Abstract

Since its initial emergence in 1976 in northern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Ebola virus (EBOV) has been a global health concern due to its virulence in humans, the mystery surrounding the identity of its host reservoir and the unpredictable nature of Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreaks. Early after the first clinical descriptions of a disease resembling a ‘septic-shock-like syndrome’, with coagulation abnormalities and multi-system organ failure, researchers began to evaluate the role of the host immune response in EVD pathophysiology. In this review, we summarize how data gathered during the last 40 years in the laboratory as well as in the field have provided insight into EBOV immunity. From molecular mechanisms involved in EBOV recognition in infected cells, to antigen processing and adaptive immune responses, we discuss current knowledge on the main immune barriers of infection as well as outstanding research questions.

Introduction

Ebola virus (EBOV, species Zaire ebolavirus) is a non-segmented negative-sense RNA virus belonging to the Filoviridae family within the order Mononegavirales. The EBOV genome harbors seven genes that encode at least eight proteins [1]. EBOV has been a mystery for laymen and scientists alike, since its high virulence and origin have been difficult to explain. Initial reports described a case-fatality ratio (CFR) of up to 90% in humans and virtually 100% in experimentally-infected non-human primates (NHP), and laboratories around the world have devoted efforts during the last forty years to defining the molecular mechanisms responsible for EBOV disease (EVD) pathophysiology.

Early studies during and after the Yambuku outbreak reported evidence of necrosis in liver biopsies as well as disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) in patients who died from EVD [2,3]. Extensive necrosis in lymphoid and non-lymphoid tissues as well as DIC was shortly after observed in NHP infected with EBOV via parenteral inoculation [4,5]. As the NHP evolved as the ‘gold-standard’ filovirus infection model, many of the initial features of EBOV immunology were described in this model, including the coincident detection of virus-specific antibodies and viral clearance [6], EBOV-associated neutrophilia and lymphopenia, and the first notion that immune-based mechanisms could be responsible for endothelial dysfunction [7]. Later on, the NHP model also served to identify macrophages and dendritic-like cells as putative primary targets for EBOV infection [8–10]. With the confirmation of EBOV-induced lymphopenia and lymphocyte apoptosis in humans [11] and the identification of viral protein (VP) 35 and VP24 as type I interferon (IFN-I) antagonists (reviewed in [12]), the prevailing model for many years has been that EBOV infection is associated with strong immune suppression. However, the research community recognized that this model did not reconcile well with the overwhelming inflammation associated with fatal ebolavirus infection [13–15]. Here we discuss how our understanding of EBOV-induced immune responses has evolved throughout the years. In particular we will focus on cell-intrinsic, innate and adaptive EBOV immunity and will identify still-unresolved research questions.

Innate barriers to EBOV infection

All animal species, including humans, are equipped with natural barriers to infection, which include cellular sensors, innate cytokines and innate immune cells among others. Here we briefly summarize innate immune barriers to EBOV infection in humans and animal models of infection.

Cellular checkpoints — attachment factors and EBOV receptor

Permissiveness to EBOV infection is rather rare in the animal kingdom. Only a few species are susceptible to infection, unfortunately this includes humans. Why humans are so vulnerable to EVD in contrast to, for example, rodents is not well understood. However, intrinsic barriers that prevent or inhibit EBOV infection at different steps of the viral replication cycle have been identified. Attachment of EBOV particles to the cell surface is mediated by binding of the highly glycosylated EBOV glycoprotein (GP) to two distinct groups of carbohydrate-binding cellular surface proteins, C-type lectin receptors and glycosaminoglycans (reviewed in [16]). In addition to carbohydrate binding proteins, EBOV particles interact with surface proteins that directly or indirectly bind to phosphatidylserine, including TIM and TAM receptors. Thus, attachment to the target cell is a promiscuous process, that is only partially blocked by knocking down individual attachment factors [16]. After internalization by macropinocytosis [17], EBOV engages its receptor in the endosome, the cholesterol transporter Niemann-Pick C1 (NPC1) protein [18,19]. In contrast to the various surface attachment factors that are involved in EBOV entry, NPC1 is indispensable for EBOV infection. Thus, cells derived from patients with homozygous mutations in NPC1 and NPC1 knockout mice are resistant to EBOV infection [18,20]. Interestingly, sequence polymorphism of the npc1 locus in different animal species affects NPC1-GP interaction, thus preventing EBOV entry in a species-specific manner as shown for the NPC1 proteins of Russell’s vipers, King cobras and African straw-colored fruit bats [21•,22].

Role of antigen presenting cells — immunity versus virus dissemination

EBOV has a broad cell tropism including endothelial and epithelial cells, hepatocytes, fibroblasts and some types of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) such as macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs) (reviewed in [23]). The preference of EBOV to infect APCs and, in particular, DCs has important implications for the host immune response. DCs provide a bridge between innate and adaptive immunity as they are necessary to process pathogen material into defined epitopes and present them to cognate naïve T cells [24]. Considering that most of the human population is immunologically naïve to EBOV [25–28], proper APC function during EVD is essential to initiate virus-specific responses.

In an early study that evaluated the susceptibility of NHP to aerosolized EBOV, alveolar macrophages, an important subset of respiratory APCs, were shown to contain EBOV antigen [8]. Later on, using a combination of immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy techniques, another type of APCs, dendritic cells (DCs) (or rather, ‘DC-like’ cells), were shown to contain EBOV nucleocapsids, which strongly suggested that these cells supported EBOV replication in vivo [9,10]. Preferential infection of macrophages was also observed in other filovirus infections, including a patient fatally infected with Marburg virus (MARV) [29], a chimpanzee fatally infected with Taï Forest virus (TAFV) [30] and NHPs infected with Reston virus (RESTV) [31] (Figure 1).

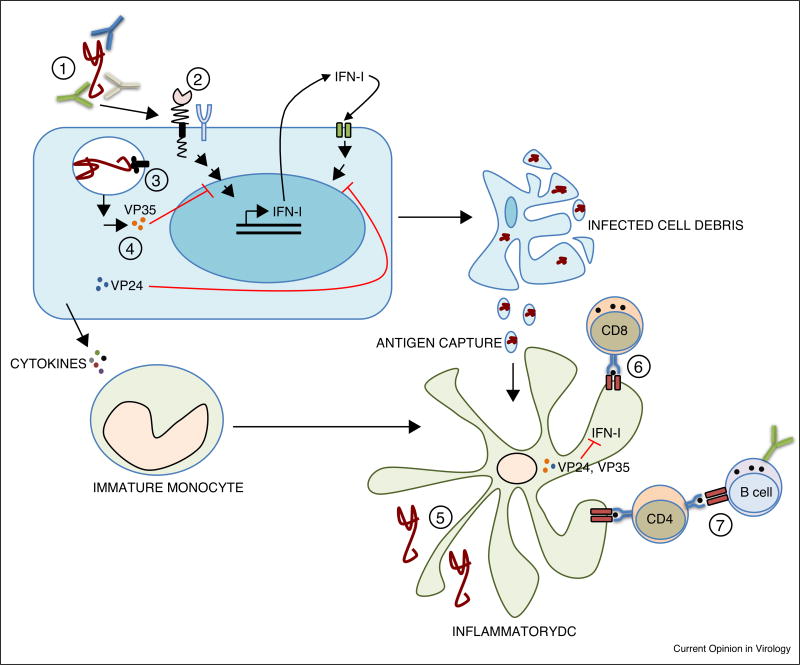

Figure 1.

