Abstract

Importance

Prevalence of persistent central-involved diabetic macular edema (DME) through 24 weeks of anti–vascular endothelial growth factor therapy and its longer-term outcomes may be relevant to treatment.

Objective

To assess outcomes of DME persisting at least 24 weeks after randomization to treatment with 2.0-mg aflibercept, 1.25-mg bevacizumab, or 0.3-mg ranibizumab.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Post hoc analyses of a clinical trial, the DRCR.net Protocol T among 546 of 660 participants (82.7%) meeting inclusion criteria for this investigation.

Interventions

Six monthly intravitreous anti–vascular endothelial growth factor injections (unless success after 3 to 5 injections); subsequent injections or focal/grid laser as needed per protocol to achieve stability.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Persistent DME through 24 weeks, probability of chronic persistent DME through 2 years, and at least 10-letter (≥ 2-line) gain or loss of visual acuity.

Results

The mean age of participants was 60 years, 363 (66.5%) were white, and 251 (46.0%) were women. Persistent DME through 24 weeks was more frequent with bevacizumab (118 of 180 [65.6%]) than aflibercept (60 of 190 [31.6%]) or ranibizumab (73 of 176 [41.5%]) (aflibercept vs bevacizumab, P < .001; ranibizumab vs bevacizumab, P < .001; and aflibercept vs ranibizumab, P = .05). Among eyes with persistent DME through 24 weeks (n = 251), rates of chronic persistent DME through 2 years were 44.2% with aflibercept, 68.2% with bevacizumab (aflibercept vs bevacizumab, P = .03), and 54.5% with ranibizumab (aflibercept vs ranibizumab, P = .41; bevacizumab vs ranibizumab, P = .16). Among eyes with persistent DME through 24 weeks, proportions with vs without chronic persistent DME through 2 years gaining at least 10 letters from baseline were 62% of 29 eyes vs 63% of 30 eyes (P = .88) with aflibercept, 51% of 70 vs 55% of 31 (P = .96) with bevacizumab, and 45% of 38 vs 66% of 29 (P = .10) with ranibizumab. Only 3 eyes with chronic persistent DME lost at least 10 letters.

Conclusions and Relevance

Persistent DME was more likely with bevacizumab than with aflibercept or ranibizumab. Among eyes with persistent DME, eyes assigned to bevacizumab were more likely to have chronic persistent DME than eyes assigned to aflibercept. These results suggest meaningful gains in vision with little risk of vision loss, regardless of anti–vascular endothelial growth factor agent given or persistence of DME through 2 years. Caution is warranted when considering switching therapies for persistent DME following 3 or more injections; improvements could be owing to continued treatment rather than switching therapies.

Trial Registration

clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT01627249

Key Points

Question

What is the prevalence of persistent central-involved diabetic macular edema through 24 weeks and subsequent outcomes using different anti–vascular endothelial growth factor drugs?

Findings

In this post hoc analysis of a clinical trial, persistent diabetic macular edema through 24 weeks was less likely with 2.0-mg aflibercept or 0.3-mg ranibizumab than 1.25-mg bevacizumab, and among eyes with persistent DME through 24 weeks, chronic persistent diabetic macular edema through 2 years was more likely with bevacizumab than aflibercept. Regardless of diabetic macular edema persistence or anti–vascular endothelial growth factor agent, few eyes lost substantial vision.

Meaning

Using this protocol, at least 2-line visual acuity loss was uncommon through 2 years with any of these anti–vascular endothelial growth factor agents, even when diabetic macular edema chronically persisted.

This secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial assesses outcomes of diabetic macular edema persisting at least 24 weeks after randomization to treatment with 2.0-mg aflibercept, 1.25-mg bevacizumab, or 0.3-mg ranibizumab.

Introduction

Anti–vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) injections are typically standard care for eyes with central-involved diabetic macular edema (DME) and vision impairment.1 Despite the positive effects of anti-VEGF injections on both visual acuity and retinal thickening, DME can persist in some eyes. An exploratory analysis of data from Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network (DRCR.net) Protocol I investigated the frequency of persistent DME through 24 weeks and whether chronic persistent DME had deleterious effects on visual acuity outcomes through 3 years.2,3 Approximately 40% of eyes receiving monthly ranibizumab had persistent DME through 24 weeks. As these eyes continued treatment, applying a protocol based on changes in visual acuity and optical coherence tomography, the percentage of patients with chronic persistent DME (ie, never resolving at 2 consecutive visits) was 55.8% and 40.1% at the 2-year and 3-year visits, respectively. Visual acuity outcomes appeared slightly less favorable among the eyes in which DME persisted through 3 years; however, visual acuity typically improved from baseline, and substantial (≥ 2-line) loss was uncommon. The DRCR.net retreatment algorithm treats DME to stability (2 consecutive visits without improvement or worsening of vision and central subfield thickness [CST]), not resolution.

To further our understanding of the prevalence of persistent DME and its effect on visual acuity across different anti-VEGF agents, the DRCR.net conducted a similar post hoc analysis of eyes treated for DME with aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab in a randomized comparative effectiveness trial (Protocol T). In Protocol T, all 3 agents, on average, improved vision, but the relative effect depended on baseline visual acuity.4 Specifically, when the initial visual acuity was 20/32 to 20/40 (approximate Snellen equivalent), on average, there were no apparent differences in mean change in visual acuity from baseline to 1 or 2 years. However, when visual acuity was 20/50 to 20/320, aflibercept was more effective at improving vision.

