Key Points

Question

What is the optimal treatment strategy for lateral wall insufficiency (LWI)?

Findings

In this case-control study that compared the LWI grades and Nasal Obstruction Symptom Evaluation scores between 44 patients who underwent septorhinoplasty to repair LWI and 44 patients who underwent the same procedure but without LWI repair, postoperative LWI grades significantly decreased in the first group to levels similar to those in the second group. A positive linear correlation was noted between the 2 sets of scores.

Meaning

By evaluating and comparing subjective and objective outcomes of patients who underwent septorhinoplasty with or without LWI repair, surgeons can tailor surgical treatments and monitor postoperative improvements for each patient.

Abstract

Importance

Lateral wall insufficiency (LWI) is classified by the zone in which it occurs. Multiple techniques for treating LWI are described in the literature and are used, but no treatment approach has been widely adopted.

Objective

To establish an algorithm for treatment of LWI by evaluating subjective and objective outcomes of patients who underwent LWI repair and comparing these results with those of a control group who received no specific LWI repair.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This case-control study was conducted in

a tertiary referral center. In group 1, there were 44 patients who underwent septorhinoplasty to repair LWI between February 1, 2014, and May 31, 2016. In group 2, there were 44 age- and sex-matched patients who underwent cosmetic septorhinoplasty without LWI repair. Data analysis was conducted from February 1, 2014, to May 31, 2016.

Intervention

Open septorhinoplasty.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Nasal Obstruction Symptom Evaluation (NOSE) scores and LWI grades.

Results

Forty-four patients (8 men and 36 women, with a mean [SD] age of 46 [16] years) who underwent open septorhinoplasty to repair LWI and 44 age- and sex-matched patients (composed of 8 men and 36 women, with a mean [SD] age of 41 [12] years) were included in the study. The mean (SD) preoperative NOSE scores were 69.4 (22) in group 1 and 20.5 (20.8) in group 2 (P < .001). The NOSE scores in both groups significantly improved after surgery (44.7 [95% CI, −28.9 to −49.9; P < .001] and −14.5 [95% CI, −2.7 to −18.5; P = .02]), although the improvement in group 2 was not clinically significant. The mean preoperative LWI grades were higher in group 1 than in group 2 for each zone (P < .001 and P = .001) but were similar between groups for each zone after surgery. Postoperative LWI scores significantly decreased in group 1 to levels similar to that of group 2. A positive linear correlation was noted between NOSE scores and LWI grades, with the strongest correlation between preoperative zone 1 LWI grades and NOSE scores (R = 0.68). Lateral crural strut grafts were used for zone 1 LWI and alar rim grafts were used for zone 2 LWI.

Conclusions and Relevance

The LWI grading system enables surgeons to localize LWI, tailor the surgical treatment to the patient, and monitor improvements in the postoperative period.

Level of Evidence

3.

This case-control study examines and compares the outcomes of septorhinoplasty to repair lateral wall insufficiency to determine the most appropriate treatment approach.

