Key Points

Question

In rural US counties, was loss of hospital-based obstetric services associated with changes in location of childbirth or birth outcomes?

Findings

This retrospective cohort study included 4 941 387 births in 1086 rural US counties. Loss of hospital-based obstetric care in rural counties not adjacent to urban areas was significantly associated with increases in births in hospitals without obstetric units (3.06 percentage points), and preterm births (0.67 percentage points), compared with counties with continual obstetric services.

Meaning

In rural US counties not adjacent to urban areas, obstetric services loss was associated with increased risk of birth in hospitals without obstetric units and preterm birth.

Abstract

Importance

Hospital-based obstetric services have decreased in rural US counties, but whether this has been associated with changes in birth location and outcomes is unknown.

Objective

To examine the relationship between loss of hospital-based obstetric services and location of childbirth and birth outcomes in rural counties.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A retrospective cohort study, using county-level regression models in an annual interrupted time series approach. Births occurring from 2004 to 2014 in rural US counties were identified using birth certificates linked to American Hospital Association Annual Surveys. Participants included 4 941 387 births in all 1086 rural counties with hospital-based obstetric services in 2004.

Exposures

Loss of hospital-based obstetric services in the county of maternal residence, stratified by adjacency to urban areas.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Primary outcomes were county rates of (1) out-of-hospital births; (2) births in hospitals without obstetric units; and (3) preterm births (<37 weeks’ gestation).

Results

Between 2004 and 2014, 179 rural counties lost hospital-based obstetric services. Of the 4 941 387 births studied, the mean (SD) maternal age was 26.2 (5.8) years. A mean (SD) of 75.9% (23.2%) of women who gave birth were non-Hispanic white, and 49.7% (15.6%) were college graduates. Rural counties not adjacent to urban areas that lost hospital-based obstetric services had significant increases in out-of-hospital births (0.70 percentage points [95% CI, 0.30 to 1.10]); births in a hospital without an obstetric unit (3.06 percentage points [95% CI, 2.66 to 3.46]); and preterm births (0.67 percentage points [95% CI, 0.02 to 1.33]), in the year after loss of services, compared with those with continual obstetric services. Rural counties adjacent to urban areas that lost hospital-based obstetric services also had significant increases in births in a hospital without obstetric services (1.80 percentage points [95% CI, 1.55 to 2.05]) in the year after loss of services, compared with those with continual obstetric services, and this was followed by a decreasing trend (−0.19 percentage points per year [95% CI, −0.25 to −0.14]).

Conclusions and Relevance

In rural US counties not adjacent to urban areas, loss of hospital-based obstetric services, compared with counties with continual services, was associated with increases in out-of-hospital and preterm births and births in hospitals without obstetric units in the following year; the latter also occurred in urban-adjacent counties. These findings may inform planning and policy regarding rural obstetric services.

This cohort study investigates the association between loss of hospital-based obstetric services between 2004 and 2014 and changes in location of childbirth and preterm births in rural counties in the United States.

Introduction

In 2010, nearly 18 million reproductive-age women lived in rural counties in the United States. The percentage of rural counties with hospital-based obstetric services declined from 55% to 46% between 2004 and 2014, with less-populated rural counties experiencing more rapid declines. Very little is known about whether the loss of rural obstetric services is associated with changes in location of childbirth or outcomes of care. Such information is needed to inform policy and clinical responses to obstetric services loss.

Loss of hospital-based obstetric care may exacerbate existing maternal health challenges in rural communities. Data from 2000 to 2012 showed that women and infants in the most remote rural areas, compared with their urban counterparts, had higher rates of delayed prenatal care initiation, pregnancy-related hospitalizations, low birth weight, preterm births, and infant mortality. Loss of hospital-based obstetric services in rural areas may prolong travel distances and affect access to and outcomes of care during pregnancy and at the time of childbirth. Decreases in care and increases in stress that may accompany loss of nearby obstetric care could influence risk of preterm birth, the leading cause of infant mortality. Hospital obstetric unit closures may also affect location of childbirth. When labor progresses quickly, rural women may give birth at the closest hospital or have an unplanned out-of-hospital birth; others may plan an out-of-hospital birth at or close to home. Successful management of these births requires preparation and readiness on the part of local clinicians and health care systems.

Rural counties vary considerably in their proximity to urban centers, and the consequences of loss of hospital-based obstetric services may differ based on adjacency to an urban area. Distinguishing rural counties based on adjacency to urban areas, this study examined the relationship between losing hospital-based obstetric services and location of childbirth and birth outcomes.

Methods

This study was designated exempt from review by the University of Minnesota institutional review board.

Data and Study Population

Nationwide data came from the 2004-2014 Natality Detail Data maintained by the National Center for Health Statistics. These data included maternal age, race and ethnicity, educational attainment, residence county, pregnancy complications (multiple gestation, diabetes, hypertension, eclampsia, malpresentation, and preterm delivery), gestational age, birth occurrence county, birth weight, parity, and whether the birth occurred in a hospital or not. Race and ethnicity data were self-reported based on fixed categories and were included because maternal and infant outcomes differ by race and ethnicity, as does the racial and ethnic composition of counties.