Methods

The methods for the DRCR.net Protocol T clinical trial have been published in detail elsewhere, with the complete protocol available online.4 The study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Study participants provided written informed consent. The protocol and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant informed consent forms were approved by institutional review boards at all participating sites. Principal eligibility criteria included eyes with central-involved DME on clinical examination and a best-corrected electronic visual acuity letter score of 78 through 24 (approximate Snellen equivalent 20/32 to 20/320) following a protocol refraction.5

Visits were every 4 weeks through the 52-week visit and every 4, 8, or 16 weeks thereafter, depending on the clinical course. The protocol required injections at baseline and every 4 weeks for the initial 20 weeks unless CST was less than 250 μm (time-domain [Zeiss Stratus] equivalent) and the visual acuity letter score was 84 or better (approximate Snellen equivalent 20/20 or better) after 2 consecutive 4-week injections (Box). Thereafter, injections were repeated every 4 weeks if there was successive improvement or worsening in visual acuity (≥5 letters) or CST (change by ≥10%) and vision remained worse than 20/20, with CST of at least 250 μm. Otherwise, reinjection was withheld starting with the 24-week visit if there was no improvement or worsening of visual acuity or CST after 2 consecutive injections (sustained stability). Injections resumed if there was subsequent worsening of visual acuity or CST until sustained stability of visual acuity and CST were attained. Focal/grid laser was given as needed per protocol at or following the 24-week visit if DME persisted, the eye had not improved in visual acuity or CST from the last 2 consecutive injections, and there were lesions amenable to photocoagulation. Alternative treatments, such as intravitreous corticosteroids, were not permitted unless failure criteria were met.

Box. Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network Principles of Anti-VEGF Treatment Regimen for Diabetic Macular Edema.

-

Six monthly injections unless vision is 20/20 or better and optical coherence tomography (OCT) central subfield thickness (CST) is normal after at least 3 consecutive injections.

For Heidelberg Spectralis machines, normal was defined as central subfield thickness <305 μm for women and <320 μm for men. For Zeiss Cirrus machines, normal was defined as central subfield thickness <290 μm for women and <305 μm for men. For Zeiss Stratus machines, normal was defined as central subfield thickness <250 μm for both sexes.

-

After the 6-month visit, withhold anti-VEGF if visual acuity or OCT CST has neither improved nor worsened compared with the last 2 injection visits, ie, no injection if either of the following scenarios:

Diabetic macular edema (DME) has resolved (“normal” OCT results)

-

Persistent but stable DME in the absence of visual acuity improvement or worsening

Improvement or worsening was defined as OCT central subfield thickness ≥10% change or best-corrected E-ETDRS visual acuity ≥5 letters change (approximately ≥1 line on an ETDRS eye chart)

-

Resume anti-VEGF if either of the following scenarios:

Visual acuity worsens in the setting of persistent but stable DME

Optical coherence tomography CST worsens

-

If there is persistent but stable DME and an injection has been deferred, then add focal/grid laser if indicated. Focal/grid laser is indicated if all of the following criteria are met:

At least 4 months since prior focal/grid laser treatment

Treatable lesions within thickened areas of the macula between 500 and 3000 microns from the center of the macula, including either of the following: previously untreated microaneurysms or areas of thickening without untreated microaneurysms and without prior grid laser treatment at least 1 to 2 burn widths apart.

Abbreviation: VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Among the 660 eyes initially randomized to aflibercept (n = 224), bevacizumab (n = 218), or ranibizumab (n = 218), 114 eyes were excluded from this analysis. This included 14 eyes with baseline CST less than 250 μm, 23 that received less than 4 injections prior to 24 weeks, 47 that missed more than 2 visits between the 28-week and 52-week visits, 6 that received alternative treatment for DME prior to 52 weeks, and 24 that missed the 24-week visit (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). These exclusion criteria are based on those used in the previous analysis of Protocol I data and were determined prior to looking at data from Protocol T. The persistent DME cohort included all eyes that did not meet the exclusion criteria and had CST of at least 250 μm at each completed study visit through 24 weeks. Thereafter, these eyes were labeled as having chronic persistent DME until they achieved a CST less than 250 μm and achieved a reduction of at least 10% in CST relative to the 24-week visit on at least 2 consecutive study visits. To increase the likelihood that eyes were correctly classified with respect to chronic persistent DME between the 52-week and 104-week visits, 14 eyes with fewer than 4 visits completed in the second year (including the 104-week visit) and 4 eyes that received alternative treatment for DME during the second year were excluded from analysis at 2 years.

Treatment-group comparisons of binary outcomes (eg, percentage of eyes gaining 10 or more letters or with persistent DME) were conducted with a generalized linear model adjusting for baseline vision or CST. Within-group comparisons of visual acuity by presence of persistent or chronic persistent DME were conducted with anaylsis of covariance, adjusting for baseline visual acuity. The cumulative probability of chronic persistent DME for each treatment group with corresponding 95% confidence interval was calculated using the life table method, and treatment-group comparisons were conducted with proportional hazards regression adjusting for baseline CST. For between-group comparisons, P values and confidence intervals were adjusted for multiplicity using the Hochberg method.6 Owing to the large number of tests performed, P less than .05 was considered to be suggestive, rather than definitive, evidence of a difference. All P values were 2-sided. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Persistent DME Through 24 Weeks

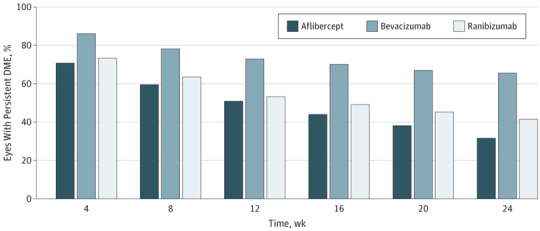

The percentage of eyes with persistent DME at each visit through 24 weeks is shown in Figure 1. At week 12 (after 3 consecutive monthly injections), DME persisted in 50.8% (95 of 187), 72.9% (129 of 177), and 53.2% (91 of 171) of eyes in the aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab groups, respectively. This percentage continued to decrease through 24 weeks (after 3 to 6 consecutive monthly injections), with persistent DME noted in 31.6% (60 of 190), 65.6% (118 of 180), and 41.5% (n = 73 of 176) of eyes. Diabetic macular edema was more likely to persist through 24 weeks with bevacizumab than aflibercept or ranibizumab; adjusted differences were 34.4% (adjusted 95% CI, 23.0% to 45.8%; P < .001) for bevacizumab-aflibercept, 9.5% (adjusted 95% CI, −0.1% to 19.1%; P = .05) for ranibizumab-aflibercept, and 24.9% (adjusted 95% CI, 13.8% to 36.1%; P < .001) for bevacizumab-ranibizumab. Results were similar within the subgroups of eyes with better (20/32 to 20/40) and worse (20/50 to 20/320) baseline visual acuity (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

Figure 1. Persistent Diabetic Macular Edema (DME) Through 24 Weeks .