Introduction

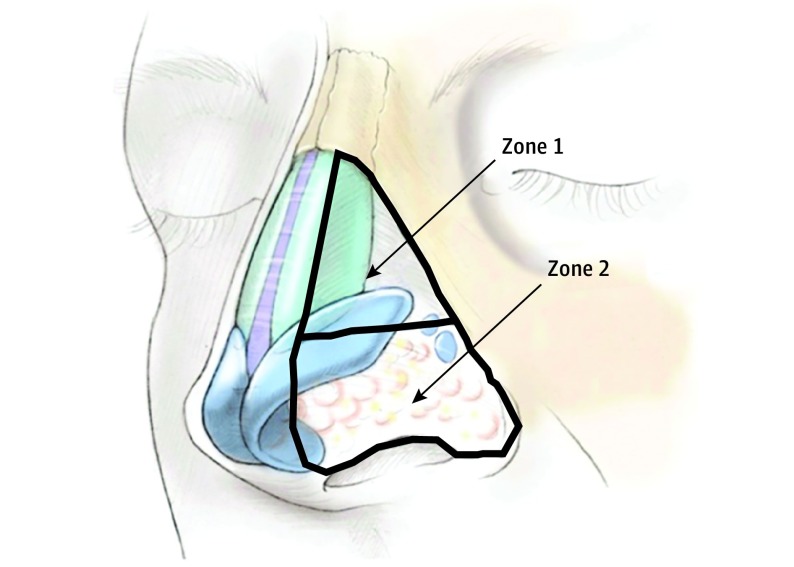

Nasal obstruction is a commonly encountered complaint in the ear, nose, and throat field and in facial plastic surgery. Lateral wall insufficiency (LWI) is one of the etiologies of nasal obstruction. Described in 2008 by the senior author (S. P. Most),1 LWI (which was previously referred to as dynamic internal and external nasal valve collapse) is classified by the zone in which it occurs (Figure 1). Zone 1 LWI occurs more cephalad and corresponds to the dynamic movement of the nasal sidewall at the level of the upper lateral cartilage and scroll region. Zone 2 LWI occurs at the level of the ala and is more akin to classically described external valve collapse.2 Zone 1 LWI often is idiopathic and sometimes, because of senescence, mild to moderate trauma or heredity, whereas zone 2 LWI often is iatrogenic.1 In each zone, LWI is graded according to the distance the nasal wall moves toward the septum (grade 0 is no movement, grade 1 is 1%-33%, grade 2 is 34%-66%, and grade 3 is 67%-100%).3

Figure 1. Zones of Lateral Nasal Wall Insufficiency.

Zone 1 (upper zone) corresponds to dynamic internal nasal valve collapse. Zone 2 (lower zone) corresponds to classic external valve collapse. Reprinted with permission from OceanSide Publications.2

We have validated this grading system2 and have applied it to all patients presenting to our clinic. This system, paired with the Nasal Obstruction Symptom Evaluation (NOSE) score (range, 0-100, with 100 showing the most severe nasal obstruction), has provided us with a valuable objective assessment for all patients at each clinic visit.4 The NOSE score is a patient-reported outcome measure developed to assess nasal obstruction and for which the senior author has previously developed a severity scale (range, 0-100, with 100 indicating the worst nasal obstruction symptoms).4,5 Several surgical techniques address LWI, such as the lateral crural strut graft (LCSG), the alar batten graft, and the alar rim graft; each technique has been extensively examined and discussed in the literature.6,7,8 In this article, we examine the long-term objectives and patient-reported outcomes of this individualized treatment strategy for LWI repair to enable surgeons to formulate simplified treatment recommendations.

Methods

A retrospective review was performed for all patients who underwent septorhinoplasty to repair LWI (n = 44) at our center between February 1, 2014, and May 31, 2016. An age- and sex-matched group of patients who underwent cosmetic septorhinoplasty without LWI repair (n = 44) was also selected. Cosmetic patients did not report any nasal obstruction prior to surgery. All surgical procedures and postoperative examinations were performed by the senior author. The Stanford University institutional review board approved this study and waived patient informed consent and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) authorization because consent was not necessary for a retrospective medical record review.

Patients in both groups completed a NOSE questionnaire before surgery and at all subsequent postoperative visits. All patients were examined for LWI before surgery and during postoperative visits, and LWI grading was documented in the clinic visit notes. The data reviewed included demographic characteristics; LWI grades; NOSE scores; and details of operative reports, including the type of surgical technique used for every patient. Paired, 2-tailed t tests were performed to compare LWI grades and NOSE scores at baseline and subsequent visits of patients in each group. Independent sample t tests were used to compare the 2 groups. Two-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Pearson correlation coefficients were used to evaluate correlations between NOSE scores and LWI grades.

