Abstract

Background

The production of recombinant proteins with proper conformation, appropriate post-translational modifications in an easily scalable and cost-effective system is challenging. Lactococcus lactis has recently been identified as an efficient Gram positive cell factory for the production of recombinant protein. We and others have used this expression host for the production of selected malaria vaccine candidates. The safety of this production system has been confirmed in multiple clinical trials. Here we have explored L. lactis cell factories for the production of 31 representative Plasmodium falciparum antigens with varying sizes (ranging from 9 to 90 kDa) and varying degree of predicted structural complexities including eleven antigens with multiple predicted structural disulfide bonds, those which are considered difficult-to-produce proteins.

Results

Of the 31 recombinant constructs attempted in the L. lactis expression system, the initial expression efficiency was 55% with 17 out of 31 recombinant gene constructs producing high levels of secreted recombinant protein. The majority of the constructs which failed to produce a recombinant protein were found to consist of multiple intra-molecular disulfide-bonds. We found that these disulfide-rich constructs could be produced in high yields when genetically fused to an intrinsically disorder protein domain (GLURP-R0). By exploiting the distinct biophysical and structural properties of the intrinsically disordered protein region we developed a simple heat-based strategy for fast purification of the disulfide-rich protein domains in yields ranging from 1 to 40 mg/l.

Conclusions

A novel procedure for the production and purification of disulfide-rich recombinant proteins in L. lactis is described.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12934-018-0902-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Plasmodium falciparum, Malaria, Disulfide-rich protein, Merozoite antigens, Lactococcus lactis

Background

Protein production is often the limiting factor in research and development of vaccines, sero-diagnostic tools, and immuno-assays. The yield, purity and cost of production are some of the important parameters which determine the choice of expression system for recombinant protein production. There is no single system, which can accommodate all recombinant proteins, and if successful, expression yields vary by orders of magnitudes due to biophysical and structural properties of the recombinant proteins. Of the different proteins, the production of homogenously folded disulfide bonded proteins have been particularly challenging [1, 2]. The lactic acid bacteria Lactococcus lactis has gained importance as a host for heterologous protein expression [3–7] because (1) it can export the recombinant protein into the culture supernatant from where it can be readily purified, (2) it is a Gram positive bacteria which does not produce endotoxins, (3) unwanted glycosylation of proteins has not been described, and (4) it is ‘generally recognized as safe’ (GRAS). The L. lactis expression system is compatible with large-scale upstream and downstream processes and therefore provides a low cost production system. The safety of this expression system has been demonstrated in humans (reviewed in [8, 9]). Recently, we have reported use of L. lactis for successful production of recombinant Pfs48/45, a disulfide-rich malaria transmission blocking vaccine candidate from Plasmodium falciparum, which has been difficult to produce as recombinant protein with correct conformation using a variety of other prokaryotic as well as eukaryotic recombinant protein expression systems.

In this study we have further demonstrated the suitability of L. lactis for expression and purification of a panel of 31 recombinant proteins from 25 distinct antigens of P. falciparum (non-overlapping sub-domains from some antigens were expressed separately to study their distinct antigenic properties) as several of which consist multiple structural disulfide bonds. Proper disulfide bond formation of the recombinant antigens is essential for not only the native structure and its antigenic property but also for inducing appropriate innate and adaptive immune responses. The antigens selected in this study are localized in diverse sub-cellular compartments of the merozoite, the transient extracellular stage of the asexual blood stage of P. falciparum, which is highly specialized for erythrocyte invasion [10, 11]. These include the integral merozoite membrane proteins, the associated peripheral surface proteins and proteins secreted from the various secretory organelles such as the micronemes, rophtries and the dense granules which are understood to form functional complexes with merozoite surface proteins [12]. Together these merozoite surface protein complexes play important roles in erythrocyte invasion and several of them have been identified as putative targets of protective immunity against malaria [13]. The panel of malaria antigens selected in this present study covers a variety of protein structural complexities, ranging from proteins predicted to have a highly disordered structure to those consisting of multiple (2–75) cysteine residues predicted to form structural disulfide bonds determining the overall secondary and tertiary structure of the respective proteins. The panel of malaria antigens consists of merozoite antigens which are targets of (1) naturally acquired immunity, (2) functional antibodies, and (3) include both variable and conserved regions of the respective antigens. We show that L. lactis is an efficient system for expression of recombinant malaria antigens with a variety of protein structural complexities.

Results

Protein expression

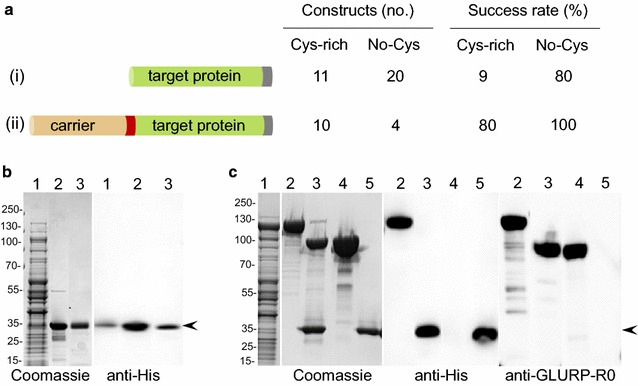

A panel of P. falciparum proteins targeted by naturally acquired immune responses was produced as C-terminally His-tagged proteins in L. lactis MG1363 (Fig. 1a(i)). Sub-domains of some malaria antigens representing the variable and conserved regions (such as from MSP2 to MSP3) were expressed as separate recombinant proteins to allow detection of both allele-specific and cross-reactive antibodies (Table 1). The success of recombinant protein production from the respective L. lactis clone was determined (as Low, Medium or High) as per the yield of the secreted recombinant protein purified from a batch fermentation of 1 l. We observed an overall efficiency of 55% with 17 out of 31 recombinant clones producing a secreted recombinant protein as detected by SDS-PAGE and Western Blot analysis (Table 1). The success rate was much higher (80%) for recombinant proteins which lacked cysteine residues (expression was detected for 16 out of 20 such recombinant proteins). However, the success rate was lower (9%) for those recombinant proteins containing two or more cysteine residues (expression was detected for only 1 out of 11 recombinant proteins). In general, expression constructs which produced high yields of recombinant proteins were low in cysteine residues and relatively unstructured (Additional file 1a). In contrast, neither the iso-electric point (pI) nor the molecular weight of the cloned expression construct seemed to affect its expression level in L. lactis (Additional file 1b). We therefore speculated that increasing the overall disorder score of the difficult-to-express proteins by creating a fusion protein with an unstructured protein domain might enhance the yield of the desired recombinant protein. Accordingly, constructs which failed to produce a recombinant protein were genetically linked to an unstructured carrier protein (the R0 sub-domain of the GLURP antigen) (Fig. 1a(ii)). A TEV protease cleavage site was inserted in the fusion-junction to allow removal of the R0 carrier protein. Twelve out of fourteen fusion recombinant constructs thus designed, showed higher expression levels compared to the respective target proteins expressed without fusion with the disordered carrier protein (Fig. 1a). Two constructs with large number of cysteine residues and highly complex predicted secondary structure (EBA140RII and RIPR containing 23 and 75 cysteine residues, respectively) did not show improvement in their expression levels despite their fusion with the carrier protein.