At 24 weeks, P < .001 for aflibercept vs bevacizumab, P = .05 for aflibercept vs ranibizumab, and P < .001 for ranibizumab vs bevacizumab.

Baseline participant and ocular characteristics are shown in eTable 2 in the Supplement by treatment group and the presence of persistent DME through 24 weeks. Baseline CST was greater among eyes with persistent DME (median values for aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab were 412 μm, 413 μm, and 427 μm with persistent DME vs 365 μm, 327 μm, and 355 μm, respectively, without persistent DME). Regarding injections, eyes with persistent DME through 24 weeks received 4 to 6 injections (median, 6 in all groups) prior to 24 weeks, while eyes without persistent DME received 3 to 6 injections (median, 6 in all groups) because injections could be deferred if success criteria were met after 3 injections.

Changes in visual acuity and CST from baseline to 24 weeks among eyes with and without persistent DME are shown in Table 1. At 24 weeks, mean improvement in visual acuity from baseline was greater among eyes without persistent DME vs those with persistent DME in the aflibercept (adjusted difference, 3.1; 95% CI, 0.7 to 5.5; P = .01) and ranibizumab (adjusted difference, 3.7; 95% CI, 1.4 to 6.0; P = .002) groups, but not in the bevacizumab group (adjusted difference, 0.7; 95% CI, −1.8 to 3.1; P = .59). Mean change in visual acuity from baseline to 104 weeks among eyes with persistent DME through 24 weeks (irrespective of their subsequent anatomic course) was within 1 to 2 letters of eyes without persistent DME through 24 weeks for each treatment group. Among eyes with persistent DME, mean (SD) change in visual acuity from 24 to 104 weeks was 2.5 (9.5), 1.1 (9.3), and 3.4 (9.2) letters in the aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab groups, respectively, indicating that most of the improvement in vision in these eyes occurred in the first 24 weeks. Among eyes without persistent DME, mean change in visual acuity from 24 weeks to 104 weeks was less than 1.5 letters in each group. These outcomes stratified by baseline visual acuity are presented in eTable 3 in the Supplement (20/32 to 20/40) and eTable 4 in the Supplement (20/50 to 20/320).

Table 1. Visual Acuity and OCT Outcomes Through 24 Weeks by Presence of Persistent Diabetic Macular Edema.

| Characteristic | Eyes With Persistent DME Through 24 Weeks | Eyes Without Persistent DME Through 24 Weeks | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aflibercept (n = 60) |

Bevacizumab (n = 118) |

Ranibizumab (n = 73) |

Aflibercept (n = 130) |

Bevacizumab (n = 62) |

Ranibizumab (n = 103) |

|

| Baseline visual acuity | ||||||

| Letter score, median (IQR) | 68 (74 to 60) | 69 (73 to 59) | 69 (73 to 64) | 70 (74 to 59) | 68 (72 to 62) | 69 (73 to 58) |

| Approximate Snellen equivalent, median (IQR) | 20/50 (20/32 to 20/63) | 20/40 (20/40 to 20/63) | 20/40 (20/40 to 20/50) | 20/40 (20/32 to 20/63) | 20/50 (20/40 to 20/63) | 20/40 (20/40 to 20/80) |

| 24-wk Visual acuitya | ||||||

| Letter score, median (IQR) | 78 (83 to 72) | 77 (82 to 68) | 77 (81 to 71) | 79 (85 to 74) | 76 (81 to 72) | 79 (84 to 73) |

| Approximate Snellen equivalent, median (IQR) | 20/32 (20/25 to 20/40) | 20/32 (20/25 to 20/50) | 20/32 (20/25 to 20/40) | 20/25 (20/20 to 20/32) | 20/32 (20/25 to 20/40) | 20/32 (20/20 to 20/40) |

| 20/25 or Better, No. (%) | 29 (48.3) | 47 (39.8) | 25 (34.2) | 68 (52.3) | 19 (30.6) | 51 (50.0) |

| 20/32 to 20/40, No. (%) | 19 (31.7) | 41 (34.7) | 33 (45.2) | 48 (36.9) | 33 (53.2) | 29 (28.4) |

| 20/50 to 20/80, No. (%) | 8 (13.3) | 24 (20.3) | 9 (12.3) | 11 (8.5) | 7 (11.3) | 17 (16.7) |

| 20/100 to 20/160, No. (%) | 3 (5.0) | 4 (3.4) | 5 (6.8) | 3 (2.3) | 3 (4.8) | 5 (4.9) |

| 20/200 or Worse, No. (%) | 1 (1.7) | 2 (1.7) | 1 (1.4) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 24-wk Change in visual acuity letter score from baselinea | ||||||

| Median (IQR) | 9 (5 to 15) | 9 (3 to 14) | 7 (3 to 11) | 12 (6 to 19) | 10 (4 to 14) | 12 (7 to 18) |

| Mean (SD)b | 9.9 (8.8) | 8.8 (8.7) | 8.0 (8.4) | 13.2 (10.0) | 9.6 (8.6) | 12.3 (8.4) |

| ≥15-Letter gain, No. (%)c | 17 (28.3) | 24 (20.3) | 11 (15.1) | 52 (40.0) | 14 (22.6) | 35 (34.3) |

| 10-14–Letter gain, No. (%)c | 10 (16.7) | 32 (27.1) | 16 (21.9) | 30 (23.1) | 18 (29.0) | 27 (26.5) |

| 5-9–Letter gain, No. (%) | 19 (31.7) | 25 (21.2) | 22 (30.1) | 25 (19.2) | 11 (17. 7) | 27 (26.5) |

| Within 4 letters, No. (%) | 12 (20.0) | 32 (27.1) | 21 (28.8) | 22 (16.9) | 15 (24.2) | 11 (10.8) |

| 5-9–Letter loss, No. (%) | 0 | 3 (2.5) | 2 (2.7) | 1 (0.8) | 3 (4.8) | 2 (2.0) |

| 10-14–Letter loss, No. (%)d | 2 (3.3) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (1.4) | 0 | 1 (1.6) | 0 |

| ≥15-Letter loss, No. (%)d | 0 | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 104-wk Change in visual acuity letter score from baselinee | ||||||

| Median (IQR) | 13 (4 to 19) | 10 (3 to 16) | 10 (6 to 18) | 13 (6 to 20) | 14 (5 to 18) | 13 (7 to 18) |

