Abstract

This data analysis examines the differences in industry payments to male and female physicians in 2015.

Although the number of women in medicine in the United States has increased (34% of active physicians in 2015; 47% of enrolled medical students in 2015-2016), inequities between men and women physicians are pervasive. Most physician specialties are predominantly male. Compared with men, women physicians receive lower salaries and less research funding. Career progression is hindered by the proverbial “glass ceiling,” with fewer women in faculty, department head, and dean positions.

In our recent study on industry payments to physicians, we found that men received a greater number and higher value of general payments than women physicians and were more likely to hold ownership interests and receive royalty or licensing payments when grouped by specialty type (surgeons, primary care, specialists, and interventionalists). We extended this study of the types and distributions of payments from industry to physicians in 2015 to provide greater detail on the impact of sex within each specialty.

Methods

We analyzed all physicians in the 2015 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services National Plan & Provider Enumeration System (NPPES) database linked to 2015 Open Payment reports of industry payments (general payments and ownership interests) to US allopathic and osteopathic physicians. General payments include all forms of payment (such as speaking fees or food and beverage) other than those classified for research purposes. Data were aggregated by specialty, and payment outcomes were compared between physician sexes. Further details of the methods were previously described. As years in practice is not included in Open Payments or NPPES, we also conducted a subset analysis of all licensed practitioners in California to investigate years in practice as a potential confounder. This study was approved by the University of California San Diego institutional review board.

Results

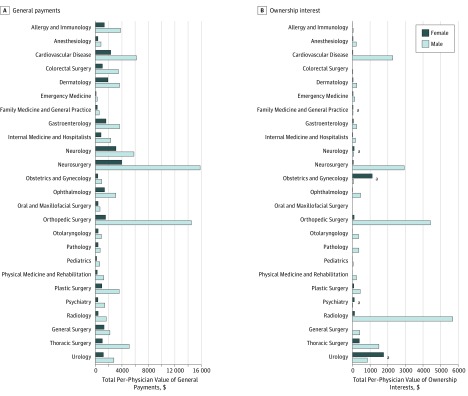

Across all specialties, men received a higher per-physician value of general payments than women, with a median difference of $1470 (Figure, A). The largest mean difference ($12 976) was for orthopedic surgeons. The largest per-physician value of general payments for men was for neurosurgery ($15 821 compared with $3970 for women neurosurgeons). Men held 93% of the value received from ownership interests and received a higher per-physician value across most specialties, with the largest difference among radiologists ($5568; Figure, B). Women in certain fields, such as obstetrics and gynecology, psychiatry, and urology, held higher values of ownership interests than men, with the greatest difference in obstetrics and gynecology ($1061). After controlling for years in practice among 63 466 California physicians, men were more likely than women to receive general payments and hold ownership interests and received higher numbers and values of general payments (Table).

Figure. Total Per-Physician Value by Sex Across All Medical Specialties.

A, Total per-physician value of general payments by physician sex across all medical specialties. General payments include payments from service fees, charity, speaker fees, consulting fees, ownership interests, education, entertainment, food and beverage, gifts, grants, and honoraria. B, Total per-physician value of ownership interests by physician sex across all medical specialties. Ownership interests include stocks or stock options, partnership shares, limited liability company membership, bonds, or other financial instruments secured by the reporting entity that were held by physicians. Excluded from ownership interest were payments received as compensation (until exercised), as part of a retirement plan, or interest in a publicly traded security or mutual fund.

aIndicates women physicians received a higher per-physician value of ownership interests compared with men physicians within that specialty.

Table. Industry Payments to Men vs Women California Physicians in Each Specialty Group Adjusted for Years in Practicea.

| Payment | Relative Likelihood of Men vs Women Physicians by Specialty Group, OR (95% CI)b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men Surgeons | Men Primary Care | Men Specialists | Men Interventionalists | |

| General payment receipt | 1.47 (1.35-1.59) | 1.62 (1.54-1.70) | 1.12 (1.04-1.21) | 2.39 (2.10-2.72) |

| Ownership interest receipt | 15.59 (4.96-49.03) | 2.68 (1.10-6.52) | 3.61 (1.09-11.92) | ∞c |

| No. of general payments | 1.37 (1.28-1.47) | 1.39 (1.29-1.50) | 1.63 (1.56-1.72) | 1.88 (1.66-2.12) |

| Value of general payments (% difference) | 12 (10-14) | 12 (11-13) | 4 (5-6) | 14 (11-17) |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; ND, no data.

Relative likelihood of men physicians receiving payments compared with women physicians within each specialty group (odds ratio [OR]), as well as relative number of payments and percent difference of the value of payments between men and women within each specialty group (incident rate ratio [IRR] and percent difference, respectively). This multivariable analysis also adjusts for physician sex, specialty group, practice spending region, sole proprietorship, years of practice, and the interaction between physician sex and specialty.

Reference group for each outcome is women physicians within each specialty group.

There is an infinite OR for ownership interests among men interventionalists given 0 women interventionalists of the matched sample from California received ownership interests.

Discussion

Across most specialties in 2015, we found that men physicians in the United States received higher values of general payments from industry and held higher values of ownership interests than women physicians. In a subset analysis of California physicians controlling for years in practice, this pattern persisted.

Two of many possible explanations are that women physicians are less focused on industry endeavors and may have different career motivations. Recent data on US dual-physician couples showed that women physicians with children worked fewer hours than women without children, whereas men physicians’ career hours were not as affected by parenting obligations. Women may negotiate less often for payments, or perhaps biomedical companies offer women physicians payments of lower value. Biomedical industries, largely led by men, may target more men physicians for product development or ownership. In our analysis, women physicians also earned significantly less in royalty payments (data not shown); other studies have shown that women hold fewer patents than their male counterparts, and women who obtain patents are less likely to license them.

Limitations of our study include the inability to account for certain potential confounders not included in NPPES, such as age or race/ethnicity. In addition, our study was retrospective; we were unable to examine cause-and-effect and other potential relationships between industry payments and physician behavior.

References

- 1.Association of American Medical Colleges Total U.S. Medical School Enrollment by Race/Ethnicity and Sex, 2013-2014 through 2016-2017. https://www.aamc.org/download/321534/data/factstableb3.pdf. Accessed October 23, 2017.

- 2.Ash AS, Carr PL, Goldstein R, Friedman RH. Compensation and advancement of women in academic medicine: is there equity? Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(3):205-212. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tringale KR, Marshall D, Mackey TK, Connor M, Murphy JD, Hattangadi-Gluth JA. Types and distribution of payments from industry to physicians in 2015. JAMA. 2017;317(17):1774-1784. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.3091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Medical Board of California Physicians and Surgeons. http://www.mbc.ca.gov/Licensees/Physicians_and_Surgeons/. Accessed November 14, 2016.

- 5.Ly DP, Seabury SA, Jena AB. Hours worked among US dual physician couples with children, 2000 to 2015. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(10):1524-1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sugimoto CR, Ni C, West JD, Larivière V. The academic advantage: gender disparities in patenting. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0128000. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]