This study investigates the incidence and prognosis of gastrinomas originating in the hepatobiliary tract in patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome.

Key Points

Question

Do primary gastrinomas of the liver exist?

Findings

In this series of 223 patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, primary gastrinomas of the liver were the second most common extrapancreatic, extraintestinal site for a primary gastrinoma and may metastasize to regional lymph nodes. Aggressive resection is indicated because cure rates and survival are similar to those for primary gastrinomas in other locations.

Meaning

Liver primary gastrinomas occur and warrant aggressive resection including regional lymph nodes.

Abstract

Importance

Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (ZES) is a life-threatening disease caused by a malignant tumor that secretes gastrin (gastrinoma). Gastrinomas typically occur in the pancreas or the duodenum.

Objective

To describe the incidence and prognosis of very unusual gastrinomas originating in the hepatobiliary tract.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This study included 223 consecutive patients at the National Institutes of Health and Stanford University Hospital who were enrolled in a prospective protocol to treat ZES using proton pump inhibitors to control acid hypersecretion and surgical resection to ameliorate the tumoral process. Data were collected from June 1982 to August 2017.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Incidence, location, surgical results, and cure rate and overall survival among patients with gastrinomas that originate in the liver or bile ducts. Cure was defined as serum gastrin levels within the reference range, negative results of a secretin test, and no tumor found on imaging.

Results

Of the 223 patients who underwent surgery to remove gastrinomas, 7 (3.1%) had liver or biliary tract primary tumors, including 5 men and 2 women (mean age at diagnosis, 43 years; range 27-54 years). The mean serum gastrin level was 817 pg/mL (range, 289-2700 pg/mL). Each patient had positive results of a secretin test. None had evidence of multiple endocrine neoplasia 1. Four patients had primary tumors in the liver (1 in segment II, 2 in segment IV, and 1 in segment V); 3, in the bile duct (1 in the right hepatic duct, 1 in the left hepatic duct, and 1 in the common hepatic duct). Surgical resection required 1 right hepatic lobectomy, 1 left lateral segmentectomy, 2 left hepatic lobectomies, 1 central hepatectomy, and 2 bile duct resections. Four patients had nodal metastases, and no patient had distant metastases. No operative deaths occurred, but 3 patients had complications, including bile duct stricture, portal vein stricture, and biliary fistula. Each patient was disease free in the immediate postoperative period, and 3 had recurrences in the liver and portal lymph nodes (at 3, 11, and 15 years). Three patients (43%) remained free of disease at follow-up ranging from 24 months to 26 years.

Conclusions and Relevance

Primary gastrinomas of the hepatobiliary tract are uncommon (3%), but the hepatobiliary system is the second most frequent extraduodenopancreatic primary location (after the lymph nodes). These tumors can occur outside the gastrinoma triangle and must be specifically considered. Furthermore, their discovery changes the operative approach because aggressive liver or bile duct resection is indicated, with high rates of long-term cure and survival and acceptable rates of complications. In addition, their discovery dictates that lymph nodes in the porta hepatis should be routinely excised because nearly 50% of patients will have lymph node metastases.

Introduction

Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (ZES) is the second most common functional neuroendocrine tumor (NET). Zollinger-Ellison syndrome is one of the most difficult NETs to manage because the symptoms of peptic ulcer disease and diarrhea may be life threatening, and the tumor may be malignant and also life threatening. Because ZES is rare, physicians usually require years to make the correct diagnosis. Once the symptoms of ZES are controlled medically with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), the workup continues with imaging studies to identify and localize the extent of tumor. Most gastrinomas in patients with ZES are localized to the duodenum (70%-90%) or the pancreas (2%-30%), but ectopic sites, including the ovary, stomach, lymph nodes, heart, liver or bile ducts, and rarely other sites, have been reported.

Primary gastrinomas of the hepatobiliary tract are controversial because duodenopancreatic gastrinomas characteristically metastasize to the liver; therefore, distinguishing whether an NET containing gastrin in the liver is a primary or secondary tumor can be difficult. Furthermore, the biliary tract is not always well explored because lymph node metastases within the pancreatic head area are frequently found in patients with gastrinoma, often without a primary localized tumor, presumably because a small duodenal primary tumor is missed. Furthermore, because fasting serum gastrin levels can normalize transiently after a noncurative resection, careful follow-up with functional (fasting serum gastrin levels and secretin testing) and detailed imaging studies are required to establish that the resected gastrinoma was actually a primary tumor. Thus, limited information, primarily from case reports on hepatobiliary gastrinomas, is available. Liver metastases have been associated with a greater chance of subsequent death from gastrinoma, whereas a primary tumor of the liver may be curable. Therefore, a better understanding of possible primary hepatobiliary gastrinomas could markedly affect clinical management in some patients with ZES.

