Abstract

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is one of many neurodegenerative diseases termed synucleinopathies, neuropathologically defined by inclusions containing aggregated α-synuclein (αS). αS gene (SNCA) mutations can directly cause autosomal dominant PD. In vitro studies demonstrated that SNCA missense mutations may either enhance or diminish αS aggregation but cross-seeding of mutant and wild-type αS proteins appear to reduce aggregation efficiency. Here, we extended these studies by assessing the effects of seeded αS aggregation in αS transgenic mice through intracerebral or peripheral injection of various mutant αS fibrils. We observed modestly decreased time to paralysis in mice transgenic for human A53T αS (line M83) intramuscularly injected with H50Q, G51D or A53E αS fibrils relative to wild-type αS fibrils. Conversely, E46K αS fibril seeding was significantly delayed and less efficient in the same experimental paradigm. However, the amount and distribution of αS inclusions in the central nervous system were similar for all αS fibril muscle injected mice that developed paralysis. Mice transgenic for human αS (line M20) injected in the hippocampus with wild-type, H50Q, G51D or A53E αS fibrils displayed induction of αS inclusion pathology that increased and spread over time. By comparison, induction of αS aggregation following the intrahippocampal injection of E46K αS fibrils in M20 mice was much less efficient. These findings show that H50Q, G51D or A53E can efficiently cross-seed and induce αS pathology in vivo. In contrast, E46K αS fibrils are intrinsically inefficient at seeding αS inclusion pathology. Consistent with previous in vitro studies, E46K αS polymers are likely distinct aggregated conformers that may represent a unique prion-like strain of αS.

Introduction

Alterations of the SNCA gene, either owing to increased copy number of the entire gene or missense mutations within the N-terminal region of the encoded protein, are a known cause of autosomal dominant Parkinson’s disease (PD; OMIM # 605543 and 168601, respectively) or the related disorder dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB; OMIM # 127750) (1–10). SNCA encodes the 140 amino acid lipid-binding protein, α-synuclein (αS), which is predominantly presynaptic (11). The natively unstructured αS can adopt an α-helical conformation, via imperfect KTKEGV repeats in its N-terminal region, allowing it to bind to lipids (12). However, αS may misfold into the β-pleated sheet structure, known as amyloid, which is aggregate prone. This form of αS polymerizes into fibrillar structures that coalesce to form pathological inclusions which are a hallmark of a class of neurodegenerative diseases termed synucleinopathies (13–16). Synucleinopathies include PD, DLB and multiple system atrophy (MSA; OMIM # 146500), but αS pathology may also occur in a subset of other neurodegenerative disorders including Alzheimer’s disease (OMIM # 104310) (13–20).

In vitro, the H50Q and A53T αS mutations were shown to accelerate (21–27), whereas G51D and A53E αS mutations slow down aggregation of αS compared with the wild-type protein (26–30). The effects of the A30P and the E46K αS mutations on in vitro aggregation have also been investigated, but reports have displayed conflicting results as to whether they accelerate (25,31–35) or decelerate αS aggregation (27,36,37).

The polymerization of αS into amyloid fibrils is nucleation dependent (38) and the in vivo aggregation of endogenous αS can be induced by the introduction of preformed αS amyloidogenic seeds by a prion-like conformation templating mechanism (39–42). Owing to the autosomal dominant nature of the SNCA missense mutations patients carry one wild-type allele, yielding a situation where cross-seeding events between mutant and wild-type proteins likely occur. The effects of such cross-seeding have predominantly been studied in vitro (27,34). Dhavale et al. showed that mutant fibrils can induce the aggregation of wild-type αS, however, the rate at which this occurs is significantly reduced compared with homologous seeding (27). Nonetheless, the relevance of these in vitro studies to an in vivo setting and human conditions is uncertain. Herein, we aim to extend these studies into relevant models of synucleinopathy by assessing the effect of induced αS aggregation by seeding with mutant αS fibrils in αS transgenic mouse models.

Results

In the current study, we aimed to assess the relative abilities of mutant αS fibrils to induce aggregation of αS in vivo. To achieve this, we utilized two well-established seeding paradigms; injection of αS fibrils either directly into the brain, or peripherally, in αS transgenic mice (43–46). We used different lines of mice for each injection paradigm. Mice transgenic for human wild-type (M20 line) and human A53T (M83 line) αS were used for the intrahippocampal and intramuscular injections, respectively (47). The M20 mice were used for the cerebral injections as these mice never intrinsically develop αS inclusion pathology (47). M83 mice were used for intramuscular injection of preformed αS seeds as the subsequent induction of αS aggregation and motor impairment is much more robust in these mice, resulting in a highly reproducible behavior readout (46).

M83 mice injected bilaterally in the gastrocnemius muscle with αS fibrils were allowed to age until the presentation of motor impairment that progressed to paralysis. Some mice had to be sacrificed early owing to fight wounds and were consequently not included in the subsequent analysis (final n = 6–9/group). In this experimental paradigm, the neuronal retrograde transport of αS fibril seeds, as previously demonstrated by the significant delay or complete prevention of central nervous system (CNS) αS pathology by the prior severing of the sciatic nerve (46), is the primary mechanism of CNS neuroinvasion, although additional transport mechanisms such as hematogenous spread also may contribute to this process.

