidney disease (CKD) models

A: Common causes of acute kidney injury (AKI). Traditional animal modeling approaches are included. B: Classification of chronic kidney disease (CKD). The following are available animal models for CKD; UUO: Unilateral ureteral obstruction; FSGS: Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis.

ACUTE KIDNEY INJURY MODELS

Recently, several reviews of available models, including their advantages and disadvantages, have been discussed (Ortiz et al., 2015; Ramesh & Ranganathan, 2014); however, the types of models are incomplete and many details, such as model techniques and modeling time, are not mentioned. Current models of AKI can be induced by IR (pre-renal acute kidney failure), injection of drugs, toxins, or endogenous toxins (sepsis-associated AKI), and ureteral obstruction (post-renal acute kidney failure) (Sanz et al., 2013; Singh et al., 2012) (Table 1). This section will discuss experimental AKI models, surgical operations, model time courses, and drug/toxin dose ranges.

Table 1.

Comparison of conventional acute kidney injury (AKI) mice models

| Models | Species | Time-course/Dose range | Advantages | Disadvantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sepsis induced | Rats/mice | Cecal ligation and punctured to induce AKI; single i.p. dose of 10–15 mg/kg LPS are commonly used to induced AKI | Simple; inexpensive; standardized dose of LPS | Variable response between models; expected acute renal necrosis is not always achieved; AKI is not produced clinically and pathologically | Dejager et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2016 |

| Ischemia-reperfusion | Rats/mice | Ischemia time: 30–45 min; reperfusion time: 24–48 h | High clinical relevance; classical model with high knowledge background | Surgery requires; reproducible outcome dependent on accurate Ischemia/ Reperfusion time | Hesketh et al., 2014; Wei & Dong, 2012 |

| UUO | Rats/mice | 1–2 weeks; longer time for renal fibrosis studies | Technically simple; reproducible | Surgery requires; not widely used as AKI mode; renal function can be compensated by the non-ligated kidney; | Bander et al., 1985; Chevalier et al., 2009; Ucero et al., 2014 |

| Cisplatin | Rats/mice | Single does 6–20 mg/kg; cisplatin within 72 h to induce AKI | Simple and reproducible; similar to human renal disease | Requires higher does to induce AKI; the cisplatin use is decreased in clinical | Ko et al., 2014; Li et al., 2005; Morsy & Heeba, 2016; Xu et al., 2015 |

| Aristolochic acid | Rats/mice | 5 mg/kg/day Aristolochic acid for 5 days | Useful to study AKI-CKD transition; | No clinical correlate; less nephrotoxicity report | Matsui et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2014 |

| Folic acid | Rats/mice | Single dose of 250 mg/kg induce AKI in 24-48 h | Simple and reproducible | Wen et al., 2012; Soofi et al., 2013 | |

| Warfarin | Rats | 5/6 nephrectomy for 3 weeks and 8 days on warfarin | Clinically relevant; useful to study AKI caused by anticoagulants | Only modeled in rats | Brodsky, 2014; Ozcan et al., 2012; Ware et al., 2011 |

| Glycerol | Rats/mice | Deprived of water for 24 h and single injection of 8–10 mg/kg 50% glycerol | Simple; reproducible | Severe pathology | Geng et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2014 |

| Gentamicin | Rats | Dose range 40–200 mg/kg for 4–10 days | Highly relevant; reversible AKI | Requires higher dose of Gentamicin; different symptoms in human and rodents | Boroushaki et al., 2014; He et al., 2015; Heidarian et al., 2017 |

Sepsis-associated AKI

Sepsis-associated AKI (SA-AKI) is characterized by severe inflammatory complications and high morbidity and mortality (Swaminathan et al., 2015). Frequently used experimental models of SA-AKI can be divided into two types: (1) injection of bacteria or endogenous toxins (e.g., LPS) into the peritoneum or blood; and (2) release of intestinal excreta by cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) or colon ascendens stent peritonitis (CASP) (Xu et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2015a).

LPS models LPS-induced AKI has mainly been studied in rats and mice. Compared with other species, rodents are significantly more resistant to the toxic or lethal effects of LPS. The dose of LPS commonly used in research is 10–15 mg/kg (Fink, 2014; Liu et al., 2015b; Venkatachalam & Weinberg, 2012). After LPS interacts with specific receptors such as Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4) (Solov'eva et al., 2013) on host immune cells, inflammatory cytokines like IL-1, TNF-α, and IL-6 are secreted, leading to hemodynamic alteration, widespread inflammation, and sepsis (Solov'eva et al., 2013). This is an acute model that usually terminates at 72–96 h.

CLP model The CLP model is the most frequently used model due to its simplicity. Firstly, ligation of the cecum from the distal to the ileocecal valve is made. After that, two needle punctures are made to extrude stool into the abdominal cavity (Liu et al., 2016b; Poli-De-Figueiredo et al., 2008). CLP in mice can develop the typical symptoms of bacterial peritonitis observed in humans and yield good results (Fink, 2014). However, it is difficult to control the severity of sepsis and the differences in age and strain in CLP models (Zarjou & Agarwal, 2011). Moreover, reproducible AKI cannot be developed in a CLP model (Dejager et al., 2011).

Although experimental models have extended our understanding of sepsis and sepsis-associated AKI, there is still no effective clinical therapy (Alobaidi et al., 2015). Several clinical trials targeting specific signaling pathways based on convincing results in murine models have failed to improve survival in septic patients.

Ischemia-reperfusion (IR) model

Currently, IR is the most widely used model for clinical AKI and renal transplant studies (Hesketh et al., 2014). Among the variety of existing models, the mouse clamping model is often applied due to its low costs and choice of transgenic models (Sanz et al., 2013). According to previous studies, commonly used models contain bilateral renal IR (Huang et al., 2012; Hu et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2012) and unilateral renal IR (Braun et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2011; Gall et al., 2011).

First, 50–60 mg/kg of pentobarbital (5 mg/mL) is used to anesthetize mice by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection, with body temperatures then maintained at 36.5–37 °C during surgery. Second, the renal artery and vein are clamped by micro-aneurysm clips for a variable length of time to induce different severities of kidney injury. In general, clamping the renal pedicle for 30 min is used to induce IR injury (Huang et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2016a). Successful ischemia can be confirmed by gradual darkening of the kidney (from red to dark purple). The clamp is then removed at the desired time to achieve reperfusion, with the kidney color immediately reverting to red (Hesketh et al., 2014; Wei & Dong, 2012). Ischemia-reperfusion will trigger tubular cell necrosis and apoptosis, inflammation, and oxidative stress (Rovcanin et al., 2016; Sanz et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 2015), which can result in a decline of renal function, as evaluated by blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine. Despite the view that the IR model is less stable, experimental factors such as anesthesia dose, mouse strain, age, gender, and feeding conditions can be well-controlled (Wei & Dong, 2012).

Obstructive AKI

Unilateral ureteric obstruction (UUO) is the most common rodent model used to study AKI and CKD (Ucero et al., 2014). This model can result in hydronephrosis and blood flow changes. Ischemia, hypoxia, and oxidative stress (Dendooven et al., 2011) contribute to the tubular cell death, followed by interstitial inflammation. Additionally, transformed fibroblasts can interact with extracellular matrix deposition to cause renal fibrosis (Xiao et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2014).

Recent studies using the UUO model have shown that adenosine levels (Tang et al., 2015), nuclear factor-erythroid-2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) (Chung et al., 2014), interleukin-10 (Jin et al., 2013), and the JAK/STAT signaling pathway (Koike et al., 2014) are related to renal fibrosis, thus offering a potential therapeutic target for renal injury. The UUO model is relatively straightforward. Male animals, which are recommended in this model, undergo a midline abdominal incision under anesthesia, with the left ureter then ligated with 4–0 silk. After 24 h, the ureter obstruction is removed (Bander et al., 1985). Different from the complete UUO model, a partial UUO is created by inserting the ureter into a surgically created tunnel in the psoas muscle (Sugandhi et al., 2014). Reversible partial UUO is generally performed in neonatal mice to investigate kidney recovery after obstruction (Ucero et al., 2014). However, the complete UUO model is more popular because it is less technical and more easily reproduced.

