Key Points

Question

How do tear film stability measurements obtained with an automated noninvasive keratograph corneal topographer compare with the conventional fluorescein method?

Findings

In an investigator-masked randomized crossover trial of 74 participants, fluorescein breakup time measurements were shorter and more narrowly distributed than those from automated noninvasive keratograph measurements. The keratograph had superior discriminative ability and diagnostic accuracy in detecting dry eye.

Meaning

The results suggest that the automated noninvasive technique may be a more sensitive method of measuring tear film stability for dry eye evaluation.

Abstract

Importance

Tear film breakup time assessment is an integral component of dry eye evaluation. To our knowledge, the comparative discriminative ability of the noninvasive Keratograph (Oculus) vs conventional fluorescein method in detecting dry eye is unknown.

Objective

To compare tear film stability measurements obtained with an automated noninvasive corneal topographer vs conventional fluorescein methods and evaluate their respective discriminative ability in detecting dry eye.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This investigator-masked randomized crossover trial was conducted at a single-center university clinic between May 26, 2016, and October 3, 2016, and included 74 participants 18 years or older. Participants were recruited into 2 equally sized age, sex, and race/ethnicity–matched groups, with and without symptomatic dry eye (Ocular Surface Disease Index ≥13).

Interventions

Participants were assigned to receive a noninvasive keratograph evaluation and topical fluorescein instillation in a randomized order.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Noninvasive keratograph breakup time (NIKBUT) and fluorescein breakup time (TBUT). Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, Youden-optimal diagnostic cutoff sensitivity, and specificity of NIKBUT and TBUT in detecting dry eye.

Results

Seventy-four participants (74 eyes; 43 women [58.1%]) with a mean (SD) age of 24 (4) years were randomized. Noninvasive keratograph breakup time was significantly longer than TBUT in participants with dry eye (median, 6.3 seconds vs 4.3 seconds [difference, 2.0 seconds]; 95% CI, 1.1-3.4 seconds; P = .003), and healthy participants (median, 11.9 seconds vs 5.0 seconds [difference, 6.9 seconds]; 95% CI, 4.7-7.6 seconds; P < .001). Fluorescein breakup time measurements were more narrowly distributed in both the dry eye (variance, 188 seconds2 vs 27.9 seconds2; P < .001) and control groups (variance, 113 seconds2 vs 13.4 seconds2; P < .001). The discriminative ability of NIKBUT in detecting dry eye (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.56-0.81; P = .007) was greater than that of TBUT (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.44-0.70; P = .31). The optimal diagnostic cutoff for NIKBUT was 9 seconds or less with a sensitivity of 68% (95% CI, 50%-82%), specificity of 70% (95% CI, 53%-84%), positive likelihood ratio of 2.27 (95% CI, 1.32-3.91), and negative likelihood ratio of 0.46 (95% CI, 0.28-0.77). The optimal threshold for TBUT was 5 seconds or less with a sensitivity of 54% (95% CI, 37%-71%), specificity of 68% (95% CI, 50%-82%), positive likelihood ratio of 1.67 (95% CI, 0.96-2.89), and negative likelihood ratio of 0.68 (95% CI, 0.45-1.03).

Conclusions and Relevance

Conventional fluorescein tear film breakup time measurements were significantly shorter with narrower distributions, while automated noninvasive keratograph readings displayed superior discriminative ability in detecting dry eye.

Trial Registration

anzctr.org.au Identifier: ACTRN12617001428358

This randomized crossover trial compares the discriminative ability of an automated noninvasive keratograph corneal topographer technique vs the fluorescein method to detect dry eye.

Introduction

Tear film breakup time measurement is a central component of dry eye assessment. Although topical instillation of sodium fluorescein via impregnated strips is commonly used to visualize breakup, it is recognized that it reduces tear film stability.

