Abstract

Vascular malformations are classified primarily according to their flow characteristics, slow flow (lymphatic and venous) or fast flow (arteriovenous). They can occur anywhere in the body but have a unique presentation when affecting the female pelvis. With a detailed clinical history and the proper imaging studies, the correct diagnosis can be made and the best treatment can be initiated. Lymphatic and venous malformations are often treated with sclerotherapy while arteriovenous malformations usually require embolization. At times, surgical intervention of vascular malformations or medical management of lymphatic malformations has been implemented in a multidisciplinary approach to patient care. This review presents an overview of vascular malformations of the female pelvis, their clinical course, diagnostic studies, and treatment options.

Keywords: interventional radiology, vascular malformation, sclerotherapy, venous malformation, lymphatic malformation, arteriovenous malformation

Objectives : Upon completion of this article, the reader will be able to diagnose and categorize malformations based on the initial presentation, clinical course, and imaging characteristics and discuss treatment options.

Accreditation : This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the accreditation requirements and policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) through the joint providership of Tufts University School of Medicine (TUSM) and Thieme Medical Publishers, New York. TUSM is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Credit : Tufts University School of Medicine designates this journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit ™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Vascular Malformations

Vascular malformations can occur anywhere throughout the body. They are best classified by their flow characteristics as Mulliken and Glowacki initially described in 1982. 1 In 1996, their system was adopted and modified by the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (ISSVA). It was updated in 2014 with additional information regarding clinical presentations, types of vessel involvement (capillary, lymphatic, venous, arteriovenous, or mixed), and the extent of involvement and genetic origins. 2 3

Slow-Flow Vascular Malformations

Lymphatic Malformations

Slow-flow malformations can be further divided into lymphatic and venous malformations (VMs). Lymphatic malformations (LMs) often present as a soft-tissue swelling that may be focal or diffuse in nature. They have a predilection for the head and neck region but can occur anywhere. LMs are formed at birth but can show rapid changes in size from a variety of factors. They can increase in size secondary to infection of either the malformation itself, from a systemic response such as an upper respiratory infection where overall lymphatic production is increased, or from trauma resulting in hemorrhage into the LM. They usually do not have overlying skin discoloration but may have a bluish hue if there is hemorrhage. Superficial vesicles or an accompanying capillary stain may be present. 4 5 6 These superficial vesicles can leak blood or chyle and sometimes serve as a lead point for infection of the entire LM. 4 7

Imaging Lymphatic Malformations

Imaging of LMs includes ultrasound that shows anechoic or hypoechoic cystic structures. While no flow is seen within the cyst itself, color Doppler analysis of the fibrous septae composing the walls may show tiny vessels that can rupture and result in rapid growth due to hemorrhage. Debris or fluid-fluid levels may be seen as a result of infection or hemorrhage. LMs are often trans-spatial crossing into different anatomic compartments and large malformations can cause mass effect on adjacent structures. The malformation fluid may contain debris representing evolving blood products. LMs can be subdivided into macrocysts, microcysts, or combined lesions based on size criteria. 4 5 6 8 Macrocysts are larger than 2 cm in diameter and tend to be more responsive to sclerotherapy treatment. Microcysts measure less than 2 cm, are more difficult to treat using sclerotherapy, and have a higher rate of recurrence. 4

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is also useful to diagnose an LM and to define the extent of the lesion. T2-weighted images show fluid-filled cystic structures, while T1 imaging can yield information about the protein content of the fluid. Contrast administration can show peripheral vascularity and confirm the absence of central enhancement differentiating it from an enhancing VM. 4 6 Dynamic MR angiography (MRA) can help establish if there is an additional venous or arterial component. 6 8

Treatment

The mainstay of treatment for LMs is percutaneous sclerotherapy where a liquid sclerosant is injected directly into the LM using both ultrasound and fluoroscopic guidance. Doxycycline is very commonly used for its availability and effectiveness. Additional sclerosants such as bleomycin, ethanol, OK-432 (picibanil), and sodium tetradecyl sulfate have also been used as a single agent or as a combination for treatment. The sclerosant irritates the lining of these LMs which then allows the LM walls to heal together after treatment. This subsequently scars down the cystic cavity and prevents it from distending with lymphatic fluid. Macrocysts tend to respond well to sclerotherapy, but microcysts have a more unpredictable outcome. Cutaneous vesicles can be treated with superficial laser ablation to help slow down any leakage and decrease the potential for infection; however, the vesicles tend to recur. Surgical resection is often not the first line of treatment for LMs and may be considered if sclerotherapy has proven unsuccessful. 4 5 9 Sirolimus is an oral immunosuppressive agent and mTOR inhibitor (mammalian target of rapamycin) that has shown promising success with decreasing lymphatic production in extensive complex LMs. 9 10 11

