Abstract

Cell Division Cycle 6 (Cdc6) is a component of pre-replicative complex (preRC) forming on DNA replication origins in eukaryotes. Recessive mutations in ORC1, ORC4, ORC6, CDT1 or CDC6 of the preRC in human cause Meier-Gorlin syndrome (MGS) that is characterized by impaired post-natal growth, short stature and microcephaly. However, vertebrate models of MGS have not been reported. Through N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea mutagenesis and Cas9 knockout, we generate several cdc6 mutant lines in zebrafish. Loss-of-function mutations of cdc6, as manifested by cdc6tsu4305 and cdc6tsu7cd mutants, lead to embryonic lethality due to cell cycle arrest at the S phase and extensive apoptosis. Embryos homozygous for a cdc6 hypomorphic mutation, cdc6tsu21cd, develop normally during embryogenesis. Later on, compared with their wild-type (WT) siblings, cdc6tsu21cd mutant fish show growth retardation, and their body weight and length in adulthood are greatly reduced, which resemble human MGS. Surprisingly, cdc6tsu21cd mutant fish become males with a short life and fail to mate with WT females, suggesting defective reproduction. Overexpression of Cdc6 mutant forms, which mimic human CDC6(T323R) mutation found in a MGS patient, in zebrafish cdc6tsu4305 mutant embryos partially represses cell death phenotype, suggesting that the human CDC6(T323R) mutation is a hypomorph. cdc6tsu21cd mutant fish will be useful to detect more tissue defects and develop medical treatment strategies for MGS patients.

Introduction

During DNA replication in eukaryotes, multiple replication origins are first recognized and bound during early G1 phase of the cell cycle by the origin recognition complex (ORC) consisting of ORC1-6 (1,2). Then, Cdc6, Cdt1 and the MCM2-7 helicase complex are sequentially recruited to each ORC-bound origin to form a pre-replicative complex (preRC) so that the origin is licensed for DNA replication. During the S phase, other factors are recruited to the preRCs to initiate DNA synthesis. It has been found that recessive mutations in ORC1, ORC4, ORC6, CDT1 or CDC6 of the preRC in human cause Meier-Gorlin syndrome (MGS) (3), also called ear patella short stature syndrome, which is characterized by impaired pre- and post-natal growth, short stature, microcephaly, microtia and absent or small patellae (2,4). A significant proportion of MGS patients also have abnormalities of genital and secondary sexual development (4). It remains unknown whether the reproduction and longevity of MGS patients are affected (2,4).

Cdc6 belongs to the AAA+ ATPase family and is essential for preRC formation by helping MCM proteins load onto replication origins. Cdc6 can also activate Cdk2 to promote S phase progression and G1 to S phase transition (5,6). In addition, Cdc6 has been found to inhibit apoptosome assembly and cell death by forming stable complexes with activated Apaf-1 molecules (7), to participate in spindle formation (8–10), and to regulate transcription of several cancer-related genes (11) and ribosomal DNA (12). Up-regulated expression of CDC6 has been found to associate with the malignant progression of various tumors, and so CDC6 is a candidate prognostic marker and therapeutic target of several types of cancers (13–18). In the zebrafish, co-overexpression of cdc6 and c-myc in skin stimulates tumor-like transformation and genome instability (19). One MGS patient has been found to be homozygous for the missense mutation 968 C > G in the CDC6 coding region, leading to the T323R substitution in the ATPase domain (3). The unavailability of animal models of CDC6 mutation-caused MGS makes it difficult to investigate underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms. In addition, it remains unknown whether Cdc6 is essential for embryonic development in vertebrates.

In this study, we report several zebrafish mutant lines that carry different mutations in the cdc6 gene. Both cdc6tsu4305, which harbors a point mutation induced by N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) mutagenesis, and cdc6tsu7cd, which carries a 7-bp deletion with frameshift generated by Cas9 knockout, are null alleles and zygotic homozygous mutants are embryonic lethal. In contrast, cdc6tsu21cd has a 21-bp deletion in frame and homozygous mutant fish are smaller with infertility and a short life, which resemble human MGS. The cdc6tsu21cd mutant can be used as an animal model of MGS to identify tissue and organ defects in detail and develop medical treatment strategies for MGS patients.

Results

tsu4305 mutants are embryonic lethal and carry a point mutation in the cdc6 locus

During an ENU-mediated mutagenesis screen, we identified the tsu4305 line. Around 22-h post-fertilization (hpf), a proportion of embryos derived from crosses between heterozygotes looked darker in the head due to extensive cell death (Fig. 1A). These embryos thereafter exhibited increasing degenerative tissues with a curved trunk (Fig. 1A) and eventually died around 2–3 days post-fertilization (dpf). Abnormal embryos usually accounted for about 25% among siblings (see an example in Fig. 1B), which fits the Mendelian Law of Segregation. Thus, those abnormal embryos are zygotic mutants that are homozygous at a single mutant locus.

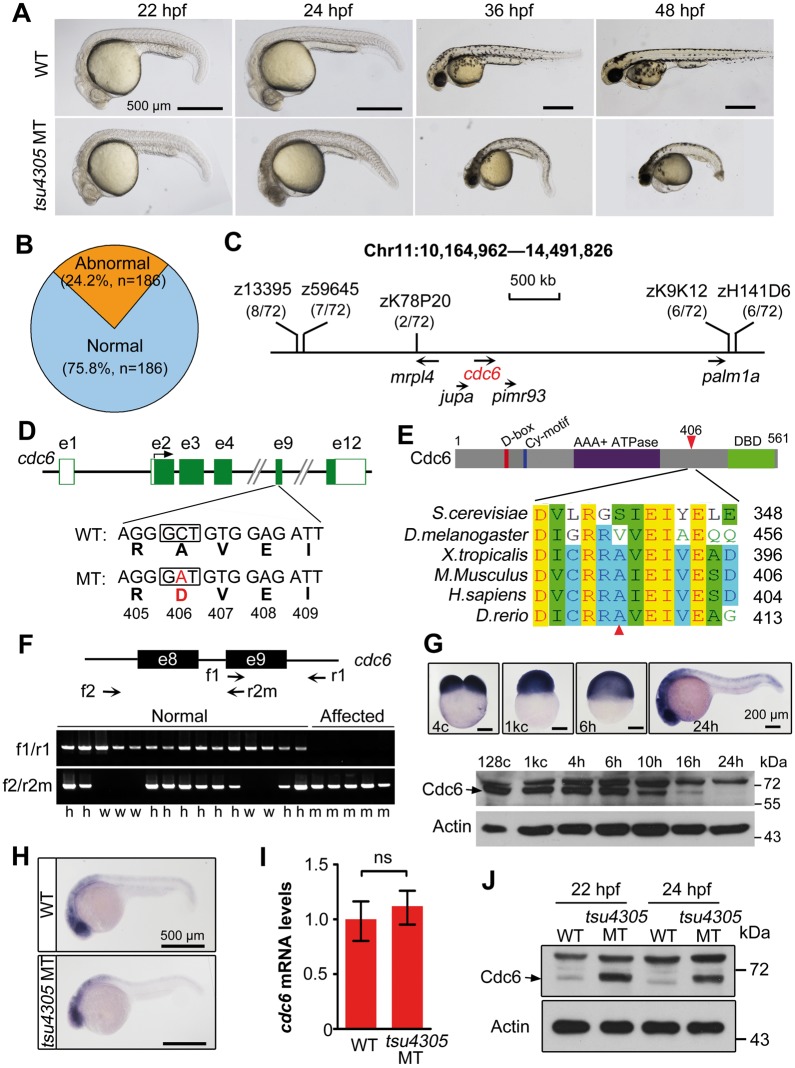

Figure 1.

tsu4305 mutants are embryonic lethal due to a mutation of the cdc6 locus. (A) Morphology of mutants at indicated stages compared with WT siblings. (B) Percentage of mutant embryos at 24 hpf derived from a single family. n, total number of embryos. (C) The mutant gene is mapped to a region on chromosome 11. Polymorphic markers were shown with the recombinant rate in parentheses and candidate genes were indicated. (D) The point mutation in the 9th exon of the cdc6 locus results in a substitution of A406D in Cdc6 protein. (E) Alignment of amino acid sequences in a region surrounding A406 of Cdc6. The structure of zebrafish Cdc6 was illustrated on the top. The substituted residue was indicated by arrowheads. (F) Genotyping of embryos in a mutant family. Embryos derived from a single pair of tsu4305 heterozygous fish were morphologically divided at 24 hp into normal and affected groups and genotyped using two pairs of specific primers (indicated on the top). h, w and m represent heterozygous, WT and mutant genotypes, respectively. (G) Expression of Cdc6 in WT embryos. cdc6 mRNA distribution was detected by in situ hybridization (top panel) and protein levels were examined by Western blotting (bottom panel) at indicated stages. cdc6 mRNA level in mutants is comparable to that in WT siblings as examined at 24 hpf by in situ (H) and RT-PCR (I). ns, statistically non-significant (P > 95%). (J) Cdc6 protein level is increased in mutants compared with WT siblings at indicated stages.