Toxin-induced AKI

Exogenous drugs or poisons and endogenous toxins are used to stimulate AKI by their side or poisoning effects. Among these models, 6–20 mg/kg cisplatin can result in acute tubular injury within 72 h, whereas administration of 40–200 mg/kg gentamicin in rats for 4–10 d can induce acute renal failure. Aristolochic acid and high dose folic acid (FA) are frequently used to study AKI-CKD transition, with AKI models developed by warfarin and glycerol also used.

Cisplatin-induced AKI

Cisplatin is a chemotherapy agent that is widely used in the treatment of solid tumors (Karasawa & Steyger, 2015). However, high doses of cisplatin can induce prominent nephrotoxicity in humans (Humanes et al., 2012; Malik et al., 2015). Among cisplatin’s adverse effects, direct proximal tubular toxicity is significant. Tubular cell necrosis and apoptosis are mediated by inflammation, oxidative stress, and calcium overload. These modes of cell death both lead to increased vascular resistance and decreased GFR (Ozkok & Edelstein, 2014). The pathology and recovery phase of cisplatin-induced AKI models are comparable with those of humans. Many studies have reported that single i.p. injection of 6–20 mg/kg cisplatin can induce AKI within 72 h in rodent models (Ko et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2009; Morsy & Heeba, 2016; Xu et al., 2015). Furthermore, other groups have developed AKI models by injecting higher doses of cisplatin, including 30 mg/kg, i.p. (Lu et al., 2008; Mitazaki et al., 2009) and 40 mg/kg, i.p. (Zhang et al., 2016). Based on results from this experimental model, several therapeutic targets have been established.

Aristolochic acid nephropathy

It has been reported that i.p. injection of aristolochic acid (AA) (5 mg/kg/d for 5 d) can induce AKI (Matsui et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2014). The pathology of acute aristolochic acid nephropathy (AAN) involves proximal tubular cell injury and necrosis with oxidative stress and progressive interstitial renal fibrosis (Baudoux et al., 2012; Nortier et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2010). Rabbit and rat models were first used to recapitulate human CKD and confirmed that aristolochic acid is related to Chinese herb nephropathy and Balkan endemic nephropathy (De Broe, 2012; Sanz et al., 2013). Recently, studies on AA in AKI-CKD transition have increased. Signaling pathways such as nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) (Wu et al., 2014) and Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK) signaling (Rui et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2010) have been shown to play important roles in AA-induced acute kidney lesions, thus providing several new therapeutic targets.

Folic acid-induced AKI

A high dose of FA can also induce AKI in mice (Wen et al., 2012). Intraperitoneal injection of 250 mg/kg of FA (dissolved in 0.3 mmol/L NaHCO3) can cause acute renal toxicity and injury in rodents (Soofi et al., 2013; Wen et al., 2012). The mechanism of FA nephropathy might be due to FA crystal deposition in the tubular lumen, which results in obstruction and extensive necrosis (Kumar et al., 2015; Szczypka et al., 2005). A more recent study showed that inhibition of ferroptosis can protect kidneys from FA-induced AKI, implicating its important role in FA nephropathy (Martin-Sanchez et al., 2017). Additionally, mitochondrial dysfunction and early renal fibrosis, which are related to CKD pathology, can be found in the FA-induced AKI model, thus providing a new way in which to investigate AKI-CKD transition (Stallons et al., 2014).

Warfarin-induced AKI

A new model of warfarin-induced hematuric AKI based on 5/6 renal nephrectomized rats (Ware et al., 2011) was established to study the pathology of warfarin-related nephropathy (WRN) in patients with excessive anticoagulant (Rizk & Warnock, 2011). The 5/6 nephrectomy was performed in Sprague Dawley rats, with animals allowed three weeks recovery from the surgery before warfarin treatment. Warfarin was given orally via drinking water, and warfarin dosage was based on rat weight (Brodsky, 2014). Extensive glomerular hemorrhage and tubular obstruction can occur in rats after seven days administration of warfarin (0.4 mg/kg/d), as well as increased serum creatinine (Brodsky, 2014; Ozcan et al., 2012). Besides, WRN can also induce AKI, accelerate CKD, and increase the mortality rate in warfarin-treated patients (Brodsky et al., 2011). However, the mechanism and therapeutic strategies to ameliorate WRN-induced AKI remain to be demonstrated.

Glycerol-induced AKI

Rhabdomyolysis is a syndrome in which the breakdown of skeletal muscle leads to the release of intracellular proteins and toxic compounds into circulation (Hamel et al., 2015). AKI is a common complication of rhabdomyolysis and accounts for the high mortality (Elterman et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2012). Presently, oxidative damage and inflammation are the two major causes of rhabdomyolysis-induced AKI (Tomino, 2014). To reproduce the typical symptoms observed in humans, rats or mice are deprived of water for 24 h, after which a 8–10 mL/kg dose of 50% glycerol is administrated in the hindlimb muscle (Geng et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2014b). Although studies have reported that vitamin C (Ustundag et al., 2008), L-carnitine (Aydogdu et al., 2006; Ustundag et al., 2009), and resveratrol (Aydogdu et al., 2006) can ameliorate rhabdomyolysis-induced AKI, there is currently no effective therapy for this disease except aggressive rehydration (Gu et al., 2014).

Gentamicin nephropathy

Gentamicin is an aminoglycoside antibiotic commonly used to prevent gram-negative bacterial infection. Nevertheless, nephrotoxicity limits its use in clinical practice (He et al., 2015). Doses of gentamicin ranging from 40–200 mg/kg administered for 4–10 d (Bledsoe et al., 2008; Boroushaki et al., 2014; Heidarian et al., 2017; Jabbari et al., 2011) can induce acute renal failure in rats. Administration of 100 mg/kg i.p. for 5 d is recommended to mimic gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity (Hur et al., 2013; Stojiljkovic et al., 2008; Stojiljkovic et al., 2012). This acute model is characterized by increased levels of serum urea and creatinine, decreased GFR, tubular lesions, and fibrosis (Romero et al., 2009; Al-Shabanah et al., 2010; Balakumar et al., 2010).

CHRONIC KIDNEY DISEASE MODELS

CKD models mainly include diabetic/hypertensive nephropathy, glomerular injury, polycystic kidney disease (PKD), and chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis (Table 2). In this section, key information on various rodent models of CKD is discussed.

Table 2.

Advantages and disadvantages of experimental CKD mice models

| Pathology | Models | Advantages | Disadvantages | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Renal mass reduction | 5/6 nephrectomy (rats) | Mimics the progressive renal failure; after loss of renal mass in human | Highly influenced by back ground strains; surgery requires | Ergur et al., 2015; He et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2009 |

| Hypertension | SHR rats+UNX; angiotensin II infusion models | Highly relevant to hypertension nephropathy; useful to study AngII effect over kidney | Surgery requires; high cost; slow progression | Guo et al., 2015; Lankhorst et al., 2015; Zhong et al., 2016 |

| Diabetic nephropathy | Streptozotocin mice/rats; NOD mice BB-DP rat; ob/ob mice db/db mice; DBA/2J mice; STZ-eNOS-/-; db/db-eNOS/ mice | Gene modified; commercially available; available on multiple strains | No ideal model to mimics; diabetic nephropathy; expensive; some strains are infertile | Betz & Conway, 2014; Graham & Schuurman, 2015; Kitada et al., 2016; Ostergaard et al., 2017 |

| Primary glomerular nephropathy; focal segmental glomerulosclerosis | Adriamycin (rat, mice) models; Puromycin (rat) models | Widely used; induce podocyte injury | Highly depends on species and strains; toxic for most other cells | De Mik et al., 2013; Hakroush et al., 2014; Lee & Harris, 2011; Wada et al., 2016 |

| Crescentic glomerulonephritis | Nephrotoxic nephritis model; anti-GBM nephritis model | Similar to human Crescentic glomerulonephritis | Single symptom; difficult to induce | Borza & Hudson, 2002; Cheungpasitporn et al., 2016 |

| Membranous nephropathy | heymann nephritis rats; Cationic BSA mouse model | Widely used; identical pathology; marked proteinuria | Antigen (megalin) not found in human MN; limited experience | Cybulsky, 2011; Jefferson et al., 2010; Motiram Kakalij et al., 2016 |

| IgA nephropathy | ddY mouse, HIGA mice Uteroglobin-deficient mice CD89-transgenic mouse |