American Hospital Association Annual Survey data were used to identify all rural counties’ availability of hospital-based obstetric services each year, using a previously documented definition. Specifically, we noted hospitals’ self-reports of (1) provision of obstetric services, (2) level 1 or higher maternity care, (3) at least 1 dedicated obstetric bed, and (4) at least 10 births per year. Hospitals that met all 4 criteria were included. The 56 cases in which there were discrepancies among the 4 indicators were validated against the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ Provider of Services file. Loss of obstetric services included any circumstance whereby all in-county hospital-based obstetric services ceased, including full hospital closures as well as closure of obstetric units in hospitals that remained open. No hospitals reinstated obstetric services during the study period. Rural counties were based on the Federal Office of Management and Budget nonmetropolitan classification, with adjacency to urban areas based on the US Department of Agriculture definition of physically adjoining 1 or more metropolitan counties and having at least 2% of employed residents commuting to metropolitan counties.

Outcomes

Primary and secondary outcomes were identified based on a priori hypotheses formulated from prior literature as well as the strength of available measures of these data. The 3 primary outcomes were (1) out-of-hospital birth, including births in freestanding birth centers or home births that were planned or unplanned; (2) hospital births that occurred in counties that did not have any hospitals that provided obstetric care (eg, births in hospitals without obstetric services); and (3) preterm birth (<37 weeks’ gestation).

Secondary outcomes were (1) low prenatal care use (having ≤10 prenatal visits), (2) cesarean delivery, and (3) low infant Apgar score (<7 at 5 minutes). Secondary outcomes were limited to measures available in birth certificate data throughout the study period. Each has notable limitations, including variation in the quality of prenatal care and in the required number of visits, no consistent assessment of medical necessity of cesarean delivery, and substantial interrater variability in Apgar scores.

Statistical Analysis

Pearson χ2 tests were used to compare differences in maternal and birth characteristics based on whether the counties lost hospital-based obstetric services or had continual services, stratified by adjacency to urban areas.

To assess the relationship between loss of hospital-based obstetric services and study outcomes in urban-adjacent rural counties and non–urban-adjacent rural counties, this study used multivariable linear regression models in an interrupted time series approach, applying the Bonferroni method to control for multiple comparisons (12 comparisons for 6 outcomes in both urban-adjacent and non–urban-adjacent rural counties). This approach measured changes in the level of study outcomes as well as changes in annual trends (slopes) that occurred following loss of hospital-based obstetric services. To do so, we compared outcomes in rural counties that lost hospital-based obstetric services with rural counties that had continual hospital-based obstetric services. The study period comprised 2004 to 2014, and for interrupted time series models, we assessed the association between services loss and outcomes for the counties that lost hospital-based obstetric services between 2006 and 2012, in order to allow at least 2 years prior to and 2 years following closures to assess trends.

Outcomes were assessed for a 1-year period at the county level; thus, we measured annual trends prior to obstetric services loss, changes in the year immediately following closure, and changes in the annual trend that followed closure in counties that experienced services loss compared with those with continual services. Model coefficients produced estimates of the percentage point changes in level or annual trends in study outcomes following services loss. Models were calculated separately for rural counties that were adjacent to urban areas and those that were not adjacent, and statistical differences between rural counties based on adjacency were not assessed. We included all births with complete data on maternal characteristics, maternal clinical conditions, and outcomes. Overall, 109 233 births (2.2%) were missing data on 1 or more measures and were excluded; no one variable had more than 1.6% missing data.

Interrupted time series models adjusted for the following: county-level means of maternal age, race and ethnicity, and educational attainment; maternal clinical conditions (multiple gestation, diabetes, hypertension, eclampsia, and breech); primiparity; and state fixed effects. The model assumed that baseline differences between counties that experienced services loss and those with continual services were accounted for by these measures; unmeasured confounding remains a potential risk. The structure we used assumed that annual trends can be modeled as linear; criteria for this assumption were met. The model also assumed an independent normally distributed residual, which might be violated by autocorrelation: when a county’s outcome in a given year is correlated with the value of that outcome in a prior year. In this analysis, controlling for annual trends reduced the risk of potentially underestimating standard errors.

For all analyses, P < .05 (2-sided) was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using Stata version 13 (StataCorp).

Results

This analysis included 4 941 387 births, occurring between 2004 and 2014, to women who resided in all 1086 rural US counties where hospital-based obstetric services existed in 2004. Across the study population, the mean (SD) maternal age was 26.2 (5.8) years. A mean (SD) of 75.9% (23.2%) of women who gave birth were non-Hispanic white, and 49.7% (15.6%) were college graduates. Table 1 shows descriptive characteristics. During 2004-2014, 179 rural counties lost hospital-based obstetric services, including 103 urban-adjacent rural counties (17.2% of the 599 counties in this category, in which 330 815 births occurred during the study period) and 76 non–urban-adjacent rural counties (15.6% of the 487 counties in this category, in which 112 301 births occurred during the study period). On average, women living in rural counties that lost obstetric services were slightly younger, more likely to be white, and less likely to have a college or graduate degree compared with residents of counties with continual obstetric services.

