Abstract

α-Dystroglycanopathies are a group of muscular dystrophies characterized by α-DG hypoglycosylation and reduced extracellular ligand-binding affinity. Among other genes involved in the α-DG glycosylation process, fukutin related protein (FKRP) gene mutations generate a wide range of pathologies from mild limb girdle muscular dystrophy 2I (LGMD2I), severe congenital muscular dystrophy 1C (MDC1C), to Walker-Warburg Syndrome and Muscle-Eye-Brain disease. FKRP gene encodes for a glycosyltransferase that in vivo transfers a ribitol phosphate group from a CDP –ribitol present in muscles to α-DG, while in vitro it can be secreted as monomer of 60kDa. Consistently, new evidences reported glycosyltransferases in the blood, freely circulating or wrapped within vesicles. Although the physiological function of blood stream glycosyltransferases remains unclear, they are likely released from blood borne or distant cells. Thus, we hypothesized that freely or wrapped FKRP might circulate as an extracellular glycosyltransferase, able to exert a “glycan remodelling” process, even at distal compartments. Interestingly, we firstly demonstrated a successful transduction of MDC1C blood-derived CD133+ cells and FKRP L276IKI mouse derived satellite cells by a lentiviral vector expressing the wild-type of human FKRP gene. Moreover, we showed that LV-FKRP cells were driven to release exosomes carrying FKRP. Similarly, we observed the presence of FKRP positive exosomes in the plasma of FKRP L276IKI mice intramuscularly injected with engineered satellite cells. The distribution of FKRP protein boosted by exosomes determined its restoration within muscle tissues, an overall recovery of α-DG glycosylation and improved muscle strength, suggesting a systemic supply of FKRP protein acting as glycosyltransferase.

Introduction

The congenital muscular dystrophies (CMDs) are a group of clinically heterogeneous infantile autosomal disorders, typically characterized by dystrophic symptoms such as skeletal muscle weakness and contractures, marked psychomotor developmental delays, and cardiac and neurological defects. In addition to the well-known CMDs dependent on dystrophin mutations (1), α-Dystroglycanopathy is a newly emerging subgroup determined by gene mutations associated to a defective α-Dystroglycan (α-DG) glycosylation. The glycoprotein α-DG is placed on the peripheral membrane of muscle tissues, and it is characterized by a peculiar O-mannose –linked glycan structure that exerts a key role in binding the internal actin cytoskeleton of muscle fibers to the protein ligands of the extracellular matrix basal lamina (i.e. laminin, agrin, and perlecan). Therefore, defects in α-DG glycosylation lead to impaired cell membrane integrity, loss of structural stability, fiber damage and continuous regeneration/degeneration cycles. The proper α-DG- extracellular matrix (ECM) ligand binding function is strictly regulated by the unique structure and the complex glycosylation of all the sugar moieties composing the α-DG (2), thus suggesting the existence of several autosomal recessive mutations in genes directly involved into glycosylation modifications. Among the most known mutated genes, Protein-O-mannosyl transferase 1 (POMT1) and Protein-O-mannosyl transferase 2 (POMT2), catalyse the initial O-mannosylation of α-DG (3); LARGE acts as a bifunctional glycosyltransferase of xylose and glucuronic acid (4). Fukutin-related protein (FKRP) is implicated in post-phosphoryl modification of α-DG (5) and underlies both the severe congenital muscular dystrophy type 1 (MDC1C) and the mild limb girdle muscular dystrophy type 2I (LGMD2I), two forms of dystrophy associated with a wide spectrum of clinical severity (6). In particular, it has been recently published that FKRP acts in tandem with Fukutin as transferase of ribitol 5-phosphate (Rbo5P), transferring a ribitol phosphate group from CDP-ribitol, a rare sugar unit presented in muscle to α-DG (7). Although CDP-ribitol clearly represents a donor substrate for FKRP, the precise sequence of action leading to CDP-ribitol transportation to the Golgi, as well as the exact site where ribitol phosphate groups are incorporated into O-mannose glycan structure, is still poorly described (8). Moreover, the relegation of glycosyltransferases within the ER-Golgi apparatus belongs to a glycosylation concept that has been recently out-dated, thanks to the identification of blood derived circulating glycosyltransferases that can affect glycans on distant cells and extracellular environment (9). In this new scenario, we hypothesized that FKRP might circulate as an extracellular glycosyltransferase, able to modify distal glycan structures. Interestingly, we employed a lentiviral vector expressing the wild-type of human FKRP gene to demonstrate the feasibility of transducing both dystrophic blood derived CD133+ cells, isolated from a MDC1C patient with FKRP gene alterations, and satellite cells derived from FKRP L276IKI mouse model (10). Moreover, we showed that FKRP transduced cells were driven to release exosomes carrying FKRP. Similarly, we observed the presence of blood freely circulating FKRP carried by exosomes isolated from plasma of FKRP L276IKI mice intramuscularly injected with ex vivo-engineered satellite cells. Furthermore, we performed exosome tracking in vitro exploiting a microfluidic bioreactor to reproduce in vivo kinetics, timing of distribution and fusion to targeted tissues. The dual distribution of FKRP protein determined its expression restoration within muscle tissues, an overall recovery of α-DG glycosylation, and improved muscle strength, suggesting a systemic supply of FKRP protein acting as glycosyltransferase.

Results

FKRP expression in transduced human MDC1C CD133+ blood-derived stem cells and murine FKRP L276IKI satellite cells

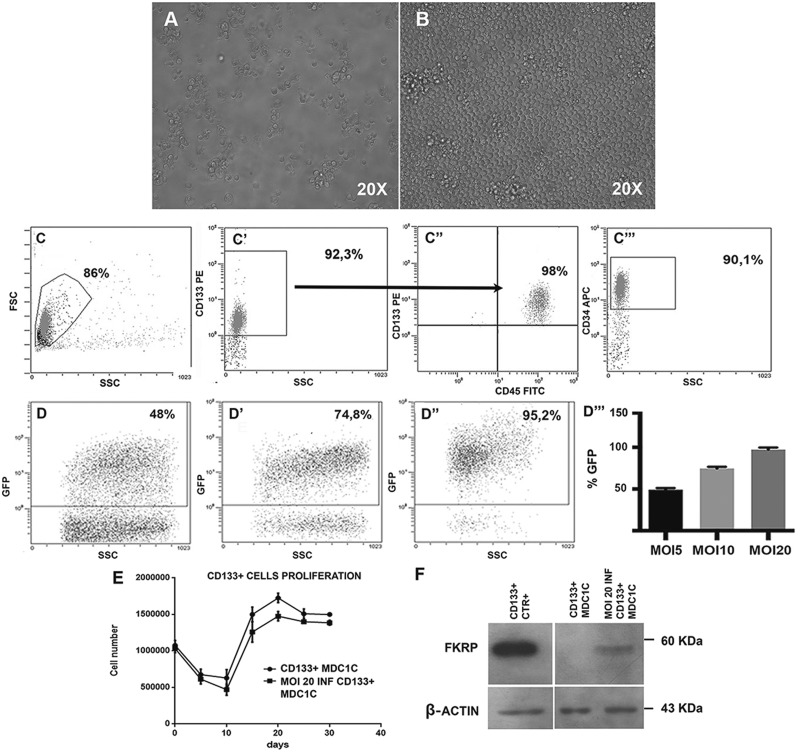

Human MDC1C CD133+ blood-derived stem cells. Following cells isolation through magnetic columns, CD133+ cells were immediately cultured in vitro; culture maintenance did not affect morphology of cells that remained round in shape and uniform in size immediately after the isolation (Fig. 1A), as well as after 2 weeks in culture (Fig. 1B). 98% of magnetically isolated CD133+ stem cells from MDC1C peripheral blood (Fig. 1C, gate) (median purity 92.3% ± 1,8 SD) (Fig. 1C’) showed CD45 co-expression (Fig. 1C’’), and the expression of CD34 marker (90.1% positivity) (Fig. 1C’’’). Immediately after cell isolation, cells were transduced with a lentiviral vector carrying the wild type form of FKRP gene (pLenti-CAG (hFKRP)-Rsv (GFP-Puro)), with three different MOI: 5, 10 and 20. FACS analyses of GFP expression performed on CD133+ blood-derived stem cells infected with LV-FKRP revealed a transduction efficiency proportional to the MOI increase: 48%, 74.8%, and up to 95.2%, respectively, for MOI of 5, 10 and 20 (Fig. 1D, D’ and D’’). These data were summarized in the histogram graph in Figure 1D’’’. Since MOI of 20 presented the best outcomes in terms of transduction efficacy (Fig. 1D’’ and D’’’), we proceeded to infect MDC1C blood-derived CD133+ stem cells with lentiviral MOI 20. Trypan blue exclusion assay performed on LV-FKRP CD133+ stem cells infected with this MOI did not display detrimental effects on cell proliferation, for all the experimental time points. MOI 20 transduced FKRP CD133+ stem cell proliferation curve resembled the characteristic curve of not infected CD133+ blood-derived stem cells, with an initial decrease of cell viability and a peak between 15 and 20 days (Fig. 1E). WB analysis performed 7 days after infection confirmed the restoration of lentivirus mediated wild type fukutin related protein expression in the engineered human MDC1C blood-derived CD133+ stem cells (Fig. 1F, lane MOI 20 INF CD133+ MDC1C). Consistently with the specificity of FKRP-STEM antibody for the wild type isoform of FKRP, not infected dystrophic CD133+ blood-derived stem cells (Fig. 1F, lane CD133+ MDC1C) expressing mutated protein did not show any positive corresponding band at 60kDa, while expression of FKRP in human healthy CD133+ blood derived stem cells was clearly detectable (Fig. 1F, lane CD133 CTR+).

Figure 1.

Characterization of CD133+ blood-derived stem cells isolated from a MDC1C patient. Cells morphology was evaluated by bright field microscopy (Leica LMD6000B) immediately after cells isolation (A) and after 14 days in proliferation medium (B). Images were captured at 20X magnification. FACS immunophenotyping of isolated blood-derived CD133+ stem cells. Each study included at least 15,000–30,000 events. The scatter plot is reported (C). The median purity of positively selected CD133+ stem cells after magnetic cell sorting was about 92,3% (C’); 98% of CD133+ cells co-expressed CD45 (C’’) and 90,1% of the isolated cell population was also CD34+ (C’’’). FACS immunophenotyping of CD133+ blood-derived stem cells infected with the lentiviral vector (pLenti-CAG (hFKRP)-Rsv (GFP-Puro)). The percentage of GFP+ cells was 48% (MOI 5) (D), 74.8% (MOI 10) (D’) and 95.2% (MOI 20) (D’’), respectively. Representative histogram of CD133+ stem cells transduction efficiency at MOI 5, 10 and 20 (D’’’). Values are expressed as means ± SD. MOI 20 infected and not infected MDC1C CD133+ blood-derived stem cells proliferation curve. Proliferation was evaluated in triplicate at different time-points (5-days intervals for 30 days) by counting cells with Trypan Blue Exclusion Assay (E). Values are expressed as means ± SD. Immunoblotting analysis confirmed FKRP protein expression (60 KDa) in MDC1C CD133+ blood-derived stem cells infected with the LV-hFKRP lentiviral vector at MOI 20 (MOI 20 INF CD133+ MDC1C, lane 3). Not infected MDC1C CD133+ cells (CD133+ MDC1C, lane 2) and healthy CD133+ (CD133+ CTR+, lane 1) were respectively loaded as positive and negative controls. β-actin was used as house-keeping protein (43 KDa) (F).