Methods

Since 1982 at the National Institutes of Health and 2003 at Stanford University Hospital, 223 patients with ZES were included in a prospective strategy to perform surgical exploration for cure, as described previously. The main outcomes measured were overall survival, disease-related survival, disease-free status, the need for reoperation, and time to recurrence. After controlling the gastric acid hypersecretion with histamine H2 receptor antagonists or PPIs, confirming the diagnosis, and establishing the possible presence of multiple endocrine neoplasia 1 (MEN1), all patients underwent detailed imaging studies, including a computed tomographic (CT) scan with intravenous contrast, magnetic resonance imaging with gadolinium, ultrasonography, and somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (since 1994 using indium In 111–labeled DTPA-D-Phe–octreotide, 6 mCi, with whole-body, planar, and single-photon emission CT views or more recently using gallium 68–labeled DOTATOC positron emission tomography and CT). Patients were entered into a prospective study approved by the institutional review board of the National Institutes of Health and invited to undergo surgery to remove the tumor if they had no comorbid medical conditions that markedly limited life expectancy, had an apparently operable tumor, and if MEN1 was present, had a tumor of at least 2.0 to 2.5 cm in diameter. All patients provided written informed consent.

Data were collected from June 1982 to August 2017. The diagnosis of ZES was based on results of acid secretory studies, measurement of fasting serum levels of gastrin, and the results of secretin and/or calcium provocative tests. Basal and maximal acid output were determined for each patient using methods described previously. Doses of oral gastric antisecretory drug were determined as described previously. All patients referred with a diagnosis of possible ZES underwent an evaluation to establish the diagnosis of ZES and to determine whether MEN1 was present and studies to determine the suitability of surgical exploration for cure. These latter studies included tumor localization studies, studies to determine the presence or absence of MEN1, and studies to determine the presence of another disease that might contraindicate surgery. The presence of MEN1 was established by assessing levels of plasma hormones (intact and midmolecule parathyroid hormone, prolactin, insulin, proinsulin, and glucagon), serum calcium (ionized and total), and glucose as well as personal and family history. The operative techniques have been described previously. Patients underwent evaluation for disease-free status immediately after surgery (ie, 2 weeks after resection), within 3 to 6 months after resection, and then yearly. Disease-free status was defined as no evidence of tumor on conventional imaging studies, fasting gastrin levels within reference range, and negative results of secretin provocative testing as described previously. Persistent postoperative disease was defined as any persistent elevation of fasting serum gastrin level and/or a positive secretin test result. A postresection recurrence was defined as occurring in a patient who was initially disease free after resection but then lost disease-free status at follow-up evaluation by developing positive findings on imaging studies that were compatible with a recurrent pancreatic NET and/or recurrent elevated fasting serum gastrin levels or positive secretin provocative test results. The Fisher exact test was used for 2-group comparisons. All continuous variables were reported as means (SEM). The probabilities of survival were calculated and plotted according to the Kaplan-Meier method.

The following criteria were used to identify patients with likely hepatobiliary primary gastrinomas: the patient had to undergo a detailed exploratory laparotomy as described above; a possible primary gastrinoma was found only in the hepatobiliary area on surgical exploration or imaging studies; during detailed follow-up with imaging studies as described above, no other primary gastrinoma was found; and after resection of the hepatobiliary primary gastrinoma, the patient was disease free for at least 1 year. Seven patients met these criteria. The short-term follow-up of 3 of these patients was included in a previous report of liver surgery in patients with gastrinomas with potentially resectable disease in the liver.

Results

Of the 223 patients in our series with ZES, 7 (3%) had primary gastrinomas of the hepatobiliary tract (5 men and 2 women; mean age, 43 years; range, 27-54 years). None of these patients had MEN1. Each patient had typical signs and symptoms of ZES with peptic ulcer disease and diarrhea due to acid hypersecretion. Each had an elevated fasting serum gastrin level. Mean preoperative serum gastrin level was 817 pg/mL (reference level, <100 pg/mL), with a range of 289 to 2700 pg/mL (to convert to picomoles per liter, multiply by 0.481). Each patient achieved control of all symptoms of peptic ulcer disease and diarrhea with a PPI. The usual PPI treatment consisted of oral omeprazole, 40 mg/d. Each patient gained weight during PPI treatment. Each was found to have a primary gastrinoma of the liver (n = 4) or the bile duct (n = 3).

Each patient underwent advanced imaging studies that did not show any tumors outside the hepatobiliary area. Six patients underwent a single hepatobiliary gastrinoma resection. One patient underwent 3 resections. Initially, the patient underwent a central hepatectomy for a 5.5-cm tumor in liver segments V and VIII and was rendered disease free. The patient developed a recurrence of ZES at 11 years postoperatively and was found to have a large 5-cm recurrence in the right posterior sector (Figure 1) that was subsequently excised surgically. In addition, the patient had 5 positive lymph node metastases in the porta hepatis that were surgically removed. Postoperatively, the patient was found to be free of disease, but 4 years later, hypergastrinemia and diarrhea developed, and the patient had a liver gastrinoma in segments VI and VII (Figure 2) and 1 positive celiac lymph node that was removed at a third operation. The postoperative fasting serum gastrin level was within reference limits, but the secretin test result was positive. The patient is included as alive with disease.