Reproduces human pathology; multiple models available | Mild disease development usually without progression towards end-stage renal disease | Eitner et al., 2010; Papista et al., 2015; Suzuki et al., 2014 |

| Secondary nephrotic syndrome; Amyloid A (AA) amyloidosis | Injection of chemical or biological compounds models | Widely used; reproduce features of human diseases | Rarely develop renal failure | Kisilevsky & Young, 1994; Teng et al., 2014 |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | NZB/NZW F1 mice MRL and CD95 mutants model |

Widely used; marked proteinuria | Incomplete features of SLE | Fagone et al., 2014; Nickerson et al., 2013; Otani et al., 2015 |

| Hereditary nephritis; polycystic kidney disease; Alport syndrome | pkd1 or pkd2 gene engineered mouse; COL4A43 gene knockout mouse | Widely used and useful to study PKD; major model; develop proteinuria and renal failure | Kashtan & Segal, 2011; Ko & Park, 2013; Korstanje et al., 2014; Ryu et al., 2012 |

Renal mass reduction

The remnant kidney model has been one of most commonly used experimental models of CKD. The 5/6 subtotal nephrectomy approach is widely used to mimic human CKD in rats. The right kidney is removed and the upper and lower poles (2/3 of the left kidney) are resected after ligation of the left renal artery (He et al., 2012). After surgery, activation of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) can cause glomerular hypertension/hyperfiltration (Ergür et al., 2015; Tapia et al., 2012). Together with oxidative stress and inflammation, the glomerular hypertension/hyperfiltration finally results in glomerulosclerosis, tubulointerstitial injury, renal atrophy, proteinuria, and possible ESRD (Gong et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2009). The remnant kidney model is highly influenced by the animal strain used. C57BL/6 mice are resistant to fibrosis or progressive CKD, whereas other animal strains such as rats and CD-1, 129/Sv, and Swiss-Webster mice are susceptible (Leelahavanichkul et al., 2010; Orlando et al., 2011). In addition, high mortality and little renal tissue after 5/6 nephrectomy are also challenges to this model.

Diabetic nephropathy

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is the leading cause of ESRD. There are many kinds of rodent models relevant to diabetic nephropathy, but none of them perfectly mimics the human disease (Deb et al., 2010). The Animal Models of Diabetic Complications Consortium (AMDCC) defines the ideal rodent model of human diabetic nephropathy and complications (Kong et al., 2013; Kitada et al., 2016). The latest validated criteria are: (1) more than 50% decrease in GFR; (2) greater than 10-fold increase in albuminuria compared with controls; and (3) pathological changes in kidneys including advanced mesangial matrix expansion±nodular sclerosis and mesangiolysis, glomerular basement membrane (GBM) thickening by >50% over baseline, arteriolar hyalinosis, and tubulointerstitial fibrosis. Classical type 1 diabetes can be modeled by the administration of streptozotocin (a toxin to β-cells that results in insulin deficiency), with spontaneous autoimmunity (e.g., NOD mice or BB-DP rat) or with gene mutation (Akita and OVE26 mice) (Graham & Schuurman, 2015; Kitada et al., 2016). A high fat diet is commonly used to induce obesity and insulin resistance and develop glomerular lesions in mice (Soler et al., 2012). Typical type 2 diabetes nephropathy (DN) model can be establised by leptin deficiency (e.g., ob/ob mice) or inactivation of the leptin receptor (e.g., db/db mice, Zuker rat) (Soler et al., 2012). To exhibit more pathological features of human DN, recent studies have focused on (1) targeted gene knockout in mice (e.g., eNOS-deficient mice (Takahashi & Harris, 2014)), (2) selection of more susceptible rodent species and strains (e.g., FVB (Chua et al., 2010) and DBA/2J mice (Østergaard et al., 2017), and (3) monogenic manipulations or superimposing additional key factors to accelerate nephropathy (e.g., STZ-eNOS-/-, db/db eNOS-/-) (Betz & Conway, 2014; Nakayama et al., 2009).

Hypertension-induced renal injury

Spontaneously hypertensive rats are usually used to investigate hypertension-induced nephropathy. Additionally, unilateral nephrectomy is required to promote significant renal injury with increased glomerular pressure and flow (Zhong et al., 2016). Chronic injection of angiotensin II for weeks also results in persistent hypertension and renal injury (Dikalov et al., 2014). Vascular endothelial growth factor (Lankhorst et al., 2015), Smad signaling (Liu & Davidson, 2012a), and inflammatory cytokines (Guo et al., 2015) are also involved in this process.

Primary glomerular nephropathy

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS)

FSGS is a common primary glomerular disorder characterized by podocyte injury and loss and marked proteinuria (Fogo, 2015). Although there is currently no primary FSGS model available, several secondary FSGS models have been established. Adriamycin (ADR) and puromycin are widely used to study FSGS. Single injection of these specific toxins can result in podocyte foot process effacement, deficient filtration barrier, and nephrotic syndrome (Fogo, 2003; Zhang et al., 2013). However, the dosage of adriamycin is highly dependent on species and strain. Most rat species are susceptible to low doses of ADR ranging from 1.5–7.5 mg/kg (Lee & Harris, 2011), whereas most mouse strains are resistant to ADR. To produce a successful model, higher doses of ADR are required, for example 9.8–12 mg/kg in male BALB/C (Wada et al., 2016) and 13–25 mg/kg in C57BL/c mice (Cao et al., 2010; Hakroush et al., 2014; Jeansson et al., 2009; Maimaitiyiming et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2000).

Gene modification approaches in mice, such as inactivation of Mpv-17 (Casalena et al., 2014; Viscomi et al., 2009), knockout α-actinin-4 (De Mik et al., 2013; Henderson et al., 2008) or NPHS2 (Mollet et al., 2009), or introducing the expression of Thy-1.1 antigen on podocytes, can also lead to proteinuria and FSGS (Smeets et al., 2004).

Crescentic glomerulonephritis

Antibodies fixation in the whole glomeruli (nephrotoxic nephritis) or GBM (anti-GBM nephritis) are the primary models used to mimic human crescentic glomerulonephritis (Hénique et al., 2014). Intraperitoneal injection of heterologous antibodies to heterologous whole glomeruli can induce nephrotoxic nephritis (Gigante et al., 2011). Anti-GBM nephritis can be caused by immunization with the non-collagenous domains of the alpha-3 chain of type IV collagen or passive transfer of anti-GBM antibodies (Cheungpasitporn et al., 2016; Kambham, 2012; Kvirkvelia et al., 2015). After treatment, severe proteinuria and azotemia appear in the following weeks.

Membranous nephropathy

Membranous nephropathy (MN) is a major cause of nephrotic syndrome in the elderly and is characterized by subepithelial deposits and diffuse thickening of the GBM (Makker & Tramontano, 2011). Active and passive Heymann nephritis model in rats closely resemble human MN and have been used to study MN (Sendeyo et al, 2013).

Autologous antibodies are exposed to target antigens by injection of kidney extracts or antiserum to antigen generated in another animal species (Cybulsky, 2011; Jefferson et al., 2010), resulting in immune deposits associated with heavy proteinuria (Cybulsky et al., 2005). In rat models, megalin and receptor associated protein (RAP) are the major podocyte antigens targeted by the circulating antibodies (Ronco & Debiec, 2010). However, studies have shown that megalin is neither expressed in human podocytes nor detected in patients with membranous nephropathy (Beck & Salant, 2010; Ma et al., 2013). Recently, M-type phospholipase A2 receptor (PLA2R) was identified as a target antigen for autoantibodies in human MN (Debiec & Ronco, 2011; Herrmann et al., 2012; Kao et al., 2015). Additionally, circulating thrombospondin type-1 domain-containing 7A (THSD7A) has been detected in a subgroup of patients with idiopathic MN rather than PLA2R, suggesting a new target antigen in human MN (Tomas et al., 2014).