| Mean (SD) | 12.4 (10.7) | 9.5 (10.6) | 11.7 (10.8) | 13.5 (13.0) | 11.2 (12.4) | 13.3 (10.3) |

| Change in visual acuity letter score from 24-wk visit to 104-wk visita,e | ||||||

| Median (IQR) | 2 (−3 to 7) | 2 (−5 to 5) | 4 (−1 to 7) | 1 (−3 to 6) | 2 (−3 to 6) | 1 (−3 to 5) |

| Mean (SD) | 2.5 (9.5) | 1.1 (9.3) | 3.4 (9.2) | 0.8 (8.5) | 1.4 (9.2) | 1.2 (8.9) |

| Baseline central subfield thickness, median (IQR), μm | 412 (360 to 470) | 413 (343 to 511) | 427 (363 to 506) | 365 (291 to 462) | 327 (282 to 428) | 355 (295 to 472) |

| 24-wk Central subfield thickness, median (IQR), μmf | 306 (277 to 345) | 348 (297 to 424) | 333 (280 to 398) | 213 (193 to 236) | 224 (200 to 243) | 219 (194 to 242) |

| 24-wk Change in central subfield thickness, median (IQR), μm | −94 (−149 to −65) | −49 (−106 to −6) | −87 (−133 to −23) | −143 (−251 to −74) | −102 (−198 to −48) | −133 (−242 to −68) |

| Central-involved DME, No. (%)g | 60 (100) | 118 (100) | 73 (100) | 7 (5.4) | 9 (14.5) | 12 (11.7) |

| Baseline retinal volume, median (IQR), μLh | 8.2 (7.7 to 9.9) | 8.4 (7.5 to 9.9) | 8.7 (7.8 to 10.0) | 8.4 (7.5 to 10.3) | 8.2 (7.4 to 10.5) | 9.0 (7.7 to 9.7) |

| 24-wk Retinal volume, median (IQR), μLi | 7.5 (7.1 to 8.3) | 7.9 (7.2 to 9.3) | 7.8 (7.3 to 8.8) | 7.1 (6.7 to 7.6) | 7.5 (6.8 to 8.1) | 7.2 (6.7 to 7.6) |

| 24-wk Change in retinal volume, median (IQR), μLj | −0.9 (−1.7 to −0.6) | −0.5 (−1.0 to −0.1) | −0.8 (−1.4 to −0.3) | −1.2 (−2.5 to −0.6) | −1.1 (−2.5 to −0.5) | −1.5 (−2.7 to −0.8) |

Abbreviations: DME, diabetic macular edema; IQR, interquartile range; OCT, optical coherence tomography.

24-week visual acuity unavailable for 1 eye without persistent DME, ranibizumab group.

Adjusted difference for without-with persistent DME were 3.1 (95% CI, 0.7 to 5.5; P = .01) for aflibercept; 0.7 (95% CI, −1.8 to 3.1; P = .59) for bevacizumab; and 3.7 (95% CI, 1.4 to 6.0; P = .002) for ranibizumab.

For gain ≥10 letters with vs without persistent DME, P = .02 for aflibercept, P = .65 for bevacizumab, and P = .005 for ranibizumab.

For loss ≥10 letters with vs without persistent DME, P = .10 for aflibercept, P > .99 for bevacizumab, and P = .42 for ranibizumab (Fisher exact test).

104-week visual acuity unavailable for 0, 10, and 6 eyes with persistent DME and 7, 4, and 5 eyes without persistent DME in the aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab groups, respectively.

For 1 eye in the ranibizumab group with persistent DME that completed the 24-week visit, central subfield thickness was unavailable, so the last available (20-week) central subfield thickness measurement was imputed for 24 weeks.

Central-involved DME on OCT at the visit. For Heidelberg Spectralis machines, this was defined as central subfield thickness at least 305 μm for women and at least 320 μm for men. For Zeiss Cirrus machines, this was defined as central subfield thickness at least 290 μm for women and at least 305 μm for men. For Zeiss Stratus machines, this was defined as central subfield thickness at least 250 μm for both sexes.

Baseline retinal volume was unavailable for 9, 19, and 12 eyes with persistent DME and 24, 9, and 16 eyes without persistent DME in the aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab groups, respectively.

24-week retinal volume was unavailable for 0, 2, and 1 eyes with persistent DME and 2, 2, and 1 eyes without persistent DME in the aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab groups, respectively.

24-week change in retinal volume was unavailable for 9, 21, and 13 eyes with persistent DME and 26, 10, and 16 eyes without persistent DME in the aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab groups, respectively.

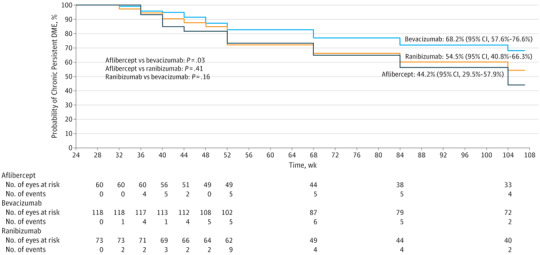

Chronic Persistent DME at 1 and 2 Years

For eyes with persistent DME through 24 weeks, Figure 2 shows the probability of chronic persistent DME within each of the 3 anti-VEGF groups during the remainder of the 2-year follow-up period. At 2 years, the cumulative probability that these eyes manifested chronic persistent DME with aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab was 44.2% (95% CI, 29.5%-57.9%), 68.2% (95% CI, 57.6%-76.6%), and 54.5% (95% CI, 40.8%-66.3%), respectively. The hazard ratios for resolution of chronic persistent DME were 1.93 (adjusted 95% CI, 1.05-3.53; P = .03) for aflibercept/bevacizumab, 1.24 (adjusted 95% CI, 0.74-2.05; P = .41) for aflibercept/ranibizumab, and 1.56 (adjusted 95% CI, 0.89-2.74; P = .16) for ranibizumab/bevacizumab. Similar trends were noted among the subgroups of eyes with better visual acuity (20/32 to 20/40, eFigure 2 in the Supplement) and worse visual acuity (20/50 to 20/320, eFigure 3 in the Supplement) at baseline.

Figure 2. Probability of Chronic Persistent Diabetic Macular Edema (DME) Through 2 Years by Treatment Group.

