Key Points

Question

What is the relative contribution of obesity and psoriasis to comorbidity development in children with psoriasis?

Findings

In this large, retrospective cohort study, both obesity and psoriasis were independent risk factors for comorbidity development in children; the relative contribution from obesity was much higher than that from psoriasis.

Meaning

Children with psoriasis are at risk for comorbidity development independent of obesity status; however, obese children are at significantly higher risk.

Abstract

Importance

Children with psoriasis are at increased risk for comorbidities. Many children with psoriasis are also overweight or obese; it is unknown whether the increased risk of comorbidities in these children is independent of obesity.

Objective

To determine the risk of elevated lipid levels (hyperlipidemia/hypertriglyceridemia), hypertension, metabolic syndrome, polycystic ovarian syndrome, diabetes, nonalcoholic liver disease, and elevated liver enzyme levels in children with and without psoriasis, after accounting for obesity.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This was a retrospective cohort study of claims data from Optum Laboratories Data Warehouse (includes 150 million privately insured and Medicare enrollees). A cohort of 29 957 children with psoriasis (affected children) and an age-, sex-, and race-matched comparator cohort of 29 957 children without psoriasis were identified and divided into 4 groups: (1) nonobese, without psoriasis (reference cohort); (2) nonobese, with psoriasis; (3) obese, without psoriasis; and (4) obese, with psoriasis.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Risk of developing comorbidities (Cox proportional hazards regression).

Results

The overall mean (SD) age of those included in the cohort was 12.0 (4.4) years, and 16 034 (53.5%) were girls. At baseline, more affected children were obese (862 [2.9%] vs 463 [1.5%]; P < .001 for all comparisons). Children with psoriasis were significantly more likely to develop each of the comorbidities than those without psoriasis (P < .01). Obesity was a strong risk factor for development of each comorbidity, even in those without psoriasis (hazard ratios [HRs] ranging from 2.26 to 18.11). The risk of comorbidities was 40% to 75% higher among nonobese children with vs without psoriasis: elevated lipid levels (HR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.25-1.62), hypertension (HR, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.40-1.93), diabetes (HR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.27-1.95), metabolic syndrome (HR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.13-2.33), polycystic ovarian syndrome (HR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.18-1.88), nonalcoholic liver disease (HR, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.16-2.65), and elevated liver enzyme levels (HR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.27-1.67). Except for hypertension (P = .03), no significant interaction occurred between psoriasis and obesity on the risk of comorbidities.

Conclusions and Relevance

Children with psoriasis are at greater risk of developing obesity, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, polycystic ovarian syndrome, nonalcoholic liver disease, and elevated liver function enzyme levels than children without psoriasis. While psoriasis is a small independent risk factor for the development of these comorbidities, obesity is a much stronger contributor to comorbidity development in children with psoriasis.

This cohort study examines the risk ocomorbidities in children with and without psoriasis, after accounting for obesity.

Introduction

Psoriasis is a common inflammatory condition that primarily affects the skin, nails, and joints. Its incidence is rising, including in the pediatric population. Recently, it has been established that adult patients with psoriasis are at risk for comorbidities, such as obesity, cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, depression, and anxiety. In children, the presence of psoriasis is associated with an increased risk of metabolic syndrome and its components and with higher rates of hyperlipidemia, even after controlling for weight, in addition to observed, increased risks of depression and anxiety and a possible increased risk of arthritis and Crohn disease. Most of the evidence for these associations, however, is based on small case series or small population-based studies. Large-scale studies in the United States that evaluate the association of these important comorbidities with psoriasis in childhood are lacking.