Barriers to EBOV infection. (1) Neutralizing Abs and Ab-mediated functions; (2) Attachment factors such as C-type lectin receptors allow EBOV binding to the membrane of target cells. (3) EBOV enters through macropinocytosis and binds its cellular receptor, the cholesterol transporter Niemann-Pick C1 (NPC1) in the endosome; (4) In infected cells, viral proteins VP35 and VP24 play an important role targeting the type I IFN response both at the production and signaling levels; (5) EBOV infects discrete DC subsets (inflammatory DCs derived from monocytes) which also capture cell debris from other infected cells; (6) DCs provide a bridge between innate and adaptive immunity by priming of EBOV-specific CD8 T cells; (7) CD4 T cell mediated help is necessary for activation of the humoral immune response and anti-EBOV antibody production.

One major limitation in interpreting the results of these initial studies is that it is difficult to morphologically distinguish macrophages from DCs, in particular inflammatory DCs derived from monocytes, without the aid of flow cytometry-based immunophenotyping. Moreover, due to the phagocytic capacity of APCs, it is also challenging to discriminate between infection and antigen-capturing (i.e. engulfment of infected-cell debris). One strategy to discriminate between infection and antigen capturing is co-labeling with antibodies against internal proteins and surface glycoproteins (as readout of active virus shedding) [32]. In NHP and guinea pigs infected with EBOV, VP40, the viral matrix protein, was readily stained in tissue macrophages while only some subpopulations showed evidence of surface GP [33]. Following this strategy, it was recently observed that intranasal inoculation of EBOV allowed detection of surface GP in murine alveolar macrophages and DCs but not in immature monocytes and neutrophils. Further characterization of the infected DC subsets showed that DC-SIGN-expressing inflammatory and resident DCs were infected with EBOV in the lung as well as lung-draining lymph nodes. Conversely, DC subsets expressing langerin did not stain for GP suggesting that these cells may be spared from infection [34•]. These results raise two important questions: Do infected DC-SIGN+ DCs participate in EBOV dissemination? And, since langerin+ DCs are highly specialized in the activation of CD8 T cells, what role do these cells play in bridging innate and adaptive immune responses to EBOV? [35,36] Interestingly, langerin+ DCs might be resistant to fusion of enveloped viruses including HIV and influenza virus [37,38]. These findings suggest a division of labor by which, while DC-SIGN+ DCs would be directly infected with EBOV, langerin+ DCs would specialize in capturing debris from infected cells to recirculate antigens for presentation via MHC class I; the so-called cross-presentation pathway. Whether this is the case during EBOV infection is an important research question.

Macrophages might also play an important role in the induction of the strong inflammatory response observed in EBOV infection. Although innate responses are suppressed in many cell types when infected with EBOV (see below), macrophages are remarkable exceptions. In these cells, EBOV infection elicits a proinflammatory response including strong upregulation of IFN-I signaling pathways [39,40,41•,42,43]. Activation of monocyte-derived macrophages occurs at a very early stage of infection and is mediated by the viral surface protein GP through toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) [44–46]. Activation of TLR4, a classic sensor for bacterial infections, is common to several viral proteins such as Dengue NS1, HBsAg and RSV F [47–49], but its consequences on antiviral immune responses are not well understood. GP-mediated activation of TLR4 could skew downstream T-cell responses away from the typical Th1 response seen during most viral infections [50•,51••] toward at Th2 phenotype [52], which could influence patient outcome; alternatively the GP-TLR4 interaction might also play a role in the induction of T-cell death during EBOV infection [53]. Of note, T cells are not infected by EBOV [54], but EBOV particles seem to be able to bind to T cells and trigger the activation of an inflammatory response, including TLR4 and Tim-1 signaling [53,55].

Approaches to suppress the inflammatory response in EBOV infection show promising results [56] This includes the use of TLR4 antagonists which have been shown to dampen the proinflammatory response during EBOV infection in primary human macrophages and in infected mice, opening up novel supportive treatment options for EVD [57,58].

Interferon-replication barriers and viral counter attack

The interferon system (IFN) is a major innate barrier for virus infection as well as a chief driver of APC function [59,60]. As many other viruses, EBOV is sensitive to interferon (IFN). Pre-treatment of cells in vitro with IFN-I or type II IFN (IFN-II) significantly reduces EBOV replication [61–63]. Although IFN-I treatment of EBOV-infected nonhuman primates did not protect the animals from lethal disease [64] it led to prolonged survival in one study [65]. Protection was achieved when IFN was administered in combination with monoclonal antibodies [66]. Mice treated with IFNg survived an otherwise lethal EBOV infection, supporting the in vitro data [62•]. Among the identified antiviral interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) that block EBOV infection are IFN-induced transmembrane (IFITM) proteins and Zinc finger antiviral protein (ZAP) (for review see [67]).

Not surprisingly, EBOV has evolved strategies to counteract the IFN response. Out of seven structural proteins, at least three, GP, VP35 and VP24, are involved in dampening the innate immune response with VP35 and VP24 being the central players [67]. VP35, a cofactor of the viral polymerase, blocks RIG I-mediated antiviral responses including IFN-I induction, while VP24, a protein involved in nucleocapsid formation, interferes with IFN-I and IFN-II signaling (reviewed in [12]). Work with recombinant EBOV expressing mutant VP35 and/or VP24 shed some light on the role of these proteins as virulence factors. In vitro, both proteins interfere with the maturation of infected monocyte-derived dendritic cells (DC), potentially suppressing T cell responses [68,69••]. Infection with recombinant EBOV containing mutations in VP35’s IFN-inhibitory domain not only led to increased activation of antiviral pathways and reduced viral replication in cell culture but also to complete attenuation in a mouse model of EBOV infection [70–73]. This shows that VP35-mediated dampening of the innate immune response is critical for pathogenesis. Interestingly, adaptation of EBOV to guinea pigs or mice results in adaptive mutations in VP24, while VP35 is not affected [74,75]. However, since wild-type and rodent-adapted VP24 proteins block IFN signaling in both human and rodent cells equally well [76,77], it is questionable if the ability to block innate immune responses is a determinate of EBOV permissiveness.

Given the inhibitory effects of IFNs on EBOV replication and the requirement of the virus to block IFN responses for optimal replication, it came as a surprise that IFN signaling pathways were more strongly upregulated in patients, who succumbed to EBOV disease, than in those who survived the infection [78•,79,80]. This might be partially explained by the activation of immune-relevant cells through TLR4 or other physiological events that cannot be reproduced by in vitro studies. Alternatively, since patients generally arrive for care well into the course of their illness, the elevated IFN seen in fatal cases may be a direct reflection of uncontrolled viral loads stimulating an exaggerated IFN response.