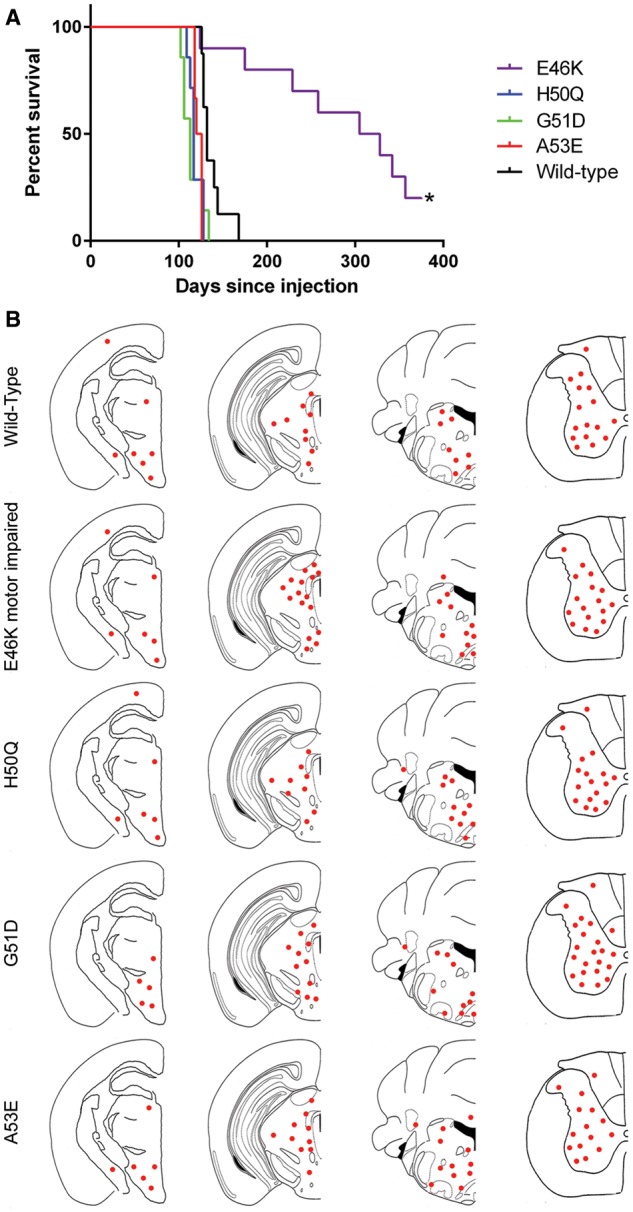

Mice injected with wild-type αS fibrils displayed motor impairment between 126 and 168 days post-injection (Fig. 1A). The time between injection and end-stage was similar between mice injected with H50Q, G51D and A53E αS fibrils, with all mice developing motor impairment between 100 and 135 days (Fig. 1A). Those injected with E46K αS fibrils showed greater variability in the onset of paralysis (Fig. 1A). One mouse displayed paralysis at 124 days post-injection, however, 6 were motor impaired much later (229–357 days post-injection) and 2 did not display any motor phenotype after injection of E46K αS fibrils, and were sacrificed for analysis at 375 days post-injection. All of the survival curves of mice injected with mutant αS fibrils were significantly different from the curve of wild-type αS fibril injected mice; H50Q, G51D and A53E curves were slightly but significantly earlier than the wild-type curve (P = 0.0029, 0.0074 and 0.0008, respectively), and the E46K curve was significantly later than wild-type (P = 0.0002).

Figure 1.

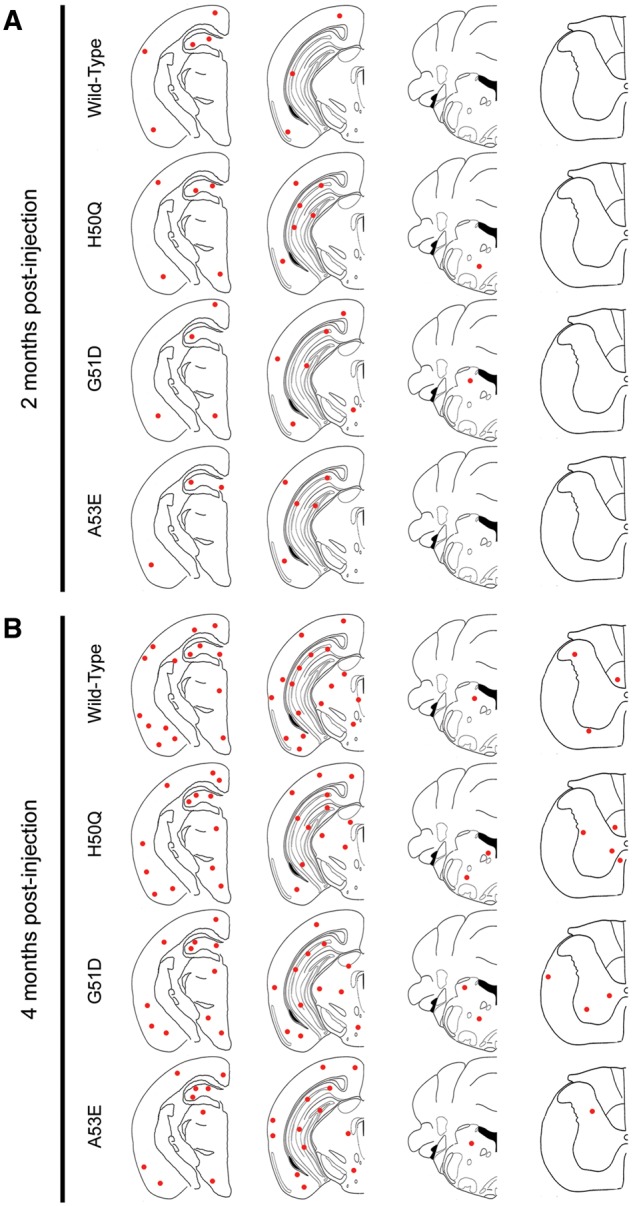

Assessment of motor impairment and distribution of αS inclusion pathology in M83 mice following intramuscular injection of mutant αS fibrils. (A) Survival curve of M83 mice following intramuscular injection of human wild-type, E46K, H50Q, G51D or A53E αS fibrils (n = 6–9/group). Asterisk indicates the time at which remaining mice were sacrificed. All mutant survival curves are significantly different from wild-type. (B) Distribution maps of LS4–2G12 positive αS pathology in αS fibril injected M83 mice. LS4–2G12 detects pSer129 αS. Two mice injected with E46K αS fibrils did not display αS inclusion pathology and are not represented in this figure.