Eyes in which chronic persistent diabetic macular edema (DME) did not resolve by 104 weeks were censored at their last visit (n = 145), on the date of the first nonprotocol DME treatment (n = 3), or on the date of the 52-week visit if there were fewer than 4 visits in year 2 (n = 10). Two-year life-table survival estimates are shown for each group. Dark blue indicates aflibercept, bright blue indicates bevacizumab, and orange indicates ranibizumab. An event was defined as central subfield thickness less than 250 μm (Stratus equivalent) and at least 10% reduction relative to the 24-week study visit at 2 consecutive visits subsequent to the 24-week visit.

The number of injections and laser treatment sessions administered in eyes with persistent DME (through 24 weeks), stratified by the presence of chronic persistent DME at the 52-week and 104-week visits, are shown in eTable 5 in the Supplement. There were no significant differences in the median number of injections given over 2 years by presence of chronic persistent DME at 2 years. There also were no significant differences in the percentage of eyes receiving focal/grid laser by presence of chronic persistent DME at 2 years. The same outcomes stratified by baseline visual acuity are presented in eTable 6 in the Supplement (20/32 to 20/40) and eTable 7 in the Supplement (20/50 to 20/320).

Changes in visual acuity from baseline to 1 and 2 years in eyes with and without chronic persistent DME (among those with persistent DME through 24 weeks) by treatment group are shown in Table 2. At 2 years, the adjusted difference in mean change in visual acuity between eyes without and with persistent DME was −4.3 (95% CI, −8.8 to 0.2; P = .06) for aflibercept, −0.3 (95% CI, −3.9 to 3.3; P = .87) for bevacizumab, and 4.7 (95% CI, 0.1 to 9.3; P = .05) for ranibizumab. The percentage of eyes gaining 10 or more letters from baseline at 2 years was not significantly different in eyes with vs without chronic persistent DME at 2 years (aflibercept, 62.1% [18 of 29] vs 63.3% [19 of 30]; P = .88; bevacizumab, 51.4% [36 of 70] vs 54.8% [17 of 31]; P = .96; and ranibizumab, 44.7% [17 of 38] vs 65.5% [19 of 29]; P = .10). Overall, only 3 eyes with chronic persistent DME and 2 eyes without chronic persistent DME lost at least 10 letters (≤3.3% in each treatment by persistent DME subgroup) with no definitive differences identified within each treatment group (P > .99 for all groups). Similar results were found when stratifying by baseline visual acuity (eTable 8 in the Supplement [20/32 to 20/40] and eTable 9 in the Supplement, [20/50 to 20/320]).

Table 2. Visual Acuity and OCT Outcomes by Presence of Chronic Persistent Diabetic Macular Edema.

| Characteristic | Eyes With Chronic Persistent DME | Eyes Without Chronic Persistent DME | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aflibercept (n = 47) |

Bevacizumab (n = 98) |

Ranibizumab (n = 59) |

Aflibercept (n = 13) |

Bevacizumab (n = 20) |

Ranibizumab (n = 14) |

|

| 52-wk Visita | ||||||

| Baseline visual acuity, median (IQR) | ||||||

| Letter score | 69 (75 to 59) | 69 (73 to 59) | 68 (73 to 63) | 65 (72 to 60) | 69 (74 to 57) | 70 (74 to 64) |

| Approximate Snellen equivalent | 20/40 (20/32 to 20/63) | 20/40 (20/40 to 20/63) | 20/50 (20/40 to 20/63) | 20/50 (20/40 to 20/63) | 20/40 (20/40 to 20/80) | 20/40 (20/32 to 20/50) |

| Follow-up visual acuity, median (IQR) | ||||||

| Letter score | 79 (85 to 73) | 77 (82 to 68) | 77 (84 to 67) | 79 (83 to 75) | 79 (85 to 73) | 83 (84 to 81) |

| Approximate Snellen equivalent | 20/25 (20/20 to 20/40) | 20/32 (20/25 to 20/50) | 20/32 (20/20 to 20/50) | 20/25 (20/25 to 20/32) | 20/25 (20/20 to 20/40) | 20/25 (20/20 to 20/25) |

| 20/25 or Better, No. (%) | 24 (51.1) | 42 (42.9) | 26 (44.1) | 7 (53.8) | 10 (50.0) | 11 (78.6) |

| 20/32 to 20/40, No. (%) | 14 (29.8) | 30 (30.6) | 18 (30.5) | 5 (38.5) | 7 (35.0) | 2 (14.3) |

| 20/50 to 20/80, No. (%) | 8 (17.0) | 18 (18.4) | 10 (16.9) | 1 (7.7) | 2 (10.0) | 1 (7.1) |

| 20/100 to 20/160, No. (%) | 1 (2.1) | 4 (4.1) | 4 (6.8) | 0 | 1 (5.0) | 0 |

| 20/200 or Worse, No. (%) | 0 | 4 (4.1) | 1 (1.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Change in visual acuity letter score | ||||||

| Median (IQR) | 10 (7 to 17) | 8 (2 to 14) | 9 (3 to 13) | 13 (11 to 18) | 12 (9 to 17) | 13 (6 to 18) |

| Mean (SD)b | 11.9 (10.3) | 8.4 (10.2) | 8.5 (10.2) | 13.9 (5.5) | 11.7 (7.5) | 12.6 (7.5) |

| ≥15-Letter gain, No. (%) | 18 (38.3) | 24 (24.5) | 13 (22.0) | 4 (30.8) | 8 (40.0) | 5 (35.7) |

| 10-14–Letter gain, No. (%) | 7 (14.9) | 22 (22.4) | 13 (22.0) | 7 (53.8) | 6 (30.0) | 4 (28.6) |

| 5-9–Letter gain, No. (%) | 12 (25.5) | 19 (19.4) | 15 (25.4) | 1 (7.7) | 4 (20.0) | 3 (21.4) |

| Within 4 letters, No. (%) | 7 (14.9) | 23 (23.5) | 15 (25.4) | 1 (7.7) | 0 | 2 (14.3) |