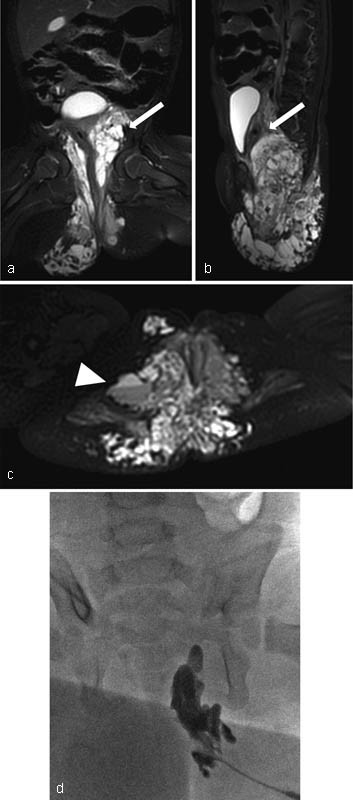

See Fig. 1 for an example of a LM.

Fig. 1.

Pelvic lymphatic malformation (PLM). ( a–c ) Coronal, sagittal and axial T2-weighted MR images. Arrows point to the diffuse macro- and microcystic lymphatic malformation of the buttocks with extension into the pelvis adjacent to the bladder. Arrowhead shows a fluid-fluid level within a larger cyst as a result of infection and/or hemorrhage. ( d ) Percutaneous sclerotherapy of the lymphatic malformation with doxycycline. The point of access is at the buttocks and the lymphatic malformation communicates with deeper components within the pelvis resulting in a larger intrapelvic treatment via a percutaneous approach.

Venous Malformations

Venous malformations are another slow-flow vascular malformation that can occur anywhere in the body. They are present at birth and grow proportionally with the child; however, they can show rapid growth or enlargement during puberty due to increased hormones. Additional causes for accelerated enlargement may be infection, trauma, or thrombosis. 12 When superficial, they appear as compressible masses often with a bluish discoloration of the skin that may enlarge in dependent areas. They do not exhibit skin temperature changes, thrill or bruit. If deeper within the soft tissues or bone, they may not be apparent until later in life. They can be focal or very extensive and at times can involve entire limbs. The majority of VMs occur sporadically; however, there are some that can be traced to a familial inheritance pattern such as blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome. 13 VMs have been linked to a somatic mutation in the TIE-2 gene, responsible for endothelial cell smooth muscle development and regulating angiogenesis and vessel stability. This mutation allows the VM to have increased distension with subsequent enlargement. 4 14 15 The genetic abnormality has been linked to inherited forms of VMs and up to half of sporadic VMs. 14 16

VMs can develop in the pelvis and rectum. A common site in women is the perineum, particularly the labia majora where it may appear as a bluish discolored swelling slowly growing over time. 17 The vulvar VM can swell and the patient may have pain, difficulty walking, or exercising which can worsen during pregnancy or menses. The visible malformation along the labia may be a small portion of a much larger VM that can involve the perineum, buttocks, and lower extremities and warrants further imaging evaluation. 4 17 If the VM involves the cervicovaginal region, the patient may present with abnormal vaginal bleeding. 12 18 19 VMs of the uterus and ovaries may be secondary to an insufficient ovarian vein resulting in pelvic congestion syndrome. 20 VMs of the urinary tract can cause hematuria, while VMs of the rectum can present with potentially life-threatening rectal bleeding. Patients with rectal VMs may develop thrombosis within the hemorrhoidal, mesenteric, or portal veins, which can lead to portal vein thromboembolism and possible hepatic infarction. 21 22 23 When the VM extends into the entire lower extremity, overgrowth, swelling, hemarthrosis, and possible pulmonary embolism can occur. 24 It is possible for a localized intravascular coagulopathy to develop in large VMs that may lead to disseminated intravascular coagulation if the patient undergoes a surgical or interventional procedure. These patients may require periprocedural anticoagulation to avoid complications. 14 24