Fig. 1.

Expression and Purification of target recombinant proteins in L. lactis. a Left panel: Schematic representation for cloning and expression of target recombinant proteins from P. falciparum antigens without (i) and with (ii) carrier fusion protein; Right panel: Classification of the target recombinant proteins based on their cysteine content (constructs containing two or more cysteine residues are classified as cysteine-rich proteins) and the overall success rates for production of target recombinant proteins by the respective L. lactis expression clones using strategy (i) or (ii). b Expression and purification of recombinant cMSP33D7 (a representative recombinant protein which does not contain cysteine residues and expressed successfully in L. lactis without carrier fusion protein); Left panel: Coomassie blue-stained non-reducing SDS-PAGE analysis showing purification of recombinant cMSP33D7protein secreted in L. lactis culture supernatant; Lane 1: raw culture supernatant, lane 2: Ni+-NTA purified cMSP33D7; lane 3: Ion-exchange purified cMSP33D7; Right panel: Western Blot analysis of recombinant cMSP33D7 using anti-His antibody. c Expression and purification of recombinant R0-MSPDBL2 (a representative cysteine-rich recombinant protein and which was expressed successfully in L. lactis with GLURP-R0 as a carrier fusion protein); Left panel: Coomassie blue-stained non-reducing SDS-PAGE analysis showing purification of recombinant R0-MSPDBL2 protein secreted in L. lactis culture supernatant; Middle panel: Western blot analysis of recombinant R0-MSPDBL2 using anti-His antibody; and Right panel: Western blot analysis of recombinant R0-MSPDBL2 using anti-GLURP-R0 antibody; Lane 1: raw culture supernatant; lane 2: Affinity purified R0-MSPDBL2 recombinant protein; lane 3: TEV cleavage of recombinant R0-MSPDBL2 and SDS-PAGE separation of R0 and MSPDBL2 fragments; Lane 4: Ion-exchange chromatography separates cleaved R0 carrier protein after TEV protease cleavage and Lane 5: Purified recombinant MSPDBL2 obtained after TEV cleavage and ion-exchange chromatography. The arrow-heads indicate positions of cMSP33D7 and MSPDBL2 recombinant proteins in respective panels. Numbers shown on the left hand side of the gel pictures represent positions of protein molecular weight markers in kDa

Table 1.

Characteristics and purification strategies of recombinant proteins

| Antigena | Accession number | Target sequence | Cysteine (no) | Disorder tendencyb | Expression level | Capturing | Polishing | Mass (Da) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No carrier | With carrier | IMAC | Heat | IEC | Yield (mg/l)c | Calculated | Observedd | |||||

| GPI-anchored | ||||||||||||

| MSP119k | PFI1475W | N1607–N1702 | 12 | 0 | High | X | A | 30 | 12.2 | 15 | ||

| MSP23D7 | PFB0300C | A111–G238 | 0 | 100 | High | X | A | 20 | 13.7 | 40 | ||

| MSP2FC27 | E143–G230 | 0 | 94 | High | X | A | 20 | 9.6 | 25 | |||

| Pf12 | PFF0615C | K155–S323 | 6 | 0 | Low | Med | X | C | 10 | 20 | 20 | |

| Pf38 | PFE0395C | K139–I327 | 6 | 0 | Low | Med | X | C | 10 | 23 | 25 | |

| Peripherally associated | ||||||||||||

| nMSP33D7 | PF10_0345 | N21–L182 | 1 | 25 | High | X | A | 40 | 17.6 | 27 | ||

| cMSP33D7 | PF10_0345 | K183–H354 | 0 | 0 | High | X | A | 18 | 20 | 30 | ||

| nMSP3K1 | PFU08851 | N21–L208 | 0 | 48 | High | X | A | 35 | 21 | 37 | ||

| MSP6 | PF10_346 | Y17–N160 | 0 | 70 | Med | X | A | 10 | 17.5 | 23 | ||

| MSP3.3 | PF10_0347 | Q23–T227 | 0 | 48 | Med | X | A | 7 | 22.3 | 37 | ||

| MSP3.7 | PF10_0352 | K27–R213 | 0 | 100 | Med | X | A | 7 | 20.9 | 37 | ||

| GLURP-R0 | AAA50613 | T27–A500 | 0 | 99 | High | X | A | 75 | 54.3 | 90 | ||

| GLURP-R2 | AAA50613 | V705–1177 | 0 | 78 | High | X | A | 35 | 53 | 110 | ||

| SERA5 | PF02_0072 | K17–192/226–S382 | 8 | 40 | Low | High | X | C | 17 | 35.5 | 38 | |

| Pf41 | PFD0240C | S231–S378 | 6 | 0 | Low | Med | X | C | 7 | 18 | 18 | |

| MSPDBL1 | PF10_0348 | K143–D443 | 13 | 0 | Low | Med | X | C | 8 | 37 | 37 | |

| MSPDBL2 | PF10_0355 | K161–L457 | 12 | 0 | Low | High | X | C | 15 | 36.5 | 35 | |

| MSPDBL1 (Leucine) | PF10_0348 | D508–K697 | 0 | 69 | Med | X | A | 7 | 22 | 35 | ||

| Micronemal/microneme | ||||||||||||

| EBA140RIII–V | MAL13P1.60 | E746–T1045 | 0 | 93 | High | X | A | 16 | 32.9 | 40 | ||

| EBA140 RII | MAL13P1.60 | Q146–K710 | 23 | 0 | Low | Low | X | C | 1,5 | 67.3 | 85 | |

| GAMA | PF08_0008 | N25–H337 | 7 | 10 | Low | Med | X | A | 5 | 36.8 | 45 | |

| RIPR | PFC1045C | K279–D995 | 75 | 0 | Low | Low | X | A | 1 | 82.3 | 110 | |

| SUB2 | PF11_0381 | K14–N681 | 2 | 29 | Low | Med | X | A | 5 | 78.3 | 90 | |

| Rhoptry | ||||||||||||

| PfRh2b | MAL13P1.176 | L2790–K3184 | 0 | 91 | Med | X | A | 8 | 44.7 | 120 | ||

| PfRh2a | PF13_0198 | H2874–S3060 | 0 | 26 | High | X | A | 13 | 22 | 25 | ||

| PfRh4.2 | PFD1150C | L1275–I1451 | 0 | 11 | Low | Med | X | C | 2 | 21.5 | 21 | |