The cationic BSA mouse model also produces features of human MN. Mice are preimmunized with cationic bovine serum albumin (cBSA) every other day for a week. Two weeks later, mice are reimmunized with cBSA in Freund’s adjuvant (Motiram Kakalij et al., 2016). Mice will develop symptoms of MN, including severe proteinuria, diffuse thickening of the GBM, subepithelial deposits, and GBM spikes.

IgA nephropathy (IgAN)

IgAN is the most common form of glomerulonephritis, and is characterized by mesangial immune complex depositions that contain IgA1, IgG, complement C3, and IgM (Daha & Van Kooten, 2016). Inducible IgAN models include intravenous injection of IgA containing immune complexes to develop mild and transient IgAN (Rifai et al., 1979), and oral administration of protein antigens that result in mesangial IgA deposits (Emancipator et al., 1983). The ddY mouse is a spontaneous IgAN model derived from a non-inbred strain that develops glomerulonephritis and mild proteinuria without hematuria (Suzuki et al., 2014). Mouse line HIGA, an inbred strain with high levels of circulating IgA, shows significant early-onset immune deposits (Eitner et al., 2010). Other genetically modified mice, such as uteroglobin-deficient mice (Lee et al., 2006) and CD89-transgenic mice (Moura et al., 2008; Papista et al., 2015), can also be used to investigate IgA nephropathy. Although some models are available, the underlying mechanism of IgAN is still not fully understood.

Secondary nephrotic syndrome

In this section, murine models of systemic lupus erythematosus and amyloidosis are reviewed. Transgenic murine models are widely used to investigate these complex diseases, especially systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Both MRL and CD95 gene mutant animals can serve as research models to develop SLE symptoms and investigate potential therapies.

Amyloid A (AA) amyloidosis

Amyloid A (AA) amyloidosis is a serious complication of chronic inflammation. AA-type amyloid deposition can cause alteration in tissue structure and function, with the kidney noted to be a major target organ (Simons et al., 2013). Injection of chemical or biological compounds such as casein, lipopolysaccharide (Kisilevsky & Young, 1994; Skinner et al., 1977), an extract of amyloidotic tissue or purified amyloidogenic light chains (Teng et al., 2014) are widely used to create AA amyloidosis mouse models. However, unlike clinical AA-amyloid patients, these models rarely develop renal failure (Simons et al., 2013). In recent years, a striking transgenic murine model has been developed. Mice carrying the human interleukin-6 gene under the control of the metallothionein-I promoter or with doxycycline-inducible transgenic expression of SAA provide another way to investigate AA-amyloid (Simons et al., 2013).

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

Lupus nephritis is characterized by autoantibodies against nuclear autoantigens such as DNA, histones, and nucleosomes (Liu & Davidson, 2012b). Most studies on SLE are based on murine models. Genetically modified models include MRL and CD95 mutants such as MRLlpr and FasLgld mice (Nickerson et al., 2013; Otani et al., 2015), BXSB mice (McGaha et al., 2005; McPhee et al., 2013), and NZB/NZW F1 mice (Fagone et al., 2014), which are widely used to develop proteinuria, lymphoproliferation, and similar features relevant to human lupus nephritis (McGaha & Madaio, 2014). Recently, TWEAK-Fn14 signaling has been reported to play an important role in the progression of lupus nephritis and anti-TWEAK blocking antibodies can preserve renal function and increase survival rate in experimental models of CKD (Gomez et al., 2016; Sanz et al., 2014). Although multiple mouse models have been used to investigate lupus nephritis, each model has limitations that impede our understanding of the pathogenesis and clinical manifestations of this disease. Subsequently, no effective therapy for lupus nephritis currently exists.

Hereditary nephritis

Polycystic kidney disease (PKD)

PKD includes a group of human monogenic disorders inherited in an autosomal dominant (ADPKD) or recessive (ARPKD) fashion. PKD is mainly restricted to the liver and kidney, and occurs in a range of ages from children to the elderly. In children and adults, ADPKD and ARPKD are the most common genetic nephropathies and leading causes of ESRD (Liebau & Serra, 2013). ADPKD is caused by mutation of either PKD1 (85%) or PKD2 (15%) (Kim et al., 2014a), whereas ARPKD is caused by PKHD1 gene mutations (Sweeney & Avner, 2011). Although hereditary PKD is complex and diverse, it is normally induced by single mutations in single genes. Therefore, genetically engineered murine models are widely used to mimic human PKD. As homozygous mice of PKD1 or PKD2 result in embryonic lethality (Woudenberg-Vrenken et al., 2009), conditional knockouts, inducible strategies, or the introduction of unstable alleles are the major ways to establish experimental models (Ko & Park, 2013). There have been some successful clinical trials based on results from these models. For example, tolvaptan has been proven to be effective in ADPKD and is now marketed in Japan (Torres et al., 2012). Moreover, combination therapy of tolvaptan and pasireotide has brought significant reduction in cystic and fibrotic volume in a PKD1 mouse model (Hopp et al., 2015).

Alport syndrome

Alport syndrome (AS) is a hereditary glomerulopathy resulting from mutations in the type IV collagen genes COL4A3, COL4A4, and COL4A5, and is characterized by hematuria, renal failure, hearing loss, ocular lesions (Savige et al., 2011), and abnormal collagen IV composition in the GBM (Savige et al., 2013). The COL4A43 gene knockout mouse is the major model used to study the pathogenesis of AS. Homozygous mice can develop proteinuria at 2–3 months of age and die from renal failure at 3–4 months (Kashtan & Segal, 2011). In COL4A43-/- mice, studies have shown that TNF-α contributes to Alport glomerulosclerosis by inducing podocyte apoptosis (Ryu et al., 2012). Furthermore, spontaneous COL4A4 mutation in NONcNZO recombinant inbred mice exhibits early stage proteinuria associated with glomerulosclerosis. These genetically modified mice provide valuable models for potential therapy testing and help understand the mechanisms of AS (Korstanje et al., 2014).

CONCLUSIONS

Although AKI and CKD are significantly increasing worldwide and cause high mortality, clinical diagnosis and therapeutic interventions are lagging. AKI-CKD transition and the underlying mechanisms of complex CKD such as IgA nephropathy, diabetic nephropathy, and FSGS are still unclear and impede the search for potential therapies. Despite the valuable new insights into kidney disease gained from existing models, many do not fully reproduce human clinical diseases. Thus, improved murine models are still desperately needed to investigate potential diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. In AKI models, obtaining new mouse strains susceptible to toxins/drugs is urgent, and finding new approaches to develop stable and reproducible AKI models is necessary. As for CKD models, to develop complex and specific pathologies, mice with multiple genetically modified will be widely used to develop complex and specific pathology in the near future. Additionally, models that faithfully develop common conditions such as DN or SLE are also imperative.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

Y.W.B wrote the manuscript with W.Q.L’s input. W.Q.L, Y.Y., and J.H.C. revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the General Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51309220, 31470776) and QianJiang Talent Plan to W.Q. Lin

