Abstract

This randomized clinical trial compares anticoagulation vs antiplatelet therapy in patients with cancer and acute ischemic stroke.

Patients with cancer face a heightened risk of acute ischemic stroke (AIS). Since many of these strokes are attributed to cancer-mediated hypercoagulability, cancer-associated AIS is often managed with anticoagulation, especially low-molecular weight heparins. However, hypercoagulable stroke mechanisms are rarely definitively diagnosed in patients with cancer antemortem, while atherosclerosis, which is generally managed with antiplatelets, is common in patients with cancer. Furthermore, patients with cancer are predisposed to bleeding, and many randomized clinical trials of anticoagulant therapy have concluded that increased bleeding offsets reductions in stroke risk. Despite these countervailing considerations, to our knowledge, no prospective study has compared antithrombotic strategies in this population.

Methods

We conducted a pilot, open-label, randomized clinical trial comparing enoxaparin with aspirin in patients aged 18 to 85 years with active solid or hematological cancer and magnetic resonance imaging–confirmed AIS within 4 weeks (clinicaltrials.gov NCT01763606) (Supplement). Stroke mechanisms were adjudicated after standardized evaluations. Exclusion criteria are listed in the Figure. Patients were recruited from a comprehensive cancer center and 2 comprehensive stroke centers whose institutional review boards approved this study. Enrolled participants/surrogates provided written consent.

