This cohort study uses data from integrated health systems records in 5 states to examine overall and cause-specific mortality among adolescents and young adults with a first diagnosis of psychotic disorder.

Key Points

Question

How does the risk of death increase after the first diagnosis of a psychotic disorder?

Findings

In this population-based cohort study of 11 713 individuals aged 16 to 30 years with first diagnosis of a psychotic disorder, overall mortality was 54.6 per 10 000 compared with 6.7 per 10 000 among health system outpatients. Injuries and poisonings accounted for half of all mortality among patients with psychotic disorders.

Meaning

The 3-year period after first diagnosis of a psychotic disorder may be a high-risk time for suicide and other deaths due to injury or poisoning.

Abstract

Importance

Individuals with psychotic disorders have increased mortality, and recent research suggests a marked increase shortly after diagnosis.

Objective

To use population-based data to examine overall and cause-specific mortality after first diagnosis of a psychotic disorder.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cohort study used records from 5 integrated health systems that serve more than 8 million members in 5 states. Members aged 16 through 30 years who received a first lifetime diagnosis of a psychotic disorder from September 30, 2009, through September 30, 2015, and 2 comparison groups matched for age, sex, health system, and year of diagnosis were selected from all members making an outpatient visit (general outpatient group) and from all receiving a first diagnosis of unipolar depression (unipolar depression group).

Exposures

First recorded diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, mood disorder with psychotic symptoms, or other psychotic disorder in any outpatient, emergency department, or inpatient setting.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Death within 3 years after the index diagnosis or visit date, ascertained from health system electronic health records, insurance claims, and state mortality records.

Results

A total of 11 713 members with first diagnosis of a psychotic disorder (6976 [59.6%] men and 4737 [40.4%] women; 2368 [20.2%] aged 16-17 and 9345 [79.8%] aged 18-30 years) were matched to 35 576 outpatient service users and 23 415 members with a first diagnosis of unipolar depression. During the year after the first diagnosis, all-cause mortality was 54.6 (95% CI, 41.3-68.0) per 10 000 in the psychotic disorder group compared with 20.5 (95% CI, 14.7-26.3) per 10 000 in the unipolar depression group and 6.7 (95% CI, 4.0-9.4) per 10 000 in the general outpatient group. After adjustment for race, ethnicity, and preexisting chronic medical conditions, the relative hazard of death in the psychotic disorder group compared with the general outpatient group was 34.93 (95% CI, 8.19-149.10) for self-inflicted injury or poisoning and 4.67 (95% CI, 2.01-10.86) for other type of injury or poisoning. Risk of death due to heart disease or diabetes did not differ significantly between the psychotic disorder and the general outpatient groups (hazard ratio, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.15-3.96). Between the first and third years after diagnosis, all-cause mortality in the psychotic disorder group decreased from 54.6 to 27.1 per 10 000 persons and injury and poisoning mortality decreased from 30.6 to 15.1 per 10 000 persons. Both rates, however, remained 3 times as high as in the general outpatient group (9.0 per 10 000 for all causes; 4.8 per 10 000 for injury or poisoning).

Conclusions and Relevance

Increases in early mortality underscore the importance of systematic intervention for young persons experiencing the first onset of psychosis. Clinicians should attend to the elevated suicide risk after the first diagnosis a psychotic disorder.

Introduction

People with psychotic disorders have significant excess mortality. Among people with serious mental illnesses, including schizophrenia and affective psychoses, all-cause mortality rates are 2 to 3 times those in the general population. Consequently, people with psychotic disorders die, on average, 10 to 15 years earlier than their peers.

Much of the concern regarding excess mortality among people with psychotic disorders has focused on chronic illness, especially cardiovascular disease. Long-term studies have found that most excess mortality in psychotic disorders can be attributed to various natural causes, especially cardiovascular disease. Excess mortality owing to cardiovascular disease has been attributed to a mix of factors, including adverse health behaviors (eg, smoking, a sedentary lifestyle), adverse metabolic effects of medications, and poorer access to effective general medical care.