Results

The study included 44 patients with nasal obstruction and LWI who underwent LWI repair (group 1) and 44 age- and sex-matched controls who did not have LWI repair (group 2). The mean (SD) age of patients was 46 (16) years in group 1 and 41 (12) years in group 2, and each group had 8 men and 36 women. Data on patient demographics, history of previous nasal surgery, location of LWI, and mean NOSE score are shown in Table 1. The 2 groups are comparable in all aspects except for the presence of LWI in both zones 1 and 2 and NOSE scores. The mean (SD) NOSE score in group 1 was 69.4 (22.0), which is categorized as severe obstruction. In group 1, LWI was more frequent in zone 1 (39 of 44 patients [89%]) than in zone 2 (14 of 44 patients [32%]). Table 2 lists surgical procedures performed in our cohort. The groups are different in all techniques except for septoplasty, alar rim graft, and alar batten graft.

Table 1. Data on Patient Demographics, Nasal Surgery History, LWI Location, and Mean NOSE Score.

| Variable | Patients, No. (%) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (n = 44)a |

Group 2 (n = 44)b |

||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 46 (16) | 41 (12) | .10 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 8 (18) | 8 (18) | >.99 |

| Female | 36 (82) | 36 (82) | |

| Nasal surgery | NA | NA | |

| Primary | 30 (68) | 31 (70) | .82 |

| Revision | 14 (32) | 13 (29) | |

| LWI Location | |||

| Zone 1 | |||

| None | 5 (11.4) | 37 (84.1) | <.001 |

| Grade 1 | 11 (25.0) | 5 (11.4) | |

| Grade 2 | 23 (52.3) | 0 | |

| Grade 3 | 5 (11.4) | 0 | |

| Zone 2 | |||

| None | 30 (68.2) | 41 (93.2) | .004 |

| Grade 1 | 4 (9.1) | 0 | |

| Grade 2 | 7 (15.9) | 1 (2.3) | |

| Grade 3 | 3 (6.8) | 0 | |

| NOSE score, mean (SD) | 69.4 (22.0) | 20.5 (20.8) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: LWI, lateral wall insufficiency; NOSE, Nasal Obstruction Symptom Evaluation.

Patients in group 1 underwent septorhinoplasty to repair LWI.

Patients in group 2 underwent cosmetic septorhinoplasty without LWI repair.

Table 2. Surgical Procedures Performed in Our Cohort.

| Procedure | Patients, No. (%) | P Value for χ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (n = 44)a |

Group 2 (n = 44)b |

||

| Cosmetic rhinoplasty | 11 (25) | 44 (100) | <.001 |

| Septoplasty | 31 (70) | 22 (50) | .05 |

| Anterior septal reconstruction | 12 (27) | 3 (7) | <.001 |

| Turbinate reduction | 32 (73) | 6 (14) | <.001 |

| Osteotomy | 6 (14) | 19 (43) | .002 |

| Autospreader | 5 (11) | 18 (41) | .002 |

| Graft | |||

| Spreader | 23 (52) | 8 (18) | .001 |

| Lateral crural strut | 38 (86) | 10 (23) | <.001 |

| Alar rim | 4 (9) | 4 (9) | >.99 |

| Alar batten | 3 (7) | 0 | .08 |

Patients in group 1 underwent septorhinoplasty to repair lateral wall insufficiency.

Patients in group 2 underwent cosmetic septorhinoplasty without lateral wall insufficiency repair.

The change in LWI grades for groups and zones is shown in Figure 2. In group 1, the grades significantly decreased in zone 1 from a preoperative grade of 1.636 to a grade of 0.163 at 3 months (−1.2; 95% CI, −0.6 to −1.8; P < .001) and 0.389 at 12 months (−1.5; 95% CI, −1.2 to −1.8; P = .001), and the grades also decreased in zone 2 from a preoperative grade of 0.613 to a grade of 0.093 at 3 months (−0.5; 95% CI, −0.2 to −0.8; P = .001) and 0.167 at 12 months (−0.5; 95% CI, −0.1 to −0.8; P = .046). In contrast, LWI grades in group 2 were low, and there was no significant difference between baseline preoperative and long-term follow-up grades (from 0.119 to 0.042 in zone 1 [−0.06; 95% CI, −0.01 to −0.1] and from 0.048 to 0 in zone 2 [−0.04; 95% CI, −0.01 to −0.4]; P > .05), except for a slight decrease in zone 1 at 3 months (0.289; P = .04]) that did not persist at 12 months (0.042). After surgery, a significant difference in LWI grades was no longer observed between groups, and this result persisted at long-term follow-up.