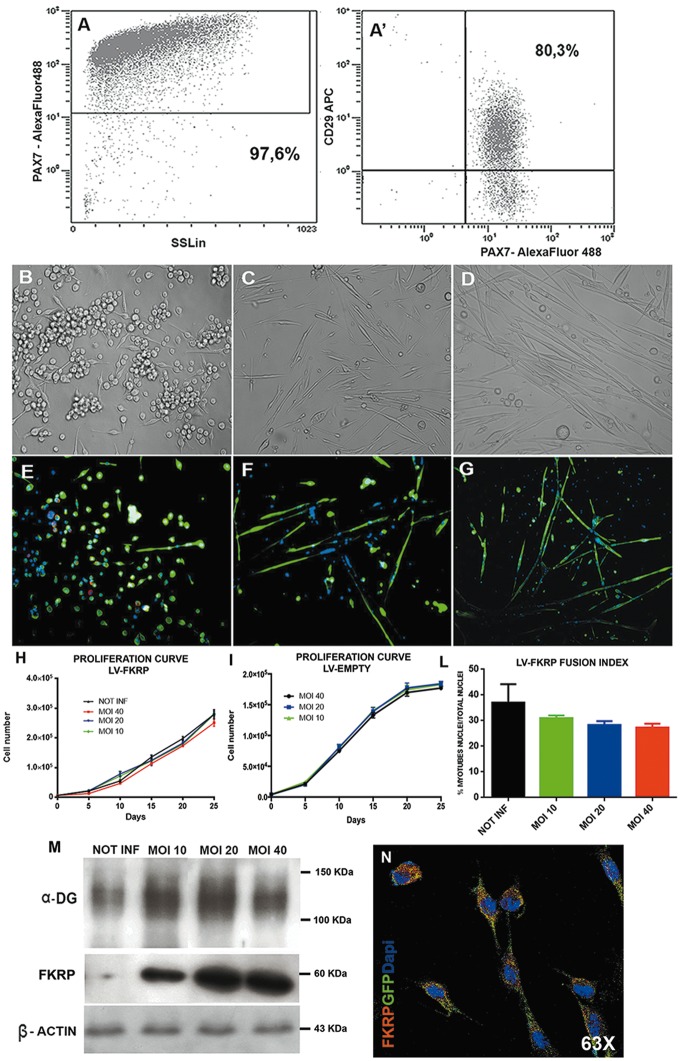

FKRP L276IKI satellite cells. Satellite cells population was isolated from FKRP L276IKI new born mice and plated in 48-wells tissue culture plates in expansion medium. FACS analysis demonstrated that 97.6% of isolated cells were Pax7+ (Fig. 2A) and 80.3% of Pax7+ cells co-expressed CD29 marker (Fig. 2A’). SCs morphology and expression of specific myogenic markers were evaluated at different time-points after culturing cells in myogenic differentiation medium (Fig. 2E–G;Supplementary Material, Fig. S1). Before the supplementation of serum starvation medium (T0), SCs showed the maintenance of Pax7 (in red in Fig. 2E) and desmin (in green in Fig. 2E) expression, while at T7 they started to elongate and form small Pax7-desmin+ myotubes (Fig. 2F) that increased in number and size after 14 days (T14) (Fig. 2G). We determined which pLenti-CAG (hFKRP)-Rsv (GFP-Puro) MOI was most effective in transducing FKRP L276IKI SCs in terms of SC viability and transduction efficiency. FKRP L276IKI SCs infected with lentiviral MOI of 10 and 20 did not show negative effects on viability compared to the not infected cells for all the time points, as confirmed by Trypan Blue Exclusion assay (Fig. 2H). Likewise, transduction with higher MOI (MOI 40) generated a tendency towards a slower proliferation rate of FKRP L276IKI SCs (determined by about 5% of cell mortality) (Fig. 2H). Interestingly, proliferation rate of FKRP L276IKI SCs infected with LV empty (pLenti-Rsv (GFP-Puro)) did not display any statistical differences between MOI 10, 20 and 40 (Fig. 2I). For MOI 40 it is only noticeable that cell proliferation seemed to face a not significant tendency towards a proliferation rate slow down starting from day 15 that might be caused by the occurrence of 3.5% cell mortality. Thus, we can exclude the occurrence of FKRP L276IKI SCs toxicity induced by lentivirus vectors, either the one carrying wild type FKRP isoform or the empty GFP cassette, even for long time of culture (25 days). SCs fusion index expressed as % of myotubes nuclei/number of total nuclei was found to be comparable between cells infected with MOI 10, 20 and 40 (Fig. 2L). We evaluated also the fusion index of FKRP L276IKI SCs infected with LV empty (pLenti-Rsv (GFP-Puro))(data not shown), but no differences were evidenced between MOI 10, 20 and 40, which maintained values comparable to not-infected FKRP L276IKI SCs (30% myotubes nuclei/total nuclei) (Fig. 2L). A not statistically different fusion index was evaluated for MOI 40 infected FKRP L276IKI SCs that might be reasonably caused by an overall slightly decreased cell number rather than by a decreased differentiation capacity. GFP expression performed on transduced FKRP L276IKI SCs infected with LV-FKRP revealed a transduction efficiency after 72 h proportional to the MOI increase: 41.3, 89.2 and 89.8%, respectively, for MOI of 10, 20 and 40. The GFP expression grew up to 99.2% after puromycin selection in all MOI tested. FKRP evaluation by WB analysis highlighted an increasing trend of protein expression between MOI of 10 and 20, while the MOI of 40 seemed to represent a steady point leading to FKRP expression plateau (Fig. 2M). Of note the achievement of FKRP expression plateau at MOI 40 is still associated with a constant level of α-DG glycosylation that seemed not to present MOI-dependent changes (Fig. 2M). IF staining of MOI 20 LV- FKRP L276IKI SCs by anti- GFP and anti FKRP-STEM antibodies confirmed the diffusion of GFP (in green in Fig. 2N;Supplementary Material, Fig. S1D’) within the cell cytoplasm, while exogenous FKRP (in red in Fig. 2N;Supplementary Material, Fig. S1D’’) was also found cytoplasmic but more localized nearby the cell nucleus. According to these results, for the in vivo experiments we infected FKRP L276IKI SCs with the optimal MOI 20 giving the higher transduction efficiency and the lower cell mortality.

Figure 2.

Characterization of FKRP L276IKI satellite cells. FACS immunophenotyping of freshly isolated FKRP L276IKI satellite cells. Each study included at least 15,000–30,000 events. 97,6% cells were PAX7+ (A), 80,3% of PAX7+ cells co-expressed CD29 marker (A’). Cells morphology was evaluated by bright field microscopy at different time-points: immediately after cells seeding (T0) (B), after 7 days (T7) (C) and 14 days (T14) (D) in myogenic differentiation medium (serum starvation condition). Immunofluorescent analysis was performed to evaluate specific myogenic satellite markers expression. At T0, satellite clones were positive for α-desmin (in green) and Pax7 (in red) (E). At T7 cells lost the expression of the early myogenic marker Pax7, and maintained the expression of α-desmin; α -desmin staining highlighted the presence of a few myotubes (F). At T14, cells were still positive for α-desmin and were finally fused to form myotubes (G). Images were captured at 20X magnification. LV-FKRP infected and not infected satellite cells proliferation curve (H) and LV-EMPTY infected and not infected satellite cells proliferation curve (I). SCs proliferation was evaluated every 5 days for 25 days by counting cells with Trypan Blue Exclusion Assay. Values are expressed as means ± SD. Evaluation of LV-FKRP infected (MOI 10, 20 and 40) and not infected (NOT INF) satellite cells fusion index, representing the % of myotubes nuclei/number of total nuclei, after 7 days in serum starvation (J). Values are expressed as means ± SD. Immunoblotting analysis confirmed α-DG protein glycosylation (smeared band 150 KDa) and FKRP protein expression (60 KDa) in infected satellite cells. α-DG signal was slightly increased between not-injected cells (NOT-INF, lane 1) and LV-FKRP injected cells, but showed no differences between MOI 10, 20 and 40 (MOI 10, lane 2, MOI 20, lane 3, MOI 40, lane 4). FKRP positive signal increased between MOI 10 and 20 but reached a plateau with MOI 40, not infected FKRP L276IKI satellite cell lysate was used as negative control. β-actin (43 KDa) was used as house-keeping protein (K). Immunofluorescent analysis of MOI 20 infected satellite cells, showing both cytoplasmic and perinuclear FKRP (in red) and cytoplasmic GFP (in green) expression. Nuclei were stained with Dapi (in blu). Images were taken with a confocal microscope (Leica SP2) at 63X magnification (L).

In vitro release of wild type FKRP carrying- exosome

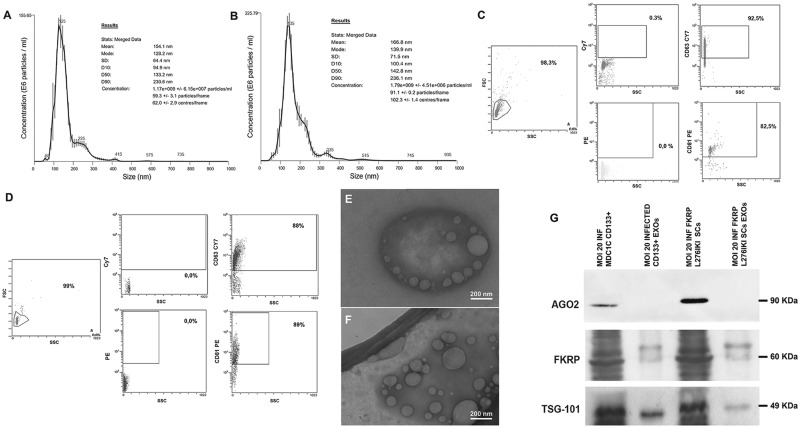

In line with previous results showing in vitro secretion on FKRP (11), we have hypothesized that FKRP protein could be transported by exosomes released in vitro from transduced cells. For this purpose, we have isolated exosomes from MOI 20 transduced MDC1C CD133+ blood-derived stem cell and MOI 20 transduced FKRP L276IKI SCs supernatants by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) procedure. NTA analysis confirmed the presence of exosomes in both cell populations. MDC1C CD133+ blood-derived stem cells released exosomes (NTA concentration 1.17×109 particles/ml) with a mean size of 154.1 nm and a mode size of 128.2 nm (Fig. 3A), while FKRP L276KI SCs-derived exosomes (NTA concentration 1.79×109 particles/ml), showed a mean size of 166.8 nm and a mode size of 139.9 nm (Fig. 3B). FACS analysis confirmed the expression of CD63 and CD81 tetraspanins both in MDC1C CD133+ derived exosomes (92.2% positivity for CD63 marker, 82.5% positivity for CD81 marker) (Fig. 3C) and in FKRP L276IKI SCs-secreted particles (88% positivity for CD63 marker, 89% positivity for CD81 marker) (Fig. 3D). Both exosome preparations exhibited a cup-shaped morphology in transmission electron microscopic images (Fig. 3E and F;Supplementary Material, Fig. S2A and B). Overall, exosome dimensions and morphology were found to be comparable between the two observed populations (92.7 nm ± 39.5 nm SD for MDC1C CD133+ blood-derived stem cells exosomes, and 109 nm ± 46.3 nm SD for FKRP L276IKI SCs secreted exosomes). WB was performed using anti FKRP-STEM antibody on transduced cell lysates (Fig. 3G, MOI 20 INF CD133+ MDC1C cells, lane 1; MOI 20 INF L276IKI FKRP SCs, lane 3) and the related exosomes (Fig. 3G, MOI 20 INF CD133+ MDC1C EXOs, MOI 20 INF L276IKI FKRP SCs, lanes 2, 4). The biochemical analysis showed exogenous FKRP corresponding band at 60 kDa, in the infected CD133+ cell and SCs lysates and in the corresponding secreted exosome lanes. The absence of Ago2 protein staining (90KDa) let exclude any kind of contamination during exosome samples preparation (12); TSG-101 detection proved the specificity of exosomal FKRP expression (Fig. 3G) (13).