Recently, the Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society Dry Eye Workshop (TFOS DEWS II) recommended using automated noninvasive measurement techniques that allow for an objective assessment of the undisturbed tear film. The Keratograph 5M (Oculus) is a noninvasive corneal topographer that measures noninvasive breakup time by detecting distortion in the contours of reflected Placido disc mires using an automated real-time videokeratoscopy analysis. The noninvasive technique may potentially be superior to the conventional fluorescein method by avoiding the tear film destabilization that is associated with fluorescein instillation. This randomized study sought to compare clinical tear film stability measurements obtained from the automated noninvasive keratograph with conventional fluorescein methods and evaluate their respective discriminative ability in detecting dry eye.

Methods

This investigator-masked randomized crossover study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and received institutional ethics committee approval from the University of Auckland. The trial protocol is available in the Supplement. Participants were required to be 18 years or older with no history of uncontrolled major systemic disease, surgical procedures, or use of systemic/topical medications known to affect the eye within 3 months of study participation. Seventy-four participants provided written consent and were randomized into 2 equally sized age, sex, and race/ethnicity–matched groups, with and without symptomatic dry eye, between May 26, 2016, and October 3, 2016. This satisfied nonparametric power calculations (n = 62, β = 0.2, α = .05, difference = 5 seconds, SD = 7 seconds). Symptomatic dry eye classification was made according to an Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) score of 13 or greater.

Two independent observers measured right eye tear film breakup time in triplicate, respectively, in a randomized order (Figure 1), using noninvasive automated keratograph readings (noninvasive keratograph breakup time [NIKBUT]), and under blue light with a Wratten yellow filter following instillation of a drop (approximately 10 μl) of fluorescein from a wetted impregnated strip (Haag-Streit) that was shaken to remove excess fluid (fluorescein breakup time [TBUT]). A 30-minute interval between measurements ensured subsidence of reflex tearing.

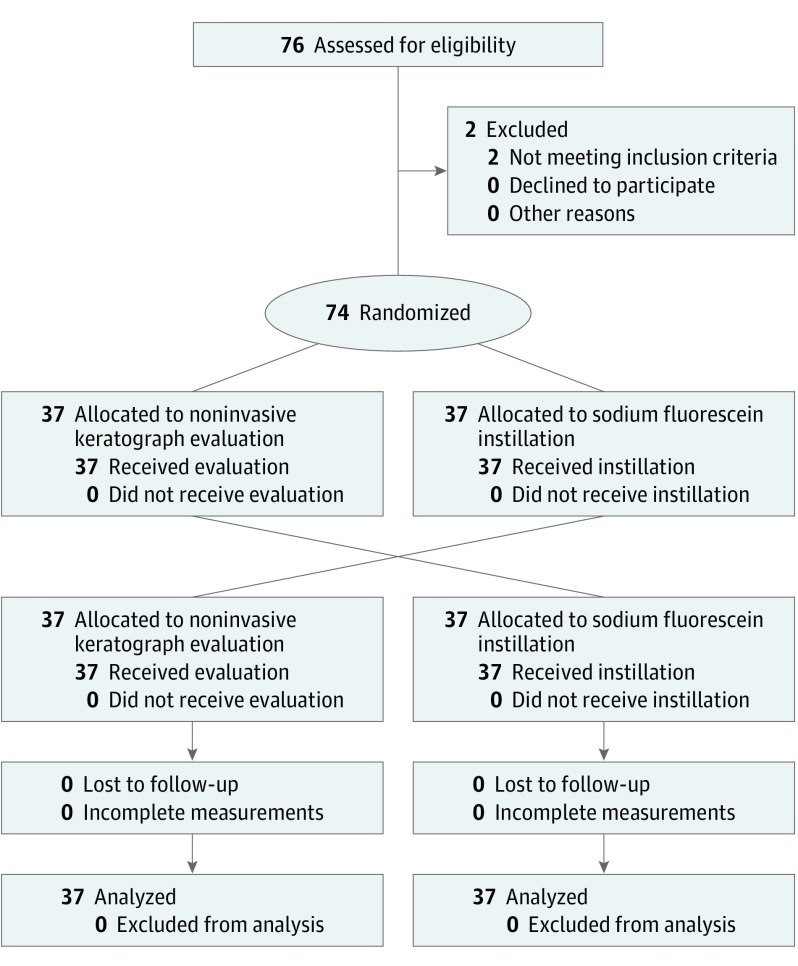

Figure 1. Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials 2010 Flow Diagram.