Table 1. Maternal Characteristics by Hospital Obstetric Services Status (2004-2014) in County of Residence (Non–Urban-Adjacent and Urban-Adjacent Areas).

| Non–Urban-Adjacent Counties | Urban-Adjacent Counties | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continual Hospital Obstetric Services (n = 411 Counties; 1 618 110 Births), % | Loss of Hospital Obstetric Services (n = 76 Counties; 112 301 Births), % | P Value Between Continual Services and Lossa | Continual Hospital Obstetric Services (n = 496 Counties; 2 880 161 Births), % | Loss of Hospital Obstetric Services (n = 103 Counties; 330 815 Births), % | P Value Between Continual Services and Lossa | |

| Maternal age, y | ||||||

| <20 | 12.1 | 12.8 | <.001 | 11.8 | 12.5 | <.001 |

| 20-24 | 31.0 | 32.5 | <.001 | 31.0 | 32.0 | <.001 |

| 25-29 | 29.4 | 29.0 | .02 | 29.3 | 29.4 | .33 |

| 30-34 | 18.4 | 17.3 | <.001 | 18.5 | 17.5 | <.001 |

| ≥35 | 9.2 | 8.3 | <.001 | 9.4 | 8.6 | <.001 |

| Maternal race and ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 70.9 | 77.1 | <.001 | 74.2 | 75.0 | <.001 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 7.6 | 5.2 | <.001 | 9.3 | 11.2 | <.001 |

| Asian | 2.3 | 0.6 | <.001 | 1.1 | 0.7 | <.001 |

| Hispanic | 14.0 | 9.0 | <.001 | 11.9 | 10.4 | <.001 |

| Otherb | 4.4 | 6.9 | <.001 | 3.0 | 2.1 | <.001 |

| Maternal educational attainment | ||||||

| 0-11th grade | 20.1 | 20.3 | <.001 | 20.2 | 20.3 | <.001 |

| High school graduate | 30.8 | 33.9 | <.001 | 33.9 | 30.8 | <.001 |

| College | 43.9 | 41.8 | <.001 | 41.8 | 45.0 | <.001 |

| Graduate degree | 5.3 | 4.0 | <.001 | 4.0 | 3.9 | <.001 |

| Parity | ||||||

| Primipara | 38.0 | 37.1 | <.001 | 38.3 | 37.8 | <.001 |

| Multipara | 61.7 | 62.6 | <.001 | 61.3 | 61.6 | .01 |

| Gestation period, wk | ||||||

| <32 | 2.0 | 2.0 | .68 | 2.1 | 2.2 | <.001 |

| 32-33 | 1.7 | 1.8 | .006 | 1.7 | 1.7 | .02 |

| 34-36 | 9.2 | 9.3 | .21 | 9.0 | 9.3 | <.001 |

| 37-39 | 56.3 | 56.9 | .001 | 56.0 | 56.9 | <.001 |

| 40-41 | 27.4 | 26.4 | <.001 | 27.6 | 26.4 | <.001 |

| ≥42 | 3.5 | 3.7 | <.001 | 3.6 | 3.6 | .20 |

| Maternal clinical conditions | ||||||

| Multiple gestation | 2.9 | 3.0 | .08 | 3.0 | 3.1 | .13 |

| Diabetes | 4.9 | 5.2 | <.001 | 5.0 | 5.0 | .72 |

| Hypertension | 6.5 | 7.0 | <.001 | 6.6 | 6.7 | .07 |

| Eclampsia | 0.3 | 0.3 | .93 | 0.3 | 0.2 | <.001 |

| Breech | 5.1 | 4.8 | <.001 | 5.2 | 4.9 | <.001 |

| Birth weight, g | ||||||

| ≤1499 | 1.3 | 1.3 | .97 | 1.4 | 1.5 | .007 |

| 1500-2499 | 6.8 | 6.8 | .85 | 6.7 | 6.8 | .002 |

| ≥2500 | 91.8 | 91.8 | .84 | 91.8 | 91.6 | .002 |

P values were derived from Pearson χ2 tests for differences in maternal and birth characteristics by maternal residence counties’ hospital obstetric service status.

“Other” maternal race/ethnicity category included Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander, American Indian and Alaska Native, and non-Hispanic of more than 1 race.

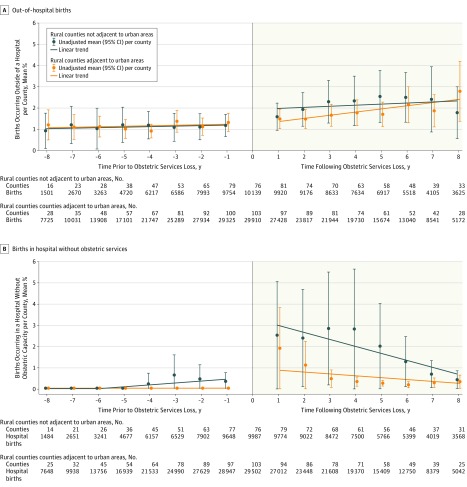

Figure 1 and Figure 2 show observed data trends and 95% CIs in counties that lost hospital-based obstetric services; specific trend slopes before and after services loss, as well as overall trend slopes in counties with continual services, are shown in Table 2 and Table 3. For rural non–urban-adjacent and urban-adjacent counties, the rates of out-of-hospital birth were 1.2% and 1.3%, respectively, in the year preceding obstetric services loss, and the overall trend without loss was increasing by 0.07 and 0.10 percentage points annually, respectively (Figure 1A; Table 2 and Table 3, column 1). For counties that lost hospital-based obstetric services, the observed rate was higher than expected in the absence of services loss. In non–urban-adjacent counties, the rate increased to 1.6% in the year following services loss. For urban-adjacent counties, there was a small increase in out-of-hospital births (to 1.5%) in the year following services loss.

