Abstract

Autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and coeliac disease are typical examples of complex genetic diseases caused by a combination of genetic and non-genetic risk factors. Insight into the genetic risk factors (single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)) has increased since genome-wide association studies (GWAS) became possible in 2007 and, for individual diseases, SNPs can now explain some 15–50% of genetic risk. GWAS have also shown that some 50% of the genetic risk factors for individual autoimmune diseases overlap between different diseases. Thus, shared risk factors may converge to pathways that, when perturbed by genetic variation, predispose to autoimmunity in general. This raises the question of what determines disease specificity, and suggests that identical risk factors may have different effects in various autoimmune diseases. Addressing this question requires translation of genetic risk factors to causal genes and then to molecular and cellular pathways. Since >90% of the genetic risk factors are found in the non-coding part of the genome (i.e. outside the exons of protein-coding genes) and can have an impact on gene regulation, there is an urgent need to better understand the non-coding part of the genome. Here, we will outline the methods being used to unravel the gene regulatory networks perturbed in autoimmune diseases and the importance of doing this in the relevant cell types. We will highlight findings in coeliac disease, which manifests in the small intestine, to demonstrate how cell type and disease context can impact on the consequences of genetic risk factors.

Context Specificity of Gene Regulation

Transcription regulation is a complex system which includes enhancers and promoters, transcription factors and their binding sites, and regulatory RNAs such as long non-coding RNAs, that all act in highly cell type-specific manners to achieve appropriate levels of gene expression. To further our understanding of the non-coding genome, there is a range of different techniques needed to comprehensively investigate the regulatory elements, each with its own challenges and limitations (Box 1). Many large consortia, such as ENCODE (1), Epigenome Roadmap (2), Blueprint (3) and FANTOM (4), have used these techniques to systematically document the individual elements including enhancers and non-coding RNAs, in more than 100 different cell types and even under different conditions. These initiatives have moved the field of transcription regulation forward considerably, but have also clearly shown that especially enhancers and non-coding RNAs are extremely cell type- and condition-specific (2,5,6) (Fig. 1). For example, AP001057.1 is a long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) gene that is exclusively expressed in monocytes and upregulated upon induction with microbial agents. This lncRNA is located in a locus associated with coeliac disease and Crohn’s disease (5). Naturally, since the non-coding genome is cell type- and condition-specific manner, so too is the disruption of the non-coding genome by genetic variants associated with diseases.

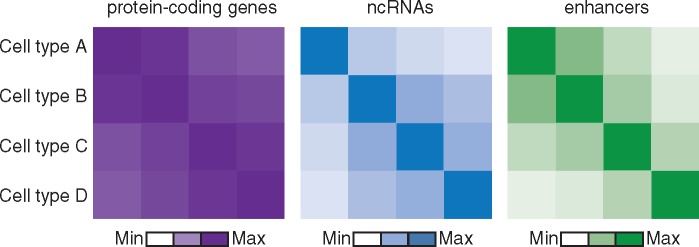

Figure 1.

LncRNAs and enhancers are more cell-type-specific than protein-coding gene expression. Schematic representation of the correlation between the activities of protein-coding genes (purple), non-coding RNAs (blue) and enhancers (green).

An important step in understanding the role of the non-coding genome in disease is to link disease-specific risk single nucleotide polymorphism (SNPs) to their target genes. This can be done in two ways: firstly, by identifying causal SNPs in non-coding regions and linking their function to causal genes, and secondly, by correlating gene expression with genotype. In many ways, the first approach is more informative, as the molecular mechanism for the causative effect on gene expression will be identified. However, identifying the true causal SNPs predisposing to disease is highly complicated because of the presence of linkage disequilibrium (LD) (7), the phenomenon that multiple genetic variants close to each other are co-inherited together and therefore cannot be distinguished. But even within a long stretch of correlated SNPs, their evidence for being causal increases when they overlap enhancers (8–10), when they disrupt predicted motifs including transcription factor binding sites (11–13), and/or when they overlap evolutionary conserved regions (14).

Alternatively, a powerful tool used in the second approach is cis-eQTL (expression quantitative trait loci) analysis, i.e. identifying genes whose level of expression is correlated with a close-by SNP. One example that shows the power of eQTL analysis is the obesity-associated SNP, rs1421085, that is located in one of the introns of the FTO gene. As there was no SNP that disrupted a protein-coding sequence, FTO was considered to be an excellent positional candidate gene. Many follow-up and functional studies have been conducted on FTO and led to more than 1,000 scientific articles, until Claussnitzer et al. discovered that rs1421085 affects the expression of IRX3, a transcription factor important for neuronal development, in brain tissue. Functional follow-up of IRX3 offers convincing evidence for this gene playing a role in obesity (15).

Examples of both approaches and the insights they have yielded on the role of genetics in autoimmune diseases are described later in this review.