To identify the gene responsible for tsu4305 mutant phenotype, we performed positional cloning assay as described previously (20). Genetic mapping located the mutation site to a 3-Mb region harboring mrpl4, jupa, cdc6, pimr93 and palm1a loci on chromosome 11 (Fig. 1C). Sequencing of coding regions of these genes identified a C > A point mutation in the ninth exon of cdc6. This nucleotide substitution would result in replacement of the nonpolar residue alanine by the negatively charged residue aspartic acid at position 406 of Cdc6 protein (Fig. 1D), which is defined as A406D. Zebrafish Cdc6 shares 60.7% homology of amino acid sequence with human CDC6, and in particular, known D-box, Cy-motif, AAA+ ATPase domain and winged helix-turn-helix DNA-binding domain (DBD) are highly conserved. However, the A406-containing region of Cdc6 is conserved across vertebrate species (Fig. 1E) with no defined function. The A406D substitution in tsu4305 mutants may change the properties and thus functions of Cdc6 protein.

PCR analysis of the cdc6 mutant region with two pairs of specific primers revealed that all abnormal embryos were homozygous for the mutant allele while normal embryos were either homozygous for the wild-type (WT) allele or heterozygous for WT and mutant alleles (exemplified in Fig. 1F), suggesting that cdc6 is the causative mutant gene. Whole-mount in situ hybridization showed that cdc6 transcripts were abundant with ubiquitous distribution from fertilization through gastrulation, and persisted at high levels in the central nervous system (CNS) at 24 hpf (Fig. 1G, upper panel). High levels of cdc6 expression in the CNS, a tissue with vigorous cell proliferation, may explain why cell death in cdc6tsu4305 mutant embryos happens first in the head at 22 hpf and became more prominent in the CNS than other tissues at 24 hpf (Fig. 1A). Cdc6 protein level was high before and at the gastrulation onset (6 hpf) and then declined (Fig. 1G, lower panel). In tsu4305 mutants, the cdc6 mRNA level appeared comparable to WT siblings (Fig. 1H and I). However, Cdc6 protein level in mutants was much higher than in WT siblings (Fig. 1J). Given that Cdc6 protein level fluctuates during cell cycle (21,22), higher levels of mutant Cdc6 protein suggest that many embryonic cells in mutant embryos are arrested at the phases during which Cdc6 normally accumulates, or that Cdc6(A406D) mutant protein is more stable.

tsu4305-encoded Cdc6(A406D) protein is non-functional

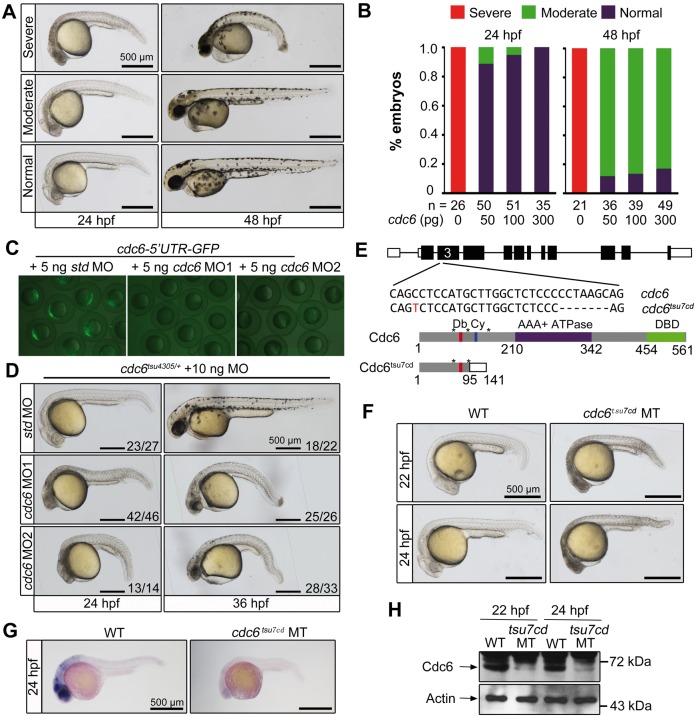

To investigate whether the tsu4305 phenotype is caused by loss or gain of function of Cdc6, we first performed rescue experiments. Over 90% of mutant embryos injected at one-cell stage with WT cdc6 mRNA did not show degenerative CNS at 24 hpf and had a straight trunk with death of some cells in the head at 48 hpf (Fig. 2A and B), suggesting a temporary rescue effect. In contrast, injection of tsu4305 mutant mRNA in WT or mutant embryos had no effect (data not shown). Next, we designed two antisense morpholinos to block expression of cdc6 mRNA in WT embryos (Fig. 2C). WT embryos injected with 20 ng of either MO phenocopied tsu4305 mutants (data not shown); however, tsu4305 heterozygous embryos injected with 10 ng of either MO showed similar phenotype (Fig. 2D). These results suggest that tsu4305 is most likely a null allele. Finally, we generated cdc6 mutants using CRISPR/Cas9 technology to target the third exon of the cdc6 locus. Consequently, we identified two mutant lines, cdc6tsu7cd (Fig. 2E) and cdc6tsu21cd (described later), which carried 7- and 21-bp deletion within the coding region, respectively. In cdc6tsu7cd, the mutant allele would encode the first 95 residues of Cdc6 protein, which is followed by 46 residues that are not present in Cdc6 protein due to the frame shift. Embryos homozygous for cdc6tsu7cd displayed a phenotype almost identical to that of tsu4305 mutant embryos (Fig. 2F). In cdc6tsu7cd mutants at 24 hpf, cdc6 mRNA was not detectable (Fig. 2G) and Cdc6 protein was drastically reduced (Fig. 2H), suggesting that aberrant mRNA is rapidly degraded. Thus, the cdc6tsu7cd phenotype is due to loss of zygotic cdc6 mRNA and protein. The shared phenotype between tsu4305 and cdc6tsu7cd mutants strongly indicates that the tsu4305 phenotype is ascribed to loss of function of zygotically synthesized Cdc6(A406D).

Figure 2.

cdc6 morphants and knockout mutants phenocopy tsu4305 mutants. Rescue effect of cdc6 mRNA overexpression in tsu4305 mutants. One-cell stage embryos derived from tsu4305 heterozygote crosses were injected with different doses of cdc6 mRNA and then individually photographed followed by genotyping at 24 or 48 hpf. Only embryos homozygous for tsu4305 were chosen for categorizing into three types. (A) Morphology of injected tsu4305 mutant embryos in different categories. (B) Percentage of embryos in each category. (C) Effectiveness of cdc6 MOs. WT embryos at the one-cell stage were injected with 60 pg of the reporter pcdc6-5′UTR-GFP DNA in combination with different MOs and fluorescence was examined by microscopy at the shield stage. std MO, standard control MO. (D) Morphology of cdc6tsu4305 heterozygous embryos injected with 10 ng of corresponding MO. The ratio of embryos with representative morphology was indicated. (E) Knockout of cdc6 by Cas9 technology. The cdc6tsu7cd allele was identified after targeting the 3rd exon of the cdc6 locus (top panel), which carried a 7-bp deletion so that a premature stop codon was introduced. The predicted mutant protein is truncated (bottom panel). Db, D-box; Cy, Cy-motif; DBD, DNA-binding domain; *, serine phosphorylation sites. (F) Morphology of cdc6tsu7cd homozygous mutants. WT, wild-type; MT, mutant. cdc6 mRNA (G) and protein levels (H) in cdc6tsu7cd mutants, which were examined at indicated stages by in situ hybridization and Western blotting. Note that lower amount of Cdc6 protein in mutants could be maternally supplied protein or translated from maternal cdc6 mRNA.