| 5-9–Letter loss, No. (%) | 1 (2.1) | 6 (6.1) | 1 (1.7) | 0 | 2 (10.0) | 0 |

| 10-14–Letter loss, No. (%) | 2 (4.3) | 2 (2.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ≥15-Letter loss, No. (%) | 0 | 2 (2.0) | 2 (3.4) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Central-involved DME, No. (%)c | 39 (83.0) | 94 (95.9) | 51 (86.4) | 0 | 8 (40.0) | 1 (7.1) |

| 104-wk Visitd | Aflibercept (n = 29) |

Bevacizumab (n = 70) |

Ranibizumab (n = 38) |

Aflibercept (n = 30) |

Bevacizumab (n = 31) |

Ranibizumab (n = 29) |

| Baseline visual acuity, median (IQR) | ||||||

| Letter score | 69 (74 to 59) | 70 (73 to 62) | 71 (73 to 65) | 67 (75 to 63) | 68 (73 to 60) | 68 (73 to 62) |

| Approximate Snellen equivalent | 20/40 (20/32 to 20/63) | 20/40 (20/40 to 20/63) | 20/40 (20/40 to 20/50) | 20/50 (20/32 to 20/63) | 20/50 (20/40 to 20/63) | 20/50 (20/40 to 20/63) |

| Follow-up visual acuity, median (IQR) | ||||||

| Letter score | 80 (87 to 77) | 78 (82 to 72) | 79 (84 to 70) | 78 (85 to 72) | 76 (83 to 71) | 81 (86 to 76) |

| Approximate Snellen equivalent | 20/25 (20/20 to 20/32) | 20/32 (20/25 to 20/40) | 20/32 (20/20 to 20/40) | 20/32 (20/20 to 20/40) | 20/32 (20/25 to 20/40) | 20/25 (20/20 to 20/32) |

| 20/25 or Better, No. (%) | 18 (62.1) | 34 (48.6) | 19 (50.0) | 13 (43.3) | 11 (35.5) | 20 (69.0) |

| 20/32 to 20/40, No. (%) | 9 (31.0) | 26 (37.1) | 10 (26.3) | 13 (43.3) | 16 (51.6) | 6 (20.7) |

| 20/50 to 20/80, No. (%) | 2 (6.9) | 8 (11.4) | 5 (13.2) | 2 (6.7) | 3 (9.7) | 3 (10.3) |

| 20/100 to 20/160, No. (%) | 0 | 1 (1.4) | 4 (10.5) | 2 (6.7) | 1 (3.2) | 0 |

| 20/200 or Worse, No. (%) | 0 | 1 (1.4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Change in visual acuity letter score | ||||||

| Median (IQR) | 15 (5 to 21) | 10 (3 to 17) | 9 (5 to 14) | 12 (4 to 14) | 10 (4 to 16) | 13 (8 to 22) |

| Mean (SD)e | 14.8 (12.1) | 10.3 (9.6) | 9.3 (11.7) | 10.2 (8.9) | 10.7 (10.0) | 14.7 (8.7) |

| ≥15-Letter gain, No. (%)f | 15 (51.7) | 23 (32.9) | 9 (23.7) | 7 (23.3) | 9 (29.0) | 12 (41.4) |

| 10-14–Letter gain, No. (%)f | 3 (10.3) | 13 (18.6) | 8 (21.1) | 12 (40.0) | 8 (25.8) | 7 (24.1) |

| 5-9–Letter gain, No. (%) | 4 (13.8) | 14 (20.0) | 12 (31.6) | 2 (6.7) | 5 (16.1) | 9 (31.0) |

| Within ±4 letters, No. (%) | 6 (20.7) | 16 (22.9) | 6 (15.8) | 8 (26.7) | 6 (19.4) | 1 (3.4) |

| 5-9–Letter loss, No. (%) | 1 (3.4) | 2 (2.9) | 2 (5.3) | 0 | 2 (6.5) | 0 |

| 10-14–Letter loss, No. (%)g | 0 | 2 (2.9) | 0 | 1 (3.3) | 1 (3.2) | 0 |

| ≥15-Letter loss, No. (%)g | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Central-involved DME, No. (%)c | 25 (86.2) | 64 (91.4) | 33 (89.2) | 2 (6.7) | 11 (35.5) | 5 (17.2) |

Abbreviations: DME, diabetic macular edema; IQR, interquartile range, OCT, optical coherence tomography.

Includes eyes completing the 52-week visit with DME on OCT at baseline, persistent DME through 24 weeks, 4 injections prior to 24 weeks (or success after 3 injections), 5 of 7 visits completed between weeks 28 and 52, and no nonprotocol DME treatment prior to 52 weeks.

Adjusted difference for without-with chronic persistent DME were 1.3 (95% CI, −3.5 to 6.0, P = .59) for aflibercept; 3.3 (95% CI, −1.5 to 8.0; P = .17) for bevacizumab; and 5.1 (95% CI, −0.5 to 10.7; P = .07) for ranibizumab.

Central-involved DME on OCT at the visit. For Heidelberg Spectralis machines, this was defined as central subfield thickness at least 305 μm for women and at least 320 μm for men. For Zeiss Cirrus machines, this was defined as central subfield thickness at least 290 μm for women and at least 305 μm for men. For Zeiss Stratus machines, this was defined as central subfield thickness at least 250 μm for both sexes. One hundred four–week central subfield thickness unavailable for 1 eye in the ranibizumab group with chronic persistent DME.

Includes eyes completing the 104-week visit with DME on OCT at baseline, persistent DME through 24 weeks, 4 injections prior to 24 weeks (or success after 3 injections), 5 of 7 visits completed between weeks 28 and 52, at least 4 visits completed in year 2, and no nonprotocol DME treatment prior to 104 weeks

Adjusted difference for without-with chronic persistent DME was −4.3 (95% CI, −8.8 to 0.2; P = .06) for aflibercept; −0.3 (95% CI, −3.9 to 3.3; P = .87) for bevacizumab; and 4.7 (95% CI, 0.1 to 9.3, .05) for ranibizumab.

For gain ≥10 letters with vs without chronic persistent DME, P = .88 for aflibercept; P = .96 for bevacizumab; and P = .10 for ranibizumab.

For loss ≥10 letters with vs without chronic persistent DME, P > .99 for aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab.