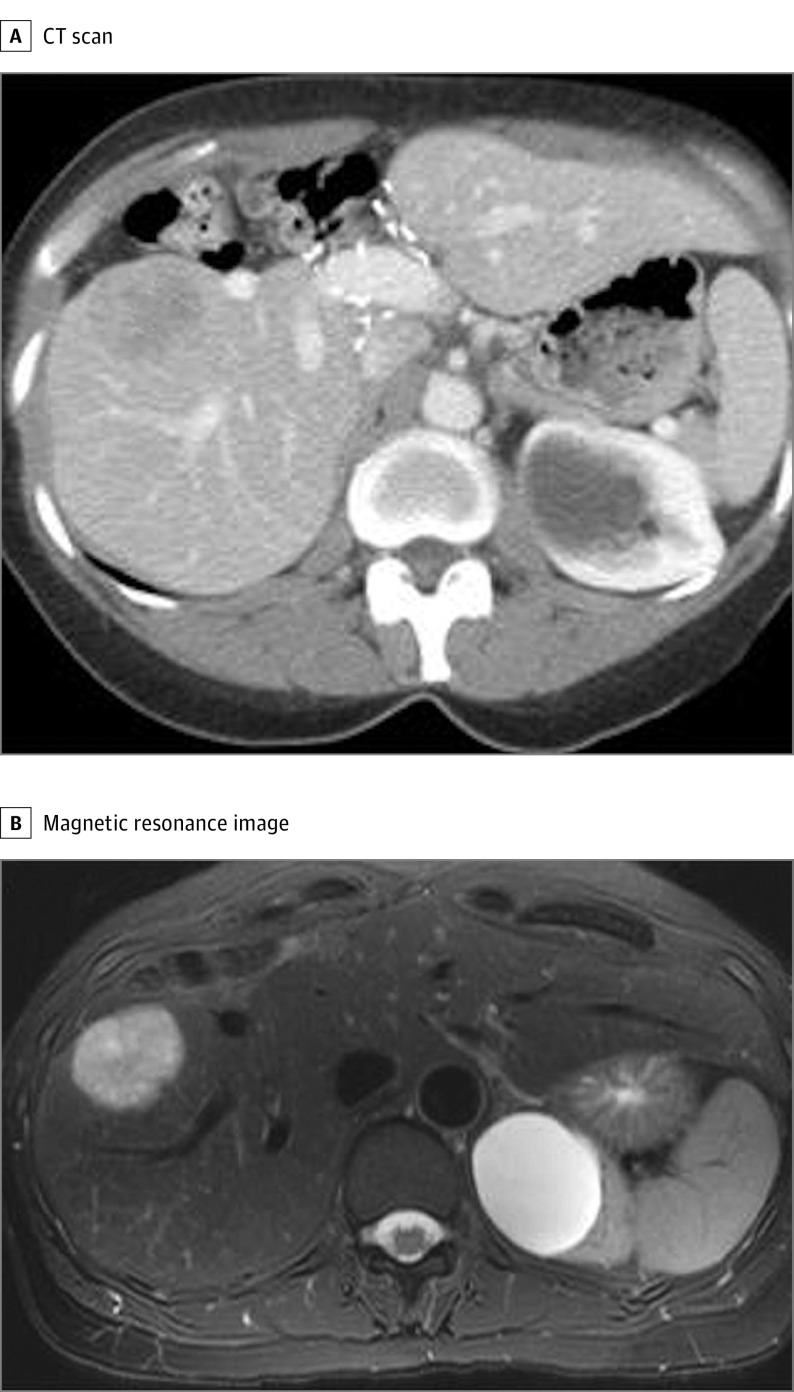

Figure 1. Recurrent Liver Gastrinoma in a Patient With Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome.

The computed tomographic (CT) scan (A) and magnetic resonance image (B) show a 5-cm recurrent tumor in liver segment VI 11 years after the initial central hepatectomy.

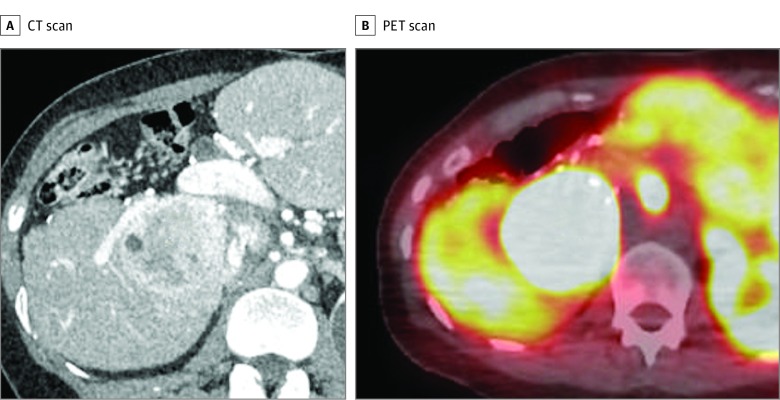

Figure 2. Second Recurrent Liver Gastrinoma in a Patient With Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome.