Participant allocation and crossover to noninvasive keratograph evaluation and topical sodium fluorescein instillation.

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism, version 6.02 (GraphPad). Non-normally distributed NIKBUT and TBUT measurements were logarithmically transformed to fulfill D’Agostino-Pearson normality testing before the parametric analysis. Intragroup and intergroup comparisons were conducted with paired and unpaired t tests, respectively, and variances were analyzed by F tests. A Bland-Altman analysis between stability measurements and a Pearson correlation analysis with OSDI were performed. Receiver operator characteristic curves were constructed to assess the discriminative ability of the 2 measurements in detecting dry eye. The area under the curve (C statistic), and Youden-optimal diagnostic cutoff sensitivity and specificity were then calculated. All tests were 2-tailed, and P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

Seventy-four participants (74 eyes; 43 women [58.1%]; 29 European [39.2%] and 45 East Asian [60.8%]) with a mean (SD) age of 24 (4) years were recruited (Table). Tear film stability measurements obtained from NIKBUT were significantly longer than TBUT in both participants with dry eye (median, 6.3 seconds vs 4.3 seconds [difference, 2.0 seconds]; 95% CI, 1.1-3.4 seconds; P = .003), and healthy participants (median, 11.9 seconds vs 5.0 seconds [difference 6.9 seconds]; 95% CI, 4.7-7.6 seconds; P < .001). Fluorescein breakup time measurements were more narrowly distributed in both the dry eye (variance, 188 seconds2 vs 27.9 seconds2; P < .001) and control groups (variance, 113 seconds2 vs 13.4 seconds2; P < .001). Participants with dry eye had shorter NIKBUT than those without (median, 6.3 seconds vs 11.9 seconds [difference, −5.6 seconds]; 95% CI, −1.7 seconds to −7.8 seconds; P = .01), but no difference was detected for TBUT (median, 4.3 seconds vs 5.0 seconds [difference, −1.3 seconds]; 95% CI, −2.3 seconds to 1.0 seconds; P = .26).

Table. Characteristics and Measurements of Participants With and Without Dry Eye.

| Characteristic | Dry Eye (n = 37) | Control (n = 37) |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 24 (4) | 23 (4) |

| Male, No. (%) | 15 (41) | 16 (43) |

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | ||

| European | 14 (38) | 15 (41) |

| East Asian | 23 (62) | 22 (59) |

| OSDI score, mean (SD) | 25.1 (8.7) | 6.0 (4.4) |

| Tear film stability measurements, median (95% CI), s | ||

| NIKBUT | 6.3 (4.4-9.7) | 11.9 (9.4-14.6) |

| TBUT | 4.3 (3.3-6.3) | 5.0 (4.7-7.0) |

| Difference between NIKBUT and TBUT | 2.0 (1.1-3.4) | 6.9 (4.7-7.6) |

| Comparison of log (NIKBUT) vs log (TBUT) | ||

| Paired t test, P value | .003 | <.001 |

| F test of variances, P value | <.001 | <.001 |

| Pearson correlation coefficient (95% CI) | 0.42 (0.09-0.67) | 0.55 (0.29-0.73) |

| Correlation significance, P value | .001 | <.001 |

| Bland-Altman bias (95% LoA) | 0.20 (−0.52 to 0.91) | 0.33 (−0.24 to 0.91) |

Abbreviations: LoA, limits of agreement; NIKBUT, noninvasive keratograph tear film breakup time; OSDI, Ocular Surface Disease Index; TBUT, conventional fluorescein tear film breakup time.