Embryonic cells in tsu4305 are arrested at the S phase and undergo apoptosis

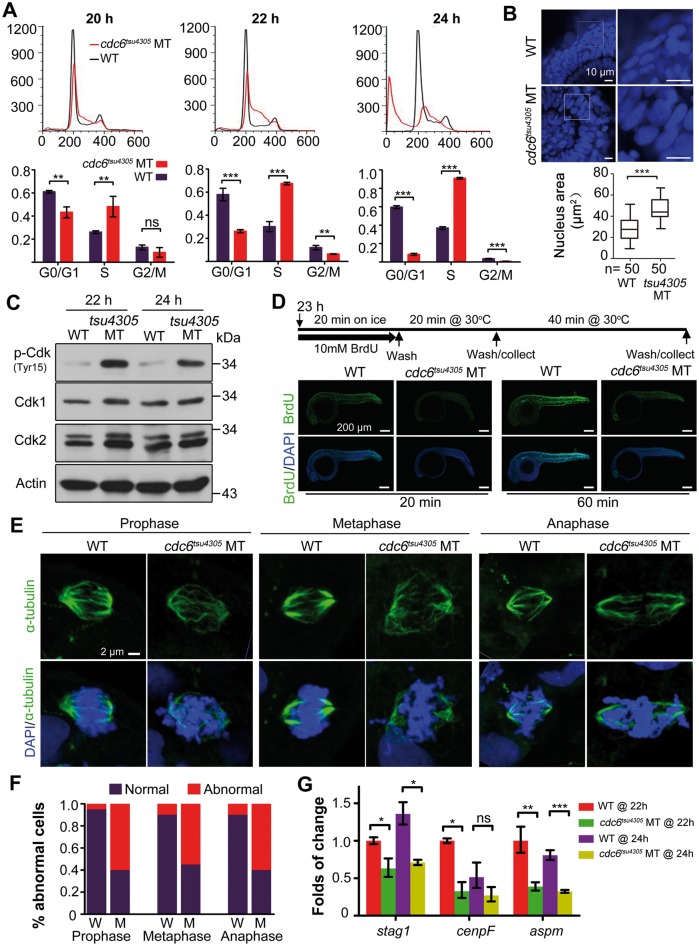

Given that Cdc6 is required for DNA replication in yeast and mammalian cells, we asked whether DNA replication in embryonic cells of zygotic tsu4305 mutant embryos is affected. To address this issue, we performed FACS-based cell cycle analysis using embryos at different stages, which were derived from crosses between tsu4305 heterozygous fish. Embryos at 20 hpf, at which there was no visible phenotype in mutants, were individually lysed and genotyped. We found that, compared with WT siblings, mutant embryos had more cells stopped at the S phase with less cells at the G0/G1 phase (Fig. 3A). At 22 and 24 hpf when massive apoptotic cells in mutants appeared, many more cells in mutant embryos were arrested at the S phase with a decreased proportion of cells at the G0/G1 and G2/M phases (Fig. 3A). Consistent with the S-phase arrest, larger nuclei were observed in mutants (Fig. 3B). Cdk1 and Cdk2 can be activated by dephosphorylation at Tyr15, which promotes the S phase (23,24). We found that levels of Cdk phospho-Tyr15 were increased markedly in mutant embryos (Fig. 3C), which are consistent with the increased levels of Cdc6 (Fig. 1J). Furthermore, BrdU incorporation assay showed that much less amount of BrdU was incorporated into DNA in mutants (Fig. 3D), which supports the idea that the cell cycle is arrested.

Figure 3.

Mitotic defects in cdc6tsu4305 mutants. (A) DNA content analysis by flow cytometry. Embryos at 20 hpf were individually genotyped prior to flow cytometry and then grouped accordingly. Embryos at 22 and 24 hpf were identified by morphology. The percentages of cells at different phases were shown in lower panel based on three independent experiments. WT, homozygous WT genotype at 20 hpf or morphological WT at 22 and 24 hpf; MT, cdc6tsu4305 mutants. Statistical significance levels: **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, non-significant (P > 95%). (B) Morphology of nuclei of retinal epithelia at 24 hpf. Nuclei were visualized by DAPI staining and observed by confocal microscopy (top panel). The average area of nuclei was calculated based on 50 cells (n) using Image J software. (C) phospho-Cdk1/2 levels are increased in cdc6tsu4305 mutants (MT) at 24 hpf. The relevant proteins levels were examined by Western blotting. (D) Cell proliferation in cdc6tsu4305 mutants is impaired as revealed by BrdUTP incorporation. Top panel illustrated processes of embryo treatments in BrdUTP. Bottom panel showed immunofluorescence results following immunostaining of treated embryos with anti-BrdUTP antibody (green) and DAPI (blue). Abnormal segregation of chromosomes in cdc6tsu4305 mutants. Mitotic spindles were labeled by anti-α-tubulin antibody immunostaining (green) and chromosomes were stained by DAPI (blue). The showed mitotic cells (E) were chosen from the spinal cord at 24 hpf for confocal microscopy. The percentage of cells undergoing abnormal mitosis was shown in (F). W, wild-type embryos; M, mutant embryos. The total number of observed mitotic cells was 20 for each group. (G) Expression of three genes related to spindle function and chromosomal segregation is up-regulated in cdc6tsu4305 mutants at 22 and 24 hpf as analyzed by RT-PCR. Statistical significance levels (three independent experiments): *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns, non-significant (P > 95%).

We wondered whether the S-phase arrest of tsu4305 mutant cells is accompanied by abnormal segregation of chromosomes. To address this question, we examined spindle formation and chromosome segregation in tsu4305 mutants by immunofluorescence with anti-α-tubulin antibody for spindles and DAPI for chromosomes. Results showed that tsu4305 mutants at 24 hpf had a much higher proportion of abnormal mitotic cells with disordered chromosomal arrangement at various phases (Fig. 3E). Interestingly, three genes, stag1, cenpF and aspm, which are involved in spindles formation and chromosomes segregation, were down-regulated in tsu4305 mutants (Fig. 3F). These results indicate that incomplete DNA replication due to deficiency of zygotic functional Cdc6 is associated with abnormal segregation of chromosomes.

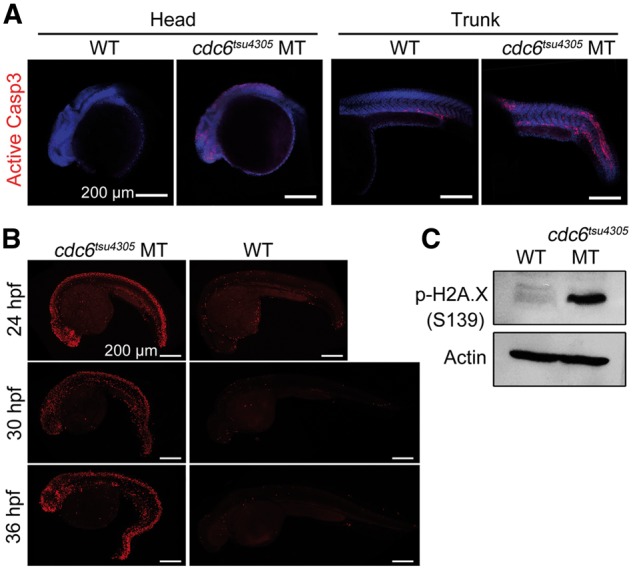

Considering that Cdc6 also plays a role in prevention of apoptosis by blocking apoptosome assembly (7), we guess that cell death in tsu4305 occurs through apoptosis. Immunostaining with anti-active Caspase3 antibody indeed detected much more active Caspase3 in tsu4305 mutants at 24 hpf (Fig. 4A). TUNEL assay result showed massive DNA fragmentation in tsu4305 mutants, mainly in the CNS (Fig. 4B). The level of H2A.X phosphorylated at S139, a marker for DNA double-strand breaks (25), was drastically increased in tsu4305 mutants (Fig. 4C). These observations indicate that Cdc6 insufficiency in tsu4305 mutants, which results from gradual loss of functional maternal Cdc6 protein and no supply of functional zygotic Cdc6 protein, eventually induces apoptosis.

Figure 4.

cdc6tsu4305 mutant embryos undergo excess apoptosis. (A) Detection of active Caspase3. Embryos at 24 hpf were subjected to immunostaining with anti-active Caspase3 antibody and staining with DAPI and observed by confocal microscopy. (B) Detection of DNA fragmentation by TUNEL assay. All embryos were positioned with anterior to the left. (C) Detection of p-H2A.X in 24-hpf embryos by Western blotting. WT, wild-type siblings; MT, cdc6tsu4305 mutants.

cdc6tsu4305 mutant embryos can be used to in vivo verify functional domains of Cdc6

Since tsu4305 mutant embryos can be rescued provisionally by overexpression of WT cdc6 mRNA (Fig. 2A and B), they would be useful for verifying known or unknown functional domains of Cdc6. Then, we made deletional or mutational forms of cdc6 (Fig. 5A) and tested their activity by overexpression in tsu4305 mutants.