Figure 3.

Exosomes characterization. Nanosight Tracking Analysis (NTA) of exosomes derived from MOI 20 infected MDC1C CD133+ blood-derived cells (A) and FKRP L276IKI satellite cells (B). Plots represent the average value of three recordings performed for each sample. Size and particle distribution (concentration) are reported. FACS immunophenotyping of MOI 20 transduced MDC1C CD133+ stem cells- (C) and MOI 20 transduced FKRP L276IKI satellite cells- released exosomes (D). Each study included at least 100,000 events. 92,2% of CD133+-derived exosomes were CD63+ and 82,5% were CD81+; 88% of SCs-derived exosomes were CD63+ and 89% CD81+. Magnified view of Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) micrograph of exosomes released from transduced MOI 20 MDC1C CD133+ blood-derived stem cells (mean value 92,7 nm ± 39,5 nm SD) (E) and FKRP L276IKI satellite cells (mean value 109 nm ± 46,3 nm SD) (F). Exosome diameters were measured using NIH ImageJ software. Scale bar, 200 nm. Western blot analysis of exosomal TSG-101, AGO2 and FKRP proteins extracted from MOI 20 transduced MDC1C CD133+ stem cells- (MOI 20 INF MDC1C CD133+ EXOs, lane 2) and MOI 20 FKRP L276IKI satellite cells- (MOI 20 INF L276IKI FKRP EXOs, lane 4) derived exosomes. MOI 20 infected CD133+ blood-derived cell lysate (MOI 20 INF MDC1C CD133+, lane 1) and MOI 20 infected satellite cells lysate (MOI 20 INF L276IKI FKRP, lane 3) were loaded as positive controls.

In vivo transplantation of LV-FKRP L276IKI satellite cells into FKRP L276IKI mouse models

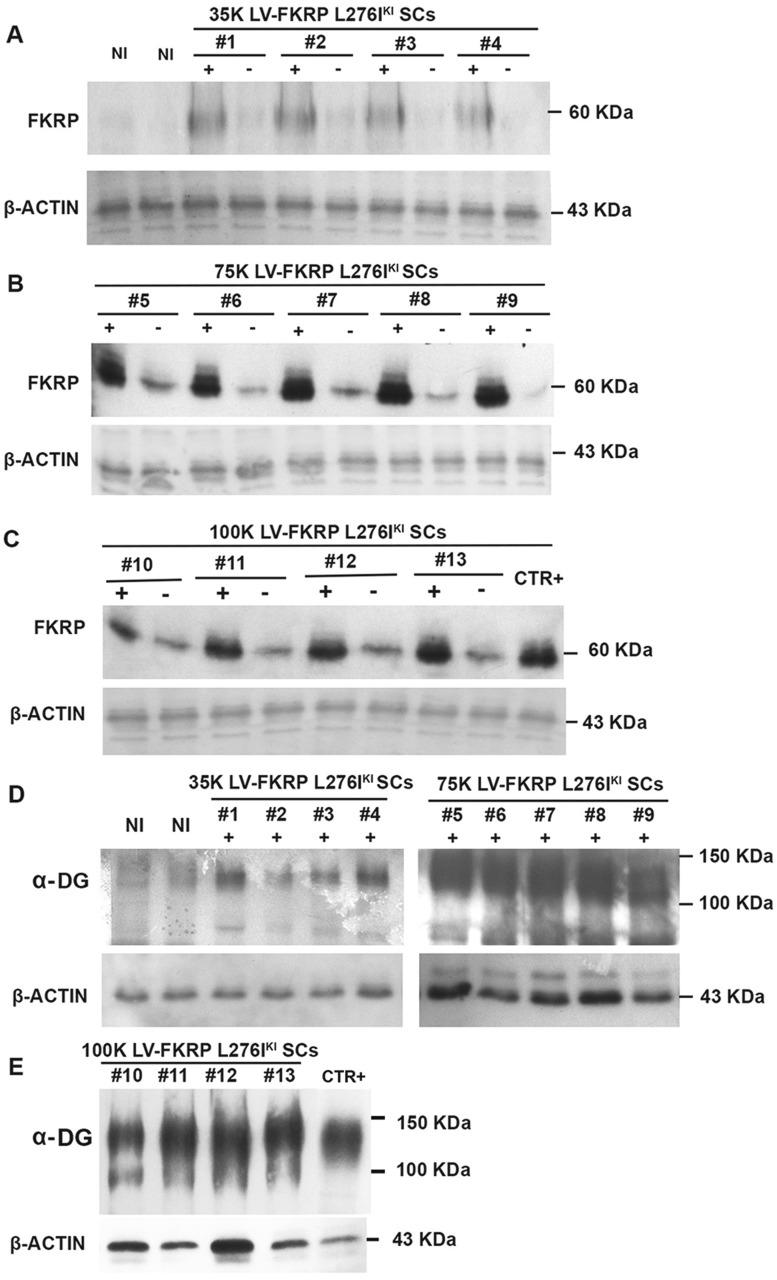

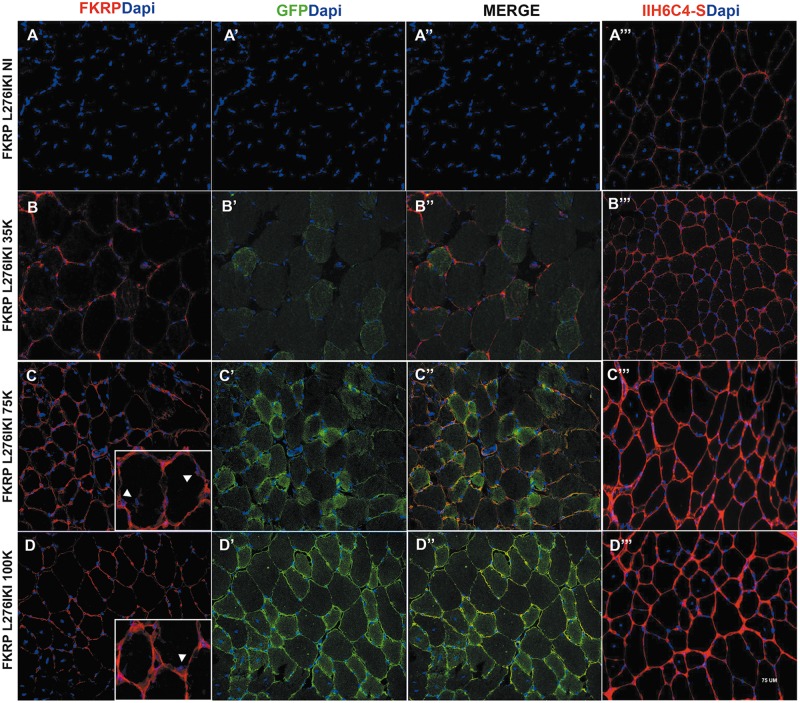

Satellite cells isolated from FKRP L276IKI new born mice and engineered with the lentiviral vector expressing the full length wild-type isoform of FKRP gene were intramuscularly transplanted into the right tibialis anterior of 12 months-old FKRP L276IKI mice. We aimed at demonstrating that 1) infected LV-FKRP L276IKI SCs could fuse with the host muscle tissue surrounding the transplantation site, thus ameliorating the dystrophic phenotype, while 2) the release of exosomes carrying wild type FKRP was able to induce an overall expression of FKRP and α-DG glycosylation, even at distant compartments. Firstly, we wanted to detect whether transduced cell engraftment contributes to wild type FKRP expression and consequently to α-DG glycosylation in a cell number- dependent manner. WBs confirmed wild type exogenous FKRP expression in the right TAs of transplanted mice for all the conditions, highlighting an increasing trend of protein expression as result of the different cell numbers injected (Fig. 4A–C). Mice injected with 35×103 showed weak bands (Fig. 4A), while transplantation of 75×103 cells (Fig. 4B) determined an increased strong signal that faced a steady point leading to FKRP expression plateau at 100×103 injected cells (Fig. 4C). The FKRP antibody detected a faint band of exogenous FKRP at approximately 60 KDa even in the contralateral TAs thus providing the first evidence of a systemic FKRP distribution as exosome cargo (Fig. 4). FKRP biochemical detection in TAs from not injected mice (Fig. 4) and C57Bl mouse (Fig. 4) confirmed the specificity of the wild type FKRP detection in the contralateral TAs. Since the FKRP-STEM antibody was not able to detect endogenous mutated FKRP (10,14), no bands were observed in the NI TAs (Fig. 4A), while the not mutated form of C57Bl mouse was clearly detectable. Injected TAs muscles were also biochemically analysed for the recovery of α-DG glycosylation. The lowest dose of engineered-satellite cell injection didn’t elicit a significant difference in α-DG glycosylation as compared to untreated muscles (Fig. 4D). On the contrary, 75×103 and 100×103 cell- injected mice TAs showed a slight improvement in α-dystroglycan glycosylation, as observed by the increasing of the signal smear, thus confirming a massive restoration of FKRP function (Fig. 4D and E). IF staining of TA sections showed muscle fiber expression of FKRP in a cell dose-dependent fashion. The 35×103 cell injected mice still display a patchy sarcolemmal expression of FKRP whereas higher cell dose, in particular the condition at 75 ×103 cells, prompted a more uniform and widespread sarcolemmal fluorescence signal (Fig. 5B–D). TAs from animal injected with 100×103 displayed exogenous FKRP expression comparable to the 75×103 transplanted mice (Fig. 5D), whereas 35×103 injection was not sufficient to induce an overall FKRP rescue, rather confined in few myofibers (Fig. 5B). Not injected mice did not show any positive staining (Fig. 5A). Exogenous FKRP perinuclear staining was also found in some muscle fibers (white arrows in Fig. 5C and D inserts). Cell dose-dependent GFP expression (in green in Fig. 5) at cytoplasmic level was found with a marked positive staining in TAs injected with 75 and 100×103 cells (Fig. 5). Moreover, we observed FKRP sarcolemma expression in both GFP+ and GFP- treated muscle fibers (Fig. 5). The staining against the glycosylated epitopes of α-DG showed patchy staining of glycosylated α-DG in the sarcolemma of not injected FKRP L276IKI skeletal muscles, confirming the occurrence of α-DG hypoglycosylation in FKRP L276IKI mice (Fig. 5A’’). Conversely, treated muscles displayed a stronger positive signal as the number of injected cells increased (Fig. 5B’’, C’’ and D’’). The FKRP L276IKI mutant mice exhibit a mild phenotype of muscular dystrophy represented as myofiber regeneration/degeneration, fiber size variability and fibrosis in the later stages of disease progression. Examination of the muscle morphology by H&E staining indicates similar pathological phenotypes between TA skeletal muscles of the untreated and treated FKRP L276IKI, as demonstrated by the presence of areas of necrotic fibers and a number of centrally nucleated fibers (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3).