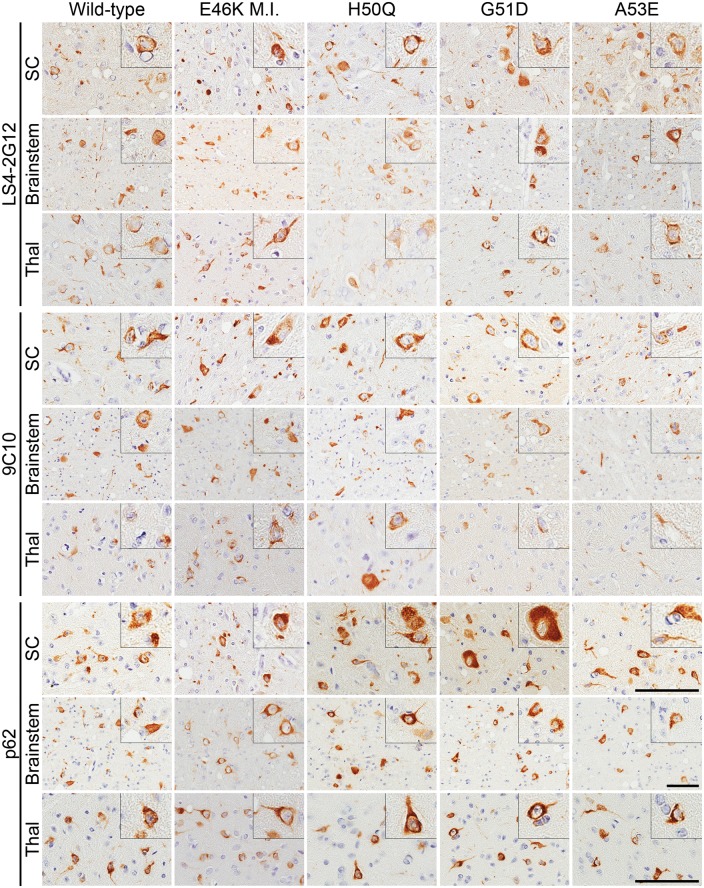

Analysis of the amount and distribution of αS inclusions was assessed by immunostaining using antibody LS4–2G12, which specifically detects αS phosphorylated at serine 129 (pSer129 αS), a marker of αS inclusion pathology (Figs 1B and 2) (48). We observed similar distributions of αS pathology in all of the mice that were paralyzed, with abundant αS inclusions throughout the spinal cord, brainstem, periaqueductal gray region, midbrain and thalamus. The morphology of the αS inclusions was also similar across the different cohorts of mice, with frequent perikaryal and neuritic inclusions observed in all injection groups. Conversely, the E46K αS fibril injected mice that were sacrificed >12 months post-injection without motor impairment displayed a paucity of αS inclusions (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1). The authenticity of αS inclusions was confirmed by immunostaining using our newly developed antibody 9C10 (N-terminus of αS) and the general inclusion marker, p62 (Fig. 2; Supplementary Material, Fig. S2) as well as anti-human αS antibody Syn 211 and the previously established αS N-terminal-specific antibody Syn 506 (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3). In addition, we showed that some of the inclusions were Thioflavin S-positive and silver stained (Supplementary Material, Fig. S4). As controls, we have previously shown that M83 mice injected in the muscle with immunogenic molecules including lipopolysaccharide (46) and keyhole limpet hemocyanin, or the αS-like molecule β-synuclein (49) do not induce αS aggregation or motor impairment.

Figure 2.

αS inclusion pathology in M83 mice injected in the gastrocnemius muscle with wild-type or mutant αS fibrils. Representative immunohistochemistry images of spinal cord (SC), brainstem and thalamus (Thal) of M83 mice injected intramuscularly with wild-type, E46K, H50Q, G51D or A53E αS fibrils. Only motor impaired E46K (E46K M.I.) αS fibril injected M83 mice are represented. LS4–2G12 detects pSer129 αS, 9C10 detects the N-terminus of αS and p62 is a general inclusion marker. Scale bars = 50 μm, or 100 μm (insets) for each respective region shown.

For our direct brain injection study, M20 mice were bilaterally injected in the hippocampus with αS fibrils then sacrificed at either 2 or 4 months post-injection (n = 4–6/group) for the wild-type, H50Q, G51D and A53E αS fibril injected mice. Owing to the latency to paralysis onset in the E46K αS fibril muscle injected mice, we decided to increase the time points of the mice injected in the hippocampus with E46K αS fibrils, and aged them for 4, 6 or 8 months post-injection (n = 2–4/group). It is likely that the cycle of conformational templating of endogenous and transgenic αS by the injected amyloidogenic αS seeds followed by transport of the induced aggregated αS and subsequent conformational templating in more distally connected brain regions results in the spread of inclusion pathology in this model. However, the diffusion of αS seeds from the injection site may also contribute to the spatial induction of αS inclusion pathology. Nevertheless, even if both mechanisms are involved, this model can be used to assess the relative efficiencies of different types of αS seeds in the spatial and temporal induction of αS inclusion pathology.

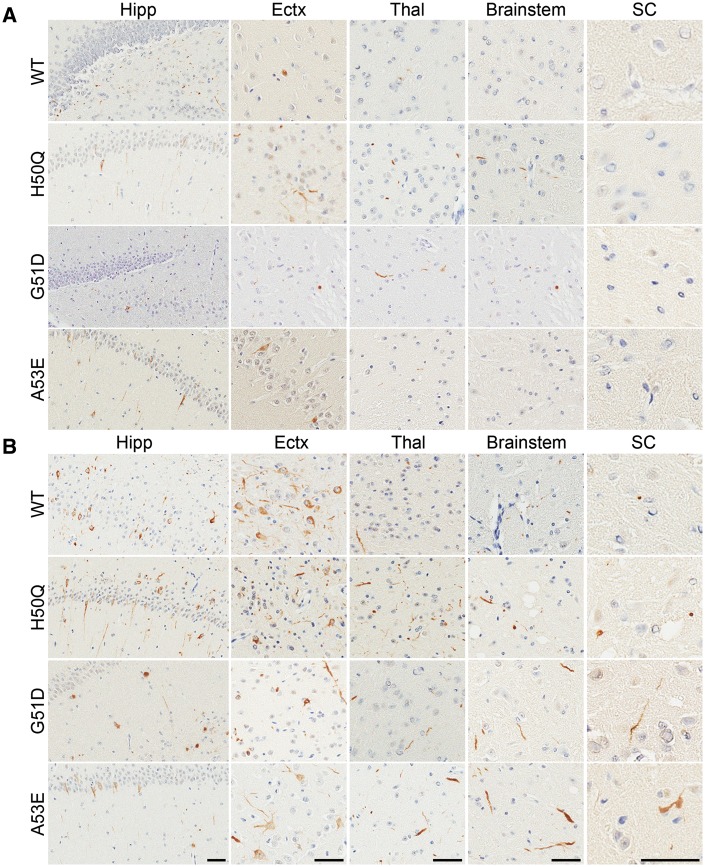

At 2 months post-injection, wild-type, H50Q, G51D and A53E αS fibril injected M20 mice all displayed sparse to moderate αS pathology in the hippocampus and cortex (Figs 3A and 4A;Supplementary Material, Figs S5 and S6). Additionally, H50Q and G51D αS fibril injected M20 mice also displayed some αS inclusions in the brainstem, as well as in the thalamus of G51D injected mice. By 4 months post-injection, the amount of αS inclusion pathology had dramatically increased in all of these mice. There was robust αS pathology in the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex in each group and lower amounts in the thalamus, brainstem and spinal cord. The wild-type αS fibril injected M20 mice displayed the most αS inclusions in the cortex, while A53E αS fibril injected mice appeared to have less αS pathology overall. The morphologies of the inclusions were very similar in these cohorts of mice, with mostly neurites in areas with sparse to moderate pathology and a combination of perikaryal and neuritic inclusions in regions with more dense pathology.

Figure 3.

Assessment of αS inclusion pathology in M20 mice following intrahippocampal injection of human wild-type, H50Q, G51D or A53E mutant αS fibrils. Distribution maps of LS4–2G12 immunopositive αS staining in M20 mice at 2 months (A) and 4 months (B) post-intrahippocampal injection of human wild-type, H50Q, G51D or A53E αS fibrils (n = 4–6 mice/group).

Figure 4.

αS inclusion pathology in M20 mice following intrahippocampal injection of human wild-type, H50Q, G51D or A53E mutant αS fibrils. Representative LS4–2G12 immunostaining images of the hippocampus (Hipp), entorhinal cortex (Ectx), thalamus (Thal), brainstem and spinal cord (SC) of M20 mice 2 months (A) or 4 months (B) post-intrahippocampal injection of human wild-type, H50Q, G51D or A53E αS fibrils. Scale bars = 50 μm for each respective region shown.

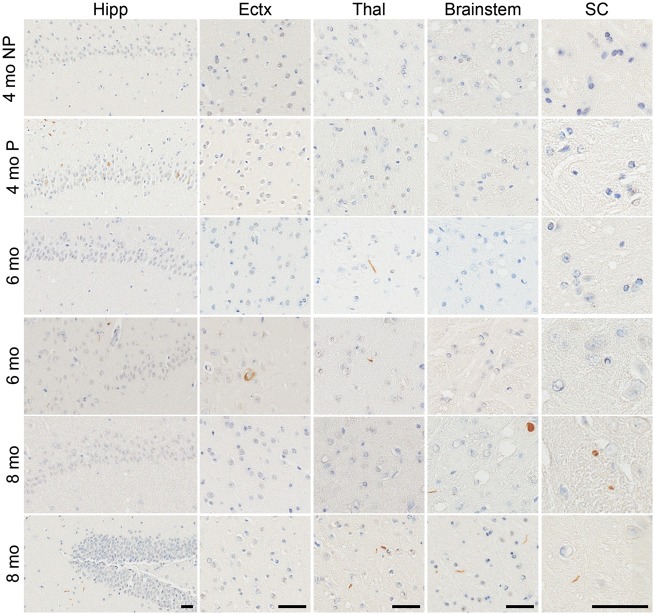

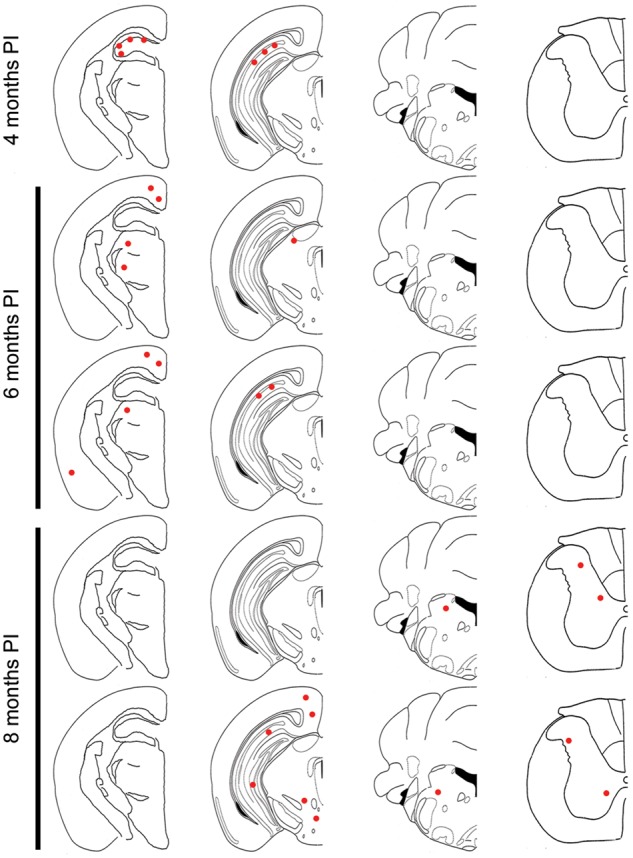

Conversely, the E46K αS fibrils demonstrated very low efficiency in the induction of αS inclusion pathology in M20 mice, with only 1 out of 4 mice displaying any αS inclusions at 4 months post-injection (Figs 5and 6; Supplementary Material, Figs S7 and S8) which were limited to the hippocampus. There was some spread of αS inclusion pathology over time, with αS inclusions identified in the thalamus and cortex in both M20 mice analyzed at the 6 month post-injection time point, however, there was a reduction in the amount of pathology observed in the hippocampus. There was further spread in the 2 M20 mice sacrificed at 8 months post-injection to the brainstem and spinal cord, and one of these mice also displayed αS inclusions in the hippocampus, cortex and thalamus whereas the other did not. Overall the amount of αS inclusions in the E46K αS fibril injected M20 mice were sparse and we observed both neuritic and perikaryal inclusions. As controls, we have previously shown that injection of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) into the cerebrum of M20 mice does not induce αS inclusion pathology (44,50,51).

Figure 5.

Assessment of αS inclusion pathology in M20 mice following intrahippocampal injection of E46K αS fibrils. Distribution maps of LS4–2G12 immunopositive αS staining in M20 mice at 4 months (only one out of the four mice displayed αS inclusion pathology at this time point and is represented by the distribution map), 6 months (n = 2) and 8 months (n = 2) post-intrahippocampal injection of E46K αS fibrils. PI, post-injection.

Figure 6.

αS inclusion pathology in M20 mice following intrahippocampal injection of E46K αS fibrils. Representative LS4–2G12 immunostaining images of the hippocampus (Hipp), entorhinal cortex (Ectx), thalamus (Thal), brainstem and spinal cord (SC) of M20 mice 4, 6 or 8 months post-intrahippocampal injection of E46K αS fibrils. Scale bars = 50 μm for each respective region shown. At 4 months, NP, no pathology present (n = 3); P, pathology present (n = 1).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the effects of seeding induced αS aggregation in αS transgenic mice by various mutant αS fibrils versus wild-type αS fibrils. We employed two well-characterized injection paradigms; intrahippocampal and intramuscular injection of αS fibrils (43–46). The use of M20 mice in the hippocampal injection experiment allows us to assess the abilities of the mutant αS fibrils to cross-seed wild-type αS, which is relevant to human disease as SNCA mutation carriers are heterozygous for the missense mutations. It would have been ideal to also use M20 mice for the muscle injection experiment, however, these mice do not develop robust αS inclusion pathology or motor impairment following this type of injection (46), making them unsuitable for this experiment. Therefore, we injected A53T αS transgenic (M83) mice, which have been extensively studied in the field, in the gastrocnemius muscle that has been previously shown to result in paralysis and CNS αS inclusion pathology (46). Despite the introduction of another variable when using the M83 mice, we were still able to assess the abilities of the mutant αS fibrils to induce αS aggregation and paralysis relative to the wild-type protein.