Obesity and psoriasis go hand-in-hand in children because children who are obese or overweight are more likely to have psoriasis than those who are of normal weight, and the likelihood and severity of psoriasis increase as weight increases. In childhood, obesity may also be an important risk factor for the development of psoriasis. Because obesity is a known risk factor for psoriasis, as well as for metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease, determining whether psoriasis is an independent risk factor for the development of metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, and other related comorbidities in children would greatly assist in caring for children with psoriasis. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the risk of elevated lipid levels (hyperlipidemia and hypertriglyceridemia), hypertension, metabolic syndrome, polycystic ovarian syndrome, diabetes, nonalcoholic liver disease, and elevated liver enzyme levels in a large population of children with and without psoriasis. We further explored the relative contribution of obesity to the risk of development of these comorbidities in children with and without psoriasis.

Methods

Data Source

We performed a retrospective cohort study using administrative claims data from a large database, Optum Laboratories Data Warehouse, which includes data for more than 150 million privately insured and a number of Medicare Advantage enrollees throughout the United States. The included health plans provide fully insured coverage for inpatient, outpatient, and pharmacy services. Medical claims include diagnosis procedure codes of the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM); Current Procedural Terminology, version 4, procedure codes; Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System procedure codes; and site of service codes and clinician specialty codes. All data were accessed using techniques compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. Because this study involved analysis of preexisting, deidentified data, it was deemed exempt from institutional review board approval.

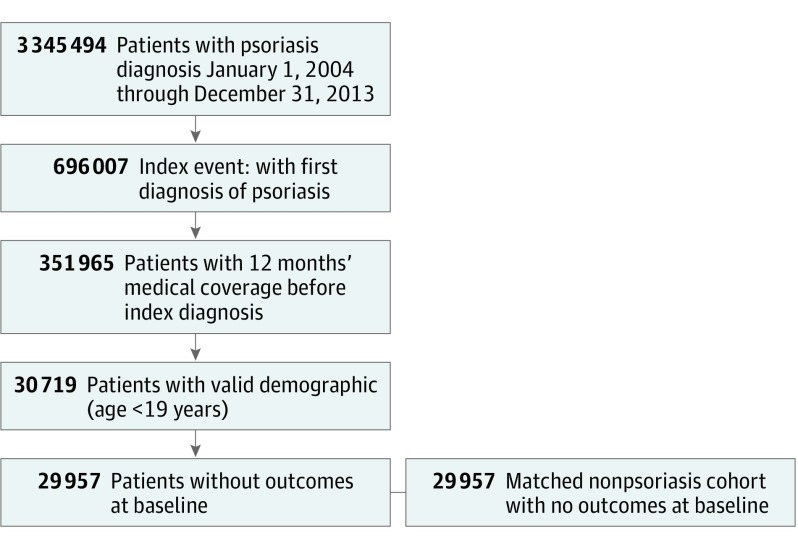

Study Population

We included pediatric patients (age <19 years) diagnosed as having psoriasis over a 10-year period from January 1, 2004, through December 31, 2013. We then identified an age-, sex-, and race-matched comparator group of patients without psoriasis for the same period (Figure 1). The first diagnosis of psoriasis was defined as the incidence date in the psoriasis cohort. The match date was defined as the index date in the cohort without psoriasis. We required patients to have continuous medical enrollment for at least 12 months before the incidence or index date. Patients were followed up until the end of coverage or end of study (December 31, 2015), whichever came first.

Figure 1. Study Population.

Flowchart showing selection of the study population.

Demographic variables included year of birth, sex, and race. Age at incidence/index date was grouped as 1 to 6 years, 7 to 12 years, and 13 to 18 years. Obesity was defined as the presence of an obesity diagnosis within 12 months (±) of the index date.