More recent research suggests an even greater increase in mortality soon after the initial diagnosis of a psychotic disorder. In a sample of people aged 16 to 30 years with first diagnosis of a psychotic disorder in US commercial insurance claims, mortality during the following 12 months was more than 20 times the expected rate based on US general population statistics. In that sample, data were not available regarding specific causes of death. National registry studies in Denmark, Finland, and Sweden have found elevated mortality after the first hospitalization for a psychotic disorder. In a combined analysis using data from all 3 of those national registries, all-cause mortality during a mean follow-up period of 4 years was 2 to 3 times greater than in the general population. The most marked increases were seen in mortality due to suicide (15- to 30-fold increase) and other external causes (3- to 6-fold increases).

We used population-based records data from 5 large integrated health systems in the United States to examine mortality in adolescents and young adults after the first diagnosis of psychotic disorder in any treatment setting. We addressed the following 5 specific questions: (1) How does overall mortality in the year after first diagnosis of a psychotic disorder compare with mortality in matched control groups of members from the same health system? (2) Is excess mortality specific to psychotic disorders or common to other mental health conditions? (3) What specific causes of death account for excess mortality? (4) Is excess mortality explained by differences in the prevalence of preexisting chronic medical conditions? (5) How do patterns of overall and cause-specific mortality change over time after the first diagnosis of a psychotic disorder?

Methods

Participating study sites included 5 regions of Kaiser Permanente (Colorado, Northern California, Southern California, the Northwest, and Washington), which are all members of the Mental Health Research Network. All 5 health care systems provide prepaid comprehensive care (including general medical and specialty mental health care) to defined populations totaling more than 8 million members in 5 states. In each system, members are representative of service area populations in terms of age, sex, and race/ethnicity. In 2012, the source of insurance coverage for members of these health systems was Medicaid for 6%, Medicare for 13%, individual insurance (including subsidized low-income plans) for 5%, and group commercial insurance for 76%. Responsible institutional review boards for each health system approved a waiver of consent for use of deidentified records data in this research.

As members of the Mental Health Research Network, all health systems maintain standardized research databases organized according to the Health Care Systems Research Network Virtual Data Warehouse (formerly the HMO Research Network Virtual Data Warehouse) model. In each system, electronic medical records (for services provided at health care system–operated facilities) and insurance claims (for services provided by external clinicians and paid for by the health care system) are organized into a virtual data warehouse for research. Identifiable data remain at each health care system, but common data specifications facilitate multisite research using pooled deidentified data.

Cases with newly diagnosed psychotic disorder included all health system members aged 16 through 30 years who received a first recorded diagnosis of psychotic disorder in any health care setting from September 30, 2009, through September 30, 2015. During the study period, billing or encounter diagnoses from all outpatient and inpatient encounters in each health system (including emergency department, mental health specialty, primary care, and other general medical settings) were used to identify the first lifetime diagnosis of any psychotic disorder (including schizophrenia spectrum disorders, mood disorders with psychotic symptoms, and other psychotic disorders) among enrolled health plan members. Eligible International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnoses included any recorded (primary or otherwise) diagnostic codes 295.0 through 295.9, 296.04, 296.14, 296.24, 296.34, 296.44, 296.54, 296.64, 297.1, 297.3, 298.1, 298.3, 298.4, 298.8, or 298.9. Patients with other mental health diagnoses preceding the first recorded diagnosis of a psychotic disorder were not excluded. Diagnoses of substance-induced psychotic symptoms were not included, but patients with diagnoses of a substance use disorder or a record of substance use accompanying an eligible diagnosis of a psychotic disorder were included. To exclude those with preexisting diagnoses of psychotic disorder, cases were limited to those continuously enrolled in the health system for at least 12 months before the first recorded diagnosis. As previously reported, the positive predictive value of this case definition (validated against detailed review of full-text medical records) was approximately 80%.

For each case with a new diagnosis of a psychotic disorder, 3 matched control individuals were identified from all health system members making at least 1 outpatient visit regardless of diagnosis during the study period. The general outpatient group controls were frequency matched to cases by sex, health system, year of eligibility (±2 years), and age (±2 years).

