TO THE EDITOR: Colonic interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC) are recognized as pacemaker cells and are hypothesized to be mediators of canines, innervation.1 In the colon of several species including rodents, canines, and humans, ICC are layered as the sandwich at the level submuscular plexus (ICC-SMP), at the myenteric plexus (ICC-MP), and intramusculature (ICC-IM). These networks of ICC play their different roles in the colon. ICC-SMP and ICC-MP are, in general, responsible for the generation of slow waves that initiate smooth muscle contractions or myogenic contractions; the discrepancy between these 2 networks is that ICC-SMP generate an omnipresent slow wave activity that causes propagating but non-propulsive contractions, whilst ICC-MP generate a stimulus-dependent slow waves as directing propulsive activity.2 ICC-IM, while not responsible in producing slow waves albeit capable of generating unitary potentials,3 is responsible for relaxation of colonic smooth muscles in which ICC are deemed to be a conduit transmitting the signal from nitrergic nerve to the muscle. The alteration or ablation of colonic ICC networks may result in colonic motility function disorder such as constipation.

With great interest, we read the paper by Lee et al4 “comparison of changes in the interstitial cells of Cajal and neuronal nitric oxide synthase-positive neuronal cells with aging between the ascending and descending colon of F344 rats.” Authors compared rat-age at 6, 31, 74 weeks, and 2 years old by screening the expressions of proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase (KIT) and neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) using western blot and immunohistochemistry, and assessing the colonic motility function using bead expulsion and muscle contractility extent.

Notably, the data in the paper reveals some fundamentally essential information upon different regions versus different ages, including quantification of ICC (KIT ratio or percentage), quantification of neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS ratio or percentage) and quantification of neurons (protein gene product [PGP]9.5 percentage and ratio of nNOS/PGP9.5). Such pieces of evidence are bringing a good start to standardize their distributions and normal referrals in rat species. It will be of importance to be criteria in evaluating to what extent of ICC or neuron loss can cause a corresponding motility disorder, and it is indicatable to which approach can validate the relationship of structural injury and malfunction.

Earlier studies provide the evidence that aging decreases the number of ICC bodies and volume at a rate of 13% per decade of life,5 decreases the ganglion cells by 50% to 60% in 24-month-old rats compared with 6-month-old rats,6 and also decreases the expression of nitric oxide synthase and catalytic activity of NOS.7,8 Most studies above are focusing on one or few of factors in account for the relationship of aging and constipation, for example, ICC density is measured using KIT immune staining which is not possible to represent the population from each layer or all of layers of ICC due to technical limitation.

This is the first report in which Lee et al4 combines almost all of metrics including western blotting for KIT, PGP9.5, and nNOS. Then the populations of cells or networks become clear whether or not changed, in addition to segmental and layer analyses. Therefore, this study is practically convincible to illustrate the effect of aging on constipation is not only involved with one type of motility device but also systematically impairment. It suggests elderly constipation possibly caused by not only spontaneous contraction but also stimulus contraction.

However, some concerns are inspired from this publishing for a further discussion:

First, what metrics are applicable for quantifying the density?