Figure 4.

Immunoblotting analysis of 12 months-old FKRP L276IKI mice injected muscles. N = 4 FKRP L276IKI mice were transplanted with 35 × 103 (lanes #1, #2, #3, #4) (A, D), N = 5 with 75 × 103 (lanes #5, #6, #7, #8, #9) (B, D) and N = 4 with 100 × 103 (lanes #10, #11, #12, #13) MOI 20 transduced FKRP L276IKI SCs cells (C, E). Both injected (+ lanes) and not-injected (- lanes) TAs were analysed for the expression of FKRP protein. WB analysis of α-dystroglycan (α-DG) glycosylation was evaluated in the TAs of injected muscles (lanes +) (D, E). N = 6 not injected FKRP L276IKI TAs (lanes NI) were analysed as controls (A). C57BL TA was loaded as positive control (lane CTR+) (C).

Figure 5.

Immunofluorescent staining of not injected FKRP L276IKI (FKRP L276IKI NI) TAs and FKRP L276IKI TAs injected with 35 × 103, 75 × 103, 100 × 103 engineered satellite cells (FKRP L276IKI 35K, 75K, 100K). Sections were stained for the expression of exogenous FKRP (in red) (A–D). Fig. 5C and D inserts showed perinuclear exogenous FKRP staining. GFP staining was performed to evidence GFP protein expression and localization (in green) (A’, B’, C’, D’). Merge of FKRP (in red) and GFP (in green) is also reported (A’’, B’’, C’’, D’’). Muscle sections were also analysed for the expression of α-DG glycosylation using IIH6C4-s antibody (in red) (A’’’, B’’’, C’’’, D’’’). Nuclei were stained with Dapi. Images were taken at 40X magnification. Scale bar = 75 μm.

Exosomes-mediated systemic distribution of FKRP protein

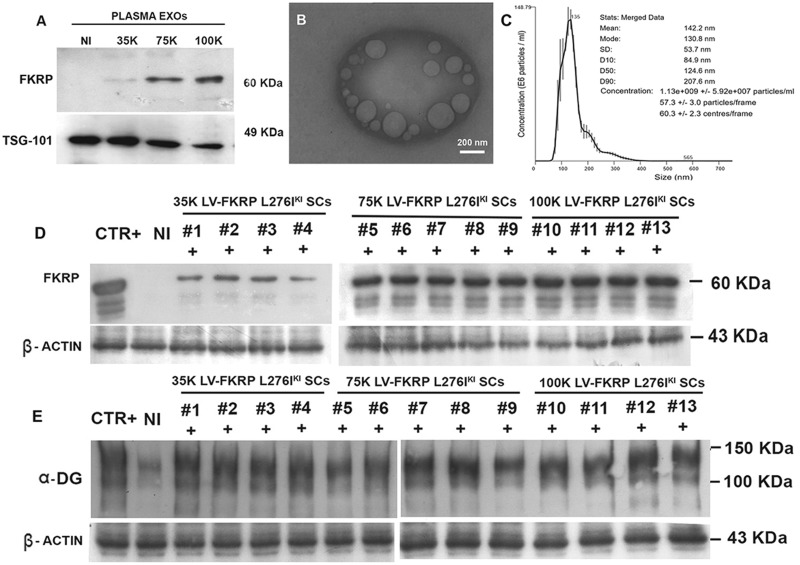

In order to demonstrate the systemic trafficking of exosomes carrying FKRP prompted by the injection of transduced FKRP L276IKI SCs, plasma was collected from all the FKRP L276IKI injected mice, as well as from the not injected ones, for exosome isolation by SEC procedure. Unprocessed plasma and SEC elution plasma fractions were harvested and biochemically analysed. WB showed 60kDa FKRP corresponding bands for unprocessed plasma and plasma isolated exosomes from all the FKRP L276IKI injected mice (Supplementary Material, Fig. S4). No signal was detected in exosome-depleted plasma, suggesting the prime role exerted by exosomes in determining exogenous FKRP protein blood circulation (Supplementary Material, Fig. S4). Further WB characterizations of exosomes isolated from plasma of FKRP L276IKI injected mice and not injected mice have been performed and showed the presence of the exogenous FKRP glycosyltransferase as exosome cargo in a cell number- dependent fashion (Fig. 6A). As expected, FKRP was not detected within the plasma exosomes isolated from the not injected animals (Fig. 6A). The presence of a clear TSG-101 staining confirmed the exosomal origin of all samples (Fig. 6A). Plasma exosomes were also characterized by TEM and NTA analysis. TEM image exhibited the presence of cup-shaped particles, in the range of typical exosome dimensions (mean value 90 nm ± 36.6 nm SD) (Fig. 6B;Supplementary Material, Fig. S2C). Nanosight graph underlines a concentration of 1.13×109 particles/ml, a mean size of 142.2 nm and a mode size of 130.8 nm (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

Western blot analysis of plasma- derived exosomes. Exosomes were isolated from the plasma of 12 months- old FKRP L276IKI mice injected with 35 × 103 (lane 35K), 75 × 103 (lane 75K), 100 × 103 (lane 100K) FKRP L276IKI SCs transduced cells. Plasma was collected immediately before the animal sacrifice. Exosomes were evaluated for the expression of FKRP protein and TSG-101 exosomal marker expression. Plasma-derived exosomes isolated from not injected mice were exploited as control (lane NI) (A). TEM image representative of plasma exosomes morphology (mean size 90 nm ± 36,6 nm SD). Scale bar: 200nm (B). NTA graph representative of plasma-derived exosomes concentration and dimensions (C). Immunoblotting analysis of FKRP L276IKI engineered SCs-injected mice hearts. FKRP expression (D) and α-DG glycosylation (E) were evaluated in N = 4 mice transplanted with 35 × 103 (lanes #1, #2, #3, #4), N = 5 with 75 × 103 (lanes #5, #6, #7, #8, #9), and N = 4 with 100 × 103 (lanes #10, #11, #12, #13) engineered SCs. Not injected FKRP L276IKI heart muscle was used as negative control (lane NI). C57BL heart muscle was exploited as positive control (lane CTR+) (D, E).

The systemic effect of engineered-cell intramuscular transplantation was also evaluated by measuring the exogenous FKRP expression and α-DG glycosylation in the hearts of injected muscles. Heart muscles displayed a stronger positive signal as the number of injected cells increased from 35×103 to 75×103, reaching a plateau between 75×103 and 100×103 injected mice. Similarly to WBs performed for TAs, the specificity of the FKRP band as wild type protein expression elicited by an exosomal source is ensured by the lack of detectable signal in the NI mouse hearts, while the positive control from C57Bl mouse heart showed a clear band corresponding to FKRP protein. As regards α-DG glycosylation, no pronounced differences were found among the three groups of injection, but an increased glycosylation was still observed taking in account the not injected mice and the positive control from C57Bl mouse (Fig. 6D and E).

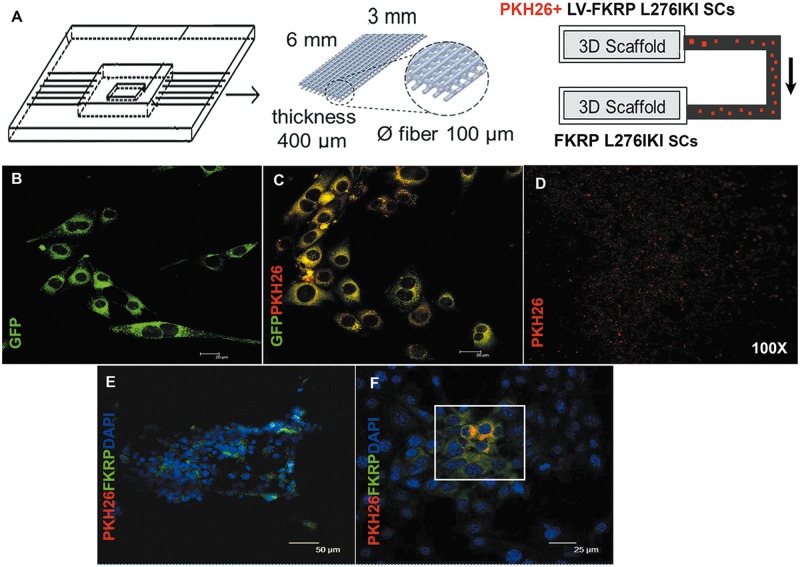

In vitro modelling of dynamic FKRP carrying-exosome trafficking

In order to study the in vivo exosome trafficking dynamic, we reproduced an in vitro model mimicking the blood circulating FKRP shielded and transported within exosomes. Figure 7A shows the in vitro trafficking model of exosomes carrying wild type FKRP, output from infected FKRP L276IKI SCs and moving towards target cells within a miniaturized microfluidic bioreactor. GFP expression detected by confocal fluorescent microscopy confirmed the efficient infection of 1×106 FKRP L276IKI SCs by lentiviral MOI of 20 (Fig. 7B). Infected FKRP L276IKI SCs were also labelled with PKH26 red membrane marker before being seeded into scaffold, determining the diffused signals of GFP and PKH26 within the cell cytoplasm (Fig. 7C;Supplementary Material, Fig. S5A’’). PKH26+ infected FKRP L276IKI SCs were able to continuously release PKH26+ exosomes (Fig. 7D) that were tracked for 8 h within the microfluidic channels by confocal fluorescent microscopy at 100X magnification (Fig. 7D). Once exosomes from infected FKRP L276IKI SCs reached the not infected SCs seeded into the scaffold hosted in the second chamber, they were able to fuse randomly with target cells, conveying the wild type FKRP as cargo protein and favoring its expression. IF analysis performed after 8 h on the not infected FKRP L276IKI SCs, which had been in contact with FKRP carrying- exosomes released from transduced cells, highlighted an exogenous cytoplasmic FKRP positive signal (in green in Fig. 7E and F), mainly confined to cells that internalized exosomes (in red in Fig. 7E and F;Supplementary Material, Fig. S5B’’).