Genetic Variants Associated with Autoimmune Disease Are Enriched in Regulatory Elements

Intersecting disease-associated SNPs with data on regulatory elements can be used to pinpoint causal variants among a set of SNPs in high LD. Autoimmune diseases have been prime examples for conducting such studies, as there are ample data on different immune cell types (1–4). Performing such an analysis on SNPs associated with coeliac disease showed significant enrichment in B-cell-specific enhancers (16). These results have not only helped to define potentially causal SNPs, but also imply an important role for B-cells in a disease that is traditionally regarded as a T-cell disorder. Trynka et al. (17) showed that active non-coding regions in CD4+ regulatory T-cells overlapped with 31 SNPs associated with rheumatoid arthritis, implying a prominent role for these cells in its aetiology. The Epigenome Roadmap consortium, which has annotated regulatory elements based on epigenetic marks in 111 different primary tissues and cell types, both under resting and stimulated conditions, has allowed a systematic enrichment analysis to be performed (8). Indeed, all autoimmune diseases display enrichment of SNPs in non-coding regions of different subsets of immune cells. Moreover, SNPs associated with type 1 diabetes overlap regulatory elements in pancreatic islets, while SNPs for Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are enriched in regulatory elements in the colonic mucosa (8), indicating that cell types other than immune cells are also important in autoimmune diseases.

While enrichment analysis helps to prioritize potentially causal SNPs, it does not prove their causality. The most likely mechanism by which causal SNPs act is by disruption of transcription factor binding sites (11,13,15,18–20). For example, SNPs associated with coeliac disease and rheumatoid arthritis disrupt binding sites of T-BET (19), IRF1 (20), AP-1 (8) and of transcription factors that interact with IRF9 (11). Surprisingly, only 1–20%, depending on the transcription factor, of the SNPs that disrupt a transcription factor binding site in a regulatory region also lead to changed activity of the regulatory element, either in a constitutive or cell-type-specific manner (15); this is based on measuring allelic imbalance between the two different haplotypes (Fig. 2). Large-scale massive parallel reporter assays of eQTL-SNPs have identified SNPs that affect the activity of regulatory elements in lymphoblastoid cell lines (21), including rs9283753, an SNP associated with ankylosing spondylitis that overlaps a distal enhancer of the prostaglandin E receptor 4 gene (PTGER4). Still, less than 3% of all the SNPs tested changed regulatory activity (21). Overall, causal SNPs have not been identified for the vast majority of genetic loci associated with autoimmune diseases, which may be due to the fact that most epigenetic annotations are derived from cells under resting conditions whereas autoimmune disease SNPs that are prioritized to be causal seem to be enriched, mainly in stimulated cell types (8).

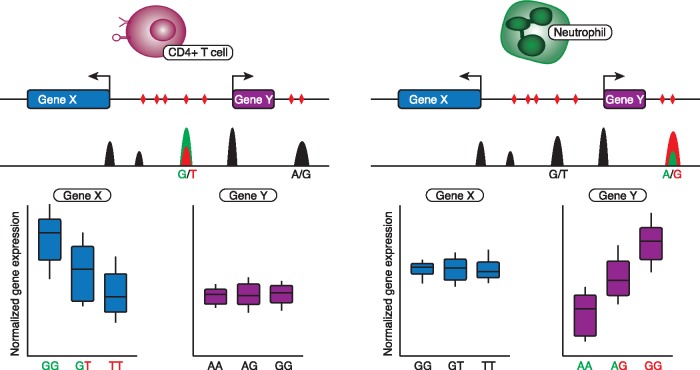

Figure 2.

eQTLs can be cell-type-specific. Schematic representation of a genetic risk locus with variable effects on gene expression in cis, depending on cell type. From top to bottom: the cell type, the gene annotation track with SNPs (in red triangles), a cell-type-specific DHS-seq track displaying open chromatin regions (in black) and causal mutations and allele-specific open chromatin (in green and red); and the eQTL effects of causal mutations in each cell type. Left: gene X displays an eQTL effect in CD4+ T cells caused by a G-to-T mutation in an active enhancer. Right: in neutrophils, gene X is not differentially regulated by the G-to-T mutation, but gene Y is affected by an A-to-G mutation in the same locus.

Finally, identification of causal SNPs is not enough to infer downstream effects of the SNPs active in disease. Therefore, causal SNPs and the non-coding regions they disrupt have to be linked to the affected genes. The most elegant way to do so is by mapping the looping interactions between non-coding regions and the genes they regulate by using chromatin capture techniques such as 4 C, promoter capture HiC and ChIA-PET (Box 1) (10,11,15,22,23). This has prioritized multiple genes over long distances from the GWAS SNPs, including genes that are outside the typical cis-window of 500 kb-1 Mb (Megabase) used in cis-eQTL analysis. For example, FOXO1 has an interaction with a non-coding region that overlaps a rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile idiopathic arthritis SNP over 1 Mb away (22). However, 3D interaction data are not commonly generated, making it difficult to detect the loop between causal SNPs and genes. The Blueprint consortium (3) has started to close this gap and analysed promoter capture HiC for 17 primary immune cell types (24), thereby prioritizing 421 genes for autoimmune diseases based on GWAS summary statistics and 3D interaction data.

Thus, with increasing understanding of how the non-coding genome regulates gene expression in relevant cell types, it will be feasible to fine map and understand the mechanisms of causal SNPs in autoimmune disease.

SNPs Have Variable Effects Based on Cell Type and Context

Fine mapping and functionally linking causal SNPs to affected genes reveals a great deal about the molecular mechanisms by which SNPs affect autoimmune diseases, but does not allow for high-throughput detection of causal genes. So eQTL analysis is more commonly used as a direct way of detecting the effects of genetic variation on gene expression (Fig. 2).