Outcomes

The outcomes of interest were elevated lipid levels (hyperlipidemia/hypertriglyceridemia), hypertension, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, polycystic ovary disease, nonalcoholic liver disease, and elevated liver enzyme levels. We searched all inpatient and outpatient claims after the index date to the end of coverage or the end of study, whichever came first, for evidence of these conditions using ICD-9 codes in the primary or secondary diagnosis codes (Appendix in the Supplement). Children with these comorbidities within 12 months before the index date were excluded from the analysis.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated frequencies and means for the baseline demographic characteristics. An event rate per 1000 person-years was calculated for each outcome in those with psoriasis and in those without psoriasis. Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was used to obtain hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs for the risk of comorbidities, adjusting for age, sex, race, year of diagnosis, obesity, and psoriasis; and including an obesity-psoriasis interaction. The cohort was divided into 4 groups that were used for comparison: (1) nonobese, without psoriasis (reference cohort); (2) nonobese, with psoriasis; (3) obese, without psoriasis; and (4) obese, with psoriasis. SAS software (version 9.3; SAS Institute Inc) was used for the analyses.

Results

During the 10-year period from 2004 through 2013, 29 957 children with psoriasis and an age-, sex- and race-matched comparator cohort of 29 957 children without psoriasis were identified. A total of 873 patients with psoriasis had a history of 1 or more of the outcomes at baseline and were excluded from the original cohort of 30 719. The overall mean (SD) age of those included in the cohort was 12.0 (4.4) years, and 16 034 (53.5%) were girls. A greater proportion of children with psoriasis had a diagnosis of obesity at baseline (862 [2.9%] vs 463 [1.5%]; P < .001) (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of Children With Psoriasis and Matched Children Without Psoriasis.

| Characteristic | With Psoriasis (n = 29 957) |

Without Psoriasis (n = 29 957) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 12.0 (4.4) | 12.0 (4.4) |

| Age group, No. (%), y | ||

| 1-6 | 4104 (13.7) | 4104 (13.7) |

| 7-12 | 10 485 (35.0) | 10 485 (35.0) |

| 13-18 | 15 368 (51.3) | 15 368 (51.3) |

| Sex, No. (%) | ||

| Female | 16 034 (53.5) | 16 034 (53.5) |

| Male | 13 923 (46.5) | 13 923 (46.5) |

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | ||

| Asian | 873 (2.9) | 873 (2.9) |

| Black | 1418 (4.7) | 1418 (4.7) |

| Hispanic | 1865 (6.2) | 1865 (6.2) |

| White | 16 100 (53.7) | 16 100 (53.7) |

| Unknown | 9701 (32.4) | 9701 (32.4) |

| Obesity, No. (%) | 862 (2.9) | 463 (1.5) |

| Follow-up, y | ||

| Mean (SD) | 3.4 (2.7) | 3.1 (2.6) |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 2.8 (1.2, 5.0) | 2.4 (1.0, 4.4) |

Abbreviation: Q, quartile.

Incidence of Comorbidities Among Children With and Without Psoriasis

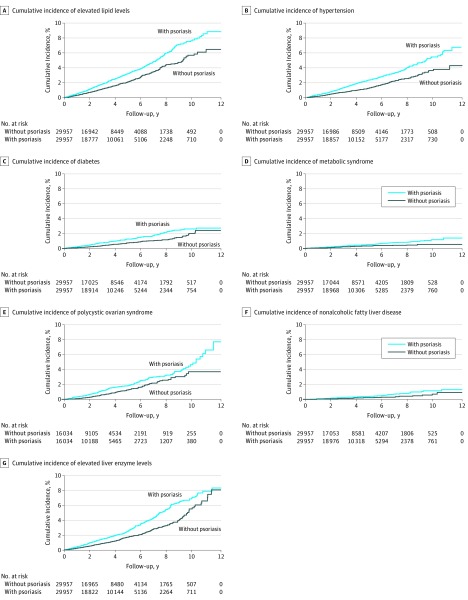

The mean (SD) follow-up of the cohort with psoriasis was 3.4 (2.7) years (median, 2.8 years), and the mean follow-up of the cohort without psoriasis was 3.1 (2.6) years (median, 2.4 years). During follow-up, children with psoriasis were significantly more likely to develop all comorbidities of interest than children without psoriasis; those with the largest HR were nonalcoholic liver disease, diabetes, and hypertension (Table 2). Cumulative incidence for development of each comorbidity is shown in Figure 2.