A, Computed tomographic (CT) scan of the patient in Figure 1 shows a new recurrence in liver segments VI and VII 4 years after the first recurrent tumor excision and 15 years after the initial central hepatectomy. B, Gallium 68–labeled DOTATOC positron emission tomographic (PET) scan shows that the recurrent tumor takes up the somatostatin analogue and is consistent with a gastrinoma.

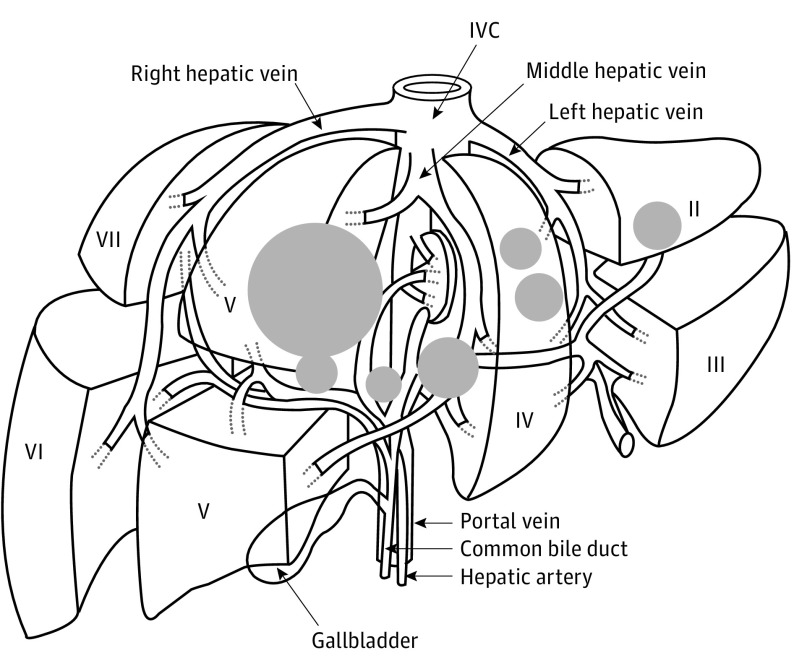

Of the 7 hepatic or bile duct primary gastrinomas, the final pathologic evaluation demonstrated that 4 were in the liver and 3 were within a major bile duct. The locations of the 4 primary tumors in the liver included segment II (n = 1), segment IV (n = 2), and segment V (n = 1) (Figure 3). The location of the 3 primary bile duct tumors were at the bifurcation of the common hepatic duct (n = 1), in the left hepatic duct (n = 1), and in the right hepatic duct (n = 1) (Figure 3). The mean primary liver and bile duct gastrinoma tumor size was 2.6 cm, with a range of 1.4 to 5.5 cm. The surgical procedures included 1 right hepatic lobectomy, 1 left lateral segmentectomy, 2 left hepatic lobectomies, 1 central hepatectomy followed by a tumor excision and a subsequent right posterior sectorectomy, 4 portal lymph node dissections (3 at the initial operation and 1 at a second operation), 1 celiac lymph node dissection at a third operation, 2 bile duct resections, and 3 Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomies.

Figure 3. Liver Diagram of the Location and Relative Size of Hepatic Gastrinomas.

The liver primary tumors are in segments II, IV, and V. The primary bile duct tumors involve the right, common, and left hepatic bile ducts. The size of the circles indicates the relative size of the tumor. IVC indicates inferior vena cava.

Lymph node metastases were found in each of the 4 patients who underwent a portal and/or celiac lymph node dissection. Three dissections were performed at the initial operation; 1, at a subsequent operation; and 1, at a third operation. None of the patients had distant metastases. Operative complications included 2 bile duct leaks that healed without further intervention. One patient developed narrowing of the portal vein with mild portal hypertension. All 7 patients were disease free for at least 1 year postoperatively, with 6 of 7 patients (86%) having no evidence of ZES at the second yearly postoperative evaluation. Three patients had recurrences at 3, 11, and 15 years after resection. One of these patients with recurrence subsequently became disease free after operations at 11 and 15 years postoperatively. However, at long-term follow-up (median, 13 years; range, 24 months to 26 years), 3 (43%) remained disease free, 1 had died of progressive metastatic tumor at 7 years, and 3 were alive with disease. During follow-up in all patients, imaging studies showed no evidence of a gastrinoma outside the liver and adjacent portal or celiac lymph nodes.