To examine whether any mortality differences were specific to psychotic disorders, 2 additional matched controls per case were selected from health system members receiving a first recorded diagnosis of unipolar major depression without psychotic symptoms (ICD-9-CM codes 296.20, 296.21, 296.22, 296.23, 296.30, 296.31, 296.32, and 296.33) during the same period. The unipolar depression group controls were frequency matched to cases by sex, study site, year of diagnosis (±2 years), and age (±2 years).

In the psychotic disorder case group and the unipolar depression control group, the first recorded diagnosis (of psychotic disorder or unipolar depression) was considered to be the index date for ascertainment of subsequent mortality. For the general outpatient control group, the first qualifying outpatient visit during the eligibility year was considered to be the index date.

For all 3 groups, deaths occurring during the 3-year period after the index date were identified from any of the following 3 different sources: health system electronic health records and insurance claims for deaths occurring in hospitals or emergency departments, health insurance enrollment records for deaths reported to health plans by payers or purchasers, and state death certificate data. Information on the specific cause of death was available for deaths ascertained from state death certificate data or electronic health records, but cause of death was not available for deaths ascertained solely from insurance enrollment records. Specific causes of death, when known, were classified as suicide or self-inflicted injury (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision [ICD-10] codes U03, X60-X84, and Y87.0), accidental injury or poisoning (ICD-10 codes V01-X59 and Y85-Y86), assault (ICD-10 codes U01-U02, X85-Y09, and Y87.1), cancer (ICD-10 codes C00-C97), and diabetes and cardiovascular disease (ICD-10 codes E10-E14, I00-I09, I11, and I20-I51).

Chronic medical conditions before the index diagnosis or index date were identified using the Charlson comorbidity index categories, calculated using all outpatient or inpatient diagnoses recorded during the 12 months before the index date. Primary analyses considered deaths during the first year after each person’s index date. Initial descriptive analyses examined baseline demographic and clinical characteristics in case and control samples. Additional descriptive analyses examined point estimates and 95% CIs for all-cause mortality and for specific causes of death during the first 12 months in all 3 groups. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to compare hazards of all-cause mortality and cause-specific mortality during the first 12 months for cases with each of the control groups and adjusting for race/ethnicity and preexisting chronic medical conditions. Secondary analyses examined all-cause mortality and cause-specific mortality during the first 3 years after the index date (the longest period for which data were available for more than half of the patient sample).

Results

Using our inclusion criteria, we identified 11 713 health system members (6976 [59.6%] men and 4737 [40.4%] women; 2368 [20.2%] aged 15-17 and 9345 [79.8%] aged 18-30 years) with a new diagnosis of a psychotic disorder. Initial diagnoses were schizophrenia spectrum disorder for 1172 (10.0%), mood disorder with psychosis (including schizoaffective disorder) for 2577 (22.0%), and other psychotic disorder for 7964 (68.0%). The care setting of the initial diagnosis was a hospital in 2692 (23.0%), an emergency department in 2328 (19.9%), a mental health outpatient facility in 4899 (41.8%), and a general medical outpatient facility in 1794 (15.3%). Baseline characteristics of patients with a psychotic disorder and the general outpatient and unipolar depression control groups are shown in Table 1. Distributions of age and sex were similar for cases and controls, reflecting the aforementioned matching process. Compared with either control group, cases with first diagnosis of a psychotic disorder were more often black (14.7% vs 7.8% and 9.1%) and less often non-Hispanic white (43.2% vs 51.0% and 39.3%). Chronic lung disease (including asthma) was the only chronic illness with an overall prevalence of greater than 1.1% in all groups. In general, prevalence of preexisting chronic illnesses among those with first diagnosis of a psychotic disorder was similar to that in the unipolar depression group and higher than that in the general outpatient group.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population.