Figure 2. Comparison of Lateral Wall Insufficiency (LWI) Grades Between Groups Over Time (t Test).

The change in NOSE scores for each group is shown in Figure 3. The NOSE scores decreased in group 1 from a preoperative score of 69.4 to a score of 24.1 at 3 months (−45.3; 95% CI, −35.7 to −54.3; P < .001) and a score of 24.7 at 12 months (−44.7; 95% CI, −28.9 to −49.9; P < .001) and decreased in group 2 from a preoperative score of 20.5 to a score of 11.4 at 3 months (−9.1; 95% CI, −1.3 to −16.0; P = .09) and a score of 6 at 12 months (−14.5; 95% CI, −2.7 to −18.5; P = .02). Figure 3 shows that the NOSE scores between groups are different at all time periods, with group 2 demonstrating statistically lower scores than that of group 1.

Figure 3. Comparison of Nasal Obstruction Symptom Evaluation (NOSE) Scores Between Groups Over Time (t Test).

The NOSE score has a range from 0 to 100, with 100 indicating the worst nasal obstruction symptoms.

A strong positive correlation was found between zone 1 LWI grades and NOSE scores in the preoperative (R = 0.68) and 12-month postoperative periods (R = 0.6).9 There was a moderate positive correlation between zone 2 LWI grades and NOSE scores in both preoperative (R = 0.42) and 12-month postoperative periods (R = 0.58). Only 1 case (2%) in group 1 required revision, a unilateral LCSG placement 6 months after initial surgery for persistent symptoms.

Discussion

We found objective and subjective improvements in the nasal airway after LWI repair. The LWI grades significantly improved after surgery in both zones and remained stable at long-term follow-up. Postoperative LWI grades between cases and controls did not show any significant difference, which implies successful long-term repair of LWI.

NOSE scores significantly decreased in long-term follow-up, a result similar to that in other studies.10 Although NOSE scores at long-term follow-up for both groups were still statistically different, these scores place the patients in group 1 in a mild obstruction category; these scores are within the range found in the general population, as demonstrated in a previous study.11

The most common method used to treat LWI is LCSG placement, and we use it in patients with zone 1 LWI, whether with or without zone 2 LWI. Described by Gunter and Friedman,6 this technique is used for cosmetic purposes such as the boxy nasal tip, malpositioned lateral crura, alar rim retraction, and concave lateral crura. Of the 88 patients who underwent LCSG placement in the Gunter and Friedman cohort, only 1 underwent revision LCSG, which is similar to the rate of revision in our study.

In another study, Barham et al12 compared LCSG with cephalic turn-in of the lateral crura to correct external valve dysfunction. They concluded that both techniques were effective in improving patient-reported outcomes and nasal peak inspiratory flow. In their LCSG group, the NOSE score significantly improved (−31.21; P < .001), which is similar to our results (−45; P < .001).

Alar rim graft is another method used in our cohort to correct LWI. We use it mainly for patients who present with zone 2 LWI, whether zone 1 is involved or not. This technique was introduced by Troell et al,13 who reported a 94.9% improvement of nasal obstruction resulting from nasal valve collapse repair. Guyuron14 and Rohrich et al15 further evaluated the technique and achieved varying success rates. The major indications for alar rim graft placement are zone 2 LWI, prevention or correction of the alar concavity, advancing of the ala caudally, widening of the nostril, and elongation of the short nostril.16

Spreader flaps (autospreader) were used in 41% of our control group. We routinely perform this procedure with hump takedown to maintain the width of midvault to counter the Bernoulli effect17 and preserve the nasal airway. Our control group (group 2) shows that consideration of the functional aspects of rhinoplasty during cosmetic surgery can potentially prevent nasal obstruction in the postoperative period and can actually decrease NOSE scores.

