Abstract

Purpose

Prescription opioid abuse is an epidemic in the United States; multimodal analgesia has been suggested as a potential solution to decrease postoperative opioid use. Our primary aim was to determine the effect of perioperative celecoxib on opioid intake. Secondary goals of the study were to determine if perioperative administration of celecoxib decreased postoperative patient-reported pain, and to determine if patient demographic characteristics could predict postoperative pain and opioid intake.

Methods

This prospective cohort study enrolled patients undergoing mass excision or carpal tunnel, trigger finger, or DeQuervain’s release by one of three fellowship-trained hand surgeons. Patients in the experimental group were given 200mg celecoxib tablets taken BID starting the day before surgery and continued for 5 days postoperatively. Both groups received hydrocodone/acetaminophen tablets 5mg/325mg PRN after surgery. Postoperatively, patients completed daily opioid consumption and pain logs for seven days and underwent a pill count. Outcomes included morphine milligram equivalents (MME) consumed and postoperative pain.

Results

123 patients were enrolled; 68 control patients and 54 celecoxib patients. Fifty (74%) and 37 (69%) patients respectively completed the study. Overall, the median number of MMEs consumed was 25 (range=0–330). During the first postoperative week, patients in the celecoxib and control groups were similar with respect to postoperative pain experienced (median VAS=2.0 vs. 1.4, respectively) and amount of opioid taken (median MMEs=30 vs. 20, respectively).

Conclusions

Patients taking perioperative celecoxib had similar postoperative pain and opioid intake compared to those patients not prescribed celecoxib in our study. Regardless of study group, five to ten hydrocodone tablets were sufficient to control postoperative pain for most patients undergoing soft-tissue ambulatory hand surgery. This may be due to the limited duration and mild nature of pain after outpatient elective hand surgery.

Keywords: Celecoxib, NSAIDs, Opioids, Postoperative Pain

Introduction

Prescription opioid use has become an epidemic in the United States as almost 2 million Americans have abused or are currently dependent on prescription opioids.1,2 More than 14,000 Americans died from overdoses involving prescription opioids in 2014 while societal costs of opioid abuse in the United States were estimated to be $55.7 billion in 2007.3 The number of deaths involving opioids have quadrupled since 2000. It is now one of the leading causes of death in adults from 25–44 years of age.4,5 Despite these alarming trends, prescriptions for opioid medications have increased almost three-fold from 1997–2013.6 Prescription opioids are also quickly becoming the primary initial drug of abuse in young adults, most of whom obtain opioids from a friend or relative with a prescription.7,8

Orthopedic surgeons prescribe 8% of all opioid prescriptions in the United States.9 Recent literature has also highlighted the concerns regarding prolonged use of postoperative opioid medications as well as the over-prescription of narcotic medications after hand surgery. A recent database study showed that 13% of previously opioid-naïve patients refilled their opioid prescriptions over three months after hand surgery.10 Rogers et al. noted, on average, patients consumed approximately 9 opioid pills after soft tissue procedures of the hand and 14 after procedures involving bone. This led to the prescription of an average of 19 excess opioid pills per patient undergoing upper extremity procedures, or almost 2000 excess pills per 100 patients undergoing these procedures.11 Kim et al corroborated these findings in over 1400 patients who consumed approximately 5 pills after minor soft tissue hand procedures or 13 to 14 pills for procedures involving bone.12 Both studies prospectively enrolled patients but relied on 2 weeks of patient recall to quantify opioid consumption.

Many surgeons and anesthesiologists are attempting to decrease postoperative opioid use through multimodal analgesia. Multiple studies have shown COX-2 inhibitors reduce postoperative pain and analgesic consumption across different surgical specialties.13,14,15,16,17 Several orthopedic studies evaluating celecoxib, a COX-2 specific NSAID, after total knee arthroplasty, meniscectomy, and a variety of surgeries involving bony manipulation, found celecoxib to reduce postoperative pain and opioid consumption.18,19,20,21 However, it is unclear if COX-2 inhibitors can reduce opioid intake following hand surgery.