Discussion

Gastrinomas were the second functional pancreatic NET syndrome described (in 1955) after insulinomas, and like insulinomas, they were originally thought to occur in the pancreas. However, it has become apparent that gastrinomas differ markedly from insulinomas in their primary tumor location. Whereas extrapancreatic insulinomas are extremely rare (<0.1%), currently only 10% to 30% of gastrinomas are pancreatic in location, with 70% to 90% occurring in the duodenum. At present, even with extensive imaging and detailed surgical exploration, no primary tumor has been found in the duodenum or the pancreas in a proportion of patients (10%-30%). Primary gastrinomas have been reported in numerous other locations, including the lymph nodes, stomach, mesentery, ovaries, heart, lung, hepatobiliary tract, jejunum, and, rarely, in other locations. Except for ovarian gastrinomas, which are well established but rare, and lymph node primary tumors, for which existence is controversial but which made up 10% of primary gastrinomas in a previous series, descriptions of the other locations are uncommon (<1%), usually in case reports, and not clearly established. In these uncommon locations, establishing that the resected NET is the primary gastrinoma can be difficult. This difficulty occurs because numerous gastrointestinal tract NETs can have gastrin found immunocytochemically, but the gastrin is not secreted and the NETs are not causing ZES. Furthermore, gastrinomas can metastasize widely or invade other tissues, and when the metastases are resected, the fasting serum gastrin level can decrease transiently often to reference range, although the true primary gastrinoma is still present. The patient is assumed to be cured unless prolonged follow-up is performed with secretin testing and imaging. Furthermore, duodenal gastrinomas can be small (1-5 mm) and easily missed; thus, another site could be thought to be a primary site.

Primary hepatobiliary gastrinomas have been reported in a small number of case reports (<3 cases/report) in patients with sporadic ZES and with MEN1 with ZES. However, for the aforementioned reasons, their existence is questioned and their frequency and natural history, including presentation, resectability, possible cure, and pattern of recurrence, are unknown. We should address these factors because important changes might result in the surgical approach, prognosis, follow-up, and subsequent treatment of the patient. In one case, a patient with a surgically resected hepatobiliary gastrinoma could be treated as having a primary resection and, in another case, as having metastatic disease to the liver, which carries a poor prognosis and more aggressive treatment.

Our results support the conclusion that primary gastrinomas of the hepatobiliary tract in patients with sporadic ZES (ie, without MEN1) do occur. One could dispute this conclusion and suggest that a small duodenal primary tumor or a primary tumor in another location was missed and that the gastrinomas are not hepatobiliary primary tumors but hepatic metastases. Our study supports the existence of hepatobiliary primary tumors. First, each patient had only a hepatobiliary NET identified on the best possible imaging study that was available at the time. All patients had magnetic resonance imaging and CT examinations with contrast infusions, and most had somatostatin receptor scintigraphy, with one having a subsequent DOTATOC positron emission tomographic somatostatin receptor scintigraphy scan, which is the most sensitive imaging modality available at present. Each of these examinations identified a hepatobiliary location as the only possible primary site of disease. Second, after surgical excision of the hepatobiliary gastrinoma, all patients were biochemically cured of ZES for a minimum of 1 year. A previous study has demonstrated that if a recurrence occurs after gastrinoma resection, in more than 95% of such patients, the recurrence occurs within 6 to 12 months; if the patient is disease free at 1 year, the positive predictive value for long-term cure is 95%. Third, the long-term cure rate with a median follow-up of 13 years was 43%, which is similar to the reported long-term cure rate for gastrinomas excised from the duodenum or pancreas and better than results reported for patients after liver resection for metastatic gastrinoma.

Our results demonstrate that primary hepatobiliary gastrinomas occur in 3% of patients with ZES, which is more than 10 times the frequency of primary gastrinomas in the ovaries (ie, <0.3% in our series) and of gastrinomas in other rare ectopic sites, such as the stomach, mesentery, heart, or jejunum or gastrinomas due to lung cancer (<0.2%). Primary lymph node gastrinomas are reported in 0 to 10% of patients with ZES undergoing surgical exploration and occurred in a previous series in 10% of patients who had surgical exploration. Therefore, the hepatobiliary system is the second most frequent extraduodenopancreatic site for a primary gastrinoma to occur and thus needs to be considered when a duodenal or pancreatic gastrinoma is not found at exploration. This latter point is important and can affect the surgical approach.

Our results also provide support for the proposal that primary gastrinomas can occur in the liver and the biliary tract, as has been reported in previous case reports. In our series, 4 of 7 primary hepatobiliary gastrinomas (57%) were found in the liver and the remaining 3 (43%) in the biliary tract, suggesting that approximately an equal proportion occur in each location. This distribution is at odds with the frequency of possible hepatic or biliary tract gastrinomas causing ZES reported in the literature. Previous reviews of literature on hepatobiliary NETs report that 20 to 25 patients with sporadic ZES and proposed hepatic gastrinomas have been described compared with only 5 patients with sporadic ZES and possible biliary tract gastrinomas, which suggests that hepatic gastrinomas are more frequent than biliary tract gastrinomas. Coupled with the fact that biliary tract gastrinomas can be easily missed because they can occur within the bile duct or can be attached to the duct and mistaken for possible lymph node metastases, our data raise the possibility that gastrinomas at this site occur more frequently than previously reported.