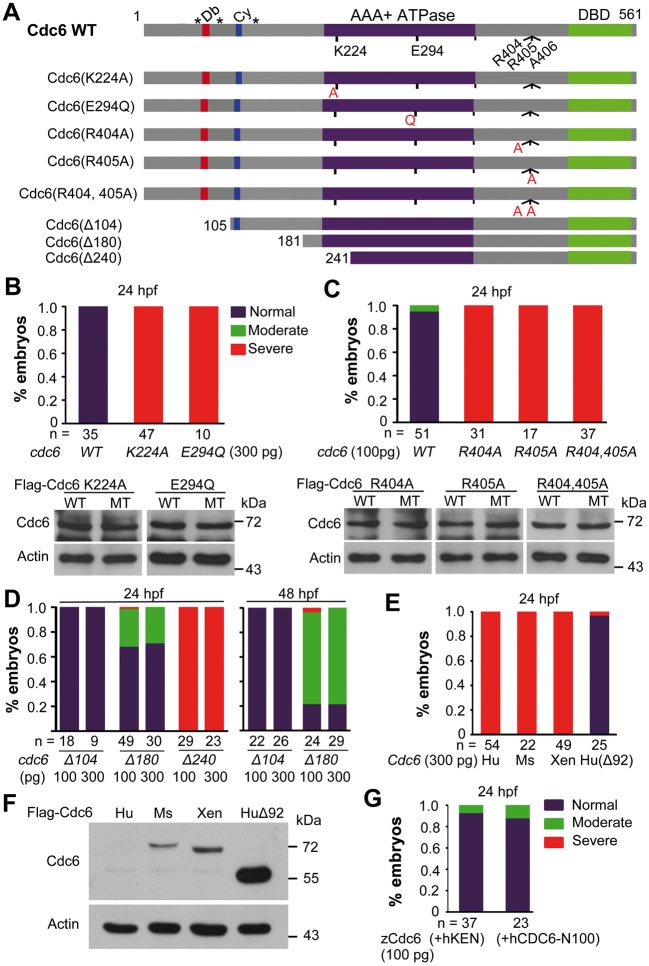

Figure 5.

Rescue effects of overexpression of different cdc6 forms in cdc6tsu4305 mutant embryos. (A) Illustration of various mutant forms of zebrafish cdc6. Db, D-box; Cy, Cy-motif; DBD, DNA-binding domain; *, serine phosphorylation sites. (B–E) Percentages of embryos in different categories. One-cell stage embryos derived from cdc6tsu4305 heterozygous fish crosses were injected with individual mRNA species at indicated doses and photographed individually at 24 hpf and genotyped. Only those with mutant genotype were counted. Categorization of mutant embryos was similar to Figure 2A (left panel). In some cases, protein translated from injected mRNA in embryos was examined by Western blotting (B, C). In (E), Cdc6 genes of other species were used: Hu, human; Ms, mouse; Xen, Xenopus; Hu(Δ92), human CDC6 with the deletion of the first 92 residues. (F) Cdc6 protein levels after mRNA injection. WT embryos at the one-cell stage were injected with 100 pg of mRNA encoding Flag-tagged human (Hu), mouse (Ms), or Xenopus (Xen) Cdc6 and examined at the bud stage for protein levels by Western blot. Actin level was also examined in parallel as a control. (G) Rescue effect of two modified zebrafish Cdc6. 100 pg of zCdc6(+hKEN) or zCdc6(+hCDC6-N100) mRNA was injected into one-cell stage embryos derived from cdc6tsu4305 heterozygous fish crosses and the embryos were observed/categorized at 24 hpf followed by genotyping.

The Walker A and the Walker B motifs in the AAA+ ATPase domain of Cdc6 protein are essential for loading MCM complexes onto replication origins (26,27). We made two zebrafish cdc6 mutant mRNAs, cdc6(K224A) and cdc6(E294Q), which lead to K224A substitution in the Walker A motif and E294Q substitution in the Walker B motif respectively (Fig. 5A). Unlike WT cdc6 mRNA injection, injection of either cdc6(K224A) or cdc6(E294Q) mRNA into tsu4305 mutant embryos failed to prevent cell death as observed at 24 hpf (Fig. 5B), confirming the importance of the ATPase domain.

Zebrafish Cdc6 has two consecutive arginine residues immediately N-terminal to A406 that is mutated to 406D in tsu4305 mutants. These two arginine residues are conserved from fly to human and the second arginine residue is replaced by the polar amino acid glycine in yeast (Fig. 2E). We made the mutant forms Cdc6(R404A), Cdc6(R405A) and Cdc6(R404, 405A), which changed arginine to the nonpolar residue alanine at the corresponding positions. Overexpression of mRNAs encoding these mutant forms of Cdc6 in tsu4305 mutant embryos was totally unable to inhibit cell death at 24 hpf (Fig. 5C). We therefore believe that R404 and R405 located outside the ATPase domain are absolutely required for normal function of Cdc6.

In the N-terminal region of Cdc6, the D-box is required for ubiquitination and degradation (28), and cyclin-binding (Cy) motif and several Cdk phosphorylation sites are implicated in interaction with Cdks and cytoplasmic translocation (29). We found that overexpression of cdc6(Δ104), which lacks the D-box, could rescue tsu4305 mutants as efficiently as did WT cdc6 (Fig. 5D), suggesting that Cdc6(Δ104) is functional in embryos. When compared with cdc6(Δ104), rescue effect of cdc6(Δ180), which deleted the D-box, Cy-motif and all known N-terminal phosphorylation sites, was slightly reduced, implying that interaction with Cdks is required for full activity of Cdc6. Like cdc6(K224A) (Fig. 5B), cdc6(Δ240) that deletes all of the N-terminal motifs as well as a part (including the Walker A motif) of the ATPase domain, completely lost the rescue activity in tsu4305 mutants (Fig. 5D). Generally, these data are in agreement with the previous findings on functions of Cdc6 N-terminal domains.

Next, we investigated functional conservation of Cdc6 from different vertebrate species. To our surprise, we observed that injection of human, mouse or Xenopus full-length Cdc6 mRNA into tsu4305 mutant embryos was unable to alleviate cell death (Fig. 5E). Interestingly, overexpression of human CDC6(Δ92), which deleted the first 92 residues at the N-terminus including the D- and KEN- boxes and would lead to more stability of the protein (28,30), effectively blocked cell death in tsu4305 mutants. Western blotting result indeed showed that injection of human CDC6 mRNA into WT embryos produced undetectable level of the protein product while injection of CDC6(Δ92) mRNA gave rise to massive protein product; mouse or Xenopus Cdc6 mRNA injection resulted in protein product at levels much lower than that from CDC6(Δ92) mRNA injection (Fig. 5F). We then made the construct zCdc6(+hKEN) by inserting a KEN box containing peptide (GKKENGPPH) derived from human CDC6 into zebrafish Cdc6 and the construct zCdc6(+hCDC6-N100) by replacing the N-terminal 113-residue portion of zebrafish Cdc6 with the N-terminal 100-residue fragment of human CDC6. Overexpression of either construct effectively rescued tsu4305 mutants (Fig. 5G), implying that the KEN box and other motifs in the N-terminal part of human CDC6 may not be responsible for protein instability in zebrafish embryos. It is likely that the molecular mechanisms regulating Cdc6 function in embryos may differ among species.

cdc6tsu21cd mutant fish become males with a smaller size and a shorter life

The mutant line cdc6tsu21cd, generated by Cas9 gene targeting, carries a 21-bp deletion in frame in the third exon of the cdc6 locus. The resulted mRNA is expected to produce a protein with deletion of seven residues (K97QRCAPL103) in between the D-box and Cy-motif and the C104L substitution immediately adjacent to the Cy motif (Fig. 6A). The importance of this deleted region is not yet known. The cdc6tsu21cd mutant embryos grew normally and did not exhibit morphological defects before 15 dpf. However, at 30 dpf, mutant fish were smaller with a significantly reduced body length compared with their WT or heterozygous siblings (Fig. 6B). As measured at 100 dpf when fish are in young adulthood, the average body weight and length of mutant fish were only 36.6 and 69.6% of the WT siblings (Fig. 6C), respectively. The body weight and length of heterozygous fish at 100 dpf were 88.7 and 99.6% of the WT siblings, respectively, which were not statistically significant. Apparently, the growth of cdc6tsu21cd mutant fish is retarded, which resembles short stature characteristic of human MGS (2,4).

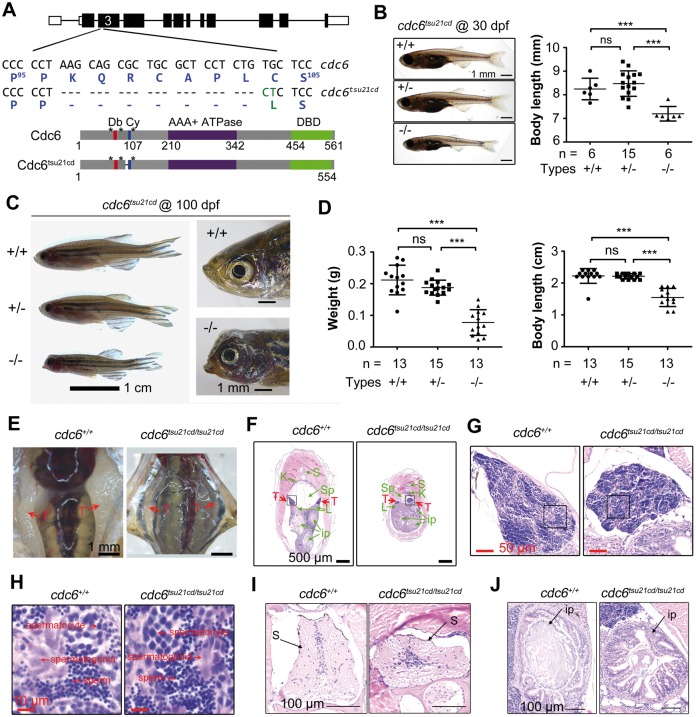

Figure 6.