Most large eQTL studies to date have used peripheral blood expression data (10,16,25–30) and approximately 42% of SNPs associated with autoimmune diseases can be linked to a nearby gene by using gene expression data from peripheral blood (10). These eQTL studies showed that disease SNPs can also affect the expression of long non-coding RNAs (10,31), suggesting that risk SNPs may interfere with transcription regulation through regulatory RNAs. Although peripheral blood is likely to be appropriate for many of the SNPs associated with autoimmunity, risk SNPs for other diseases may fail to show an effect in blood and need to be investigated in other cell types. Moreover, how eQTL genes exert an effect in disease aetiology is difficult to interpret without knowing the cell type in which the gene is de-regulated due to genetic variants. Several strategies have been applied to circumvent these issues.

First, statistical methods can be applied to reassign eQTL signals to specific cell types or conditions in heterogeneous samples including peripheral blood (29,32,33). The largest eQTL study to date classified 12% of over 23,000 eQTLs as cell-type-specific (29). But a limitation is that these methods may not be able to capture a specific context including exposure to an antigen, or a rare cell type.

Alternatively, eQTL analysis can be performed in specific tissues, for example as done by the GTeX consortium and others (34–36) or by sorting whole blood into its major cell types (12,18,20,37–43). These approaches are much more expensive to perform and these eQTL studies are thus done on smaller cohorts and have reduced power. Nonetheless, many unique eQTLs have been identified by studies on specific cell types (Figs 2 and 3). For example, a neutrophil-specific change in the gene expression of protein-arginine deiminase type IV (PADI-4) due to the rheumatoid arthritis-associated SNP rs2240335 only overlaps with H3K27Ac marks in neutrophils, but not in monocytes and a further 450 out of 3281 neutrophil cis-eQTLs were not observed in non-neutrophil myeloid or lymphoid cell lineages (18). Comparison of the highly related CD4+ and CD8+ T cells also identified interleukin 27 as a protective eQTL gene for type 1 diabetes exclusively in CD4+ T cells (40).

Not only the specific cell type may be important in identifying eQTLs, the context in which the cells operate is also relevant for autoimmune diseases, since these require interaction with auto-antigens for the disease to manifest (Fig. 3). Multiple studies have identified eQTLs that are not detected under resting conditions, but which appear strongly after stimulation (20,38,41,44). This also depends on the stimulant and the time of stimulation, as Fairfax et al. have shown by stimulating monocytes with LPS for 2 hours and with LPS or interferon γ (IFNγ) for 24 hours (38). Some genes even show opposing eQTL effects between stimulated and resting conditions (for example, HIP1, STEAP4 and CEACAM3), or between different stimulants (CEACAM3), demonstrating how complex the contribution of SNPs to disease can be. So detecting cell-type- and condition-specific eQTLs increases detection of eQTLs in general and offers better interpretation of the role of the eQTL genes in disease aetiology.

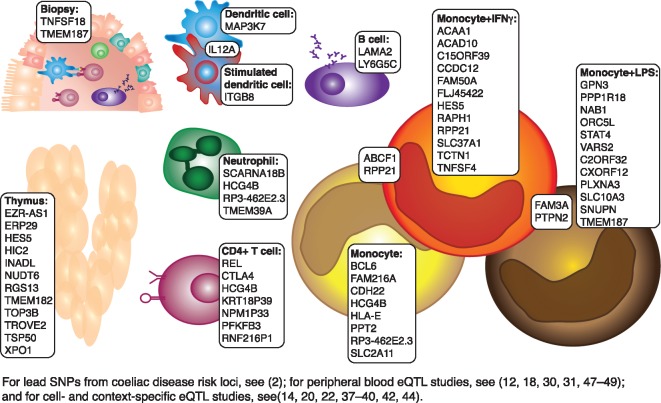

Figure 3.

Cell-type- and context-specific eQTLs for coeliac disease. All lead SNPs from coeliac disease risk loci and proxy-SNPs in LD (r2>0.8) were compared to peripheral blood eQTL studies and cell- and context-specific eQTL studies. eQTLs unique for these studies are shown along with the cell type and context in which they were identified.

Context-Specific Understanding of Autoimmune-Associated SNPs Important

To demonstrate how context- and cell-type-specific eQTL analysis can contribute to understanding autoimmune diseases, we have taken coeliac disease as an example. We extracted all the eQTL genes identified in a cell-type-specific context (12,18,20,35–38,40,42), but not in peripheral blood (10,16,28,45–47) (Fig. 3). Many of these genes have functions that are highly relevant for coeliac disease. For example, REL, encoding an Nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) subunit, is an eQTL in CD4+ T cells, the cell type that recognizes and responds to the gluten peptides that trigger coeliac disease and set in motion a chain of events leading to inflammation and an autoimmune response in the small intestines (9,48). A major signalling pathway that regulates this response is NF-κB pathway (49), so any changes in levels of NF-κB subunits in CD4+ T cells can have profound effects on the severity of the response to gluten peptides. Another example is protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor type 2 (PTPN2), which shows an eQTL effect in stimulated monocytes only (Fig. 3). PTPN2 encodes a phosphatase involved in the monocyte response to IFNγ in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and rheumatoid arthritis (50–52), thus a similar role in coeliac disease is possible since IFNγ is a major coeliac disease-associated cytokine (9,48,53). To conclude, many genetic variants may have effects in a cell-type-specific manner, and detection of these effects can provide direct insights into disease mechanisms.