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of the bioreactor. The bioreactor is composed of three scaffolds (6x3 mm, 400µm thickness, 0,6 µm fiber pore size), connected by microfluidic channels. PKH26+ FKRP L276IKI satellite cells were seeded on the first scaffold and secreted PKH26+ exosomes, able to reach not-infected SCs seeded on the second scaffold, running through a microfluidic channel connecting the two chambers (A). IF analysis of infected FKRP L276IKI SCs; GFP signal was detected in the cell cytoplasm (B). PKH26- labelled FKRP L276IKI SCs cells (C). PKH26- exosomes secreted by PKH26- labelled FKRP L276IKI SCs cells (D). Images were taken at 100X magnification. Immunofluorescent analysis of not-infected SCs seeded on the second scaffold. PKH26+ exosomes- (in red) targeted SCs recovered the expression of wild-type FKRP (in green). Nuclei were stained with Dapi (E, F).

Muscle function analysis

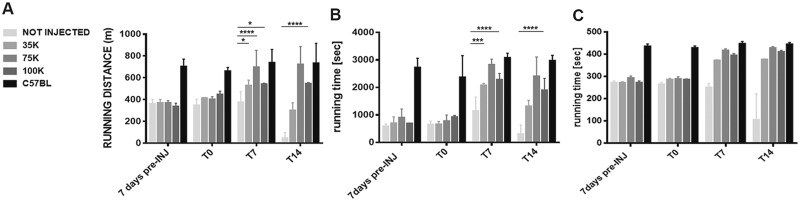

FKRP L276IKI mice intramuscularly transplanted with engineered satellite cells were evaluated by two functional tests, treadmill and rotarod, which are commonly used to determine mice endurance. Treadmill results showed that mice did not receive cell transplant found extremely difficult to accomplish the test until the end of the experimental time points. In general, FKRP L276IKI mice seemed to become familiar with the treadmill after an initial training session (-T7) and are willing to run for the first week (T7), even though they maintained the running distance constantly below 400 meters and the running time around 1000 s. At T14, these mice became unable to sustain downhill treadmill running and showed extreme fatigue, implying an increased sensitivity to exercise-induced fatigue. Conversely, FKRP L276IKI transplanted mice displayed a functional behavior determined by the number of injected LV-FKRP satellite cells and consistent with the FKRP re-expression and α-DG glycosylation level. Overall, FKRP L276IKI treated mice showed a significant increase in distance traveled compared both to the running distance measured before the injections and to FKRP L276IKI untreated animals. Interestingly, FKRP L276IKI mice injected with 75 and 100K cells had a fast positive response to exercise-induced fatigue, both showing an improved trend starting immediately after the injection of LV- FKRP L276IKI SCs, even though the condition of 75K displayed a more marked and noticeable enhancement. 75 ×103 seemed to be the condition determining a real and long lasting increase of the running distance and time, with a leap from 403 meters (averaged running distance) at T0 to 698.7 meters at T7, and up to 724 meters a T14. Interestingly, the trend of the 75×103 transplanted animal running time underwent a fast increase in the first 7 days post injection (T0 averaged running time 779.2 s vs. T7 average running time 2827 s), which settled at T14 around 2411 s. 100×103 transplanted mouse outcomes from the treadmill test showed a slower increase trend that reached the maximum running distance and time at T7, displaying the best performance, followed by plateau level (at T14, averaged running distance: 547 meters; averaged running time: 1898 s) (Fig. 8A and B). FKRP L276IKI mice treated with 35K cells showed instead a higher level of interindividual variability with a slow decrease of the performance. More in details, despite a tendency towards a slight increase of the running distance and time within 7 days after injection, at T14 the 35×103 transplanted mice regressed to functional performances similar to the pre-injection (averaged running distance: 301 meters; averaged running time: 1315 s). The averaged coefficient of variations at 14 days after treatment, calculated considering the baseline level before the cell injection, was -86% for untreated FKRP L276IKI mice, -18% for FKRP L276IKI treated with 35K cells, and respectively +95% and +62% for FKRP L276IKI treated with 75K and 100K infected FKRP L276IKI SCs. With the rotarod test muscle strength, coordination, balance, and condition of FKRP L276IKI mice can be determined. Rotarod functional measures confirmed the poor performances of not injected mice, as well as the cell number-dependent functional improvements of the transplanted FKRP L276IKI mice. On the rotarod, untreated FKRP L276IKI mice hardly ever run for the 300 s. Running performance of not injected FKRP L276IKI mice remains comparable for 2 weeks and started to decrease significantly within T7 and T14. 35×103 transplanted mice showed a marked increase in the first week after the treatment, after which the running time was maintained almost constant throughout the experimental points (T14 averaged running time: 377 s). Similarly, 75 and 100×103 transplanted mice showed an increase in running seconds during the first week after the injection (T7 averaged running time: 418 s and 398 s, respectively) (Fig. 8C). In both cases, even though there were further improvements of the performance at T14 (75 ×103 transplanted mice, averaged running time: 429 s; 100×103 transplanted mice, averaged running time: 411 s) the increase trend remarkably slowed down reaching plateau levels. For both functional measurements, the injected and not injected FKRP L276IKI mouse performances were compared to the outcomes from C57Bl mice (n = 5; treadmill averaged running distance and time: 710 meters and 2788 s; rotarod averaged running time: 437 s). Only the 75×103 injected mice showed an improvement trend ending up in performance comparable to the C57Bl mice at T7 and T14 (Fig. 8A–C).

Figure 8.

Muscle functional tests. Mice endurance was evaluated by treadmill test (A, B) and Rotarod test (C). C57BL mice (N = 5), not injected (N = 6), 35 × 103 (N = 4), 75 × 103 (N = 5), and 100 × 103 (N = 4) MOI 20 transduced FKRP L276IKI SCs- injected mice have been tested at different time points: 7 days before the cell injection (7 days pre-INJ), the day of cells transplantation (T0), and over the course of the time at 7 and 14 days (T7, T14), before the animal sacrifice. Values are means ± SD. P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Discussion

α-DG is a glycoprotein sited on muscle peripheral membranes (15,16), that undergoes glycosyltransferase-mediated N-glycosylation, mucin-type O-glycosylation, O-mannosylation, and an identified phosphorylated O-mannosyl glycan. While the loss of N-linked glycosylation on α-DG has no effects on its ability to bind extracellular ligands, defects in O-linked glycosylation result in α-DG hypoglycosylation and defective binding to laminin, neurexin, and agrin (17), giving rise to congenital disorders named dystroglycanopathies. These latter features can also distinguish a family of muscular dystrophies with a wild clinical phenotype spectrum, ranging from congenital muscular dystrophy (CMD) with brain and eye involvement in severe cases, to limb-girdle muscular dystrophy (LGMD) in milder instances. Mutations in FKRP gene encoding the glycosyltransferase fukutin-related protein determine the occurrence of untreatable limb-girdle muscular dystrophy 2I and MDC1C. The FKRP L276IKI model mimicked the LGMD2I pathology in nearly all aspects, including the major histopathology as well as the biochemical deficiencies (10). Even though no therapeutic efforts have been completely satisfactory, recent encouraging results came out from the overexpression of the glycosyltransferase LARGE (14), and the use of adeno-associated Virus 9 (AVV9)-FKRP that allows the systemic expression of fukutin related protein (10). In line with these findings, we firstly isolated and infected MDC1C CD133+ blood-derived stem cells with lentiviral vector carrying the wild type form of human FKRP gene. FKRP-STEM antibody was used to specifically recognize the exogenous wild type FKRP from the endogenous mutated one (10). This way, we demonstrated the restoration of exogenous isoform of FKRP protein expression in vitro. The lively interest in the novel role of FKRP as glycosyltransferase and the emerging idea of circulating glycosyltransferases (9) has brought out the hypothesis of a cell-mediated release of FKRP in vitro and in vivo (11). In agreement with this expectation, it has been shown that fukutin, another glycosyltransferase responsible for Fukuyama muscular dystrophy, is secreted into culture media (18). Furthermore, considering that the main route for glycosyltransferases to be transported to Golgi is protected and packaged into vesicles, we considered the involvement of exosomes as vesicles carrying FKRP. Exosomes are a homogeneous population of extracellular vesicles attracting particular attention for their ability to deliver cargos to cells in remote locations. In addition to genetic materials (19) and proteins, exosomes can be also enriched in post-translational modifier proteins, such as kinases, phosphatases, and glycosyltransferases, suggesting that FKRP can be effectively carried by exosomes released from transduced cells (20). Interestingly, WB analyses confirmed that the infection of MDC1C CD133+ stem cells and FKRP L267IKI SCs prompted the release of exosomes conveying the wild type form of FKRP. These results reasonably supported the hypothesis that in vivo exosomes can equally traffic and maintain the ability to deliver the glycosyltransferase to receiving cells. To demonstrate the in vivo role of exosomes carrying the FKRP protein and in order to present the potential clinical application of LV-FKRP cell therapy, we performed in vivo experiments in the FKRP L267IKI mouse model of the LGMD2I (3). We carried out an autologous transplantation by intramuscularly injecting three different doses of LV-FKRP satellite cells into the TA muscles of FKRP L267IKI recipients. The need for an autologous transplantation was due to the absence of an immunodeficient FKRP L267IKI animal model. The successful rescue of the exogenous and functional FKRP protein expression and the restoration of the α-dystroglycan glycosylation were demonstrated both by WB and IF analyses. FKRP, as well α-DG showed a cell-dose dependent response in the injected FKRP L267IKI TAs: 35×103 LV-FKRP SCs was sufficient to determine a weak FKRP recovery in the injected TAs, but it was inadequate to prompt a clear increase of glycosylation; 75×103 and 100×103 SC injection induced both marked FKRP signals and enlarged α-DG smears, corresponding to enhanced glycosylation levels. Indeed, it seems that there is a functional window for an effective recovery of FKRP expression and the consequent α-DG glycosylation: 35×103 SCs represented a dose below the bare minimum, while 100x 103 SCs was a plateau dose beyond that an additional contribution of LV-FKRP cells did not further improve the FKRP and α-DG expression.