One feature of the present study that was previously not generally recognized is that hepatobiliary primary tumors often metastasize to regional lymph nodes and lymph nodes within the porta hepatis and celiac axis, and they can recur locally after resection. In various reports involving 27 cases of possible hepatobiliary gastrinomas, only 3 patients (11%) were reported to have lymph node metastases and only 3 (11%) had recurrent disease after resection, suggesting that hepatobiliary gastrinomas might be less invasive than duodenopancreatic primary gastrinomas. In our study, 4 of the 7 patients with long-term follow-up (57%) had recurrent disease. Furthermore, 3 patients (43%) had lymph node metastases during the original surgery that were identified and found by portal lymph node dissection. Nonimaged portal and celiac lymph node metastases were also identified in 1 patient with liver recurrence at 11 years after resection (Figures 1 and 2). Therefore, 4 patients (57%) had regional lymph node metastases, similar to rates seen for duodenal or pancreatic primary gastrinomas. This finding suggests that regardless of the results of the imaging studies, if a hepatobiliary primary gastrinoma is apparent and considered as a working diagnosis, a portal lymph node dissection should be performed at the time of surgery. This procedure has a high probability of demonstrating and removing lymph node metastases.

The exact origin of hepatobiliary tract gastrinomas is unclear. Three theories have been proposed, including differentiation of ectopic pancreatic or adrenal tissue in the liver, transformation of malignant stem cells in the liver, and transformation of neuroendocrine cells in the intrahepatic or biliary hepatobiliary ducts. The bile duct cells contain NET argentaffin cells, some of which show gastrin immunoreactivity. In our series, hepatobiliary tract gastrinomas were identified in 3 of the 7 tumors as originating within the bile duct. Although bile ducts are scattered throughout the liver and neuroendocrine cells can be seen within them, we have no direct proof that the other 4 hepatic gastrinomas originated from them, as proposed in other studies.

Limitations

The limitations of this study include the impossibility of being certain that a primary gastronome outside the liver and bile ducts was not missed. DOTATOC scans, which are the most sensitive test for gastrinoma detection, were not available for most of the study period. When the earlier patients underwent evaluation, an extrahepatic gastrinoma may have been missed, although we do not believe this result to be the case.

Conclusions

Primary hepatobiliary tract gastrinomas were found in 3% of patients with sporadic ZES, and the hepatobiliary system is the second most frequent extraduodenopancreatic primary location of gastrinomas (after the lymph nodes). Furthermore, the discovery of these gastrinomas changes the operative approach because aggressive resection is indicated; the long-term cure rate and survival rates are high and comparable with those observed among patients with duodenal or pancreatic primary gastrinomas. In addition, our data suggest that discovery of liver or biliary gastrinomas dictates removal of regional lymph nodes (portal and celiac) because nearly half of these patients will have lymph node metastases.