While these eQTLs have allowed us to prioritize the genes and pathways that are pivotal to disease aetiology, it is still unclear whether these genes are truly causal. Statistical tools that make use of the relationship between GWAS summary statistics and eQTL-SNP pairs to distinguish which eQTLs best explain the genetic effect on disease, have only been moderately successful (54–57) and the lack of cell–type- and condition-specific eQTL data were given as one of the possible reasons for this (56).

Therefore, it is critical to understand the conditions and circumstances in which autoimmune diseases occur. However, unlike coeliac disease, these circumstances are unknown for most autoimmune diseases and for coeliac disease many questions remain as well. Even though gluten peptides have been identified as the direct trigger of coeliac disease, the full context in which mucosal inflammation takes place is highly complex. Many cytokines including IFNγ, IL15 and IL21 play an important role (9,48,53) and recently, Bouziat et al have shown that specific strains of Reovirus can invoke tolerance to gluten in mice, suggesting that virus infections can trigger coeliac disease (58). Moreover, commensal gut microbes have also been implicated in coeliac disease (59). Consequently, even for coeliac disease, it is nearly impossible to emulate the context in which genetic variants exert an effect on gene expression.

However, different stimuli have different effects on gene expression and the role of genetic variation might be specific to each separate stimulus. Comparative expression analysis of different pathogens has shown pathogen-specific gene expression changes in immune cells (20,60) and production of variable levels of cytokines (61–63). Moreover, cytokine production is influenced by genetic variants in a pathogen-specific manner (61, 63). So to truly capture the effects of genetic variation involved in autoimmune diseases, it may be necessary to analyse patient material as all the patient’s conditions will be conducive to the pathology.

Concluding Remarks

Since the association of genetic loci with autoimmune diseases, many eQTL and fine-mapping studies have been performed and made great strides in identifying putative causal genes and pathways affected by genetic variation associated with disease. However, the consequences of genetic variants may depend greatly on the cell type and conditions in which they are measured. As disease-specific cell types and conditions are often poorly defined in autoimmune disease, detection of eQTLs in patient-derived material may be the most straightforward way (35,36). Unfortunately, the availability of material from sufficient numbers of patients and the amount of material itself are often limiting factors, making analysis of these samples difficult. However, sequencing techniques have improved over the years, making single-cell transcriptome and single-cell epigenome sequencing possible (Box 1). Moreover, statistical deconvolution of eQTL effects in solid tissues into single cell types is becoming increasingly sensitive (33,64). Thus, with the use of statistical approaches and sophisticated techniques that require minimum amounts of input material, we can begin to discover the cell- and context-specific role of genetic variation in autoimmune disease.

Acknowledgements

I.H.J. is supported by a Rosalind Franklin Fellowship from the University of Groningen and a VIDI from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (016.Vidi.171.047). C.W. is supported by FP7/2007-2013/ERC Advanced Grant (agreement 2012-322698), Stiftelsen Kristian Gerhard Jebsen, and a Spinoza Prize from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO SPI 92-266).

Conflict of Interest statement. None declared.

Funding

University of Groningen and a VIDI from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (016.Vidi.171.047). FP7/2007-2013/ERC Advanced Grant (agreement 2012-322698) and Stiftelsen Kristian Gerhard Jebsen, and a Spinoza Prize from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO SPI 92-266) and Rosalind Franklin Fellowship awarded by the University of Groningen (I.H.J). Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by the FP7/2007-2013/ERC Advanced Grant (agreement 2012-322698).