| Characteristic | Patient Group, No. (%)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| First Diagnosis of Psychotic Disorder (n = 11 713) | First Diagnosis of Unipolar Depression (n = 23 415) | General Outpatient (n = 35 576) | |

| Male | 6976 (59.6) | 13 626 (58.2) | 20 881 (58.7) |

| Age, y | |||

| 16-17 | 2368 (20.2) | 5041 (21.5) | 7845 (22.1) |

| 18-25 | 7501 (64.0) | 14 411 (61.4) | 21 741 (61.1) |

| 26-30 | 1844 (15.7) | 3963 (16.9) | 5990 (16.8) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 5060 (43.2) | 11 930 (51.0) | 13 974 (39.3) |

| Black | 1722 (14.7) | 1825 (7.8) | 3249 (9.1) |

| Hispanic | 3030 (25.9) | 6087 (26.0) | 10 378 (29.2) |

| Asian | 948 (8.1) | 1957 (8.4) | 4375 (12.3) |

| Native American or Alaskan Native | 73 (0.6) | 159 (0.7) | 167 (0.5) |

| Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 113 (1.0) | 185 (0.8) | 335 (0.9) |

| Other or unknown | 767 (6.5) | 1272 (5.4) | 3098 (8.7) |

| Any mental health diagnosis in prior year | 6748 (57.6) | 10 667 (45.6) | 2695 (7.6) |

| Any substance use disorder diagnosis in prior year | 2972 (25.4) | 2275 (9.7) | 621 (1.7) |

| Charlson comorbidity indexb | |||

| ≥1 | 1569 (13.4) | 2718 (11.6) | 2247 (6.3) |

| ≥2 | 179 (1.5) | 227 (1.0) | 190 (0.5) |

| Specific chronic conditions | |||

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 1303 (11.1) | 2309 (9.9) | 1848 (5.2) |

| Diabetes | 115 (1.0) | 268 (1.1) | 219 (0.6) |

| Any malignant disease | 48 (0.4) | 57 (0.2) | 83 (0.2) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 57 (0.5) | 41 (0.2) | 21 (0.1) |

| Renal disease | 31 (0.3) | 44 (0.2) | 42 (0.1) |

| Rheumatic disease | 24 (0.2) | 23 (0.1) | 38 (0.1) |

| Hemiplegia or paraplegia | 35 (0.3) | 26 (0.1) | 16 (0.04) |

Percentages have been rounded and may not total 100.

Higher scores indicate more comorbidities.

All-cause and cause-specific mortality rates among cases and controls during the 12 months after the first diagnosis date or index date are shown in Table 2. Overall mortality after the first diagnosis of a psychotic disorder (54.6 per 10 000; 95% CI, 41.3-68.0 per 10 000) was approximately 8 times that in the general outpatient group (6.7 per 10 000; 95% CI, 4.0-9.4 per 10 000), with deaths due to injury or poisoning (including self-harm, unintentional harm, and assaults) accounting for most of that difference. Overall mortality among those with a first diagnosis of psychotic disorder was almost 3 times that observed in the unipolar depression group (20.5 per 10 000; 95% CI, 14.7-26.3 per 10 000). Again, deaths due to self-harm, unintentional harm, and assaults accounted for most of that difference.

Table 2. Twelve-Month Total and Cause-Specific Mortality Rates.

| Cause of Death | Patient Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Diagnosis of Psychotic Disorder (n = 11 713) |

First Diagnosis of Unipolar Depression (n = 23 415) |

General Outpatient (n = 35 576) |

||||

| No. of Patients | Rate per 10 000/y (95% CI) | No. of Patients | Rate per 10 000/y (95% CI) | No. of Patients | Rate per 10 000/y (95% CI) | |

| All | 64 | 54.6 (41.3-68.0) | 48 | 20.5 (14.7-26.3) | 24 | 6.7 (4.0-9.4) |

| Self-inflicted injury or poisoning | 22 | 18.8 (10.9-26.6) | 26 | 11.1 (6.8-15.4) | 2 | 0.6 (0.0-1.3) |

| Unintentional injury or poisoning | 11 | 9.4 (3.9-14.9) | 5 | 2.1 (0.3-4.0) | 6 | 1.7 (0.3-3.0) |

| Assault | 3 | 2.6 (0.0-5.5) | 1 | 0.4 (0.0-1.3) | 3 | 0.8 (0.0-1.8) |

| Cancer | 8 | 6.8 (2.1-11.6) | 2 | 0.9 (0.0-2.0) | 5 | 1.4 (0.2-2.6) |

| Heart disease or diabetes | 2 | 1.7 (0.0-4.1) | 4 | 1.7 (0.0-3.4) | 6 | 1.7 (0.3-30) |