Table 2. Event Rate per 1000 Person-years and Hazard Ratios (HRs).

| Outcome | Psoriasis | No Psoriasis | HR (95% CI) | P Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Person-years | Event Rate per 1000 | No. | Person-years | Event Rate per 1000 | |||

| Elevated lipid levels | 699 | 101 070.6 | 6.9 | 412 | 90 300.4 | 4.6 | 1.40 (1.24-1.58) | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 499 | 101 729.8 | 4.9 | 261 | 90 733.7 | 2.9 | 1.57 (1.35-1.82) | <.001 |

| Diabetes | 269 | 102 284.4 | 2.6 | 138 | 91 023.2 | 1.5 | 1.63 (1.32-2.00) | <.001 |

| Metabolic syndrome | 115 | 102 705.3 | 1.1 | 57 | 91 236.5 | 0.6 | 1.52 (1.10-2.10) | .01 |

| Polycystic ovarian syndrome | 228 | 54 436.4 | 4.2 | 123 | 48 402.1 | 2.5 | 1.52 (1.22-1.89) | .002 |

| Nonalcoholic liver disease | 97 | 102 762.9 | 0.9 | 43 | 91 272.6 | 0.5 | 1.64 (1.14-2.36) | .008 |

| Elevated liver enzyme levels | 604 | 101 454.1 | 6.0 | 342 | 90 572.7 | 3.7 | 1.49 (1.30-1.70) | <.001 |

Figure 2. Risks for Development of Comorbidities in Children With and Without Psoriasis.

Cumulative incidences demonstrating higher rates for comorbidities in the population of children with psoriasis.

Effect of Psoriasis and Obesity on the Risk of Comorbidities

Obesity was a strong risk factor for all of the comorbidities examined (Table 3). Among unaffected children, obesity was associated with a 6-fold higher risk of hyperlipidemia (HR, 6.16; 95% CI, 4.31-8.81), a 7-fold higher risk of hypertension (HR, 7.27; 95% CI, 4.76-11.09), an almost 3-fold higher risk of diabetes (HR, 2.89; 95% CI, 1.27-6.57), a 16-fold higher risk of metabolic syndrome (HR, 16.18; 95% CI, 8.50-30.81), a 6-fold higher risk of polycystic ovarian syndrome in female children (HR, 5.95; 95% CI, 3.11-11.41), an 18-fold higher risk of nonalcoholic liver disease (HR, 18.11; 95% CI, 8.63-38.03), and a 2.3-fold higher risk of elevated liver enzyme levels (HR, 2.26; 95% CI, 1.24-4.13) than the reference cohort. Psoriasis was also found to be a risk factor for the development of all of the comorbidities examined. Independent of obesity status (ie, among nonobese children), the risk of comorbidities was approximately 40% to 75% higher among children with psoriasis: elevated lipid levels (HR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.25-1.62]), hypertension (HR, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.40-1.93), diabetes (HR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.27-1.95), metabolic syndrome (HR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.13-2.33), polycystic ovarian syndrome (HR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.18-1.88), nonalcoholic liver disease (HR, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.16-2.65), and elevated liver enzyme levels (HR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.27-1.67).

Table 3. Effects of Psoriasis in Obese vs Nonobese Children: Hazard Ratios (95% CIs)a.

| Outcome | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value for Interaction Between Obesity and Psoriasis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| With Psoriasis | Without Psoriasis | ||