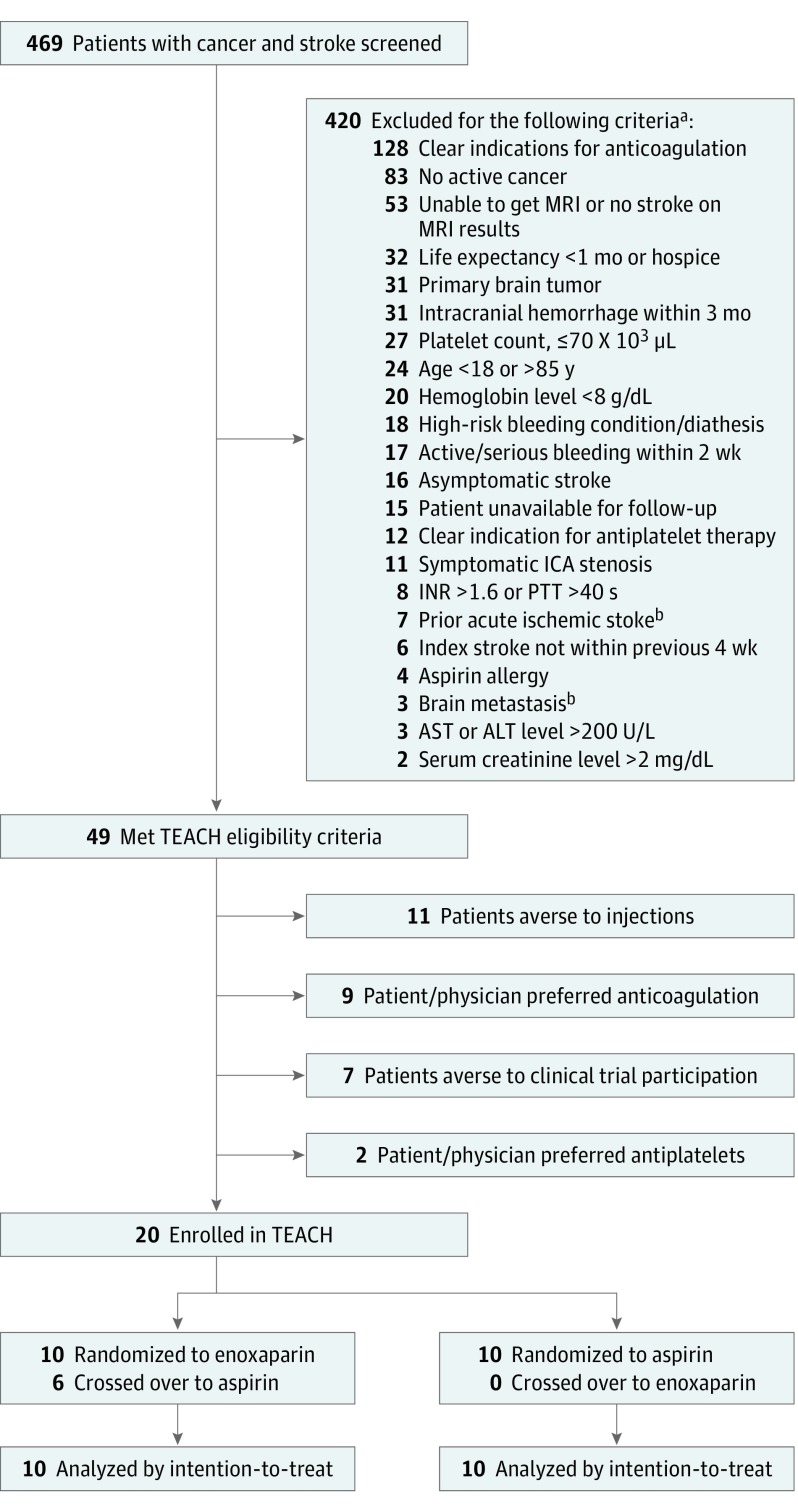

Figure. Study Eligibility Flow Diagram.

Flow diagram detailing patient eligibility, recruitment, randomization, and attrition for the Trial of Enoxaparin vs Aspirin in Patients With Cancer and Stroke (TEACH). SI conversion factors: to convert ALT and AST to microkatals per liter, multiply by 0.0167; creatinine to micromoles per liter, multiply by 88.4; hemoglobin to grams per liter, multiply by 10; platelet count to ×109 microliters, multiply by 1. ALT indicates alanine transferase; AST, aspartate transferase; ICA, internal carotid artery; INR, international normalized ratio; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PTT, partial thromboplastin time.

aSome patients had multiple exclusion criteria.

bExclusion criteria were removed after study initiation to increase patient recruitment.

Patients were randomized electronically to receive subcutaneous enoxaparin (1 mg/kg twice daily) or oral aspirin (81-325 mg/d) for 6 months. Stratified block randomization was performed to ensure similar numbers of adenocarcinomas in each group. Antithrombotic therapy beyond 6 months was determined by treating physicians. Clinical visits occurred at 1, 3, and 6 months, and electronic health records were reviewed until 12 months.

The primary outcome was feasibility, defined as an enrollment rate among 100 eligible patients for which the lower-bound 95% CI exceeded 30%. This was based on the prespecified determination of the investigators that enrolling 40 of 100 eligible participants (40%; 95% CI, 30.3%-50.3%) would indicate feasibility for larger clinical trials. Because of funding constraints, recruitment was halted after 20 enrollments. Descriptive statistics and Kaplan-Meier survival analyses were used to compare feasibility, safety, and efficacy outcomes between intention-to-treat groups.

Results

From January 2013 to April 2016, 469 patients with cancer with suspected AIS were screened; 49 (10.4%) met eligibility criteria. Leading exclusion criteria were clear indications for anticoagulation (n = 128, 30%) and inactive cancer (n = 83, 20%). Investigators enrolled 20 of 49 eligible patients (41%; 95% CI, 27%-55%), indicating that on termination, the study was on pace to meet the prespecified feasibility end point of 30% enrollment. Enrollment failures occurred because of the aversion of patients to receiving injections (n = 11, 38%), patient/physician preferences for anticoagulation (n = 9, 31%), patients declining clinical trial participation (n = 7, 24%), and patient/physician preferences for antiplatelets (n = 2, 7%).

Ten patients were randomized to each arm, and the median (interquartile range) age was 71 (57-76) years (Table). Six patients (60%) who were randomized to receive enoxaparin crossed over to use aspirin during follow-up because of discomfort with receiving injections (n = 4) or drug costs (n = 2). The median time to crossover was 6 days (interquartile range, 1-22).