Interestingly, unless previous studies localized FKRP expression in resident Golgi and endoplasmic reticulum, as punctuate dots in the cytoplasmic compartments of myofibers (3), we have detected FKRP positive signal at the sarcolemma level. This result is in line with previous studies showing a co-localization with α-DG (21) and suggesting that FKRP activity is required at sarcolemma for normal muscle function. Moreover, we observed two different types of staining: the first consisting in FKRP+ sarcolemma of cytoplasm GFP negative muscle fibers; the second seeing cytoplasm GFP+ fibers, together with the presence of perinuclear FKRP+ cells. These results would imply two different mechanisms of FKRP expression, one mediated by satellite cell fusion, and the other by exosome release. The staining against the glycosylated epitopes of α-DG showed a stronger positive sarcolemma signal in treated animals as the number of injected cells increased. These observations confirmed that the level of functionally glycosylated α-DG in the injected FKRP L276IKI mice is linked to FKRP expression. Additionally, we demonstrated that not only engineered FKRP L276IKI SCs secreted in vitro FKRP-positive exosomes expressing TSG-101 marker, but also we found FKRP-exosomes circulating in the plasma of transplanted FKRP L276IKI mice. Of note, exosome-depleted plasma of FKRP L267IKI SCs injected mice did not show the expression of FKRP, further suggesting that blood circulation of exogenous FKRP protein is determined by exosomes systemic trafficking. The presence of FKRP-exosomes promoted systemic FKRP expression and improved muscle recovery of FKRP L276IKI transplanted mice. In particular, exosome boosted systemic FKRP expression enhances FKRP expression and α-DG glycosylation in the hearts of intramuscularly transplanted FKRP L276IKI mice. Since the heart is one of the most compromised compartments in the FKRP L276IKI animal model (10), implicating a low endurance and performances for exercises, the results obtained from treadmill and rotarod assessments can be interpreted as a general amelioration of cardiac functionality, aerobic capacity and motor recovery. Although treated FKRP L276IKI mice resulted in increased rotarod performance and resistance to eccentric contractions, histopathology was not different from untreated FKRP L276IKI mice. It is likely that LV-FKRP SCs may continually deliver FKRP positive exosomes to the mouse hearts, exerting a cardioprotective role. The cellular and molecular mechanisms of exosome membrane fusion to the plasma membrane of specific target cells are still undetermined, even though the aspects of their interactions are starting to emerge. Once released, exosomes can slide on target cell surfaces, reduce their movements and finally bind in an adhesion molecules dependent manner (i.e. integrin) (22). Interestingly, it has been demonstrated that fractions of exosomes undergo a cell uptake via different forms of endocytosis for releasing their cargo into the cytoplasm, while other exosomes may associate and fuse with the plasma membrane. This process determines the ensuing insertion of exosome membrane in the target cell plasma membrane, where either they dock or eventually discharge to the cytosol their luminal cargo molecules. From our point of view, FKRP immunofluorescence staining of injected FKRP L276IKI muscle likely mirrors the latter exosomal fusion pathway, as demonstrated by the localization of positive FKRP signal around muscle membranes. Therefore, it is reasonable to think that exosome carrying FKRP, upon sliding and fusion with muscle fiber, would remain stuck at the sarcolemma level may be due to the specificity of FKRP function in muscle tissue. There are also fractions of exosomes that, once released in the extracellular space, continue to travel through extracellular fluid to reach biological fluids (i.e. blood), and then towards body sited located far from their cell origin (23). To investigate the cell- to cell transmission of systemic exosomal FKRP, we took advantage of miniaturized microfluidic system allowing for the culture of two cell populations in two separate but connected chambers. The presence of an optical transparent tubing connecting the chambers guaranteed the direct observation of FKRP trafficked by exosomes from LV-FKRP L276IKI SCs on one side (exosomal source) to not infected FKRP L276IKI cells on the other side (target cells). The selective exosome uptake on only one side was ensured by the application of a unidirectional medium flow, simulating a systemic circulation directing exosomal FKRP from the blood to distal compartment. By using this miniaturized microfluidic system, we confirmed that FKRP can be continuously and directionally transmitted via circulating exosomes towards target cells, where they can fuse and induce a fast expression of functional exogenous FKRP protein. The short timing (24 h) required in vitro for exosome-mediated FKRP restoration in FKRP L276IKI SCs are consistent with the rapid systemic exosome contributions (15 days) to FKRP expression, α-DG glycosylation and general amelioration. However, further investigations would be necessary to better investigate the long-term beneficial effects and to unravel mechanisms of in vivo exosomal FKRP spreading and tissue selectivity. Together, these data demonstrated that muscular dystrophies associated with α-DG glycosylation defects can be treated by a combined gene and cell therapy aimed at restoring FKRP expression and function. Exosomes carrying FKRP can also unexpectedly sustain these strategies, offering the possibility to achieve systemic and general outcomes and to boost the effect of an intramuscular injection.

Materials and Methods

Cell cultures

Isolation and FACS characterization of MDC1C blood-derived CD133+ stem cells. CD133+ blood-derived stem cells were isolated from a MDC1C patient affected by two heterozygous mutations in FKRP gene: c518T > G and c1087G > C, after obtaining related informed consent and according to Guidelines by the Committee on the Use of Human Subjects in Research at Policlinico Hospital of Milan. Blood sample was processed through a MACS magnetic column (Miltenyi Biotec; Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), as previously described (24). CD133+ purity was evaluated by FACS analysis. For three-color flow cytometric analysis, at least 1×105 cells from peripheral blood were incubated with the following monoclonal antibodies (MoAbs): anti-CD133/2-phycoerythrin (PE) Miltenyi Biotec; Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), anti-CD34-Allophycocyanin (APC) and anti-CD45-FITC (Becton Dickinson, Immunocytometry Systems; San Diego, California, USA). For each MoAb, an appropriate isotype-matched mouse immunoglobulin was used as a control. After staining, performed at 4 °C for 20 min, cell suspensions were washed in PBS containing 1% heat inactivated foetal calf serum (FCS) (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific; Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) and 0.1% sodium azide. Cells were analysed using a FC500 Cytomics flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter; Brea, California, USA) and 2.1 CXP software. Each analysis included at least 15,000–30,000 events. A light-scatter gate was set up to eliminate cell debris from the analysis. The percentage of CD133+ cells present in the sample was assessed after correction for the percentage of cells reactive with the isotype control.

Isolation, FACS characterization and myogenic differentiation of FKRP L276IKI satellite cells. Satellite cells (SCs) were obtained from FKRP L276IKI new born mice as previously described (25). FKRP L276IKI mice were developed by Professor Qilong Lu (McColl-Lockwood Laboratory for Muscular Dystrophy Research, Neuromuscular/ALS Center, Carolina Medical Center, Charlotte, North Carolina, USA). FKRP L276IKI strain was created by knocking in the human mutation (nucleotide C826 to A) into the coding sequence of the mouse FKRP gene, resulting in amino acid replacement leucine 276 to isoleucine (L276I). Animals were housed in Charles River Laboratories (Calco, Italy) and provided with unlimited supply of drinking water and food. Briefly, hind limb muscles were washed in 1X phosphate-buffered saline (PBS: 8g/l NaCl, 0.2g/l KCl, 1.44g/l Na2HPO4, 0.24g/l KH2PO4 in distilled water; pH7.4) for blood cleansing. Muscles were placed in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) with penicillin/streptomycin (100 μl/10ml) and fungizone (120 μl/10ml) for a manual connective and adipose tissue, blood vessel and nerve bundle removal under a dissection microscope. Subsequently, muscular tissue was mechanically homogenized and enzymatically digested for 30 min at 37 °C with a solution of collagenase V (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, Missouri, USA) 0.11 mg/ml, dispase (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific; Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) 0.45 mg/ml, Dnase (Roche; Basilea, Switzerland) 0.01 mg/ml in 12 ml of Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS). The mixture was filtered with a cell strainer (70µm), and incubated for 15 min. Cells were centrifuged at 458g for 20 min at RT. Finally, the pellet was suspended in DMEM at 20% of FBS with antibiotics, 1% embryonic extract chicken (CEE) (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific; Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) and 2% horse serum (HS) (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific; Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). Suspended cells were counted by Trypan blue (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, Missouri, USA) and plated at a final density of 380 cellule/cm2 in collagen-treated dishes at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Plates were incubated overnight and fresh medium was then replaced. SCs were phenotypically characterized by cytofluorimetric analysis, as already described. SCs were incubated with Pax7 (Hybridoma Bank; Lowa, USA) and CD29-FITC (Milteni Biotech; Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). For the first staining, SCs were fixed with 1.5% paraformaldehyde, followed by an overnight incubation with the primary antibody (dilution 1:10) at 4 C° and by an incubation with monoclonal anti-mouse 488 Alexa Fluor secondary antibody (Molecular Probe, Thermo Fisher Scientific; Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) (dilution 1:100). CD29 was detected incubating cells at 4 °C for 20 min. Anti-7-alpha-actin-mycin D (7-AAD) (Becton Dickinson, Immunocytometry Systems; San Diego, California, USA) staining was used to evaluate cell vitality. After staining, performed at 4 °C for 20 min, cell suspensions were washed in PBS containing 1% heat inactivated FBS and 0.1% sodium azide. Cells were analysed using a FC500 cytomics flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter; Brea, California, USA) and 2.1 CXP software. Each analysis included at least 15,000–30,000 events. In vitro immunofluorescence staining (IF) was also performed to assess the SCs myogenic differentiation. After reaching a confluence of 90%, the growing medium was replaced with DMEM 2% HS (differentiation medium), to induce SC myogenic differentiation in serum starvation conditions. Briefly, cells were fixed in formaldehyde 4% for 10 min at room temperature, and then incubated in blocking solution (5% of FBS, 2% of HS, 0.3% TRITON in PBS1X) for 30 min. SCs were incubated overnight with Pax7 antibody (dilution 1:20) (Hybridoma bank; Lowa, USA) at 4 °C, followed by a staining with the α-mouse biotinilated (dilution 1:100) for 30 min and with Cy3-streptavidin-conjugated secondary antibody (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, Missouri, USA) for 1 h. Subsequently, SCs were incubated with desmin antibody (diluted 1:50) (Abcam; Cambridge, UK) for 1 h and developed with anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 antibody (Molecular Probe, Thermo Fisher Scientific; Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) (diluted 1:100). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride, Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, Missouri, USA). SCs were analysed by IF at three different time points: T0, before inducing myogenic differentiation, T7 and T14, respectively 7 and 14 days in differentiation conditions. Images were captured with Leica TCS SP2 confocal microscope.

Transduction of MDC1C CD133+ blood-derived stem cells and FKRP L276IKI satellite cells

Lentiviral vector design. The lentiviral vector was produced by AMS Biotechnology Company (AMSBIO; Abingdon, UK) as previously described (26). The target gene (human FKRP: NM_001039885.2) was obtained from a gene bank and it was sub-cloned into expression lentivector via Eco cloning technology (non-enzyme based cloning technique). The target gene was expressed under the CMV early enhancer/chicken b-actin [CAG] promoter. GFP-Puromycin reporter gene was expressed under a Rous sarcoma virus [Rsv] promoter. Thus, the target and reporter genes were independently expressed by two different promoters. Infected cells were selected using Puromycin linked to GFP. No tag was added to the expressed gene. Empty lentiviral vector with only Rsv-GFP puro was used as a control.