| Other known cause | 9 | 7.7 (2.7-12.7) | 3 | 1.3 (0.0-2.7) | 2 | 0.6 (0.0-1.3) |

| Cause unavailable | 9 | 7.7 (2.7-12.7) | 7 | 3.0 (0.8-5.2) | 0 | 0 |

Results of Cox proportional hazards regression models with and without adjustment for race/ethnicity and medical comorbidity before diagnosis are shown in Table 3. After adjustment, the hazard ratio for overall mortality in the year after a first psychotic disorder diagnosis was 6.92 (95% CI, 4.30-11.14) compared with the overall mortality observed in the general outpatient group and 2.55 (95% CI, 1.77-3.72) compared with the overall mortality observed in the unipolar depression group. Deaths due to self-inflicted injury or poisoning were more than 30 times as likely in the group with new psychotic disorder diagnoses (hazard ratio, 34.93; 95% CI, 8.19-149.10) as in the general outpatient group, but mortality associated with self-harm was not significantly more likely in the psychosis group than in the unipolar depression group (hazard ratio, 1.62; 95% CI, 0.92-2.87; ie, the 95% CI included 1.00).

Table 3. Twelve-Month Relative Hazard of Death Among Patients With First Diagnosis of a Psychotic Disorder.

| Cause of Death | Comparison Patient Group, HR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Outpatient | First Diagnosis of Unipolar Depression | |||

| Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | |

| All | 8.06 (5.04-12.90) | 6.92 (4.30-11.14) | 2.63 (1.80-3.83) | 2.55 (1.77-3.72) |

| Self-inflicted injury or poisoning | 32.36 (7.59-138.00) | 34.93 (8.19-149.10) | 1.62 (0.92-2.87) | 1.62 (0.91-2.88) |

| Other injury or poisoning | 4.76 (2.06-10.99) | 4.67 (2.01-10.86) | 4.67 (1.79-12.16) | 4.66 (1.79-12.12) |

| Heart disease or diabetes | 1.02 (0.21-5.05) | 0.78 (0.15-3.96) | 1.00 (0.18-5.46) | 0.94 (0.17-5.15) |

| Other known cause | 7.46 (3.09-17.99) | 4.63 (1.89-11.33) | 6.81 (2.51-18.46) | 6.11 (2.25-16.58) |

| Cause unavailable | NAb | NAb | 2.58 (0.96-6.92) | 2.50 (0.93-6.72) |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; NA, not applicable; OR, odd ratio.

Adjusted for Charlson comorbidity index (0 vs ≥1; higher scores indicate more comorbidities) and race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, Native American or Alaskan Native, and other or unknown vs black, Asian, Hispanic, and Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander).

Cannot estimate owing to 0 events in the comparison group.

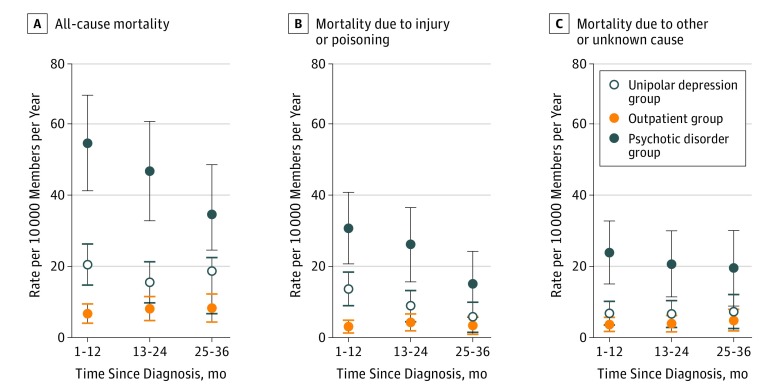

The Figure shows overall and cause-specific mortality rates during the 3 years after each person’s first diagnosis or index date. In the group with first diagnosis of a psychotic disorder, overall mortality decreased from 54.6 to 27.1 per 10 000 persons during the 3 years after diagnosis, but deaths due to injury or poisoning continued to account for approximately half of all mortality. After 3 years, however, overall mortality remained more than twice as high as that in the unipolar depression group (27.1 vs 13.8 per 10 000 persons) and more than 3 times as high as that in the general outpatient group (27.1 vs 9.0 per 10 000 persons). Similarly, mortality due to injury or poisoning remained more than 2 times as high as that in the unipolar depression group (15.1 vs 7.5 per 10 000 persons) and 3 times as high as that in the general outpatient group (15.1 vs 4.8 per 10 000 persons).