In our peripheral injection study, the time from injection to paralysis was slightly but significantly shorter for H50Q, G51D and A53E αS compared with wild-type αS fibril injected mice, all of which became motor impaired within a very narrow time range, whereas paralysis of E46K αS fibril injected mice was significantly delayed, highly variable and not completely penetrant. The distributions of αS inclusions throughout the CNS of the paralyzed M83 mice were comparable between injection groups as these mice were all analyzed at endstage, and the 2 M83 mice injected with E46K αS fibrils that remained healthy showed no αS inclusions upon examination. The delayed, variable, and incomplete seeding following intramuscular inoculation of E46K αS fibrils in M83 mice shows that this mutant is less potent at inducing αS aggregation in these mice. These experiments demonstrate the unique characteristics of this mutant compared with the other αS mutants assessed, as well as wild-type αS, which is likely linked to the distinct structural properties of aggregated E46K αS polymers that has been observed using many different types of ultrastructural and biophysical methods (31–34,52,53). One of these studies showed that the E46K mutation enhances the contacts between the amino- and carboxy-terminal regions of αS (52), which might result in different conformers of aggregated αS within E46K αS polymerized fibrils.

Following hippocampal injection of αS fibrils (wild-type, H50Q, G51D and A53E), M20 mice were sacrificed at 2 and 4 month time points. These M20 mice showed similar patterns of αS pathology that progressed with time, spreading throughout the neuraxis. While all of these M20 mice displayed spread of αS inclusion pathology in the CNS, the relative amounts of αS inclusions slightly differed. G51D and H50Q αS fibril injected mice displayed more widespread inclusions compared with wild-type, and although A53E αS fibril injected mice displayed a similar pattern of αS inclusions to wild-type αS fibril injected mice at 2 months post-injection, these mice had a lower density of αS inclusions at the 4 month time-point.

As the A53E mutation has been reported to slow the rate of αS aggregation in vitro (29,30) this provides a potential explanation for the reduction of αS pathology observed in the M20 mice injected in the hippocampus with A53E versus wild-type αS fibrils. In contrast, G51D was also shown to decrease αS fibril formation in vitro (26–28), however, induced more widespread αS inclusion pathology than wild-type αS fibrils at 2 months post-injection similar to that induced by H50Q αS fibrils, which was reported to accelerate fibril formation in vitro (22,26,27). This suggests that the rate at which the mutant protein aggregates is not necessarily a critical driving factor in the seeded formation and spread of αS inclusions in vivo.

As Dhavale et al. recently reported that cross-seeding of mutant and wild-type αS results in a reduction of aggregation in vitro (27), it would be expected to observe a reduction in the amount of αS inclusion pathology in the M20 mice injected with fibrillar αS mutants, if the in vitro findings were to predict outcomes in vivo. However, in the hippocampal injection of H50Q and G51D αS fibrils we observed more widespread αS inclusions compared with homotypic seeding, that being wild-type αS fibrils injected into M20 mice which express wild-type αS.

We also performed intrahippocampal injection of M20 mice with E46K αS fibrils, however, we analyzed these mice at later time points than the mice injected with the other mutant αS fibrils owing to the overall later onset of paralysis observed in the muscle injected M83 mice. Again, there was more variability in the induction of αS aggregation in the E46K αS fibril brain injected M20 mice, with only one out of the four mice showing any αS inclusions at 4 months post-injection, and which were restricted to the site of injection. Nevertheless, both sets of mice that were aged for 6 and 8 months post-injection displayed more αS inclusions upon analysis. These mice displayed spread of αS pathology to the thalamus and cortex at 6 months, and brainstem and spinal cord at 8 months post-injection. There also appeared to be some clearance of the αS inclusions over time, with one mouse at 6 months post-injection displaying no αS inclusions at the site of injection and one mouse at 8 months post-injection only displaying αS inclusions in the brainstem and spinal cord. These results suggest that E46K is the most inefficient of the tested mutants at inducing αS aggregation in vivo, despite its reported acceleration of αS fibrillization in vitro, in some cases (31–34). The inefficient induction of αS inclusion pathology by E46K αS preformed fibrillar seeds was also observed when directly injected in the brains of mice transgenic for human E46K αS (M47 line) (45) indicating that this property of the E46K mutant is not owing to heterologous protein incompatibility.

The discoveries of pathogenic αS missense mutations causal of neurodegeneration were seminal findings demonstrating the direct role of abnormal forms of αS in neuronal demise. However, synucleinopathies, even when associated with αS mutations, can present as a spectrum of clinical and pathological features, e.g. E46K mutation carriers often display REM sleep behavior disorder and dementia that are commonly seen in DLB patients (10,54) and G51D mutation carriers may present with autonomic dysfunction, and glial cytoplasmic inclusions that are defining features of MSA (3,19,20). We showed here that the effects of αS mutations on aggregation observed in vitro compared with the in vivo seeded induction of pathology can be divergent, such that a mutation that appears less prone to aggregate in vitro can still potently induce aggregation in seeded experimental paradigms in vivo. These differences might be explained by the many complex elements involved in the propagation of αS aggregates in vivo that include cellular uptake and release, relative stability of aggregated/misfolded αS, sequestration by cellular binding and efficiency in the recruitment of native αS protein by conformation templating. At this time, it is still unclear which of these steps is rate limiting in the in vivo spread of αS pathology, but these could be differentially affected for specific αS mutants, thus influencing the pathological and clinical presentations. The information derived from mutant forms of the αS protein may help to identify features of αS aggregation and propagation properties that could be potential targets for therapeutic intervention.

Materials and Methods

Recombinant αS expression, purification and fibril formation

The pRK172 bacterial expression vectors containing cDNA encoding wild-type, E46K, H50Q, G51D or A53E full-length human αS were generated as previously described (26,30,33,55). Plasmids were transformed into BL21 (DE3)/RIL Escherichia coli (E. coli; Agilent Technologies) and recombinant αS was purified from E. coli by size exclusion chromatography and subsequent anion exchange as previously described (33,55). Protein concentrations were determined by bicinchoninic acid assay using bovine serum albumin as the protein standard. Recombinant αS proteins (5 mg/ml in sterile PBS) were incubated at 37 °C with constant shaking at 1050 rpm (Thermomixer R, Eppendorf) for >48 h. Fibril formation was monitored by K114 [(trans, trans)-1-bromo-2,5-bis-(4-hydroxy)styrylbenzene] fluorometry as previously described (56). To prepare fibrils for injection, fibrils were diluted to 2 mg/ml in sterile PBS and sonicated in a water bath for 2 h. Sonicated fibrils were then aliquoted, stored at −80 °C and thawed when required. Each experiment in this study was performed using fibrils from the same preparation, limiting batch to batch variation.

Mouse lines

All procedures were performed according to the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Experimental Animals and were approved by the University of Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. M20 and M83 mice on the C57BL/C3H background were previously described (47). The M20 line is transgenic for wild-type αS and the M83 line is transgenic for αS with the pathogenic A53T mutation. All αS transgenic mice used in the studies were hemizygous.

