This cross-sectional analysis examines the nature of industry payments to physicians who author otolaryngology clinical practice guidelines.

Key Points

Question

What is the extent of potential financial conflicts of interest among physicians who author otolaryngology clinical practice guidelines?

Findings

In this cross-sectional analysis of 49 authors of otolaryngology clinical practice guidelines, 39 received industry payments and 3 did not accurately disclose financial relationships. Of the 3 Institute of Medicine standards assessed, only 1 was being enforced.

Meaning

Guideline authors received significant industry payments, and most panel members received payments from industry, which raises concern about potential financial conflicts of interest in the otolaryngology guideline development process.

Abstract

Importance

Financial relationships between physicians and industry have influence on patient care. Therefore, organizations producing clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) must have policies limiting financial conflicts during guideline development.

Objectives

To evaluate payments received by physician authors of otolaryngology CPGs, compare disclosure statements for accuracy, and investigate the extent to which the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery complied with standards for guideline development from the Institute of Medicine (IOM).

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional analysis retrieved CPGs from the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation that were published or revised from January 1, 2013, through December 31, 2015, by 49 authors. Data were retrieved from December 1 through 31, 2016. Industry payments received by authors were extracted using the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Open Payments database. The values and types of these payments were then evaluated and used to determine whether self-reported disclosure statements were accurate and whether guidelines adhered to applicable IOM standards.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The monetary amounts and types of payments received by physicians who author otolaryngology guidelines and the accuracy of disclosure statements.

Results

Of the 49 physicians in this sample, 39 (80%) received an industry payment. Twenty-one authors (43%) accepted more than $1000; 12 (24%), more than $10 000; 7 (14%), more than $50 000; and 2 (4%), more than $100 000. Mean (SD) financial payments amounted to $18 431 ($53 459) per physician. Total reimbursement for all authors was $995 282. Disclosure statements disagreed with the Open Payments database for 3 authors, amounting to approximately $20 000 among them. Of the 3 IOM standards assessed, only 1 was consistently enforced.

Conclusions and Relevance

Some CPG authors failed to fully disclose all financial conflicts of interest, and most guideline development panels and chairpersons had conflicts. In addition, adherence to IOM standards for guideline development was lacking. This study is relevant to CPG panels authoring recommendations, physicians implementing CPGs to guide patient care, and the organizations establishing policies for guideline development.

Introduction

Relationships between clinicians and the pharmaceutical and device industries are prevalent. One nationwide study published in 2017 examined the extent of these relationships and found that, in 1 year, 48% of physicians accepted $2.4 billion in industry-related payments. Although, in some cases, these relationships may lead to improved patient care, research suggests that they also foster opportunities for significant financial conflicts of interest (FCOIs). For example, physicians who accepted industry payments were twice as likely to prescribe particular brand name drugs, and they may also assess clinical trials more favorably than physicians who did not accept such payments. One study of more than 279 000 physicians across multiple specialties found that industry-sponsored meals, with a mean value of less than $20, were associated with increased rates of prescribing the brand name medication being promoted at significantly higher costs to Medicare beneficiaries. In addition to these issues, FCOIs have the potential to influence development of clinical practice guidelines (CPGs).

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) defines CPGs as “statements that include recommendations intended to optimize patient care that are informed by a systematic review of evidence and an assessment of the benefits and harms of alternative care options”.(p4) Clinical practice guidelines set a standard of patient care. For this reason, ensuring the integrity of the CPG development process is essential. Because of the need for greater transparency, the Physician Payment Sunshine Act was enacted as part of the Affordable Care Act to provide the public with financial information about physician funding from drug and device companies through Open Payments (https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/). Guideline authors are often asked to fully disclose FCOIs; however, evidence suggests that full disclosure is rare. One study examining these disclosure policies found that nearly 50% of CPGs from various specialties cataloged in the National Guideline Clearinghouse did not provide disclosure statements. In addition, nearly half of the CPGs containing disclosures listed authors with industry relationships, and 35% of these authors disclosed an FCOI directly associated with the guideline topic. A similar study investigating professional organizations developing CPGs found that more than half the organizations did not even have an FCOI disclosure policy related to CPGs. The Open Payments database reduces the reliance on authors to self-report FCOIs and supplies the means for an independent evaluation of the extent to which CPG authors have received payments that may compromise CPG development.