Significant positive correlations were observed between NIKBUT and TBUT in both the dry eye group (Pearson r = 0.42; 95% CI, 0.09-0.67; P = .001) and the controls (Pearson r, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.29-0.73; P < .001). Reverse transformation of Bland-Altman biases showed that, on average, NIKBUT was 1.6 (95% limits of agreement, 0.3-8.1) times that of TBUT in dry eye, and 2.1 (95% limits of agreement, 0.6-8.1) times in healthy participants. The OSDI score was significantly correlated with both NIKBUT (Pearson r, −0.32; 95% CI, −0.51 to −0.10, P = .005) and TBUT (Pearson r, −0.26; 95% CI, −0.46 to −0.03; P = .03).

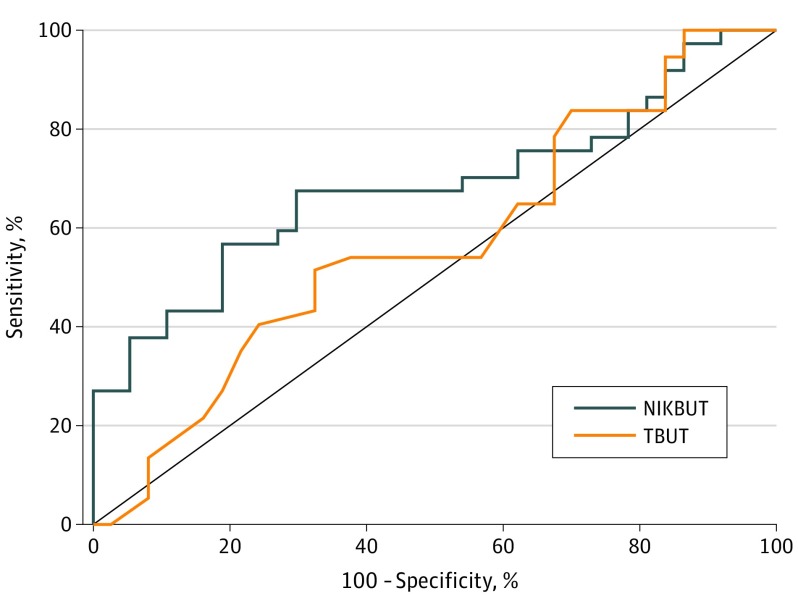

Receiver operator characteristic curves for the discriminative ability of NIKBUT and TBUT in detecting dry eye are illustrated in Figure 2. The discriminative ability of NIKBUT (C statistic, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.56-0.81, P = .007) was greater than that of TBUT (C statistic, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.44-0.70; P = .31).

Figure 2. Receiver Operating Characteristic Curves of Discriminative Ability to Detect Dry Eye.

Measured for noninvasive keratograph breakup time (NIKBUT) and conventional fluorescein tear film breakup time (TBUT).

The optimal diagnostic cutoff for NIKBUT was 9 seconds or less with a sensitivity of 68% (95% CI, 50%-82%), specificity of 70% (95% CI, 53%-84%), positive likelihood ratio of 2.27 (95% CI, 1.32-3.91), and negative likelihood ratio of 0.46 (95% CI, 0.28-0.77). The optimal threshold for TBUT was 5 seconds or less with a sensitivity of 54% (95% CI, 37%-71%), specificity of 68% (95% CI, 50%-82%), positive likelihood ratio of 1.67 (95% CI, 0.96-2.89), and negative likelihood ratio of 0.68 (95% CI, 0.45-1.03).

Discussion

The results demonstrate significantly shorter and more narrowly distributed TBUT than NIKBUT measurements in both participant groups. Noninvasive keratograph breakup time displayed greater discriminative ability in detecting dry eye than did TBUT.

Strengths and Limitations

This study is not without limitations. Predominantly younger East Asian and European participants were recruited, and eligibility required participants to have no uncontrolled major systemic disease, surgical procedures, or topical/systemic medication use known to affect the eye within 3 months of study participation. This may affect the applicability of study findings to other demographic populations or to the secondary and iatrogenic dry eye conditions that were excluded.