Adaptive immunity against Ebola virus

Acute infection — mechanisms of virus clearance

Early work on EVD in humans demonstrated decreased numbers of total and HLA-DR+ CD8 T cells as well as increased levels of Fas, Fas ligand and associated lymphocyte apoptosis in patients with fatal outcomes [11,81,82]. These data, along with the finding of persistently elevated viral loads in patients who succumb to disease [83], suggested a role for T cells in control of viral replication and clearance. In fact, despite T-cell lymphopenia, CD8 T cells proliferated, expressed activation markers and adoptive transfer of CD8 T cells from moribund mice could protect 100% of naive mice from EBOV challenge [84]. Studies also indicated that lymphocyte apoptosis in itself was likely not a determinate of outcome since Bcl-2 KO mice still died despite a significant decrease in lymphocyte apoptosis [85]. Finally, T-cell depletion in infected mice and NHP resulted in loss of protection and increased virus replication and dissemination [10,34•,86].

There is substantial T-cell activation during acute infection in humans, however, the frequency of CD8 T cells expressing inhibitory markers are elevated in patients who succumb to disease, suggesting that T cells play a functional role in EVD outcome [87••]. Nevertheless, while a high magnitude of T cell activation has been demonstrated in acute EVD, the specificity of this response namely, virus-specific versus bystander T-cell activation, has yet to be reported.

Individuals who succumb to disease often do so with either very low or no EBOV-specific antibodies [11], and viral loads are often already declining before detection of EBOV-specific IgG [83,88], suggesting that during natural infection, the humoral response may play a minimal role in recovery. While EBOV-specific IgM is present in most individuals by 10 days post symptom onset, it is not until almost three weeks after symptom onset that most patients are positive for EBOV-specific IgG [89]. There is limited data on the development of neutralizing antibodies during acute infection and survivors do not have significant neutralizing titers until well into convalescence [90]. Finally, in mouse models of EVD, B cells are completely dispensable for survival from infection [86]. Despite the lackluster evidence for a role of the native virus-specific IgG response in survival during natural infection, there is a large amount of data suggesting that specific combinations of passively transferred antibodies, even when provided during acute infection, can improve clinical outcomes [91].

Convalescence and beyond — waning immunity and hidden antigens

Following recovery from acute EVD, both virus-specific T-cell responses as well as virus-specific humoral responses can last at least up to 10 years [92]. However, the magnitude of these responses wanes over time with only 29% having neutralizing antibodies at the 10-year time point [93]. The T-cell responses of this same patient population demonstrated long lived EBOV-specific effector CD4 T cells, but only in those survivors that also had EBOV neutralizing activity [94]. The authors were not able to detect significant CD8 T cell responses in these long-term survivors. Whether this is a technical challenge or an indication of a lack of persistence of CD8 T cell memory remains to be seen. In repatriated EVD survivors, virus-specific CD8 T cells are still detectable, albeit at low frequencies at least out to 18 months post-discharge (Rama Akondy, personal communication).

Significant clinical sequelae following EVD have been noted since the first outbreaks [89,95–97]. The prolonged sequelae of disease could be secondary to immune phenomena rather than virally mediated [98], but virus persistence has been observed, specifically in sites that are classically thought of as immune privileged, including the brain, eye and testicle (semen) [78•,99••,100••]. It seems reasonable to conclude that the virus is able to persist in these locations and evade immune surveillance because these sites are, by definition, able to tolerate foreign antigens [101]. However, it is clear that there can be a break in this tolerance of foreign viral antigen since inflammation was noted in both the eye and the brain in two patients with clinical recurrence of EVD in these locations [99••,100••]. Furthermore in the NHP model, investigators were able to demonstrate that local mononuclear phagocytic cells in these locations are the sties of virus persistence [102•]. When and how virus reactivation and immune recognition occurs in these sites remains a mystery.

Active or passive vaccination against EBOV — the need for correlates of immunity

Immunity that contributes to survival during natural infection may not be the same as immunity that can protect following active or passive vaccination. In passive vaccination, only the humoral component is at work and this can be protective when given pre-exposure and can rescue from death when given well into the disease [91]. These antibodies appear to work not only by direct neutralization but also by engaging effector functions such as ADCC [103].

A wealth of literature exists on EBOV vaccines in animal models [104], so we will focus on correlates of immunity in vaccines that have been trialed in humans and NHP’s. Using a rAd5 EBOVGP-based vaccine, it was clearly demonstrated that protection from challenge was mediated by CD8 T cells in NHPs [105]. In contrast, using an rVSV EBOVGP-based vaccine, investigators suggested that antibodies were the correlate of protection since CD4 depletion prior to vaccination but not at time of challenge led to loss of vaccine-mediated protection [106]. Therefore the mechanistic correlate of protection can be different depending on the vaccine platform chosen to deliver the antigen.

Multiple reports of human clinical trials focus on two promising vaccine platforms, rVSV or rAdenovirus (either rAd5 or rChAd3) to deliver the viral GP, and all show induction of GP-specific humoral immunity using a variety of different assays [107–118]. The only human EBOV vaccine study to date that evaluated efficacy used the rVSV vectored GP [119]. Unfortunately, while some of the rAdenovirus vectored vaccine studies examined T cell responses, there are very little data about T cell responses in any of the rVSV studies, and all studies utilized different types of assays for quantitation of immune responses, making comparisons inappropriate. A recently published study evaluated both ChAd3-EBO-Z and rVSVG-ZEOBV-GP side-by-side as compared to placebo, and all vaccinated individuals developed robust GP-specific antibody responses [117]. However, despite all of these trials in humans, no immunologic correlate of protection (either mechanistic or non-mechanistic) has been defined; a clear gap that needs to be addressed.

Summary and perspective

Many studies during the last forty years have provided insight into the filovirus host-range, the mechanisms of infection and virus antagonism of the host response, and the role of both arms of the adaptive immune response in virus clearance. There are however many outstanding open questions. For example, it will be important in the near future to reconcile the in vitro findings regarding EBOV-mediated type I IFN antagonism with the observation that fatal EVD is associated with higher production of IFN. To address this question, it will be necessary to establish in vivo platforms that permit a dissection of the interaction between EBOV proteins and the IFN system early during infection. Along the same lines, it is of great interest to determine the mechanisms by which EBOV disseminates from the initial points of infection (presumably skin and mucosae) to the body. Studies in animal models will be helpful to determine the molecular mechanisms responsible for the observed dysregulation of T-cell homeostasis in humans as well as to compare the relative contribution of antibody neutralization and Fc-mediated functions to virus clearance. One important challenge ahead is to convert this knowledge into antiviral strategies and highly needed post-exposure medical countermeasures.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the German Center of Infection Research (DZIF-TTU01.702 to C.M.-F.), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (K08 AI119448 to A.K.M, R21 AI082954 to E.M), a Burroughs Wellcome CAMS (1013362.01 to A.K.M), and the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (HDTRA1-14-1-0016, PI G. Palacios to E.M.).