Our results confirm that the LWI grading system is well correlated with the NOSE score. This finding is in contrast to findings of previous studies, which used internal and external nasal valve collapse terms to evaluate correlations with NOSE scores.18

The strength of the present study is the use of both the physician-derived, validated LWI grading system as an objective outcome measure tool and the well-described disease-specific NOSE score as a patient-derived grading system. Previously used objective tools, such as acoustic rhinometry and nasal peak inspiratory flow, often do not correlate with patient-reported outcome measures.19 In addition, given the dynamic nature of the airway in patients with weak lateral nasal walls, static measures of the nasal airway may not give an accurate representation of airway status.3

Limitations

The limitations of this study are its retrospective nature; the examiner (S. P. Most) not being blinded to the surgical procedure performed; the use of spreader grafts in group 1; and LWI scoring encompassing a percentage of collapse, which can introduce some bias. However, the LWI grading system was previously validated with good reliability.2

Conclusions

Lateral wall insufficiency can be successfully repaired using LCSG for zone 1 insufficiency and alar rim graft for zone 2 insufficiency and can yield excellent objective and subjective outcomes as measured by the LWI grading system and the NOSE questionnaire. These outcomes demonstrate that patients with LWI can be restored to the functional level of patients without nasal obstruction. Moreover, the LWI grading system correlates well with NOSE scores and is a reliable indicator of subjective improvement after surgery.

References

- 1.Most SP. Trends in functional rhinoplasty. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2008;10(6):410-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsao GJ, Fijalkowski N, Most SP. Validation of a grading system for lateral nasal wall insufficiency. Allergy Rhinol (Providence). 2013;4(2):e66-e68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Most SP. Comparing methods for repair of the external valve: one more step toward a unified view of lateral wall insufficiency. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2015;17(5):345-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart MG, Witsell DL, Smith TL, Weaver EM, Yueh B, Hannley MT. Development and validation of the Nasal Obstruction Symptom Evaluation (NOSE) scale. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130(2):157-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lipan MJ, Most SP. Development of a severity classification system for subjective nasal obstruction. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2013;15(5):358-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gunter JP, Friedman RM. Lateral crural strut graft: technique and clinical applications in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99(4):943-952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cervelli V, Spallone D, Bottini JD, et al. Alar batten cartilage graft: treatment of internal and external nasal valve collapse. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2009;33(4):625-634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boahene KDO, Hilger PA. Alar rim grafting in rhinoplasty: indications, technique, and outcomes. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2009;11(5):285-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans JD. Straightforward Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole Publishing Co; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindsay RW. Disease-specific quality of life outcomes in functional rhinoplasty. Laryngoscope. 2012;122(7):1480-1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rhee JS, Sullivan CD, Frank DO, Kimbell JS, Garcia GJM. A systematic review of patient-reported nasal obstruction scores: defining normative and symptomatic ranges in surgical patients. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2014;16(3):219-225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barham HP, Knisely A, Christensen J, Sacks R, Marcells GN, Harvey RJ. Costal cartilage lateral crural strut graft vs cephalic crural turn-in for correction of external valve dysfunction. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2015;17(5):340-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Troell RJ, Powell NB, Riley RW, Li KK. Evaluation of a new procedure for nasal alar rim and valve collapse: nasal alar rim reconstruction. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122(2):204-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guyuron B. Alar rim deformities. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107(3):856-863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rohrich RJ, Raniere J Jr, Ha RY. The alar contour graft: correction and prevention of alar rim deformities in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109(7):2495-2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guyuron B, Bigdeli Y, Sajjadian A. Dynamics of the alar rim graft. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135(4):981-986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teymoortash A, Fasunla JA, Sazgar AA. The value of spreader grafts in rhinoplasty: a critical review. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;269(5):1411-1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leitzen KP, Brietzke SE, Lindsay RW. Correlation between nasal anatomy and objective obstructive sleep apnea severity. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;150(2):325-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lam DJ, James KT, Weaver EM. Comparison of anatomic, physiological, and subjective measures of the nasal airway. Am J Rhinol. 2006;20(5):463-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]