Imaging

Initial evaluation of a VM includes ultrasound imaging. On grayscale imaging, VMs may appear as a sponge-like collection of vascular spaces or a network of slow moving compressible vascular channels. VMs can exhibit a heterogeneous hypoechoic echotexture, but this can be variable. It is possible to see thrombus or shadowing phleboliths within the lesion. On color Doppler imaging, the majority of cases have a monophasic venous waveform; however, it is common to not detect a waveform because of the sluggish flow. 25

MRI is useful to define the extent of the lesion, which may infiltrate through underlying tissue planes and muscles for a much larger area. VMs are usually isointense or hypointense on T1-weighted imaging with focal areas of decreased signal from phleboliths. The extent of the lesion is best determined on T2-weighted sequences where they are very bright due to their slow flow. Hypointense areas on T2 images or gradient echo T2* may be secondary to thrombus or phleboliths. Fluid-fluid levels are sometimes seen if there has been hemorrhage. VMs enhance on MRI with some variation in the timing of enhancement. 25

Treatment

If the VM involves primarily a limb, graded compression garments can be utilized to decrease swelling and pain from venous insufficiency. For VMs with extension into the pelvis, sclerotherapy is often the first line for treatment. Multiple sclerosants such as sodium tetradecyl sulfate, ethanol, and bleomycin have been used. A needle is inserted percutaneously into the VM and contrast is injected first to evaluate for any significant drainage into the deep venous system. If no drainage is seen, sclerosant may be injected safely. If there is drainage into the deep venous system, sclerosant injection may still be performed but with care to immediately cease injection if sclerosant reaches the deep venous system. Occasionally, occluding the venous drainage with a plug or coil can optimize treatment by increasing the contact time of the sclerosant with the endothelial lining of the VM and preventing the sclerosant from entering the deep venous system. Liquid embolic agents such as Onyx (ethylene-vinyl alcohol copolymer; Covidien, Plymouth, MN) and liquid adhesive agents/glue (e.g., isobutyl cyanoacrylate or n-butyl cyanoacrylate [n-BCA] have also been used to stop rapid venous outflow. 4 7

For long channel-like VMs, endovenous laser therapy can be used to directly ablate the vein along its length. Surgery may be an option to debulk or contour some lesions, but this is often palliative and the VM can recur. Rectal VMs may be treated surgically or endoscopically with laser ablation or sclerotherapy. 4 7 18 22 26

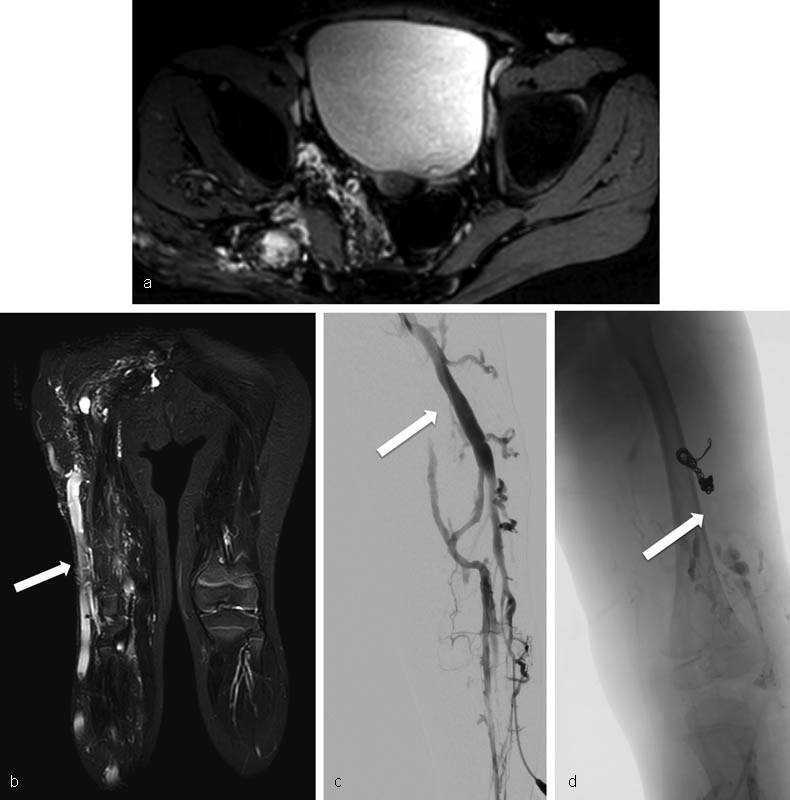

See Fig. 2 for an example of a VM.

Fig. 2.