Figure 1. Trends in Birth Location in Rural US Counties That Lost Hospital-Based Obstetric Services in the Years Prior to and Following Services Loss.

The graphs show the trend lines for mean unadjusted values of out-of-hospital births and births in a hospital without obstetric units in rural US counties that lost hospital-based obstetric services as well as 95% CIs in the years prior to and following services loss. The graphs do not include data from rural US counties with continual obstetric services over the study period.

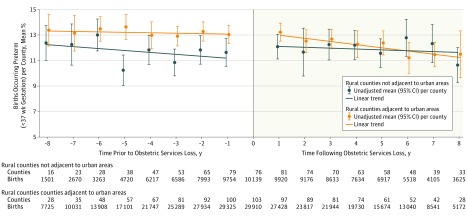

Figure 2. Trend in Preterm Births in Rural US Counties That Lost Hospital-Based Obstetric Services in the Years Prior to and Following Services Loss.

The graph shows the trend lines for mean unadjusted values of preterm births (<37 weeks’ gestation) in rural US counties that lost hospital-based obstetric services as well as 95% CIs in the years prior to and following services loss. The graph does not include data from rural US counties with continual obstetric services over the study period.

Table 2. Estimated Percentage Point Changes in Birth Outcomes Among Rural Counties That Are Not Adjacent to Urban Areas (1 730 411 Births in 487 Counties From 2004 to 2014).

| Descriptive Analysisa | Multivariable Analysisa,b | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Annual Trend in Counties With Continual Services | Annual Trend Before the Loss of Hospital-Based Obstetric Services in Counties With Services Loss | Annual Trend After the Loss of Hospital-Based Obstetric Services in Counties With Services Loss | Changes 1 y After the Loss of Hospital-Based Obstetric Services (vs Counties With Continual Services) | Bonferroni-Corrected P Valuec | Differential Changes in Annual Trend Following Services Loss (vs Counties With Continual Services) | Bonferroni-Corrected P Valuec | |

| Primary Outcomes | |||||||

| Out-of-hospital births |

0.07 (0.04 to 0.10) |

0.09 (−0.01 to 0.19) |

0.11 (−0.01 to 0.22) |

0.70 (0.30 to 1.10) |

<.001 | 0.02 (−0.06 to 0.09) |

>.99 |

| Births in hospital without obstetric unit | 0.01 (−0.01 to 0.03) |

0.10 (0.01 to 0.19) |

0.15 (−0.32 to 0.53) |

3.06 (2.66 to 3.46) |

<.001 | −0.07 (−0.15 to −0.01) |

.08 |

| Preterm births (<37 wk gestation) |

−0.14 (−0.18 to −0.11) |

−0.06 (−0.29 to 0.17) |

−0.19 (−0.34 to −0.04) |

0.67 (0.02 to 1.33) |

.04 | −0.07 (−0.22 to 0.08) |

.16 |

| Secondary Outcomes | |||||||

| ≤10 Prenatal care visits | −0.06 (−0.19 to 0.07) |

0.09 (−0.24 to 0.42) |

0.15 (−0.33 to 0.62) |

4.37 (2.33 to 6.41) |

<.001 | −0.03 (−0.71 to 0.05) |

.90 |

| Cesarean delivery |

−0.16 (−0.26 to −0.07) |

−0.07 (−0.48 to 0.35) |

0.20 (−0.14 to 0.53) |

0.89 (−0.97 to 2.74) |

.43 | 0.10 (−0.24 to 0.46) |

.98 |

| 5-min Apgar score <7 |

0.11 (0.09 to 0.12) |

0.17 (0.05 to 0.29) |

0.15 (0.07 to 0.22) |

0.15 (−0.02 to 0.32) |

.90 | 0.03 (−0.03 to 0.08) |

.36 |

Estimates (95% CIs) were percentage point changes, annually, of each variable from models comparing counties that lost obstetric services with those with continual obstetric services during 2004-2014. A positive change in the year immediately following closure and a positive change in the annual trend that followed services loss refer to the relative increases in outcomes in counties that experienced services loss compared with those with continual services. Bold text indicates corrected P values <.05.

Multivariable models were adjusted for county-level means of maternal age, race and ethnicity (percentage of births to mothers who were non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, Asian, and other; non-Hispanic white was the reference category), educational attainment (percentage of births to mothers whose education levels were 0-11th grades, high school graduate, and college but not a degree; college graduate was the reference category), maternal clinical condition (preterm delivery, multiple gestation, diabetes, hypertension, eclampsia, breech, and primiparity), and maternal residence state fixed effects. Models for Apgar and cesarean delivery measures also controlled for whether there were 10 or fewer prenatal care visits and out-of-hospital births.

P values applied the Bonferroni method to control for multiple comparisons (12 comparisons for 6 outcomes in both urban-adjacent and non–urban-adjacent rural counties).