Mouse injection procedures

For stereotaxic injection, hemizygous M20 mice (2–4 months of age) were anesthetized with 1–5% isoflurane and bilaterally injected in the hippocampus (coordinates from Bregma: anterior/posterior −2.2 mm, lateral ±1.6 mm, dorsal/ventral −1.2 mm) with 2 μl of mutant or wild-type αS fibrils (2 mg/ml) at a rate of 0.2 μl/min. Following injection, the needle was left in place for 5 min before removing. Mice were sacrificed at 2, 4, 6 or 8 months post-injection.

For muscle injection, hemizygous M83 mice (2–3 months of age; n = 10/group) were anesthetized with 1–5% isoflurane and bilaterally injected in the gastrocnemius muscle with 5 μl of αS fibrils (2 mg/ml). Muscle injected mice were sacrificed following the presentation of motor impairment that progressed to paralysis or at 375 days post injection, whichever came first.

Mice were humanely euthanized by CO2, followed by cardiac perfusion of PBS/heparin. Brain and spinal cord were harvested and fixed in 70% ethanol/150 mM NaCl. Tissues were dehydrated and embedded in paraffin, then cut into 5 μm sections using a microtome.

Antibodies

LS4–2G12 is a mouse monoclonal antibody that detects pSer129 αS (48). Syn 211 is a mouse monoclonal antibody specific for human αS (57) and Syn 506 is a conformational anti-αS mouse monoclonal antibody that preferentially detects αS in pathological inclusions (58,59). Mouse monoclonal antibody 9C10 detects αS residues 2–21. Rabbit polyclonal antibody, p62 is a general inclusion marker (SQSTM1; Proteintech).

Immunohistochemistry

Sections were deparaffinized with xylene then rehydrated with a descending series of ethanols (100–70%). Sections underwent antigen retrieval in a 0.05% Tween-20 steam bath for 30 min then endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched with 1.5% hydrogen peroxide/0.005% Triton X-100/PBS for 20 min. Sections were blocked with 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS)/100 mM Tris, pH 7.6, and then incubated in primary antibody diluted in 2% FBS/100 mM Tris, pH 7.6 overnight at 4 °C. The following day, sections were incubated in biotinylated horse anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Vector Laboratories) diluted in 2% FBS/100 mM Tris, pH 7.6 for 1 h at room temperature. Sections were then incubated in tertiary antibody (VECTASTAIN ABC kit, Vector Laboratories) diluted in 2% FBS/100 mM Tris, pH 7.6, for 1 h at room temperature and reactivity was visualized using the chromogen 3, 3’-diaminobenzidine. Sections were counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin and dehydrated using an ascending series of ethanols (70–100%). Sections were cleared in xylene, coverslipped using cytoseal, and then scanned using an Aperio ScanScope CS (40× magnification; Aperio Technologies Inc.).

Thioflavin S staining

After tissue sections were rehydrated as described above, sections were rinsed in PBS and then treated with Millipore autofluorescent agent (Millipore) for 5 min. Sections were washed three times in 40% ethanol/PBS and kept in the dark for all subsequent steps. Sections were incubated in 0.0125% Thioflavin S in 50% ethanol/PBS for 3 min and then washed in 50% ethanol/PBS for 30 s. Following PBS washes, sections were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and mounted using Fluoromount-G (Southern Biotech).

Campbell-Switzer silver stain

For silver staining, tissue sections were rehydrated as described above and developed with adapted Campbell-Switzer silver stain as previously described (49).

Double immunofluorescence analysis

Tissue sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated, and antigen retrieval was performed as described in the immunohistochemistry methods. Sections were blocked with 5% dry milk/100 mM Tris pH 7.6. Primary antibodies were diluted in blocking solution and applied to sections for overnight incubation at 4 °C. Sections were washed with 100 mM Tris pH 7.6 and secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 or 594 fluorophores (Life Technologies) were diluted in blocking solution and applied to sections for 2 h at room temperature in the dark. Sections were then treated with Sudan black to block lipofuscin autofluorescence. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (Pierce) and sections were mounted using Fluoromount-G (SouthernBiotech). Pictures were obtained using an Olympus BX51 fluorescent microscope mounted with a DP71 digital camera (Olympus) and images were overlaid using Photoshop software.

Quantification of staining and statistical analyses

Scanned images of LS4–2G12 stained sections were opened in ImageScope TM software (Leica Biosystems) and a single user blinded to conditions completed a distribution map (as shown in Figs 1, 3 and 5) for each mouse, which indicates the amount and location of LS4–2G12 positive inclusions. The distribution maps were decoded and averaged for each treatment. Mice within a group that showed disparate pathology were not included in the averaged distribution map and are noted in the results. Bar graphs and survival curves were plotted, and statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism v5.03 software.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material is available at HMG online.