Pelvic venous malformation (PVM). ( a ) MRI images show extensive venous malformation of the right lower extremity extending into the pelvis and alongside the bladder, uterus, and rectum. ( b ) The capacious vein along the lateral aspect of the right lower extremity (arrow) is the lateral marginal vein, a pathognomonic finding in patients with Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome. ( c ) Arrow points to the lateral marginal vein at time of treatment. Preembolization digital subtraction images demonstrate a relatively straight lateral marginal vein with multiple abnormal tributaries along the lateral aspect of the right thigh. ( d ) Treatment involved coil embolization of the lateral marginal vein at its drainage point into the femoral vein followed by endovenous laser ablation of the remainder of the vein. Posttreatment venogram shows no further filling of the lateral marginal vein (arrow).

Fast-Flow Malformations

Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are a form of fast-flow vascular malformations that can occur in the pelvis. The patient can present with pain, hematuria, abnormal vaginal, or rectal bleeding depending on which organs are involved and the AVM can erode into adjacent structures. The bleeding can either be chronic or sudden and life threatening in nature. 27 28 Pelvic AVMs may cause such increased blood flow that patients develop cardiac volume overload and congestive heart failure. Rarely patients may present with intra-abdominal hemorrhage. 28 29 30 Patients may also report a history of infertility or spontaneous abortion. On examination, AVMs can be pulsatile with a thrill and be warmer than the surrounding tissue. 31

AVMs can be congenital or acquired. Congenital AVMs develop from embryologic vessels and have abnormal connections between pelvic arteries and veins without an intervening capillary bed. They are distinguished by having multiple feeding vessels. Acquired AVMs on the other hand are abnormal connections between uterine arteries and myometrial veins and often have few or one feeding vessel. Usually, there is an iatrogenic cause such as prior cesarean section or dilation and curettage. Most patients are reproductive age women with a history of spontaneous abortion, gestational trophoblastic disease, or infection. 32 33 34 35

Most AVMs have no familial association, but a few mutations have been examined including phosphatase and tensin (PTEN) in Bannayan–Riley–Ruvalcaba or Cowden syndrome. 36 RASA-1 mutation has been identified in Parkes-Weber and capillary malformation-arteriovenous malformation (CM-AVM). 37 38 ALK-1 and endoglin abnormalities are associated with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT). 39 40

Imaging

Initial evaluation for an AVM includes ultrasound; grayscale imaging shows multiple tubular anechoic channels without an associated mass. Color Doppler studies demonstrate these channels to have a mosaic turbulent appearance with high velocity and low impedance. A negative B-HCG should distinguish these findings from abnormal placentation or gestational trophoblastic disease. 29 32 35 41 42 43 CT angiography (CTA) or MRI may be performed to identify the extent of the lesion. CTA and MRA help identify the arterial feeders and venous drainage as well as the absence of an associated mass. 29 31 CTA has an associated ionizing radiation dose but in emergent cases will rapidly provide valuable information. MRI/MRA is often preferred but takes longer to perform than CTA and sedation may be required in young pediatric patients. MRI can show multiple flow voids and signal changes indicating any adjacent fibrofatty overgrowth of the AVM. Osseous involvement can be seen as lytic changes and limb overgrowth with abnormal signal in the bone. The gold standard for AVM imaging is catheter angiography, but this is often reserved until treatment is administered in the same setting. 32 Direct intra-arterial MRA has also been proposed as a new technique to detect small feeding vessels for pelvic AVMs that may not be apparent on MR angiography or digital subtraction angiography alone. 44

Treatment

Several studies have shown that conservative treatment of acquired uterine AVMs using either hormonal treatment or noninvasive monitoring for spontaneous regression is a feasible option for asymptomatic women. 45 46 However, when a patient presents with hemorrhage, intervention may be required. An AVM should be approached first with angiograms to identify the feeding vessels and drainage veins. N-butyl cyanoacrylate or ethylene-vinyl alcohol copolymers may be administered via a transcatheter arterial approach to fill the nidus. Treating the entire nidus may necessitate accessing several branches that supply the AVM and can require multiple treatments. It is important to occlude as many branches as possible since once one branch is blocked, another branch may be recruited to continue feeding the AVM. 31 33 47 48 Gelfoam and polyvinyl alcohol particles have also been used in centers for transarterial embolization as well as sclerotherapy to obliterate the AVM. 34 41 49 50 Efficacy of one embolic agent compared with another has yet to be studied. 51 If there is a large venous outflow, it may be beneficial to also approach the AVM from the venous side to occlude the drainage with a coil, plug device, glue, or ethanol. This allows better flow control of the AVM for administration of liquid embolic agents from the arterial side or ethanol sclerotherapy to ablate the AVM. 31 50 Choi et al described using a stent graft in the external iliac vein to occlude venous outflow of the AVM while maintaining the normal venous drainage of the lower extremity for more optimal control of concurrent intra-arterial sclerosant administration and decrease in leg swelling. 49