References

- 1. ENCODE Project Consortium, T.E.P. (2012) An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature, 489, 57–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kundaje A., Meuleman W., Ernst J., Bilenky M., Yen A., Heravi-Moussavi A., Kheradpour P., Zhang Z., Wang J., Ziller M.J.. et al. (2015) Integrative analysis of 111 reference human epigenomes. Nature, 518, 317–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stunnenberg H.G., Hirst M., Abrignani S., Adams D., de Almeida M., Altucci L., Amin V., Amit I., Antonarakis S.E., Aparicio S.. et al. (2016) The International Human Epigenome Consortium: A Blueprint for Scientific Collaboration and Discovery. Cell, 167, 1145–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. FANTOM Consortium and the RIKEN PMI and CLST (DGT), T.F.C. and the R.P. and C. Forrest A.R.R., Kawaji H., Rehli M., Baillie J.K., de Hoon M.J.L., Haberle V., Lassmann T., Kulakovskiy I.V., Lizio M.. et al. (2014) A promoter-level mammalian expression atlas. Nature, 507, 462–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hon C.-C., Ramilowski J.A., Harshbarger J., Bertin N., Rackham O.J.L., Gough J., Denisenko E., Schmeier S., Poulsen T.M., Severin J.. et al. (2017) An atlas of human long non-coding RNAs with accurate 5′ ends. Nature, 543, 199–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Amin V., Harris R.A., Onuchic V., Jackson A.R., Charnecki T., Paithankar S., Lakshmi Subramanian S., Riehle K., Coarfa C., Milosavljevic A. (2015) Epigenomic footprints across 111 reference epigenomes reveal tissue-specific epigenetic regulation of lincRNAs. Nat. Commun., 6, 6370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ardlie K.G., Kruglyak L., Seielstad M. (2002) Patterns of linkage disequilibrium in the human genome. Nat. Rev. Genet., 3, 299–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Farh K.K., Marson A., Zhu J., Kleinewietfeld M., Housley W.J., Beik S., Shoresh N., Whitton H., Ryan R.J., Shishkin A.A.. et al. (2014) Genetic and epigenetic fine mapping of causal autoimmune disease variants. Nature, 10.1038/nature13835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Withoff S., Li Y., Jonkers I., Wijmenga C. (2016) Understanding celiac disease by genomics. Trends Genet., 32, 295–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ricaño-Ponce I., Zhernakova D.V., Deelen P., Luo O., Li X., Isaacs A., Karjalainen J., Di Tommaso J., Borek Z.A., Zorro M.M.. et al. (2016) Refined mapping of autoimmune disease associated genetic variants with gene expression suggests an important role for non-coding RNAs. J. Autoimmun., 10.1016/j.jaut.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Maurano M.T., Humbert R., Rynes E., Thurman R.E., Haugen E., Wang H., Reynolds A.P., Sandstrom R., Qu H., Brody I.. et al. (2012) Systematic localization of common disease-associated variation in regulatory DNA. Science, 337, 1190–1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen L., Ge B., Casale F.P., Vasquez L., Kwan T., Garrido-Martín D., Watt S., Yan Y., Kundu K., Ecker S.. et al. (2016) Genetic drivers of epigenetic and transcriptional variation in human immune cells. Cell, 167, 1398–1414.e24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Maurano M.T., Haugen E., Sandstrom R., Vierstra J., Shafer A., Kaul R., Stamatoyannopoulos J.A. (2015) Large-scale identification of sequence variants influencing human transcription factor occupancy in vivo. Nat. Genet., 47, 1393–1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cheng Y., Ma Z., Kim B.-H.H., Wu W., Cayting P., Boyle A.P., Sundaram V., Xing X., Dogan N., Li J.. et al. (2014) Principles of regulatory information conservation between mouse and human. Nature, 515, 371–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Claussnitzer M., Dankel S.N., Kim K.-H., Quon G., Meuleman W., Haugen C., Glunk V., Sousa I.S., Beaudry J.L., Puviindran V.. et al. (2015) FTO obesity variant circuitry and adipocyte browning in humans. N. Engl. J. Med., 10.1056/NEJMoa1502214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kumar V., Gutierrez-Achury J., Kanduri K., Almeida R., Hrdlickova B., Zhernakova D.V., Westra H.-J.J., Karjalainen J., Ricaño-Ponce I., Li Y.. et al. (2014) Systematic annotation of celiac disease loci refines pathological pathways and suggests a genetic explanation for increased interferon gamma levels. Hum. Mol. Genet., 10.1093/hmg/ddu453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Trynka G., Sandor C., Han B., Xu H., Stranger B.E., Liu X.S., Raychaudhuri S. (2012) Chromatin marks identify critical cell types for fine mapping complex trait variants. Nat. Genet., 45, 124–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Naranbhai V., Fairfax B.P., Makino S., Humburg P., Wong D., Ng E., Hill A.V.S., Knight J.C. (2015) Genomic modulators of gene expression in human neutrophils. Nat. Commun., 6, 7545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Soderquest K., Hertweck A., Giambartolomei C., Henderson S., Mohamed R., Goldberg R., Perucha E., Franke L., Herrero J., Plagnol V.. et al. (2017) Genetic variants alter T-bet binding and gene expression in mucosal inflammatory disease. PLOS Genet., 13, e1006587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee M.N., Ye C., Villani A.