| Elevated lipid levels | .12 | ||

| Nonobese | 1.42 (1.25-1.62) | 1 [Reference] | |

| Obese | 6.17 (4.86-7.83) | 6.16 (4.31-8.81) | |

| Hypertension | .03 | ||

| Nonobese | 1.64 (1.40-1.93) | 1 [Reference] | |

| Obese | 6.81 (5.11-9.10) | 7.27 (4.76-11.09) | |

| Diabetes | .34 | ||

| Nonobese | 1.58 (1.27-1.95) | 1 [Reference] | |

| Obese | 7.06 (4.82-10.33) | 2.89 (1.27-6.57) | |

| Metabolic syndrome | .41 | ||

| Nonobese | 1.62 (1.13-2.33) | 1 [Reference] | |

| Obese | 19.03 (12.04-30.08) | 16.18 (8.50-30.81) | |

| Polycystic ovarian syndrome | .74 | ||

| Nonobese | 1.49 (1.18-1.88) | 1 [Reference] | |

| Obese | 10.03 (6.97-14.44) | 5.95 (3.11-11.41) | |

| Nonalcoholic liver disease | .43 | ||

| Nonobese | 1.76 (1.16-2.65) | 1 [Reference] | |

| Obese | 22.54 (13.62-37.30) | 18.11 (8.63-38.03) | |

| Elevated liver enzyme levels | .27 | ||

| Nonobese | 1.46 (1.27-1.67) | 1 [Reference] | |

| Obese | 4.76 (3.59-6.33) | 2.26 (1.24-4.13) | |

Adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, year of diagnosis, Charlson comorbidity index, obesity, and psoriasis; includes an obesity-psoriasis interaction.

We further examined the interaction between obesity and psoriasis on the risk of each of the comorbidities (Table 3). Except for hypertension (P = .03), there was no interaction between psoriasis and obesity. This suggests that even though both obesity and psoriasis are associated with the risk of hypertension, the detrimental effects of obesity on the risk of hypertension are attenuated among children with psoriasis who already have a higher risk of hypertension. Obesity is associated with a 7.27-fold higher risk of hypertension in children without psoriasis but a 4.15-fold higher risk (HRs, 6.81 and 1.64, respectively) in children with psoriasis. A total of 699 patients with psoriasis were diagnosed as having elevated lipid levels after their index date, of which 84 occurred in obese children with psoriasis and 615 occurred in nonobese children with psoriasis. Without any significant interaction terms (P = .12), these findings indicate that both obesity and psoriasis were independent risk factors for the development of hyperlipidemia in children with psoriasis.

Discussion

In recent years, it has become increasingly clear that psoriasis is more than a “skin-deep” condition and that it may frequently be associated with other systemic comorbidities, even in children. While the association in adult patients is well established, the patterns and predictors of the risk of comorbidities in children with psoriasis are still not clear. There is mounting evidence that children with psoriasis are more likely to be obese than children without psoriasis, but this finding begs the question of whether the systemic comorbidities that are seen in children with psoriasis are attributable to obesity, or whether psoriasis is actually an independent risk factor for these comorbidities. We used a large nationwide cohort of children to determine the incidence of comorbidities in affected and unaffected children and to determine the influence of obesity and of psoriasis on those comorbidities.

We identified nearly 30 000 children with psoriasis. The prevalence of psoriasis increased with age as expected, consistent with findings of prior studies. We also found that children with psoriasis had higher rates of obesity, hyperlipidemia and hypertriglyceridemia, hypertension, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, polycystic ovarian syndrome, nonalcoholic liver disease, and elevated liver function test results than closely matched children who did not have psoriasis. Several of these findings are novel, while others had previously been described only in small studies.

In previous large- and small-scale studies in both the United States and other countries, children of all ages with psoriasis were reported to have an increased prevalence of obesity compared with nonaffected controls, which are findings similar to those of our study. Adolescents with psoriasis were reported to have higher rates of hyperlipidemia and hypertriglyceridemia and elevated liver function levels in a retrospective study from an integrated, prepaid health system in the United States, and the hypertriglyceridemia findings have been replicated in smaller-scale prospective studies. To our knowledge, our study is the largest in the United States to describe elevated lipid and triglyceride levels and liver function enzyme levels in children of all ages with psoriasis in the United States. With the large sample size, we had sufficient power to study relatively rare comorbidities, which would otherwise not have been feasible.

Although hypertension and diabetes have been previously identified as possible comorbidities in a German cohort of children with psoriasis and the risk of metabolic syndrome has been described as a comorbidity of adult psoriasis, none of these comorbidities has been well characterized in the US pediatric population. An increased rate of metabolic syndrome was reported in 1 small cohort of 20 children with psoriasis vs controls. We have been able to confirm this increased risk of metabolic syndrome in children with psoriasis on a large scale in the United States. Female polycystic ovarian syndrome and nonalcoholic liver disease are suspected comorbidities in adults with psoriasis, but the description of these risks are novel in the pediatric population.

The discovery of several new comorbidities in pediatric psoriasis is an important one, but it has not yet been determined how much of this risk is attributable to the psoriasis itself. Knowing that these comorbidities are compounded by the presence of obesity, which goes hand-in-hand with psoriasis, we aimed to answer 2 main questions: What are the effects of psoriasis on children who are obese vs those who are not obese, and what are the effects of obesity on children who have psoriasis vs those who do not have psoriasis?

A small study of 20 children with psoriasis and 20 controls showed that children with psoriasis and metabolic syndrome had a higher body mass index (BMI) (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) than those with psoriasis but without metabolic syndrome, suggesting that obesity has a primary role in the development of metabolic syndrome in these children rather than their psoriasis. Whether psoriasis is a risk factor for the development of metabolic syndrome or other comorbidities in the absence of obesity has been, thus far, unknown. In our study, the finding that psoriasis itself increased the risk of developing hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, polycystic ovarian syndrome, nonalcoholic liver disease, and elevated liver enzyme levels in nonobese children with psoriasis is striking. However, the HRs were relatively small in comparison with those for the effects of obesity. This finding suggests that those who care for children must place a greater emphasis on preventing and reducing obesity because it is, overwhelmingly, the more significant factor. However, HRs with psoriasis were consistently increased, suggesting that those who care for children with psoriasis should also maintain a high index of suspicion for comorbidity development, irrespective of BMI percentile or obesity status.

The coexistence of obesity and psoriasis is another important consideration. When psoriasis was added to obesity in regression analyses, trends suggested some increased risk for children developing several comorbidities than when obesity was considered alone (eg, diabetes, polycystic ovarian syndrome, nonalcoholic liver disease, and elevated liver enzyme levels). However, no significant interaction resulted from obesity and psoriasis in our study, suggesting that while obesity and psoriasis both contribute to the development of these comorbidities in children, the effect is additive rather than exponential.

Limitations

There are several potential limitations to this study. First, the data are from administrative claims in a large health care database. Because of this, the diagnoses were not confirmed by medical record review. Undercoding and misclassification of comorbidities are potential limitations. For example, extremely obese patients (eg, BMI > 40) would be more likely to have a corresponding obesity code compared with patients in the BMI range of 25 to 40. The lower prevalence of obesity in our cohort than in some others suggests that obesity may have been undercoded as a whole, with the resulting contribution from psoriasis being slightly overestimated. We also did not have access to complete vital sign measurements or all laboratory values, thus limiting our ability to confirm comorbidity diagnoses. In addition, systemic medications used to treat psoriasis may potentially influence the risk of some of the comorbidities; however, the primary focus of this study was on obesity and psoriasis. Furthermore, owing to the study period, some patients had longer follow-up time than others, although the follow-up time between the cohorts with and without psoriasis was similar. Despite these limitations, this is by far the largest cohort of children with psoriasis studied in the United States, allowing sufficient power to study rare outcomes. Dermatologists and pediatricians have a low rate of screening for comorbidities in pediatric psoriasis; the knowledge gained in this study underscores the importance of closing this practice gap.

