Abstract

In light of initiatives to decrease use of unnecessary services, this article examines whether current guidelines for diabetes and cardiovascular disease preferentially recommend intensification rather than deintensification of care.

By shaping physician behavior and performance measures, clinical practice guidelines could help or hinder efforts to balance overuse and underuse. This is especially critical for chronic conditions such as diabetes or cardiovascular disease, in which management must be continuously reevaluated as patient health, treatment goals, and medical knowledge evolve. While initiatives to decrease use of unnecessary services such as Choosing Wisely largely address 1-time services (eg, antibiotics for upper respiratory tract infections),1 most care involves ongoing testing or treatment decisions for chronic disease. Guidelines should therefore specify when to deintensify care—stopping or scaling back the intensity or frequency of routine services.2 To better understand the balance between overuse and underuse in current guidelines, we examined whether guidelines in 2 major clinical areas with well-developed guidelines preferentially recommend intensification rather than deintensification.

Methods

We identified all current guidelines for diabetes and cardiovascular disease (n = 22) released from January 1, 2012, through April 30, 2016, by 7 major guideline developers representing federal organizations or professional societies and meeting the plurality of standards set by the National Academy of Medicine.3 We included services provided in the ambulatory setting, to the same patient over time, and under a primary care physician’s discretion. We excluded pediatric, palliative, perioperative, or prenatal services.

One coder (A.A.M., W.F., or David E. Goodrich) abstracted and provisionally categorized each recommendation as intensification or deintensification (Box) using prespecified rules and tabulated across (1) guideline developers, (2) clinical services, and (3) evidence strength. At least 2 physician coders (T.P.H., T.J.C., J.B.S., E.A.K.) reviewed all recommendations for final determination of deintensification status.

Box. Examples of Clinical Practice Guideline Recommendations for Intensification and Deintensification of Routine Medical Services.

Intensification Recommendations: Medical Services Should Be Continued or Delivered More Frequently or at a Higher Intensity

People with diabetes and hypertension should be treated to a systolic blood pressure goal of less than 140 mm Hg.a

Perform the hemoglobin A1C test at least two times a year in patients who are meeting treatment goals (and who have stable glycemic control).a

Deintensification Recommendations: Medical Services Should Be Discontinued or Delivered Less Frequently or at a Lower Intensity

There is potential harm in lowering systolic blood pressure to less than 120 mm Hg in older adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus.b

There is potential harm in lowering (target goal) hemoglobin A1c to less than 6.5% in older adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus.b

Results

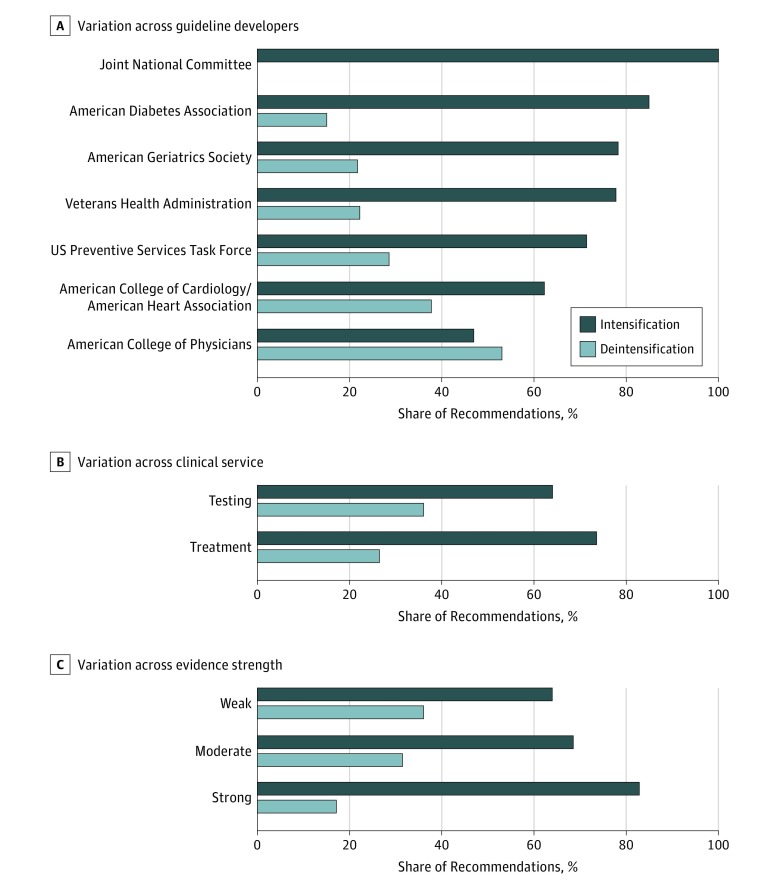

Of 361 recommendations, we categorized 256 (71%) as intensification and 105 (29%) as deintensification. We identified large variability in how frequently guideline developers provided deintensification recommendations (range, 0%-53%; χ2 P = .004) (Figure). Deintensification did not vary significantly across testing vs treatment recommendations (36 of 100 [36%] vs 69 of 261 [26%]; χ2 P = .07) (Figure, B). Of recommendations backed by strong evidence, only 17% (17 of 99) addressed deintensification vs 83% (82 of 99) that addressed intensification (χ2 P = .007) (Figure, C).

Figure. Variation in the Share of Intensification vs Deintensification Recommendations.