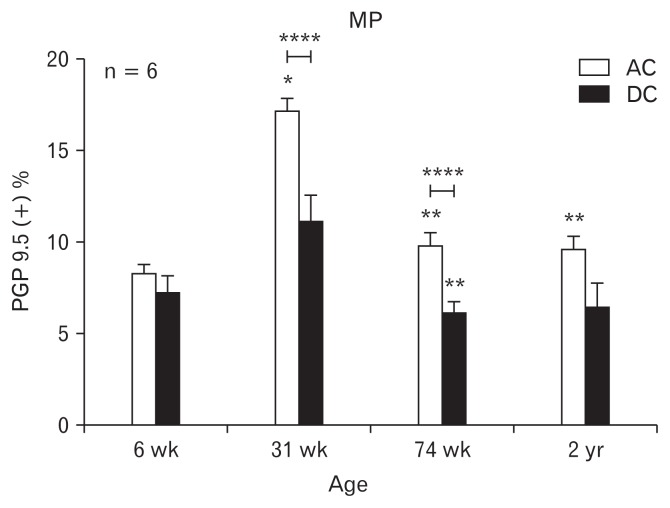

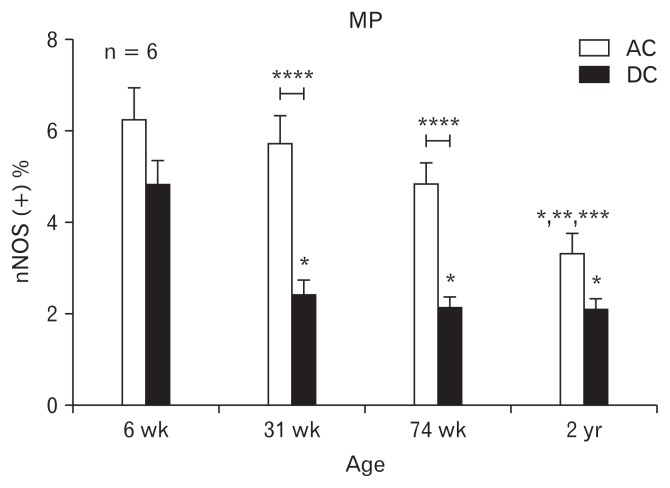

ICC or neurons loss in the gut is a hallmark of several gastrointestinal motility disorders, thus the density of ICC or neuron is widely used as the critical assessment.9–11 As stated by Lee et al4 that the proportion of PGP 9.5 and nNOS immunopositive areas was higher in the ascending colon (AC) than in the descending colon (DC) as shown in Figures 1 and 2 (reproduced from original by Lee et al4), which is explainable on how peristalsis occurs toward to annul direction. But contrarily to the other study performed in humans by Iwase et al,6 it gives an opposite observation that is the area of the ganglion cells was significantly much more in the DC than in the AC (in which the number of ganglia per centimeter averaged 6.9 ± 2.0 in the AC and 8.3 ± 1.6 in the DC). Although the different species and evaluations are not necessarily same, however, the evidence originated conclusion should be consistent. Both studies used immunopositive areas or ganglions in which none defined ganglion cell number or cell size ranges. Thus, as a possible clinical metric to indicate the loss of ICC or neuron will be redefined to be informative or referral in determining gastrointestinal motility disorders.

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical analysis of protein gene product (PGP) 9.5 in the rat colon along with age. The scale represents the proportion of PGP 9.5-immunoreactive area in myenteric plexus (MP). The bars represent the mean ± SEM (each group, n = 6). *P < 0.05 compared to 6-week old rats; **P < 0.05 compared to 31-week old rats; ****P < 0.05 compared to ascending colon. DC, descending colon. Reproduced from original by Lee et al.4

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical analysis of neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) in the rat colon: changes according to age and differences according to colonic region. The proportion of nNOS immunoreactive area in myenteric plexus (MP). The bars represent the mean ± SEM (each group, n = 6). *P < 0.05 compared to 6-week old rats; **P < 0.05 compared to 31-week old rats; ***P < 0.05 compared to 74-week old rats; ****P < 0.05 compared to ascending colon (AC). DC, descending colon. Reproduced from original by Lee et al.4

Second, can structure quantification be relevant as functional change for metric relationship?

Due to different subjects required for different methods, the density of ICC or neurons assessed is different. Several metrics have been found in the literature: cell number, population percentage, network area or volume, level of expression or ratio etc. However, what is the threshold of those that can induce a motility disorder, in other words, how the percentage of cells or networks are being damaged can then cause the functional damage.

Footnotes

Financial support: None

Conflicts of interest: None.

References

- 1.Al-Shboul OA. The importance of interstitial cells of Cajal in the gastrointestinal tract. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:3–15. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.105909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huizinga JD, Martz S, Gil V, Wang X-Y, Jimenez M, Parsons S. Two independent networks of interstitial cells of Cajal work cooperatively with the enteric nervous system to create colonic motor patterns. Front Neurosci. 2011;5:93. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2011.00093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirst GD, Ward SM. Interstitial cells: involvement in rhythmicity and neural control of gut smooth muscle. J Physiol. 2003;550(Pt 2):337–346. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.043299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee SM, Kim N, Jo HJ, et al. Comparison of changes in the interstitial cells of Cajal and neuronal nitric oxide synthase-positive neuronal cells with aging between the ascending and descending colon of F344 rats. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;23:592–605. doi: 10.5056/jnm17061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomez-Pinilla PJ, Gibbons SJ, Sarr MG, et al. Changes in Interstitial Cells of Cajal with Age in the Human Stomach and Colon. Neurogastroenterology and motility : the official journal of the European Gastrointestinal Motility Society. 2011;23:36–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01590.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iwase H, Sadahiro S, Mukoyama S, Makuuchi H, Yasuda M. Morphology of myenteric plexuses in the human large intestine comparison between large intestines with and without colonic diverticula. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:674–678. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000173856.84814.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santer RM, Baker DM. Enteric neuron numbers and sizes in Auerbach’s plexus in the small and large intestine of adult and aged rats. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1988;25:59–67. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(88)90008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takahashi T, Qoubaitary A, Owyang C, Wiley JW. Decreased expression of nitric oxide synthase in the colonic myenteric plexus of aged rats. Brain Res. 2000;883:15–21. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(00)02867-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huizinga JD, Zarate N, Farrugia G. Physiology, injury and recovery of interstitial cells of Cajal: basic and clinical science. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1548–1556. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lyford GL, He CL, Soffer E, et al. Pan-colonic decrease in interstitial cells of Cajal in patients with slow transit constipation. Gut. 2002;51:496–501. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.4.496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kashyap P, Gomez-Pinilla PJ, Pozo MJ, et al. Immunoreactivity for Ano1 detects depletion of Kit-positive interstitial cells of Cajal in patients with slow transit constipation. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:760–765. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01729.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]