| PfRh2-2030 | PF13_0198 | E2030–Q2528 | 1 | 0 | Med | X | A | 8 | 58 | 58 | ||

| RAMA | MAL7P1.208 | I42–N786 | 0 | 100 | Low | Med | X | A | 7 | 90.6 | 120 | |

| RALP-1 | MAL7P1.119 | N396–P634 | 0 | 47 | Low | Med | X | A | 10 | 27 | 37 | |

| RON2 | PF14_0495 | I775–K958 | 0 | 49 | Med | X | A | 10 | 24 | 25 | ||

| RON4 | PF11_0168 | K25–L709 | 0 | 100 | Low | Med | X | A | 9 | 76 | 150 | |

A anion exchange (HiTrap Q HP); C cation exchange (Hitrap SP HP)

aGene originate from 3D7 unless otherwise stated

bDisorder prediction score was calculated by using IUPred [41]

cThe levels of expressed protein was determined by BCA kit after final step purification. Expression levels are grouped into “low” (0.1–2 mg/l), “medium” (2–10 mg/l), and “high” (> 10 mg/l)

dBy SDS-PAGE

Protein purification

A simple workflow was developed consisting of batch-fermentation and a 2-step downstream purification process. Recombinant proteins from L. lactis expressing clones were secreted in the culture medium and harvested by separation of cellular biomass through centrifugation and affinity purified through the His-tag using HisTrap HP-column. Upon elution the fractions containing the recombinant protein were collectively subjected to a polishing step using ion-exchange chromatography to further remove contaminating host-cell-protein (HCP). Using this approach a highly purified recombinant protein was obtained as exemplified with recombinant cMSP33D7 (Fig. 1b). Recombinant proteins expressed with R0-fusion partner were harvested from the clarified culture medium using the same procedure as described above and exemplified with recombinant R0-MSPDBL2 (Fig. 1c). The affinity purified fusion protein (Fig. 1c, lane 2) was cleaved with the TEV protease (Fig. 1c, lane 3) before being purified further with ion-exchange chromatography column (Table 1) to separate HCP, TEV, and the R0-fusion partner (Fig. 1c, lane 4) from the target recombinant protein (Fig. 1c, lane 5). The identity and purity of the target protein was confirmed at each step by immune blotting with antibodies against the His-tag and R0 to demonstrate removal of the carrier protein (Fig. 1b, c).

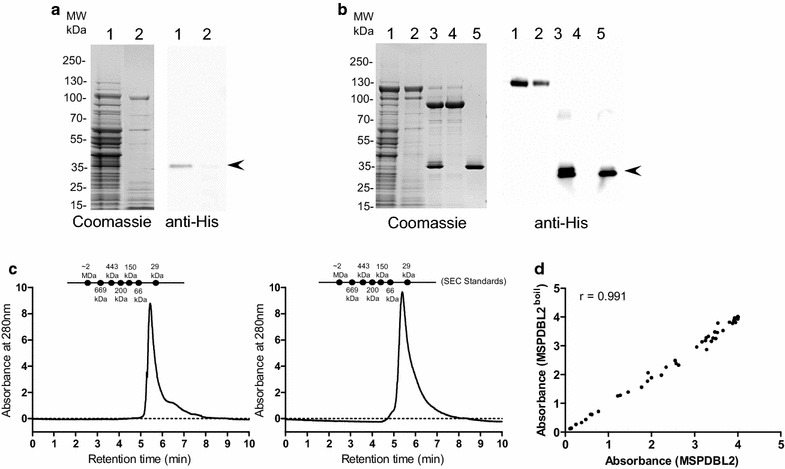

GLURP stabilizes structural domains against thermal denaturation

The GLURP-R0 region is highly disordered as predicted by the IUPred software and is characterized to have low hydrophobicity and high net charge (Table 1). It migrates on SDS-PAGE with an apparent molecular mass more than twofold higher than its predicted molecular mass. Disordered proteins are often heat-resistant [14] and since boiling has been used as a strategy to purify similarly disordered recombinant epsin 1 and AP180 [15], we speculated that GLURP-R0 might stabilize its fusion partners against thermal denaturation. In a first experiment, we cultured the MSPDBL2 construct without (Fig. 2a) and with (Fig. 2b) a R0-fusion partner. Boiling of culture supernatants from the batch fermentation of recombinant clones expressing R0-fusion constructs and its immediate cooling in an ice-bath resulted in the denaturation of > 80% of the HCP, which was subsequently removed by centrifugation (Fig. 2a, b, lane 2). The MSPDBL2 recombinant protein did not resist heat-treatment (Fig. 2a, lane 2) whereas the R0-MSPDBL2 fusion protein remained in solution under these conditions (Fig. 2b, lane 2). The supernatant containing R0-MSPDBL2 was incubated with the TEV protease (Fig. 2b, lane 3) and the resulting mixture was subjected to purification through ion-exchange chromatography column to separate TEV-protease, R0-fusion partner and HCP (Fig. 2b, lane 4) from the target protein (Fig. 2b, lane 5). The integrity of the resulting MSPDBL2-domain was examined by SE-HPLC and ELISA. For comparison, recombinant MSPDBL2 purified without heat-treatment was included in the analysis. The two MSPDBL2 recombinant proteins migrated with similar retention times of 5.54 min by SE-HPLC (Fig. 2c) suggesting that heat treatment did not affect protein-stability and multimerization. The two MSPDBL2 protein preparations also showed similar antigenicity profiles against sera from malaria-immune individuals suggesting that the overall protein structure of the cysteine-rich DBL2 domain is unaffected by the heat-treatment (Fig. 2d). Next, we applied the same heat-treatment and purification procedure to the remaining nine R0-fusion proteins (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Purification of target recombinant protein by heat-treatment. a Heat treatment of L. lactis raw culture supernatant expressing recombinant MSPDBL2; Left panel: Coomassie blue stained SDS-PAGE analysis of MSPDBL2 containing supernatant before (lane 1) and after (lane 2) heat treatment; Right panel: Corresponding Western blot probed with anti-His antibodies. b Heat treatment of L. lactis raw culture supernatant expressing R0-MSPDBL2 fusion protein; Left panel: Coomassie blue stained SDS-PAGE analysis of R0-MSPDBL2 containing culture supernatant before (lane 1) and after (lane 2) heat treatment; lane 3: TEV protease treatment of recombinant R0-MSPDBL2 and ion-exchange chromatography based separation of R0 fusion partner (lane 4) and MSPDBL2 (lane 5) fragments after TEV protease cleavage of R0-MSPDBL2 derived from heat treated culture supernatant; Right panel: Corresponding Western blot probed with anti-His antibodies. The arrow-heads indicate the position of MSPDBL2 fragment. c Size exclusion chromatography analysis of purified recombinant MSPDBL2 as obtained from L. lactis culture supernatants expressing R0-MSPDBL2 (left panel) and MSPDBL2 expressed without carrier fusion partner (right panel). SE-HPLC was performed under native conditions in a phosphate buffer pH 7.2 to determine the amount of monomer in the sample. d Comparative antigenicity assessment of purified recombinant MSPDBL2 protein. The scatter-plot shows Pearson’s co-relation coefficient between the ELISA values observed for reactivity of a panel of 54 malaria hyperimmune Liberian sera samples against the recombinant MSPDBL2 protein preparations purified by heat treatment (y-axis) or without heat (x-axis)