Growth retardation and abnormal tissues of cdc6tsu21cd mutants. (A) Illustration of cdc6tsu21cd mutant allele and protein. The deleted nucleotides and residues were represented by dashes and substitutions were labeled in green letters. Db, D-box; Cy, Cy-motif; DBD, DNA-binding domain. (B) Morphology (left) and body length (right) of larva at 30 dpf. Larva derived from cdc6tsu21cd heterozygous fish matings were genotyped using tail fin DNA. Morphology (C), weight and body length (D) of fish at 100 dpf. Embryos derived from cdc6tsu21cd heterozygous fish matings were raised to 30 dpf when genotyping was performed using tail fin DNA and then continued growing to 100 dpf. n, number of measured larva or adults. Statistical significance levels: ***P < 0.001; ns, non-significant (P > 95%). (E) Visualization of testes in adult fish. (F) Cross section of adult fish after hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. Testes (T) were indicated by red arrows. Green arrow-indicated tissues were: S, spine; K, kidney; Sp, swimming bladder; L, liver; ip, intestinal loops. (G) The testes boxed in (F) were observed at high power. (H) Testis areas boxed in (G) were observed at high power. (I) Enlarged spine (S) shown in (F). (J) Enlarged intestinal loop shown in the upper right in (F).

We extended our observation to mating behavior and longevity of cdc6tsu21cd mutant adults. Most of the mutant fish looked slim, a typical feature of males, and the other had a slightly floated belly, an indication of potential females. When 12 young cdc6tsu21cd mutant adults aging from 3- to 5-months old were individually mated to WT males or females, however, none of the mating pairs laid eggs, suggesting a failure of reproduction. It was observed that, when placed together with a WT male or female, the mutant fish did not move much and always tried to escape from the WT fish’s approach. Then, 5 mutant fish were anatomically analyzed. Surprisingly, all of the analyzed mutant fish had smaller testes with sperms (Fig. 6E–H), indicating that they were males. It is believed that zebrafish larvae at 10–14 dpf all form a pair of juvenile ovaries as the default fate of gonad primordia; and these juvenile ovaries will be transformed into testes if exposed to a stress such as less food, insufficient oxygen and inappropriate temperature (31). Therefore, we hypothesize that the cdc6tsu21cd mutant larvae are most likely to become males because of poor health condition. But, it remains elusive why the mutant males fail to mate with WT female.

We raised cdc6tsu21cd mutant fish, heterozygous and WT siblings separately but in the same conditions after genotyped at one month old, which could avoid competition. Observation of two batches of siblings indicated that none of cdc6tsu21cd mutant fish was alive beyond 8 months, while WT and heterozygous siblings were still alive after 14 months (to now) (Table 1). The zebrafish normally has an average life span of 36–42 months depending on strains (32). Apparently, cdc6tsu21cd mutant fish are short-lived. We observed that the cdc6tsu21cd mutant fish had an abnormal head with misshapen mouth (Fig. 6C), swam slowly and did not eat food actively (Supplementary Material, Movie S1). In fact, the cdc6tsu21cd mutant adults showed many abnormal tissues including the spine, swimming bladder, intestine, livers and so on (Fig. 6F, I and J). In general, these defects all might cause health problems and ultimately lead to a shorter life. The major causes of the reduced lifespan of the mutant fish need to be investigated in depth in the future.

Table 1.

Survival rate of cdc6tsu21cd mutantsa

| Batches | Age (months) | Number of fish (survival rateb) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| +/+ | +/− | −/− | ||

| 1 | 1 | 6 | 15 | 6 |

| 3 | 6 (100%) | 14 (93.3%) | 6 (100%) | |

| 5 | 6 (100%) | 14 (93.3%) | 4 (66.7%) | |

| 7 | 6 (100%) | 14 (93.3%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 2 | 1 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| 3 | 13 (86.7%) | 15 (100%) | 13 (86.7%) | |

| 5 | 13 (86.7%) | 15 (100%) | 9 (60%) | |

| 7 | 13 (86.7%) | 14 (93.3%) | 1 (6.7%) | |

| 8 | 13 (86.7%)c | 14 (93.3%)c | 0 (0%) | |

Embryos derived from a single cdc6tsu21cd heterozygous fish cross were raised to 30 dpf and then genotyped using tail fin DNA. The genotyped fish continued growing up.

The survival rate was calculated based on the number of fish at 1-month old.

These WT and heterozygous fish are still alive up to now (over 14 months).

Zebrafish cdc6tsu21cd and human CDC6(968C > G)(T323R) are hypomorphic alleles

In comparison with cdc6tsu4305 and cdc6tsu7cd mutants that are embryonic lethal, cdc6tsu21cd mutants are normal during embryonic and larval stages, suggesting that cdc6tsu21cd-encoded protein retains certain functional activity. To test this possibility, we injected synthetic cdc6tsu21cd mRNA (Fig. 7A) into one-cell stage cdc6tsu4305 embryos and observed morphology and performed TUNEL assay at 24 hpf, which were followed by genotyping. Results showed efficient prevention of cell death in cdc6tsu4305 mutant embryos injected with cdc6tsu21cd mRNA (Fig. 7A and B), suggesting that cdc6tsu21cd-encoded protein has considerably high levels of functional activity.

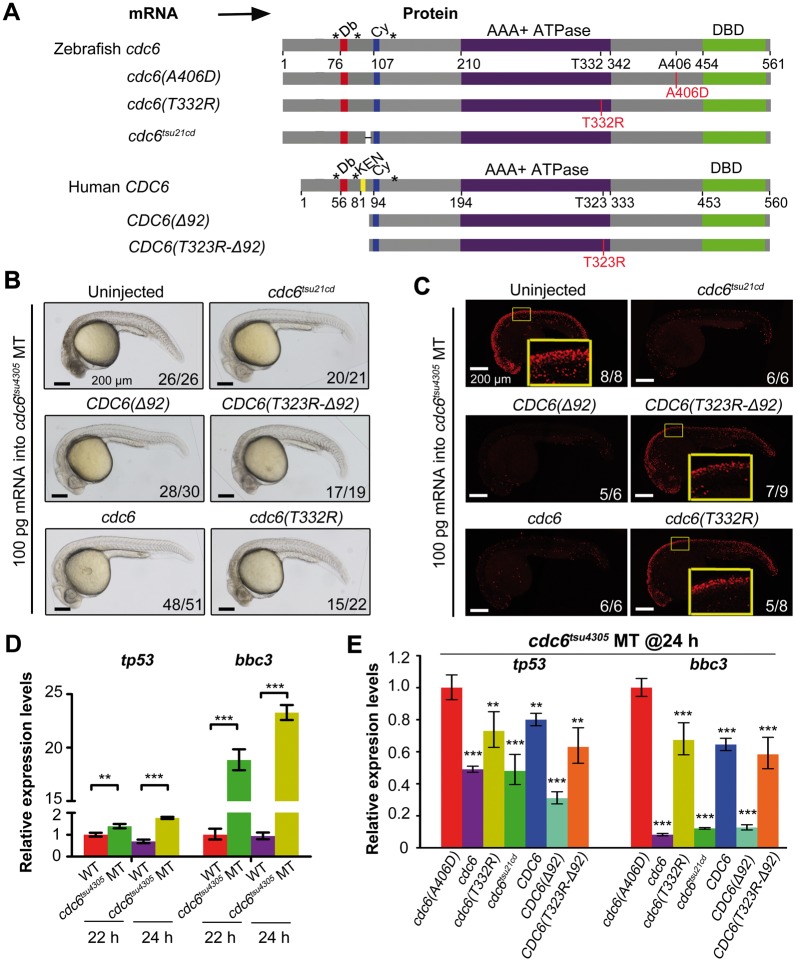

Figure 7.