REFERENCES

- Alobaidi R., Basu R.K., Goldstein S.L., Bagshaw S.M. Sepsis-associated acute kidney injury. Seminars in Nephrology. 2015;35(1):2–11. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shabanah O.A., Aleisa A.M., Al-Yahya A.A., Al-Rejaie S.S., Bakheet S.A., Fatani A.G., Sayed-Ahmed M.M. Increased urinary losses of carnitine and decreased intramitochondrial coenzyme a in gentamicin-induced acute renal failure in rats. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2010;25(1):69–76. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrassy K.M. Comments on 'KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease'. Kidney International. 2013;84(3):622–623. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreucci M., Faga T., Pisani A., Perticone M., Michael A. The ischemic/nephrotoxic acute kidney injury and the use of renal biomarkers in clinical practice. European Journal of Internal Medicine. 2017;39:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aydogdu N., Atmaca G., Yalcin O., Taskiran R., Tastekin E., Kaymak K. Protective effects of L-carnitine on myoglobinuric acute renal failure in rats. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology. 2006;33(1–2):119–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2006.04336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakumar P., Rohilla A., Thangathirupathi A. Gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity: Do we have a promising therapeutic approach to blunt it? Pharmacological Research. 2010;62(3):179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bander S.J., Buerkert J.E., Martin D., Klahr S. Long-term effects of 24-hr unilateral ureteral obstruction on renal function in the rat. Kidney International. 1985;28(4):614–620. doi: 10.1038/ki.1985.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudoux T.E.R., Pozdzik A.A., Arlt V.M., De Prez E.G., Antoine M.H., Quellard N., Goujon J.M., Nortier J.L. Probenecid prevents acute tubular necrosis in a mouse model of aristolochic acid nephropathy. Kidney International. 2012;82(10):1105–1113. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck L.H., Jr., Salant D.J. Membranous nephropathy: recent travels and new roads ahead. Kidney International. 2010;77(9):765–770. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz B., Conway B.R. Recent advances in animal models of diabetic nephropathy. Nephron Experimental Nephrology. 2014;126(4):191–195. doi: 10.1159/000363300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bledsoe G., Shen B., Yao Y.Y., Hagiwara M., Mizell B., Teuton M., Grass D., Chao L., Chao J.L. Role of tissue kallikrein in prevention and recovery of gentamicin-induced renal injury. Toxicological Sciences. 2008;102(2):433–443. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boroushaki M.T., Asadpour E., Sadeghnia H.R., Dolati K. Effect of pomegranate seed oil against gentamicin -induced nephrotoxicity in rat. Journal of Food Science and Technology. 2014;51(11):3510–3514. doi: 10.1007/s13197-012-0881-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borza D.B., Hudson B.G. Of mice and men: murine models of anti-GBM antibody nephritis. Kidney International. 2002;61(5):1905–1906. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun H., Schmidt B.M.W., Raiss M., Baisantry A., Mircea-Constantin D., Wang S.J., Gross M.L., Serrano M., Schmitt R., Melk A. Cellular senescence limits regenerative capacity and allograft survival. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2012;23(9):1467–1473. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011100967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky S.V. Anticoagulants and acute kidney injury: clinical and pathology considerations. Kidney Research and Clinical Practice. 2014;33(4):174–180. doi: 10.1016/j.krcp.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky S.V., Nadasdy T., Rovin B.H., Satoskar A.A., Nadasdy G.M., Wu H.M., Bhatt U.Y., Hebert L.A. Warfarin-related nephropathy occurs in patients with and without chronic kidney disease and is associated with an increased mortality rate. Kidney International. 2011;80(2):181–189. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Q., Wang Y.P., Zheng D., Sun Y., Wang Y., Lee V.W.S., Zheng G.P., Tan T.K., Ince J., Alexander S.I., Harris D.C.H. IL-10/TGF-β-modified macrophages induce regulatory T cells and protect against adriamycin nephrosis. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2010;21(6):933–942. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009060592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casalena G., Krick S., Daehn I., Yu L.P., Ju W.J., Shi S.L., Tsai S.Y., D'Agati V., Lindenmeyer M., Cohen C.D., Schlondorff D., Bottinger E.P. Mpv17 in mitochondria protects podocytes against mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis in vivo and in vitro. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology. 2014;306(11):F1372–F1380. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00608.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawla L.S., Kimmel P.L. Acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease: an integrated clinical syndrome. Kidney International. 2012;82(5):516–524. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawla L.S., Eggers P.W., Star R.A., Kimmel P.L. Acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease as interconnected syndromes. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;371(1):58–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1214243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.L., Hartono J.R., John R., Bennett M., Zhou X.J., Wang Y.X., Wu Q.Q., Winterberg P.D., Nagami G.T., Lu C.Y. Early interleukin 6 production by leukocytes during ischemic acute kidney injury is regulated by TLR4. Kidney International. 2011;80(5):504–515. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheungpasitporn W., Zacharek C.C., Fervenza F.C., Cornell L.D., Sethi S., Herrera Hernandez L.P., Nasr S.H., Alexander M.P. Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis due to coexistent anti-glomerular basement membrane disease and fibrillary glomerulonephritis. Clinical Kidney Journal. 2016;9(1):97–101. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfv126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier R.L., Forbes M.S., Thornhill B.A. Ureteral obstruction as a model of renal interstitial fibrosis and obstructive nephropathy. Kidney International. 2009;75(11):1145–1152. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua S., Jr., Li Y.F., Liu S.M., Liu R.J., Chan K.T., Martino J., Zheng Z.Y., Susztak K., D'Agati V.D., Gharavi A.G. A susceptibility gene for kidney disease in an obese mouse model of type II diabetes maps to chromosome 8. Kidney International. 2010;78(5):453–462. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung S., Yoon H.E., Kim S.J., Kim S.J., Koh E.S., Hong Y.A., Park C.W., Chang Y.S., Shin S.J. Oleanolic acid attenuates renal fibrosis in mice with unilateral ureteral obstruction via facilitating nuclear translocation of Nrf2. Nutrition & Metabolism. 2014;11(1):2. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-11-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cybulsky A.V. Membranous nephropathy. Contributions to Nephrology. 2011;169(1):107–125. doi: 10.1159/000313948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cybulsky A.V., Quigg R.J., Salant D.J. Experimental membranous nephropathy redux. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology. 2005;289(4):F660–F671. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00437.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Broe M.E. Chinese herbs nephropathy and Balkan endemic nephropathy: toward a single entity, aristolochic acid nephropathy. Kidney International. 2012;81(6):513–515. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Mik S.M., Hoogduijn M.J., De Bruin R.W., Dor F.J. Pathophysiology and treatment of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: the role of animal models. BMC Nephrology. 2013;14:74. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-14-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deb D.K., Sun T., Wong K.E., Zhang Z.Y., Ning G., Zhang Y., Kong J., Shi H., Chang A., Li Y.C. Combined vitamin D analog and AT1 receptor antagonist synergistically block the development of kidney disease in a model of type 2 diabetes. Kidney International. 2010;77(11):1000–1009. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debiec H., Ronco P. PLA2R autoantibodies and PLA2R glomerular deposits in membranous nephropathy. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;364(7):689–690. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1011678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejager L., Pinheiro I., Dejonckheere E., Libert C. Cecal ligation and puncture: the gold standard model for polymicrobial sepsis? Trends in Microbiology. 2011;19(4):198–208. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dendooven A., Ishola D.A., Jr., Nguyen T.Q., Van Der Giezen D.M., Kok R.J., Goldschmeding R., Joles J.A. Oxidative stress in obstructive nephropathy. International Journal of Experimental Pathology. 2011;92(3):202–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2010.00730.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lullo L., House A., Gorini A., Santoboni A., Russo D., Ronco C. Chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular complications. Heart Failure Reviews. 2015;20(3):259–272. doi: 10.1007/s10741-014-9460-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dikalov S.I., Nazarewicz R.R., Bikineyeva A., Hilenski L., Lassègue B., Griendling K.K., Harrison D.G., Dikalova A.E. Nox2-induced production of mitochondrial superoxide in angiotensin II-mediated endothelial oxidative stress and hypertension. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2014;20(2):281–294. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eitner F., Boor P., Floege J. Models of IgA nephropathy. Drug Discovery Today: Disease Models. 2010;7(1–2):21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ddmod.2010.