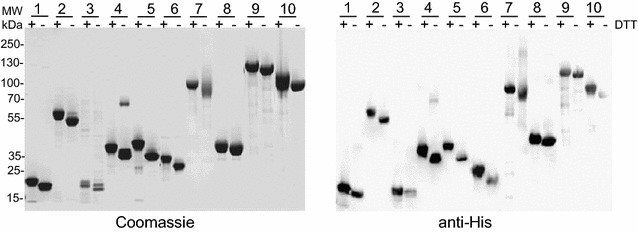

Comparative assessment of purified recombinant merozoite proteins

Most of the purified cysteine-rich recombinant proteins migrated as a single band by SDS-PAGE under non-reducing conditions with apparent molecular weights, which are in agreement with those predicted from the deduced amino acid sequence (Fig. 3). The addition of a reducing agent resulted in a band shift in the mobility of these recombinant proteins on SDS-PAGE demonstrating that these recombinant proteins consist of disulfide-bonds. Disulfide-bonding in these protein preparations was further confirmed by demonstrating no or very low levels (< 1%) of free thiol under native condition. SDS-PAGE analysis also showed that many of the non-disulfide bonded proteins and particularly those with high predicted disorder scores migrated with much higher apparent molecular weights than their respective predicted MWs (Additional file 2). As expected, a strong correlation between anomalous migration as observed by SDS-PAGE and disorder score (Additional file 3, r 0.7554) was observed.

Fig. 3.

Characterization of cysteine-rich recombinant proteins purified by heat treatment method. Left panel: Coomassie blue-stained SDS-PAGE analysis of purified recombinant proteins under non-reducing or under reducing (upon treatment with DTT) conditions. Lanes 1: pf12; 2: SERA5; 3: Pf41; 4: MSPDBL1; 5: MSPDBL2; 6: Pf38; 7: EBA140 RII; 8: GAMA; 9: RIPR and 10: SUB2. Right panel: Corresponding Western Blot analysis using anti-His antibody

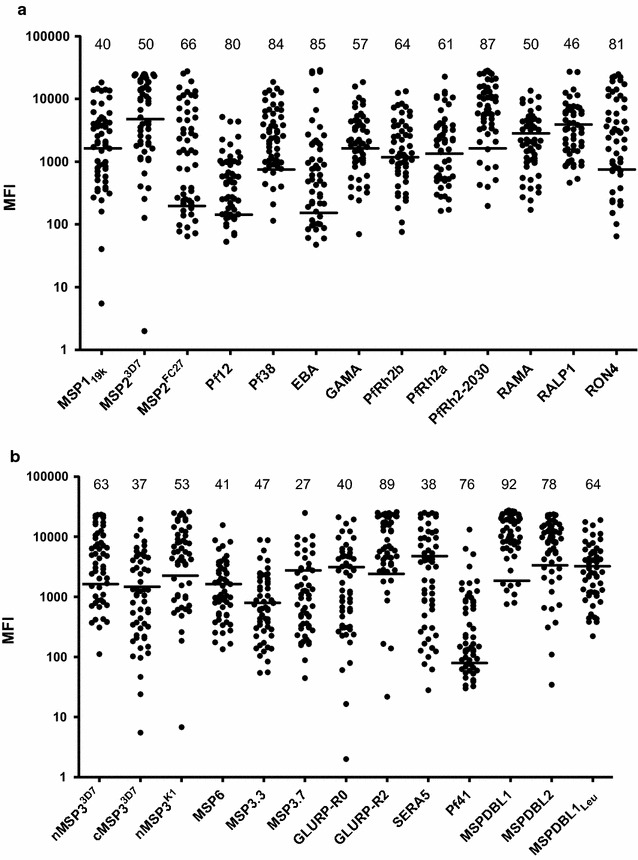

The overall structure of the purified recombinant proteins was also examined by assessing their antigenicity in a multiplex assay (MPA). All antigens were recognized by naturally acquired antibodies in plasma from hyper immune Liberian blood donors (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Antigenic analysis of different target recombinant proteins expressed and purified from L. lactis culture. Total IgG prevalence as observed in 54 malaria hyperimmune Liberian sera against purified recombinant proteins as determined through multiplex analysis. a Antigenic analysis of recombinant proteins derived from membrane anchored P. falciparum antigens which include the GPI-anchored and transmembrane domain containing antigens from secretory organelles (micronemes and rhoptries). b Antigenic analysis of recombinant proteins derived from P. falciparum antigens which are peripherally associated with merozoite surface. The horizontal lines mark the cutoff-levels determined by the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) +2 standard deviations of reactivity of sera from Danish donors who have never been exposed to malaria infection. The numbers listed above scatter plot for each antigen represent the percentage of hyperimmune sera which show positive reactivity against the respective antigen

Discussion

Lactic acid bacteria have a long history of use in the production of fermented foods. More recently, they have also gained importance as microbial cell factories for the production of pharmaceuticals [8, 9]. Development of new vaccines and sero-diagnostic tools constantly pose challenges to the identification of convenient and potent expression systems for recombinant protein production. Here, we have shown that the L. lactis expression systems is ideal for the production of malaria antigens because it (i) accommodates cysteine-rich proteins (ii) offers a scalable fermentation process (iii) allows secretion of the recombinant protein into the culture medium thereby simplifying the purification process, and (iv) exhibits similar codon bias as P. falciparum and therefore does not require codon optimization prior to protein expression.

Plasmodium falciparum merozoite antigens have previously been produced in E. coli [16], wheat germ cell–free expression system [17] and HEK293 cells [18]. Whereas each of these systems proved successful for some antigens, they also present distinct challenges with respect to producing correct post-translational modifications which usually determine the quality and activity of the target recombinant protein. In eukaryotes such as P. falciparum, the oxidizing environment of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) provides a milieu for disulfide bond formation [19]. Eukaryotic expression systems may potentially form the native disulfide bonds. In contrast, prokaryotic organisms lack the sophisticated ER machinery of and show considerable diversity in their mechanisms and capacity for formation of protein disulfide bonds [20]. Amongst prokaryotes, E. coli has long been the first choice for recombinant protein production potentially giving very high yields. However, expression of disulfide-bonded proteins in E. coli remains challenging and use of different E. coli strains have been proposed to overcome some of these difficulties [2]. Though the mechanisms which control the formation of disulfide bonds in L. lactis are uncharacterized, this system has proved an efficient host for the production of disulfide bonded fragments of Pfs48/45 [21–25].