The purpose of this study was to determine if perioperative administration of celecoxib decreases postoperative consumption of opioids after ambulatory soft-tissue hand surgery. We tested the null hypothesis that perioperative celecoxib use would not change the morphine equivalents consumed postoperatively. Secondary goals of the study were to determine if perioperative administration of celecoxib decreases postoperative patient-reported pain, and to determine if patient demographic characteristics predict postoperative pain level and opioid intake.

Materials and Methods

This prospective cohort study was approved by our institutional review board. The study was performed at an academic, tertiary care center. Patients were enrolled over a four-year period from 2012 to 2016. Patients at least 18 years of age undergoing DeQuervain’s release, mini open carpal tunnel release, open trigger finger release, ganglion excision, or a combination of these procedures were eligible for inclusion. These procedures were chosen for study because they are performed with little technique variation among our surgeons and it was expected that individual cases would experience similar levels of postoperative pain. Patients were enrolled prospectively at their preoperative office visit in the clinic of one of three fellowship trained hand surgeons. Those in the celecoxib group were enrolled from the clinic of *** while those in the control were enrolled from the clinics of *** and ***.

Patients with any history of adverse reaction to opioid or NSAID use, renal insufficiency, history of gastrointestinal disease, coronary artery bypass grafts, myocardial infarctions, congestive heart failure, stroke, or sulfa or salicylate hypersensitivity were excluded as they would not be able to take either celecoxib and/or opioids. Patients taking chronic pain medication (defined as daily use of any pain medication) including, but not limited to, opioids, NSAIDs, or neuropathic pain medications, or patients that took opioid medications in the previous 6 weeks were also excluded as they often have developed drug tolerances, which could confound the amount of pain medication consumed postoperatively.22,23

Patients in the celecoxib group received fourteen 200mg capsules of celecoxib (2 capsules in the morning the day before surgery, 2 capsules the morning of surgery, and then one capsule twice a day for the next 5 days) and 30 pills of 5mg/325mg hydrocodone/acetaminophen prescribed as one to two tablets pro re nata (PRN) every 4–6 hours postoperatively. Patients in the control group received 30 pills of 5mg/325mg hydrocodone/acetaminophen prescribed as one to two tablets PRN every 4–6 hours postoperatively. All procedures were performed either with Bier block with local infiltration at the end of the procedure or incisional local infiltration with sedation.

All participants underwent pre- and postoperative assessment as well as completed a 7-day postoperative pain and medication usage log. During participants’ preoperative visits, we obtained demographic data, visual analog scale (VAS) pain scores (0–10 cm line), and recorded VAS pain anchors to approximate pain tolerance (0–10 cm line asking patients how much it hurts to stub a toe and to get a paper cut). The VAS pain anchors were collected to be used as a corrective factor if significant between-group differences were noted preoperatively. On the day of surgery, patients were given a daily VAS pain log on which they recorded their average morning and evening pain along with the number of celecoxib (experimental group only) and opioid pills taken, for 7 postoperative days. At patients’ postoperative visits, pain was recorded again using VAS pain scores, patients were asked if over the counter (OTC) pain medication was used (i.e., supplementary analgesia), and we conducted a pill count to confirm the number of opioid pills taken.

Data Analysis

Rogers et al. described the average number of postoperative opioid pills consumed in outpatient hand surgery (9 opioid pills with a distribution skewed towards higher pill consumption), and from this information we conducted an a priori sample size calculation for the primary outcome measure of decreased opioid intake. Our analysis showed an enrollment of 50 patients in each group was necessary to detect a 50% reduction in opioid intake with 80% power and a two-tailed alpha of 0.05 using a Mann Whitney U test. This goal of 50 patients in each group was also sufficient for our secondary aim as 29 patients per group would be sufficient to detect a meaningful change on VAS pain scores (1.5 points, SD 2) with the same alpha and beta values.24,25,26