Discussion

These data from Protocol T suggest that, in a group of eyes treated with anti-VEGF for DME, there is continued resolution of DME on optical coherence tomography in an increasing number of eyes from week 12 through week 24 with continued monthly injections, particularly with aflibercept and ranibizumab. Therefore, caution should be exercised when considering switching therapies for DME if there is a limited response following 3 or more initial anti-VEGF injections.7 These data show that by remaining on the DRCR.net retreatment algorithm for DME, many eyes will have resolution of DME with additional injections at weeks 12, 16, and 20. Furthermore, these data suggest meaningful gains in visual acuity from baseline and a low risk of vision loss across all 3 anti-VEGF agents, even if DME chronically persists through 2 years. The DRCR.net retreatment algorithm allows for deferral of injections, even in the presence of persistent DME, after the first 24 weeks of injections, provided there has not been improvement or worsening of visual acuity (≥5 letters) or CST (≥10%) at 2 consecutive visits. The only adjuvant or alternative therapy permitted in the absence of substantial visual acuity loss was focal/grid laser, which was added to thickened areas in the macula, warranting treatment per protocol at or after 24 weeks if CST was at least 250 μm (Stratus equivalent) and if vision and CST were stable despite injections for 2 consecutive visits.

A question that remains is whether switching eyes with persistent DME to alternative therapies other than focal/grid laser after 3 or at least 6 injections would improve on the outcomes reported here in eyes that were not given alternative therapies. To determine the true effect of adding or switching therapies compared with the current DRCR.net treatment regimen for DME, it is essential to have a control arm in which the treatment does not change,8 as in the results presented in this post hoc analysis. As an example where an alternative therapy was not shown to be beneficial, in the DRCR.net Protocol U, ranibizumab with or without addition of sustained release dexamethasone implant (Ozurdex) was compared among eyes that had persistent DME despite at least 3 prior anti-VEGF injections before enrollment and 3 additional ranibizumab injections during a 12-week run-in phase. There was no significant difference between the groups for the primary outcome of change in visual acuity from baseline to 24 weeks.9

Importantly, almost no eyes with chronic persistent DME lost substantial visual acuity (≥2 lines [≥10 letters]) from baseline at 2 years (≤3.3% in each treatment by chronic persistent DME subgroup), while a gain of at least 2 lines from baseline at 2 years was achieved in 62.1%, 51.4%, and 44.7% of aflibercept-treated, bevacizumab-treated, and ranibizumab-treated eyes with chronic persistent DME, respectively. These outcomes were in the setting of no definitive differences identified between eyes with and without chronic persistent DME in the number of injections given or the percentage of eyes receiving focal/grid laser through 2 years. It is unknown what effect continuing intravitrous anti-VEGF injections after eyes were stable for 2 consecutive visits beyond the 6-month visit may have had on outcomes presented here.

For eyes with persistent DME through 24 weeks, there were no definitive differences identified in visual acuity change from baseline at 2 years between eyes with and without chronic persistent DME in the aflibercept or bevacizumab groups. However, for the ranibizumab group, vision outcomes were slightly worse among eyes with chronic persistent DME, as was seen in Protocol I at 3 years.2 There also were several additional findings in this study that were similar to findings from Protocol I, which is not surprising given the similar cohorts and retreatment algorithms.2 First, the percentage of ranibizumab-treated eyes with persistent DME through 24 weeks was 39.5% in Protocol I vs 41.5% in Protocol T. Second, persistent DME through 24 weeks appeared to be associated with greater baseline CST (median 415 μm with persistent DME vs 353 μm, combining groups in Protocol T), as was found in Protocol I. Finally, the 54.5% rate of chronic persistent DME at 2 years among those with persistent DME through 24 weeks seen in the ranibizumab group in Protocol T is comparable with the rate of 55.8% in Protocol I.2

Limitations

One limitation of this study is that the primary comparisons are based on groups determined by response to treatment, which is not a randomized comparison. Another limitation is the reduction in sample size and statistical precision as a result of limiting many analyses to eyes in which DME persisted for 24 weeks. Nevertheless, bias should have been minimized because retention was more than 90%,10 visual acuity testers were masked at annual visits, and objective OCT data were used in the retreatment algorithm. Also, many outcomes were compared between and within 3 treatment groups, reducing the confidence one may place in any particular finding and increasing the possibility that some results could be owing to chance, even with the multiplicity adjustments undertaken.

There is possible selection bias in comparing eyes with persistent DME through 24 weeks by treatment group. For example, eyes that have persistent DME after 6 aflibercept injections may not be comparable with eyes with persistent DME after 6 bevacizumab injections because the eyes not responding to aflibercept may be more resistant to treatment than those not responding to bevacizumab. However, this bias would be in the opposite direction of the observed finding that resolution of chronic persistent DME through 2 years is more likely with aflibercept than bevacizumab. There is also a large treatment group imbalance in sample size in the 24-week cohort, making comparisons involving bevacizumab, such as the proportion with resolution of persistent DME over time, more likely to have lower P values than similar proportions with aflibercept because the bevacizumab group had approximately double the sample size of the other 2 groups.

Conclusions

The results presented here show that aflibercept and ranibizumab are more effective than bevacizumab in preventing persistent DME through 24 weeks and that eyes with persistent DME through 24 weeks are more likely to subsequently achieve resolution of DME by 2 years with aflibercept than bevacizumab. When following the retreatment protocol used in this trial of eyes with DME and vision impairment, improvement from baseline in visual acuity is the norm, and substantial loss of visual acuity (≥2 lines) is uncommon across all 3 anti-VEGF agents, even when DME chronically persists through 2 years. These observations were made while withholding continued anti-VEGF injections as early as 6 months for stable, persistent DME in many eyes, placing adjuvant focal/grid laser when indicated per protocol, and without administering other alternative therapies such as corticosteroids. These analyses are consistent with and strengthen similar conclusions from earlier analyses of Protocol I.2

eFigure 1. Flowchart of Study Eyes Included in Analyses

eFigure 2. Probability of Chronic Persistent Diabetic Macular Edema Through 2 Years by Treatment Group Among Eyes With Baseline Visual Acuity Letter Score of 78 to 69 (Approximate Snellen Equivalent 20/32 to 20/40)

eFigure 3. Probability of Chronic Persistent Diabetic Macular Edema Through 2 Years by Treatment Group Among Eyes With Baseline Visual Acuity Letter Score of 68 to 24 (Approximate Snellen Equivalent 20/50 to 20/320)