Embolization alone is sufficient to stop the symptoms of the AVM in most cases or it may be used preoperatively to decrease blood loss during surgical resection. Some women with uterine AVM may prefer embolization to preserve fertility when feasible, but ultimately some women do require hysterectomy to have complete resolution. 29 34 52 53 One center reported a unique case of using a bovine pericardial patch to tamponade an eroding unresectable congenital pelvic AVM after failing multiple embolization attempts. 28 Another center described intraoperative transvenous embolization with a variety of occlusive agents including bone wax to aid in complete surgical resection of complex congenital AVMs. 54 Percutaneous and transvaginal embolization by direct puncture of the AVM has also been described, but these novel methods have been reserved for certain clinical scenarios. 50 55

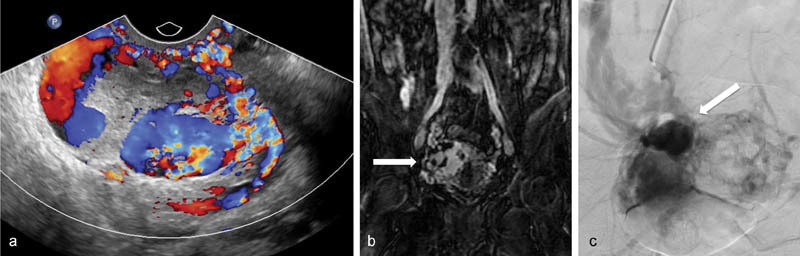

See Fig. 3 for an example of an AVM.

Fig. 3.

Pelvic arteriovenous malformation (PAVM). ( a ) Color Doppler images show markedly increased vascularity of the uterus. There is a larger ovoid area within the uterus with multidirectional flow concerning for a uterine arteriovenous malformation. ( b ) Coronal MR images of the pelvis shows a large tangle of vessels (arrow) in the pelvis as well as rapid opacification of the internal iliac vein, common iliac vein, and inferior vena cava suggesting arteriovenous malformation. ( c ) Digital subtraction angiography from the right uterine artery illustrates the abnormal collection of arterial vessels with rapid drainage into the ipsilateral internal iliac vein. The arrow demonstrates the nidus of the arteriovenous malformation.

Combined Vascular Malformations

There are syndromes that have extensive vascular malformations involving an entire lower limb with extension into the ipsilateral pelvis that can be categorized into low-flow or fast-flow malformations. The most common of the slow-flow type is Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome (KTS), which is characterized by a cutaneous capillary stain, limb overgrowth, and extensive abnormal slow-flow malformations (lymphatic or venous). The lymphatic abnormality can present as small lymphatic vesicles within the capillary stain or as larger microcysts or macrocysts within the pelvis. 56 The venous component of syndrome often has persistent embryonic veins (PEV). PEV can be subdivided into the lateral marginal vein, which runs in the superficial lateral compartment of the leg, or the persistent sciatic vein, which courses along the sciatic nerve in the posterior compartment and is considered a deep vein. 56 57 PEVs drain centrally via a network of veins connected to the deep veins of the pelvis and may provide a pathway for a pulmonary thromboembolism if they were to become thrombosed. The normal venous system for the affected limb is often rudimentary or interrupted and may have poor function that can be seen on noninvasive imaging. 57 If the VM is extensive, the patients may present with limb swelling, stasis dermatitis/cellulitis, as well as bleeding from the rectum or vagina.