Conclusions

Children with psoriasis have higher rates of obesity, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, polycystic ovarian syndrome, nonalcoholic liver disease, and elevated liver function enzyme levels than children who do not have psoriasis. Children with psoriasis are also at increased risk to develop these comorbidities, irrespective of obesity status. However, those children who are obese are much more likely to develop comorbidities than those who are not obese, even in the population of children with psoriasis. Thus, while screening for comorbidities should be considered for all children who have psoriasis, our results highlight the particular importance of screening obese patients because obesity is a much larger contributor to comorbidity development.

eAppendix. Codes Used for Determining Diagnoses and Outcomes

References

- 1.Tollefson MM, Crowson CS, McEvoy MT, Maradit Kremers H. Incidence of psoriasis in children: a population-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62(6):979-987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daudén E, Castañeda S, Suárez C, et al. ; Working Group on Comorbidity in Psoriasis . Clinical practice guideline for an integrated approach to comorbidity in patients with psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27(11):1387-1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lønnberg AS, Skov L, Skytthe A, Kyvik KO, Pedersen OB, Thomsen SF. Association of psoriasis with the risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(7):761-767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Au SC, Goldminz AM, Loo DS, et al. . Association between pediatric psoriasis and the metabolic syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(6):1012-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koebnick C, Black MH, Smith N, et al. . The association of psoriasis and elevated blood lipids in overweight and obese children. J Pediatr. 2011;159(4):577-583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kimball AB, Wu EQ, Guérin A, et al. . Risks of developing psychiatric disorders in pediatric patients with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67(4):651-7.e1, 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Augustin M, Glaeske G, Radtke MA, Christophers E, Reich K, Schäfer I. Epidemiology and comorbidity of psoriasis in children. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162(3):633-636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Augustin M, Radtke MA, Glaeske G, et al. . Epidemiology and comorbidity in children with psoriasis and atopic eczema. Dermatology. 2015;231(1):35-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Najarian DJ, Gottlieb AB. Connections between psoriasis and Crohn’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48(6):805-821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boccardi D, Menni S, La Vecchia C, et al. . Overweight and childhood psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161(2):484-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ozden MG, Tekin NS, Gürer MA, et al. . Environmental risk factors in pediatric psoriasis: a multicenter case-control study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28(3):306-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paller AS, Mercy K, Kwasny MJ, et al. . Association of pediatric psoriasis severity with excess and central adiposity: an international cross-sectional study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(2):166-176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallace PJ, Shah ND, Dennen T, Bleicher PA, Crown WH. Optum Labs: building a novel node in the learning health care system. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(7):1187-1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Optum. Real world health care experiences: Optum research data assets. 2015. https://www.optum.com/content/dam/optum/resources/productSheets/5302_Data_Assets_Chart_Sheet_ISPOR.pdf. Accessed June 2, 2017.

- 15.Bryld LE, Sørensen TI, Andersen KK, Jemec GB, Baker JL. High body mass index in adolescent girls precedes psoriasis hospitalization. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90(5):488-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldminz AM, Buzney CD, Kim N, et al. . Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in children with psoriatic disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30(6):700-705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang C, Zhu KJ, Zheng HF, et al. . The effect of overweight and obesity on psoriasis patients in Chinese Han population: a hospital-based study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(1):87-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu KJ, He SM, Zhang C, Yang S, Zhang XJ. Relationship of the body mass index and childhood psoriasis in a Chinese Han population: a hospital-based study. J Dermatol. 2012;39(2):181-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobi A, Langenbruch A, Purwins S, Augustin M, Radtke MA. Prevalence of obesity in patients with psoriasis: results of the National Study PsoHealth3. Dermatology. 2015;231(3):231-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miele L, Vallone S, Cefalo C, et al. . Prevalence, characteristics and severity of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis. J Hepatol. 2009;51(4):778-786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moro F, Tropea A, Scarinci E, et al. . Psoriasis and polycystic ovary syndrome: a new link in different phenotypes. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2015;191:101-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swary JH, Stratman EJ. Identifying performance gaps in comorbidity and risk factor screening, prevention, and counseling behaviors of providers caring for children with psoriasis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32(6):813-818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Codes Used for Determining Diagnoses and Outcomes