eTable 1. Persistent Diabetic Macular Edema Through 24 Weeks Stratified by Baseline Visual Acuity

eTable 2. Baseline Participant and Ocular Characteristics by Presence of Persistent Diabetic Macular Edema Through 24 Weeks

eTable 3. Visual Acuity and Optical Coherence Tomography Outcomes at 24 Weeks by Presence of Persistent Diabetic Macular Edema Among Eyes With Baseline Visual Acuity Letter Score of 78 to 69 (Approximate Snellen Equivalent 20/32 to 20/40)

eTable 4. Visual Acuity and Optical Coherence Tomography Outcomes at 24 Weeks by Presence of Persistent Diabetic Macular Edema Among Eyes With Baseline Visual Acuity Letter Score of 68 to 24 (Approximate Snellen Equivalent 20/50 to 20/320)

eTable 5. Injections and Laser Treatment by Presence of Chronic Persistent Diabetic Macular Edema

eTable 6. Injections and Laser Treatment by Presence of Chronic Persistent Diabetic Macular Edema Among Eyes With Baseline Visual Acuity Letter Score 78 to 69 (Approximate Snellen Equivalent 20/32 to 20/40)

eTable 7. Injections and Laser Treatment by Presence of Chronic Persistent Diabetic Macular Edema Among Eyes With Baseline Visual Acuity Letter Score 68 to 24 (Approximate Snellen Equivalent 20/50 to 20/320)

eTable 8. Visual Acuity and Optical Coherence Tomography Outcomes by Presence of Chronic Persistent Diabetic Macular Edema Among Eyes With Baseline Visual Acuity Letter Score 78 to 69 (Approximate Snellen Equivalent 20/32 to 20/40)

eTable 9. Visual Acuity and OCT Outcomes by Presence of Chronic Persistent Diabetic Macular Edema Among Eyes With Baseline Visual Acuity Letter Score 68 to 24 (Approximate Snellen Equivalent 20/50 to 20/320)

References

- 1.Solomon SD, Chew E, Duh EJ, et al. Diabetic retinopathy: a position statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(3):412-418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bressler SB, Ayala AR, Bressler NM, et al. ; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network . Persistent macular thickening after ranibizumab treatment for diabetic macular edema with vision impairment. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134(3):278-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elman MJ, Aiello LP, Beck RW, et al. ; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network . Randomized trial evaluating ranibizumab plus prompt or deferred laser or triamcinolone plus prompt laser for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(6):1064-1077.e35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wells JA, Glassman AR, Ayala AR, et al. ; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network . Aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(13):1193-1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beck RW, Moke PS, Turpin AH, et al. A computerized method of visual acuity testing: adaptation of the early treatment of diabetic retinopathy study testing protocol. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135(2):194-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hochberg Y. A sharper Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika. 1988;75(4):800-802. doi: 10.1093/biomet/75.4.800 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzalez VH, Campbell J, Holekamp NM, et al. Early and long-term responses to anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy in diabetic macular edema: analysis of Protocol I data. Am J Ophthalmol. 2016;172:72-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferris FL III, Maguire MG, Glassman AR, Ying G-s, Martin DF. Evaluating effects of switching anti–vascular endothelial growth factor drugs for age-related macular degeneration and diabetic macular edema. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135(2):145-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maturi RK, Glassman AR, Liu D. Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network. Effect of adding dexamethasone to continued ranibizumab treatment in patients with persistent diabetic macular edema: a DRCR Network phase 2 randomized clinical trial [published online November 11, 2017. JAMA Ophthalmol. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.4914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wells JA, Glassman AR, Ayala AR, et al. ; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network . Aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema: two-year results from a comparative effectiveness randomized clinical trial. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(6):1351-1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Flowchart of Study Eyes Included in Analyses

eFigure 2. Probability of Chronic Persistent Diabetic Macular Edema Through 2 Years by Treatment Group Among Eyes With Baseline Visual Acuity Letter Score of 78 to 69 (Approximate Snellen Equivalent 20/32 to 20/40)

eFigure 3. Probability of Chronic Persistent Diabetic Macular Edema Through 2 Years by Treatment Group Among Eyes With Baseline Visual Acuity Letter Score of 68 to 24 (Approximate Snellen Equivalent 20/50 to 20/320)

eTable 1. Persistent Diabetic Macular Edema Through 24 Weeks Stratified by Baseline Visual Acuity

eTable 2. Baseline Participant and Ocular Characteristics by Presence of Persistent Diabetic Macular Edema Through 24 Weeks

eTable 3. Visual Acuity and Optical Coherence Tomography Outcomes at 24 Weeks by Presence of Persistent Diabetic Macular Edema Among Eyes With Baseline Visual Acuity Letter Score of 78 to 69 (Approximate Snellen Equivalent 20/32 to 20/40)

eTable 4. Visual Acuity and Optical Coherence Tomography Outcomes at 24 Weeks by Presence of Persistent Diabetic Macular Edema Among Eyes With Baseline Visual Acuity Letter Score of 68 to 24 (Approximate Snellen Equivalent 20/50 to 20/320)

eTable 5. Injections and Laser Treatment by Presence of Chronic Persistent Diabetic Macular Edema

eTable 6. Injections and Laser Treatment by Presence of Chronic Persistent Diabetic Macular Edema Among Eyes With Baseline Visual Acuity Letter Score 78 to 69 (Approximate Snellen Equivalent 20/32 to 20/40)

eTable 7. Injections and Laser Treatment by Presence of Chronic Persistent Diabetic Macular Edema Among Eyes With Baseline Visual Acuity Letter Score 68 to 24 (Approximate Snellen Equivalent 20/50 to 20/320)

eTable 8. Visual Acuity and Optical Coherence Tomography Outcomes by Presence of Chronic Persistent Diabetic Macular Edema Among Eyes With Baseline Visual Acuity Letter Score 78 to 69 (Approximate Snellen Equivalent 20/32 to 20/40)

eTable 9. Visual Acuity and OCT Outcomes by Presence of Chronic Persistent Diabetic Macular Edema Among Eyes With Baseline Visual Acuity Letter Score 68 to 24 (Approximate Snellen Equivalent 20/50 to 20/320)