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Volchkov VE, Volchkova VA, Muhlberger E, Kolesnikova LV, Weik M, Dolnik O, Klenk HD. Recovery of infectious Ebola virus from complementary DNA: RNA editing of the GP gene and viral cytotoxicity. Science. 2001;291:1965–1969. doi: 10.1126/science.1057269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ebola haemorrhagic fever in Zaire, 1976. Bull World Health Organ. 1978;56:271–293. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson KM, Lange JV, Webb PA, Murphy FA. Isolation and partial characterisation of a new virus causing acute haemorrhagic fever in Zaire. Lancet. 1977;1:569–571. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)92000-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baskerville A, Bowen ET, Platt GS, McArdell LB, Simpson DI. The pathology of experimental Ebola virus infection in monkeys. J Pathol. 1978;125:131–138. doi: 10.1002/path.1711250303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowen ET, Platt GS, Simpson DI, McArdell LB, Raymond RT. Ebola haemorrhagic fever: experimental infection of monkeys. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1978;72:188–191. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(78)90058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisher-Hoch SP, Perez-Oronoz GI, Jackson EL, Hermann LM, Brown BG. Filovirus clearance in non-human primates. Lancet. 1992;340:451–453. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91770-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fisher-Hoch SP, Platt GS, Neild GH, Southee T, Baskerville A, Raymond RT, Lloyd G, Simpson DI. Pathophysiology of shock and hemorrhage in a fulminating viral infection (Ebola) J Infect Dis. 1985;152:887–894. doi: 10.1093/infdis/152.5.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson E, Jaax N, White J, Jahrling P. Lethal experimental infections of rhesus monkeys by aerosolized Ebola virus. Int J Exp Pathol. 1995;76:227–236. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ryabchikova EI, Kolesnikova LV, Luchko SV. An analysis of features of pathogenesis in two animal models of Ebola virus infection. J Infect Dis. 1999;179(Suppl. 1):S199–S202. doi: 10.1086/514293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geisbert TW, Hensley LE, Larsen T, Young HA, Reed DS, Geisbert JB, Scott DP, Kagan E, Jahrling PB, Davis KJ. Pathogenesis of Ebola hemorrhagic fever in cynomolgus macaques: evidence that dendritic cells are early and sustained targets of infection. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:2347–2370. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63591-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baize S, Leroy EM, Georges-Courbot MC, Capron M, Lansoud-Soukate J, Debré P, Fisher-Hoch SP, McCormick JB, Georges AJ. Defective humoral responses and extensive intravascular apoptosis are associated with fatal outcome in Ebola virus-infected patients. Nat Med. 1999;5:423–426. doi: 10.1038/7422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Messaoudi I, Amarasinghe GK, Basler CF. Filovirus pathogenesis and immune evasion: insights from Ebola virus and Marburg virus. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015;13:663–676. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bray M, Geisbert TW. Ebola virus: the role of macrophages and dendritic cells in the pathogenesis of Ebola hemorrhagic fever. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;37:1560–1566. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McElroy AK, Erickson BR, Flietstra TD, Rollin PE, Nichol ST, Towner JS, Spiropoulou CF. Ebola hemorrhagic fever: novel biomarker correlates of clinical outcome. J Infect Dis. 2014;210:558–566. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hutchinson KL, Rollin PE. Cytokine and chemokine expression in humans infected with Sudan Ebola virus. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(Suppl. 2):S357–S363. doi: 10.1086/520611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davey RA, Shtanko O, Anantpadma M, Sakurai Y, Chandran K, Maury W. Mechanisms of filovirus entry. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2017;26:1–30. doi: 10.1007/82_2017_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saeed MF, Kolokoltsov AA, Albrecht T, Davey RA. Cellular entry of ebola virus involves uptake by a macropinocytosis-like mechanism and subsequent trafficking through early and late endosomes. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001110. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carette JE, Raaben M, Wong AC, Herbert AS, Obernosterer G, Mulherkar N, Kuehne AI, Kranzusch PJ, Griffin AM, Ruthel G, et al. Ebola virus entry requires the cholesterol transporter Niemann-Pick C1. Nature. 2011;477:340–343. doi: 10.1038/nature10348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Côté M, Misasi J, Ren T, Bruchez A, Lee K, Filone CM, Hensley L, Li Q, Ory D, Chandran K, et al. Small molecule inhibitors reveal Niemann-Pick C1 is essential for Ebola virus infection. Nature. 2011;477:344–348. doi: 10.1038/nature10380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herbert AS, Davidson C, Kuehne AI, Bakken R, Braigen SZ, Gunn KE, Whelan SP, Brummelkamp TR, Twenhafel NA, Chandran K, et al. Niemann-pick c1 is essential for ebolavirus replication and pathogenesis in vivo. MBio. 2015;6:e00565–e615. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00565-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21•.Ng M, Ndungo E, Kaczmarek ME, Herbert AS, Binger T, Kuehne AI, Jangra RK, Hawkins JA, Gifford RJ, Biswas R, et al. Filovirus receptor NPC1 contributes to species-specific patterns of ebolavirus susceptibility in bats. Elife. 2015;4:RRN1212. doi: 10.7554/eLife.11785. This paper analyzes the effect of single aminoacid mutations on the host range of filoviruses within bat species. It provides experimental evidence that NPC1 partially determines filovirus infectivity. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ndungo E, Herbert AS, Raaben M, Obernosterer G, Biswas R, Miller EH, Wirchnianski AS, Carette JE, Brummelkamp TR, Whelan SP, et al. A single residue in Ebola virus receptor NPC1 influences cellular host range in reptiles. mSphere. 2016;1:e00007–e16. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00007-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olejnik J, Ryabchikova E, Corley RB, Mühlberger E. Intracellular events and cell fate in filovirus infection. Viruses. 2011;3:1501–1531. doi: 10.3390/v3081501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392:245–252. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van der Groen G, Pattyn SR. Measurement of antibodies to Ebola virus in human sera from N. W.-Zaire. Ann Soc Belg Med Trop. 1979;59:87–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saluzzo JF, Gonzalez J-P, Hervé JP, Georges AJ, Johnson KM. Preliminary note on the presence of antibodies to Ebola virus in the human population in the eastern part of the Central African Republic. Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales. 1980;73:238–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heymann DL, Weisfeld JS, Webb PA, Johnson KM, Cairns T, Berquist H. Ebola hemorrhagic fever: Tandala, Zaire, 1977–1978. J Infect Dis. 1980;142:372–376. doi: 10.1093/infdis/142.3.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bouree P, Bergmann JF. Ebola virus infection in man: a serological and epidemiological survey in the Cameroons. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1983;32:1465–1466. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1983.32.1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geisbert TW, Jaax NK. Marburg hemorrhagic fever: report of a case studied by immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy. Ultrastruct Pathol. 1998;22:3–17. doi: 10.3109/01913129809032253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wyers M, Formenty P, Cherel Y, Guigand L, Fernandez B, Boesch C, Le Guenno B. Histopathological and immunohistochemical studies of lesions associated with Ebola virus in a naturally infected chimpanzee. J Infect Dis. 1999;179(Suppl. 