Figure. Mortality Rates During 3 Years Among Health Plan Members.

Members included patients who received a first diagnosis of a psychotic disorder (psychotic disorder group) and matched comparison groups selected from members making at least 1 outpatient visit (outpatient group) and members receiving a first diagnosis of unipolar depression (unipolar depression group). Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

Discussion

In this population-based sample of health system members receiving first diagnosis of a psychotic disorder in any care setting, we observed an all-cause mortality rate approximately 8 times that observed in a matched control group of outpatient service users and 3 times that observed in a matched control group of members receiving a first diagnosis of unipolar depression. Compared with the general outpatient group, excess mortality during the year after a first diagnosis of psychosis was largely attributable to injuries and poisonings, including deaths due to self-harm, unintentional harm, or assault. In persons with a new diagnosis of a psychotic disorder, overall mortality and mortality due to injuries and poisonings decreased gradually during the 3 years after the diagnosis. However, overall mortality and mortality due to injury or poisoning remained elevated in comparison with the outpatient health service users or with health plan members with a new diagnosis of unipolar depression.

Our data indicate a marked increase in the risk of death after the first diagnosis of a psychotic disorder in adolescents and young adults, but the 8-fold increase in mortality in this sample is smaller than the 20-fold increase reported by Schoenbaum and colleagues. Some of that discrepancy may represent random variation, given the small number of deaths in this sample. Some of the discrepancy may reflect differences in methods. Mortality data were obtained from electronic health records, state vital records, and insurance coverage data rather than from Social Security Administration records; thus, deaths among patients disenrolling from the health system and moving to a different state could have been missed. A control group selected from outpatient service users would be expected to have a higher mortality rate than a general population sample. Even the lower estimate of an 8-fold difference in mortality, however, represents an increase in risk among adolescents and young adults soon after the first clinical presentation with psychotic symptoms.

Approximately 75% of members of these health systems were enrolled through commercial insurance, and the sample reported by Schoenbaum and colleagues was limited to those covered by commercial insurance. We might observe even greater excess mortality in a population with a higher proportion of low-income or disadvantaged patients.

New diagnosis of a psychotic disorder could sometimes reflect misdiagnosis of primary psychotic disorder in persons with psychotic symptoms attributable to medical illness. In this scenario, subsequent excess mortality would be owing to that underlying illness rather than causally associated with psychotic disorder. We observed a higher rate of preexisting medical illness in the psychotic disorder group compared with the general outpatient group, but accounting for differences in preexisting illness had an only minimal association with mortality differences.

Context

Excess mortality among persons with first diagnosis of a psychotic disorder was less substantial when compared with that observed among persons with unipolar depression. Nevertheless, overall mortality and mortality due to injuries or poisonings (the largest single category) were more than twice as high after the diagnosis of a psychotic disorder than after diagnosis of unipolar depression. This difference was maintained for 3 years. Although the 95% CIs were wide for less common causes of death, mortality rates for most categories were higher after diagnosis of a psychotic disorder.

Our data are consistent with previous epidemiologic research that describes an elevated risk of death due to injury or poisoning soon after the onset of a psychotic disorder. Those previous studies have also found elevated rates of suicide or death due to unnatural causes soon after the first diagnosis. Similar to findings in our sample, approximately half of all early deaths after the first diagnosis of a psychotic disorder were attributable to suicide or other types of injury or poisoning.