Functional assay of zebrafish cdc6tsu21cd and human CDC6(T323R) alleles in zebrafish cdc6tsu4305 mutant embryos. (A) Illustration of zebrafish and human mutant forms of Cdc6. The D-box, KEN-box, Cy-motif, ATPase domain, DBD, phosphorylatable serines (*) were indicated. Morphology (B) and TUNEL assay results (C) of cdc6tsu4305 mutant embryos at 24 hpf. Embryos derived from heterozygous fish crosses were injected with indicated mRNA at the one-cell stage, and analyzed at 24 hpf, which was followed by genotyping of individuals. The ratio of embryos with representative morphology or signals was shown in the right corner of each picture. In (C), the boxed areas of several TUNEL confocal pictures were enlarged for easier comparison. (D) Up-regulated expression of tp53 and bbc3 in cdc6tsu4305 mutants at 22 and 24 hpf as analyzed by RT-PCR. WT, wild-type siblings; MT, mutants. (E) Relative expression levels of tp53 and bbc3 in cdc6tsu4305 mutants at 24 hpf. Embryos injected with indicated mRNA (100 pg per embryo) were individually lysed at 24 hpf. After genotyping using an aliquot of cells, the remaining cells of embryos homozygous for cdc6tsu4305 allele were mixed and the isolated RNA was used for RT-PCR. In (D, E), statistical significance levels are: **, P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

A human CDC6 (968C > G) homozygous patient develops MGS (3). This mutation is expected to encode CDC6(T323R) mutant protein. As shown above, overexpression of human WT CDC6 mRNA failed to rescue cdc6tsu4305 mutant embryos, but, overexpression of human CDC6(Δ92) mRNA coding for N-terminal truncated form had a good rescue effect (Fig. 5E). Then, we made human CDC6(T323R-Δ92) mRNA (Fig. 7A) to perform rescue experiments. As shown in Figure 7B and C, cell death in injected cdc6tsu4305 mutants was not as severe as in uninjected mutants, and the number of apoptotic cells in the head and spinal cord of injected mutants appeared slightly reduced. The threonine residue at position 323 of human CDC6 has the counterpart at position 332 of zebrafish Cdc6. So, we made zebrafish cdc6(T332R) mRNA to do rescue experiments and found a weak rescue effect in cdc6tsu4305 mutants (Fig. 7B and C), which was similar to injection of human CDC6(T323R-Δ92) mRNA. These results imply that T323R substitution of human CDC6 may lead to partial loss of function.

We noted that the expression of the apoptosis-related genes tp53 and bbc3 was highly up-regulated in cdc6tsu4305 mutants (Fig. 7D) so that they could be used as markers to quantitatively verify the rescue effect. Overexpression of cdc6(A406D) in cdc6tsu4305 mutants had no effect on tp53 and bbc3 expression and so this injection was used as control. When compared with cdc6(A406D) injection, zebrafish cdc6 or cdc6tsu21cd or human CDC6(Δ92) mRNA injection significantly repressed tp53 and bbc3 expression in cdc6tsu4305 mutants at 24 hpf, and zebrafish cdc6(T332R) or human CDC6 or CDC6(T323R-Δ92) mRNA injection also compromised upregulation of tp53 and bbc3 expression in cdc6tsu4305 mutants though to a lesser extent. Therefore, we believe that both zebrafish cdc6tsu21cd and human CDC6(T323R) are hypomorphic mutant alleles. This explains why the human patient carrying homozygous CDC6(T323R) mutation was alive after birth.

Discussion

A human patient with MGS has been found to be homozygous for CDC6(T323R) mutation. However, genetic mutants of Cdc6 in vertebrates have not been generated. By forward and reverse genetic approaches, we generate two loss-of-function mutant lines for cdc6 in zebrafish, cdc6tsu4305 and cdc6tsu7cd. We show that zygotic deficiency of functional Cdc6 causes embryonic lethality due to cell cycle arrest and extensive apoptosis. In zebrafish, maternal cdc6 transcripts are present in mature oocytes. These maternal messages would be sufficient to allow normal development of embryos from fertilization through somitogenesis. When maternally supplied Cdc6 gets less and less, mitosis of embryonic cells is halted mostly at the S phase, which ultimately leads to death of cells. The lethality of embryos without Cdc6 makes it difficult to study Cdc6 implication in germ cell formation and oocyte maturation in zebrafish. It is possible to study functions of maternal Cdc6 through conditional knockout.

The cdc6tsu4305 line harbors a single nucleotide mutation in the coding region, which would produce the mutant protein Cdc6(A406D) (Fig. 1D). However, the alanine residue at 406 is conserved in Cdc6 homologues across vertebrate species, and is changed to the uncharged polar residue serine in yeast and the nonpolar residue valine in fly (Fig. 1E). We note that two consecutive positively charged arginine residues precede A406 in Cdc6. The A406D substitution in tsu4305 mutants may change the properties and thus functions of Cdc6 protein. As one piece of evidence, Cdc6 protein levels in mutant embryos are higher than in their WT siblings (Fig. 1J), suggesting that Cdc6(A406D) mutant protein is more stable though it is non-functional. In addition, overexpression of Cdc6(R404A) or Cdc6(R405A) fails to rescue cdc6tsu4305 mutant phenotype, indicating the importance of these residues for Cdc6 function. Based on the extrapolated 3-D structure of human CDC6 (33), RRA-containing region (R388KALDVCRRAIEIVE402), which is conserved in zebrafish Cdc6, forms the 13th α-helix, which is close to the Mg-ADP binding pocket. Therefore, we speculate that Cdc6(A406D) may lose ATPase activity.

Our mutant line cdc6tsu21cd carries a hypomorphic mutant allele that encodes a Cdc6 mutant protein with slightly reduced activity. cdc6tsu21cd fish show growth retardation and shorter body length, which are similar to human MGS caused by mutations of preRC complex components (2–4). We demonstrate that the CDC6(T323R) mutation leading to MGS could be hypomorphic as well (Fig. 7). The cdc6tsu21cd mutant fish have many abnormal tissues such as the spine and swimming bladder, but fins and pigmentation appear normal (Fig. 6B and C), which suggests that different tissues are disturbed differentially.

Given that cdc6tsu21cd fish develop MGS-like phenotype, this zebrafish mutant line could be used to further study how different tissues are affected and to develop medical treatment and care procedures for alleviating the defects.

Materials and Methods

Zebrafish strains, mutagenesis and mapping

Zebrafish Tuebingen (Tu) and India strains were used in this study with ethical approval from the Animal Care and Use Committee of Tsinghua University. Embryos were raised in Holtfreter’s solution at 28.5°C.

Chemical mutagenesis was performed as previously described (34,35). Briefly, WT Tu males aged 4–8 months were soaked into solution containing 3 mM ENU three times in one week and then crossed with WT India females to transmit induced mutations to next generation. Gene mapping was performed as previously described with modifications (20).

For Cas9-mediated gene targeting, gRNA target sequence (5′-GGAGCGCAGCGCTGCTTAGGGGG-3′) of zebrafish cdc6 was selected from the website (http://chopchop.cbu.uib.no/; data last accessed August 3, 2017). Synthetic Cas9 mRNA and gRNA were co-injected into Tu WT embryos at the one-cell stage. The founder fish (F0) and F1 fish carrying mutations were identified by digestion of T7 Endonuclease I that recognizes and cleaves non-perfectly matched DNA. Two mutant lines of cdc6, i.e. cdc6tsu7cd and cdc6tsu21cd were identified and maintained for analyses.

Genotyping

Two pairs of primers were used to identify WT cdc6 and cdc6tsu4305 mutant alleles by PCR. The sequences of primers were: 5′-CTGTATGTTACCAATAATGCTT-3′ (f1) and 5′-GTCAAAAAAAGGCAAAGAACTA-3′ (r1) for WT allele; 5′-CCAATAATGCTTACTATACAACTAC-3′ (f2) and 5′-TGCTTCCACAATCTCCACGT-3′ (r2) for cdc6tsu4305 mutant allele. In cases that mutant embryos were morphologically indistinguishable from WT embryos, cells of individual embryos were dissociated and a fraction of cells were used to extract DNA for genotyping; then, cells from embryos with an identical genotype were mixed for subsequent analysis. Or, individual embryos were first subjected to other analyses and then used for DNA extraction and genotyping.cdc6tsu21cdmutants were also identified by PCR using the following primers: the forward primer for WT allele: 5′-GCTTGGCTCTCCCCCTAAGCA-3′; the forward primer for mutant allele: 5′-GCTTGGCTCTCCCCCTCTCT-3′; and reverse primer for both alleles: 5′-AGGAAACAGTCGCGTAACAG-3′.