Nevertheless, the median NIKBUT measurements were significantly longer than TBUT measurements, consistent with previously reported tear film destabilization effects of fluorescein instillation. Interestingly, the difference was smaller in participants with dry eye, which may be associated with the positively skewed nature of both measurements. This was supported by a Bland-Altman analysis that showed that NIKBUT was, on average, 1.6 and 2.1 times TBUT in the dry eye and control groups.

The distributions of TBUT measurements were narrower than NIKBUT with smaller interparticipant variability, potentially reflecting a global reduction of stability measurements following fluorescein instillation. This global reduction may also contribute toward the significant correlations that were observed between NIKBUT and TBUT, which were concordant with an earlier report. However, in both groups, the relatively wide Bland-Altman limits of agreement suggested poorer levels of clinical agreement between the 2 measurements. Interestingly, the limits of agreement were narrower than those reported in a previous study that compared NIKBUT with stability measurements following micropipette instillation of a smaller volume of fluorescein (5 μl). Differences in reflex tearing and fluorescein concentrations achieved by micropipette instillation may potentially have contributed.

To our knowledge, the comparative discriminative abilities of NIKBUT vs TBUT in detecting dry eye have not been previously established. In the current study, NIKBUT displayed superior discriminative ability with a greater C statistic, higher optimal diagnostic accuracy, and stronger correlation with OSDI scores. Furthermore, a significant difference in NIKBUT, but not TBUT, was detected between participants reporting dry eye and healthy participants. Interestingly, although the optimal diagnostic cutoff for NIKBUT (≤9 seconds) reflected the recommendations from the TFOS DEWS II (<10 seconds), the optimal threshold for TBUT was significantly lower (≤5 seconds). The superior discriminative ability of NIKBUT may be related to the lesser degree of overlap in the 95% CIs between participant groups. Nonetheless, the small intergroup overlap in the 95% CIs of NIKBUT was likely to contribute to the modest sensitivity and specificity values of around 70%. This may reflect the complex interrelationship between tear film function, ocular surface inflammation, and somatosensory pathways in dry eye development.

Conclusions

Conventional fluorescein tear film stability measurements were significantly shorter with narrower distributions, while automated noninvasive keratograph readings demonstrated superior discriminative ability in detecting dry eye.

Trial Protocol.

References

- 1.Wolffsohn JS, Arita R, Chalmers R, et al. TFOS DEWS II diagnostic methodology report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):539-574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith J, Nichols KK, Baldwin EK. Current patterns in the use of diagnostic tests in dry eye evaluation. Cornea. 2008;27(6):656-662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mooi JK, Wang MTM, Lim J, Müller A, Craig JP. Minimising instilled volume reduces the impact of fluorescein on clinical measurements of tear film stability. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2017;40(3):170-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller KL, Walt JG, Mink DR, et al. Minimal clinically important difference for the ocular surface disease index. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128(1):94-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peterson RC, Wolffsohn JS, Fowler CW. Optimization of anterior eye fluorescein viewing. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142(4):572-575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1(8476):307-310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stapleton F, Alves M, Bunya VY, et al. TFOS DEWS II epidemiology report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):334-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gomes JAP, Azar DT, Baudouin C, et al. TFOS DEWS II iatrogenic report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):511-538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cox SM, Nichols KK, Nichols JJ. Agreement between automated and traditional measures of tear film breakup. Optom Vis Sci. 2015;92(9):e257-e263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bron AJ, de Paiva CS, Chauhan SK, et al. TFOS DEWS II pathophysiology report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):438-510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belmonte C, Nichols JJ, Cox SM, et al. TFOS DEWS II pain and sensation report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):404-437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vehof J, Kozareva D, Hysi PG, et al. Relationship between dry eye symptoms and pain sensitivity. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131(10):1304-1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galor A, Levitt RC, McManus KT, et al. Assessment of somatosensory function in patients with idiopathic dry eye symptoms. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134(11):1290-1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ong ES, Alghamdi YA, Levitt RC, et al. Longitudinal examination of frequency of and risk factors for severe dry eye symptoms in US veterans. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;135(2):116-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol.