Abstract

Glycaemic traits such as fasting and post-challenge glucose and insulin measures, as well as glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), are used to diagnose and monitor diabetes. These traits are risk factors for cardiovascular disease even below the diabetic threshold, and their study can additionally yield insights into the pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes. To date, a diverse set of genetic approaches have led to the discovery of over 97 loci influencing glycaemic traits. In this review, we will focus on recent advances in the genetic aetiology of glycaemic traits, and the resulting biological insights. We will provide a brief overview of results ranging from common, to low- and rare-frequency variant-trait association studies, studies leveraging the diversity across populations, and studies harnessing the power of genetic and genomic approaches to gain insights into the biological underpinnings of these traits.

Introduction

Since their advent in 2005 (1), genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have been very successful at identifying common variant (minor allele frequency (MAF) > 5%) trait associations, with over 30,000 unique associations described to date (2). The type 2 diabetes (T2D) field has been no exception, with the number of loci robustly associated with T2D risk rising from three [PPARG, KCNJ11 and TCFL2 (3–5)] prior to the GWAS-Era, to 128 (6,7). Fasting and post-challenge glycaemic measures, and glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), have also been the subject of intense genetic research as they are used to diagnose and monitor T2D, and are important risk factors for cardiovascular disease even within the non-diabetic range. For example, studies have found that patients diagnosed using either fasting (FG) or 2-h glucose (2hG) have distinct cardiometabolic risk (8), with 2hG being a better predictor of cardiovascular mortality than FG (9). Similarly, glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) which reflects average glycaemia over the 2-3 month lifespan of a red blood cell, is an accepted diagnostic test for diabetes (10), but also predicts future vascular complications (11). Furthermore, insulin resistance, commonly measured using proxy phenotypes fasting insulin (FI) and insulin resistance by homeostasis model assessment [HOMA-IR (12)], is often associated with obesity or with limited peripheral adipose tissue capacity (13), and is an important risk factor for T2D. However, more sophisticated glycaemic measures such as the insulin suppression test or euglycemic clamp (considered the ‘gold standard’ estimate of peripheral insulin sensitivity) or proinsulin [adjusted for FI, equivalent to the proinsulin:insulin ratio, an indicator of beta-cell stress (14)], may, in combination with other glycaemic traits (FG, 2hG, HOMA-B and HbA1c), provide insights into diabetes pathophysiology, and possible disease stratification.

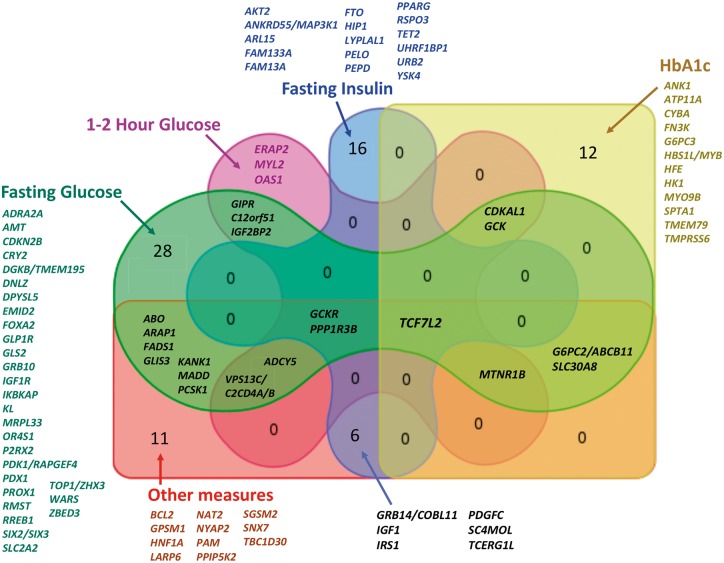

The application of a series of genetic approaches to these traits have to date yielded over 97 trait-associated loci (Table 1, Fig. 1). In this review, we will focus on the progress made in recent years and will briefly describe: a) insights from common variant (MAF ≥ 5%) associations; b) results from approaches that expand the allelic frequency range to low- and rare- variant associations; c) results from diverse populations; d) early biological and functional insights and e) application of results to T2D.

Table 1.

Loci influencing glycaemic traits

| Locus | Chr | Index SNP | Refs. | Ancestry | Alleles [E/O] | Type of variant | EAF | Effect Size (SE) | P-value | Trait |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABO | 9 | rs505922 | (38) | EA | C/T | Intronic | 0.47 | −0.038 (0.006) | 3.80 × 10−9 | Disposition index |

| rs651007 | (39) | EA+AA | A/G | Upstream | 0.20 | 0.020 (0.004) | 1.30 × 10−8 | FG | ||

| ADCY5b | 3 | rs11708067 | (80) | EA | A/G | Intronic | 0.78 | 0.027 (0.003) | 1.70 × 10−14 | FG |

| rs2877716 | (89) | EA | C/T | Intronic | 0.77 | −0.023 (0.004) | 3.6 × 10−8 | HOMA-B | ||

| 0.09 (0.01) | 4.19 × 10−16 | 2hG_adjBMI | ||||||||

| ADRA2A | 10 | rs10885122 | (80) | EA | G/T | Intergenic | 0.87 | 0.022 (0.004) | 9.70 × 10−8 | FG |

| AKT2 | rs184042322 | (60) | EA | T/G | P50T | 0.012 | 10.400 (1.990) | 9.98 × 10−10 | FI | |

| AMT (RBMA6b) | 3 | rs11715915 | (6) | EA | C/T | R318R | 0.68 | 0.012 (0.002) | 4.90 × 10−8 | FG |

| ANK1 (WARSb, NKX6-3b) | 8 | rs6474359 | (90) | EA | T/C | Intronic | 0.97 | 0.058 (0.011) | 1.18 × 10−8 | HbA1c |

| rs4737009 | (49) | EAA | A/G | Intronic | 0.24 | 0.027 (0.004) | 6.11 × 10−12 | HbA1c | ||

| rs4737009 | A/G | Intronic | 0.51 | 0.080 (0.010) | 1.10 × 10−15 | HbA1c | ||||

| ANKRD55/MAP3K1 | 5 | rs459193 | (22) | EA | G/A | Intergenic | 0.73 | 0.015 (0.002) | 1.12 × 10−10 | FI_adjBMI |

| ARAP1 (STARD10b) | 11 | rs11603334 | (22) | EA | G/A | Intronic | 0.83 | 0.019 (0.003) | 1.10 × 10−11 | FG |

| (24) | 0.85 | −0.093 (0.005) | 3.20 × 10−102 | Proinsulin | ||||||

| ARL15 | 5 | rs4865796 | (22) | EA | A/G | Intronic | 0.67 | 0.015 (0.003) | 2.10 × 10−8 | FI |

| 0.015 (0.002) | 2.20 × 10−12 | FI_adjBMI | ||||||||

| ATP11A | 13 | rs7998202 | (90) | EA | G/A | Upstream | 0.14 | 0.031 (0.005) | 5.24 × 10−9 | HbA1c |

| BCL2 | 18 | rs12454712 | (26) | EA | T/C | Intronic | 0.58 | 0.050 (0.010) | 1.9 × 10−8 | ISI_adjBMI |

| C12orf51 (HECTD4) | 12 | rs2074356 | (33) | EAA | T/NR | Intronic | NR | −0.061 (0.008) | 6.03 × 10−14 | FG |

| −0.321 (0.039) | 1.04 × 10−16 | 1hGlu | ||||||||

| −0.165 (0.028) | 5.91 × 10−09 | 2hG | ||||||||

| CDKAL1 | 6 | rs9368222 | (22) | EA | A/C | Intronic | 0.28 | 0.014 (0.002) | 1.00 × 10−9 | FG |

| rs7747752 | (91) | EAA | C/G | Intronic | 0.48 | 0.016 (0.002) | 4.54 × 10−11 | FG_adjBMI | ||

| rs7772603 | (49) | EAA | C/T | Intronic | 0.42 | −0.310 (NR) | 1.50 × 10−8 | HbA1c | ||

| rs9348440 | (33) | EAA | A/NR | Intronic | NR | 0.060 (0.010) | 3.50 × 10−8 | HbA1c | ||

| 0.246 (0.028) | 3.13 × 10−19 | 1hGlu | ||||||||

| CDKN2B | 9 | rs10811661 | (22) | EA | T/C | Upstream | 0.82 | 0.024 (0.003) | 5.60 × 10−18 | FG |

| 0.023 (0.003) | 5.12 × 10−15 | FG_adjBMI | ||||||||

| CRY2 | 11 | rs11605924 | (80) | EA | A/C | Intronic | 0.49 | 0.015 (0.003) | 8.10 × 10−8 | FG |

| CYBA | 16 | rs9933309 | (49) | EAA | C/T | Intronic | 0.63 | 0.070 (0.010) | 1.10 × 10−8 | HbA1c |

| DGKBb/TMEM195 | 7 | rs2191349 | (80) | EA | T/G | Intergenic | 0.52 | 0.030 (0.003) | 5.30 × 10−29 | FG |

| DNLZ | 9 | rs3829109 | (22) | EA | G/A | Intronic | 0.71 | 0.017 (0.003) | 1.10 × 10−10 | FG |

| DPYSL5 | 2 | rs1371614 | (92) | EA | T/C | Intronic | 0.25 | 0.020 (0.006) | 1.33 × 10−12 | FG_adjBMI |

| 0.015 (0.006) | 0.00021 | FG_BMI30 | ||||||||

| EMID2 | 7 | rs6947345 | (93) | EA | C/T | Intronic | 0.98 | 0.162 (0.029) | 3.80 × 10−8 | FG |

| ERAP2 | 5 | rs1019503 | (22) | EA | A/G | 3’UTR | 0.48 | 0.063 (0.011) | 8.90 × 10−9 | 2hG |

| FADS1b | 11 | rs174550 | (80) | EA | T/C | Intronic | 0.64 | 0.017 (0.003) | 8.30 × 10−9 | FG |

| −0.020 (0.003) | 5.30 × 10−10 | HOMA-B | ||||||||

| FAM133A | X | rs213676 | (46) | AA | C/G | Intergenic | 0.98 | 0.147 (NR) | 2.37 × 10−8 | FI_adjBMI |

| FAM13A | 4 | rs3822072 | (22) | EA | A/G | Intronic | 0.48 | 0.012 (0.002) | 1.90 × 10−8 | FI_adjBMI |

| FN3K | 17 | rs1046896 | (90) | EA | T/C | Upstream | 0.31 | 0.035 (0.003) | 1.57 × 10−26 | HbA1c |

| FOXA2b | 20 | rs6048205 | (92) | EA | A/G | Downstream | 0.95 | 0.023 (0.012) | 0.0014 | FG_BMI30 |

| rs6113722 | (22) | EA | G/A | Downstream | 0.96 | 0.035 (0.005 | 2.50 × 10−11 | FG | ||

| FTO | 16 | rs1421085 | (22) | EA | C/T | Intronic | 0.42 | 0.020 (0.003) | 1.90 × 10−15 | FI |

| G6PC2b/ABCB11 | 2 | rs560887 | (80) | EA | C/T | Intronic | 0.70 | 0.075 (0.003) | 8.50 × 10−122 | FG |

| rs552976 | (90) | EA | G/A | Intronic | 0.62 | −0.042 (0.004) | 7.60 × 10−29 | HOMA-B | ||

| rs138726309 | (40) | EA | T/C | H177Y | 0.01 | 0.032 (0.004) | 1.00 × 10−17 | HbA1c | ||

| rs492594 | (49) | EAA | C/G | V219L | 0.48 | 0.047 (0.003) | 8.16 × 10−18 | HbA1c | ||

| rs3755157 | T/C | Intronic | 0.34 | −0.102 (-0.02) | 3.10 × 10−8 | FG_adjBMI | ||||

| 0.02 (-0.004) | 6.00 × 10−9 | FG_adjBMI | ||||||||

| 0.07 (0.01) | 2.80 × 10−11 | HbA1c | ||||||||

| G6PC3 | 17 | rs12602486 | (50) | Malay | G/T | Downstream | 0.03 | −0.362 (0.035) | 1.00 × 10−4 | HbA1c |

| GCKb | 7 | rs4607517 | (80) | EA | A/G | Upstream | 0.16 | 0.062 (0.004) | 1.20 × 10−44 | FG |

| rs6975024 | (22) | EA | C/T | Upstream | 0.15 | 0.103 (0.016) | 5.20 × 10−11 | 2hG | ||

| rs1799884 | (90) | EA | C/T | Upstream | 0.18 | 0.038 (0.004) | 1.45 × 10−20 | HbA1c | ||

| rs1799884 | (33) | EAA | A/NR | Intronic | NR | 0.063 (0.007) | 4.53 × 10−18 | FG | ||

| 0.208 (0.035) | 2.82 × 10−9 | 1hGlu | ||||||||

| 0.162 (0.026) | 2.59 × 10−10 | 2hG | ||||||||

| GCKRb | 2 | rs780094 | (80) | EA | C/T | Intronic | 0.62 | 0.029 (0.003) | 1.70 × 10−24 | FG |

| rs1260326 | (89) | T/C | L446P | 0.42 | 0.032 (0.004) | 3.60 × 10−19 | FI | |||

| 0.035 (0.004) | 5.0 × 10−20 | HOMA-IR | ||||||||

| 0.100 (0.01) | 7.05 × 10−11 | 2hG_adjBMI | ||||||||

| GIPR | 19 | rs2302593 | (22) | EA | C/G | Intronic | 0.50 | 0.014 (0.002) | 9.30 × 10−10 | FG |

| rs10423928 | (89) | EA | A/T | Downstream | 0.18 | 0.09 (0.01) | 1.98 × 10−15 | 2hG_adjBMI | ||

| GLIS3 | 9 | rs7034200 | (80) | EA | A/C | Intronic | 0.49 | 0.018 (0.003) | 1.20 × 10−9 | FG |

| −0.020 (0.004) | 8.9 × 10−9 | HOMA-B | ||||||||

| GLP1R | 6 | rs10305492 | (39) | EA+AA | A/G | A316T | 0.01 | −0.09 (0.013) | 3.40 × 10−12 | FG |

| (40) | EA | 0.02 | −0.073 (0.015) | 4.60 × 10−7 | FG_adjBMI | |||||

| GLS2 | 12 | rs2657879 | (22) | EA | G/A | L581P | 0.18 | 0.016 (0.003) | 3.90 × 10−8 | FG_adjBMI |

| GPSM1 | 9 | rs60980157 | (38) | EA | T/C | S391L | 0.30 | 0.072 (0.013) | 1.4 × 10−8 | Insulinogenic index |

| GRB10 | 7 | rs6943153 | (22) | EA | T/C | Intronic | 0.34 | 0.015 (0.002) | 1.60 × 10−12 | FG |

| GRB14/COBL11 | 2 | rs10195252 | (22) | EA | T/C | Upstream | 0.59 | 0.016 (0.003) | 4.90 × 10−7 | FI |

| rs7607980 | (92) | EA | T/C | N939D | 0.60 | 0.017 (0.002) | 1.30 × 10−10 | FI_adjBMI | ||

| rs7607980 | (40) | EA | T/C | N939D | 0.86 | 0.039 (0.008)c | 4.90 × 10−7 | FI_BMI30 | ||

| 0.89 | −0.071 (0.030) | 3.00 × 10−13 | HOMA-IR | |||||||

| 0.030 (0.006) | 6.70 × 10−8 | FI_adjBMI | ||||||||

| HBS1L/MYB | 6 | rs9399137 | (49) | EAA | T/C | Intronic | 0.69 | 0.07 (0.01) | 8.50 × 10−15 | HbA1c |

| HFE | 6 | rs1800562 | (90) | EA | G/A | C282Y | 0.94 | 0.063 (0.007) | 2.59 × 10−20 | HbA1c |

| HIP1 | 7 | rs1167800 | (22) | A/G | Intronic | 0.54 | 0.016 (0.003) | 2.60 × 10−9 | FI | |

| HK1 | 10 | rs16926246 | (90) | EA | C/T | Intronic | 0.90 | 0.089 (0.004) | 3.11 × 10−54 | HbA1c |

| HNF1A | 12 | rs2650000 | (38) | EA | A/C | Intergenic | 0.46 | −0.076 (0.012) | 5.0 × 10−10 | Insulinogenic index |

| IGF1 | 12 | rs35767 | (80) | EA | G/A | Upstream | 0.85 | 0.010 (0.006) | 0.10 | FI |

| rs35747 | (92) | EA | A/G | 0.82 | 0.013 (0.006) | 0.04 | HOMA-IR | |||

| 0.021 (0.004) | 8.85 × 10−10 | FI_adjBMI | ||||||||

| IGF1R | 15 | rs2018860 | (48) | EAA | A/T | Intronic | 0.46 | 0.031 (0.006) | 2.99 × 10−8 | FG_adjBMI |

| IGF2BP2 | 3 | rs7651090 | (22) | EA | G/A | Intronic | 0.31 | 0.013 (0.002) | 1.75 × 10−8 | FG |

| 0.30 | 0.064 (0.012) | 4.50 × 10−8 | 2hG_adjBMI | |||||||

| IKBKAP | 9 | rs16913693 | (22) | EA | T/G | Intronic | 0.97 | 0.043 (0.007) | 3.50 × 10−11 | FG |

| IRS1 | 2 | rs2943634 | (92) | EA | C/A | Downstream | 0.66 | 0.021 (0.010) | 0.0036 | FI_BMI30 |

| rs2972143 | (22) | EA | G/A | Downstream | 0.62 | −0.015 (0.018) | 2.00 × 10−10 | HOMA-IR | ||

| rs2943645 | (22) | EA | T/C | Downstream | 0.63 | 0.014 (0.003) | 3.20 × 10−8 | FI | ||

| 0.019 (0.002) | 2.30 × 10−19 | FI_adjBMI | ||||||||

| KANK1 | 9 | rs3824420 | (38) | EA | A/G | R667H | 0.03 | 0.107 (0.018) | 1.6 × 10−9 | Proinsulin AUC0-30 |

| rs10815355 | (48) | EAA | T/G | Intronic | 0.22 | 0.045 (0.007) | 1.26 × 10−9 | FG_adjBMI | ||

| KL | 13 | rs576674 | (22) | EA | G/A | Upstream | 0.15 | 0.017 (0.003) | 2.30 × 10−8 | FG |

| LARP6 | 15 | rs1549318 | (24) | EA | T/C | Downstream | 0.61 | 0.019 (0.005) | 2.4 × 10−10 | Proinsulin |

| LYPLAL1 | 1 | rs2820436 | (22) | EA | C/A | Downstream Downstream | 0.67 | 0.015 (0.003) | 4.40 × 10−9 | FI |

| rs4846565 | (22) | EA | G/A | Downstream | 0.67 | 0.013 (0.002) | 1.80 × 10−9 | FI_adjBMI | ||

| rs2785980 | (92) | EA | T/C | 0.67 | 0.018 (0.010) | 0.097 | FI_BMI30 | |||

| MADDb (ACP2b) | 11 | rs7944584 | (80) | EA | A/T | Intronic | 0.75 | 0.021 (0.003) | 5.10 × 10−11 | FG |

| rs10501320 | (24) | EA | G/C | Intronic | 0.72 | 0.081 (0.006) | 1.1 × 10−88 | Proinsulin | ||

| rs10838687 | (24) | EA | T/G | Intronic | 0.80 | 0.025 (0.005) | 6.9 × 10−12 | Proinsulin | ||

| rs35233100 | (38) | EA | T/C | R766X | 0.04 | −0.100 (0.013)a | 7.6 × 10−15 | Fasting proinsulin | ||

| MRPL33 | 2 | rs3736594 | (92) | EA | A/C | Intronic | 0.28 | 0.022 (0.003) | 5.22 × 10−16 | FG_adjBMI |

| MTNR1Bb | 11 | rs10830963 | (80) | EA | G/C | Intronic | 0.30 | 0.067 (0.003) | 1.10 × 10−102 | FG |

| rs1387153 | (90) | EA | T/C | Upstream | 0.27 | −0.034 (0.004) | 1.1 × 10−22 | HOMA-B | ||

| rs10830962 | (33) | EAA | C/NR | Upstream | NR | 0.024 (0.004) | 3.00 × 10−9 | HbA1c | ||

| 0.028 (0.004) | 3.96 × 10−11 | HbA1c | ||||||||

| 0.041 (0.006) | 4.84 × 10−13 | FG | ||||||||

| 0.191 (0.027) | 3.24 × 10−12 | 1hGlu | ||||||||

| MYL2 | 12 | rs12229654 | (33) | EAA | G/NR | Intergenic | NR | −0.277 (0.039) | 8.83 × 10−13 | 1hGlu |

| MYO9B | 19 | rs11667918 | (49) | EAA | C/T | Intronic | 0.62 | 0.060 (0.010) | 9.00 × 10−12 | HbA1c |

| NAT2c | 8 | rs1208 | (25) | EA | A/G | K268R | 0.57 | −0.130 (0.03) | 9.81 × 10−7 | Insulin sensitivity |

| NYAP2 | 2 | rs13422522 | (26) | EA | C/G | Intergenic | 0.77 | −0.060 (0.010) | 1.2 × 10−11 | ISI_adjBMI |

| OAS1 | 12 | rs11066453 | (33) | EAA | G/NR | Intronic | NR | −0.242 (0.041) | 4.54 × 10−09 | 1hGlu |

| OR4S1 | 11 | rs1483121 | (92) | EA | G/A | Downstream | 0.86 | 0.006 (0.008) | 0.034 | FG_BMI30 |

| P2RX2 | 12 | rs10747083 | (22) | EA | A/G | Upstream | 0.66 | 0.013 (0.002) | 7.60 × 10−9 | FG |

| PAM | 5 | rs35658696 | (38) | EA | G/A | D563G | 0.05 | −0.152 (0.027) | 1.9 × 10−8 | Insulinogenic index |

| PCSK1b | 5 | rs13179048 | (92) | EA | C/A | Downstream | 0.69 | 0.027 (0.013) | 0.022 | FG_BMI30 |

| rs4869272 | (22) | EA | T/C | Downstream | 0.69 | 0.018 (0.002) | 1.00 × 10−15 | FG | ||

| rs6234 | (40) | EA | C/G | Q665E | 0.28 | −0.022 (-0.004) | 3.00 × 10−8 | FG_adjBMI | ||

| rs6235 | (40) | EA | G/C | S690T | 0.28 | −0.022 (-0.004) | 4.10 × 10−8 | FG_adjBMI | ||

| rs6235 | (24) | EA | G/C | S690T | 0.28 | 0.039 (0.005) | 9.8 × 10−27 | Proinsulin | ||

| PDGFC | 4 | rs4691380 | (92) | EA | C/T | Intronic | 0.67 | 0.020 (0.010) | 0.072 | FI_BMI30 |

| rs6822892 | (22) | EA | A/G | Intronic | 0.68 | −0.003 (0.019) | 4.00 × 10−8 | HOMA-IR | ||

| 0.014 (0.002) | 2.60 × 10−10 | FI_adjBMI | ||||||||

| PDK1/RAPGEF4 | 2 | rs733331 | (48) | EAA | A/G | Intronic | 0.56 | 0.036 (0.006) | 6.98 × 10−11 | FG_adjBMI |

| PDX1b | 13 | rs2293941 | (92) | EA | A/G | Upstream | 0.22 | 0.016 (0.006) | 0.0078 | FG_BMI30 |

| rs11619319 | (22) | EA | G/A | Upstream | 0.23 | 0.019 (0.002) | 1.30 × 10−15 | FG | ||

| PELO | 5 | rs6450057 | (46) | EA | T/C | Intergenic | 0.37 | −0.011 (NR) | 9.21 × 10−5 | FI_adjBMI |

| AA | T/C | Intergenic | 0.40 | 0.027 (NR) | 3.11 × 10−6 | FI_adjBMI | ||||

| PEPD | 19 | rs731839 | (22) | EA | G/A | Intronic | 0.34 | 0.015 (0.003) | 1.70 × 10−8 | FI |

| 0.015 (0.002) | 5.10 × 10−12 | FI_adjBMI | ||||||||

| PPARGb | 3 | rs17036328 | (22) | EA | T/C | Intronic | 0.86 | 0.021 (0.003) | 3.60 × 10−12 | FI_adjBMI |

| PPIP5K2 | 5 | rs36046591 | (38) | EA | G/A | S1228G | 0.05 | −0.152 (0.027) | 2.3 × 10−8 | Insulinogenic index |

| PPP1R3B | 8 | rs4841132 | (92) | EA | A/G | Upstream | 0.10 | 0.054 (0.021) | 0.0031 | FG_BMI30 |

| rs983309 | (22) | EA | T/G | Upstream | 0.12 | 0.032 (0.016) | 0.00073 | FI_BMI30 | ||

| rs2126259 | (22) | EA | T/C | Upstream | 0.11 | −0.055 (0.028) | 2.00 × 10−8 | HOMA-IR | ||

| rs11782386 | (22) | EA | C/T | Upstream | 0.87 | 0.026 (0.003) | 6.30 × 10−15 | FG | ||

| 0.029 (0.004) | 3.80 × 10−14 | FI | ||||||||

| 0.099 (0.017) | 2.20 × 10−9 | 2hG | ||||||||

| 0.024 (0.003) | 3.30 × 10−13 | FI_adjBMI | ||||||||

| PROX1 | 1 | rs340874 | (80) | EA | C/T | Upstream | 0.52 | 0.013 (0.003) | 6.60 × 10−6 | FG |

| RMST | 12 | rs17331697 | (93) | EA | T/C | Intronic | 0.90 | 0.046 (0.007) | 1.30 × 10−11 | FG |

| RREB1b | 6 | rs17762454 | (22) | EA | T/C | Intronic | 0.26 | 0.014 (0.002) | 9.60 × 10−9 | FG_adjBMI |

| RSPO3 | 6 | rs2745353 | (22) | EA | T/C | Intronic | 0.51 | 0.014 (0.002) | 5.50 × 10−9 | FI |

| SC4MOL | 4 | rs17046216 | (45) | AA + West African | A/NR | Intergenic | NR | 0.180 (0.030) | 1.65 × 10−8 | FI_adjBMI |

| 0.190 (0.030) | 2.88 × 10−8 | HOMA-IR | ||||||||

| SGSM2 | 17 | rs4790333 | (24) | EA | T/C | Intronic | 0.45 | 0.015 (0.004) | 3.00 × 10−9 | Proinsulin |

| rs61741902 | (38) | EA | A/G | V996I | 0.01 | 0.126 (0.021)a | 8.70 × 10−10 | Fasting proinsulin | ||

| SIX2/SIX3 | 2 | rs895636 | (47) | EAA | T/C | Intergenic | 0.38 | 0.039 (0.006) | 9.99 × 10−13 | FG |

| SLC2A2b | 3 | rs11920090 | (80) | EA | T/A | Intronic | 0.87 | 0.02 (0.004) | 3.30 × 10−6 | FG |

| SLC30A8b | 8 | rs13266634 | (80) | EA | C/T | R325W | NR | 0.027 (0.004) | 5.50 × 10−10 | FG |

| rs11558471 | (94) | EA | C/T | 3’UTR | 0.70 | 0.02 (NR) | 5.00 × 10−8 | HbA1c | ||

| (22) | EA | A/G | 0.68 | 0.029 (0.002) | 7.80 × 10−37 | FG | ||||

| (24) | EA | A/G | 0.69 | 0.028 (0.005) | 3.1 × 10−18 | Proinsulin | ||||

| SNX7 | 1 | rs9727115 | (24) | EA | G/A | Intronic | 0.64 | 0.013 (0.005) | 2.40 × 10−10 | Proinsulind |

| SPTA1 | 1 | rs2779116 | (90) | EA | T/C | Intronic | 0.28 | 0.024 (0.004) | 2.75 × 10−9 | HbA1c |

| TBC1D30 | 12 | rs150781447 | (38) | EA | T/C | R279C | 0.02 | 0.204 (0.025) | 1.3 × 10−16 | Proinsulin AUC30-120 |

| TCERG1L | 10 | rs7077836 | (45) | AA + West African | T/NR | Intergenic | NR | 0.280 (0.050) | 7.50 × 10−9 | FI_adjBMI |

| 0.340 (0.050) | 4.86 × 10−20 | HOMA-IR | ||||||||

| TCF7L2 | 10 | rs7903146 | (22) | EA | T/C | Intronic | 0.28 | 0.022 (0.002) | 2.70 × 10−20 | FG |

| rs12243326 | (22) | EA | C/T | Intronic | 0.28 | −0.018 (0.003) | 6.10 × 10−11 | FI | ||

| (24) | EA | 0.30 | 0.032 (0.007) | 2.3 × 10−20 | Proinsulin | |||||

| (95) | EA | 0.28 | 0.05 (0.03) | 1.48 × 10−7 | HbA1c | |||||

| (89) | EA | 0.21 | 0.07 (0.01) | 4.23 × 10−10 | 2hG_adjBMI | |||||

| TET2 | 4 | rs9884482 | (22) | EA | C/T | Intronic | 0.35 | 0.017 (0.002) | 1.40 × 10−11 | FI |

| rs974801 | (22) | EA | G/A | Intronic | 0.39 | 0.014 (0.002) | 3.30 × 10−11 | FI_adjBMI | ||

| TMEM79 | 1 | rs6684514 | (49) | EAA | G/A | V147M | 0.76 | 0.09 (0.01) | 1.30 × 10−23 | HbA1c |

| TMPRSS6 | 22 | rs855791 | (90) | EA | A/G | V736A | 0.42 | 0.027 (0.004) | 2.74 × 10−14 | HbA1c |

| TOP1/ZHX3b | 20 | rs6072275 | (22) | EA | A/G | Intronic | 0.16 | 0.016 (0.003) | 1.70 × 10−8 | FG |

| UHRF1BP1 | 6 | rs4646949 | (92) | EA | T/G | Intronic | 0.75 | 0.009 (0.010) | 0.16 | FI_BMI30 |

| rs6912327 | (22) | EA | T/C | Intronic | 0.80 | 0.017 (0.003) | 2.30 × 10−8 | FI_adjBMI | ||

| URB2 | 1 | rs141203811 | (40) | EA | T/A | E594V | 0.001 | 0.282 (-0.066) | 3.10 × 10−7 | FI_adjBMI |

| VPS13C/C2CD4A/B | 15 | rs17271305 | (89) | EA | G/A | Intronic | 0.42 | 0.060 (0.010) | 4.11 × 10−8 | 2hG_adjBMI |

| rs11071657 | (80) | EA | A/G | Downstream | 0.63 | 0.008 (0.003) | 0.01 | FG | ||

| rs4502156 | (24) | EA | T/C | Downstream | 0.58 | 0.029 (0.004) | 3.5 × 10−20 | Proinsulin | ||

| WARS | 14 | rs3783347 | (22) | EA | G/T | Intronic | 0.79 | 0.017 (0.003) | 1.30 × 10−10 | FG |

| YSK4 | 2 | rs1530559 | (22) | EA | A/G | Intronic | 0.52 | 0.015 (0.003) | 3.40 × 10−8 | FI |

| ZBED3 | 5 | rs7708285 | (22) | EA | G/A | Intronic | 0.27 | 0.015 (0.003) | 1.20 × 10−8 | FG_adjBMI |

Chr, Chromosome; EA, European ancestry; EAA, East Asian ancestry; AA, African American ancestry; Allele, [E, Effect allele/O, Other allele]; EAF, Effect allele frequency; NR, Not reported/available; FG, fasting glucose (mmol/L); FG_adjBMI, fasting glucose BMI adjusted; FG_BMI30, Fasting glucose in individuals with BMI = 30 kg/m2; FI, fasting insulin (pmol/L); FI_adjBMI, fasting insulin BMI adjusted; 2hG, 2 h glucose (mmol/L); HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin (%); HOMA-B, β-cell function by homeostasis model assessment; HOMA-IR, insulin resistance by homeostasis model assessment; Proinsulin (pmol/L); ISI_adjBMI, Modified Stumvoll Insulin Sensitivity Index, adjusted for BMI. Effect estimates are taken from original references are all rounded to three decimal points.

Effect sizes for ISI are presented as the SD per effect allele.

Coefficient units are ln(pmol/l).

Likely effector transcript at the locus.

Signal at NAT2 did not reach genome-wide significance.

Signal at SNX7 reached genome-wide significance after adjusting for fasting glucose (P = 5.4 × 10−9).

Figure 1.

Venn diagram showing the overlap between the groups of glycaemic loci identified. Lists of loci (identified by the name of the closest gene to the index variant, or biologically plausible gene where known) unique to each trait, or overlapping between traits, are listed outside the diagram where that number is high, otherwise they are indicated in the figure. Loci were identified from large-scale meta-analyses with N∼108–133 K for FI and FG and N∼43–48 K for 2hrGlu, HbA1c, and HOMA-IR. Sample sizes for other glycaemic measures were much smaller, ranging from N∼16 K for ISI to just ∼1,000 participants for 1hrGlu.

Common Variant Trait Associations

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have transformed the landscape of glycaemic trait genetics. Prior to GWAS FG was associated with genetic variants in GCK (Glucokinase) (15). Subsequently, early GWAS replicated the GCK association (16,17) and identified novel associations with FG at G6PC2 (16,17) and GCKR (18–20). Aggregation of data through meta-analyses, primarily in populations of European ancestry in the setting of large consortia (such as the Meta-Analyses of Glucose and Insulin-related traits Consortium, MAGIC), and the development of targeted arrays such as the Metabochip (21), have increased the number of associations between common variants and the most commonly used glycaemic measures (FG, FI, 2hG and HbA1c) to over 70 (Table 1), accounting for <6% of phenotypic variance in Europeans (22,23).

Association with more sophisticated glycaemic measures, identified additional genome-wide significant loci, such as LARP6 and SGSM2 associated with fasting proinsulin (24), NAT2 associated with euglycemic clamp and insulin suppression test techniques (25), BCL2 and FAM19A2 associated with the modified Stumvoll Insulin Sensitivity Index (ISI) (a dynamic measure of whole-body insulin sensitivity) (26). These measures enabled detailed physiological characterization of existing loci (27–29), including establishment of the role of MTNR1B in decreased early phase insulin response (30). An alternative measure of impaired glucose tolerance, 1-h glucose (1hG), may warrant further research following studies investigating its potential utility (31,32), and the identification of novel loci MYL2, C12orf51 and OAS1 associated 1hG in Koreans (33) (Table 1).

The Contribution of Low Frequency and Rare Variants

The majority of genome-wide association signals are both common and non-coding, and recent efforts have focused on the contribution of rare (MAF < 1%) and low frequency (1% ≤ MAF < 5%) variants, and their role as possible causal variants. Current strategies include: 1) genotyping arrays targeting the exons (also known as ‘Exome Chips’) or with combined common variant backbone and exonic content; 2) genome- and exome –wide sequencing and 3) combined genotyping arrays and dense imputation using sequence based reference panels such as 1000 genomes (34), UK10K (35,36) and HRC (37).

Huyghe et al. (38) were the first to demonstrate the utility of exome-array genotyping. Using this approach in Finns, they found novel low-frequency coding variants at TBC1D30 (R279C, MAF = 2.0%) and KANK1 (R667H, MAF = 2.9%) associated with fasting proinsulin levels (and late/early-phase proinsulin to insulin conversion ratio, respectively) and two variants with MAF = 5.3%, and in near-perfect LD (r2=0.997) at PAM (D563G) and PPIP5K2 (S1228G) associated with insulin secretion (insulinogenic index). Novel low frequency variants at previously identified GWAS loci, SGSM2 (V996I, MAF 1.4%) and MADD (R766X, MAF = 3.7%) associated with fasting proinsulin, and common variants associated with insulin secretion or beta-cell function at GPSM1 (S391L), HNF1A (intergenic), and ABO (intronic) were also identified. Gene-based tests (aggregating rare/low frequency variants at the locus) identified significant associations with fasting proinsulin at TBC1D30, SGSM2 and ATG13, although conditional analyses suggested the ATG13 signal was partially driven by variants in MADD. Wessel et al. (39) identified a non-synonymous variant at GLP1R (A316T; rs10305492; MAF = 1.4%) associated with lower FG, early insulin secretion and type 2 diabetes risk, but higher 2hG (39). The same effort identified a gene-based signal at G6PC2, which was driven by three non-synonymous rare variants (H177Y, Y207S and S324P) and a stop variant (R283X). Further evidence of FG association at G6PC2 was provided by Mahajan et al. (40), who also found multiple rare coding variants at this gene (V219L, H177Y, Y207S), with evidence of loss of protein function, identifying G6PC2 as an effector transcript at the G6PC2/ABCB11 locus (Table 1). The same study identified 10 additional non-synonymous coding variants associated with FG or FI, of which eight mapped to known GWAS loci: GCKR (P446L), SLC30A8 (R325W), RREB1 (S1554Y), PCSK1 (S690T, Q665E), COBLL1 (N939D), TOP1 (N310S) and PPARG (P12A) (Table 1). Two novel loci, GLP1R [A316T, supporting result from (39)] and URB2 (E594V) were also identified. Despite this success only two association signals were low frequency variants, H177Y MAF 0.8% at G6PC2/ABCB11 and E594V MAF 0.1% at URB2, (Table 1), and the data supported PCSK1, RREB1 and ZHX3 as likely effector transcripts at the associated loci, with RREB1 also replicated in a type 2 diabetes study (7), confirming it as the probable effector gene for T2D at the SSR1 locus.

The UK10K Consortium (35) performed low depth (7x) whole-genome sequencing in 3,781 participants from two British cohorts (ALSPAC and TwinsUK) and conducted association analyses with 31 phenotypes available in both cohorts, replicating common variant associations at G6PC2-ABCB11 with FG. Subsequent fine-mapping efforts identified missense variant associations as the causal variant or within the credible set of causal variants at GCKR (L446P) and SLC30A8 (R325W) (41).

Transferability to Other Ancestries and Fine Mapping

Driven by the availability of large sample sizes, the majority of early GWAS studies were performed in populations of European ancestry. Since then, efforts have expanded to diverse populations, leveraging differences in allele frequency and linkage disequilibrium (LD) structure, to harness power for novel locus discovery and fine-mapping (42). While genetic effect sizes for common variants are largely consistent across ancestry groups, allele frequencies can vary (43,44), improving power for association in certain populations.

Studies in African Americans have identified SC4MOL and TCERG1L associated with FI and insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) (45), and FAM133A and PELO associated with FI, where PELO was identified in a trans-ethnic meta-analysis combining African American data with publicly available European summary statistics from MAGIC (46). In East Asians, studies have identified SIX2-SIX3, C12orf51, PDK1-RAPGEF4, KANK1 and IGF1R associated with FG (33,47,48), MYL2, C12orf51 and OAS1 associated with 1-2hG (33) and HBS1L-MYB, CYBA, MYO9B and G6PC3 for HbA1c (49,50) (Table 1).

More focused replication and fine-mapping efforts have also been carried out in African Americans (51–53), Asian populations (54,55) and an admixed Mexican population (56). Exact (the same index variant) and local replication has replicated variants in or near MNTR1B, G6PC2-ABCB11, GCK, IRS1, TCF7L2, DGKB, FADS1, GCKR, SLC30A8 and ZMAT4 associated with FG and GCKR with FI. These results suggest partial locus transferability but are limited in power by the relatively modest sample sizes (largest discovery sample sizes, N∼20-25 K) compared to the much larger European ancestry efforts (N∼ 108-133 K for FI and FG) that have led to the discovery of the loci being assessed. Nonetheless they highlight the utility of diverse populations to refine association signals, to fewer probable casual variants. For example, inclusion of African American samples in a trans-ethnic fine-mapping approach reduced the credible set (smallest set of SNPs that accounts for 99% of the posterior probability of containing the causal variant at the locus) at GCK and ADCY5 for FG, PPP1R3B for FI, and GCKR for FG and FI, to a single SNP (46).