Table. Baseline Patient Characteristics Stratified by Randomized Treatmenta,b.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Enoxaparin (n = 10) |

Aspirin (n = 10) |

|

| Age, median (IQR), y | 68 (54-75) | 71 (63-81) |

| Female | 8 (80) | 7 (70) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 4 (40) | 8 (80) |

| Black | 4 (40) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 2 (20) | 2 (20) |

| Medical history | ||

| Hypertension | 7 (70) | 8 (80) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 5 (50) | 4 (40) |

| Diabetes | 4 (40) | 2 (20) |

| Coronary heart disease | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Prior stroke | 1 (10) | 2 (20) |

| Current or past tobacco use | 5 (50) | 7 (70) |

| Prior venous thromboembolism | 1 (10) | 1 (10) |

| Cancer type | ||

| Solid tumor | 10 (100) | 9 (90) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 4 (40) | 5 (50) |

| Hematologic | 0 (0) | 1 (10) |

| Cancer features | ||

| Stage, median (IQR) | 4 (4-4) | 4 (3-4) |

| Known systemic metastases | 9 (90) | 9 (90) |

| Prior radiotherapy | 6 (60) | 6 (60) |

| Prior chemotherapy | 9 (90) | 8 (80) |

| Stroke severity | ||

| NIH Stroke Scale, median (IQR) | 2 (0-2) | 2 (0-3) |

| TOAST stroke subtype | ||

| Large artery | 3 (30) | 1 (10) |

| Cardioembolism | 1 (10) | 0 (0) |

| Small vessel | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Other determined | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Undetermined | 6 (60) | 9 (90) |

| Hematologic parameters, median (IQR) | ||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 10.3 (9.9-12.0) | 10.4 (9.8-10.9) |

| Platelet count, ×103/μL | 323 (189-464) | 194 (168-292) |

| D-dimer, μg/mL | 0.329 (0.151-0.524) | 0.682 (0.579-1.899) |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; NIH, National Institutes of Health; TOAST, Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment.

SI conversion factors: to convert D-dimer to nanomoles per liter, multiply by 5.476; hemoglobin to grams per liter, multiply by 10; platelet count to ×109 microliters, multiply by 1.

All data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise specified.

Percentages may not add up to 100 because of rounding.

At 1 year after enrollment, 3 patients who were randomized to receive aspirin had nonfatal gastrointestinal bleeding, while 1 patient who was randomized to receive enoxaparin had nonfatal pulmonary hemorrhage. One patient who was randomized to receive aspirin had nonfatal myocardial infarction, while 1 patient who was randomized to receive enoxaparin had fatal recurrent AIS. The cumulative rates of major bleeding, thromboembolic events, and survival were not significantly different between the groups.

Discussion

In what to our knowledge is the first randomized clinical trial comparing anticoagulation vs antiplatelet therapy in patients with cancer and AIS, approximately 10% of participants were eligible and approximately 40% of these were enrolled, in line with prior stroke clinical trials. The leading reason for enrollment failure was a patient’s aversion to receiving injections, and 40% of patients who were randomized to receive enoxaparin crossed over to using aspirin because of discomfort with receiving injections. Larger blinded clinical trials to determine the optimal antithrombotic strategy for these high-risk patients appear feasible and safe. Comparing aspirin with direct oral anticoagulants instead of injectable heparins should be considered for future clinical trials, assuming the confirmation of preliminary data that suggest that these medicines may be safe and effective for varying manifestations of cancer-associated thrombosis.

Trial Protocol

References

- 1.Navi BB, Reiner AS, Kamel H, et al. . Association between incident cancer and subsequent stroke. Ann Neurol. 2015;77(2):291-300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Navi BB, Singer S, Merkler AE, et al. . Recurrent thromboembolic events after ischemic stroke in patients with cancer. Neurology. 2014;83(1):26-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwarzbach CJ, Schaefer A, Ebert A, et al. . Stroke and cancer: the importance of cancer-associated hypercoagulation as a possible stroke etiology. Stroke. 2012;43(11):3029-3034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Howlett-Smith H, et al. ; Warfarin-Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease Trial Investigators . Comparison of warfarin and aspirin for symptomatic intracranial arterial stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(13):1305-1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elm JJ, Palesch Y, Easton JD, et al. . Screen failure data in clinical trials: Are screening logs worth it? Clin Trials. 2014;11(4):467-472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vedovati MC, Germini F, Agnelli G, Becattini C. Direct oral anticoagulants in patients with VTE and cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2015;147(2):475-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol