Abstract

This study describes the experience of a large integrated health system and provides in-depth descriptions of individuals who initiated the California End of Life Option Act process.

The California End of Life Option Act (EOLOA),1 which took effect on June 9, 2016, allows qualified adults diagnosed with a terminal disease to request aid-in-dying drugs from their physician. The California Department of Public Health recently published data on 191 individuals who received aid-in-dying prescriptions during the act’s first 6 months.2 In response to recommendations for more comprehensive documentation of EOLOA implementation to improve end-of-life care,3 this study describes the experience of a large integrated health system and provides in-depth descriptions of individuals who initiated the EOLOA process.

Methods

This study was based in Kaiser Permanente Southern California using data from June 9, 2016, through June 30, 2017, with follow-up through August 20, 2017. An executive EOLOA task force was formed 7 months prior to the EOLOA taking effect with representatives from bioethics, operations, quality, psychiatry, pharmacy, education, nursing, legal, and palliative care to ensure appropriate policy and structures were in place. Key implementation steps included the following: physicians were surveyed about their willingness to participate after viewing an educational video; staff were trained regarding how to manage EOLOA requests; additional training was provided for volunteer physicians; volunteer pharmacists were identified to dispense and provide education on proper use of the medications; and training was provided for dedicated EOLOA-licensed clinical social work coordinators. The primary responsibilities of the EOLOA coordinators were to provide assistance with navigation to patients, perform psychosocial assessments, serve as a resource for health care professionals involved in the care of these patients, ensure the integrity of informed consent and compliance with the legal requirements, and be available for staff debriefing after patient deaths. Data for this study were obtained from electronic medical records, logs maintained by the EOLOA coordinators, and standard state reporting forms. The study was approved by the Kaiser Permanente Southern California institutional review board and informed consent was waived owing to the retrospective nature of the study. Descriptive statistics were performed with SAS statistical software (version 9.3, SAS Institute, Inc).

Results

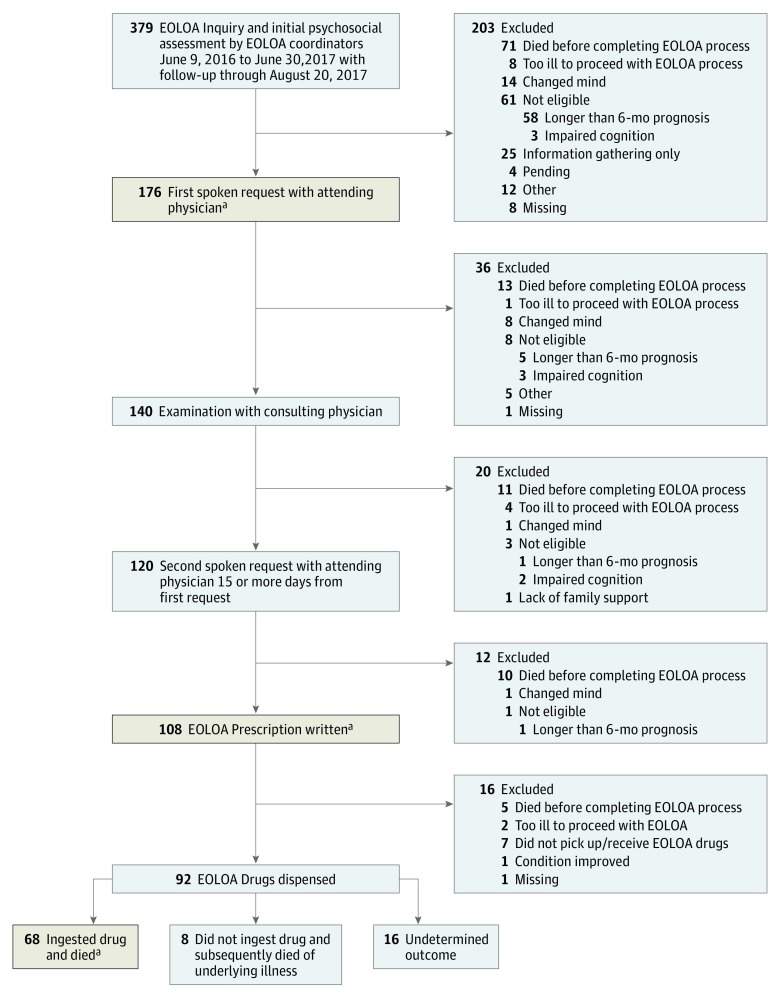

A total of 379 patients initiated an inquiry from June 9, 2016, through June 30, 2017 (Figure). Of these, 79 (21%) patients died or were too ill to proceed, 61 (16%) were ineligible, and 176 (46%) who were deemed eligible proceeded with their first spoken request to an attending physician. Many of the withdrawals at each step of the EOLOA process were owing to death or patients being too ill. Sixty-eight (74%) of the 92 patients who received the EOLOA drugs ingested them and died within a median of 9 days after the prescription was written. The sociodemographic, clinical, and end-of-life care characteristics of patients who completed the first oral request, proceeded to receive a prescription for the aid-in-dying drugs, and ingested the drugs were for the most part similar (Table). Most patients who initiated EOLOA had cancer (74%) and received care primarily from specialists in the previous 12 months. Ninety-six (55%) patients had an activities of daily living impairment and were on palliative care or hospice at the time of their inquiry. The 2 most common reasons patients cited for pursuing EOLOA were that they did not want to suffer and that they were no longer able to participate in activities that made life enjoyable.

Figure. Patient Flow Through the EOLOA Process.

EOLOA Indicates California End of Life Option Act.

aPatients who completed the 3 key steps in the EOLOA process (tan shaded boxes) are described in Table 1.

Table. Characteristics of Patients Who Completed 3 Key Steps in the EOLOA Process.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Completed First Oral

Request (n = 176) |

Prescribed EOLOA

Drugs (n = 108) |

Ingested EOLOA

Drugs (n = 68) |

|

| Age at time of death, median (IQR), y | 69 (62-79) | 69 (62-79) | 69 (62-80) |

| 18-34 | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| 35-54 | 11 (6) | 7 (6) | 4 (6) |

| 55-64 | 46 (26) | 31 (29) | 22 (32) |

| 65-74 | 49 (28) | 30 (28) | 17 (25) |

| 75-84 | 45 (26) | 25 (23) | 14 (21) |

| ≥85 | 23 (13) | 15 (14) | 11 (16) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 99 (56) | 61 (56) | 39 (57) |

| Female | 77 (44) | 47 (44) | 29 (43) |

| Race | |||

| White | 141 (80) | 88 (81) | 52 (76) |

| Hispanic | 17 (10) | 9 (8) | 7 (10) |

| Black/African American | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Asian | 13 (7) | 8 (7) | 7 (10) |

| Multirace | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Marital status | |||

| Married/partnered | 86 (49) | 56 (52) | 32 (47) |

| Unpartnered | 80 (45) | 46 (43) | 33 (49) |

| Missing | 10 (6) | 6 (6) | 3 (4) |

| Social support | |||

| Lives with others | 116 (66) | 69 (64) | 45 (66) |

| Patient informed family of EOLOA decision | 155 (88) | 100 (93) | 64 (94) |

| Education (census based) | |||

| <High school | 20 (11) | 12 (11) | 8 (12) |

| High school | 90 (51) | 55 (51) | 35 (51) |

| College | 64 (36) | 40 (37) | 26 (38) |

| Unknown | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Income (census based), $ | |||

| <20 000 | 24 (14) | 14 (13) | 9 (13) |

| 20 000-49 999 | 40 (23) | 25 (23) | 15 (22) |

| 50 000-74 999 | 28 (16) | 17 (16) | 11 (16) |

| 75 000-149 999 | 51 (29) | 31 (29) | 20 (30) |

| ≥150 000 | 31 (18) | 20 (18) | 12 (17) |

| English speaking | 164 (93) | 102 (94) | 63 (93) |

| Insurance coverage | |||

| Medicare | 115 (65) | 69 (64) | 41 (60) |

| Medicaid | 5 (3) | 0 | 0 |

| Commercial | 41 (23) | 30 (28) | 23 (34) |

| Private pay/other | 14 (8) | 8 (7) | 4 (6) |

| Unknown | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Clinical and functional characteristics | |||

| Disease burden | |||

| Charlson comorbidity index, mean (SD) | 9.3 (4.26) | 9.2 (4.46) | 9.4 (4.63) |

| Quartile 1 (0-6) | 44 (25) | 28 (26) | 18 (26) |

| Quartile 2 (7-9) | 44 (25) | 27 (25) | 17 (25) |

| Quartile 3 (10-12) | 50 (28) | 31 (29) | 17 (25) |

| Quartile 4 (≥13) | 36 (20) | 20 (19) | 15 (22) |

| Underlying terminal diagnosis | |||

| ALS | 9 (5) | 7 (6) | 5 (7) |

| Cancer | 130 (74) | 82 (76) | 52 (76) |

| Genitourinary | 23 (13) | 14 (13) | 11 (16) |

| Lung | 23 (13) | 13 (12) | 8 (12) |

| Gastrointestinal | 18 (10) | 9 (8) | 7 (10) |

| Head/neck | 18 (10) | 13 (12) | 7 (10) |

| Pancreas | 14 (8) | 10 (9) | 6 (9) |

| Breast | 11 (6) | 8 (7) | 4 (6) |

| Other | 23 (13) | 15 (14) | 9 (13) |

| CHF | 7 (4) | 4 (4) | 3 (4) |

| COPD/Other pulmonary conditions | 12 (7) | 6 (6) | 2 (3) |

| MS | 4 (2) | 3 (3) | 2 (3) |

| Parkinson | 3 (2) | 2 (2) | 0 |

| Other illnesses | 7 (4) | 3 (3) | 3 (4) |

| Unknown | 4 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Functional status at time of inquirya | |||