-C., Raj T., Li W., Eisenhaure T.M., Imboywa S.H., Chipendo P.I., Ran F.A., Slowikowski K.. et al. (2014) Common genetic variants modulate pathogen-sensing responses in human dendritic cells. Science, 343, 1246980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tewhey R., Kotliar D., Park D.S., Liu B., Winnicki S., Reilly S.K., Andersen K.G., Mikkelsen T.S., Lander E.S., Schaffner S.F.. et al. (2016) Direct identification of hundreds of expression-modulating variants using a multiplexed reporter assay. Cell, 165, 1519–1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Martin P., McGovern A., Orozco G., Duffus K., Yarwood A., Schoenfelder S., Cooper N.J., Barton A., Wallace C., Fraser P.. et al. (2015) Capture Hi-C reveals novel candidate genes and complex long-range interactions with related autoimmune risk loci. Nat. Commun., 6, 10069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Corradin O., Cohen A.J., Luppino J.M., Bayles I.M., Schumacher F.R., Scacheri P.C. (2016) Modeling disease risk through analysis of physical interactions between genetic variants within chromatin regulatory circuitry. Nat. Genet., 10.1038/ng.3674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Javierre B.M., Burren O.S., Wilder S.P., Kreuzhuber R., Hill S.M., Sewitz S., Cairns J., Wingett S.W., Várnai C., Thiecke M.J.. et al. (2016) Lineage-specific genome architecture links enhancers and non-coding disease variants to target gene promoters. Cell, 167, 1369–1384.e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lappalainen T., Sammeth M., Friedländer M.R., ‘t Hoen P.A.C., Monlong J., Rivas M.A., Gonzàlez-Porta M., Kurbatova N., Griebel T., Ferreira P.G.. et al. (2013) Transcriptome and genome sequencing uncovers functional variation in humans. Nature, 501, 506–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mehta D., Heim K., Herder C., Carstensen M., Eckstein G., Schurmann C., Homuth G., Nauck M., Völker U., Roden M.. et al. (2013) Impact of common regulatory single-nucleotide variants on gene expression profiles in whole blood. Eur. J. Hum. Genet., 21, 48–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schramm K., Marzi C., Schurmann C., Carstensen M., Reinmaa E., Biffar R., Eckstein G., Gieger C., Grabe H.-J., Homuth G.. et al. (2014) Mapping the genetic architecture of gene regulation in whole blood. PLoS One, 9, e93844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Westra H.-J., Peters M.J., Esko T., Yaghootkar H., Schurmann C., Kettunen J., Christiansen M.W., Fairfax B.P., Schramm K., Powell J.E.. et al. (2013) Systematic identification of trans eQTLs as putative drivers of known disease associations. Nat. Genet., 45, 1238–1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhernakova D.V., Deelen P., Vermaat M., van Iterson M., van Galen M., Arindrarto W., van ’t Hof P., Mei H., van Dijk F., Westra H.-J.. et al. (2016) Identification of context-dependent expression quantitative trait loci in whole blood. Nat. Genet., 49, 139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wright F.A., Sullivan P.F., Brooks A.I., Zou F., Sun W., Xia K., Madar V., Jansen R., Chung W., Zhou Y.-H.. et al. (2014) Heritability and genomics of gene expression in peripheral blood. Nat. Genet., 46, 430–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kumar V., Westra H.-J.J., Karjalainen J., Zhernakova D.V., Esko T., Hrdlickova B., Almeida R., Zhernakova A., Reinmaa E., Võsa U.. et al. (2013) Human disease-associated genetic variation impacts large intergenic non-coding RNA expression. PLoS Genet., 9, e1003201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Westra H.-J., Arends D., Esko T., Peters M.J., Schurmann C., Schramm K., Kettunen J., Yaghootkar H., Fairfax B.P., Andiappan A.K.. et al. (2015) Cell specific eQTL analysis without sorting cells. PLoS Genet., 11, e1005223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shen-Orr S.S., Gaujoux R. (2013) Computational deconvolution: extracting cell type-specific information from heterogeneous samples. Curr. Opin. Immunol., 25, 571–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Melé M., Ferreira P.G., Reverter F., DeLuca D.S., Monlong J., Sammeth M., Young T.R., Goldmann J.M., Pervouchine D.D., Sullivan T.J.. et al. (2015) The human transcriptome across tissues and individuals. Science, 10.1126/science.aaa0355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Amundsen S.S., Viken M.K., Sollid L.M., Lie B.A. (2014) Coeliac disease-associated polymorphisms influence thymic gene expression. Genes Immun, 10.1038/gene.2014.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Plaza-Izurieta L., Fernandez-Jimenez N., Irastorza I., Jauregi-Miguel A., Romero-Garmendia I., Vitoria J.C., Bilbao J.R. (2014) Expression analysis in intestinal mucosa reveals complex relations among genes under the association peaks in celiac disease. Eur. J. Hum. Genet., 23, 1100–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Raj T., Rothamel K., Mostafavi S., Ye C., Lee M.N., Replogle J.M., Feng T., Lee M., Asinovski N., Frohlich I.. et al. (2014) Polarization of the effects of autoimmune and neurodegenerative risk alleles in leukocytes. Science, 344, 519–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fairfax B.P., Humburg P., Makino S., Naranbhai V., Wong D., Lau E., Jostins L., Plant K., Andrews R., McGee C.. et al. (2014) Innate immune activity conditions the effect of regulatory variants upon monocyte gene expression. Science, 343, 1246949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ferraro A., D’Alise A.M., Raj T., Asinovski N., Phillips R., Ergun A., Replogle J.M., Bernier A., Laffel L., Stranger B.E.. et al. (2014) Interindividual variation in human t regulatory cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A, 111, E1111–E1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kasela S., Kisand K., Tserel L., Kaleviste E., Remm A., Fischer K., Esko T., Westra H.