Initial research indicates that measures are being taken to reduce FCOIs in otolaryngology; however, the extent of FCOIs pertaining to guideline authors is not as well understood. For example, a 2017 study found that only 2.3% of otolaryngologists as a whole received more than $10 000 in general payments from industry, which is the lowest percentage across all surgical specialties besides obstetrics. Rathi et al found that otolaryngologists received the least amount of nonresearch compensation from industry and had the most restricted ties to industry among all surgical specialties. Another study reported that the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation (AAO-HNS/F) spent $450 000 to develop CPGs, with an individual guideline costing the foundation anywhere from $100 000 to $120 000. This expense is conservative, considering the IOM per guideline estimate of $200 000 to $800 000. Although preliminary evidence suggests less influence of industry on otolaryngology compared with other surgical subspecialties, further research is needed to determine the nature of industry payments received by CPG authors and to better understand whether policies adopted by the AAO-HNS/F are being effectively implemented. This study will explore the value, frequency, and types of payments received by the authors of AAO-HNS/F CPGs to promote transparent development practices among CPG authors. We also compare disclosure forms from CPGs with Open Payments data to evaluate accuracy of CPG author disclosures. Finally, we apply relevant IOM standards for CPG development, to which the AAO-HNS/F subscribes, to the CPG panels to determine the extent to which these standards were enforced by the AAO-HNS/F.

Methods

We performed a cross-sectional analysis to examine the nature of industry payments made to physicians who author otolaryngology CPGs. In developing the methods for this study, we consulted Mitchell et al. This study did not meet the regulatory definition of human subject research as defined in 45 CFR 46.102(d) and (f) of the Department of Health and Human Services and was not subject to institutional review board oversight or the need for informed consent.

One of us (J.X.C.) searched for CPGs from December 1 through 31, 2016, using the AAO-HNS/F website and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s National Guideline Clearinghouse. Inclusion criteria required otolaryngology CPGs to be published or revised from January 1, 2013, through December 31, 2016. Also, the CPG needed a list of contributing physicians who were involved with guideline development. The CPGs produced in the United States were included because only physicians practicing in the United States are subject to the Open Payments provision. We used the time frame of 2013 to 2016 because 2013 was the first year that industry payment data were made available, with 2015 data being the most current. For each guideline, we located dates listed for guideline development. According to the AAO-HNS/F financial and intellectual relationship disclosure policy, panel members are required to disclose all conflicts for the previous 3 years. The AAO-HNS/F’s code for interactions with companies requires authors to remain conflict free for at least 1 year after publication. The IOM also recommends authors avoid FCOIs in the year after publication. The AAO-HNS/F’s code also requires working group members to abstain from speaking about the guideline on behalf of an affected company for 1 year. All collected data fell within this 4-year window recommended by the AAO-HNS/F’s Financial and Intellectual Relationship Disclosure Policy, the CPG code, and the IOM standards. The guideline working group timelines and CPG publication dates are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Dates for CPG Development and Publication.

| CPG Title | Included CPG in Present Study | Guideline Work Group Timeline | Publication Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Otitis Media With Effusion | Yes | Jan to Nov 2015 | Feb 2016 |

| Adult Sinusitis | Yes | Mar 2014 to Jan 2015 | Apr 2015 |

| Tinnitus | Yes | Nov 2012 to Nov 2013 | Oct 2014 |

| Allergic Rhinitis | Yes | Mar 2013 to Mar 2014 | Feb 2015 |

| Acute Otitis Externa | Yes | Oct 2012 to Nov 2013 | Feb 2014 |

| Evaluation of Neck Mass in Adults | No | Aug 2015 to Aug 2016 | Sep 2017 |

| Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo | No | Sep 2015 to Nov 2016 | Mar 2017 |

| Cerumen Impaction | No | Apr 2015 to Jun 2016 | Jan 2017 |

| Improving Nasal Form and Function After Rhinoplasty | No | Apr 2015 to Aug 2016 | Feb 2017 |

| Bell’s Palsy | No | Apr 2012 to Feb 2013 | Nov 2013 |

| Tympanostomy Tubes in Children | No | Sep 2011 to Sep 2012 | Jul 2013 |

| Improving Voice Outcomes after Thyroid Surgery | No | Nov 2011 to Nov 2012 | Jun 2013 |

| Sudden Hearing Loss | No | Jul 2010 to Jul 2011 | Mar 2012 |

| Polysomnography for Sleep-Disordered Breathing Prior to Tonsillectomy in Children | No | Nov 2009 to Sep 2010 | Jul 2011 |

Abbreviation: CPG, clinical practice guideline.