Parkes-Weber on the other hand is characterized by its fast-flow component consisting primarily of small vessel AVMs as well as an extensive cutaneous capillary malformation and limb hypertrophy. These patients can present with leg length discrepancy, cardiac overload, and skin breakdown. A small lymphatic component may be involved that can present as vesicles which can leak chyle and serve as a pathway for infection. 4 38

Imaging

Radiographs of the affected limb may show phleboliths indicating underlying venous stasis or a malformation. Radiographs of both lower extremities should be performed to establish any limb length discrepancies. Ultrasound can give information about the flow characteristics of the malformation and also identify portions of the deep venous system. MRI has proven to be essential to evaluate the extent of the malformation from the lower extremity into the pelvis while MRA can also help determine slow-flow from fast-flow components. Direct angiography may be necessary to further define the vascular anomalies of the condition as well. 58

Treatment

In Klippel–Trenaunay, conservative treatment of extensive venous anomalies includes graded compression garments as well as physical therapy to help maintain joint mobility and avoid muscle contractures. Serial sclerotherapy can be performed to alleviate areas of pain and venous insufficiency or to treat the lymphatic component of the malformation. PEVs can be treated with endovenous laser and can be used to directly ablate the vein along its length or surgical ligation excision. 57 59 A PEV may provide significant drainage of the affected lower extremity if there is a poorly developed deep venous system and therefore should be carefully evaluated before ablating or ligating. 57 If intra-articular involvement is identified, collaboration with an orthopedic surgeon for resection including possible perioperative embolization may be beneficial for joint preservation. In Parkes-Weber, the AVM component can be managed similar to other AVMs with embolization of the venous outflow and occlusion or sclerotherapy of the nidus if it is amenable to treatment. 31 Given the many body systems involved with these complex combined syndromes, referral to a multidisciplinary center specialized for the treatment of vascular anomalies may be necessary for optimal care.

Summary

Vascular malformations of the female pelvis is a broad field involving both slow-flow and fast-flow malformations. Imaging plays a critical role in determining the characteristics and extent of the malformation. The cornerstone of treatment remains sclerotherapy and endovascular therapy as well as a multidisciplinary approach to patient care for complex cases.