Glycosylation is another common protein post-translational modification likely to affect the antigenic properties of the recombinant protein depending on the host cell system used for its expression [26]. Since, most of the P. falciparum antigens are non-glycosylated, using eukaryotic expression systems which perform host-specific glycosylation, may compromise essential epitopes of these antigens. To avoid glycosylation these eukaryotic systems necessitate mutation of N-linked glycosylation sites, which in turn might alter functionality [27] and possibly antigenicity and immunogenicity of the recombinant protein. In contrast, L. lactis does not perform unwanted glycosylation and has proven useful for the production of a disulfide-bonded malaria protein [21]. In general, we feel that L. lactis has following advantages over E. coli for expression of malaria recombinant proteins: (1) Codon-optimization of the recombinant malaria gene is not required for obtaining successful expression in L. lactis; (2) Recombinant protein is secreted in the L. lactis culture supernatant making the down-stream processing much easier and less-expensive; and (3) There is no lipo-polysaccharide contamination in L. lactis expression.

In the present study, we have produced a panel of merozoite antigens consisting of proteins with and without disulfide bonds. We found an overall success rate of 55% but it was also evident that the success rate for disulfide-bonded proteins was lower than that for cysteine-poor proteins (9% vs. 80%). In general, the production yield of relatively disordered protein fragments was higher than that of ordered protein regions. The exact reason for this is unknown but it may be speculated that higher solubility, increased stability, or a more efficient transportation across the cell membrane may play a role. Though the underlying mechanism is not clear, addition of an intrinsically disordered protein fragment increased the overall yield of these difficult-to-express protein fragments. Eight out of 10 disulfide bonded proteins produced high levels of recombinant protein when fused to the GLURP R0-region.

GLURP belongs to a group of proteins lacking ordered structure [28, 29], known as intrinsically disordered proteins (IDP). These proteins exist without a well-defined folded structure, having a highly biased amino acid composition with no cysteine and aromatic residues, an overall low hydrophobicity level, and an extremely high content of charged residues (Reviewed in [14, 30, 31]). The relatively, low content of hydrophobic amino acid residues may explain the anomalous migration by SDS-PAGE observed in our study. A deficiency in hydrophobic amino acid residues may result in less binding of SDS [32, 33], thereby slowing migration and therefore resulting in an apparent overestimation of the molecular mass of the recombinant protein through SDS-PAGE analysis.

In the present study we argue that these peculiarities of the amino acid sequences of the intrinsically disorder protein domain of the fusion proteins increased the overall protein expression efficiencies by increasing solubility, resistance to aggregation and possibly by facilitating the translocation of otherwise tightly folded proteins across the cell membrane. The lack of a stable globular structure provides IDP with several extraordinary features including the ability to be unharmed by prolonged heat treatment ([31] and references therein). We have for the first time exploited this feature to provide a highly structured protein with the same indifference to heat treatment. This ability of the IDP was first explored by creating a protein fusion with the disulfide-bonded MSPDBL2. Our results clearly demonstrate that GLURP-R0 protects the integrity of the MSPDBL2 domain from boiling. The MSPDBL2 domain purified by heat-treatment and by conventional purified showed similar HPLC and antigenicity profiles. In contrast, more than 80% of the HCP was eliminated by this heat treatment step possibly because of a low content of intrinsically disordered proteins in L. lactis culture supernatants. The applicability of this method was further examined by creating protein fusions between GLURP-R0 and nine other disulfide-rich merozoite antigens. All fusion proteins were heat stable and the resulting disulfide-rich merozoite antigens were strongly recognized by naturally acquired P. falciparum antibodies with levels and prevalence of specific IgG antibodies which were similar to those observed with malaria antigens produced in several other systems [17, 34, 35]. Whether this novel purification strategy might be applied to other disulfide-rich proteins of non-malarial origin remains to be investigated.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that L. lactis is an efficient host for production of P. falciparum antigens. We have specifically expanded the toolbox to include a novel procedure based on fusion with IDP-carrier protein and successful heat-based purification for production of disulfide-rich proteins. The efficiency of this technique suggests that it could replace the capturing step by IMAC thus, simplifying and accelerating the purification of recombinant proteins. This approach could also facilitate production of affinity-tag free functional recombinant proteins at industrial-scale for clinical applications.

Methods

Preparation of constructs

Target DNA sequences from selected P. falciparum genes (Table 1) were amplified by PCR using gene specific primers. For Sera53D7 and MSP2FC27 we used respective synthetic genes (GeneArt® Life Technologies, Germany). All constructs without the GLURP-R0 carrier were cloned into the BglII restriction site of pSS1 [22]. GLURP fusion proteins were constructed by cloning the target gene into the BglII restriction site of pSS2 [22]. The target gene was amplified with a forward primer containing the DNA sequence encoding for a TEV protease cleavage site (ENLYFQG) thereby creating a protein fusion with the TEV site in the fusion junction. All constructs were verified by sequencing and subsequently transformed into Lactococcus lactis MG1363 by electroporation as described [22].

Screening and fermentation

Five-ten colonies from each transformation were grown overnight at 30 °C in 5 ml LAB medium supplemented with 4% glycerol–phosphate, 5% glucose and 5 μg/ml erythromycin. Culture supernatants were clarified by centrifugation at 9000g for 20 min and protein expression levels were assessed in the culture supernatants by ELISA using HRP-conjugated anti-His antibody (MACS, Miltenyi biotech, Germany) and by SDS-PAGE. L. lactis MG1363 harboring expression constructs was grown in a 1 l stirred bioreactors for 15 h at 30 °C [23]. Cells were removed by centrifugation at 9000 rpm for 30 min and the raw culture supernatant was clarified by filtration. Culture-filtrates were either used immediately or stored at − 20 °C.

Purification of proteins expressed without R0-fusion partner

Culture-filtrates were concentrated fivefold and diafiltrated in quick stand system (GE Healthcare, Sweden) against Tris-buffered saline (TBS) pH 8.0 supplemented with 10 mM imidazole. Recombinant protein was captured from the clarified culture supernatant on a 5 ml HisTrap HP column (GE Healthcare, Sweden). Bound protein was eluted with TBS plus 500 mM imidazole at a flow rate of 4 ml/min and fractions containing the desired protein were pooled and diluted tenfold in 50 mM Tris buffer before loading on the 5 ml HiTrap Q HP or the 5 ml HiTrap SP HP columns (GE Healthcare, Sweden). Bound protein was eluted through gradient elution in 50 mM Tris containing 0–1 M NaCl. Fractions containing the recombinant protein were pooled and buffer exchanged against 50 mM Tris, 300 mM NaCl and 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0.