References

- 1.Ito T, Jensen RT. Molecular imaging in neuroendocrine tumors: recent advances, controversies, unresolved issues, and roles in management. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2017;24(1):15-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norton JA, Doppman JL, Collen MJ, et al. Prospective study of gastrinoma localization and resection in patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Ann Surg. 1986;204(4):468-479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zollinger RM, Ellison EH. Primary peptic ulcerations of the jejunum associated with islet cell tumors of the pancreas. Ann Surg. 1955;142(4):709-723. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellison EH, Wilson SD. The Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: re-appraisal and evaluation of 260 registered cases. Ann Surg. 1964;160:512-530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roy PK, Venzon DJ, Shojamanesh H, et al. Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: clinical presentation in 261 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2000;79(6):379-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roy PK, Venzon D, Feigenbaum KM, et al. Gastric secretion in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: correlation with clinical expression, tumor extent and role in diagnosis: a prospective NIH study of 235 patients and review of the literature in 984 cases. Medicine. 2001;80:189-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collen MJ, Howard JM, McArthur KE, et al. Comparison of ranitidine and cimetidine in the treatment of gastric hypersecretion. Ann Intern Med. 1984;100(1):52-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gibril F, Schumann M, Pace A, Jensen RT. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: a prospective study of 107 cases and comparison with 1009 cases from the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2004;83(1):43-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirasawa K, Yamada M, Kitagawa M, et al. Ovarian mucinous cystadenocarcinoma as a cause of Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: report of a case and review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(5):1348-1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bollen ECM, Lamers CBHW, Jansen JBMJ, Larsson LI, Joosten HJM. Zollinger-Ellison syndrome due to a gastrin-producing ovarian cystadenocarcinoma. Br J Surg. 1981;68(11):776-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Norton JA, Alexander HR, Fraker DL, Venzon DJ, Gibril F, Jensen RT. Possible primary lymph node gastrinoma: occurrence, natural history, and predictive factors: a prospective study. Ann Surg. 2003;237(5):650-657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noda S, Norton JA, Jensen RT, Gay WA Jr. Surgical resection of intracardiac gastrinoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;67(2):532-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gibril F, Curtis LT, Termanini B, et al. Primary cardiac gastrinoma causing Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1997;112(2):567-574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ito T, Cadiot G, Jensen RT. Diagnosis of Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: increasingly difficult. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(39):5495-5503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naoe H, Iwasaki H, Kawasaki T, et al. Primary hepatic gastrinoma as an unusual manifestation of Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2012;6(3):590-595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Price TN, Thompson GB, Lewis JT, Lloyd RV, Young WF. Zollinger-Ellison syndrome due to primary gastrinoma of the extrahepatic biliary tree: three case reports and review of literature. Endocr Pract. 2009;15(7):737-749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mandujano-Vera G, Angeles-Angeles A, de la Cruz-Hernández J, Sansores-Pérez M, Larriva-Sahd J. Gastrinoma of the common bile duct: immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study of a case. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;20(4):321-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martignoni ME, Friess H, Lübke D, et al. Study of a primary gastrinoma in the common hepatic duct: a case report. Digestion. 1999;60(2):187-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsalis K, Vrakas G, Vradelis S, et al. Primary hepatic gastrinoma: report of a case and review of literature. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2011;2(2):26-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Denève E, Hamoui M, Chalançon A, et al. A case of intrahepatic gastrinoma [in French]. Ann Endocrinol (Paris). 2009;70(4):242-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tonelli F, Giudici F, Nesi G, Batignani G, Brandi ML. Biliary tree gastrinomas in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(45):8312-8320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuiper P, Biemond I, Verspaget H, et al. A case of recurrent gastrinoma in the liver with a review of “primary” hepatic gastrinomas. BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009:bcr01.2009.1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tarçin Ö, Yazici D, İnce Ü, et al. Bulky gastrinoma of the common bile duct: unusual localization of extrapancreatic gastrinoma—case report. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2011;22(2):219-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu X, Aoun E, Morrissey S. Primary hepatic gastrinoma presenting as vague gastrointestinal symptoms. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012:bcr1220115327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thompson NW, Vinik AI, Eckhauser FE, Strodel WE. Extrapancreatic gastrinomas. Surgery. 1985;98(6):1113-1120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ishikawa Y, Yoshida H, Mamada Y, et al. Curative resection of primary hepatic gastrinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55(88):2224-2227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kehagias D, Moulopoulos L, Smirniotis V, Pafiti A, Ispanopoulos S, Vlahos L. Imaging findings in primary carcinoid tumour of the liver with gastrin production. Br J Radiol. 1999;72(854):207-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moriura S, Ikeda S, Hirai M, et al. Hepatic gastrinoma. Cancer. 1993;72(5):1547-1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shibata C, Naito H, Funayama Y, et al. Diagnosis and surgical treatment for primary liver gastrinoma: report of a case. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51(6):1122-1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ogawa S, Wada M, Fukushima M, et al. Case of primary hepatic gastrinoma: diagnostic usefulness of the selective arterial calcium injection test. Hepatol Res. 2015;45(7):823-826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Delgado J, Delgado B, Sperber AD, Fich A. Successful surgical treatment of a primary liver gastrinoma during pregnancy: a case report. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(5):1716-1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Díaz R, Aparicio J, Pous S, Dolz JF, Calderero V. Primary hepatic gastrinoma. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48(8):1665-1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goletti O, Chiarugi M, Buccianti P, et al. Resection of liver gastrinoma leading to persistent eugastrinemia: case report. Eur J Surg. 1992;158(1):55-57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bello Arques P, Hervás Benito I, Mateo Navarro A. Scintigraphy with 111In-octreotide in a case of primary hepatic gastrinoma [in Spanish]. Rev Esp Med Nucl. 2001;20(5):381-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Twerdahl EH, Costantino CL, Ferrone CR, Hodin RA. Primary hepatic gastrinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20(3):662-663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu PC, Alexander HR, Bartlett DL, et al. A prospective analysis of the frequency, location, and curability of ectopic (nonpancreaticoduodenal, nonnodal) gastrinoma. Surgery. 