Conflict of Interest statement. None declared.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [R01NS089622]. JKSD was supported from grant T32-NS082168.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Appel-Cresswell S., Vilarino-Guell C., Encarnacion M., Sherman H., Yu I., Shah B., Weir D., Thompson C., Szu-Tu C., Trinh J.. et al. (2013) Alpha-synuclein p.H50Q, a novel pathogenic mutation for Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord., 28, 811–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chartier-Harlin M.-C., Kachergus J., Roumier C., Mouroux V., Douay X., Lincoln S., Levecque C., Larvor L., Andrieux J., Hulihan M.. et al. (2004) Alpha-synuclein locus duplication as a cause of familial Parkinson’s disease. Lancet, 364, 1167–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kiely A.P., Asi Y.T., Kara E., Limousin P., Ling H., Lewis P., Proukakis C., Quinn N., Lees A.J., Hardy J.. et al. (2013) α-Synucleinopathy associated with G51D SNCA mutation: a link between Parkinson’s disease and multiple system atrophy? Acta Neuropathol., 125, 753–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Krüger R., Kuhn W., Müller T., Woitalla D., Graeber M., Kösel S., Przuntek H., Epplen J.T., Schöls L., Riess O. (1998) Ala30Pro mutation in the gene encoding alpha-synuclein in Parkinson‘s disease. Nat. Genet., 18, 106–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lesage S., Anheim M., Letournel F., Bousset L., Honoré A., Rozas N., Pieri L., Madiona K., Dürr A., Melki R.. et al. (2013) G51D α-synuclein mutation causes a novel parkinsonian-pyramidal syndrome. Ann. Neurol., 73, 459–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pasanen P., Myllykangas L., Siitonen M., Raunio A., Kaakkola S., Lyytinen J., Tienari P.J., Pöyhönen M., Paetau A. (2014) A novel α-synuclein mutation A53E associated with atypical multiple system atrophy and Parkinson’s disease-type pathology. Neurobiol. Aging, 35, 2180.e1–2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Polymeropoulos M.H., Lavedan C., Leroy E., Ide S.E., Dehejia A., Dutra A., Pike B., Root H., Rubenstein J., Boyer R.. et al. (1997) Mutation in the alpha-synuclein gene identified in families with Parkinson‘s disease. Science, 276, 2045–2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Proukakis C., Dudzik C.G., Brier T., MacKay D.S., Cooper J.M., Millhauser G.L., Houlden H., Schapira A.H. (2013) A novel α-synuclein missense mutation in Parkinson disease. Neurology, 80, 1062–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Singleton A.B., Farrer M., Johnson J., Singleton A., Hague S., Kachergus J., Hulihan M., Peuralinna T., Dutra A., Nussbaum R.. et al. (2003) Alpha-synuclein locus triplication causes Parkinson’s disease. Science, 302, 841.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zarranz J.J., Alegre J., Gómez-Esteban J.C., Lezcano E., Ros R., Ampuero I., Vidal L., Hoenicka J., Rodriguez O., Atarés B.. et al. (2004) The new mutation, E46K, of alpha-synuclein causes Parkinson and Lewy body dementia. Ann. Neurol., 55, 164–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Clayton D.F., George J.M. (1999) Synucleins in synaptic plasticity and neurodegenerative disorders. J. Neurosci. Res., 58, 120–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Davidson W.S., Jonas A., Clayton D.F., George J.M. (1998) Stabilization of alpha-synuclein secondary structure upon binding to synthetic membranes. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 9443–9449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Spillantini M.G., Schmidt M.L., Lee V.M., Trojanowski J.Q., Jakes R., Goedert M. (1997) Alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature, 388, 839–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Waxman E.A., Giasson B.I. (2009) Molecular mechanisms of alpha-synuclein neurodegeneration. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1792, 616–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goedert M., Spillantini M.G., Del Tredici K., Braak H. (2013) 100 years of Lewy pathology. Nat. Rev. Neurol., 9, 13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cookson M.R. (2005) The biochemistry of Parkinson‘s disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 74, 29–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hashimoto M., Masliah E. (1999) Alpha-synuclein in Lewy body disease and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Pathol., 9, 707–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lippa C.F., Fujiwara H., Mann D.M., Giasson B., Baba M., Schmidt M.L., Nee L.E., O’Connell B., Pollen D.A., St George-Hyslop P., et al. (1998) Lewy bodies contain altered alpha-synuclein in brains of many familial Alzheimer’s disease patients with mutations in presenilin and amyloid precursor protein genes. Am. J. Pathol., 153, 1365–1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Spillantini M.G., Crowther R.A., Jakes R., Cairns N.J., Lantos P.L., Goedert M. (1998) Filamentous alpha-synuclein inclusions link multiple system atrophy with Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurosci. Lett., 251, 205–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tu P.H., Galvin J.E., Baba M., Giasson B., Tomita T., Leight S., Nakajo S., Iwatsubo T., Trojanowski J.Q., Lee V.M. (1998) Glial cytoplasmic inclusions in white matter oligodendrocytes of multiple system atrophy brains contain insoluble alpha-synuclein. Ann. Neurol., 44, 415–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Conway K.A., Harper J.D., Lansbury P.T. (1998) Accelerated in vitro fibril formation by a mutant alpha-synuclein linked to early-onset Parkinson disease. Nat. Med., 4, 1318–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ghosh D., Mondal M., Mohite G.M., Singh P.K., Ranjan P., Anoop A., Ghosh S., Jha N.N., Kumar A., Maji S.K. (2013) The Parkinson’s disease-associated H50Q mutation accelerates α-synuclein aggregation in vitro. Biochemistry, 52, 6925–6927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Giasson B.I., Uryu K., Trojanowski J.Q., Lee V.M. (1999) Mutant and wild type human alpha-synucleins assemble into elongated filaments with distinct morphologies in vitro. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 7619–7622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li J., Uversky V.N., Fink A.L. (2001) Effect of familial Parkinson’s disease point mutations A30P and A53T on the structural properties, aggregation, and fibrillation of human alpha-synuclein. Biochemistry, 40, 11604–11613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Narhi L., Wood S.J., Steavenson S., Jiang Y., Wu G.M., Anafi D., Kaufman S.A., Martin F., Sitney K., Denis P.. et al. (1999) Both familial Parkinson‘s disease mutations accelerate alpha-synuclein aggregation. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 9843–9846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rutherford N.J., Moore B.D., Golde T.E., Giasson B.I. (2014) Divergent effects of the H50Q and G51D SNCA mutations on the aggregation of α-synuclein. J. Neurochem., 131, 859–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dhavale D.D., Tsai C., Bagchi D.P., Engel L.A., Sarezky J., Kotzbauer P.T. (2017) A sensitive assay reveals structural requirements for alpha-synuclein fibril growth. J. Biol. Chem., 292, 9034–9050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fares M.-B., Ait-Bouziad N., Dikiy I., Mbefo M.K., Jovičić A., Kiely A., Holton J.L., Lee S.