Purification of recombinant proteins expressed with R0-fusion partner

Recombinant fusion proteins were expressed and affinity purified as described above. The purified fusion protein was digested for 16 h at room temperature with the TEV protease [36], diluted tenfold with 50 mM Tris buffer and loaded on to the ion-exchange chromatography column (Table 1). Bound protein was eluted gradient elution in 50 mM Tris containing 0–1 M NaCl thereby separating the target protein from the GLURP fusion partner and the TEV protease. Purified recombinant protein was concentrated by a VIVA spin column 10 kDa cutoffs (Sartorius, UK), and stored in TBS plus 1 mM EDTA at − 80 °C until use. Protein concentration was determined by the BCA protein assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Purity of target recombinant proteins were monitored using 4–12% Tris-tricine SDS-PAGE gels. Western blotting was performed using HRP-conjugated anti-His and anti-GLURP-R0 antibodies.

Protein purification by boiling

Clarified culture-filtrates were concentrated fivefold and incubated in a boiling water-bath for 10 min followed by immediate cooling in an ice-bath. Host cell proteins (HCP) were removed by centrifugation at 30,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C and the supernatant containing the GLURP-R0 fusion protein was buffer exchanged against TBS and incubated with the TEV protease for 16 h at room temperature and the target protein was purified as described above.

SE-HPLC and free thiol determination

Analytical size exclusion high-performance liquid chromatography (SE-HPLC) of purified proteins was performed using an Agilent 1100 Series HPLC System (Agilent Technologies, USA) equipped with a Agilent advance Bio SEC 300 Å, 2.7 μm, 4.6 × 300 mm SEC column, (Agilent Technologies, GB) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, five hundred pmol of protein was loaded on the SEC column and eluted with a 0.350 ml/min flow of elution buffer (phosphate buffer) at room temperature. Standard proteins from Sigma Aldrich were also run using same the conditions mentioned above for sizing of the purified recombinant proteins. The absorbance was measured at 280 nm and chromatographic peaks were integrated by HPLC ChemStation (Agilent Technologies, CA, US). The amount of free cysteine residues was measured using Ellman’s Reagent (Thermo fisher scientific, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. A standard curve was constructed using known concentrations of free cysteine (Sigma-Aldrich, USA).

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and Multiplex analysis

ELISA was performed as described elsewhere [37, 38]. The coating concentration of recombinant protein was 1 μg/ml. Serum samples were used from hyperimmune adults (malaria infected though clinically healthy male blood donors) living in an area in Liberia where malaria is holoendemic, or from Danish donors never exposed to malaria infection [39]. Antigenicity of the purified recombinant proteins was assessed in a multiplex Luminex assay as described elsewhere [40] with minor modifications. Briefly, approximately 1250 microspheres from each of the 26 antigens coupled bead regions were mixed in three separate mixtures. Plex 1 contained: GLURP-R0, GLURP-R2, cMSP33D7, nMSP3K1, MSP3.7, MSP6, Pf38, MSP119k, and BSA; Plex 2 contained, MSPDBL2, SERA5, MSP23D7, Pf41, Pf12, MSP3.3, nMSP33D7 and BSA; and Plex 3 contained MSPDBL1, MSP2FC27, GAMA, RAMA, MSPDBL1Leu, PfRH2-2030, PfRH2a, PfRH2b, RALP-1, RON4, EBA140RIII-V and BSA. EBA140 RII, RIPR, SUB2, RON2 and PfRh4.2 could not be included in the MPA due to either low protein production or unavailability of recombinant proteins during plex preparation. 50 μl of each Plex mixture was added to a 96-well filter micro titer plate (MSBVS 1210, Millipore). For positive and negative controls, a pool of plasma from five hyperimmune Liberian donors and a pool of plasma from eight Danish donors tested at 1:2000 dilutions were used. Fifty-four hyperimmune Liberian and 100 Danish sera samples are tested in singlet at 1:1000 dilution by adding 100 μl/well and incubated with shaking for 2 h in the dark. After three washes, bound IgG was detected with PE-labeled goat anti-human IgG (Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories, West Grove, PA). Levels of specific antibodies against each antigens were nearly identical either determined by the multiplex assay (all beads in each plex) or by single-antigen assay (single bead/antigen), demonstrating that none of the antigens competed for or bound cross-reactive IgG antibodies (data not shown).

Disorder prediction

IUPred software was used for the prediction of protein disorder [41]. For analysis of protein disorder, we estimated a disorder score for each recombinant protein by calculating the percentage of residues with a disorder score above 0.7.

Statistical analysis

The Mann–Whitney rank sum test was used for analyzing differences between groups. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Additional files

Additional file 1. Success rate of obtaining expression of target recombinant protein in L. lactis is not dependent on its biophysical characteristics. Success rate of expression of different target recombinant proteins in L. lactis have been grouped into High, Medium or Low depending on the yield of the respective expression. Yields show poor co-relations with the protein disorder score and presence of cysteine residues (a) and iso-electric point and the predicted molecular weight of the target recombinant proteins (b).

Additional file 2. Successful expression of different P. falciparum antigen derived recombinant proteins in L. lactis. Purity profile of different target recombinant proteins as determined by SDS-PAGE analysis as shown by Coomassie blue staining (top panel) or Western Blot analysis (bottom panel) observed with anti-His antibody.

Additional file 3. Anomalous migration by SDS-PAGE is related to protein disorder. Anomalous mobility was determined as the ratio between the apparent molecular weight as determined by SDS-PAGE and the molecular weight calculated from the deduced amino acid sequence (Table 1). Protein disorder was predicted using the IUPred software [41]. The protein disorder score was estimated by calculating the percentage of residues with a disorder score above 0.7.