Guidelines for cardiovascular disease management included ischemic heart disease, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, acute coronary syndrome, myocardial infarction, and cognitive or mental health sequelae. The evidence strength of the recommendations was based on the evidence ratings provided by the guideline developers. Recommendations were drawn from the following guidelines (N = 22 total guidelines). American Diabetes Association (n = 1): Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2016 (2016). Eighth Joint National Committee (n = 1): Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. American Geriatrics Society (n = 1): Improving the Care of Older Adults With Diabetes Mellitus: 2013 Update (2013). Veterans Health Administration (n = 2): Diagnosis and Management of Hypertension in the Primary Care Setting (2014); Management of Dyslipidemia for Cardiovascular Risk Reduction (2014). US Preventive Services Task Force (n = 6): Screening for Coronary Heart Disease With Electrocardiography (2012); Vitamin, Mineral, and Multivitamin Supplements for the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease and Cancer (2014); Screening for High Blood Pressure in Adults (2015); Screening for Abnormal Blood Glucose and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (2015); Aspirin Use to Prevent Cardiovascular Disease and Colorectal Cancer (2015; draft); Statin Use for the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Adults: Preventive Medication (2015; draft). American College of Cardiologists/American Heart Association (n = 9): Secondary Prevention and Risk Reduction Therapy for Patients With Coronary and Other Atherosclerotic Vascular Disease (2011); Effectiveness-Based Guidelines for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Women (2011); Diagnosis and Management of Patients With Stable Ischemic Heart Disease (2012; jointly issued with the American College of Physicians); Assessment of Cardiovascular Risk (2013); Treatment of Blood Cholesterol to Reduce Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Risk in Adults (2013); Management of Heart Failure (2013); Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation (2014); Management of Adult Patients With Supraventricular Tachycardia (2015; only for the recommendations related to atrial fibrillation); Duration of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease (2016). American College of Physicians (n = 3): Diagnosis and Management of Patients With Stable Ischemic Heart Disease (2012; jointly issued with the American College of Cardiologists/American Heart Association); Oral Pharmacologic Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (2012); Cardiac Screening With Electrocardiography, Stress Echocardiography, or Myocardial Perfusion Imaging (2015).

Discussion

Current guidelines for diabetes and cardiovascular disease management provide substantially more recommendations for intensification than deintensification of routine services. In addition, we found considerable variation in how frequently guideline developers recommend deintensification.

Why do most guidelines offer so little guidance on deintensifying care? One explanation is that there is simply more evidence regarding intensification. Randomized clinical trials, the underlying source for most guidelines, focus on generating evidence for initiating or intensifying treatment. Our finding that most “strong evidence” recommendations pertain to intensification supports this. However, even among recommendations based on weak data, a majority focus on intensification.

The large variation detected across guideline developers underscores a second explanation—developers’ inconsistent engagement with existing evidence on benefit and harm. This reflects the widespread predilection for generalizing benefits observed in homogenous trial populations to broader populations4 and is exacerbated by developers’ tendency to provide clear, unqualified intensification recommendations (eg, “People with diabetes and hypertension should be treated to a systolic blood pressure goal of <140 mm Hg”) while obscuring deintensification recommendations with vague or cautionary statements (eg, “Glycemic goals for some older adults might reasonably be relaxed, using individual criteria, but hyperglycemia…should be avoided”). Performance measures reflect and reinforce this inattention, rarely addressing overuse and focusing instead on intensifying care to achieve a target (eg, hemoglobin A1c <8% [to convert to proportion of total hemoglobin, multiply by 0.01]).5,6

Given guidelines’ potential impact on clinical practice and performance measurement, appropriate attention to deintensification is critical. Although deintensification trials would be ideal, existing trials should document harm in a more reliable manner suitable for capturing adverse events and changing patient circumstances. When extrapolating treatment effects from trials to target populations, guideline developers should use weighting schemes that account for treatment heterogeneity and can be adapted to incorporate patient preferences and enable shared decision making.4 Where clinical data are sparse, developers should demonstrate equal restraint in recommending intensification vs deintensification. And where evidence for harm is strong, developers should provide specific guidance in the form of clear recommendations, algorithms, and decision support tools on when, how, and for whom to stop or scale back care.

Footnotes

Source: American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2016; pages s40 and s60.

Source: American Geriatrics Society Guidelines for Improving the Care of Older Adults with Diabetes Mellitus: 2013 Update; page 2021.

References

- 1.Morden NE, Colla CH, Sequist TD, Rosenthal MB. Choosing Wisely—the politics and economics of labeling low-value services. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(7):589-592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kerr EA, Hofer TP. Deintensification of routine medical services: the next frontier for improving care quality. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(7):978-980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Academy of Sciences Institute of Medicine: Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. National Academies Press; 2011. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2011/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines-We-Can-Trust.aspx. Accessed April 1, 2017.

- 4.Kent DM, Hayward RA. Limitations of applying summary results of clinical trials to individual patients: the need for risk stratification. JAMA. 2007;298(10):1209-1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newton EH, Zazzera EA, Van Moorsel G, Sirovich BE. Undermeasuring overuse—an examination of national clinical performance measures. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(10):1709-1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez-Gutierrez R, Ospina NS, McCoy RG, Lipska KJ, Shah ND, Montori VM; Hypoglycemia as a Quality Measure in Diabetes Study Group . Inclusion of hypoglycemia in clinical practice guidelines and performance measures in the care of patients with diabetes. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(11):1714-1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]