Table 3. Estimated Percentage Point Changes in Birth Outcomes Among Rural Counties That Are Adjacent to Urban Areas (3 210 976 Births in 599 Counties From 2004 to 2014).

| Descriptive Analysisa | Multivariable Analysisa,b | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Annual Trend in Counties With Continual Services | Annual Trend Before the Loss of Hospital-Based Obstetric Services in Counties With Services Loss | Annual Trend After the Loss of Hospital-Based Obstetric Services in Counties With Services Loss | Changes 1 y After the Loss of Hospital-Based Obstetric Services (vs Counties With Continual Services) | Bonferroni- Corrected P Valuec |

Differential Changes in Annual Trend Following Services Loss (vs Counties With Continual Services) | Bonferroni-Corrected P Valuec | |

| Primary Outcomes | |||||||

| Out-of-hospital births |

0.10 (0.06 to 0.14) |

0.06 (−0.01 to 0.13) |

0.04 (−0.03 to 0.11) |

0.08 (−0.24 to 0.39) |

>.99 | −0.02 (−0.08 to 0.05) |

.31 |

| Births in hospital without obstetric unit | 0.00 (0.00 to 0.00) |

0.00 (−0.01 to 0.00) |

−0.15 (−0.31 to 0.01) |

1.80 (1.55 to 2.05) |

<.001 |

−0.19 (−0.25 to −0.14) |

<.001 |

| Preterm births (<37 wk gestation) |

−0.16 (−0.18 to −0.13) |

−0.06 (−0.24 to 0.12) |

−0.19 (−0.31 to −0.08) |

0.23 (−0.16 to 0.61) |

>.99 |

−0.10 (−0.18 to −0.03) |

.004 |

| Secondary Outcomes | |||||||

| ≤10 Prenatal care visits | −0.04 (−0.15 to 0.07) |

0.03 (−0.41 to 0.47) |

−0.06 (−0.49 to 0.37) |

2.50 (0.71 to 4.03) |

.001 | −0.08 (−0.39 to 0.23) |

.70 |

| Cesarean delivery | −0.09 (−0.18 to −0.01) |

−0.81 (−1.14 to −0.49) |

0.31 (−0.02 to 0.64) |

0.53 (−1.01 to 2.07) |

>.99 | −0.013 (−0.32 to 0.31) |

>.99 |

| 5-min Apgar score <7 |

0.08 (0.07 to 0.10) |

0.07 (0.01 to 0.13) |

−0.06 (−0.12 to −0.01) |

0.03 (−0.33 to 0.39) |

>.99 | −0.03 (−0.10 to 0.04) |

.89 |

Estimates (95% CIs) were percentage point changes, annually, of each variable over all counties from models comparing counties that lost obstetric services to those with continual obstetric services during 2004-2014. A positive change in the year immediately following closure and a positive change in the annual trend that followed services loss refer to the relative increases in outcomes in counties that experienced services loss compared with those with continual services. Bold text indicates corrected P values <.05.

Multivariable models were adjusted for county-level means of maternal age, race and ethnicity (percentage of births to mothers who were non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, Asian, and other; non-Hispanic white was the reference category), educational attainment (percentage of births to mothers whose education levels were 0-11th grades, high school graduate, and college but not a degree; college graduate was the reference category), maternal clinical condition (preterm delivery, multiple gestation, diabetes, hypertension, eclampsia, breech, and primiparity), and maternal residence state fixed effects. Models for Apgar and cesarean delivery measures also controlled for whether there were 10 or fewer prenatal care visits and out-of-hospital births.

P values applied the Bonferroni method to control for multiple comparisons (12 comparisons for 6 outcomes in both urban-adjacent and non–urban-adjacent rural counties).

Births in hospitals without obstetric care were 0.01% in urban-adjacent and 0.40% in non–urban-adjacent counties in the year before services loss; non–urban-adjacent counties had an increasing annual trend of 0.10 percentage points per year prior to services loss (Figure 1B; Table 2, column 2). Following services loss, the rate of births in hospitals without obstetric care was above the trend prior to services loss. Non–urban-adjacent counties had an immediate increase of 2.1 percentage points, from 0.37% to 2.47%. Urban-adjacent counties that lost services had an immediate increase of 1.9 percentage points, from 0.01% to 1.88%.

In the year prior to services loss, preterm birth rates were 11.6% in non–urban-adjacent and 13.0% in urban-adjacent rural counties (Figure 2). The trends in counties with continual obstetric services showed 0.14–percentage point and 0.16–percentage point annual declines over the study period in non–urban-adjacent and urban-adjacent counties, respectively (Table 2 and Table 3, column 1). Raw data showed a 0.40–percentage point increase in preterm birth in the year following services loss in non–urban-adjacent rural counties and a 0.20–percentage point increase in urban-adjacent counties, followed by a 0.19–percentage point average annual decreasing trend in preterm births in both non–urban-adjacent and urban-adjacent counties (Table 2 and Table 3, column 3).