Authors’ contributions

SKS, IHK and MT designed the study. SKS, RWT, and BKC collected the data. MT and SS wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Tenna Jensen and Magnus Friis Søndergaard for technical assistance.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets on which the findings and conclusions of this article is based upon are all included in this manuscript and the additional files associated with it.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was funded by the Danish Council for Strategic research (Grants 13127) and the Department of Biotechnology (DBT), Government of India (BT/IN/Denmark/13/SS/2013).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- SEC

analytical size-exclusion chromatography

- ELISA

enzyme linked immunosorbent assay

- IEC

ion exchange chromatography

- IMAC

immobilized metal ion chromatography

- GLURP

glutamate-rich protein of Plasmodium falciparum

- MSP3

merozoite surface protein 3 of Plasmodium falciparum

- MSP119k

merozoite surface protein 1 19 kDa

- MSP23D7

merozoite surface protein 2 3D7 allelic family

- MSP2FC27

merozoite surface protein 2 FC27 allelic family

- Pf12

merozoite surface protein P12

- Pf38

merozoite surface protein P38

- nMSP33D7

merozoite surface protein 3 n-terminal 3D7 allelic family

- cMSP33D7

merozoite surface protein 3 c-terminal 3D7 allelic family

- nMSP3K1

merozoite surface protein 3 n-terminal K1 allelic family

- MSP6

merozoite surface protein 6

- MSP3.3

merozoite surface protein 3.3

- MSP3.7

merozoite surface protein 3.7

- GLURP-R0

glutamate-rich protein R0

- GLURP-R2

glutamate-rich protein R2

- SERA5

Serine Repeat Antigen 5

- Pf41

merozoite surface protein 41

- MSPDBL1

Duffy binding-like merozoite surface protein 1

- MSPDBL2

Duffy binding-like merozoite surface protein 2

- MSPDBL1Leu

Duffy binding-like merozoite surface protein 1 Leucine zipper

- EBA140RIII–V

erythrocyte binding antigen region III–V

- EBA140 RII

erythrocyte binding antigen region III

- GAMA

GPI anchored micronemal antigen

- RIPR

reticulocyte binding protein homologue 5-interacting protein

- SUB2

subtilisin-like protease 2

- PfRh2b

Plasmodium falciparum reticulocyte-binding homolog 2b

- PfRh2a

Plasmodium falciparum reticulocyte-binding homolog 2a

- PfRh4.2

Plasmodium falciparum reticulocyte-binding homolog 4.2

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12934-018-0902-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Susheel K. Singh, Email: susi@sund.ku.dk

Régis Wendpayangde Tiendrebeogo, Email: tregis6@yahoo.fr.

Bishwanath Kumar Chourasia, Email: bnkchourasia@gmail.com.

Ikhlaq Hussain Kana, Email: ikhlaqhssn@gmail.com.

Subhash Singh, Email: subhash@iiim.res.in.

Michael Theisen, Phone: +45 20888302, Email: mth@ssi.dk.