-J., Gitler A.D., Eliezer D., et al. (2014) The novel Parkinson‘s disease linked mutation G51D attenuates in vitro aggregation and membrane binding of α-synuclein, and enhances its secretion and nuclear localization in cells. Hum. Mol. Genet., 23, 4491–4509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ghosh D., Sahay S., Ranjan P., Salot S., Mohite G.M., Singh P.K., Dwivedi S., Carvalho E., Banerjee R., Kumar A.. et al. (2014) The newly discovered Parkinson‘s disease associated Finnish mutation (A53E) attenuates α-synuclein aggregation and membrane binding. Biochemistry, 53, 6419–6421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rutherford N.J., Giasson B.I. (2015) The A53E α-synuclein pathological mutation demonstrates reduced aggregation propensity in vitro and in cell culture. Neurosci. Lett., 597, 43–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Choi W., Zibaee S., Jakes R., Serpell L.C., Davletov B., Crowther R.A., Goedert M. (2004) Mutation E46K increases phospholipid binding and assembly into filaments of human alpha-synuclein. FEBS Lett., 576, 363–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fredenburg R.A., Rospigliosi C., Meray R.K., Kessler J.C., Lashuel H.A., Eliezer D., Lansbury P.T. (2007) The impact of the E46K mutation on the properties of alpha-synuclein in its monomeric and oligomeric states. Biochemistry, 46, 7107–7118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Greenbaum E.A., Graves C.L., Mishizen-Eberz A.J., Lupoli M.A., Lynch D.R., Englander S.W., Axelsen P.H., Giasson B.I. (2005) The E46K mutation in alpha-synuclein increases amyloid fibril formation. J. Biol. Chem., 280, 7800–7807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ono K., Ikeda T., Takasaki J., Yamada M. (2011) Familial Parkinson disease mutations influence α-synuclein assembly. Neurobiol. Dis., 43, 715–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. El-Agnaf O.M., Jakes R., Curran M.D., Wallace A. (1998) Effects of the mutations Ala30 to Pro and Ala53 to Thr on the physical and morphological properties of alpha-synuclein protein implicated in Parkinson‘s disease. FEBS Lett., 440, 67–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kamiyoshihara T., Kojima M., Uéda K., Tashiro M., Shimotakahara S. (2007) Observation of multiple intermediates in alpha-synuclein fibril formation by singular value decomposition analysis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 355, 398–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Conway K.A., Lee S.J., Rochet J.C., Ding T.T., Williamson R.E., Lansbury P.T. Jr (2000) Acceleration of oligomerization, not fibrillization, is a shared property of both alpha-synuclein mutations linked to early-onset Parkinson‘s disease: implications for pathogenesis and therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 97, 571–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wood S.J., Wypych J., Steavenson S., Louis J.C., Citron M., Biere A.L. (1999) alpha-synuclein fibrillogenesis is nucleation-dependent. Implications for the pathogenesis of Parkinson‘s disease. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 19509–19512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Uchihara T., Giasson B.I. (2016) Propagation of alpha-synuclein pathology: hypotheses, discoveries, and yet unresolved questions from experimental and human brain studies. Acta Neuropathol., 131, 49–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Guo J.L., Lee V.M.Y. (2014) Cell-to-cell transmission of pathogenic proteins in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat. Med., 20, 130–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Goedert M., Clavaguera F., Tolnay M. (2010) The propagation of prion-like protein inclusions in neurodegenerative diseases. Trends Neurosci., 33, 317–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Goedert M., Masuda-Suzukake M., Falcon B. (2017) Like prions: the propagation of aggregated tau and α-synuclein in neurodegeneration. Brain, 140, 266–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Luk K.C., Kehm V.M., Zhang B., O’Brien P., Trojanowski J.Q., Lee V.M.Y. (2012) Intracerebral inoculation of pathological α-synuclein initiates a rapidly progressive neurodegenerative α-synucleinopathy in mice. J. Exp. Med., 209, 975–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rutherford N.J., Sacino A.N., Brooks M., Ceballos-Diaz C., Ladd T.B., Howard J.K., Golde T.E., Giasson B.I. (2015) Studies of lipopolysaccharide effects on the induction of α-synuclein pathology by exogenous fibrils in transgenic mice. Mol. Neurodegener., 10, 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sacino A.N., Brooks M., Thomas M.A., McKinney A.B., McGarvey N.H., Rutherford N.J., Ceballos-Diaz C., Robertson J., Golde T.E., Giasson B.I. (2014) Amyloidogenic α-synuclein seeds do not invariably induce rapid, widespread pathology in mice. Acta Neuropathol., 127, 645–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sacino A.N., Brooks M., Thomas M.A., McKinney A.B., Lee S., Regenhardt R.W., McGarvey N.H., Ayers J.I., Notterpek L., Borchelt D.R.. et al. (2014) Intramuscular injection of α-synuclein induces CNS α-synuclein pathology and a rapid-onset motor phenotype in transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 111, 10732–10737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Giasson B.I., Duda J.E., Quinn S.M., Zhang B., Trojanowski J.Q., Lee V.M.-Y. (2002) Neuronal alpha-synucleinopathy with severe movement disorder in mice expressing A53T human alpha-synuclein. Neuron, 34, 521–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rutherford N.J., Brooks M., Giasson B.I. (2016) Novel antibodies to phosphorylated α-synuclein serine 129 and NFL serine 473 demonstrate the close molecular homology of these epitopes. Acta Neuropathol. Commun., 4, 80.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ayers J.I., Brooks M.M., Rutherford N.J., Howard J.K., Sorrentino Z.A., Riffe C.J., Giasson B.I., Caughey B. (2017) Robust central nervous system pathology in transgenic mice following peripheral injection of α-synuclein fibrils. J. Virol., 91, e02095-16.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sorrentino Z.A., Brooks M.M.T., Hudson V., Rutherford N.J., Golde T.E., Giasson B.I., Chakrabarty P. (2017) Intrastriatal injection of α-synuclein can lead to widespread synucleinopathy independent of neuroanatomic connectivity. Mol. Neurodegener., 12, 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sacino A.N., Brooks M., McKinney A.B., Thomas M.A., Shaw G., Golde T.E., Giasson B.I. (2014) Brain injection of α-synuclein induces multiple proteinopathies, gliosis, and a neuronal injury marker. J. Neurosci., 34, 12368–12378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rospigliosi C.C., McClendon S., Schmid A.W., Ramlall T.F., Barré P., Lashuel H.A., Eliezer D. (2009) E46K Parkinson’s-linked mutation enhances C-terminal-to-N-terminal contacts in alpha-synuclein. J. Mol. Biol., 388, 1022–1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Brucale M., Sandal M., Di Maio S., Rampioni A., Tessari I., Tosatto L., Bisaglia M., Bubacco L., Samorì B. (2009) Pathogenic mutations shift the equilibria of alpha-synuclein single molecules towards structured conformers. Chembiochem, 10, 176–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. McKeith I.G., Dickson D.W., Lowe J., Emre M., O'Brien J.T., Feldman H., Cummings J., Duda J.E., Lippa C., Perry E.K.. et al. (2005) Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology, 65, 1863–1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Giasson B.I., Murray I.V., Trojanowski J.Q., Lee V.M. (2001) A hydrophobic stretch of 12 amino acid residues in the middle of alpha-synuclein is essential for filament assembly. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 2380–2386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Crystal A.S., Giasson B.I., Crowe A., Kung M.-P., Zhuang Z.-P., Trojanowski J.Q., Lee V.M.-Y. (2003) A comparison of amyloid fibrillogenesis using the novel fluorescent compound K114. J. Neurochem, 86, 1359–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Giasson B.I., Jakes R., Goedert M., Duda J.E., Leight S., Trojanowski J.Q., Lee V.M. (2000) A panel of epitope-specific antibodies detects protein domains distributed throughout human alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies of Parkinson‘s disease. J. Neurosci. Res., 59, 528–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Waxman E.A., Duda J.E., Giasson B.I. (2008) Characterization of antibodies that selectively detect alpha-synuclein in pathological inclusions. Acta Neuropathol., 116, 37–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Duda J.E., Giasson B.I., Mabon M.E., Lee V.M.-Y., Trojanowski J.Q. (2002) Novel antibodies to synuclein show abundant striatal pathology in Lewy body diseases. Ann. Neurol., 52, 205–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.