In contrast, population isolates derive from a small number of founder individuals, have reduced genetic diversity and higher levels of LD, and enrichment of some rare alleles following the initial bottleneck, thus increasing power and facilitating genetic discovery (57,58). Successful outcomes are the TBC1D4 locus identified in Greenland strongly associated with 2hG and 2hI (59), and most recently, a variant (P50T) in AKT2 associated with a large effect (12% increase) on FI, with MAF 1.1% in Finns, but virtually absent (MAF ≤0.2%) in the individuals from other ancestries (60).

Biological and Functional Insights

As mentioned earlier, most glycaemic trait genetic variant associations map within non-coding regions, with the underlying causal or effector transcript hard to establish, requiring fine-mapping which often necessitates other genomic evidence to establish a functional link between associated variants and underlying biology. Recent studies have shown that pancreatic islet enhancers are enriched with FG associated loci (61,62), and that pancreatic islet eQTLs provide important clues for candidate effector transcripts at FG associated loci (63,64). For some of these loci, the eQTL provides compelling confirmatory evidence for the biological candidate loci at these association signals [e.g. ADCY5, DGKB at the DGKB/TMEM195 locus, FADS1 and MTNR1B (63), replicating previous findings at this locus (64,65)]. At the ARAP1 locus a recent study (63) suggests STARD10 is the likely effector transcript, which is in contrast with earlier data (66), but consistent with another more recent report (67). At the MADD locus two potential effector transcripts were identified, MADD and ACP2 (63), supporting evidence for MADD is provided by a beta-cell specific mouse model which showed that Madd plays a role in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (68), however the mouse phenotype did not provide any clues regarding the insulin processing effects also strongly associated with MADD (24). ACP2, on the other hand, encodes a lysosomal protein; the role of lysomes in the degradation of ageing insulin granules (69) was hypothesised by the authors (63) as a possible link for the fasting glucose and prosinsulin association signals. WARS, NKX6-3 (at the ANK1 locus) and RBMA6 (at the AMT locus) were also implicated as plausible effector transcripts but the mechanism through which they impact islet function, is as yet, unknown (63).

Loci associated with insulin resistance have been more recalcitrant to the GWAS approach and thus the number of established loci and effector transcripts is much smaller (Table 1). Recently, a blood transcriptomic genome-wide analysis (TWAS) combined with eQTL analysis, identified a trans-eQTL (rs592423) where the A-allele was associated with higher IGF2BP2 transcript levels and higher fasting insulin, suggesting this is the effector transcript at this locus (70). The TWAS also identified several genes with established roles in metabolic traits, namely IRS2 and FOXO4 involved in insulin signalling, and three genes involved in adipocyte or adipokine biology (ITLN1, PID1, ADIPOR1) (70). Another recent approach focused on identifying loci simultaneously associated with higher levels of FI adjusted for BMI, higher levels of triglycerides and lower levels of HDL, a hallmark of insulin resistance and of the condition lipodystrophy. In total, 53 associated loci were identified which when combined in a genetic risk score, were associated with increased T2D and coronary heart disease risk, but lower peripheral adipose tissue. The same loci also provided the first evidence of polygenic influence in familial lipodystrophy type 1, a severe form of insulin resistance previously thought to be monogenic in origin. Overall, these data suggested that impaired peripheral adipose tissue capacity may be an important mechanism influencing insulin resistance and is likely to be an important aetiological contributor to insulin-resistant cardiometabolic disease (13). The importance of adipose tissue differentiation in insulin resistant states was known from monogenic lipodystrophy due to mutations in PPARG (71,72) and has also more recently been demonstrated to be an important aetiological factor in T2D predisposition (73).

Complementing functional regulatory associations, the identification of multiple rare missense variants shown to affect protein function, and that contribute to a gene-based association signal, is a strong indicator that the effector transcript has been identified [e.g. G6PC2 (39,40), SLC30A8 (74) and PPARG (73)]. Similarly, single-point associations shown, or predicted, to have an effect on protein function [e.g. the P50T variant at AKT2 associated with FI (60) and the S690T and Q665E at PCSK1 associated with proinsulin and FG (24,40)], or mapping proximal to classical candidate loci are also strong indicators that the effector transcript is likely to map to those specific genes. This approach suggested that SLC2A2 (encoding GLUT2), GCK, GCKR, FOXA2 and PDX1 are the likely effector transcripts at these loci (Table 1). SLC2A2 encodes GLUT2, the main glucose transporter in the islets of rodents but not of humans, where GLUT1 and GLUT3 predominate both in islets and beta-cells, suggesting that the role of variants at this gene are likely to be mediated through effects on other metabolic tissues (75). Recently, another study has supported this hypothesis, where the C allele of rs8192675 in SLC2A2 was associated with a greater metformin-induced decrease in HbA1c levels, and was also shown to be an eQTL for GLUT2 in human liver samples. This suggested a role of hepatic GLUT2 in metformin action and glucose metabolism with significant clinical impact, and proposed as a biomarker for precision medicine (76). The importance of the liver in glucose homeostasis and FG levels, was also confirmed by studies of the P446L variant in GCKR, which demonstrated that this variant affected GCKR inhibition of GCK which was predicted to promote hepatic glucose metabolism with consequent decrease in FG (77). A number of glycaemic trait-associated loci map within, or proximal to, genes associated with a range of Mendelian metabolic disorders namely SLC2A2 (OMIM # 227810), GCK (OMIM # 125851), PPARG (OMIM # 604367), PCSK1 (OMIM # 600955), PDX1 (OMIM # 606392), GLIS3 (OMIM # 610199), IGF1 (OMIM # 608747) and HNF1A (OMIM # 600496) providing additional biological support for their candidacy as effector transcripts at these loci, and suggesting a role for rare penetrant and common variants influencing familial or polygenic traits, respectively.

These data combined, highlight genes involved in glucose regulation, insulin processing, secretion and response, and transcription factors with an established role in pancreas development as important mechanisms influencing glycaemic traits. Early GWAS results highlighted for the first time in humans, the role of loci involved in circadian rhythm [MTNR1B (65,78,79) and CRY2 (80)] in glucose metabolism. These results have been replicated in many additional studies, and subsequent analyses have shown that the associations at these loci are season-dependent (81) and that clock genes are regulated in pancreatic islet cells confirming that perturbations in circadian clock components are likely important in glucose homeostasis (82). The role of circadian clock in metabolism and possible therapeutic opportunities has recently been extensively reviewed (83), though the exact mechanism of how MTNR1B is likely to affect glucose homeostasis and diabetes risk remains the subject of some controversy (84,85).

Glycaemic Traits and T2D

Fasting glucose is used to diagnosis type 2 diabetes (T2D) however, GWAS studies have demonstrated that the genetic architecture of these two traits does not fully overlap (22,80,86), suggesting that raising fasting glucose per se is insufficient to confer T2D risk and that pathophysiology is likely conditional on the affected pathway. The availability of detailed measures of glycaemia has thus helped demonstrate that a diverse set of mechanisms are involved in conferring risk of T2D. To date, T2D risk loci have been grouped into five distinct groups: a) those loci whose primary effect appears to be on insulin sensitivity (PPARG, KLF14, IRS1, GCKR); b) loci associated with decreased insulin secretion and with fasting hyperglycaemia (MTNR1B, GCK); c) a single locus, ARAP1, associated with impaired proinsulin processing; d) a large cluster of loci influencing insulin processing and secretion with modest or no detected effects on fasting glucose levels (TCF7L2, SLC30A8, HHEX/IDE, CDKAL1, CDKN2A/2B, PROX1, THADA, ADCY5, DGKB/TMEM195); and e) a large set of 20 loci that despite influencing T2D risk did not have clear associations with any of the available measures of glycaemia and which may correspond to novel mechanisms influencing diabetes by as yet not understood biology (87). Similar earlier analyses of loci influencing fasting and post-challenge glucose measures also suggested similar diverse mechanisms influencing these traits (27).

A recent large-scale trans-ethnic meta-analyses of GWAS for HbA1c has expanded the number of HbA1c-associated loci to 60, and importantly highlighted that the genetic architecture of the trait differed in African Americans compared to the other ancestries studied (European, East and South Asians). In African Americans, a single variant in the G6PD gene (G202A) responsible for glucose-6-phosphate deficiency, accounted for a significant fraction of the variance in the trait (14.4%) and led to a substantial decrease in HbA1c values in hemizygous men (0.81%-units) and homozygous women (0.68%-units). This variant, if unaccounted for, could lead to up to 2% of African Americans with T2D to remain undiagnosed, highlighting the importance of studying glycaemic traits in diverse populations in order to avoid racial health disparities in the application of precision medicine (23).

Summary and Future Directions

In conclusion, large-scale genetic association analyses, combined with information on genomic features (enhancers, expression QTLs, TWAS) and high- throughput functional assays (88) have provided an increasingly growing list of loci associated with continuous glycaemic measures. The genetic architecture of these traits is comprised of many common variants of modest effect, mostly mapping to non-coding regions, with evidence of enrichment in active islet enhancers, and some overlap with monogenic loci involved in various disorders of metabolism. Genetic locus overlap between several glycaemic traits can be observed, most notably between FG and many of the other glycaemic traits, including T2D, though this number is likely to change as larger more powered studies become available (Fig. 1). Interestingly, FG and FI, have limited overlap in associated loci which may be a reflection of underlying differences in physiology affecting these traits (Fig. 1). These approaches have revealed some expected, and some novel pathways involved in glucose homeostasis, with recent efforts highlighting a number of low-frequency or rare missense variants affecting protein function, which provide compelling evidence for the effector transcript at a given locus. Studies of diverse populations have demonstrated, for the most part, the transferability of glycaemic trait-associated loci across ancestries and highlighted the power of isolated populations to identify variants of larger effect sizes. More recently, large-scale trans-ethnic genetic analysis of HbA1c highlighted the need for more powered studies on diverse ancestries to avoid health disparities in the application of genomics to the clinic. Future efforts combining sequencing approaches, increased sample sizes (particularly in non-European ancestries), understanding of the non-coding regions of the genome and the integration of other ‘omics’ data will continue to improve understanding of the biology underlying glycaemic traits and how they impact on disease.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all participants and researchers of the cited studies, and would like to apologise to colleagues whose work we were unable to cite due to space constraints.

Conflict of Interest statement. None declared.

Funding

Wellcome Trust (WT098051). Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by Wellcome Trust WT098051.

References

- 1. Klein R.J., Zeiss C., Chew E.Y., Tsai J.Y., Sackler R.S., Haynes C., Henning A.K., SanGiovanni J.P., Mane S.M., Mayne S.T.. et al. (2005) Complement factor H polymorphism in age-related macular degeneration. Science, 308, 385–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. MacArthur J., Bowler E., Cerezo M., Gil L., Hall P., Hastings E., Junkins H., McMahon A., Milano A., Morales J.. et al. (2017) The new NHGRI-EBI Catalog of published genome-wide association studies (GWAS Catalog). Nucleic Acids Res., 45, D896–D901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hani E.H., Boutin P., Durand E., Inoue H., Permutt M.A., Velho G., Froguel P. (1998) Missense mutations in the pancreatic islet beta cell inwardly rectifying K+ channel gene (KIR6.2/BIR): a meta-analysis suggests a role in the polygenic basis of Type II diabetes mellitus in Caucasians. Diabetologia, 41, 1511–1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Altshuler D., Hirschhorn J.N., Klannemark M., Lindgren C.M., Vohl M.C., Nemesh J., Lane C.R., Schaffner S.F., Bolk S., Brewer C.. et al. (2000) The common PPARgamma Pro12Ala polymorphism is associated with decreased risk of type 2 diabetes. Nat. Genet., 26, 76–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grant S.F., Thorleifsson G., Reynisdottir I., Benediktsson R., Manolescu A., Sainz J., Helgason A., Stefansson H., Emilsson V., Helgadottir A.. et al. (2006) Variant of transcription factor 7-like 2 (TCF7L2) gene confers risk of type 2 diabetes. Nat. Genet., 38, 320–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Scott R.A., Scott L.J., Magi R., Marullo L., Gaulton K.J., Kaakinen M., Pervjakova N., Pers T.H., Johnson A.D., Eicher J.D.. et al. (2017) An expanded genome-wide association study of Type 2 diabetes in Europeans. Diabetes, doi: 10.2337/db16-1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fuchsberger C., Flannick J., Teslovich T.M., Mahajan A., Agarwala V., Gaulton K.J., Ma C., Fontanillas P., Moutsianas L., McCarthy D.J.. et al. (2016) The genetic architecture of type 2 diabetes. Nature, 536, 41–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Faerch K., Witte D.R., Tabak A.G., Perreault L., Herder C., Brunner E.J., Kivimaki M., Vistisen D. (2013) Trajectories of cardiometabolic risk factors before diagnosis of three subtypes of type 2 diabetes: a post-hoc analysis of the longitudinal Whitehall II cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol., 1, 43–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Decode Study Group, t.E.D.E.G. (2001) Glucose tolerance and cardiovascular mortality: comparison of fasting and 2-hour diagnostic criteria. Arch. Intern. Med., 161, 397–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Farmer A. (2012) Use of HbA1c in the diagnosis of diabetes. BMJ, 345, e7293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Khaw K.T., Wareham N., Bingham S., Luben R., Welch A., Day N. (2004) Association of hemoglobin A1c with cardiovascular disease and mortality in adults: the European prospective investigation into cancer in Norfolk. Ann. Intern. Med., 141, 413–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Matthews D.R., Hosker J.P., Rudenski A.S., Naylor B.A., Treacher D.F., Turner R.C. (1985) Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia, 28, 412–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lotta L.A., Gulati P., Day F.R., Payne F., Ongen H., van de Bunt M., Gaulton K.J., Eicher J.D., Sharp S.J., Luan J.. et al. (2017) Integrative genomic analysis implicates limited peripheral adipose storage capacity in the pathogenesis of human insulin resistance. Nat. Genet., 49, 17–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Roder M.E., Porte D. Jr., Schwartz R.S., Kahn S.E. (1998) Disproportionately elevated proinsulin levels reflect the degree of impaired B cell secretory capacity in patients with noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab., 83, 604–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Weedon M.N., Clark V.J., Qian Y., Ben-Shlomo Y., Timpson N., Ebrahim S., Lawlor D.A., Pembrey M.E., Ring S., Wilkin T.J.. et al. (2006) A common haplotype of the glucokinase gene alters fasting glucose and birth weight: association in six studies and population-genetics analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet, 79, 991–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bouatia-Naji N., Rocheleau G., Van Lommel L., Lemaire K., Schuit F., Cavalcanti-Proenca C., Marchand M., Hartikainen A.L., Sovio U., De Graeve F.. et al. (2008) A polymorphism within the G6PC2 gene is associated with fasting plasma glucose levels. Science, 320, 1085–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen W.M., Erdos M.R., Jackson A.U., Saxena R., Sanna S., Silver K.D., Timpson N.J., Hansen T., Orru M., Grazia Piras M.. et al. (2008) Variations in the G6PC2/ABCB11 genomic region are associated with fasting glucose levels. J. Clin. Invest., 118, 2620–2628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Scott L.J., Mohlke K.L., Bonnycastle L.L., Willer C.J., Li Y., Duren W.L., Erdos M.R., Stringham H.M., Chines P.S., Jackson A.U.. et al. (2007) A genome-wide association study of type 2 diabetes in Finns detects multiple susceptibility variants. Science, 316, 1341–1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Orho-Melander M., Melander O., Guiducci C., Perez-Martinez P., Corella D., Roos C., Tewhey R., Rieder M.J., Hall J., Abecasis G.. et al. (2008) Common missense variant in the glucokinase regulatory protein gene is associated with increased plasma triglyceride and C-reactive protein but lower fasting glucose concentrations. Diabetes, 57, 3112–3121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vaxillaire M., Cavalcanti-Proenca C., Dechaume A., Tichet J., Marre M., Balkau B., Froguel P., Group D.S. (2008) The common P446L polymorphism in GCKR inversely modulates fasting glucose and triglyceride levels and reduces type 2 diabetes risk in the DESIR prospective general French population. Diabetes, 57, 2253–2257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Voight B.F., Kang H.M., Ding J., Palmer C.D., Sidore C., Chines P.S., Burtt N.P., Fuchsberger C., Li Y., Erdmann J.. et al. (2012) The metabochip, a custom genotyping array for genetic studies of metabolic, cardiovascular, and anthropometric traits. PLoS Genet., 8, e1002793.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Scott R.A., Lagou V., Welch R.P., Wheeler E., Montasser M.E., Luan J., Magi R., Strawbridge R.J., Rehnberg E., Gustafsson S.. et al. (2012) Large-scale association analyses identify new loci influencing glycemic traits and provide insight into the underlying biological pathways. Nat. Genet., 44, 991–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wheeler E., Leong A., Liu C.-T., Hivert M.-F., Strawbridge R.J., Podmore C., Li M., Yao J., Sim X., Hong J.. et al. (Submitted) Impact of Common Genetic Determinants of Hemoglobin A1c on Type 2 Diabetes Risk and Diagnosis in Ancestrally Diverse Populations: A Transethnic Genome-Wide Meta-Analysis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24. Strawbridge R.J., Dupuis J., Prokopenko I., Barker A., Ahlqvist E., Rybin D., Petrie J.R., Travers M.E., Bouatia-Naji N., Dimas A.S.. et al. (2011) Genome-wide association identifies nine common variants associated with fasting proinsulin levels and provides new insights into the pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes, 60, 2624–2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Knowles J.W., Xie W., Zhang Z., Chennamsetty I., Assimes T.L., Paananen J., Hansson O., Pankow J., Goodarzi M.O., Carcamo-Orive I.. et al. (2015) Identification and validation of N-acetyltransferase 2 as an insulin sensitivity gene. J. Clin. Invest., 125, 1739–1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Walford G.A., Gustafsson S., Rybin D., Stancakova A., Chen H., Liu C.T., Hong J., Jensen R.A., Rice K., Morris A.P.. et al. (2016) Genome-Wide Association Study of the Modified Stumvoll Insulin Sensitivity Index Identifies BCL2 and FAM19A2 as Novel Insulin Sensitivity Loci. Diabetes, 65, 3200–3211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ingelsson E., Langenberg C., Hivert M.F., Prokopenko I., Lyssenko V., Dupuis J., Magi R., Sharp S., Jackson A.U., Assimes T.L.. et al. (2010) Detailed physiologic characterization reveals diverse mechanisms for novel genetic Loci regulating glucose and insulin metabolism in humans. Diabetes, 59, 1266–1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Prokopenko I., Poon W., Magi R., Prasad B.R., Salehi S.A., Almgren P., Osmark P., Bouatia-Naji N., Wierup N., Fall T.. et al. (2014) A central role for GRB10 in regulation of islet function in man. PLoS Genet., 10, e1004235.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Palmer N.D., Goodarzi M.O., Langefeld C.D., Wang N., Guo X., Taylor K.D., Fingerlin T.E., Norris J.M., Buchanan T.A., Xiang A.H.. et al. (2015) Genetic variants associated with quantitative glucose homeostasis traits translate to Type 2 diabetes in Mexican Americans: The GUARDIAN (Genetics Underlying Diabetes in Hispanics) Consortium. Diabetes, 64, 1853–1866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Langenberg C., Pascoe L., Mari A., Tura A., Laakso M., Frayling T.M., Barroso I., Loos R.J., Wareham N.J., Walker M.. et al. (2009) Common genetic variation in the melatonin receptor 1B gene (MTNR1B) is associated with decreased early-phase insulin response. Diabetologia, 52, 1537–1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Manco M., Panunzi S., Macfarlane D.P., Golay A., Melander O., Konrad T., Petrie J.R., Mingrone G.. Relationship between Insulin, S. and Cardiovascular Risk, C. (2010) One-hour plasma glucose identifies insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction in individuals with normal glucose tolerance: cross-sectional data from the Relationship between Insulin Sensitivity and Cardiovascular Risk (RISC) study. Diabetes Care, 33, 2090–2097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Joshipura K.J., Andriankaja M.O., Hu F.B., Ritchie C.S. (2011) Relative utility of 1-h Oral Glucose Tolerance Test as a measure of abnormal glucose homeostasis. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract., 93, 268–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Go M.J., Hwang J.Y., Kim Y.J., Hee Oh J., Kim Y.J., Heon Kwak S., Soo Park K., Lee J., Kim B.J., Han B.G.. et al. (2013) New susceptibility loci in MYL2, C12orf51 and OAS1 associated with 1-h plasma glucose as predisposing risk factors for type 2 diabetes in the Korean population. J. Hum. Genet., 58, 362–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Genomes Project C., Auton A., Brooks L.D., Durbin R.M., Garrison E.P., Kang H.M., Korbel J.O., Marchini J.L., McCarthy S., McVean G.A.. et al. (2015) A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature, 526, 68–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Consortium U.K., Walter K., Min J.L., Huang J., Crooks L., Memari Y., McCarthy S., Perry J.R., Xu C., Futema M.. et al. (2015) The UK10K project identifies rare variants in health and disease. Nature, 526, 82–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Huang J., Howie B., McCarthy S., Memari Y., Walter K., Min J.L., Danecek P., Malerba G., Trabetti E., Zheng H.F.. et al. (2015) Improved imputation of low-frequency and rare variants using the UK10K haplotype reference panel. Nat. Commun., 6, 8111.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McCarthy S., Das S., Kretzschmar W., Delaneau O., Wood A.R., Teumer A., Kang H.M., Fuchsberger C., Danecek P., Sharp K.. et al. (2016) A reference panel of 64,976 haplotypes for genotype imputation. Nat. Genet., 48, 1279–1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Huyghe J.R., Jackson A.U., Fogarty M.P., Buchkovich M.L., Stancakova A., Stringham H.M., Sim X., Yang L., Fuchsberger C., Cederberg H.. et al. (2013) Exome array analysis identifies new loci and low-frequency variants influencing insulin processing and secretion. Nat. Genet., 45, 197–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wessel J., Chu A.Y., Willems S.M., Wang S., Yaghootkar H., Brody J.A., Dauriz M., Hivert M.F., Raghavan S., Lipovich L.. et al. (2015) Low-frequency and rare exome chip variants associate with fasting glucose and type 2 diabetes susceptibility. Nat. Commun., 6, 5897.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mahajan A., Sim X., Ng H.J., Manning A., Rivas M.A., Highland H.M., Locke A.E., Grarup N., Im H.K., Cingolani P.. et al. (2015) Identification and functional characterization of G6PC2 coding variants influencing glycemic traits define an effector transcript at the G6PC2-ABCB11 locus. PLoS Genet., 11, e1004876.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Iotchkova V., Huang J., Morris J.A., Jain D., Barbieri C., Walter K., Min J.L., Chen L., Astle W., Cocca M.. et al. (2016) Discovery and refinement of genetic loci associated with cardiometabolic risk using dense imputation maps. Nat. Genet., 48, 1303–1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zaitlen N., Pasaniuc B., Gur T., Ziv E., Halperin E. (2010) Leveraging genetic variability across populations for the identification of causal variants. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 86, 23–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ioannidis J.P., Ntzani E.E., Trikalinos T.A. (2004) ‘Racial’ differences in genetic effects for complex diseases. Nat. Genet., 36, 1312–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yang Q., Liu T., Shrader P., Yesupriya A., Chang M.H., Dowling N.F., Ned R.M., Dupuis J., Florez J.C., Khoury M.J.. et al. (2010) Racial/ethnic differences in association of fasting glucose-associated genomic loci with fasting glucose, HOMA-B, and impaired fasting glucose in the U.S. adult population. Diabetes Care, 33, 2370–2377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chen G., Bentley A., Adeyemo A., Shriner D., Zhou J., Doumatey A., Huang H., Ramos E., Erdos M., Gerry N.. et al. (2012) Genome-wide association study identifies novel loci association with fasting insulin and insulin resistance in African Americans. Hum. Mol. Genet., 21, 4530–4536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Liu C.T., Raghavan S., Maruthur N., Kabagambe E.K., Hong J., Ng M.C., Hivert M.F., Lu Y., An P., Bentley A.R.. et al. (2016) Trans-ethnic meta-analysis and functional annotation illuminates the genetic architecture of fasting glucose and insulin. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 99, 56–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kim Y.J., Go M.J., Hu C., Hong C.B., Kim Y.K., Lee J.Y., Hwang J.Y., Oh J.H., Kim D.J., Kim N.H.. et al. (2011) Large-scale genome-wide association studies in East Asians identify new genetic loci influencing metabolic traits. Nat. Genet., 43, 990–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hwang J.Y., Sim X., Wu Y., Liang J., Tabara Y., Hu C., Hara K., Tam C.H., Cai Q., Zhao Q.. et al. (2015) Genome-wide association meta-analysis identifies novel variants associated with fasting plasma glucose in East Asians. Diabetes, 64, 291–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chen P., Takeuchi F., Lee J.Y., Li H., Wu J.Y., Liang J., Long J., Tabara Y., Goodarzi M.O., Pereira M.A.. et al. (2014) Multiple nonglycemic genomic loci are newly associated with blood level of glycated hemoglobin in East Asians. Diabetes, 63, 2551–2562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chen P., Ong R.T., Tay W.T., Sim X., Ali M., Xu H., Suo C., Liu J., Chia K.S., Vithana E.. et al. (2013) A study assessing the association of glycated hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C) associated variants with HbA1C, chronic kidney disease and diabetic retinopathy in populations of Asian ancestry. PLoS One, 8, e79767.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Fesinmeyer M.D., Meigs J.B., North K.E., Schumacher F.R., Buzkova P., Franceschini N., Haessler J., Goodloe R., Spencer K.L., Voruganti V.S.. et al. (2013) Genetic variants associated with fasting glucose and insulin concentrations in an ethnically diverse population: results from the Population Architecture using Genomics and Epidemiology (PAGE) study. BMC Med. Genet., 14, 98.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ramos E., Chen G., Shriner D., Doumatey A., Gerry N.P., Herbert A., Huang H., Zhou J., Christman M.F., Adeyemo A.. et al. (2011) Replication of genome-wide association studies (GWAS) loci for fasting plasma glucose in African-Americans. Diabetologia, 54, 783–788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Liu C.T., Ng M.C., Rybin D., Adeyemo A., Bielinski S.J., Boerwinkle E., Borecki I., Cade B., Chen Y.D., Djousse L.. et al. (2012) Transferability and fine-mapping of glucose and insulin quantitative trait loci across populations: CARe, the Candidate Gene Association Resource. Diabetologia, 55, 2970–2984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rees S.D., Hydrie M.Z., O'Hare J.P., Kumar S., Shera A.S., Basit A., Barnett A.H., Kelly M.A. (2011) Effects of 16 genetic variants on fasting glucose and type 2 diabetes in South Asians: ADCY5 and GLIS3 variants may predispose to type 2 diabetes. PLoS One, 6, e24710.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Takeuchi F., Katsuya T., Chakrewarthy S., Yamamoto K., Fujioka A., Serizawa M., Fujisawa T., Nakashima E., Ohnaka K., Ikegami H.. et al. (2010) Common variants at the GCK, GCKR, G6PC2-ABCB11 and MTNR1B loci are associated with fasting glucose in two Asian populations. Diabetologia, 53, 299–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Langlois C., Abadi A., Peralta-Romero J., Alyass A., Suarez F., Gomez-Zamudio J., Burguete-Garcia A.I., Yazdi F.T., Cruz M., Meyre D. (2016) Evaluating the transferability of 15 European-derived fasting plasma glucose SNPs in Mexican children and adolescents. Sci. Rep., 6, 36202.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hatzikotoulas K., Gilly A., Zeggini E. (2014) Using population isolates in genetic association studies. Brief. Funct. Genomics, 13, 371–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Service S.K., Teslovich T.M., Fuchsberger C., Ramensky V., Yajnik P., Koboldt D.C., Larson D.E., Zhang Q., Lin L., Welch R.. et al. (2014) Re-sequencing expands our understanding of the phenotypic impact of variants at GWAS loci. PLoS Genet., 10, e1004147.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Moltke I., Grarup N., Jorgensen M.E., Bjerregaard P., Treebak J.T., Fumagalli M., Korneliussen T.S., Andersen M.A., Nielsen T.S., Krarup N.T.. et al. (2014) A common Greenlandic TBC1D4 variant confers muscle insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nature, 512, 190–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Manning A., Highland H.M., Gasser J., Sim X., Tukiainen T., Fontanillas P., Grarup N., Rivas M.A., Mahajan A., Locke A.E.. et al. (2017) A low-frequency inactivating Akt2 variant enriched in the Finnish population is associated with fasting insulin levels and Type 2 diabetes risk. Diabetes, 66, 2019–2032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Pasquali L., Gaulton K.J., Rodriguez-Segui S.A., Mularoni L., Miguel-Escalada I., Akerman I., Tena J.J., Moran I., Gomez-Marin C., van de Bunt M.. et al. (2014) Pancreatic islet enhancer clusters enriched in type 2 diabetes risk-associated variants. Nat. Genet., 46, 136–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Parker S.C., Stitzel M.L., Taylor D.L., Orozco J.M., Erdos M.R., Akiyama J.A., van Bueren K.L., Chines P.S., Narisu N., Program N.C.S.. et al. (2013) Chromatin stretch enhancer states drive cell-specific gene regulation and harbor human disease risk variants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A, 110, 17921–17926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. van de Bunt M., Manning Fox J.E., Dai X., Barrett A., Grey C., Li L., Bennett A.J., Johnson P.R., Rajotte R.V., Gaulton K.J.. et al. (2015) Transcript expression data from human islets links regulatory signals from genome-wide association studies for Type 2 diabetes and glycemic traits to their downstream effectors. PLoS Genet., 11, e1005694.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Fadista J., Vikman P., Laakso E.O., Mollet I.G., Esguerra J.L., Taneera J., Storm P., Osmark P., Ladenvall C., Prasad R.B.. et al. (2014) Global genomic and transcriptomic analysis of human pancreatic islets reveals novel genes influencing glucose metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A, 111, 13924–13929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Lyssenko V., Nagorny C.L., Erdos M.R., Wierup N., Jonsson A., Spegel P., Bugliani M., Saxena R., Fex M., Pulizzi N.. et al. (2009) Common variant in MTNR1B associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes and impaired early insulin secretion. Nat. Genet., 41, 82–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kulzer J.R., Stitzel M.L., Morken M.A., Huyghe J.R., Fuchsberger C., Kuusisto J., Laakso M., Boehnke M., Collins F.S., Mohlke K.L. (2014) A common functional regulatory variant at a type 2 diabetes locus upregulates ARAP1 expression in the pancreatic beta cell. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 94, 186–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Carrat G.R., Hu M., Nguyen-Tu M.S., Chabosseau P., Gaulton K.J., van de Bunt M., Siddiq A., Falchi M., Thurner M., Canouil M.. et al. (2017) Decreased STARD10 expression is associated with defective insulin secretion in humans and mice. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 100, 238–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Li L.C., Wang Y., Carr R., Haddad C.S., Li Z., Qian L., Oberholzer J., Maker A.V., Wang Q., Prabhakar B.S. (2014) IG20/MADD plays a critical role in glucose-induced insulin secretion. Diabetes, 63, 1612–1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Halban P.A. (1991) Structural domains and molecular lifestyles of insulin and its precursors in the pancreatic beta cell. Diabetologia, 34, 767–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Chen B.H., Hivert M.F., Peters M.J., Pilling L.C., Hogan J.D., Pham L.M., Harries L.W., Fox C.S., Bandinelli S., Dehghan A.. et al. (2016) Peripheral blood transcriptomic signatures of fasting glucose and insulin concentrations. Diabetes, 65, 3794–3804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Barroso I., Gurnell M., Crowley V.E., Agostini M., Schwabe J.W., Soos M.A., Maslen G.L., Williams T.D., Lewis H., Schafer A.J.. et al. (1999) Dominant negative mutations in human PPARgamma associated with severe insulin resistance, diabetes mellitus and hypertension. Nature, 402, 880–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Agostini M., Schoenmakers E., Mitchell C., Szatmari I., Savage D., Smith A., Rajanayagam O., Semple R., Luan J., Bath L.. et al. (2006) Non-DNA binding, dominant-negative, human PPARgamma mutations cause lipodystrophic insulin resistance. Cell Metab., 4, 303–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Majithia A.R., Flannick J., Shahinian P., Guo M., Bray M.A., Fontanillas P., Gabriel S.B., Go, T.D.C., Project, N.J.F.A.S., Consortium, S.T.D. et al. (2014) Rare variants in PPARG with decreased activity in adipocyte differentiation are associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A, 111, 13127–13132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Flannick J., Thorleifsson G., Beer N.L., Jacobs S.B., Grarup N., Burtt N.P., Mahajan A., Fuchsberger C., Atzmon G., Benediktsson R.. et al. (2014) Loss-of-function mutations in SLC30A8 protect against type 2 diabetes. Nat. Genet., 46, 357–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. McCulloch L.J., van de Bunt M., Braun M., Frayn K.N., Clark A., Gloyn A.L. (2011) GLUT2 (SLC2A2) is not the principal glucose transporter in human pancreatic beta cells: implications for understanding genetic association signals at this locus. Mol. Genet. Metab., 104, 648–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Zhou K., Yee S.W., Seiser E.L., van Leeuwen N., Tavendale R., Bennett A.J., Groves C.J., Coleman R.L., van der Heijden A.A., Beulens J.W.. et al. (2016) Variation in the glucose transporter gene SLC2A2 is associated with glycemic response to metformin. Nat. Genet., 48, 1055–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Beer N.L., Tribble N.D., McCulloch L.J., Roos C., Johnson P.R., Orho-Melander M., Gloyn A.L. (2009) The P446L variant in GCKR associated with fasting plasma glucose and triglyceride levels exerts its effect through increased glucokinase activity in liver. Hum. Mol. Genet., 18, 4081–4088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Prokopenko I., Langenberg C., Florez J.C., Saxena R., Soranzo N., Thorleifsson G., Loos R.J., Manning A.K., Jackson A.U., Aulchenko Y.. et al. (2009) Variants in MTNR1B influence fasting glucose levels. Nat. Genet., 41, 77–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Bouatia-Naji N., Bonnefond A., Cavalcanti-Proenca C., Sparso T., Holmkvist J., Marchand M., Delplanque J., Lobbens S., Rocheleau G., Durand E.. et al. (2009) A variant near MTNR1B is associated with increased fasting plasma glucose levels and type 2 diabetes risk. Nat. Genet., 41, 89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Dupuis J., Langenberg C., Prokopenko I., Saxena R., Soranzo N., Jackson A.U., Wheeler E., Glazer N.L., Bouatia-Naji N., Gloyn A.L.. et al. (2010) New genetic loci implicated in fasting glucose homeostasis and their impact on type 2 diabetes risk. Nat. Genet., 42, 105–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Renstrom F., Koivula R.W., Varga T.V., Hallmans G., Mulder H., Florez J.C., Hu F.B., Franks P.W. (2015) Season-dependent associations of circadian rhythm-regulating loci (CRY1, CRY2 and MTNR1B) and glucose homeostasis: the GLACIER Study. Diabetologia, 58, 997–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Stamenkovic J.A., Olsson A.H., Nagorny C.L., Malmgren S., Dekker-Nitert M., Ling C., Mulder H. (2012) Regulation of core clock genes in human islets. Metabolism, 61, 978–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Forrestel A.C., Miedlich S.U., Yurcheshen M., Wittlin S.D., Sellix M.T. (2017) Chronomedicine and type 2 diabetes: shining some light on melatonin. Diabetologia, 60, 808–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Mulder H. (2017) Melatonin signalling and type 2 diabetes risk: too little, too much or just right? Diabetologia, 60, 826–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Bonnefond A., Froguel P. (2017) The case for too little melatonin signalling in increased diabetes risk. Diabetologia, 60, 823–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Morris A.P., Voight B.F., Teslovich T.M., Ferreira T., Segre A.V., Steinthorsdottir V., Strawbridge R.J., Khan H., Grallert H., Mahajan A.. et al. (2012) Large-scale association analysis provides insights into the genetic architecture and pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes. Nat. Genet., 44, 981–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Dimas A.S., Lagou V., Barker A., Knowles J.W., Magi R., Hivert M.F., Benazzo A., Rybin D., Jackson A.U., Stringham H.M.. et al. (2014) Impact of type 2 diabetes susceptibility variants on quantitative glycemic traits reveals mechanistic heterogeneity. Diabetes, 63, 2158–2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Majithia A.R., Tsuda B., Agostini M., Gnanapradeepan K., Rice R., Peloso G., Patel K.A., Zhang X., Broekema M.F., Patterson N.. et al. (2016) Prospective functional classification of all possible missense variants in PPARG. Nat. Genet., 48, 1570–1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Saxena R., Hivert M.F., Langenberg C., Tanaka T., Pankow J.S., Vollenweider P., Lyssenko V., Bouatia-Naji N., Dupuis J., Jackson A.U.. et al. (2010) Genetic variation in GIPR influences the glucose and insulin responses to an oral glucose challenge. Nat. Genet., 42, 142–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Soranzo N., Sanna S., Wheeler E., Gieger C., Radke D., Dupuis J., Bouatia-Naji N., Langenberg C., Prokopenko I., Stolerman E.. et al. (2010) Common variants at 10 genomic loci influence hemoglobin A(1)(C) levels via glycemic and nonglycemic pathways. Diabetes, 59, 3229–3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Ryu J., Lee C. (2012) Association of glycosylated hemoglobin with the gene encoding CDKAL1 in the Korean Association Resource (KARE) study. Hum. Mutat., 33, 655–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Manning A.K., Hivert M.F., Scott R.A., Grimsby J.L., Bouatia-Naji N., Chen H., Rybin D., Liu C.T., Bielak L.F., Prokopenko I.. et al. (2012) A genome-wide approach accounting for body mass index identifies genetic variants influencing fasting glycemic traits and insulin resistance. Nat. Genet., 44, 659–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Horikoshi M., Mgi R., van de Bunt M., Surakka I., Sarin A.P., Mahajan A., Marullo L., Thorleifsson G., Hgg S., Hottenga J.J.. et al. (2015) Discovery and fine-mapping of glycaemic and obesity-related trait loci using high-density imputation. PLoS Genet., 11, e1005230.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Pare G., Chasman D.I., Parker A.N., Nathan D.M., Miletich J.P., Zee R.Y., Ridker P.M. (2008) Novel association of HK1 with glycated hemoglobin in a non-diabetic population: a genome-wide evaluation of 14,618 participants in the Women's Genome Health Study. PLoS Genet., 4, e1000312.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Franklin C.S., Aulchenko Y.S., Huffman J.E., Vitart V., Hayward C., Polasek O., Knott S., Zgaga L., Zemunik T., Rudan I.. et al. (2010) The TCF7L2 diabetes risk variant is associated with HbA(1)(C) levels: a genome-wide association meta-analysis. Ann. Hum. Genet., 74, 471–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]