Constructs, morpholinos and microinjection

The full-length coding sequences of zebrafish cdc6 and human CDC6 were separately cloned into pCS2(+) vector with a Flag tag at N-terminal for in vitro synthesis of mRNAs. The mutant forms of zebrafish cdc6, including cdc6(A406D), cdc6(K224A), cdc6(E294Q), cdc6(R404A), cdc6(R405A), cdc6(R404,405A) and cdc6(T332R), were made by site-directed mutation on cdc6-containning vector. Three cdc6 truncated mutants, cdc6(Δ104), cdc6(Δ180) and cdc6(Δ240), were amplified from WT cdc6 and subcloned into pCS2(+) vector. The coding sequence of cdc6tsu21cd was amplified from cdc6tsu21cd mutant embryos and cloned into pCS2(+) vector. To validate the efficiency of two cdc6 morpholinos, a fragment containing 5′ untranslated region (5′-UTR) and 5′ part of coding sequence of cdc6 was amplified with the forward primer (5′-CGGAATTCTCAGGAGCAGAGAAACTA-3′) and the reverse primer (5′- TCCCCGCGGAGCGAGTGCTGGGCATTT-3′) and fused to the coding sequence of egfp, which were together inserted into pEGFP-N3 vector.

Capped mRNAs were synthesized using Sp6 mMessage mMachine Kit (Ambion) and purified using RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer‘s instructions. Two morpholinos, cdc6-MO1 (5′-AAAGCTGTAGTTTCTCTGCTCCTGA-3′) and cdc6-MO2 (5′-CGAGTGCTGGGCATTTTTATGTTTA-3′) were designed to inhibit Cdc6 translation, which were synthesized by Gene Tools, LLC. And std MO (5′-CCTCTTACCTCAGTTACAATTTATA-3′) was used as a control. Morpholinos and mRNAs were individually injected into the yolk of one-cell stage embryos with the typical MPPI-2 quantitative injection equipment at indicated doses and collected for analysis at later stages.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization and real-time quantitative RT-PCR

A fragment containing 3′-UTR and 3′-part of coding sequence of cdc6 was amplified with the forward primer (5′-AGGACAGACTCACACAGGTA-3′) and the reverse primer (5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGGTAATAGCAGCCAATGTCAAC-3′) and used for synthesizing Digoxigenin-labeled antisense RNA probe. Whole-mount in situ hybridization was performed using the commonly used protocol.

Total RNAs from embryos were used for real-time quantitative PCR. The primer sequences for analyzed genes were: for cdc6, 5′-CAGGCACGATTGGAGAAGTA-3′ (forward) and 5′-AAAGTTGAGCAGTTTGGGAC-3′ (reverse); for β-actin, 5′-ATGGATGATGAAATTGCCGCAC-3′ (forward) and 5′-ACCATCACCAGA GTCCATCACG-3′ (reverse); for tp53, 5′-ATGGATTTAGGCTCAGGTTC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTTATAGATGGCAGTGGCTC-3′ (reverse); for bbc3, 5′-ACAGTTGGATCGTGCCTTGC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GGTCTGGCTTTCTCCTTTGC-3′ (reverse); for stag1, 5′-TTCTCAGGGATTCACGATGC-3′ (forward) and 5′-ATAGTAGGATGGATAAACACAAA-3′ (reverse); for cenpF, 5′-GGTGAGCCATAAGGACATTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTGAACACTTAGAAACCGACT-3′ (reverse); for aspm, 5′-AGGTCGGAGACTAAGGGATT-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGCGGCGATGTAACCAAGAT-3′ (reverse).

Cell cycle analysis

The cell cycle analysis was performed as before (36). Briefly, embryos were dechorionated at desired stages by pronase treatment and deyolked by pipetting with a 200-μl tip. For preparing single-cell suspension, embryos were incubated in 1 ml of 0.25% trypsin at 28 °C for 30 min with triturating repetitively using a 1-ml tip followed by adding 0.5 ml DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum to stop the activity of trypsin. The homogenates were passed through a 40-μm mesh filter (BD, no. 352235) to get single-cell suspension. The cells were collected by centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 3 min and resuspended with 0.25 ml of PBS followed by fixation with 0.75 ml of cold ethanol at 4 °C overnight. The fixed cells were precipitated and resuspended with 500 μl of propidium iodide solution (0.1 mg/ml propidium iodide, 0.1% sodium citrate, 100 μg/ml RNase A, and 0.0002% Triton X-100) followed by analysis using the BD FACS Aria II flow cytometer. For tsu4305 mutants and WT siblings at 22 and 24 hpf, 15 embryos were used for each group. For embryos at 20 hpf, the embryos were digested individually into single-cell suspension and genotyping was performed before further analysis. Each group contained two to three embryos.

Western blot

For preparing antibody against zebrafish Cdc6, the full-length coding sequence of zebrafish cdc6 was cloned into the expression vector pET-15b. The recombinant plasmid was transformed into Escherichiacoli BL21 cells and expression was induced by adding IPTG at 1 mM for 6 h at 16 °C. The recombinant protein was purified with Ni-affinity chromatography and injected into rabbits at 500 μg per time as antigen. After four times of immunity, the rabbits were killed to collect blood. Serums were gathered through deposition and centrifugation of blood. The antibody against zebrafish Cdc6 was purified by antigen coupled affinity chromatography. The antibody was dialyzed, aliquotted and stored at −80 °C.

Embryos were dechorionated at desired stages and deyolked by pipetting with a 200-μl tip. Cells were collected by centrifugation at 3, 000 rpm for 3 min and lysed in TNE buffer for 30 min at 4 °C followed by centrifugation at 12 000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was added SDS loading buffer and boiled for 10 min. The used primary antibodies were: anti-actin (Santa Cruz, I-19, 1: 1000), anti-Cdk1 (Santa Cruz, sc-54, 1: 1000), anti-p-Cdk1(CST, 9111, 1: 1000), anti-Cdk2 (Millipore, 05-596, 1: 1000), anti-Flag (MBL, M185-L, 1: 1000), anti-γ-H2A.X (CST, no. 9718, 1: 1000), and anti-zebrafish Cdc6 (home-made, 1: 5000). The used secondary antibodies were HRP-conjugated anti-mouse (GE, NA931-1ML, 1: 5000), HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit (GE, NA934-1ML, 1: 5000) or HRP-conjugated anti-goat (Jackson ImmunoResearch, 1: 5000).

TUNEL, BrdU incorporation and immunostaining assays

For detecting apoptosis, TUNEL assay was performed by using ApopTag Red In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit (Millipore, S7165) according to the manufacturer‘s instruction.

For BrdU incorporation assays, embryos at 23 hpf were transferred to Holtfreter‘s solution containing 10 mM BrdUTP and incubated for 20 min on ice, and then displaced to fresh Holtfreter‘s solution and incubated at 30°C for 20 min or 1 h, followed by fixation in 4% polyformaldehyde. Other procedures for BrdU incorporation and immunstaining assays were similar unless other stated. Briefly, embryos fixed in 4% polyformaldehyde were dehydrated with methanol and stored at −20 °C overnight, followed by rehydration in PBST (1XPBS, 0.5% Triton X-100). The embryos were then permeabilized in acetone for 7 min at −20 °C and washed three times with PBST. For BrdU immunostaining, embryos were treated in 2M HCl for 1 h at room temperature followed by washing with PBST. Next, embryos were incubated in the block solution (1% BSA, 10% serum in 0.5% PBST) for 1 h at room temperature, and transferred to the block solution containing corresponding primary antibody for incubation overnight at 4 °C. After rinsed four times for 15 min each in PBST, the embryos were incubated in the block solution containing a secondary antibody for 2 h at room temperature, followed by washing four times for 15 min each in PBST. The used antibodies were: primary anti-BrdU (Santa Cruz, sc-32323, 1: 100), anti-active caspase3 (BD Biosciences, 559565, 1: 500), primary anti-α-tubulin antibodies (Sigma, T5168, 1: 100) and secondary antibodies conjugated with DyLight Fluorescent Dyes (488/549) (Jackson ImmunoResearch, 1: 200). The immunostained embryos were observed under Zeiss710 or Zeiss710 META confocal microscope.

Statistical analysis

Data averaged from multiple samples were presented as mean plus standard deviation (mean ± SD). Significance of difference was analyzed by Student’s t-test.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material is available at HMG online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Wei Wu (Tsinghua University) for providing Cdk1 and phosphorylated Cdk antibodies, and Dr Yeguang Chen (Tsinghua University) for providing Cdk2 antibody. We also thank the other members of Meng Lab for assistance and discussion and staff at Cell Facility in Tsinghua Center of Biomedical Analysis for assistance with imaging and cell sorting.