Unadjusted trends in secondary outcomes (low prenatal care use, cesarean delivery, and low Apgar scores) are shown in the eFigure in the Supplement. Non–urban-adjacent counties that lost services had a 46.7% rate of low prenatal care use prior to services loss, and an immediate increase of 2.8 percentage points in low prenatal care use after services loss. Non–urban-adjacent counties had a 31.2% cesarean delivery rate prior to services loss, and an immediate increase of 1.7 percentage points. For non–urban-adjacent counties, low Apgar scores were at 2.17% 1 year prior to services loss and followed an increasing trend of 0.15 percentage points annually after services loss (Table 2, column 3). Urban-adjacent counties that lost hospital-based obstetric services had comparable levels vs non–urban-adjacent counties prior to services loss and saw similar patterns, except that there was a declining trend in cesarean delivery use of 0.81 percentage points per year prior to services loss and a decline in low Apgar scores of 0.06 percentage points per year following services loss (Table 3, columns 2 and 3). Associations between loss of hospital-based obstetric services and study outcomes, controlling for relevant covariates and statistically comparing counties that lost services against those with continual obstetric care, are shown in the multivariable analysis in Table 2 and Table 3. Many observed trends in the raw data did not change in multivariable models, but other patterns (eg, changes in cesarean delivery use and infant Apgar scores) were mitigated when covariates and underlying trends (ie, outcomes in counties with continual services) were accounted for.

The results of multivariable time series models are shown as adjusted marginal changes, presented as percentage points per year, for the associations between services loss and study outcomes in rural counties not adjacent to urban areas and adjacent to urban areas compared with counties with continual obstetric services (Table 2 and Table 3). Table 1 and Table 2 also present unadjusted mean annual trends prior to and following services loss in counties that lost hospital-based obstetric services, as well as overall annual trends in counties with continual services. Among rural counties not adjacent to urban areas, those that lost hospital-based obstetric services experienced significant changes in all 3 primary outcomes and 1 secondary outcome compared with non–urban-adjacent counties with continual obstetric services (Table 2). In the year after loss of services, out-of-hospital births increased (0.70 percentage points [95% CI, 0.30 to 1.10]); births in a hospital without an obstetric unit increased (3.06 percentage points [95% CI, 2.66 to 3.46]) and preterm births increased (0.67 percentage points [95% CI, 0.02 to 1.33]). Low prenatal care (4.37 percentage points [95% CI, 2.33 to 6.41]) also increased (Table 2).

Among rural counties adjacent to urban areas, those that lost hospital-based obstetric services experienced significant changes in 1 primary outcome and 1 secondary outcome compared with urban-adjacent counties with continual obstetric services (Table 3). In the year after loss of hospital-based obstetric services, births in a hospital without obstetric services increased (1.80 percentage points [95% CI, 1.55 to 2.05]), as did low prenatal care use (2.50 percentage points [95% CI, 0.71 to 4.03]). The differences between urban-adjacent counties with services loss and those with continual services in births in a hospital without obstetric services became smaller over time (−0.19 percentage points per year [95% CI, −0.25 to −0.14]), as did rates of preterm birth (−0.10 [95% CI, −0.18 to −0.03]).

Discussion

During the study period, loss of hospital-based obstetric services in rural counties not adjacent to urban areas was associated with an increase in rates of out-of-hospital births, births in a hospital without obstetric services, and preterm births, as well as an increase in low prenatal care use. For rural counties adjacent to urban areas, loss of hospital-based obstetric services was associated with an increase in births in a hospital without obstetric services and low prenatal care use, followed by a decrease over time in the gap between counties with services loss and those with continual services in births in a hospital without obstetric services as well as preterm births.

Altogether, the results of this study indicate significant changes in birth location and outcomes immediately following rural obstetric unit closures, with sustained changes over time in rural counties that are not adjacent to urban areas. Such changes may affect clinical care in an already-challenging context. When a rural hospital stops providing obstetric care or closes entirely, the risks associated with the clinical management of childbirth shift from the hospital to local clinics and staff that may not be equipped to provide obstetric services or to distant communities, with whom rural residents may have little connection.

After losing access to local hospital-based obstetric services, some rural women still gave birth close to home: either at hospitals without obstetric capacity or in out-of-hospital settings, planned or unplanned. The clinical management of care in these situations differs tremendously. In particular, births in hospitals without obstetric capacity and unplanned home births may require substantial unanticipated clinical support from local hospitals, clinics, and emergency medical services. Because this study detected an increase in out-of-hospital births following loss of hospital-based obstetric services in rural non–urban-adjacent counties, particular attention to plans for backup care (should transfer be required) is especially relevant in these communities. Strengthening relationships between home birth clinicians and local hospital-based clinicians following obstetric closures may facilitate collaboration and appropriate transfers of care, when needed.

In most rural counties in this study, birth in a hospital without obstetric services was extremely rare or nonexistent prior to services loss. In rural counties with 100 births a year that lose obstetric services, there may be 2 or 3 births per year that occur in hospitals without obstetric capacity in urban-adjacent and non–urban-adjacent counties, respectively. The health care facilities and clinicians that remain in communities where hospitals close obstetric units may not be equipped to care for patients during labor and delivery, and the clinicians at these facilities do not regularly attend deliveries or identify and manage complications of childbirth. Global data indicate that lacking this care exposes pregnant patients to greater risk of morbidity, mortality, and poor infant outcomes.