References

- 1.Mulliken J B, Glowacki J. Hemangiomas and vascular malformations in infants and children: a classification based on endothelial characteristics. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982;69(03):412–422. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198203000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wassef M, Blei F, Adams D et al. Vascular anomalies classification: recommendations from the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies. Pediatrics. 2015;136(01):e203–e214. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dasgupta R, Fishman S J. ISSVA classification. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2014;23(04):158–161. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2014.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burrows P E. Vascular malformations involving the female pelvis. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2008;25(04):347–360. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1102993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christenson B M, Gipson M G, Smith M T. Pelvic vascular malformations. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2013;30(04):364–371. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1359730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.White C L, Olivieri B, Restrepo R, McKeon B, Karakas S P, Lee E Y. Low-flow vascular malformation pitfalls: from clinical examination to practical imaging evaluation—Part 1, Lymphatic malformation mimickers. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2016;206(05):940–951. doi: 10.2214/AJR.15.15793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pimpalwar S. Vascular malformations: approach by an interventional radiologist. Semin Plast Surg. 2014;28(02):91–103. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1376262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Francavilla M L, White C L, Oliveri B, Lee E Y, Restrepo R. Intraabdominal lymphatic malformations: pearls and pitfalls of diagnosis and differential diagnoses in pediatric patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2017;208(03):637–649. doi: 10.2214/AJR.16.17008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams D M, Trenor C C, III, Hammill A M et al. Efficacy and safety of sirolimus in the treatment of complicated vascular anomalies. Pediatrics. 2016;137(02):e20153257. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lackner H, Karastaneva A, Schwinger W et al. Sirolimus for the treatment of children with various complicated vascular anomalies. Eur J Pediatr. 2015;174(12):1579–1584. doi: 10.1007/s00431-015-2572-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trenor C C, III, Chaudry G. Complex lymphatic anomalies. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2014;23(04):186–190. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang S, Lang J H, Zhou H M. Venous malformations of the female lower genital tract. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;145(02):205–208. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flors L, Leiva-Salinas C, Maged I Met al. MR imaging of soft-tissue vascular malformations: diagnosis, classification, and therapy follow-up Radiographics 201131051321–1340., discussion 1340–1341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dasgupta R, Patel M. Venous malformations. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2014;23(04):198–202. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2014.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nguyen H L, Boon L M, Vikkula M. Genetics of vascular malformations. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2014;23(04):221–226. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2014.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soblet J, Limaye N, Uebelhoer M, Boon L M, Vikkula M. Variable somatic TIE2 mutations in half of sporadic venous malformations. Mol Syndromol. 2013;4(04):179–183. doi: 10.1159/000348327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naous J, Siqueira L. A vulvovaginal mass in a 16-year-old adolescent: a case report. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2016;29(01):e17–e19. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vogel A M, Alesbury J M, Burrows P E, Fishman S J. Vascular anomalies of the female external genitalia. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41(05):993–999. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.12.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Homa L D, Smorgick-Rosenbaum N, Smith Y R, Gemmete J J, Quint E H. Congenital venous lymphatic malformation as an unusual source of premenarchal vaginal bleeding. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2017;30(03):367–369. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Castenmiller P H, de Leur K, de Jong T E, van der Laan L. Clinical results after coil embolization of the ovarian vein in patients with primary and recurrent lower-limb varices with respect to vulval varices. Phlebology. 2013;28(05):234–238. doi: 10.1258/phleb.2012.011117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Servelle M, Bastin R, Loygue J et al. Hematuria and rectal bleeding in the child with Klippel and Trenaunay syndrome. Ann Surg. 1976;183(04):418–428. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197604000-00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Azizkhan R G.Life-threatening hematochezia from a rectosigmoid vascular malformation in Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome: long-term palliation using an argon laser J Pediatr Surg 199126091125–1127., discussion 1128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Azouz E M. Hematuria, rectal bleeding and pelvic phleboliths in children with the Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. Pediatr Radiol. 1983;13(02):82–88. doi: 10.1007/BF02390107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Enjolras O, Ciabrini D, Mazoyer E, Laurian C, Herbreteau D.Extensive pure venous malformations in the upper or lower limb: a review of 27 cases J Am Acad Dermatol 199736(2, Pt 1):219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olivieri B, White C L, Restrepo R, McKeon B, Karakas S P, Lee E Y. Low-flow vascular malformation pitfalls: from clinical examination to practical imaging evaluation—Part 2, Venous malformation mimickers. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2016;206(05):952–962. doi: 10.2214/AJR.15.15794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keljo D J, Yakes W F, Andersen J M, Timmons C F. Recognition and treatment of venous malformations of the rectum. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1996;23(04):442–446. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199611000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Selby S T, Haughey M. Uterine arteriovenous malformation with sudden heavy vaginal hemmorhage. West J Emerg Med. 2013;14(05):411–414. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2012.12.13025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ashley R A, Patterson D E, Bower T C, Stanson A W. Large congenital pelvic arteriovenous malformation and management options. Urology. 2006;68(01):2.03E13–2.03E15. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aslan H, Acar D K, Ekiz A et al. Sonographic features and management options of uterine arteriovenous malformation. A case report. Med Ultrason. 2015;17(04):561–563. doi: 10.11152/mu.2013.2066.174.sgh. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ore R M, Lynch D, Rumsey C. Uterine arteriovenous malformation, images, and management. Mil Med. 2015;180(01):e177–e180. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uller W, Alomari A I, Richter G T. Arteriovenous malformations. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2014;23(04):203–207. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aiyappan S K, Ranga U, Veeraiyan S. Doppler sonography and 3D CT angiography of acquired uterine arteriovenous malformations (AVMs): report of two cases. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8(02):187–189. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/6499.4056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen L K, Yang B L, Chen K C, Tsai Y L. Successful transarterial embolization of uterine arteriovenous malformation: report of three cases. Iran J Radiol. 2016;13(01):e15358. doi: 10.5812/iranjradiol.15358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen Y, Wang G, Xie F, Wang B, Tao G, Kong B. Embolization of uterine arteriovenous malformation. Iran J Reprod Med. 2013;11(02):159–166. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cura M, Martinez N, Cura A, Dalsaso T J, Elmerhi F. Arteriovenous malformations of the uterus. Acta Radiol. 2009;50(07):823–829. doi: 10.1080/02841850903008792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pilarski R, Burt R, Kohlman W, Pho L, Shannon K M, Swisher E. Cowden syndrome and the PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome: systematic review and revised diagnostic criteria. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(21):1607–1616. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eerola I, Boon L M, Mulliken J B et al. Capillary malformation-arteriovenous malformation, a new clinical and genetic disorder caused by RASA1 mutations. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73(06):1240–1249. doi: 10.1086/379793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Revencu N, Boon L M, Dompmartin A et al. Germline mutations in RASA1 are not found in patients with Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome or capillary malformation with limb overgrowth. Mol Syndromol. 2013;4(04):173–178. doi: 10.1159/000349919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bourdeau A, Cymerman U, Paquet M E et al. Endoglin expression is reduced in normal vessels but still detectable in arteriovenous malformations of patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia type 1. Am J Pathol. 2000;156(03):911–923. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64960-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shovlin C L, Guttmacher A E, Buscarini E et al. Diagnostic criteria for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Rendu-Osler-Weber syndrome) Am J Med Genet. 2000;91(01):66–67. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(20000306)91:1<66::aid-ajmg12>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O'Brien P, Neyastani A, Buckley A R, Chang S D, Legiehn G M.Uterine arteriovenous malformations: from diagnosis to treatment J Ultrasound Med 200625111387–1392., quiz 1394–1395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marshall A, Patel M, Eghbalieh N, Weidenhaft M, Hanemann C, Neitzschman H. Radiology case of the month: diagnosis and treatment of an acquired uterine arteriovenous malformation in a 26-year-old woman presenting with vaginal bleeding. J La State Med Soc. 2015;167(04):198–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alessandrino F, Di Silverio E, Moramarco L P. Uterine arteriovenous malformation. J Ultrasound. 2013;16(01):41–44. doi: 10.1007/s40477-013-0007-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bozlar U, Norton P T, Turba U C, Hagspiel K D. Novel technique for evaluating complex pelvic arteriovenous malformations with catheter-directed subtracted MR angiography. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2007;18(07):920–923. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Timmerman D, Van den Bosch T, Peeraer K et al. Vascular malformations in the uterus: ultrasonographic diagnosis and conservative management. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2000;92(01):171–178. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(00)00443-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oride A, Kanasaki H, Miyazaki K. Disappearance of a uterine arteriovenous malformation following long-term administration of oral norgestrel/ethinyl estradiol. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014;40(06):1807–1810. doi: 10.1111/jog.12370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barral P A, Saeed-Kilani M, Tradi F et al. Transcatheter arterial embolization with ethylene vinyl alcohol copolymer (Onyx) for the treatment of hemorrhage due to uterine arteriovenous malformations. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2017;98(05):415–421. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2016.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Castaneda F, Goodwin S C, Swischuk J L et al. Treatment of pelvic arteriovenous malformations with ethylene vinyl alcohol copolymer (Onyx) J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2002;13(05):513–516. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61532-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Choi S Y, Do Y S, Lee D Y, Lee K H, Won J Y. Treatment of a pelvic arteriovenous malformation by stent graft placement combined with sclerotherapy. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51(04):1006–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Do Y S, Kim Y W, Park K B et al. Endovascular treatment combined with emboloscleorotherapy for pelvic arteriovenous malformations. J Vasc Surg. 2012;55(02):465–471. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yoon D J, Jones M, Taani J A, Buhimschi C, Dowell J D. A systematic review of acquired uterine arteriovenous malformations: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and transcatheter treatment. AJP Rep. 2016;6(01):e6–e14. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1563721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moulder J K, Garrett L A, Salazar G M, Goodman A. The role of radical surgery in the management of acquired uterine arteriovenous malformation. Case Rep Oncol. 2013;6(02):303–310. doi: 10.1159/000351609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ghai S, Rajan D K, Asch M R, Muradali D, Simons M E, TerBrugge K G. Efficacy of embolization in traumatic uterine vascular malformations. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2003;14(11):1401–1408. doi: 10.1097/01.rvi.0000096761.74047.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mallios A, Laurian C, Houbballah R, Gigou F, Marteau V. Curative treatment of pelvic arteriovenous malformation--an alternative strategy: transvenous intra-operative embolisation. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011;41(04):548–553. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2010.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lehrman E D, Heller M, Poder L, Kerlan R, Huddleston H G, Kohi M P. Transvaginal obliteration of a complex uterine arteriovenous fistula using ethylene vinyl alcohol copolymer. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2017;28(06):842–843. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2017.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baskerville P A, Ackroyd J S, Browse N L. The etiology of the Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. Ann Surg. 1985;202(05):624–627. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198511000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oduber C E, Young-Afat D A, van der Wal A C, van Steensel M A, Hennekam R C, van der Horst C M. The persistent embryonic vein in Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. Vasc Med. 2013;18(04):185–191. doi: 10.1177/1358863X13498463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ziyeh S, Spreer J, Rössler J et al. Parkes Weber or Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome? Non-invasive diagnosis with MR projection angiography. Eur Radiol. 2004;14(11):2025–2029. doi: 10.1007/s00330-004-2274-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Noel A A, Gloviczki P, Cherry K J, Jr, Rooke T W, Stanson A W, Driscoll D J. Surgical treatment of venous malformations in Klippel-Trénaunay syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 2000;32(05):840–847. doi: 10.1067/mva.2000.110343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]