Conflict of Interest statement. None declared.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 31330052 and 31590832) and from Major Science Programs of China (nos. 2012CB945101 and 2011CB943800). Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by the grant (#31330052) from the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

References

- 1. DePamphilis M.L., Blow J.J., Ghosh S., Saha T., Noguchi K., Vassilev A. (2006) Regulating the licensing of DNA replication origins in metazoa. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 18, 231–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. de Munnik S.A., Hoefsloot E.H., Roukema J., Schoots J., Knoers N.V., Brunner H.G., Jackson A.P., Bongers E.M. (2015) Meier-Gorlin syndrome. Orphanet J. Rare Dis., 10, 114.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bicknell L.S., Bongers E.M., Leitch A., Brown S., Schoots J., Harley M.E., Aftimos S., Al-Aama J.Y., Bober M., Brown P.A.. et al. (2011) Mutations in the pre-replication complex cause Meier-Gorlin syndrome. Nat. Genet., 43, 356–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. de Munnik S.A., Otten B.J., Schoots J., Bicknell L.S., Aftimos S., Al-Aama J.Y., van Bever Y., Bober M.B., Borm G.F., Clayton-Smith J.. et al. (2012) Meier-Gorlin syndrome: growth and secondary sexual development of a microcephalic primordial dwarfism disorder. Am. J. Med. Genet. A, 158A, 2733–2742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kan Q., Jinno S., Yamamoto H., Kobayashi K., Okayama H. (2008) ATP-dependent activation of p21WAF1/CIP1-associated Cdk2 by Cdc6. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 105, 4757–4762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Uranbileg B., Yamamoto H., Park J.H., Mohanty A.R., Arakawa-Takeuchi S., Jinno S., Okayama H. (2012) Cdc6 protein activates p27KIP1-bound Cdk2 protein only after the bound p27 protein undergoes C-terminal phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem., 287, 6275–6283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Niimi S., Arakawa-Takeuchi S., Uranbileg B., Park J.H., Jinno S., Okayama H. (2012) Cdc6 protein obstructs apoptosome assembly and consequent cell death by forming stable complexes with activated Apaf-1 molecules. J. Biol. Chem., 287, 18573–18583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Illenye S., Heintz N.H. (2004) Functional analysis of bacterial artificial chromosomes in mammalian cells: mouse Cdc6 is associated with the mitotic spindle apparatus. Genomics, 83, 66–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Anger M., Stein P., Schultz R.M. (2005) CDC6 requirement for spindle formation during maturation of mouse oocytes. Biol. Reprod., 72, 188–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Narasimhachar Y., Webster D.R., Gard D.L., Coue M. (2012) Cdc6 is required for meiotic spindle assembly in Xenopus oocytes. Cell Cycle, 11, 524–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Petrakis T.G., Vougas K., Gorgoulis V.G. (2012) Cdc6: a multi-functional molecular switch with critical role in carcinogenesis. Transcription, 3, 124–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huang S., Xu X., Wang G., Lu G., Xie W., Tao W., Zhang H., Jiang Q., Zhang C. (2016) DNA replication initiator Cdc6 also regulates ribosomal DNA transcription initiation. J. Cell. Sci., 129, 1429–1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ohta S., Koide M., Tokuyama T., Yokota N., Nishizawa S., Namba H. (2001) Cdc6 expression as a marker of proliferative activity in brain tumors. Oncol. Rep., 8, 1063–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Karakaidos P., Taraviras S., Vassiliou L.V., Zacharatos P., Kastrinakis N.G., Kougiou D., Kouloukoussa M., Nishitani H., Papavassiliou A.G., Lygerou Z.. et al. (2004) Overexpression of the replication licensing regulators hCdt1 and hCdc6 characterizes a subset of non-small-cell lung carcinomas: synergistic effect with mutant p53 on tumor growth and chromosomal instability–evidence of E2F-1 transcriptional control over hCdt1. Am. J. Pathol., 165, 1351–1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Murphy N., Ring M., Heffron C.C., King B., Killalea A.G., Hughes C., Martin C.M., McGuinness E., Sheils O., O'Leary J.J. (2005) p16INK4A, CDC6, and MCM5: predictive biomarkers in cervical preinvasive neoplasia and cervical cancer. J. Clin. Pathol., 58, 525–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Deng Y., Jiang L., Wang Y., Xi Q., Zhong J., Liu J., Yang S., Liu R., Wang J., Huang M.. et al. (2016) High expression of CDC6 is associated with accelerated cell proliferation and poor prognosis of epithelial ovarian cancer. Pathol. Res. Pract., 212, 239–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mahadevappa R., Neves H., Yuen S.M., Bai Y., McCrudden C.M., Yuen H.F., Wen Q., Zhang S.D., Kwok H.F. (2017) The prognostic significance of Cdc6 and Cdt1 in breast cancer. Sci. Rep., 7, 985.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen S., Chen X., Xie G., He Y., Yan D., Zheng D., Li S., Fu X., Li Y., Pang X.. et al. (2016) Cdc6 contributes to cisplatin-resistance by activation of ATR-Chk1 pathway in bladder cancer cells. Oncotarget, 7, 40362–40376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen C.H., Lin D.S., Cheng C.W., Lin C.J., Lo Y.K., Yen C.C., Lee A.Y., Hsiao C.D. (2014) Cdc6 cooperates with c-Myc to promote genome instability and epithelial to mesenchymal transition EMT in zebrafish. Oncotarget, 5, 6300–6311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhou Y., Zon L.I. (2011) The zon laboratory guide to positional cloning in zebrafish. Methods Cell Biol., 104, 287–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Piatti S., Lengauer C., Nasmyth K. (1995) Cdc6 is an unstable protein whose de novo synthesis in G1 is important for the onset of S phase and for preventing a “reductional” anaphase in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J., 14, 3788–3799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McInerny C.J., Partridge J.F., Mikesell G.E., Creemer D.P., Breeden L.L. (1997) A novel Mcm1-dependent element in the SWI4, CLN3, CDC6, and CDC47 promoters activates M/G1-specific transcription. Genes Dev., 11, 1277–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Norbury C., Blow J., Nurse P. (1991) Regulatory phosphorylation of the p34cdc2 protein kinase in vertebrates. EMBO J., 10, 3321–3329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gu Y., Rosenblatt J., Morgan D.O. (1992) Cell cycle regulation of CDK2 activity by phosphorylation of Thr160 and Tyr15. EMBO J., 11, 3995–4005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kinner A., Wu W., Staudt C., Iliakis G. (2008) Gamma-H2AX in recognition and signaling of DNA double-strand breaks in the context of chromatin. Nucleic Acids Res., 36, 5678–5694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Perkins G., Diffley J.F. (1998) Nucleotide-dependent prereplicative complex assembly by Cdc6p, a homolog of eukaryotic and prokaryotic clamp-loaders. Mol. Cell, 2, 23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Weinreich M., Liang C., Stillman B. (1999) The Cdc6p nucleotide-binding motif is required for loading mcm proteins onto chromatin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 96, 441–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Petersen B.O., Wagener C., Marinoni F., Kramer E.R., Melixetian M., Lazzerini Denchi E., Gieffers C., Matteucci C., Peters J.M., Helin K. (2000) Cell cycle- and cell growth-regulated proteolysis of mammalian CDC6 is dependent on APC-CDH1. Genes Dev., 14, 2330–2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Petersen B.O., Lukas J., Sorensen C.S., Bartek J., Helin K. (1999) Phosphorylation of mammalian CDC6 by cyclin A/CDK2 regulates its subcellular localization. EMBO J., 18, 396–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pfleger C.M., Kirschner M.W. (2000) The KEN box: an APC recognition signal distinct from the D box targeted by Cdh1. Genes Dev., 14, 655–665. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Orban L., Sreenivasan R., Olsson P.E. (2009) Long and winding roads: testis differentiation in zebrafish. Mol. Cell Endocrinol., 312, 35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gerhard G.S., Kauffman E.J., Wang X., Stewart R., Moore J.L., Kasales C.J., Demidenko E., Cheng K.C. (2002) Life spans and senescent phenotypes in two strains of Zebrafish (Danio rerio). Exp. Gerontol., 37, 1055–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liu J., Smith C.L., DeRyckere D., DeAngelis K., Martin G.S., Berger J.M. (2000) Structure and function of Cdc6/Cdc18: implications for origin recognition and checkpoint control. Mol. Cell, 6, 637–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jin P., Tian T., Sun Z., Meng A. (2004) Generation of mutants with developmental defects in zebrafish by ENU mutagenesis. Chin. Sci. Bull., 49, 2154–2158. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chen J., Wu X., Yao L., Yan L., Zhang L., Qiu J., Liu X., Jia S., Meng A. (2017) Impairment of cargo transportation caused by gbf1 mutation disrupts vascular integrity and causes hemorrhage in zebrafish embryos. J Biol. Chem., 292, 2315–2327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhao X., Zhao L., Tian T., Zhang Y., Tong J., Zheng X., Meng A. (2010) Interruption of cenph causes mitotic failure and embryonic death, and its haploinsufficiency suppresses cancer in zebrafish. J. Biol. Chem., 285, 27924–27934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.