Guideline authors were identified within each CPG. Physicians’ names and affiliations (private or academic) were extracted and copied into an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corp) by one of us (J.X.C.). Names were alphabetized by last name, and duplicates were removed.

One of us (J.X.C.) extracted data by manually entering the physician’s first and last name into the Open Payments search engine. In the event of duplication due to common names, authors were confirmed by using middle initials, company, or location. If the search returned no data or the physician name did not match information provided by Open Payments, the physician was considered to have received no industry payments.

After data extraction, each data element was reviewed for accuracy by another of us (J.H.) by reentering each physician’s first and last names into Open Payments, selecting the correct physician from the search returns, and verifying payment data. Any discrepancies were flagged and resolved jointly between both investigators. We also entered the names of each author into Dollars for Docs, which provides an accounting of the companies who contributed to individual authors.

Open Payment data are classified according to the following subcategories:

General payments include consulting fees, speaking fees, honoraria, gifts, entertainment, food and beverage, travel and lodging, and education.

Research payments include payments associated with a research study, such as basic and applied research and product development.

Associated research payments include funding for a research project or study for which the physician is named as a principal investigator.

Ownership and investment interest in companies describe the actual dollar amount invested and the value of the ownership or investment interest. Records may have 1 or both values associated with them.

Subcategories of reimbursement were classified by year. Means and SDs were calculated by year and by subcategory of reimbursement, and the totals were calculated for each year and subcategory. All calculations were initially performed by one of us (J.X.C.) and independently verified by another of us (J.H.). Excel was used for all calculations.

We used the AAO-HNS/F CPG published disclosure statements for each author to evaluate whether the listed companies were consistent with the companies that reported physician payments. One of us (J.H.) extracted the authors’ names, disclosure date, and FCOI information, which included the company’s name and conflict type (eg, royalties, research, and consultancy). The investigator next searched author’s name in the Open Payments database and recorded payment information. Payment dates were compared with the date of the author’s disclosure statement. Only payments received before the disclosure date were included. Food and beverage were not considered to be discrepancies because the AAO-HNS/F CPGs did not include them as an FCOI category.

Last, we evaluated the extent to which the AAO-HNS/F enforced the standards in the IOM’s Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. As of June 22, 2017, the AAO-HNS/F website stated that “AAO-HNS/F CPGs meet all of the IOM standards for developing a trustworthy clinical practice guideline.” Institute of Medicine standards 1 (establishing transparency) and 2 (management of conflict of interest), in particular 2.1 and 2.4, were relevant to this investigation. Standard 1.1 states, “the processes by which a CPG is developed and funded should be detailed explicitly and publicly accessible.” Standard 2 is composed of 4 parts, but only 2 are evaluable. Standard 2.1 requires written disclosure of all current and planned interests and activities potentially resulting in an FCOI. Standard 2.4 requires members with an FCOI to be a minority of the guideline group and prohibits chairpersons or assistant chairpersons from having FCOIs. We used Open Payments (using the methods described above), the list of authors, and disclosure statements to evaluate whether these standards were enforced.

Results

Five CPGs produced by the AAO-HNS/F met inclusion criteria, and 49 CPG authors were included in the final sample, some of whom served on multiple guidelines. Thirty-four authors were from academic institutions, and 15 were in private practice. All CPGs had a greater proportion of authors from academic institutions, including CPGs titled Otitis Media With Effusion (6 of 11 [55%]), Allergic Rhinitis (9 of 16 [56%]), Tinnitus (13 of 16 [81%]), Adult Sinusitis (6 of 9 [67%]), and Acute Otitis Externa (4 of 7 [57%]). Of these, 39 (80%) received at least 1 reported industry payment. Twenty-one CPG authors (43%) accepted more than $1000; 12 (24%), more than $10 000; 7 (14%), more than $50 000; and 2 (4%), more than $100 000. Jointly, the authors received a mean (SD) of $18 431.15 ($53 459) per author. After removing outliers, the adjusted mean for the sample was $7594. The median total of received industry payments was $227 (range, $0-$55 467.18). Total payment disbursed to the 49 physicians from 2013 to 2015 was $995 282.23. On each CPG panel, most authors received payment from industry, including panels for Allergic Rhinitis (14 of 16 [88%]), Otitis Media With Effusion (8 of 11 [73%]), Adult Sinusitis (6 of 9 [67%]), Acute Otitis Externa (4 of 7 [57%]), and Tinnitus (9 of 16 [56%]). Each CPG panel except that for Tinnitus contained at least 1 author accepting $10 000 or more from industry. Among these CPG panels containing authors accepting $10 000 or more, Allergic Rhinitis had 5 (31%), Adult Sinusitis had 3 (33%), Acute Otitis Externa had 1 (14%), and Otitis Media With Effusion had 1 (9%). Table 2 lists CPG author payments by CPG title.

Table 2. Physician Payments by CPG Title.

| CPG Title (Total No. of Authors per CPG) | No. (%) of Authors | Dates for Which Monetary Data Were Included | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Receiving Payment | Receiving ≥$1000 | Receiving ≥$10 000 | ||

| Tinnitus (n = 16) | 9 (56) | 1 (6) | 0 | Jan 2013 to Dec 2015 |

| Allergic Rhinitis (n = 16) | 14 (88) | 8 (50) | 5 (31) | Jan 2013 to Dec 2015 |

| Otitis Media With Effusion (n = 11) | 8 (73) | 4 (36) | 1 (9) | Jan 2013 to Dec 2015 |

| Adult Sinusitis (n = 9) | 6 (66) | 4 (44) | 3 (33) | Jan 2013 to Dec 2015 |

| Acute Otitis Externa (n = 7) | 3 (43) | 1 (14) | 1 (14) | Jan 2013 to Dec 2015 |

Abbreviation: CPG, clinical practice guideline.

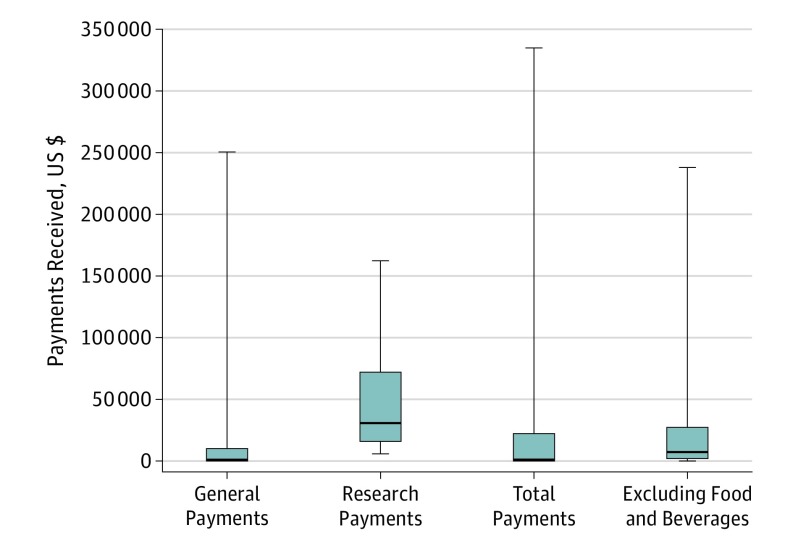

Figure 1 displays all payment data by category. For general payments, CPG authors who accepted payments received a mean (SD) of $11 910 ($43 024), with a median of $223 (interquartile range, $0-$3125.05). Thirty-six CPG authors (73%) received general payments totaling $643 182.50. Seven CPG authors (14%) received research payments, with a mean (SD) of $50 282 ($55 403) and a total of $351 975. No CPG authors had reported ownership interests.

Figure 1. Payments Received by American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation Clinical Practice Guideline (CPG) Authors.

Data are stratified by payment type. Medians are indicated by the horizontal lines within the boxes; interquartile ranges, box limits; and ranges, error bars.

We also ran a subanalysis for the general payments category, excluding authors who received only food and beverage payments. Furthermore, food and beverage payments were excluded in our analysis for authors receiving multiple types of payments (eg, honoraria, consulting fees, and speaking fees). After exclusions, 22 authors were included in the subanalysis, of whom 18 (82%) accepted more than $1000; 7 (32%), more than $10 000; 2 (9%), more than $50 000; and 1 (5%), more than $100 000. Jointly, the authors received a mean (SD) of $21 393 ($48 780). Total payments disbursed was $599 007.32. Figure 1 displays these data.

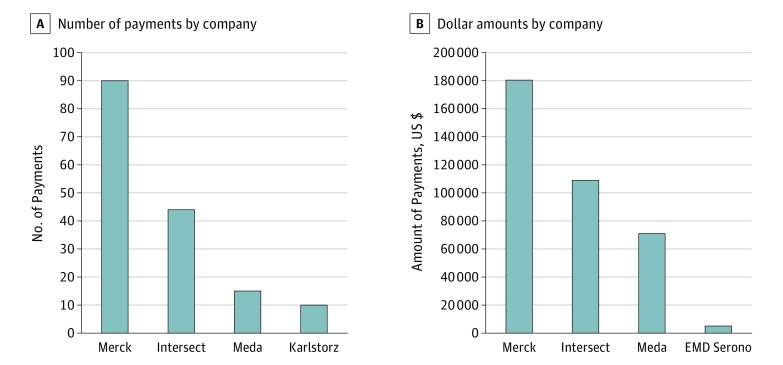

Our analysis using Dollars for Docs found that a few companies contributed most of the payments to the authors, including Merck & Co; Intersect ENT, Inc; Meda Pharmaceuticals, Inc; and Acclarent, Inc. Of the 22 authors with conflicts, 9 (41%) received payments from companies whose products directly relate to the guidelines. Four authors (18%) received payments from Merck & Co totaling $180 437. All these payments were made to physicians authoring the Allergic Rhinitis CPG. This company manufactures several drugs that can be used to treat allergic rhinitis. Intersect ENT, Inc, contributed $108 893 to 3 (14%) authors developing the Allergic Rhinitis CPG. Meda Pharmaceuticals, Inc, which manufactures several nasal sprays that can be used to treat allergic rhinitis, made payments to 3 authors (14%) of the Allergic Rhinitis CPG totaling $74 464. Acclarent, Inc, which manufactures balloon dilation systems used for the treatment of otitis media, contributed $21 700 to authors developing the Otitis Media With Effusion CPG. Figure 2 displays the data for companies contributing payments to the authors of the Allergic Rhinitis CPG. Because the Otitis Media With Effusion and Adult Sinusitis CPGs included had 1 company with relevant contributions and the Tinnitus CPG had none, we did not include them in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Amount of Payments Received by Guideline Authors.

Bar graphs represent data for companies contributing payments to authors of the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation Allergic Rhinitis guideline.

Next, we evaluated the accuracy of self-reported disclosure statements by authors. Of the 49 disclosure statements, 3 (6%) were discrepant when compared with Open Payments data. Undisclosed amounts per authors ranged from approximately $1000 to $13 000.

Finally, we evaluated the extent to which the AAO-HNS/F enforced IOM standards 1, 2.1, and 2.4. The AAO-HNS/F explicitly and publicly disclosed the funding source of each CPG; therefore, the CPGs were in compliance with standard 1. In accordance with standard 2.1, the AAO-HNS/F requires potential authors to disclose FCOIs and explain how FCOIs could affect CPG development; however (as described above), 3 of the 49 authors (6%) did not disclose FCOIs per IOM standard 2.1. Two authors disclosed some FCOIs but did not include every company from which they received payments as reported in Open Payments. One of these authors had nearly $13 000 in undisclosed payments. Another author did not disclose any FCOIs but received significant industry payments totaling $5198.72. The chairperson and most of the assistant chairpersons for each CPG were reported to have received industry payments; therefore, the guideline development group (GDG) for each guideline assessed was not in compliance with IOM standard 2.4. One guideline author and panel member received $3500 in consulting fees and almost $1700 in travel and lodging payments before the date of disclosure; however, the disclosure reported no FCOIs. Another author and panel member on a separate CPG received nearly $1000 for consulting and speaking fees. The other guideline chairpersons and authors accurately reported FCOIs and received no further industry payments during or immediately after guideline development. Seven of 8 chairpersons and assistant chairpersons (88%) received industry payments. Furthermore, another violation of standard 2.4 was found because members with FCOIs represented more than a minority of the GDG.

Discussion

We examined relationships among otolaryngology CPG authors and industry. Our findings demonstrate the following: (1) more than half of each guideline panel received payments from industry; (2) chairpersons had disclosed FCOIs; (3) disclosure statements did not correlate with Open Payments data; and (4) the AAO-HNS/F lacked compliance with IOM standards. Standards not met included members with FCOIs representing more than a minority of the GDG, chairpersons with FCOIs, and authors not properly disclosing financial relationships. Although the amount paid to the otolaryngologists by industry is not significant when compared with amounts paid to other surgical specialties, data suggest that even small payments and gifts can affect physician decision making. For example, although only a few CPG authors received payments of a disproportionately large amount (only 7 authors [14%] accepted more than $50 000), we found that all 5 guidelines assessed had conflicted panel members, ranging from 56% to 88%. This finding is cause for concern, given that on average three quarters of the GDG voting members have FCOIs potentially affecting decision making. This practice is not in compliance with IOM standard 2.4. However, a lack of adherence is not limited to just our findings, because 1 study found that across multiple specialties, none of the evaluated CPGs were in compliance with IOM standards. CPG development needs improvement, and because otolaryngology is among the specialties with the lowest monetary amounts of FCOIs, the field is poised to be a leader in producing CPGs adherent to IOM standards.