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elterman J., Zonies D., Stewart I., Fang R., Schreiber M. Rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney injury in the injured war fighter. The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2015;79(4) Suppl 2:S171–S174. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emancipator S.N., Gallo G.R., Lamm M.E. Experimental IgA nephropathy induced by oral immunization. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1983;157(2):572–582. doi: 10.1084/jem.157.2.572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endre Z.H., Kellum J.A., Di Somma S., Doi K., Goldstein S.L., Koyner J.L., Macedo E., Mehta R.L., Murray P.T. Differential diagnosis of AKI in clinical practice by functional and damage biomarkers: workgroup statements from the tenth Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative Consensus Conference. Contributions to Nephrology. 2013;182:30–44. doi: 10.1159/000349964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endre Z.H., Pickering J.W., Walker R.J., Devarajan P., Edelstein C.L., Bonventre J.V., Frampton C.M., Bennett M.R., Ma Q., Sabbisetti V.S., Vaidya V.S., Walcher A.M., Shaw G.M., Henderson S.J., Nejat M., Schollum J.B.W., George P.M. Improved performance of urinary biomarkers of acute kidney injury in the critically ill by stratification for injury duration and baseline renal function. Kidney International. 2011;79(10):1119–1130. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ergür B.U., Çilaker M.S., Yilmaz O., Akokay P. The effects of α-lipoic acid on aortic injury and hypertension in the rat remnant kidney (5/6 nephrectomy) model. Anatolian Journal of Cardiology. 2015;15(6):443–449. doi: 10.5152/akd.2014.5483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagone P., Mangano K., Mammana S., Quattrocchi C., Magro G., Coco M., Imene S., Di Marco R., Nicoletti F. Acceleration of SLE-like syndrome development in NZBxNZW F1 mice by beta-glucan. Lupus. 2014;23(4):407–411. doi: 10.1177/0961203314522333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink M.P. Animal models of sepsis. Virulence. 2014;5(1):143–153. doi: 10.4161/viru.26083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogo A.B. Causes and pathogenesis of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nature Reviews Nephrology. 2015;11(2):76–87. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2014.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francoz C., Nadim M.K., Durand F. Kidney biomarkers in cirrhosis. Journal of Hepatology. 2016;65(4):809–824. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gall J.M., Wong V., Pimental D.R., Havasi A., Wang Z.Y., Pastorino J.G., Bonegio R.G.B., Schwartz J.H., Borkan S.C. Hexokinase regulates Bax-mediated mitochondrial membrane injury following ischemic stress. Kidney International. 2011;79(11):1207–1216. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng Y.Q., Zhang L., Fu B., Zhang J.R., Hong Q., Hu J., Li D.G., Luo C.J., Cui S.Y., Zhu F., Chen X.M. Mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate rhabdomyolysis-induced acute kidney injury via the activation of M2 macrophages. Stem Cell Research & Therapy. 2014;5(3):80. doi: 10.1186/scrt469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gigante M., Piemontese M., Gesualdo L., Iolascon A., Aucella F. Molecular and genetic basis of inherited nephrotic syndrome. International Journal of Nephrology. 2011;2011:792195. doi: 10.4061/2011/792195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez I.G., Roach A.M., Nakagawa N., Amatucci A., Johnson B.G., Dunn K., Kelly M.C., Karaca G., Zheng T.S., Szak S., Peppiatt-Wildman C.M., Burkly L.C., Duffield J.S. TWEAK-Fn14 Signaling Activates Myofibroblasts to Drive Progression of Fibrotic Kidney Disease. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2016;27(12):3639–3652. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015111227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong W., Mao S., Yu J., Song J.Y., Jia Z.J., Huang S.M., Zhang A.H. NLRP3 deletion protects against renal fibrosis and attenuates mitochondrial abnormality in mouse with 5/6 nephrectomy. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology. 2016;310(10):F1081–F1088. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00534.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham M.L., Schuurman H.J. Validity of animal models of type 1 diabetes, and strategies to enhance their utility in translational research. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2015;759:221–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu H.X., Yang M., Zhao X.M., Zhao B., Sun X.J., Gao X. Pretreatment with hydrogen-rich saline reduces the damage caused by glycerol-induced rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney injury in rats. Journal of Surgical Research. 2014;188(1):243–249. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z.T., Sun H., Zhang H.M., Zhang Y.F. Anti-hypertensive and renoprotective effects of berberine in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Clinical and Experimental Hypertension. 2015;37(4):332–339. doi: 10.3109/10641963.2014.972560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakroush S., Cebulla A., Schaldecker T., Behr D., Mundel P., Weins A. Extensive podocyte loss triggers a rapid parietal epithelial cell response. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2014;25(5):927–938. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013070687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamel Y., Mamoune A., Mauvais F.X., Habarou F., Lallement L., Romero N.B., Ottolenghi C., De Lonlay P. Acute rhabdomyolysis and inflammation. Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease. 2015;38(4):621–628. doi: 10.1007/s10545-015-9827-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J., Wang Y., Sun S., Yu M.N., Wang C.Y., Pei X.H., Zhu B., Wu J.Q., Zhao W.H. Bone marrow stem cells-derived microvesicles protect against renal injury in the mouse remnant kidney model. Nephrology. 2012;17(5):493–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2012.01589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L.Y., Peng X.F., Zhu J.F., Liu G.Y., Chen X., Tang C.Y., Liu H., Liu F.Y., Peng Y.M. Protective effects of curcumin on acute gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Canadian Journal of physiology and Pharmacology. 2015;93(4):275–282. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2014-0459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidarian E., Jafari-Dehkordi E., Valipour P., Ghatreh-Samani K., Ashrafi-Eshkaftaki L. Nephroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects of Pistacia atlantica leaf hydroethanolic extract against gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Journal of Dietary Supplements. 2017;14(5):489–502. doi: 10.1080/19390211.2016.1267062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson J.M., Al-Waheeb S., Weins A., Dandapani S.V., Pollak M.R. Mice with altered α-actinin-4 expression have distinct morphologic patterns of glomerular disease. Kidney International. 2008;73(6):741–750. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann S.M.S., Sethi S., Fervenza F.C. Membranous nephropathy: the start of a paradigm shift. Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension. 2012;21(2):203–210. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e32835026ed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesketh E.E., Czopek A., Clay M., Borthwick G., Ferenbach D., Kluth D., Hughes J. Renal ischaemia reperfusion injury: a mouse model of injury and regeneration. Journal of Visualized Experiments. 2014;(88) doi: 10.3791/51816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hénique C., Papista C., Guyonnet L., Lenoir O., Tharaux P.L. Update on crescentic glomerulonephritis. Seminars in Immunopathology. 2014;36(4):479–490. doi: 10.1007/s00281-014-0435-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopp K., Hommerding C.J., Wang X.F., Ye H., Harris P.C., Torres V.E. Tolvaptan plus pasireotide shows enhanced efficacy in a PKD1 model. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2015;26(1):39–47. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013121312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu R.K., Hsu C.Y. The role of acute kidney injury in chronic kidney disease. Seminars in Nephrology. 2016;36(4):283–292. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2016.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M.C., Shi M.J., Zhang J.N., Quiñones H., Kuro-O M., Moe O.W. Klotho deficiency is an early biomarker of renal ischemia-reperfusion injury and its replacement is protective. Kidney International. 2010;78(12):1240–1251. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L.P., Belousova T., Chen M.Y., Dimattia G., Liu D.J., Sheikh-Hamad D. Overexpression of stanniocalcin-1 inhibits reactive oxygen species and renal ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. Kidney International. 2012;82(8):867–877. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q.S., Niu Z.G., Tan J., Yang J., Liu Y., Ma H.J., Lee V.W.S., Sun S.M., Song X.F., Guo M.H., Wang Y.P., Cao Q. IL-25 elicits innate lymphoid cells and multipotent progenitor type 2 cells that reduce renal ischemic/reperfusion injury. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2015;26(9):2199–2211. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014050479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humanes B., Lazaro A., Camano S., Moreno-Gordaliza E., Lazaro J.A., Blanco-Codesido M., Lara J.M., Ortiz A., Gomez-Gomez M.M., Martin-Vasallo P., Tejedor A. Cilastatin protects against cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity without compromising its anticancer efficiency in rats. Kidney International. 2012;82(6):652–663. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hur E., Garip A., Camyar A., llgun S., Ozisik M., Tuna S., Olukman M., Narli Ozdemir Z., Yildirim Sozmen E., Sen S., Akcicek F., Duman S. The effects of vitamin d on gentamicin-induced acute kidney injury in experimental rat model. International Journal of Endocrinology. 