Titer of viral preparation. To establish the titer of viral preparation, 105 CD133+ blood derived stem cells were transduced with 5 × 105 ip, 106 ip, 2 × 106 ip in a 96-well plate (MOI of 5, 10, 20, respectively) immediately after cell isolation. Viral transduction was performed in 100 μl of DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS. 24-h post-transduction, fresh medium/well was added and cells were maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Each sample was evaluated in triplicate in three independent experiments. The transduction efficiency was evaluated after 6 days both by FACS –as % of GFP positive cells in 488 nm emission wavelengths – and by green fluorescence cell count through Fiji Analyse Particles function (Image J). Cells transduced with higher MOI 20 have been also examined for impaired viability due to undesirable virus cytotoxic effects. Trypan Blue Exclusion was performed every 5 days for 30 days on transduced and not transduced MDC1C CD133+ blood-derived stem cells, as previously described (27). Different lentiviral MOI effects on FKRP L276IKI satellite cells were tested. On this purpose, 105 cells/well were seeded in a 48 wells plate and transduced with different lentivirus MOIs: 10, 20, and 40. Not infected FKRP L276IKI satellite cells were used as negative control. Infected and not infected satellite cell proliferation has been tested every 5 days by Trypan Blue Exclusion assay for 25 days (28). We have also tested the effects of lentivirus vector carrying only the GFP expression cassette (RSV.GFP) to rule out the possibility of GFP cytotoxicity. Trypan Blue Exclusion Assay was performed on FKRP L276IKI satellite cells transduced with 10, 20, and 40 MOIs of the empty vector, as already described. Myogenic differentiation of infected (either with the vector carrying wild type FKRP or with empty vector) FKRP L276IKI satellite cells was induced in serum starvation culture conditions to detect unwanted MOI-related detrimental effects. Fusion Index (FI) was calculated after 7 days as the number of nuclei in myotubes divided by the total number of nuclei. In order to visualize and count myotubes and nuclei, differentiated SCs were washed with PBS and fixed in ethanol 80% for 3 min. Cells were then stained with desmin antibody (1:50) (Abcam; Cambridge, UK) for 1 h and counterstained with DAPI for nuclei visualization. Total cell nuclei and nuclei within myotubes were counted using the NIH ImageJ software. A muscle cell containing 3 or more nuclei was considered as a myotube, as previously defined (29).

Western blot analysis and immunofluorescence staining of in vitro cell cultures. MDC1C CD133+ blood derived stem cells and FKRP L276IKI satellite cells were harvested 7 days post infection and directly lysed using NP40 lysis buffer (20mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8), 140mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, and 0.5% NP40, 1mM phenylmethylsulfonil fluoride) and complete protease inhibitor mixture (Roche; Basilea, Switzerland). Briefly, cell lysates were passed through a 30.5-gauge needle, incubated at 4 °C for 15 min, and centrifuged at 12000g for 15 min at 4 °C. Total protein concentration was determined according to Lowry’s method. 30 μg of samples were resolved on 10% polyacrylamide gel for wild type FKRP antibody or, alternatively, on 8% polyacrylamide gel for α-DG detection and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad; Hercules, California, USA). FKRP-5643 (FKRP-STEM) antibody was gently supplied by Dr Qilong Lu and exploited for all the immunofluorescence and biochemical analyses described in this work (McColl Lockwood Laboratory for Muscular Dystrophy Research, Neuromuscular/ALS Center Carolinas Medical Center, Charlotte, North Carolina, USA). FKRP-STEM is a rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against the stem region (amino-acid residues 29–130) of the mouse FKRP, which is not able to detect a mutant isoform, but only the wild type FKRP. Therefore, WB bands and positive IF signal pertain to lentivirus mediated FKRP rescue. The filters were saturated in blocking solution (10 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 154 mM NaCl, 1% BSA, 10% horse serum, and 0.075% Tween-20). The rabbit anti-FKRP antibody (1:600) was incubated overnight at 4 °C. Mouse anti-α-DG (IIH6-C4-5, dilution 1:50) (Hybridoma Bank; Lowa, USA) was used to detect the level of -α-DG-glycosylation. Anti-β-actin (1:600) (Sigma Aldrich; St. Louis, USA) was detected as housekeeping protein. Detection was performed with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (Dako; Glostrup, Denmark) (1 h at room temperature), followed by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) development (GE Healthcare; Little Chalfont, UK). Pre-stained molecular weight markers (Bio-Rad Laboratories) were run on each gel. Bands were visualized by autoradiography using Amersham Hyperfilm™ (GE Healthcare; Little Chalfont, UK). Densitometric analysis was performed using ImageJ software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/). For all the experiments not transduced MDC1C CD133+ blood derived stem cells and FKRP L276IKI satellite cells were used as controls. IF staining was performed on MOI 20 infected FKRP L276IKI SCs to detect GFP and exogenous FKRP expression. Satellite cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 5 min, pre-incubated blocking solution (1% BSA, 0.05% Tween, 5% FBS in PBS1X) for 30 min and stained for 2 h with rabbit anti FKRP-STEM (dilution 1:50) and mouse anti-GFP (dilution 1:500) (Abcam; Cambridge, UK) antibodies. Monoclonal anti-rabbit 594 and monoclonal anti-mouse 488 (Molecular Probe, Thermo Fisher Scientific; Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) were added at a dilution of 1:100 in PBS for 1 h. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, USA). Images were captured with Leica TCS SP2 confocal microscope (Leica, Germany).

In vitro exosome carrying FKRP release from transduced MDC1C CD133 + blood derived stem cells and FKRP L276IKI satellite cells

Exosome isolation and protein quantification from cell supernatants. Cell culture media (CM) were harvested from engineered CD133+ blood-derived stem cells and FKRP L276IKI satellite cells after 24h in serum-free conditions and immediately centrifuged at 2000 g for 30 min to remove cell debris. 15 ml of supernatants from each condition were then concentrated by Amicon Ultra 10k MWCO filters (Merck Millipore; Darmstadt, Germany) to a final volume of 500 μl. Subsequently, size exclusion chromatography (SEC) was performed, exploiting the qEV Size Exclusion Columns (30). Briefly, the 500 µl of concentrated supernatants were loaded on columns and elution was performed using PBS 1X as elution buffer. 0.5 ml fractions of the sample were collected. The protein concentration of each fraction was measured by microBCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Waltham, Massachusetts, USA).

Exosome characterization. To characterize exosomes by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis, the pellet was resuspended in PBS 1X and 5µl were directly loaded onto formvarcarbon-coated grids. (31,32). The evaluation of vesicle absolute size distribution was performed using NanoSight LM10 (Malvern, UK). The NTA measurement conditions were settled: temperature 23.75 ± 0.5 °C; viscosity 0.91 ± 0.03 cP, frames per second 25, measurement time 60s. N = 3 recordings were performed for each sample (31,32). To perform FACS analysis, 2 µg of exosomes were incubated for 20 min at 4 °C with CD63-PE-vio770 (Miltenyi Biotech; Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), and CD81-PE (Beckman Coulter; Brea, California, USA) antibodies. After that, the mix was added with 10 µl of magnetic CD63-conjugated beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific;Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) and incubated overnight at 4 °C under gentle rotation. After staining, exosome suspensions were washed in PBS containing 1% heat inactivated exosome-depleted foetal calf serum and 0.1% sodium azide. The cytometric analysis was performed on a FACS Cytomic FC 500. Each analysis included at least 100000 events. The analysis was conducted using CXP 2.1 software. For WB analysis on exosomes, 5 µg of fraction 9-enriched exosomes were mixed with Laemmli sample buffer (62.5 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8; 2% SDS; 5% 2-mercaptoethanol, glycerol 10%, Bromophenol Blue 0.004%), boiled at 65 °C for 10 min and resolved on 10% polyacrylamide gel, transferred to supported nitrocellulose membranes, and the filters were saturated in blocking solution (10 mM Tris pH 7.4, 154 mM NaCl, 1% BSA, 10% horse serum, and 0.075% Tween-20). Anti-TSG 101 (1:200) (Abcam; Cambridge, UK), anti-Ago2 (1:200) (Proteintech, Europe; Manchester, UK), and anti FKRP-STEM (1:600) antibodies were incubated overnight at 4 °C in the blocking solution or, alternatively, exploiting the Signal-boost Immunoreaction Enhancer Kit (Calbiochem; Inalco, Italy), when the enhancement of the signal was required. Detection was performed with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies, followed by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) development. Prestained molecular weight markers were run on each gel. Bands were visualized by autoradiography using Amersham Hyperfilm™. Images of bands were obtained using the CanoScan LiDE60 Scanner and the Canon ScanGear Software. Densitometric analysis was performed using ImageJ software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/).

In vitro modelling of dynamic FKRP carrying- exosome trafficking. In order to mimic the FKRP trafficking within exosomes, a miniaturized, microfluidic bioreactor was employed and set up as described elsewhere with minor modifications (33). The dynamic system is optically transparent and composed of three independent chambers, each hosting one independent polystyrene scaffold for cell culture (dimensions 6 × 3 × 0.4 mm, 3D Biotek; Hillsborough, NJ, USA). These scaffolds are composed of four layers of fibers (100 μm in diameter, with a pore size of 300 μm) shifted of 150 μm with respect to the adjacent (Fig. 4A).

Three independent microfluidic channels, directly machined in the bioreactor body, perfuse the chambers. Scaffolds were pre-conditioned in sterile conditions with cell culture medium, as already described (34). The day after 106 FKRP L276IKI satellite cells transduced with LV-MOI 20 were labelled with PKH26 red marker, according to the manufacturer’s protocol, in order to release PKH26+ exosomes (35) and plated in 400 μl into one scaffold. Likewise, another scaffold was seeded with not labelled 105 FKRP L276IKI satellite cells. The constructs were then maintained at 37 °C overnight to let cells adhere, and then they were moved into two independent bioreactor chambers, which were sealed by magnetic covers. DMEM 10% FCS was pumped with a unidirectional flow rate of 5 μl/min into the first chamber hosting transduced FKRP L276IKI satellite cells by a multi-channel programmable syringe pump (PHDULTRA, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA) in a gas permeable tubing system (0.03′′ ID × 0.065′′ OD, Silastic Tubing, Cole-Parmer, Vernon Hills, IL, USA). The outward medium, enriched with exosomes released from PKH26+ infected FKRP L276IKI satellite cells, entered the second chamber containing FKRP L276IKI satellite cells, and thereafter it was collected in a reservoir. The experiment was carried out for 8 h, and then the scaffolds were transferred into a 48-wells plates and treated for IF staining of exosome-mediated FKRP expression. Scaffolds containing FKRP L276IKI satellite cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min, pre-incubated with blocking solution (1% BSA, 0.05% Tween, 5% FBS in PBS1X) for 1 h and stained overnight at 4 °C with rabbit anti FKRP-STEM antibody in blocking solution (diluted 1: 50). Monoclonal anti-rabbit 488 (Molecular Probe; Thermo Fisher Scientific; Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) was added at a dilution of 1:100 in PBS for 1 h. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, USA) and images were captured with Leica TCS SP2 confocal microscope.

In vivo transplantation of LV-FKRP L276IKI satellite cells into FKRP L276IKI mouse models

For in vivo transplantation, 12 months old FKRP L276IKI mice were anesthetized with 2% avertin (0.015 mL/kg) and injected in the tibialis anterior (TA) with 35×103 (N = 4), 75×103 (N = 5), and 100×103 (N = 4) FKRP L276IKI satellite cells transduced with MOI 20 in 100 μl of PBS, using a 33G Hamilton syringe (Hamilton; Reno, Nevada, USA). N = 6 mice were not injected and used as control. Two weeks later, the mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation.

Immunofluorescence and WB analyses. Both TA muscles were removed from injected and not-injected FKRP L276IKI mice and frozen in liquid nitrogen–cooled isopentane for IF staining, or directly lysed in specific buffer for biochemical analysis. For the evaluation of systemic distribution of FKRP protein in distal compartments, hearts (HT) were also removed and processed for WB analyses.