We should note that GDGs contained nonphysician voting members, who were not included in the study. We found that most CPG authors were affiliated with academic institutions. Although academics are more likely to be involved in research, their financial relationships with industry are well established. One survey of medical school chairpersons found that almost two-thirds of respondents had ties to industry, with 11% serving on a company board of directors. A similar study from 2015 examined members of the boards of directors for health care companies who were associated with academics (leaders, professors, and trustees). The study showed that of the 442 companies examined, 41% had 1 or more academics as a director. These directors were associated with many prestigious institutions, including 19 of the top 20 National Institutes of Health–funded medical schools and all 17 US News honor roll hospitals. Total annual compensation for these academically associated directors was $54 995 786. The authors concluded that these relationships between industry and nonprofit educational institutions “pose personal, financial, and institutional conflicts of interest beyond that of simple consulting relationships.”(p1)

Several different methods for managing financial conflicts among industry and academia have been posited, including disclosure, institutional review, and prohibition of conflict. Although providing accessible information for the public to examine, conflict disclosure alone is not likely to mitigate competing interests that lead to bias. However, institutional review provides academic centers the ability to prohibit individuals from certain activities and decisions in which their competing interest may introduce bias. Many professional societies recommend this approach. Pisano et al, who include senior academic leaders and an unpaid board member of a health care company, recommend that leaders at academic institutions be prohibited from holding paid positions with health care companies unless the position is outside the scope of the academic role. Regulation and management of financial conflicts is no small task and will most likely be handled on a case-by-case basis.

Our study also found that for every guideline assessed, each CPG had conflicts in leadership in the chairperson, the assistant chairperson, or both. This finding reveals noncompliance with another tenet of IOM standard 2.4 and raises concern about the independence and transparency of these guidelines. Chairpersons are identified to lead the GDG, with responsibilities that include guiding panel discussions, selecting panel members, and delegating writing assignments. If a GDG chairperson has FCOIs, industry influence could begin to take effect before the panel members are selected. For example, 1 study found that for diabetes and hyperlipidemia alone, half of the guidelines assessed had chairpersons with FCOIs. Therefore, the authors concluded that industry has an influence on guideline recommendations. Furthermore, the AAO-HNS/F’s Clinical Practice Guideline Development Manual states that each chair is selected by a panel that includes AAO-HNS/F leadership administration. These findings suggest that the panel selecting the chairpersons did not abide by their own policy or the IOM standards in selecting chairpersons with disclosed FCOIs.

In addition to IOM standards, the AAO-HNS/F explicitly describes their FCOI policy in its Code for Interaction with Companies. One key point of this policy requires disclosing all potential FCOIs of GDG members. We found a total of 3 authors (6%) from different guidelines who had disclosures that were discrepant with Open Payments data. One of these authors failed to disclose any FCOI. Although this practice is not in compliance with IOM standards or the AAO-HNS/F’s own FCOI policy, compared with all other specialties, this rate of nondisclosure is low. For example, Andreatos et al found that FCOI disclosure among panel members is relatively rare (approximately 10%), concluding that this finding “clearly indicates the need for heightened vigilance in the management and public reporting of potential FCOIs.”(p5) The AAO-HNS/F’s disclosure policies and practices could become examples for other organizations developing CPGs.

Recommendations

Our findings suggest the need for improvements in FCOI policies among organizations developing CPGs. Evidence indicates that disclosure alone is not sufficient to mitigate panel member bias from influencing recommendations. Neuman et al suggest that reducing FCOIs of individual panel members will be more effective to mitigate bias than mere disclosure. We suggest enforcement of the AAO-HNS/F’s policy limiting FCOIs to a minority (<50%) of panel members. The AAO-HNS/F might also consider identifying a monetary value that clearly defines what they consider to be an FCOI. For example, the American College of Radiology defines FCOI as “a compensation arrangement (eg, consulting fees, honoraria, and other payments for service) of at least $10 000.00 annually with any entity or individual with which ACR has a transaction or arrangement.”(p2) This definition would set clear standards for guideline authors potentially promoting adherence. Although the AAO-HNS/F requires authors to update disclosure information at least annually and when material changes occur, the mechanism for authors to do so seems to be unclear. Implementing a clear mechanism for authors to update their disclosure after guideline publication is an opportunity for improving the guideline development process regarding transparency. Finally, we recommend that the AAO-HNS/F abide by their own policy as well as the IOM standards when selecting GDG chairpersons. We also recommend the addition of a medical ethicist to the review board who would evaluate the FCOI disclosure forms and could then inform the leadership administration which potential guideline members and chairpersons have relevant FCOIs. Implementing these practices would promote selection of a guideline panel that complies with IOM standards and the AAO-HNS/F’s own policies.

Limitations

Limitations of this study include possible human error or inaccurate data from the Open Payments site. For example, multiple clinicians could have the same name, leading to potential inaccuracies during data extraction. Some physicians were not retrievable during searches, which could mean that the physician did not receive payments or that parties responsible for reporting payments failed to do so. If the latter is the case, data will be misleading because no record of payment exists. In addition, Open Payments allots a 45-day period to dispute payments reported by the site. This process has proved to be inefficient. Fewer than 5% of physicians reviewed their data during the program’s inaugural year; therefore, possible errors were not likely to have been rectified. In addition, Open Payments only reports information from US-based physicians; therefore, the generalizations of this study only pertain to the United States.

Conclusions

Authors of otolaryngology CPGs received payments from industry. Our study found that some CPG authors failed to fully disclose all FCOIs, and most guideline development panels and chairpersons were conflicted. We also found a lack of adherence to IOM standards for guideline development. We suggest changes in panel selection, chairperson selection, and the addition of an ethicist to the review board to promote strict compliance with IOM standards. The guideline development process needs to be rectified to ensure credibility of the guidelines produced.

References

- 1.Tringale KR, Marshall D, Mackey TK, Connor M, Murphy JD, Hattangadi-Gluth JA. Types and distribution of payments from industry to physicians in 2015. JAMA. 2017;317(17):1774-1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirschner NM, Sulmasy LS, Kesselheim AS. Health policy basics: the Physician Payment Sunshine Act and the Open Payments Program. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(7):519-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chatterji AK, Fabrizio KR, Mitchell W, Schulman KA. Physician-industry cooperation in the medical device industry. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(6):1532-1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeJong C, Aguilar T, Tseng C-W, Lin GA, Boscardin WJ, Dudley RA. Pharmaceutical industry-sponsored meals and physician prescribing patterns for Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(8):1114-1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell AP, Basch EM, Dusetzina SB. Financial relationships with industry among National Comprehensive Cancer Network guideline authors. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(12):1628-1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor R, Giles J. Cash interests taint drug advice. Nature. 2005;437(7062):1070-1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blum JA, Freeman K, Dart RC, Cooper RJ. Requirements and definitions in conflict of interest policies of medical journals. JAMA. 2009;302(20):2230-2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Norris SL, Holmer HK, Ogden LA, Burda BU. Conflict of interest in clinical practice guideline development: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e25153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper RJ, Gupta M, Wilkes MS, Hoffman JR. Conflict of interest disclosure policies and practices in peer-reviewed biomedical journals. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(12):1248-1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reames BN, Krell RW, Ponto SN, Wong SL. Critical evaluation of oncology clinical practice guidelines. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(20):2563-2568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jefferson AA, Pearson SD. Conflict of interest in seminal hepatitis C virus and cholesterol management guidelines. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(3):352-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Institute of Medicine, Board on Health Care Services, Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woolf SH, Grol R, Hutchinson A, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Clinical guidelines: potential benefits, limitations, and harms of clinical guidelines. BMJ. 1999;318(7182):527-530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ransohoff DF, Pignone M, Sox HC. How to decide whether a clinical practice guideline is trustworthy. JAMA. 2013;309(2):139-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andreatos N, Zacharioudakis IM, Zervou FN, Muhammed M, Mylonakis E. Discrepancy between financial disclosures of authors of clinical practice guidelines and reports by industry. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(2):e5711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.United States Government Publishing Office The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Public law 111–148. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-111publ148/pdf/PLAW-111publ148.pdf. March 23, 2010. Accessed November 11, 2017.

- 17.Norris SL, Holmer HK, Burda BU, Ogden LA, Fu R. Conflict of interest policies for organizations producing a large number of clinical practice guidelines. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e37413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun GH. Conflict of interest reporting in otolaryngology clinical practice guidelines. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;149(2):187-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rathi VK, Samuel AM, Mehra S. Industry ties in otolaryngology: initial insights from the Physician Payment Sunshine Act. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;152(6):993-999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.US Department of Health and Human Services Basic HHS Policy for Protection of Human Research Subjects. Title 45 Code of Federal Regulations part 46. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/regulations/45-cfr- 46/. Accessed December 19, 2016.

- 21.American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. Clinical practice guidelines. http://www.entnet.org/content/clinical-practice-guidelines. Updated October 21, 2017. Accessed December 2016.

- 22.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. National Guideline Clearinghouse https://www.guideline.gov/. Updated October 19, 2017. Accessed December 2016.

- 23.American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. AAO-HNS/F financial and intellectual relationship disclosure policy. http://www.entnet.org/sites/default/files/Financial%20%26%20Intellectual%20Relationship%20Disclosure%20Policy_0.pdf. September 2013. Accessed September 15, 2017.

- 24.American Academy of Otolaryngologists–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation. AAO-HNS/F code for interaction with companies. https://www.entnet.org/sites/default/files/Code%20for%20Interactions%20with%20Companies_approved%2010sept11_0.pdf. September 2011. Accessed March 15, 2017.

- 25.ProPublica. Dollars for Docs. https://projects.propublica.org/docdollars/. Updated November 12, 2017. Accessed September 1, 2017.

- 26.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Natures of payments. https://www.cms.gov/OpenPayments/About/Natures-of-Payment.html. September 2014. Accessed January 14, 2017.

- 27.Merck. Product list. http://www.merck.com/product/home.html. Updated September 28, 2017. Accessed August 9, 2017.

- 28.Meda. Products. http://www.medapharma.us/products/index.html. Updated October 28, 2017. Accessed August 9, 2017.

- 29.Acclarent. Acclarent AERA® eustachian tube balloon dilation system. https://www.acclarent.com/solutions/products/eustachian-tube/aera. Updated March 4, 2016. Accessed August 9, 2017.

- 30.Bekelman JE, Li Y, Gross CP. Scope and impact of financial conflicts of interest in biomedical research: a systematic review. JAMA. 2003;289(4):454-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chren MM, Landefeld CS. Physicians’ behavior and their interactions with drug companies: a controlled study of physicians who requested additions to a hospital drug formulary. JAMA. 1994;271(9):684-689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson TS, Dave S, Good CB, Gellad WF. Academic medical center leadership on pharmaceutical company boards of directors. JAMA. 2014;311(13):1353-1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kesselheim AS, Robertson CT, Siri K, Batra P, Franklin JM. Distributions of industry payments to Massachusetts physicians. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(22):2049-2052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campbell EG, Weissman JS, Ehringhaus S, et al. . Institutional academic industry relationships. JAMA. 2007;298(15):1779-1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anderson TS, Good CB, Gellad WF. Prevalence and compensation of academic leaders, professors, and trustees on publicly traded US healthcare company boards of directors: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2015;351:h4826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Association of American Medical Colleges Task Force. Industry Funding of Medical Education: Report of an AAMC Task Force. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2008:22. [Google Scholar]

- 37.American Medical Association AMA Conflict of Interest Policy. https://www.ama-assn.org/ama-conflict-interest-policy. Accessed September 1, 2017.

- 38.Pisano ED, Golden RN, Schweitzer L. Conflict of interest policies for academic health system leaders who work with outside corporations. JAMA. 2014;311(11):1111-1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosenfeld RM, Shiffman RN, Robertson P; Department of Otolaryngology State University of New York Downstate . Clinical Practice Guideline Development Manual, Third Edition: a quality-driven approach for translating evidence into action. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;148(1 suppl):S1-S55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neuman J, Korenstein D, Ross JS, Keyhani S. Prevalence of financial conflicts of interest among panel members producing clinical practice guidelines in Canada and United States: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2011;343:d5621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steinbrook R. Guidance for guidelines. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(4):331-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.World Health Organization WHO Handbook for Guideline Development. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 43.American College of Radiology. Conflict of Interest Policy for the American College of Radiology. https://www.acr.org/~/media/ACR/.../ACR-FCOI-Policy-and-Disclosure-Form.docx. Accessed June 21, 2017.

- 44.Department of Health and Human Services The final rule. https://www.cms.gov/OpenPayments/Downloads/Affordable-Care-Act-Section-6002-Final-Rule.pdf. February 8, 2013. Accessed March 15, 2017.

- 45.Resneck JS., Jr Transparency associated with interactions between industry and physicians: deficits in accuracy and consistency of public data releases. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(12):1303-1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Santhakumar S, Adashi EY. The Physician Payment Sunshine Act: testing the value of transparency. JAMA. 2015;313(1):23-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]