| ADL Impairment | 96 (55) | 55 (51) | 37 (54) |

| Instrumental ADL impairment | 43 (24) | 23 (21) | 15 (22) |

| End-of-life concerns at time of inquiryb | |||

| Does not want to suffer | 110 (63) | 76 (70) | 45 (66) |

| Unable to enjoy daily activities | 97 (55) | 62 (57) | 40 (59) |

| Loss of autonomy | 36 (20) | 24 (22) | 10 (15) |

| Burden on family/friends | 38 (22) | 23 (21) | 16 (24) |

| Inadequate pain control or concern about it | 36 (20) | 23 (21) | 19 (28) |

| Loss of dignity | 24 (14) | 17 (16) | 14 (21) |

| Other (eg, financial concerns) | 16 (9) | 9 (8) | 6 (9) |

| Timing of EOLOA processes, median (IQR), days | |||

| Timing from inquiry to first oral request | 7 (3-14) | 7 (3-14) | 7 (2-13) |

| Timing from inquiry to second oral request | 26 (20-35) | 27 (20-38) | 24 (18-33) |

| Timing from first to second oral request | 17 (15-20) | 17 (15-21) | 16 (15-18) |

| Timing from prescription to ingestion/death | NA | NA | 9 (7-85) |

| Care near the end of life, median (IQR) | |||

| Primary care visits in 12 months prior to inquiry | 3 (2-8) | 3 (1-8) | 4 (2-8) |

| Specialist care visits in 12 months prior to inquiry | 13 (6-28) | 14 (6-29) | 14 (6-27) |

| Palliative care (outpatient or home-based) | |||

| At time of inquiry | 84 (48) | 55 (51) | 34 (50) |

| Ever | 109 (62) | 70 (65) | 43 (63) |

| Length of time since first exposure to PC services prior to inquiry, median (IQR), daysc | 92 (22-338) | 110 (28-391) | 103 (72-397) |

| Hospice care | |||

| At time of inquiry | 84 (48) | 52 (48) | 38 (56) |

| Ever | 139 (79) | 86 (80) | 59 (87) |

| Length of time on hospice prior to inquiry, median (IQR), daysc | 16 (5-60) | 16 (4-75) | 23 (4-65) |

| Advance care planning on record at inquiry | |||

| Advance directive | 108 (61) | 68 (63) | 43 (63) |

| POLST | 88 (50) | 53 (49) | 33 (49) |

| Code status at inquiry | |||

| Full code | 72 (41) | 42 (39) | 24 (35) |

| DNR | 73 (42) | 46 (43) | 32 (47) |

| Missing | 31 (18) | 20 (19) | 12 (18) |

| Death location | |||

| Home/home hospice | 170 (97) | 106 (98) | 68 (100) |

| Hospital/ED/SNF/other | 6 (3) | 2 (2) | 0 |

Abbreviations: ADL, activities of daily living; ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DNR, do not resuscitate; ED, emergency department; EOLOA, California End of Life Option Act; IQR, interquartile range; MS, multiple sclerosis; SNF, skilled nursing facility; POLST, provider orders for life-sustaining treatment.

For the 3 respective column categories, activities of daily living missing for 24 (14%), 11 (10%), and 6 (9%); instrumental ADL, missing for 35 (20%), 17 (16%), and 10 (15%).

Patients could endorse multiple reasons at the time of their initial inquiry and reasons could change during the EOLOA process but this was not captured in this analysis.

Length of palliative care or hospice service only for patients who received palliative care or hospice prior to inquiry.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first detailed report describing the outcome and characteristics of all individuals who initiated the EOLOA process from a large health care system in California. The characteristics of this sample were similar to a recent report2 with the exception that a higher percentage of these patients proceeded with ingesting the aid-in-dying drugs (75% vs 59%); this may be owing to the longer follow-up time. Similar to Oregon’s experience,4 patients’ end-of-life concerns appear difficult to palliate with the most common cited reasons for pursuing EOLOA being existential suffering, inability to enjoy life, and loss of autonomy.

References

- 1.Assembly Bill No 15 (End of Life). 2015; https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201520162AB15. Accessed August 29, 2017.

- 2.California End of Life Option Act: 2016 Data Report. https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CHSI/CDPH%20Document%20Library/CDPH%20End%20of%20Life%20Option%20Act%20Report.pdf. Accessed August 29, 2017.

- 3.Cain CL. Implementing Aid in Dying in California: Experiences from Other States Indicates the Need for Strong Implementation Guidance. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanke C, LeBlanc M, Hershman D, Ellis L, Meyskens F. Characterizing 18 years of the death with dignity act in oregon. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(10):1403-1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Typographic error in Figure [published online February 5, 2018]. JAMA Intern Med. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]