Changes in slope in the years following services loss in urban-adjacent counties indicated a reduction over time in births in hospitals without obstetric services, which may suggest a learning curve on the part of patients and delivery systems as they adjust to the loss of hospital-based obstetric care locally. This initial change, followed by a reduced association over time, occurred only in urban-adjacent rural counties. A similar pattern in study outcomes was observed in a 2013 study of obstetric service closures in the Philadelphia metropolitan area. However, in non–urban-adjacent rural counties, the increase in births in hospitals without obstetric units that followed services loss did not decline over time. This difference based on urban adjacency may relate to the distance rural residents must travel to reach a hospital that provides obstetric care.

Loss of hospital-based obstetric services was also associated with an increased risk of preterm birth in non–urban-adjacent rural counties. National Healthy People goals strive for a 10% decline per decade in preterm birth rates. The measured association in this study represents a 5% increase in preterm birth over baseline rates. Preterm birth has lifelong health effects; its predictors are not fully characterized but may include lack of health services as well as psychosocial stress and structural inequities. In the context of obstetric services loss in non–urban-adjacent rural communities, the association with preterm birth may derive in part from reductions in prenatal care, as observed in this study, as well as stress and anxiety experienced by rural residents who lack local access to childbirth services, and particular challenges faced by residents of remote areas.

The percentage of women with low prenatal care use increased in both urban-adjacent and non–urban-adjacent rural counties that lost hospital-based obstetric services, which is consistent with prior studies showing that increased travel time is associated with fewer prenatal care visits. While the clinical consequences of the change are not clear from this or other studies, there is consensus on the need for adequate prenatal care as a means of ongoing assessment, early detection of problems, and creation of a positive pregnancy experience.

Routinely, rural hospital administrators cite staffing needs, financial concerns, and low birth volume as contributing factors to a decision to stop providing obstetric services. These constraints are frequently unavoidable, but new innovative models of organizing and financing care provide opportunities to consider regionalization strategies, partnerships with larger health care systems or tertiary care centers, and the use of telehealth services.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, counties were the only available unit of analysis, but rural counties vary considerably in size and in the spatial distribution of residents. These were factors that could not be accounted for in this analysis. While not currently feasible with national data, future work should assess associations between obstetric services loss and individual outcomes. Second, additional data constraints include the lack of national data during the study period on (1) the intentionality of out-of-hospital births; (2) whether births occurred in emergency departments or whether the birth occurred in a planned location; (3) women’s insurance status and networks, which influence birth setting choices; and (4) timing of prenatal care initiation or use of labor induction, which would have been relevant outcomes to investigate.

Third, the data do not include clinical records, which could contain more details on intended birth location, complications, and outcomes, and the effects on obstetric services loss on individuals could not be determined. Fourth, there were not enough observations within each county to control for correlation among births in counties, and as such, estimates may indicate greater precision than truly exists. Fifth, the analyses were limited to rural counties that had hospital-based obstetric services in 2004 to detect changes after closure. However, this excluded 45% of rural counties where hospital-based obstetric services were not available and where issues of access may be long-standing and exacerbated. Sixth, this was an observational design study, and findings could be explained by residual or unmeasured confounding.

Conclusions

In rural US counties not adjacent to urban areas, loss of hospital-based obstetric services, compared with counties with continual services, was associated with increases in out-of-hospital and preterm births and births in hospitals without obstetric units in the following year; the latter also occurred in urban-adjacent counties. These findings may inform planning and policy regarding rural obstetric services.

eFigure. Trends in Secondary Birth Outcomes in Rural US Counties That Lost Hospital-Based Obstetric Services in the Years Prior to and Following Services Loss

References

- 1.US Census Bureau American Community Survey 5-year estimates: table DP05. American FactFinder website. http://factfinder2.census.gov. Accessed February 24, 2018.

- 2.Hung P, Kozhimannil K, Casey M, Henning-Smith C State variability in access to hospital-based obstetric services in rural US counties. University of Minnesota Rural Health Research Center. http://rhrc.umn.edu/wp-content/files_mf/1491503846UMRHRCOBstatevariability.pdf. Published April 2017. Accessed January 29, 2018.

- 3.Hung P, Henning-Smith CE, Casey MM, Kozhimannil KB. Access to obstetric services in rural counties still declining, with 9 percent losing services, 2004-14. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(9):1663-1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hung P, Kozhimannil K, Henning-Smith C, Casey M Closure of hospital obstetric services disproportionately affects less-populated rural counties. University of Minnesota Rural Health Research Center. http://rhrc.umn.edu/wp-content/files_mf/1491501904UMRHRCOBclosuresPolicyBrief.pdf. Published April 2017. Accessed January 29, 2018.