1):S54–S59. doi: 10.1086/514300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geisbert TW, Jahrling PB, Hanes MA, Zack PM. Association of Ebola-related Reston virus particles and antigen with tissue lesions of monkeys imported to the United States. J Comp Pathol. 1992;106:137–152. doi: 10.1016/0021-9975(92)90043-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Helft J, Manicassamy B, Guermonprez P, Hashimoto D, Silvin A, Agudo J, Brown BD, Schmolke M, Miller JC, Leboeuf M, et al. Cross-presenting CD103+ dendritic cells are protected from influenza virus infection. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:4037–4047. doi: 10.1172/JCI60659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steele K, Crise B, Kuehne A, Kell W. Ebola virus glycoprotein demonstrates differential cellular localization in infected cell types of nonhuman primates and guinea pigs. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:625–630. doi: 10.5858/2001-125-0625-EVGDDC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34•.Lüdtke A, Ruibal P, Wozniak DM, Pallasch E, Wurr S, Bockholt S, Gómez-Medina S, Qiu X, Kobinger GP, Rodríguez E, et al. Ebola virus infection kinetics in chimeric mice reveal a key role of T cells as barriers for virus dissemination. Sci Rep. 2017;7:43776. doi: 10.1038/srep43776. This is the first study demonstrating differential susceptibility of distinct dendritic cell subsets to Ebola virus infection in vivo. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Farrand KJ, Dickgreber N, Stoitzner P, Ronchese F, Petersen TR, Hermans IF. Langerin+ CD8alpha+ dendritic cells are critical for cross-priming and IL-12 production in response to systemic antigens. J Immunol. 2009;183:7732–7742. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bedoui S, Whitney PG, Waithman J, Eidsmo L, Wakim L, Caminschi I, Allan RS, Wojtasiak M, Shortman K, Carbone FR, et al. Cross-presentation of viral and self antigens by skin-derived CD103+ dendritic cells. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:488–495. doi: 10.1038/ni.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ribeiro CMS, Sarrami-Forooshani R, Setiawan LC, Zijlstra-Willems EM, van Hamme JL, Tigchelaar W, van der Wel NN, Kootstra NA, Gringhuis SI, Geijtenbeek TBH. Receptor usage dictates HIV-1 restriction by human TRIM5α in dendritic cell subsets. Nature. 2016;540:448–452. doi: 10.1038/nature20567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silvin A, Yu CI, Lahaye X, Imperatore F, Brault J-B, Cardinaud S, Becker C, Kwan W-H, Conrad C, Maurin M, et al. Constitutive resistance to viral infection in human CD141(+) dendritic cells. Sci Immunol. 2017;2:pii:eaai8071. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aai8071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ströher U, West E, Bugany H, Klenk HD, Schnittler HJ, Feldmann H. Infection and activation of monocytes by Marburg and Ebola viruses. J Virol. 2001;75:11025–11033. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.22.11025-11033.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wahl-Jensen V, Kurz S, Feldmann F, Buehler LK, Kindrachuk J, DeFilippis V, da Silva Correia J, Früh K, Kuhn JH, Burton DR, et al. Ebola virion attachment and entry into human macrophages profoundly effects early cellular gene expression. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1359. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41•.Olejnik J, Forero A, Deflubé LR, Hume AJ, Manhart WA, Nishida A, Marzi A, Katze MG, Ebihara H, Rasmussen AL, et al. Ebolaviruses associated with differential pathogenicity induce distinct host responses in human macrophages. J Virol. 2017;91:e00179–e217. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00179-17. This study provides a comprehensive characterization of inflammation induced by Ebola and Reston viruses in human macrophages. The authors demonstrate that Ebola but not Reston virus, induce TLR4-dependent inflammation in a glycoprotein-dependent manner. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gupta M, Mahanty S, Ahmed R, Rollin PE. Monocyte-derived human macrophages and peripheral blood mononuclear cells infected with ebola virus secrete MIP-1alpha and TNF-alpha and inhibit poly-IC-induced IFN-alpha in vitro. Virology. 2001;284:20–25. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.0836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hensley LE, Young HA, Jahrling PB, Geisbert TW. Proinflammatory response during Ebola virus infection of primate models: possible involvement of the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily. Immunol Lett. 2002;80:169–179. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(01)00327-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Okumura A, Pitha PM, Yoshimura A, Harty RN. Interaction between Ebola virus glycoprotein and host toll-like receptor 4 leads to induction of proinflammatory cytokines and SOCS1. J Virol. 2010;84:27–33. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01462-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Escudero-Pérez B, Volchkova VA, Dolnik O, Lawrence P, Volchkov VE. Shed GP of Ebola virus triggers immune activation and increased vascular permeability. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004509. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Okumura A, Rasmussen AL, Halfmann P, Feldmann F, Yoshimura A, Feldmann H, Kawaoka Y, Harty RN, Katze MG. Suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 is an inducible host factor that regulates virus egress during Ebola virus infection. J Virol. 2015;89:10399–10406. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01736-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van Montfoort N, van der Aa E, van den Bosch A, Brouwers H, Vanwolleghem T, Janssen HLA, Javanbakht H, Buschow SI, Woltman AM. Hepatitis B virus surface antigen activates myeloid dendritic cells via a soluble CD14-dependent mechanism. J Virol. 2016;90:6187–6199. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02903-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Modhiran N, Watterson D, Muller DA, Panetta AK, Sester DP, Liu L, Hume DA, Stacey KJ, Young PR. Dengue virus NS1 protein activates cells via Toll-like receptor 4 and disrupts endothelial cell monolayer integrity. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:304ra142. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa3863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Funchal GA, Jaeger N, Czepielewski RS, Machado MS, Muraro SP, Stein RT, Bonorino CBC, Porto BN. Respiratory syncytial virus fusion protein promotes TLR-4-dependent neutrophil extracellular trap formation by human neutrophils. PLOS ONE. 2015;10:e0124082. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50•.Stonier SW, Herbert AS, Kuehne AI, Sobarzo A, Habibulin P, Dahan CVA, James RM, Egesa M, Cose S, Lutwama JJ, et al. Marburg virus survivor immune responses are Th1 skewed with limited neutralizing antibody responses. J Exp Med. 2017;58 doi: 10.1084/jem.20170161. http://dx.doi.org/10.1084/jem.20170161. This study characterizes the immune memory of Marburg virus disease survivors long time after recovery. The authors demonstrate that Th1-type CD4 T cell responses dominate Marburg virus immune memory. Conversely, the study finds that long-term CD8 memory T cells do not seem to be maintained over time. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51••.McElroy AK, Akondy RS, Davis CW, Ellebedy AH, Mehta AK, Kraft CS, Lyon GM, Ribner BS, Varkey J, Sidney J, et al. Human Ebola virus infection results in substantial immune activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:4719–4724. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1502619112. This paper provides the first characterization of the kinetics and phenotype of T cells in human Ebola virus disease with modern multiparametric flow cytometry. The study demonstrates strong and sustained T cell activation beyond the acute phase of disease. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dabbagh K, Dahl ME, Stepick-Biek P, Lewis DB. Toll-like receptor 4 is required for optimal development of Th2 immune responses: role of dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2002;168:4524–4530. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iampietro M, Younan P, Nishida A, Dutta M, Lubaki NM, Santos RI, Koup RA, Katze MG, Bukreyev A. Ebola virus glycoprotein directly triggers T lymphocyte death despite of the lack of infection. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13:e1006397. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Feldmann H, Geisbert TW. Ebola haemorrhagic fever. Lancet. 2011;377:849–862. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60667-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Younan P, Iampietro M, Nishida A, Ramanathan P, Santos RI, Dutta M, Lubaki NM, Koup RA, Katze MG, Bukreyev A. Ebola virus binding to Tim-1 on T lymphocytes induces a cytokine storm. MBio. 2017;8:e00845–e917. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00845-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rialdi A, Campisi L, Zhao N, Lagda AC, Pietzsch C, Ho JSY, Martinez-Gil L, Fenouil R, Chen X, Edwards M, et al. Topoisomerase 1 inhibition suppresses inflammatory genes and protects from death by inflammation. Science. 2016;352:aad7993. doi: 10.1126/science.aad7993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Olejnik J, Forero A, Deflubé LR, Hume AJ, Manhart WA, Nishida A, Marzi A, Katze MG, Ebihara H, Rasmussen AL, et al. Ebolaviruses associated with differential pathogenicity induce distinct host responses in human macrophages. J Virol. 2017;91:e00179–17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00179-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Younan P, Ramanathan P, Graber J, Gusovsky F, Bukreyev A. The toll-like receptor 4 antagonist eritoran protects mice from lethal filovirus challenge. MBio. 2017;8:e00226–17. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00226-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Longhi MP, Trumpfheller C, Idoyaga J, Caskey M, Matos I, Kluger C, Salazar AM, Colonna M, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells require a systemic type I interferon response to mature and induce CD4+ Th1 immunity with poly IC as adjuvant. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1589–1602. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moltedo B, Li W, Yount JS, Moran TM. Unique type I interferon responses determine the functional fate of migratory lung dendritic cells during influenza virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002345. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pinto AK, Daffis S, Brien JD, Gainey MD, Yokoyama WM, Sheehan KCF, Murphy KM, Schreiber RD, Diamond MS. A temporal role of type I interferon signaling in CD8+ T cell maturation during acute West Nile virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002407. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62•.Rhein BA, Powers LS, Rogers K, Anantpadma M, Singh BK, Sakurai Y, Bair T, Miller-Hunt C, Sinn P, Davey RA, et al. Interferon-γ inhibits Ebola virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1005263. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005263. This study provides the first demonstration that not only type I but also type II interferons provide a barrier to Ebola virus infection. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dyall J, Hart BJ, Postnikova E, Cong Y, Zhou H, Gerhardt DM, Freeburger D, Michelotti J, Honko AN, Dewald LE, et al. Interferon-β and interferon-γ are weak inhibitors of Ebola virus in cell-based assays. J Infect Dis. 2017;215:1416–1420. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jahrling PB, Geisbert TW, Geisbert JB, Swearengen JR, Bray M, Jaax NK, Huggins JW, LeDuc JW, Peters CJ. Evaluation of immune globulin and recombinant interferon-alpha2b for treatment of experimental Ebola virus infections. J Infect Dis. 1999;179(Suppl. 1):S224–S234. doi: 10.1086/514310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Smith LM, Hensley LE, Geisbert TW, Johnson J, Stossel A, Honko A, Yen JY, Geisbert J, Paragas J, Fritz E, et al. Interferon-β therapy prolongs survival in rhesus macaque models of Ebola and Marburg hemorrhagic fever. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:310–328. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Qiu X, Wong G, Fernando L, Audet J, Bello A, Strong J, Alimonti JB, Kobinger GP. mAbs and Ad-vectored IFN-α therapy rescue Ebola-infected nonhuman primates when administered after the detection of viremia and symptoms. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:207ra143. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Olejnik J, Hume AJ, Leung DW, Amarasinghe GK, Basler CF, Mühlberger E. Filovirus strategies to escape antiviral responses. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2017;4:499–530. doi: 10.1007/82_2017_13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yen B, Mulder LC, Martinez O, Basler CF. Molecular basis for Ebola virus VP35 suppression of human dendritic cell maturation. J Virol. 2014;88:12500–12510. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02163-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69••.Ilinykh PA, Lubaki NM, Widen SG, Renn LA, Theisen TC, Rabin RL, Wood TG, Bukreyev A. Different temporal effects of Ebola virus VP35 and VP24 proteins on global gene expression in human dendritic cells. J Virol. 2015;89:7567–7583. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00924-15. This is a comprehensive study of the effects of the two main Ebola virus interferon antagonist proteins during infection of human dendritic cells. The authors use next-generation sequencing to characterize the pathways targeted by both proteins over the course of infection and compare the effects of wt Ebola viruses with those carrying mutations in the innate response-antagonizing domain (IRADs) of VP35 and VP24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lubaki NM, Younan P, Santos RI, Meyer M, Iampietro M, Koup RA, Bukreyev A. The Ebola interferon inhibiting domains attenuate and dysregulate cell-mediated immune responses. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1006031. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hartman AL, Dover JE, Towner JS, Nichol ST. Reverse genetic generation of recombinant Zaire Ebola viruses containing disrupted IRF-3 inhibitory domains results in attenuated virus growth in vitro and higher levels of IRF-3 activation without inhibiting viral transcription or replication. J Virol. 2006;80:6430–6440. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00044-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hartman AL, Ling L, Nichol ST, Hibberd ML. Whole-genome expression profiling reveals that inhibition of host innate immune response pathways by Ebola virus can be reversed by a single amino acid change in the VP35 protein. J Virol. 2008;82:5348–5358. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00215-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hartman AL, Bird BH, Towner JS, Antoniadou Z-A, Zaki SR, Nichol ST. Inhibition of IRF-3 activation by VP35 is critical for the high level of virulence of ebola virus. J Virol. 2008;82:2699–2704. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02344-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Volchkov VE, Chepurnov AA, Volchkova VA, Ternovoj VA, Klenk HD. Molecular characterization of guinea pig-adapted variants of Ebola virus. Virology. 2000;277:147–155. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ebihara H, Takada A, Kobasa D, Jones S, Neumann G, Theriault S, Bray M, Feldmann H, Kawaoka Y. Molecular determinants of Ebola virus virulence in mice. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e73. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mateo M, Carbonnelle C, Martinez MJ, Reynard O, Page A, Volchkova VA, Volchkov VE. Knockdown of Ebola virus VP24 impairs viral nucleocapsid assembly and prevents virus replication. J Infect Dis. 2011;204(Suppl. 3):S892–S896. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Reid SP, Valmas C, Martinez O, Sanchez FM, Basler CF. Ebola virus VP24 proteins inhibit the interaction of NPI-1 subfamily karyopherin alpha proteins with activated STAT1. J Virol. 2007;81:13469–13477. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01097-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78•.Deen GF, Broutet N, Xu W, Knust B, Sesay FR, McDonald SLR, Ervin E, Marrinan JE, Gaillard P, Habib N, et al. Ebola RNA persistence in semen of Ebola virus disease survivors — final report. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1428–1437. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1511410. This study determined the length of Ebola virus RNA persistence in semen of male survivors. The data demonstrate that viral RNA can be detected up to 18 months after discharge from the Ebola treatment unit. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Caballero IS, Honko AN, Gire SK, Winnicki SM, Melé M, Gerhardinger C, Lin AE, Rinn JL, Sabeti PC, Hensley LE, et al. In vivo Ebola virus infection leads to a strong innate response in circulating immune cells. BMC Genomics. 2016;17:707. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-3060-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Liu X, Speranza E, Munoz-Fontela C, Haldenby S, Rickett NY, García-Dorival I, Fang Y, Hall Y, Zekeng E-G, Lüdtke A, et al. Transcriptomic signatures differentiate survival from fatal outcomes in humans infected with Ebola virus. Genome Biol. 2017;18:4. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1137-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sanchez A, Lukwiya M, Bausch D, Mahanty S, Sanchez AJ, Wagoner KD, Rollin PE. Analysis of human peripheral blood samples from fatal and nonfatal cases of Ebola (Sudan) hemorrhagic fever: cellular responses, virus load, and nitric oxide levels. J Virol. 2004;78:10370–10377. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.19.10370-10377.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wauquier N, Becquart P, Padilla C, Baize S, Leroy EM. Human fatal Zaire Ebola virus infection is associated with an aberrant innate immunity and with massive lymphocyte apoptosis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010:4. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Towner JS, Rollin PE, Bausch DG, Sanchez A, Crary SM, Vincent M, Lee WF, Spiropoulou CF, Ksiazek TG, Lukwiya M, et al. Rapid diagnosis of Ebola hemorrhagic fever by reverse transcription-PCR in an outbreak setting and assessment of patient viral load as a predictor of outcome. J Virol. 2004;78:4330–4341. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.8.4330-4341.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bradfute SB, Warfield KL, Bavari S. Functional CD8+ T cell responses in lethal Ebola virus infection. J Immunol. 2008;180:4058–4066. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.4058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bradfute SB, Swanson PE, Smith MA, Watanabe E, McDunn JE, Hotchkiss RS, Bavari S. Mechanisms and consequences of ebolavirus-induced lymphocyte apoptosis. J Immunol. 2010;184:327–335. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gupta M, Mahanty S, Greer P, Towner JS, Shieh W-J, Zaki SR, Ahmed R, Rollin PE. Persistent infection with ebola virus under conditions of partial immunity. J Virol. 2004;78:958–967. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.2.958-967.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87••.Ruibal P, Oestereich L, Lüdtke A, Becker-Ziaja B, Wozniak DM, Kerber R, Korva M, Cabeza-Cabrerizo M, Bore JA, Koundouno FR, et al. Unique human immune signature of Ebola virus disease in Guinea. Nature. 2016;533:100–104. doi: 10.1038/nature17949. This study compares T cell responses in survivor and fatal Ebola virus disease patients in Guinea during the West African outbreak. It shows that differences in the T cell response are restricted to immune checkpoints (CTLA-4 and PD-1) which are highly upregulated in fatalities. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.McElroy AK, Akondy RS, Davis CW, Ellebedy AH, Mehta AK, Kraft CS, Lyon GM, Ribner BS, Varkey J, Sidney J, et al. Human Ebola virus infection results in substantial immune activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:4719–4724. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1502619112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rowe AK, Bertolli J, Khan AS, Mukunu R, Muyembe-Tamfum JJ, Bressler D, Williams AJ, Peters CJ, Rodriguez L, Feldmann H, et al. Clinical, virologic, and immunologic follow-up of convalescent Ebola hemorrhagic fever patients and their household contacts, Kikwit, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Commission de Lutte contre les Epidémies à Kikwit. J Infect Dis. 1999;179(Suppl. 1):S28–S35. doi: 10.1086/514318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Luczkowiak J, Arribas JR, Gómez S, Jiménez-Yuste V, la Calle de F, Viejo A, Delgado R. Specific neutralizing response in plasma from convalescent patients of Ebola Virus Disease against the West Africa Makona variant of Ebola virus. Virus Res. 2016;213:224–229. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2015.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zeitlin L, Whaley KJ, Olinger GG, Jacobs M, Gopal R, Qiu X, Kobinger GP. Antibody therapeutics for Ebola virus disease. Curr Opin Virol. 2016;17:45–49. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sobarzo A, Ochayon DE, Lutwama JJ, Balinandi S, Guttman O, Marks RS, Kuehne AI, Dye JM, Yavelsky V, Lewis EC, et al. Persistent immune responses after ebola virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:492–493. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1300266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sobarzo A, Groseth A, Dolnik O, Becker S, Lutwama JJ, Perelman E, Yavelsky V, Muhammad M, Kuehne AI, Marks RS, et al. Profile and persistence of the virus-specific neutralizing humoral immune response in human survivors of Sudan ebolavirus (Gulu) J Infect Dis. 2013;208:299–309. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sobarzo A, Stonier SW, Herbert AS, Ochayon DE, Kuehne AI, Eskira Y, Fedida-Metula S, Tali N, Lewis EC, Egesa M, et al. Correspondence of neutralizing humoral immunity and CD4 T cell responses in long recovered sudan virus survivors. Viruses. 2016;8:133. doi: 10.3390/v8050133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Clark DV, Kibuuka H, Millard M, Wakabi S, Lukwago L, Taylor A, Eller MA, Eller LA, Michael NL, Honko AN, et al. Long-term sequelae after Ebola virus disease in Bundibugyo, Uganda: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:905–912. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)70152-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Etard J-F, Sow MS, Leroy S, Touré A, Taverne B, Keita AK, Msellati P, Magassouba N, Baize S, Raoul H, et al. Multidisciplinary assessment of post-Ebola sequelae in Guinea (Postebogui): an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:545–552. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30516-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mattia JG, Vandy MJ, Chang JC, Platt DE, Dierberg K, Bausch DG, Brooks T, Conteh S, Crozier I, Fowler RA, et al. Early clinical sequelae of Ebola virus disease in Sierra Leone: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:331–338. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00489-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chancellor JR, Padmanabhan SP, Greenough TC, Sacra R, Ellison RT, Madoff LC, Droms RJ, Hinkle DM, Asdourian GK, Finberg RW, et al. Uveitis and systemic inflammatory markers in convalescent phase of Ebola virus disease. Emerging Infect Dis. 2016;22:295–297. doi: 10.3201/eid2202.151416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99••.Jacobs M, Rodger A, Bell DJ, Bhagani S, Cropley I, Filipe A, Gifford RJ, Hopkins S, Hughes J, Jabeen F, et al. Late Ebola virus relapse causing meningoencephalitis: a case report. Lancet. 2016;388:498–503. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30386-5. Case-report describing reactivation of Ebola virus infection in the central nervous system long after recovery from acute disease. First report demonstrating that Ebola virus may persist in the CNS and cause late-onset encephalitis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100••.Varkey JB, Shantha JG, Crozier I, Kraft CS, Lyon GM, Mehta AK, Kumar G, Smith JR, Kainulainen MH, Whitmer S, et al. Persistence of Ebola virus in ocular fluid during convalescence. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2469. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500306. This case-report provides the first evidence that infectious Ebola virus may persist in ocular fluid and cause late-onset uveitis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hong S, Van Kaer L. Immune privilege: keeping an eye on natural killer T cells. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1197–1200. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.9.1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102•.Zeng X, Blancett CD, Koistinen KA, Schellhase CW, Bearss JJ, Radoshitzky SR, Honnold SP, Chance TB, Warren TK, Froude JW, et al. Identification and pathological characterization of persistent asymptomatic Ebola virus infection in rhesus monkeys. Nat Microbiol. 2017;2:17113. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.113. This paper describes for the first time Ebola virus persistence in an experimental animal model (non-human primates). The study opens a window of opportunity to study the physiological mechanisms of Ebola virus persistence, and demonstrate accumulation of CD68+ macrophages at the sites of virus persistence. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Schmaljohn A, Lewis GK. Cell-targeting antibodies in immunity to Ebola. Pathog Dis. 2016;74:ftw021. doi: 10.1093/femspd/ftw021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Reynolds P, Marzi A. Ebola and Marburg virus vaccines. Virus Genes. 2017;53:501–515. doi: 10.1007/s11262-017-1455-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sullivan NJ, Hensley L, Asiedu C, Geisbert TW, Stanley D, Johnson J, Honko A, Olinger G, Bailey M, Geisbert JB, et al. CD8+ cellular immunity mediates rAd5 vaccine protection against Ebola virus infection of nonhuman primates. Nat Med. 2011;17:1128–1131. doi: 10.1038/nm.2447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Marzi A, Engelmann F, Feldmann F, Haberthur K, Shupert WL, Brining D, Scott DP, Geisbert TW, Kawaoka Y, Katze MG, et al. Antibodies are necessary for rVSV/ZEBOV-GP-mediated protection against lethal Ebola virus challenge in nonhuman primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:1893–1898. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209591110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ledgerwood JE, Costner P, Desai N, Holman L, Enama ME, Yamshchikov G, Mulangu S, Hu Z, Andrews CA, Sheets RA, et al. A replication defective recombinant Ad5 vaccine expressing Ebola virus GP is safe and immunogenic in healthy adults. Vaccine. 2010;29:304–313. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ledgerwood JE, DeZure AD, Stanley DA, Novik L, Enama ME, Berkowitz NM, Hu Z, Joshi G, Ploquin A, Sitar S, et al. Chimpanzee adenovirus vector Ebola vaccine — preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2014;373:776. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1505499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Zhu F-C, Wurie AH, Hou L-H, Liang Q, Li Y-H, Russell JBW, Wu S-P, Li J-X, Hu Y-M, Guo Q, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a recombinant adenovirus type-5 vector-based Ebola vaccine in healthy adults in Sierra Leone: a single-centre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:621–628. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32617-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Huttner A, Combescure C, Grillet S, Haks MC, Quinten E, Modoux C, Agnandji ST, Brosnahan J, Dayer J-A, Harandi AM, et al. A dose-dependent plasma signature of the safety and immunogenicity of the rVSV-Ebola vaccine in Europe and Africa. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9:eaaj1701. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaj1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Tapia MD, Sow SO, Lyke KE, Haidara FC, Diallo F, Doumbia M, Traore A, Coulibaly F, Kodio M, Onwuchekwa U, et al. Use of ChAd3-EBO-Z Ebola virus vaccine in Malian and US adults, and boosting of Malian adults with MVA-BN-Filo: a phase 1, single-blind, randomised trial, a phase 1b, open-label and double-blind, dose-escalation trial, and a nested, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;16:31–42. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00362-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.De Santis O, Audran R, Pothin E, Warpelin-Decrausaz L, Vallotton L, Wuerzner G, Cochet C, Estoppey D, Steiner-Monard V, Lonchampt S, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a chimpanzee adenovirus-vectored Ebola vaccine in healthy adults: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-finding, phase 1/2a study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:311–320. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00486-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Agnandji ST, Huttner A, Zinser ME, Njuguna P, Dahlke C, Fernandes JF, Yerly S, Dayer J-A, Kraehling V, Kasonta R, et al. Phase 1 trials of rVSV Ebola vaccine in Africa and Europe —preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2015;374:1647–1660. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1502924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ewer K, Rampling T, Venkatraman N, Bowyer G, Wright D, Lambe T, Imoukhuede EB, Payne R, Fehling SK, Strecker T, et al. A monovalent chimpanzee adenovirus Ebola vaccine boosted with MVA. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1635–1646. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Dolzhikova IV, Zubkova OV, Tukhvatulin AI, Dzharullaeva AS, Tukhvatulina NM, Shcheblyakov DV, Shmarov MM, Tokarskaya EA, Simakova YV, Egorova DA, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of GamEvac-Combi, a heterologous VSV- and Ad5-vectored Ebola vaccine: an open phase I/II trial in healthy adults in Russia. Hum Vaccines Immunotherap. 2017;13:613–620. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2016.1238535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.ElSherif MS, Brown C, MacKinnon-Cameron D, Li L, Racine T, Alimonti J, Rudge TL, Sabourin C, Silvera P, Hooper JW, et al. Assessing the safety and immunogenicity of recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus Ebola vaccine in healthy adults: a randomized clinical trial. CMAJ. 2017;189:E819–E827. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.170074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Heppner DG, Kemp TL, Martin BK, Ramsey WJ, Nichols R, Dasen EJ, Link CJ, Das R, Xu ZJ, Sheldon EA, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of the rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP Ebola virus vaccine candidate in healthy adults: a phase 1b randomised, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-response study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:854–866. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30313-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kennedy SB, Bolay F, Kieh M, Grandits G, Badio M, Ballou R, Eckes R, Feinberg M, Follmann D, Grund B, et al. Phase 2 placebo-controlled trial of two vaccines to prevent Ebola in Liberia. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1438–1447. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1614067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Henao-Restrepo AM, Longini IM, Egger M, Dean NE. Efficacy and effectiveness of an rVSV-vectored vaccine expressing Ebola surface glycoprotein: interim results from the Guinea ring vaccination cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2015;386:857–866. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]