1997;122(6):1176-1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Norton JA, Doherty GM, Fraker DL, et al. Surgical treatment of localized gastrinoma within the liver: a prospective study. Surgery. 1998;124(6):1145-1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jensen RT, Niederle B, Mitry E, et al. ; Frascati Consensus Conference; European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society . Gastrinoma (duodenal and pancreatic). Neuroendocrinology. 2006;84(3):173-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ito T, Jensen RT. Primary hepatic gastrinoma: an unusual case of Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2010;6(1):57-59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weber HC, Venzon DJ, Lin JT, et al. Determinants of metastatic rate and survival in patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: a prospective long-term study. Gastroenterology. 1995;108(6):1637-1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Howard TJ, Zinner MJ, Stabile BE, Passaro E Jr. Gastrinoma excision for cure: a prospective analysis. Ann Surg. 1990;211(1):9-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thom AK, Norton JA, Axiotis CA, Jensen RT. Location, incidence, and malignant potential of duodenal gastrinomas. Surgery. 1991;110(6):1086-1091. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Norton JA, Alexander HR, Fraker DL, Venzon DJ, Gibril F, Jensen RT. Does the use of routine duodenotomy (DUODX) affect rate of cure, development of liver metastases, or survival in patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome? Ann Surg. 2004;239(5):617-625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sugg SL, Norton JA, Fraker DL, et al. A prospective study of intraoperative methods to diagnose and resect duodenal gastrinomas. Ann Surg. 1993;218(2):138-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fishbeyn VA, Norton JA, Benya RV, et al. Assessment and prediction of long-term cure in patients with the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: the best approach. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(3):199-206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berna MJ, Hoffmann KM, Long SH, Serrano J, Gibril F, Jensen RT. Serum gastrin in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, II: prospective study of gastrin provocative testing in 293 patients from the National Institutes of Health and comparison with 537 cases from the literature: evaluation of diagnostic criteria, proposal of new criteria, and correlations with clinical and tumoral features. Medicine (Baltimore). 2006;85(6):331-364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Norton JA, Fraker DL, Alexander HR, et al. Surgery to cure the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(9):635-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Berna MJ, Hoffmann KM, Serrano J, Gibril F, Jensen RT. Serum gastrin in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, I: prospective study of fasting serum gastrin in 309 patients from the National Institutes of Health and comparison with 2229 cases from the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2006;85(6):295-330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu F, Venzon DJ, Serrano J, et al. Prospective study of the clinical course, prognostic factors, causes of death, and survival in patients with long-standing Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(2):615-630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krudy AG, Doppman JL, Jensen RT, et al. Localization of islet cell tumors by dynamic CT: comparison with plain CT, arteriography, sonography, and venous sampling. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984;143(3):585-589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alexander HR, Fraker DL, Norton JA, et al. Prospective study of somatostatin receptor scintigraphy and its effect on operative outcome in patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Ann Surg. 1998;228(2):228-238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gibril F, Reynolds JC, Chen CC, et al. Specificity of somatostatin receptor scintigraphy: a prospective study and effects of false-positive localizations on management in patients with gastrinomas. J Nucl Med. 1999;40(4):539-553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leimer M, Kurtaran A, Smith-Jones P, et al. Response to treatment with yttrium 90-DOTA-lanreotide of a patient with metastatic gastrinoma. J Nucl Med. 1998;39(12):2090-2094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cherner JA, Doppman JL, Norton JA, et al. Selective venous sampling for gastrin to localize gastrinomas: a prospective assessment. Ann Intern Med. 1986;105(6):841-847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Doppman JL, Miller DL, Chang R, et al. Gastrinomas: localization by means of selective intraarterial injection of secretin. Radiology. 1990;174(1):25-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Norton JA, Warren RS, Kelly MG, Zuraek MB, Jensen RT. Aggressive surgery for metastatic liver neuroendocrine tumors. Surgery. 2003;134(6):1057-1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Norton JA, Fraker DL, Alexander HR, et al. Surgery increases survival in patients with gastrinoma. Ann Surg. 2006;244(3):410-419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.MacFarlane MP, Fraker DL, Alexander HR, Norton JA, Lubensky I, Jensen RT. Prospective study of surgical resection of duodenal and pancreatic gastrinomas in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Surgery. 1995;118(6):973-979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Frucht H, Norton JA, London JF, et al. Detection of duodenal gastrinomas by operative endoscopic transillumination: a prospective study. Gastroenterology. 1990;99(6):1622-1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kaplan ELMP. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53(282):457-481. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jensen RT, Cadiot G, Brandi ML, et al. ; Barcelona Consensus Conference Participants . ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the management of patients with digestive neuroendocrine neoplasms: functional pancreatic endocrine tumor syndromes. Neuroendocrinology. 2012;95(2):98-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sawicki MP, Howard TJ, Dalton M, Stabile BE, Passaro E Jr. The dichotomous distribution of gastrinomas. Arch Surg. 1990;125(12):1584-1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Maton PN, Mackem SM, Norton JA, Gardner JD, O’Dorisio TM, Jensen RT. Ovarian carcinoma as a cause of Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: natural history, secretory products, and response to provocative tests. Gastroenterology. 1989;97(2):468-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Norton JA, Harris EJ, Chen Y, et al. Pancreatic endocrine tumors with major vascular abutment, involvement, or encasement and indication for resection. Arch Surg. 2011;146(6):724-732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Krampitz GW, Norton JA, Poultsides GA, Visser BC, Sun L, Jensen RT. Lymph nodes and survival in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Arch Surg. 2012;147(9):820-827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Quartey B. Primary hepatic neuroendocrine tumor: what do we know now? World J Oncol. 2011;2(5):209-216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]