Our data and other recent reports indicate that causes of excess mortality soon after diagnosis differ significantly from the chronic illnesses associated with long-term increases in mortality among persons with psychotic disorders. In the sample in our study, deaths due to diabetes or cardiovascular disease accounted for a small proportion of all mortality within 3 years after the first diagnosis of a psychotic disorder. Furthermore, the rate of death due to diabetes or heart disease was no different soon after first diagnosis of a psychotic disorder than the rate observed in a matched sample selected from outpatient service users. Although previous research has demonstrated high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors at or soon after first diagnosis of a psychotic disorder, the mortality associated with those risk factors would not be expected to occur for many years.

Limitations

We acknowledge possible misclassification in our identification of the new diagnosis of a psychotic disorder. Given the large sample of patients, we could not individually confirm all diagnoses using full-text medical records. Consequently, we relied on a strict definition found to have a high confirmation rate or a positive predictive value in previous research from our group. Nevertheless, this definition may also have a false-positive rate of as much as 20%. The previous research suggests that most false-positive findings are owing to overdiagnosis of psychotic symptoms (ie, recording of a psychotic disorder diagnosis when psychotic symptoms are not clearly present) with a small number owing to newly recorded diagnoses in individuals with a history of diagnosis or treatment (ie, chronic rather than new cases). A significant number of false-positive findings in the psychotic disorder group would lead to a conservative bias (ie, underestimating the excess mortality after first diagnosis of a psychotic disorder).

We should also emphasize that many of those receiving a first diagnosis of a psychotic disorder may have experienced symptoms of psychosis for months or years before receiving a formal diagnosis. The records data available to us do not allow assessment of unrecognized or untreated psychotic symptoms. Diagnoses of a psychotic disorder could have been recorded before the 12-month enrollment window required for inclusion in this sample. Sensitivity analyses limiting the sample to those with longer prior enrollment yielded similar results (eTable in the Supplement). Any errors in dating the onset of psychosis would likely introduce a conservative bias by mixing those with truly new symptoms (for whom mortality risk appears to be highest) and those with long-standing symptoms that were recently diagnosed. We cannot examine mortality among those developing psychotic symptoms who died before those symptoms were diagnosed.

Conclusions

Our findings support the importance of systematic early intervention for young people experiencing the first onset of psychosis. Strong evidence supports the effectiveness of coordinated specialty care programs for improving clinical and functional outcomes. Observational studies suggest that continuous treatment with antipsychotic medication may reduce mortality among persons with psychotic disorders. Few young people with new diagnosis of a psychotic disorder actually receive coordinated or continuous care. These findings also underscore the specific importance of suicide and deaths due to injury or poisoning soon after first diagnosis of a psychotic disorder. Early intervention programs should give special attention to assessing and addressing the risk of self-harm. Clinicians caring for young people with psychotic symptoms should be aware that the 1 or 2 years after first onset of a psychotic disorder may be a period of high risk of mortality.

eTable. Sensitivity Analyses Comparing Mortality Rates With Case and Control Samples Limited to Those With at Least 24 and 36 Months of Prior Enrollment