-J., Fairfax B.P., Makino S.. et al. (2017) Pathogenic implications for autoimmune mechanisms derived by comparative eQTL analysis of CD4+ versus CD8+ T cells. PLOS Genet., 13, e1006643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kim S., Becker J., Bechheim M., Kaiser V., Noursadeghi M., Fricker N., Beier E., Klaschik S., Boor P., Hess T.. et al. (2014) Characterizing the genetic basis of innate immune response in TLR4-activated human monocytes. Nat. Commun., 5, 5236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fairfax B.P., Makino S., Radhakrishnan J., Plant K., Leslie S., Dilthey A., Ellis P., Langford C., Vannberg F.O., Knight J.C. (2012) Genetics of gene expression in primary immune cells identifies cell type–specific master regulators and roles of HLA alleles. Nat. Genet., 44, 502–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Andiappan A.K., Melchiotti R., Poh T.Y., Nah M., Puan K.J., Vigano E., Haase D., Yusof N., San Luis B., Lum J.. et al. (2015) Genome-wide analysis of the genetic regulation of gene expression in human neutrophils. Nat. Commun., 6, 7971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Barreiro L.B., Tailleux L., Pai A.A., Gicquel B., Marioni J.C., Gilad Y. (2012) Deciphering the genetic architecture of variation in the immune response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A, 109, 1204–1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Deelen P., Zhernakova D.V., de Haan M., van der Sijde M., Bonder M.J., Karjalainen J., van der Velde K.J., Abbott K.M., Fu J., Wijmenga C.. et al. (2015) Calling genotypes from public RNA-sequencing data enables identification of genetic variants that affect gene-expression levels. Genome Med., 7, 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhernakova D.V., de Klerk E., Westra H.-J., Mastrokolias A., Amini S., Ariyurek Y., Jansen R., Penninx B.W., Hottenga J.J., Willemsen G.. et al. (2013) DeepSAGE reveals genetic variants associated with alternative polyadenylation and expression of coding and non-coding transcripts. PLoS Genet., 9, e1003594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dubois P.C.A., Trynka G., Franke L., Hunt K.A., Romanos J., Curtotti A., Zhernakova A., Heap G.A.R., Adány R., Aromaa A.. et al. (2010) Multiple common variants for celiac disease influencing immune gene expression. Nat. Genet., 42, 295–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sollid L.M., Jabri B. (2013) Triggers and drivers of autoimmunity: lessons from coeliac disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol., 10.1038/nri3407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Oh H., Ghosh S. (2013) NF-κB: roles and regulation in different CD4(+) T-cell subsets. Immunol. Rev., 252, 41–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Scharl M., Mwinyi J., Fischbeck A., Leucht K., Eloranta J.J., Arikkat J., Pesch T., Kellermeier S., Mair A., Kullak-Ublick G.A.. et al. (2012) Crohn’s disease-associated polymorphism within the PTPN2 gene affects muramyl-dipeptide-induced cytokine secretion and autophagy. Inflamm. Bowel Dis., 18, 900–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Morón B., Spalinger M., Kasper S., Atrott K., Frey-Wagner I., Fried M., McCole D.F., Rogler G., Scharl M. (2013) Activation of protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor Type 2 by spermidine exerts anti-inflammatory effects in human THP-1 monocytes and in a mouse model of acute colitis. PLoS One, 8, e73703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Scharl M., Hruz P., McCole D.F. (2010) Protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor type 2 regulates IFN-γ-induced cytokine signaling in THP-1 monocytes. Inflamm. Bowel Dis., 16, 2055–2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. van Bergen J., Mulder C.J., Mearin M.L., Koning F. (2015) Local communication among mucosal immune cells in patients with celiac disease. Gastroenterology, 148, 1187–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Guo H., Fortune M.D., Burren O.S., Schofield E., Todd J.A., Wallace C. (2015) Integration of disease association and eQTL data using a Bayesian colocalisation approach highlights six candidate causal genes in immune-mediated diseases. Hum. Mol. Genet., 24, 3305–3313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zhu Z., Zhang F., Hu H., Bakshi A., Robinson M.R., Powell J.E., Montgomery G.W., Goddard M.E., Wray N.R., Visscher P.M.. et al. (2016) Integration of summary data from GWAS and eQTL studies predicts complex trait gene targets. Nat. Genet., 48, 481–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Chun S., Casparino A., Patsopoulos N.A., Croteau-Chonka D.C., Raby B.A., De Jager P.L., Sunyaev S.R., Cotsapas C. (2017) Limited statistical evidence for shared genetic effects of eQTLs and autoimmune-disease-associated loci in three major immune-cell types. Nat. Genet., 49, 600–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Giambartolomei C., Vukcevic D., Schadt E.E., Franke L., Hingorani A.D., Wallace C., Plagnol V. (2014) Bayesian test for colocalisation between pairs of genetic association studies using summary statistics. PLoS Genet., 10, e1004383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bouziat R., Hinterleitner R., Brown J.J., Stencel-Baerenwald J.E., Ikizler M., Mayassi T., Meisel M., Kim S.M., Discepolo V., Pruijssers A.J.. et al. (2017) Reovirus infection triggers inflammatory responses to dietary antigens and development of celiac disease. Science, 356, 44–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Cenit M., Olivares M., Codoñer-Franch P., Sanz Y. (2015) Intestinal microbiota and celiac disease: cause, consequence or co-evolution? Nutrients, 7, 6900–6923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Smeekens S.P., Ng A., Kumar V., Johnson M.D., Plantinga T.S., van Diemen C., Arts P., Verwiel E.T.P., Gresnigt M.S., Fransen K.. et al. (2013) Functional genomics identifies type I interferon pathway as central for host defense against Candida albicans. Nat. Commun., 4, 1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Li Y., Oosting M., Deelen P., Ricaño-Ponce I., Smeekens S., Jaeger M., Matzaraki V., Swertz M.A., Xavier R.J., Franke L.. et al. (2016) Inter-individual variability and genetic influences on cytokine responses to bacteria and fungi. Nat. Med., 22, 952–960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Schirmer M., Smeekens S.P., Vlamakis H., Jaeger M., Oosting M., Franzosa E.A., Jansen T., Jacobs L., Bonder M.J., Kurilshikov A.. et al. (2016) Linking the human gut microbiome to inflammatory cytokine production capacity. Cell, 167, 1125–1136.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Li Y., Oosting M., Smeekens S.P., Jaeger M., Aguirre-Gamboa R., Le K.T.T., Deelen P., Ricaño-Ponce I., Schoffelen T., Jansen A.F.M.. et al. (2016) A functional genomics approach to understand variation in cytokine production in humans. Cell, 167, 1099–1110.e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Shen-Orr S.S., Tibshirani R., Khatri P., Bodian D.L., Staedtler F., Perry N.M., Hastie T., Sarwal M.M., Davis M.M., Butte A.J. (2010) Cell type–specific gene expression differences in complex tissues. Nat. Methods, 7, 287–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Boyle A.P., Davis S., Shulha H.P., Meltzer P., Margulies E.H., Weng Z., Furey T.S., Crawford G.E. (2008) High-resolution mapping and characterization of open chromatin across the genome. Cell, 132, 311–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Barski A., Cuddapah S., Cui K., Roh T.-Y., Schones D.E., Wang Z., Wei G., Chepelev I., Zhao K. (2007) High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell, 129, 823–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Bernstein B.E., Kamal M., Lindblad-Toh K., Bekiranov S., Bailey D.K., Huebert D.J., McMahon S., Karlsson E.K., Kulbokas E.J., Gingeras T.R.. et al. (2005) Genomic maps and comparative analysis of histone modifications in human and mouse. Cell, 120, 169–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Core L.J., Martins A.L., Danko C.G., Waters C.T., Siepel A., Lis J.T. (2014) Analysis of nascent RNA identifies a unified architecture of initiation regions at mammalian promoters and enhancers. Nat. Genet., 46, 1311–1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Murakawa Y., Yoshihara M., Kawaji H., Nishikawa M., Zayed H., Suzuki H. FANTOM Consortium Hayashizaki Y. (2016) Enhanced identification of transcriptional enhancers provides mechanistic insights into diseases. Trends Genet., 32, 76–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Palstra R.-J., Tolhuis B., Splinter E., Nijmeijer R., Grosveld F., de Laat W. (2003) The β-globin nuclear compartment in development and erythroid differentiation. Nat. Genet., 35, 190–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Buenrostro J.D., Wu B., Litzenburger U.M., Ruff D., Gonzales M.L., Snyder M.P., Chang H.Y., Greenleaf W.J. (2015) Single-cell chromatin accessibility reveals principles of regulatory variation. Nature, 523, 486–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Buenrostro J.D., Wu B., Chang H.Y., Greenleaf W.J. (2015) ATAC-seq: a method for assaying chromatin accessibility genome-wide. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol., 109, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Rotem A., Ram O., Shoresh N., Sperling R.A., Goren A., Weitz D.A., Bernstein B.E. (2015) Single-cell ChIP-seq reveals cell subpopulations defined by chromatin state. Nat. Biotechnol., 33, 1165–1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Kodzius R., Kojima M., Nishiyori H., Nakamura M., Fukuda S., Tagami M., Sasaki D., Imamura K., Kai C., Harbers M.. et al. (2006) CAGE: cap analysis of gene expression. Nat. Methods, 3, 211–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Plessy C., Bertin N., Takahashi H., Simone R., Salimullah M., Lassmann T., Vitezic M., Severin J., Olivarius S., Lazarevic D.. et al. (2010) Linking promoters to functional transcripts in small samples with nanoCAGE and CAGEscan. Nat. Methods, 7, 528–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Mahat D.B., Kwak H., Booth G.T., Jonkers I.H., Danko C.G., Patel R.K., Waters C.T., Munson K., Core L.J., Lis J.T. (2016) Base-pair-resolution genome-wide mapping of active RNA polymerases using precision nuclear run-on (PRO-seq). Nat. Protoc., 11, 1455–1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Core L.J., Waterfall J.J., Lis J.T. (2008) Nascent RNA sequencing reveals widespread pausing and divergent initiation at human promoters. Science, 322, 1845–1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Mayer A., Churchman L.S. (2016) Genome-wide profiling of RNA polymerase transcription at nucleotide resolution in human cells with native elongating transcript sequencing. Nat. Protoc., 11, 813–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Simonis M., Klous P., Splinter E., Moshkin Y., Willemsen R., de Wit E., van Steensel B., de Laat W. (2006) Nuclear organization of active and inactive chromatin domains uncovered by chromosome conformation capture–on-chip (4C). Nat. Genet., 38, 1348–1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Dostie J., Richmond T.A., Arnaout R.A., Selzer R.R., Lee W.L., Honan T.A., Rubio E.D., Krumm A., Lamb J., Nusbaum C.. et al. (2006) Chromosome conformation capture carbon copy (5C): a massively parallel solution for mapping interactions between genomic elements. Genome Res., 16, 1299–1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Fullwood M.J., Liu M.H., Pan Y.F., Liu J., Xu H., Mohamed Y., Bin, Orlov Y.L., Velkov S., Ho A., Mei P.H.. et al. (2009) An oestrogen-receptor-α-bound human chromatin interactome. Nature, 462, 58–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Lieberman-Aiden E., van Berkum N.L., Williams L., Imakaev M., Ragoczy T., Telling A., Amit I., Lajoie B.R., Sabo P.J., Dorschner M.O.. et al. (2009) Comprehensive mapping of long-range interactions reveals folding principles of the human genome. Science, 326, 289–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Nagano T., Lubling Y., Stevens T.J., Schoenfelder S., Yaffe E., Dean W., Laue E.D., Tanay A., Fraser P. (2013) Single-cell Hi-C reveals cell-to-cell variability in chromosome structure. Nature, 502, 59–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]