References

- 1.Gaciarz A, Khatri NK, Velez-Suberbie ML, Saaranen MJ, Uchida Y, Keshavarz-Moore E, Ruddock LW. Efficient soluble expression of disulfide bonded proteins in the cytoplasm of Escherichia coli in fed-batch fermentations on chemically defined minimal media. Microb Cell Fact. 2017;16:108. doi: 10.1186/s12934-017-0721-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berkmen M. Production of disulfide-bonded proteins in Escherichia coli. Protein Expr Purif. 2012;82:240–251. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bredmose L, Madsen SM, Vrang A, Ravn P, Johnsen MG, Glenting J, Arnau J, Israelsen H. Development of a heterologous gene expression system for use in Lactococcus lactis. In: Merten O-W, Mattanovich D, Lang C, Larsson G, Neubauer P, Porro D, Postma P, de Teixeira Mattos J, Cole JA, editors. Recombinant protein production with prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2001. pp. 269–275. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Le Loir Y, Azevedo V, Oliveira SC, Freitas DA, Miyoshi A, Bermudez-Humaran LG, Nouaille S, Ribeiro LA, Leclercq S, Gabriel JE, et al. Protein secretion in Lactococcus lactis: an efficient way to increase the overall heterologous protein production. Microb Cell Fact. 2005;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nouaille S, Ribeiro LA, Miyoshi A, Pontes D, Le Loir Y, Oliveira SC, Langella P, Azevedo V. Heterologous protein production and delivery systems for Lactococcus lactis. Genet Mol Res. 2003;2:102–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ravn P, Arnau J, Madsen SM, Vrang A, Israelsen H. Optimization of signal peptide SP310 for heterologous protein production in Lactococcus lactis. Microbiology. 2003;149:2193–2201. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26299-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Theisen M, Soe S, Brunstedt K, Follmann F, Bredmose L, Israelsen H, Madsen SM, Druilhe P. A Plasmodium falciparum GLURP-MSP3 chimeric protein; expression in Lactococcus lactis, immunogenicity and induction of biologically active antibodies. Vaccine. 2004;22:1188–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bahey-El-Din M. Lactococcus lactis-based vaccines from laboratory bench to human use: an overview. Vaccine. 2012;30:685–690. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.11.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Theisen M, Adu B, Mordmuller B, Singh S. The GMZ2 malaria vaccine: from concept to efficacy in humans. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2017;16:907–917. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2017.1355246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller LH, Aikawa M, Dvorak JA. Malaria (Plasmodium knowlesi) merozoites: immunity and the surface coat. J Immunol. 1975;114:1237–1242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cowman AF, Tonkin CJ, Tham WH, Duraisingh MT. The molecular basis of erythrocyte invasion by malaria parasites. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;22:232–245. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boucher LE, Bosch J. The apicomplexan glideosome and adhesins—structures and function. J Struct Biol. 2015;190:93–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beeson JG, Drew DR, Boyle MJ, Feng G, Fowkes FJ, Richards JS. Merozoite surface proteins in red blood cell invasion, immunity and vaccines against malaria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2016;40:343–372. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuw001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tompa P. The interplay between structure and function in intrinsically unstructured proteins. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:3346–3354. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalthoff C. A novel strategy for the purification of recombinantly expressed unstructured protein domains. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2003;786:247–254. doi: 10.1016/S1570-0232(02)00908-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rono J, Osier FH, Olsson D, Montgomery S, Mhoja L, Rooth I, Marsh K, Farnert A. Breadth of anti-merozoite antibody responses is associated with the genetic diversity of asymptomatic Plasmodium falciparum infections and protection against clinical malaria. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:1409–1416. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richards JS, Arumugam TU, Reiling L, Healer J, Hodder AN, Fowkes FJ, Cross N, Langer C, Takeo S, Uboldi AD, et al. Identification and prioritization of merozoite antigens as targets of protective human immunity to Plasmodium falciparum malaria for vaccine and biomarker development. J Immunol. 2013;191:795–809. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crosnier C, Wanaguru M, McDade B, Osier FH, Marsh K, Rayner JC, Wright GJ. A library of functional recombinant cell-surface and secreted P. falciparum merozoite proteins. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12:3976–3986. doi: 10.1074/mcp.O113.028357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bulleid NJ. Disulfide bond formation in the mammalian endoplasmic reticulum. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4:a013219. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a013219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dutton RJ, Boyd D, Berkmen M, Beckwith J. Bacterial species exhibit diversity in their mechanisms and capacity for protein disulfide bond formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:11933–11938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804621105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Theisen M, Roeffen W, Singh SK, Andersen G, Amoah L, van de Vegte-Bolmer M, Arens T, Tiendrebeogo RW, Jones S, Bousema T, et al. A multi-stage malaria vaccine candidate targeting both transmission and asexual parasite life-cycle stages. Vaccine. 2014;32:2623–2630. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh SK, Roeffen W, Andersen G, Bousema T, Christiansen M, Sauerwein R, Theisen M. A Plasmodium falciparum 48/45 single epitope R0.6C subunit protein elicits high levels of transmission blocking antibodies. Vaccine. 2015;33:1981–1986. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh SK, Roeffen W, Mistarz UH, Chourasia BK, Yang F, Rand KD, Sauerwein RW, Theisen M. Construct design, production, and characterization of Plasmodium falciparum 48/45 R0.6C subunit protein produced in Lactococcus lactis as candidate vaccine. Microb Cell Fact. 2017;16:97. doi: 10.1186/s12934-017-0710-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Acquah FK, Obboh EK, Asare K, Boampong JN, Nuvor SV, Singh SK, Theisen M, Williamson KC, Amoah LE. Antibody responses to two new Lactococcus lactis-produced recombinant Pfs48/45 and Pfs230 proteins increase with age in malaria patients living in the Central Region of Ghana. Malar J. 2017;16:306. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-1955-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mistarz UH, Singh SK, Nguyen T, Roeffen W, Yang F, Lissau C, Madsen SM, Vrang A, Tiendrebeogo RW, Kana IH, et al. Expression, purification and characterization of GMZ2′.10C, a complex disulphide-bonded fusion protein vaccine candidate against the asexual and sexual life-stages of the malaria-causing Plasmodium falciparum parasite. Pharm Res. 2017;34:1970–1983. doi: 10.1007/s11095-017-2208-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brooks SA. Protein glycosylation in diverse cell systems: implications for modification and analysis of recombinant proteins. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2006;3:345–359. doi: 10.1586/14789450.3.3.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trulson A, Bystrom J, Engstrom A, Larsson R, Venge P. The functional heterogeneity of eosinophil cationic protein is determined by a gene polymorphism and post-translational modifications. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007;37:208–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Corradin G, Villard V, Kajava AV. Protein structure based strategies for antigen discovery and vaccine development against malaria and other pathogens. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2007;7:259–265. doi: 10.2174/187153007782794371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guy AJ, Irani V, MacRaild CA, Anders RF, Norton RS, Beeson JG, Richards JS, Ramsland PA. Insights into the immunological properties of intrinsically disordered malaria proteins using proteome scale predictions. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0141729. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uversky VN. Paradoxes and wonders of intrinsic disorder: prevalence of exceptionality. Intrinsically Disord Proteins. 2015;3:e1065029. doi: 10.1080/21690707.2015.1065029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uversky VN. Proteins without unique 3D structures: biotechnological applications of intrinsically unstable/disordered proteins. Biotechnol J. 2015;10:356–366. doi: 10.1002/biot.201400374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rath A, Glibowicka M, Nadeau VG, Chen G, Deber CM. Detergent binding explains anomalous SDS-PAGE migration of membrane proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:1760–1765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813167106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nelson CA. The binding of detergents to proteins. I. The maximum amount of dodecyl sulfate bound to proteins and the resistance to binding of several proteins. J Biol Chem. 1971;246:3895–3901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Osier FH, Mackinnon MJ, Crosnier C, Fegan G, Kamuyu G, Wanaguru M, Ogada E, McDade B, Rayner JC, Wright GJ, Marsh K. New antigens for a multicomponent blood-stage malaria vaccine. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:247ra102. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fan YT, Wang Y, Ju C, Zhang T, Xu B, Hu W, Chen JH. Systematic analysis of natural antibody responses to P. falciparum merozoite antigens by protein arrays. J Proteomics. 2013;78:148–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kapust RB, Tozser J, Fox JD, Anderson DE, Cherry S, Copeland TD, Waugh DS. Tobacco etch virus protease: mechanism of autolysis and rational design of stable mutants with wild-type catalytic proficiency. Protein Eng. 2001;14:993–1000. doi: 10.1093/protein/14.12.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dodoo D, Aikins A, Kusi KA, Lamptey H, Remarque E, Milligan P, Bosomprah S, Chilengi R, Osei YD, Akanmori BD, Theisen M. Cohort study of the association of antibody levels to AMA1, MSP119, MSP3 and GLURP with protection from clinical malaria in Ghanaian children. Malar J. 2008;7:142. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nebie I, Diarra A, Ouedraogo A, Soulama I, Bougouma EC, Tiono AB, Konate AT, Chilengi R, Theisen M, Dodoo D, et al. Humoral responses to Plasmodium falciparum blood-stage antigens and association with incidence of clinical malaria in children living in an area of seasonal malaria transmission in Burkina Faso, West Africa. Infect Immun. 2008;76:759–766. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01147-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Theisen M, Vuust J, Gottschau A, Jepsen S, Hogh B. Antigenicity and immunogenicity of recombinant glutamate-rich protein of Plasmodium falciparum expressed in Escherichia coli. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1995;2:30–34. doi: 10.1128/cdli.2.1.30-34.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jepsen MP, Roser D, Christiansen M, Olesen Larsen S, Cavanagh DR, Dhanasarnsombut K, Bygbjerg I, Dodoo D, Remarque EJ, Dziegiel M, et al. Development and evaluation of a multiplex screening assay for Plasmodium falciparum exposure. J Immunol Methods. 2012;384:62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dosztanyi Z, Csizmok V, Tompa P, Simon I. IUPred: web server for the prediction of intrinsically unstructured regions of proteins based on estimated energy content. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3433–3434. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Success rate of obtaining expression of target recombinant protein in L. lactis is not dependent on its biophysical characteristics. Success rate of expression of different target recombinant proteins in L. lactis have been grouped into High, Medium or Low depending on the yield of the respective expression. Yields show poor co-relations with the protein disorder score and presence of cysteine residues (a) and iso-electric point and the predicted molecular weight of the target recombinant proteins (b).

Additional file 2. Successful expression of different P. falciparum antigen derived recombinant proteins in L. lactis. Purity profile of different target recombinant proteins as determined by SDS-PAGE analysis as shown by Coomassie blue staining (top panel) or Western Blot analysis (bottom panel) observed with anti-His antibody.

Additional file 3. Anomalous migration by SDS-PAGE is related to protein disorder. Anomalous mobility was determined as the ratio between the apparent molecular weight as determined by SDS-PAGE and the molecular weight calculated from the deduced amino acid sequence (Table 1). Protein disorder was predicted using the IUPred software [41]. The protein disorder score was estimated by calculating the percentage of residues with a disorder score above 0.7.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets on which the findings and conclusions of this article is based upon are all included in this manuscript and the additional files associated with it.