References

- 1.Suvisaari J, Partti K, Perälä J, et al. . Mortality and its determinants in people with psychotic disorder. Psychosom Med. 2013;75(1):60-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayes JF, Marston L, Walters K, King MB, Osborn DPJ. Mortality gap for people with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: UK-based cohort study 2000-2014. Br J Psychiatry. 2017;211(3):175-181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olfson M, Gerhard T, Huang C, Crystal S, Stroup TS. Premature mortality among adults with schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1172-1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bitter I, Czobor P, Borsi A, et al. . Mortality and the relationship of somatic comorbidities to mortality in schizophrenia: a nationwide matched-cohort study. Eur Psychiatry. 2017;45:97-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(4):334-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hjorthøj C, Stürup AE, McGrath JJ, Nordentoft M. Years of potential life lost and life expectancy in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(4):295-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laursen TM, Munk-Olsen T, Gasse C. Chronic somatic comorbidity and excess mortality due to natural causes in persons with schizophrenia or bipolar affective disorder. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e24597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Druss BG, Bradford DW, Rosenheck RA, Radford MJ, Krumholz HM. Mental disorders and use of cardiovascular procedures after myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2000;283(4):506-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Westman J, Eriksson SV, Gissler M, et al. . Increased cardiovascular mortality in people with schizophrenia: a 24-year national register study [published online June 5, 2017]. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fazel S, Wolf A, Palm C, Lichtenstein P. Violent crime, suicide, and premature mortality in patients with schizophrenia and related disorders: a 38-year total population study in Sweden. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(1):44-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nordentoft M, Madsen T, Fedyszyn I. Suicidal behavior and mortality in first-episode psychosis. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2015;203(5):387-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nordentoft M, Wahlbeck K, Hällgren J, et al. . Excess mortality, causes of death and life expectancy in 270 770 patients with recent onset of mental disorders in Denmark, Finland and Sweden. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e55176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kiviniemi M, Suvisaari J, Pirkola S, Häkkinen U, Isohanni M, Hakko H. Regional differences in five-year mortality after a first episode of schizophrenia in Finland. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(3):272-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schoenbaum M, Sutherland JM, Chappel A, et al. . Twelve-month health care use and mortality in commercially insured young people with incident psychosis in the United States. Schizophr Bull. 2017;43(6):1262-1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simon GE, Coleman KJ, Waitzfelder BE, et al. . Adjusting antidepressant quality measures for race and ethnicity. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(10):1055-1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koebnick C, Langer-Gould AM, Gould MK, et al. . Sociodemographic characteristics of members of a large, integrated health care system: comparison with US Census Bureau data. Perm J. 2012;16(3):37-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arterburn DE, Alexander GL, Calvi J, et al. . Body mass index measurement and obesity prevalence in ten US health plans. Clin Med Res. 2010;8(3-4):126-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ross TR, Ng D, Brown JS, et al. . The HMO Research Network Virtual Data Warehouse: a public data model to support collaboration. EGEMS (Wash DC). 2014;2(1):1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simon GE, Coleman KJ, Yarborough BJH, et al. . First presentation with psychotic symptoms in a population-based sample. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68(5):456-461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(11):1245-1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palmer BA, Pankratz VS, Bostwick JM. The lifetime risk of suicide in schizophrenia: a reexamination. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(3):247-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mortensen PB, Juel K. Mortality and causes of death in first admitted schizophrenic patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;163:183-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robinson J, Harris M, Cotton S, et al. . Sudden death among young people with first-episode psychosis: an 8-10 year follow-up study. Psychiatry Res. 2010;177(3):305-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Srihari VH, Phutane VH, Ozkan B, et al. . Cardiovascular mortality in schizophrenia: defining a critical period for prevention. Schizophr Res. 2013;146(1-3):64-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Correll CU, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. . Cardiometabolic risk in patients with first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorders: baseline results from the RAISE-ETP study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(12):1350-1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Penttilä M, Jääskeläinen E, Hirvonen N, Isohanni M, Miettunen J. Duration of untreated psychosis as predictor of long-term outcome in schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205(2):88-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lloyd-Evans B, Crosby M, Stockton S, et al. . Initiatives to shorten duration of untreated psychosis: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;198(4):256-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marshall M, Lewis S, Lockwood A, Drake R, Jones P, Croudace T. Association between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in cohorts of first-episode patients: a systematic review. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(9):975-983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kane JM, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. . Comprehensive versus usual community care for first-episode psychosis: 2-year outcomes from the NIMH RAISE Early Treatment Program. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(4):362-372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenheck R, Leslie D, Sint K, et al. . Cost-effectiveness of comprehensive, integrated care for first episode psychosis in the NIMH RAISE Early Treatment Program. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42(4):896-906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Srihari VH, Tek C, Kucukgoncu S, et al. . First-episode services for psychotic disorders in the US public sector: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(7):705-712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tiihonen J, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Torniainen M, Alexanderson K, Tanskanen A. Mortality and cumulative exposure to antipsychotics, antidepressants, and benzodiazepines in patients with schizophrenia: an observational follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(6):600-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Torniainen M, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Tanskanen A, et al. . Antipsychotic treatment and mortality in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(3):656-663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Sensitivity Analyses Comparing Mortality Rates With Case and Control Samples Limited to Those With at Least 24 and 36 Months of Prior Enrollment