- 5.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists ACOG committee opinion No. 586: health disparities in rural women. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(2 pt 1):384-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sontheimer D, Halverson LW, Bell L, Ellis M, Bunting PW. Impact of discontinued obstetrical services in rural Missouri: 1990-2002. J Rural Health. 2008;24(1):96-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lisonkova S, Haslam MD, Dahlgren L, Chen I, Synnes AR, Lim KI. Maternal morbidity and perinatal outcomes among women in rural versus urban areas. CMAJ. 2016;188(17-18):E456-E465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rayburn WF, Richards ME, Elwell EC. Drive times to hospitals with perinatal care in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(3):611-616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu L, Oza S, Hogan D, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2000-13, with projections to inform post-2015 priorities: an updated systematic analysis. Lancet. 2015;385(9966):430-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grzybowski S, Stoll K, Kornelsen J. Distance matters: a population based study examining access to maternity services for rural women. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11(1):147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pilkington H, Blondel B, Carayol M, Breart G, Zeitlin J. Impact of maternity unit closures on access to obstetrical care: the French experience between 1998 and 2003. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(10):1521-1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kornelsen J, Stoll K, Grzybowski S. Stress and anxiety associated with lack of access to maternity services for rural parturient women. Aust J Rural Health. 2011;19(1):9-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Callaghan WM, MacDorman MF, Rasmussen SA, Qin C, Lackritz EM. The contribution of preterm birth to infant mortality rates in the United States. Pediatrics. 2006;118(4):1566-1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schorn MN, Wilbeck J. Unexpected birth in the emergency department: the role of the advanced practice nurse. Adv Emerg Nurs J. 2009;31(2):170-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Danilack VA, Nunes AP, Phipps MG. Unexpected complications of low-risk pregnancies in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(6):809.e1-809.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parker T. Urban Influence Codes: documentation. USDA Economic Research Service. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/urban-influence-codes/documentation/. Published May 2013. Accessed February 24, 2018.

- 17.Hutcheon JA, Riddell CA, Strumpf EC, Lee L, Harper S. Safety of labour and delivery following closures of obstetric services in small community hospitals. CMAJ. 2017;189(11):E431-E436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carter EB, Tuuli MG, Caughey AB, Odibo AO, Macones GA, Cahill AG. Number of prenatal visits and pregnancy outcomes in low-risk women. J Perinatol. 2016;36(3):178-181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carter EB, Tuuli MG, Odibo AO, Macones GA, Cahill AG. Prenatal visit utilization and outcomes in pregnant women with type II and gestational diabetes. J Perinatol. 2017;37(2):122-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Donnell CPF, Kamlin COF, Davis PG, Carlin JB, Morley CJ. Interobserver variability of the 5-minute Apgar score. J Pediatr. 2006;149(4):486-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alexander GR, Kotelchuck M. Assessing the role and effectiveness of prenatal care: history, challenges, and directions for future research. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(4):306-316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Partridge S, Balayla J, Holcroft CA, Abenhaim HA. Inadequate prenatal care utilization and risks of infant mortality and poor birth outcome: a retrospective analysis of 28,729,765 U.S. deliveries over 8 years. Am J Perinatol. 2012;29(10):787-793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Committee on Obstetric Practice American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Fetus and Newborn Committee opinion No. 644: the Apgar score. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(4):e52-e55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin JA, Wilson EC, Osterman MJK, Saadi EW, Sutton SR, Hamilton BE. Assessing the quality of medical and health data from the 2003 birth certificate revision: results from two states. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2013;62(2):1-19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Armstrong RA. When to use the Bonferroni correction. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2014;34(5):502-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Penfold RB, Zhang F. Use of interrupted time series analysis in evaluating health care quality improvements. Acad Pediatr. 2013;13(6)(suppl):S38-S44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Declercq E, Macdorman MF, Menacker F, Stotland N. Characteristics of planned and unplanned home births in 19 States. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(1):93-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silver DW, Sabatino F. Precipitous and difficult deliveries. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2012;30(4):961-975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vedam S, Leeman L, Cheyney M, et al. Transfer from planned home birth to hospital: improving interprofessional collaboration. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2014;59(6):624-634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Campbell OMR, Graham WJ; Lancet Maternal Survival Series steering group . Strategies for reducing maternal mortality: getting on with what works. Lancet. 2006;368(9543):1284-1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lorch SA, Srinivas SK, Ahlberg C, Small DS. The impact of obstetric unit closures on maternal and infant pregnancy outcomes. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(2 pt 1):455-475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Department of Health and Human Services Maternal, infant, and child health. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/maternal-infant-and-child-health/objectives. Accessed February 19, 2018.

- 33.Behrman R, Stith Butler A, eds; Institute of Medicine Committee on Understanding Premature Birth and Assuring Healthy Outcones Preterm Birth. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kent ST, McClure LA, Zaitchik BF, Gohlke JM. Area-level risk factors for adverse birth outcomes: trends in urban and rural settings. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13(1):129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McDonald TP, Coburn AF. Predictors of prenatal care utilization. Soc Sci Med. 1988;27(2):167-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.World Health Organization WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/250796/1/9789241549912-eng.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed February 19, 2018. [PubMed]

- 37.Zhao L. Why are fewer hospitals in the delivery business? Bethesda, MD: NORC at the University of Chicago. http://www.norc.org/PDFs/Publications/DecliningAccesstoHospitalbasedObstetricServicesinRuralCounties.pdf. Published April 2007. Accessed February 19, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hung P, Kozhimannil KB, Casey MM, Moscovice IS. Why are obstetric units in rural hospitals closing their doors? Health Serv Res. 2016;51(4):1546-1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lasswell SM, Barfield WD, Rochat RW, Blackmon L. Perinatal regionalization for very low-birth-weight and very preterm infants: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;304(9):992-1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mann S, McKay K, Brown H. The maternal health compact. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(14):1304-1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Trends in Secondary Birth Outcomes in Rural US Counties That Lost Hospital-Based Obstetric Services in the Years Prior to and Following Services Loss