2013;2013:313528. doi: 10.1155/2013/313528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabbari M., Rostami Z., Jenabi A., Bahrami A., Mooraki A. Simvastatin ameliorates gentamicin-induced renal injury in rats. Saudi Journal of Kidney Diseases and Transplantation: An Official Publication of the Saudi Center for Organ Transplantation, Saudi Arabia. 2011;22(6):1181–1186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeansson M., Björck K., Tenstad O., Haraldsson B. Adriamycin alters glomerular endothelium to induce proteinuria. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2009;20(1):114–122. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007111205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson J.A., Pippin J.W., Shankland S.J. Experimental models of membranous nephropathy. Drug Discovery Today: Disease Models. 2010;7(1–2):27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ddmod.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y., Liu R.J., Xie J.Y., Xiong H.B., He J.C., Chen N. Interleukin-10 deficiency aggravates kidney inflammation and fibrosis in the unilateral ureteral obstruction mouse model. Laboratory Investigation. 2013;93(7):801–811. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2013.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kambham N. Crescentic glomerulonephritis: an update on Pauci-immune and Anti-GBM diseases. Advances in Anatomic Pathology. 2012;19(2):111–124. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e318248b7a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao L., Lam V., Waldman M., Glassock R.J., Zhu Q.S. Identification of the immunodominant epitope region in phospholipase A2 receptor-mediating autoantibody binding in idiopathic membranous nephropathy. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2015;26(2):291–301. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013121315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karasawa T., Steyger P.S. An integrated view of cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity. Toxicology Letters. 2015;237(3):219–227. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2015.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashtan C.E., Segal Y. Glomerular basement membrane disorders in experimental models for renal diseases: impact on understanding pathogenesis and improving diagnosis. Contributions to Nephrology. 2011;169(1):175–182. doi: 10.1159/000313956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khwaja A. KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for acute kidney injury. Nephron. Clinical Practice. 2012;120(4):c179–C184. doi: 10.1159/000339789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H., Kang A.Y., Ko A.R., Park H.C., So I., Park J.H., Cheong H.I., Hwang Y.H., Ahn C. Calpain-mediated proteolysis of polycystin-1 C-terminus induces JAK2 and ERK signal alterations. Experimental Cell Research. 2014a;320(1):62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.J., Moradi H., Yuan J., Norris K., Vaziri N.D. Renal mass reduction results in accumulation of lipids and dysregulation of lipid regulatory proteins in the remnant kidney. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology. 2009;296(6):F1297–F1306. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90761.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.J., Lee J.S., Kim J.D., Cha H.J., Kim A., Lee S.K., Lee S.C., Kwon B.S., Mittler R.S., Cho H.R., Kwon B. Reverse signaling through the costimulatory ligand CD137L in epithelial cells is essential for natural killer cell-mediated acute tissue inflammation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109(1):E13–E22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112256109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.H., Lee D.W., Jung M.H., Cho H.S., Jeon D.H., Chang S.H., Park D.J. Macrophage depletion ameliorates glycerol-induced acute kidney injury in mice. Nephron. Experimental Nephrology. 2014b;128(1–2):21–29. doi: 10.1159/000365851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisilevsky R., Young I.D. Pathogenesis of amyloidosis. Baillière’s Clinical Rheumatology. 1994;8(3):613–626. doi: 10.1016/S0950-3579(05)80118-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitada M., Ogura Y., Koya D. Rodent models of diabetic nephropathy: their utility and limitations. International Journal of Nephrology and Renovascular Disease. 2016;9:279–290. doi: 10.2147/IJNRD.S103784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko J.W., Lee I.C., Park S.H., Moon C., Kang S.S., Kim S.H., Kim J.C. Protective effects of pine bark extract against cisplatin-induced hepatotoxicity and oxidative stress in rats. Laboratory Animal Research. 2014;30(4):174–180. doi: 10.5625/lar.2014.30.4.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko J.Y., Park J.H. Mouse models of polycystic kidney disease induced by defects of ciliary proteins. BMB Reports. 2013;46(2):73–79. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2013.46.2.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike K., Ueda S., Yamagishi S., Yasukawa H., Kaida Y., Yokoro M., Fukami K., Yoshimura A., Okuda S. Protective role of JAK/STAT signaling against renal fibrosis in mice with unilateral ureteral obstruction. Clinical Immunology. 2014;150(1):78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong L.L., Wu H., Cui W.P., Zhou W.H., Luo P., Sun J., Yuan H., Miao L.N. Advances in murine models of diabetic nephropathy. Journal of Diabetes Research. 2013;2013:797548. doi: 10.1155/2013/797548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korstanje R., Caputo C.R., Doty R.A., Cook S.A., Bronson R.T., Davisson M.T., Miner J.H. A mouse COL4A4 mutation causing Alport glomerulosclerosis with abnormal collagen α3α4α5(IV) trimers. Kidney International. 2014;85(6):1461–1468. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar D., Singla S.K., Puri V., Puri S. The restrained expression of NF-kB in renal tissue ameliorates folic acid induced acute kidney injury in mice. PLoS One. 2015;10(1):e115947. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvirkvelia N., McMenamin M., Gutierrez V.I., Lasareishvili B., Madaio M.P. Human anti-α3(IV)NC1 antibody drug conjugates target glomeruli to resolve nephritis. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology. 2015;309(8):F680–F684. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00289.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lankhorst S., Saleh L., Danser A.J., Van Den Meiracker A.H. Etiology of angiogenesis inhibition-related hypertension. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2015;21:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D.W., Kwak I.S., Lee S.B., Song S.H., Seong E.Y., Yang B.Y., Lee M.Y., Sol M.Y. Post-treatment effects of erythropoietin and nordihydroguaiaretic acid on recovery from cisplatin-induced acute renal failure in the rat. Journal of Korean Medical Science. 2009;24(Suppl 1):S170–S175. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2009.24.S1.S170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee V.W., Harris D.C. Adriamycin nephropathy: a model of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nephrology. 2011;16(1):30–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2010.01383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y.C., Zhang Z.J., Mukherjee A.B. Mice lacking uteroglobin are highly susceptible to developing pulmonary fibrosis. FEBS Letters. 2006;580(18):4515–4520. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leelahavanichkul A., Yan Q., Hu X.Z., Eisner C., Huang Y.N., Chen R., Mizel D., Zhou H., Wright E.C., Kopp J.B., Schnermann J., Yuen P.S.T., Star R.A. Angiotensin II overcomes strain-dependent resistance of rapid CKD progression in a new remnant kidney mouse model. Kidney International. 2010;78(11):1136–1153. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebau M.C., Serra A.L. Looking at the (w)hole: magnet resonance imaging in polycystic kidney disease. Pediatric Nephrology. 2013;28(9):1771–1783. doi: 10.1007/s00467-012-2370-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D.J., Shang H.P., Liu Y. Stanniocalcin-1 protects a mouse model from renal ischemia-reperfusion injury by affecting ROS-mediated multiple signaling pathways. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2016a;17(7):1051. doi: 10.3390/ijms17071051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Abdel-Razek O., Liu Z.Y., Hu F.Q., Zhou Q.S., Cooney R.N., Wang G.R. Role of surfactant proteins A and D in sepsis-induced acute kidney injury. Shock. 2015a;43(1):31–38. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Song Y.J., Zhao M., Yi Z.W., Zeng Q.Y. Protective effects of edaravone, a free radical scavenger, on lipopolysaccharide-induced acute kidney injury in a rat model of sepsis. International Urology and Nephrology. 2015b;47(10):1745–1752. doi: 10.1007/s11255-015-1070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Wang N., Wei G., Fan S.J., Lu Y.L., Zhu Y.F., Chen Q., Huang M., Zhou H., Zheng J. Consistency and pathophysiological characterization of a rat polymicrobial sepsis model via the improved cecal ligation and puncture surgery. International Immunopharmacology. 2016b;32:66–75. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2015.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Davidson A. Taming lupus-a new understanding of pathogenesis is leading to clinical advances. Nature Medicine. 2012a;18(6):871–882. doi: 10.1038/nm.2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Huang X.R., Lan H.Y. Smad3 mediates ANG II-induced hypertensive kidney disease in mice. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology. 2012b;302(8):F986–F997. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00595.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L.H., Oh D.J., Dursun B., He Z., Hoke T.S., Faubel S., Edelstein C.L. Increased macrophage infiltration and fractalkine expression in cisplatin-induced acute renal failure in mice. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2008;324(1):111–117. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.130161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luyckx V.A., Bertram J.F., Brenner B.M., Fall C., Hoy W.E., Ozanne S.E., Vikse B.E. Effect of fetal and child health on kidney development and long-term risk of hypertension and kidney disease. The Lancet. 2013;382(9888):273–283. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60311-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H., Sandor D.G., Beck L.H., Jr. The role of complement in membranous nephropathy. Seminars in Nephrology. 2013;33(6):531–542. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maimaitiyiming H., Zhou Q., Wang S.X. Thrombospondin 1 deficiency ameliorates the development of adriamycin-induced proteinuric kidney disease. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0156144. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makker S.P., Tramontano A. Idiopathic membranous nephropathy: an autoimmune disease. Seminars in Nephrology. 2011;31(4):333–340. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik S., Suchal K., Gamad N., Dinda A.K., Arya D.S., Bhatia J. Telmisartan ameliorates cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity by inhibiting MAPK mediated inflammation and apoptosis. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2015;748:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchant V., Droguett A., Valderrama G., Burgos M.E., Carpio D., Kerr B., Ruiz-Ortega M., Egido J., Mezzano S. Tubular overexpression of Gremlin in transgenic mice aggravates renal damage in diabetic nephropathy. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology. 2015;309(6):F559–F568. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00023.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Sanchez D., Ruiz-Andres O., Poveda J., Carrasco S., Cannata-Ortiz P., Sanchez-Niño M.D., Ortega M.R., Egido J., Linkermann A., Ortiz A., Sanz A.B. Ferroptosis, but not necroptosis, is important in nephrotoxic folic acid-induced AKI. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2017;28(1):218–229. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015121376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui K., Kamijo-Ikemorif A., Sugaya T., Yasuda T., Kimura K. Renal liver-type fatty acid binding protein (L-FABP) attenuates acute kidney injury in aristolochic acid nephrotoxicity. The American Journal of Pathology. 2011;178(3):1021–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGaha T.L., Madaio M.P. Lupus nephritis: animal modeling of a complex disease syndrome pathology. Drug Discovery Today: Disease Models. 2014;11:13–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ddmod.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGaha T.L., Sorrentino B., Ravetch J.V. Restoration of tolerance in lupus by targeted inhibitory receptor expression. Science. 2005;307(5709):590–593. doi: 10.1126/science.1105160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPhee C.G., Bubier J.A., Sproule T.J., Park G., Steinbuck M.P., Schott W.H., Christianson G.J., Morse H.C., III, Roopenian D.C. IL-21 is a double-edged sword in the systemic lupus erythematosus-like disease of BXSB. Yaa mice. The Journal of Immunology. 2013;191(9):4581–4588. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitazaki S., Kato N., Suto M., Hiraiwa K., Abe S. Interleukin-6 deficiency accelerates cisplatin-induced acute renal failure but not systemic injury. Toxicology. 2009;265(3):115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollet G., Ratelade J., Boyer O., Muda A.O., Morisset L., Lavin T.A., Kitzis D., Dallman M.J., Bugeon L., Hubner N., Gubler M.C., Antignac C., Esquivel E.L. Podocin inactivation in mature kidneys causes focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and nephrotic syndrome. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2009;20(10):2181–2189. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009040379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morsy M.A., Heeba G.H. Nebivolol ameliorates cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology. 2016;118(6):449–455. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.12538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motiram Kakalij R., Tejaswini G., Patil M.A., Dinesh Kumar B., Diwan P.V. Vanillic acid ameliorates cationic bovine serum albumin induced immune complex glomerulonephritis in BALB/c mice. Drug Development Research. 2016;77(4):171–179. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moura I.C., Benhamou M., Launay P., Vrtovsnik F., Blank U., Monteiro R.C. The glomerular response to IgA deposition in IgA nephropathy. Seminars in Nephrology. 2008;28(1):88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama T., Sato W., Kosugi T., Zhang L., Campbell-Thompson M., Yoshimura A., Croker B.P., Johnson R.J., Nakagawa T. Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology. 2009;296(2):F317–F327. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90450.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson K.M., Cullen J.L., Kashgarian M., Shlomchik M.J. Exacerbated autoimmunity in the absence of TLR9 in MRL.Faslpr mice depends on Ifnar1. The Journal of Immunology. 2013;190(8):3889–3894. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nortier J., Pozdzik A., Roumeguere T., Vanherweghem J.L. [Aristolochic acid nephropathy ("Chinese herb nephropathy")] Nephrologie & Therapeutique. 2015;11(7):574–588. doi: 10.1016/j.nephro.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlando L.A., Belasco E.J., Patel U.D., Matchar D.B. The chronic kidney disease model: a general purpose model of disease progression and treatment. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making. 2011;11:41. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-11-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz A., Sanchez-Niño M.D., Izquierdo M.C., Martin-Cleary C., Garcia-Bermejo L., Moreno J.A., Ruiz-Ortega M., Draibe J., Cruzado J.M., Garcia-Gonzalez M.A., Lopez-Novoa J.M., Soler M.J., Sanz A.B. Translational value of animal models of kidney failure. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2015;759:205–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otani Y., Ichii O., Otsuka-Kanazawa S., Chihara M., Nakamura T., Kon Y. MRL/MpJ-Faslpr mice show abnormalities in ovarian function and morphology with the progression of autoimmune disease. Autoimmunity. 2015;48(6):402–411. doi: 10.3109/08916934.2015.1031889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozcan A., Ware K., Calomeni E., Nadasdy T., Forbes R., Satoskar A.A., Nadasdy G., Rovin B.H., Hebert L.A., Brodsky S.V. 5/6 nephrectomy as a validated rat model mimicking human warfarin-related nephropathy. American Journal of Nephrology. 2012;35(4):356–364. doi: 10.1159/000337918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozkok A., Edelstein C.L. Pathophysiology of cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury. BioMed Research International. 2014;2014:967826. doi: 10.1155/2014/967826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Østergaard M.V., Pinto V., Stevenson K., Worm J., Fink L.N., Coward R.J.M. DBA2J db/db mice are susceptible to early albuminuria and glomerulosclerosis that correlate with systemic insulin resistance. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology. 2017;312(2):F312–F321. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00451.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pálsson R., Patel U.D. Cardiovascular complications of diabetic kidney disease. Advances in Chronic Kidney Disease. 2014;21(3):273–280. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pannu N. Bidirectional relationships between acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease. Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension. 2013;22(3):351–356. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e32835fe5c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papista C., Lechner S., Ben Mkaddem S., Lestang M.B., Abbad L., Bex-Coudrat J., Pillebout E., Chemouny J.M., Jablonski M., Flamant M., Daugas E., Vrtovsnik F., Yiangou M., Berthelot L., Monteiro R.C. Gluten exacerbates IgA nephropathy in humanized mice through gliadin-CD89 interaction. Kidney International. 2015;88(2):276–285. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng W.H., Chen J.H., Jiang Y.G., Wu J.Y., Shou Z.F., He Q., Wang Y.M., Chen Y., Wang H.P. Urinary fractalkine is a marker of acute rejection. Kidney International. 2008;74(11):1454–1460. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poli-De-Figueiredo L.F., Garrido A.G., Nakagawa N., Sannomiya P. Experimental models of sepsis and their clinical relevance. Shock. 2008;30(Suppl 1):53–59. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318181a343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh G., Ranganathan P. Singh S., Coppola V. Mouse Genetics. Vol. 1194. Humana Press; New York, NY: 2014. Mouse models and methods for studying human disease, acute kidney injury (AKI) pp. 421–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rifai A., Small P.A., Jr., Teague P.O., Ayoub E.M. Experimental IgA nephropathy. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1979;150(5):1161–1173. doi: 10.1084/jem.150.5.1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizk D.V., Warnock D.G. Warfarin-related nephropathy: another newly recognized complication of an old drug. Kidney International. 2011;80(2):131–133. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero F., Pérez M., Chávez M., Parra G., Durante P. Effect of uric acid on gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats - role of matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology. 2009;105(6):416–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2009.00466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronco P., Debiec H. Antigen identification in membranous nephropathy moves toward targeted monitoring and new therapy. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2010;21(4):564–569. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009121220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]