For IF, serial TA muscle sections of 12 µm thickness were cut by cryostat (Leica CM1850). Staining of sections was performed for FKRP with rabbit anti FKRP-STEM antibody (diluted 1: 50), and mouse anti-GFP (dilution 1:500) (Abcam; Cambridge, UK). Tissue sections were also stained with mouse anti-Dystroglycan IIH6-C4-5 (1:50) (Hybridoma Bank; Lowa, USA), directed against glycan epitopes of α-DG. Monoclonal anti-rabbit 594, monoclonal anti-mouse 594 and monoclonal anti-mouse 488 (Molecular Probe; Thermo Fisher Scientific; Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) were added at a dilution of 1:100 for 1 h. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, USA) and images were captured with Leica TCS SP2 confocal microscope. For WB analyses, Tas and HTs from all the FKRP L276IKI mice, injected and not injected, were homogenized in NP40 lysis buffer using a POTTER S Homogenizer (B. Braun Biotech International-Sartorius group; Melsungen, Germany). Sample were then incubated at 4 °C for 15 min and finally centrifuged at 12000g for 15 min at 4 °C. Total protein concentration was determined according to Lowry’s method. 30 μg of each sample was loaded on 10% polyacrylamide gel for wild type FKRP detection (FKRP-STEM antibody, dilution 1:600), and on 8% polyacrylamide gel for α-DG detection (IIH6-C4-5, dilution 1:50) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad; Hercules, California, USA). Anti-α-actin (1:600) (Sigma Aldrich; St. Louis, USA) was detected as housekeeping protein. For WB analyses Tas and HTs from C57Bl mice were considered as positive controls.

Histopathology of FKRP L276IKI muscle tissues. Frozen TA muscles from injected and not-injected FKRP L276IKI mice and cut by cryostat (Leica CM1850) in 12 µm thickness muscle sections for Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) (Sigma Aldrich; St. Louis, USA). TA from C57Bl mouse was used as a control.

Isolation of circulating plasma exosomes carrying FKRP protein from injected FKRP L276IKI mice. Immediately before sacrifice, 300 μl of blood were collected into EDTA-coated tubes from the submandibular vein of the 35×103, 75×103, and 100×103 engineered satellite cells injected FKRP L276IKI mice. The whole blood was then centrifuged at 1200g for 10 min at 4 °C to separate plasma. Plasma was transferred to a 1.5 ml tube and stored at – 80 °C until use. Exosomes were isolated from the plasma using SEC device (qEV IZON Science; Scheafer, South East Europe) after diluting samples 1:2 with filtered PBS1X. According to the manufacturer’s instructions, the first six eluted fractions are considered the “void volume” and discharged, while exosomes were predominantly found in fractions 7, 8, and 9. The last elution volumes, considered depleted from exosomes, were stored and analysed to determine the presence of free FKRP circulation not mediated by exosomes. The plasma exosome expression of wild type FKRP was evaluated throughout western blot analyses using anti FKRP-STEM antibody, as previously described for supernatant exosomes derived from MDC1C CD133+ blood-derived cells and FKRP L276IKI SCs. For FKRP detection of mouse plasma, 5μl of samples were directly mixed with Laemmli buffer and processed as already described.

Functional measurements. Treadmill and Rotarod tests were performed on all the mice injected with 35 (n = 4), 75 (n = 5), and 100 (n = 4) ×103 engineered FKRP L276IKI satellite cells for measuring the mice endurance. N = 6 FKRP L276IKI not injected mice and n = 5 age-matched C57Bl mice were used as controls. Four different time points were evaluated: 7 days before cell injection, the transplantation day (T0), and 7 and 14 days after (T7 and T14), after that the animals were sacrificed. Treadmill was conducted as a simple motor exercise as reported by (10). Briefly, animals were placed on a motorized treadmill (Harvard Apparatus; Holliston, Massachusetts, USA) to run with an upward angle of 15° at a rate of 15m/min. In order to account for the high inter-individual variability, running meter outcomes from treated and untreated groups at T14 were also normalized to pre-exercise (7 days before the cell treatment) results for each FKRPL276IKI mouse, considered as “baseline level”. The data for each group are now presented as percentage of averaged changes in running meters, calculated as [(Activity at T14/Activity 7days before the injections) × 100] – 100.The measurement was stopped when the mice spent 5 s blocked on the shock grid. Rotarod is a relatively complex motor training procedure, testing balance and coordination aspects of motor performance. Mice were placed on the rod that accelerated from 5 to 45 rotations/min within 15 s. When a mouse ran for 500 s without falling from the rod, the test session was ended. Mice that fell off within 500 s were given a maximum of two more tries. The longest running time was used for the analysis.

Statistical analysis

Prism 5.0 (Graphpad) statistical analysis was used. Statistical comparisons were based on Student's t-test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey post-hoc test for pairwise comparisons. A confidence level of 95% was considered significant. P-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material is available at HMG online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

A special thank goes to Prof. Davide Prosperi and his group at Università degli Studi di Milano-Bicocca, for NTA expertise. All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed.

Conflict of Interest statement. None declared.

Funding

Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by Fondazione Opsis Onlus.

References

- 1. Mercuri E., Muntoni F. (2013) Muscular dystrophy: new challenges and review of the current clinical trials. Curr. Opin. Pediatr., 25, 701–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kanagawa M., Kobayashi K., Tajiri M., Manya H., Kuga A., Yamaguchi Y., Akasaka-Manya K., Furukawa J., Mizuno M., Kawakami H.. et al. (2016) Identification of a Post-translational Modification with Ribitol-Phosphate and Its Defect in Muscular Dystrophy. Cell Rep., 14, 2209–2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Xu L., Lu P.J., Wang C.H., Keramaris E., Qiao C., Xiao B., Blake D.J., Xiao X., Lu Q.L. (2013) Adeno-associated virus 9 mediated FKRP gene therapy restores functional glycosylation of alpha-dystroglycan and improves muscle functions. Mol. Ther., 21, 1832–1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Inamori K., Hara Y., Willer T., Anderson M.E., Zhu Z., Yoshida-Moriguchi T., Campbell K.P. (2013) Xylosyl- and glucuronyltransferase functions of LARGE in alpha-dystroglycan modification are conserved in LARGE2. Glycobiology, 23, 295–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brockington M., Blake D.J., Prandini P., Brown S.C., Torelli S., Benson M.A., Ponting C.P., Estournet B., Romero N.B., Mercuri E.. et al. (2001) Mutations in the fukutin-related protein gene (FKRP) cause a form of congenital muscular dystrophy with secondary laminin alpha2 deficiency and abnormal glycosylation of alpha-dystroglycan. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 69, 1198–1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brown S.C., Torelli S., Brockington M., Yuva Y., Jimenez C., Feng L., Anderson L., Ugo I., Kroger S., Bushby K.. et al. (2004) Abnormalities in alpha-dystroglycan expression in MDC1C and LGMD2I muscular dystrophies. Am. J. Pathol., 164, 727–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gerin I., Ury B., Breloy I., Bouchet-Seraphin C., Bolsee J., Halbout M., Graff J., Vertommen D., Muccioli G.G., Seta N.. et al. (2016) ISPD produces CDP-ribitol used by FKTN and FKRP to transfer ribitol phosphate onto alpha-dystroglycan. Nat. Commun., 7, 11534.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Praissman J.L., Willer T., Sheikh M.O., Toi A., Chitayat D., Lin Y.Y., Lee H., Stalnaker S.H., Wang S., Prabhakar P.K.. et al. (2016) The functional O-mannose glycan on alpha-dystroglycan contains a phospho-ribitol primed for matriglycan addition. eLife, 5, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lee-Sundlov M.M., Ashline D.J., Hanneman A.J., Grozovsky R., Reinhold V.N., Hoffmeister K.M., Lau J.T. (2017) Circulating blood and platelets supply glycosyltransferases that enable extrinsic extracellular glycosylation. Glycobiology, 27, 188–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Qiao C., Wang C.H., Zhao C., Lu P., Awano H., Xiao B., Li J., Yuan Z., Dai Y., Martin C.B.. et al. (2014) Muscle and heart function restoration in a limb girdle muscular dystrophy 2I (LGMD2I) mouse model by systemic FKRP gene delivery. Mol. Ther., 22, 1890–1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lu P.J., Zillmer A., Wu X., Lochmuller H., Vachris J., Blake D., Chan Y.M., Lu Q.L. (2010) Mutations alter secretion of fukutin-related protein. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1802, 253–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Van Deun J., Mestdagh P., Sormunen R., Cocquyt V., Vermaelen K., Vandesompele J., Bracke M., De Wever O., Hendrix A. (2014) The impact of disparate isolation methods for extracellular vesicles on downstream RNA profiling. J. Extracell. Vesicles, 3, 10.3402/jev.v3.24858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lotvall J., Hill A.F., Hochberg F., Buzas E.I., Di Vizio D., Gardiner C., Gho Y.S., Kurochkin I.V., Mathivanan S., Quesenberry P.. et al. (2014) Minimal experimental requirements for definition of extracellular vesicles and their functions: a position statement from the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles, 3, 26913.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vannoy C.H., Xu L., Keramaris E., Lu P., Xiao X., Lu Q.L. (2014) Adeno-associated virus-mediated overexpression of LARGE rescues alpha-dystroglycan function in dystrophic mice with mutations in the fukutin-related protein. Hum. Gene Ther. Methods, 25, 187–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ervasti J.M., Sonnemann K.J. (2008) Biology of the striated muscle dystrophin-glycoprotein complex. Int. Rev. Cytol., 265, 191–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya O., Ervasti J.M., Leveille C.J., Slaughter C.A., Sernett S.W., Campbell K.P. (1992) Primary structure of dystrophin-associated glycoproteins linking dystrophin to the extracellular matrix. Nature, 355, 696–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Herbst R., Iskratsch T., Unger E., Bittner R.E. (2009) Aberrant development of neuromuscular junctions in glycosylation-defective Large(myd) mice. Neuromuscul. Disord., 19, 366–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kobayashi K., Nakahori Y., Miyake M., Matsumura K., Kondo I. E., Nomura Y., Segawa M., Yoshioka M., Saito K., Osawa M.. et al. (1998) An ancient retrotransposal insertion causes Fukuyama-type congenital muscular dystrophy. Nature, 394, 388–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moldovan L., Batte K., Wang Y., Wisler J., Piper M. (2013) Analyzing the circulating microRNAs in exosomes/extracellular vesicles from serum or plasma by qRT-PCR. Methods Mol. Biol., 1024, 129–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Martins V.R., Dias M.S., Hainaut P. (2013) Tumor-cell-derived microvesicles as carriers of molecular information in cancer. Curr. Opin. Oncol., 25, 66–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Beedle A.M., Nienaber P.M., Campbell K.P. (2007) Fukutin-related protein associates with the sarcolemmal dystrophin-glycoprotein complex. J. Biol. Chem., 282, 16713–16717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Prada I., Amin L., Furlan R., Legname G., Verderio C., Cojoc D. (2016) A new approach to follow a single extracellular vesicle-cell interaction using optical tweezers. BioTechniques, 60, 35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]