VAS pain and pain anchors were measured using a standard ruler on the 10-cm scale and recorded to the nearest mm (Zero = no pain; 10 = worst imaginable pain). The number of opioid pills used was calculated from the patients’ 7-day postoperative log and confirmed by a pill count at their first postoperative visit. This number was then converted to daily morphine milligram equivalent (MME) dosing (one 5/325 mg tablet of hydrocodone/acetaminophen = 5 MME). Average pain one week postoperatively was calculated by averaging all AM and PM pain measurements from patients’ postoperative logs. Statistical tests comparing the two cohorts were not reported as we did not reach our enrollment goals. Instead, we reported both groups’ descriptive statistics of postoperative opioid intake and pain scores. Mann-Whitney U tests were used to determine if opioid consumption or pain ratings differed by use of analgesia, type of surgery, or sex of the patient sample. Spearman’s rho was used to determine if patient age or pain tolerance correlated with opioid intake or postoperative pain. Two multivariable linear regression models with average week one pain and total MME opioid consumption as the dependent variables were constructed by force entry of age, sex, use of supplemental analgesia, surgery type, and pain tolerance. We performed an as-treated analysis, those patients that did not take celecoxib that were initially enrolled in the celecoxib arm were analyzed as if they were part of the control group (4 patients).

Results

A total of 122 patients were enrolled, 68 patients in the control group and 54 in the experimental group. Eight-nine percent of the patients were enrolled in the first two years of the study (5/2012–5/2014). Fifty (74%) patients in the control group and 37 (69%) patients in the experimental group completed the study. Failure to complete a postoperative opioid log was the reason for patients not completing the study. Four patients eventually were evaluated as part of the control group (did not take their prescribed celecoxib medication), leaving a total of 54 patients in the final control group and 33 patients in the final experimental group for analysis. Patient demographic information and the type of surgery completed in both the celecoxib and control arms of the study are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics, Surgery type, Pre and Postoperative Score *

| Control | Celecoxib | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recriuited | 68 | 54 | 122 | |

| Completed | 50 (74%) | 37 (69%) | 87 (71%) | |

| As Treated† | 54 (79%) | 33 (61%) | 87 (71%) | |

| Age | 54.9 (14) | 48.6 (16) | 52.5 (15) | |

| Sex (M) | 0.43 | 0.36 | 0.4 | |

| VAS preop (0–10)‡ | 3.1 (2.7) | 3.3 (2.8) | 3.2 (2.7) | |

| VAS relative pain tolerance (0–10)‡ | 4.1 (2.1) | 3.6 (1.8) | 3.9 (20.0) | |

| Supplemental Analgesia | 34 (68%) | 25 (81%) | 59 (73%) | |

|

| ||||

| Surgery Type | ||||

| CTR | 22 (41%) | 10 (30%) | 33 | |

| TF | 11 (20%) | 5 (15%) | 16 | |

| Cyst removal | 18 (33%) | 11 (33%) | 29 | |

| DQ | 0 | 1 (3%) | 1 | |

| combo | 3 (6%) | 5 (15%) | 8 | |

No differences existed between control and celecoxib cohorts (p>0.05)

Four as-treated patients from celecoxib group to control group

Mean (SD)

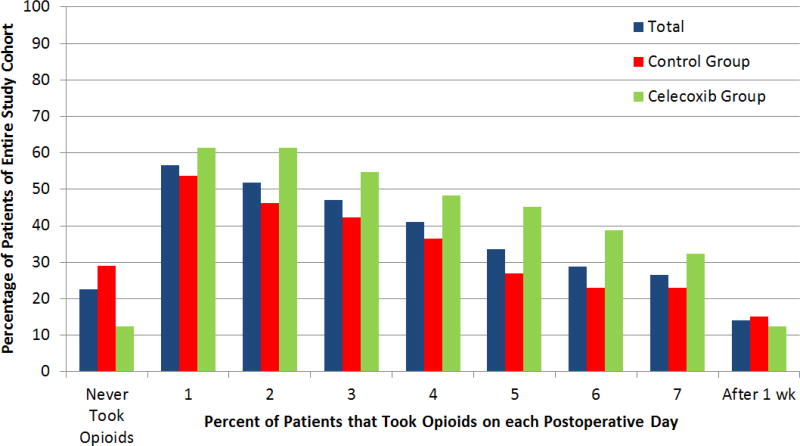

Twenty-three percent of the entire cohort did not take any postoperative opioid medication. 48% of patients were no longer taking opioid mediation after postoperative day 2 (Figure 1). Fourteen percent of patients continued to take opioid medications after the first postoperative week. The median number of MME consumed in the entire study population was 25 (range 0–330, IQR 5–83.8 MMEs), corresponding to a median of 5 hydrocodone/acetaminophen pills.

Figure 1.

Length of Opioid Use after Surgery

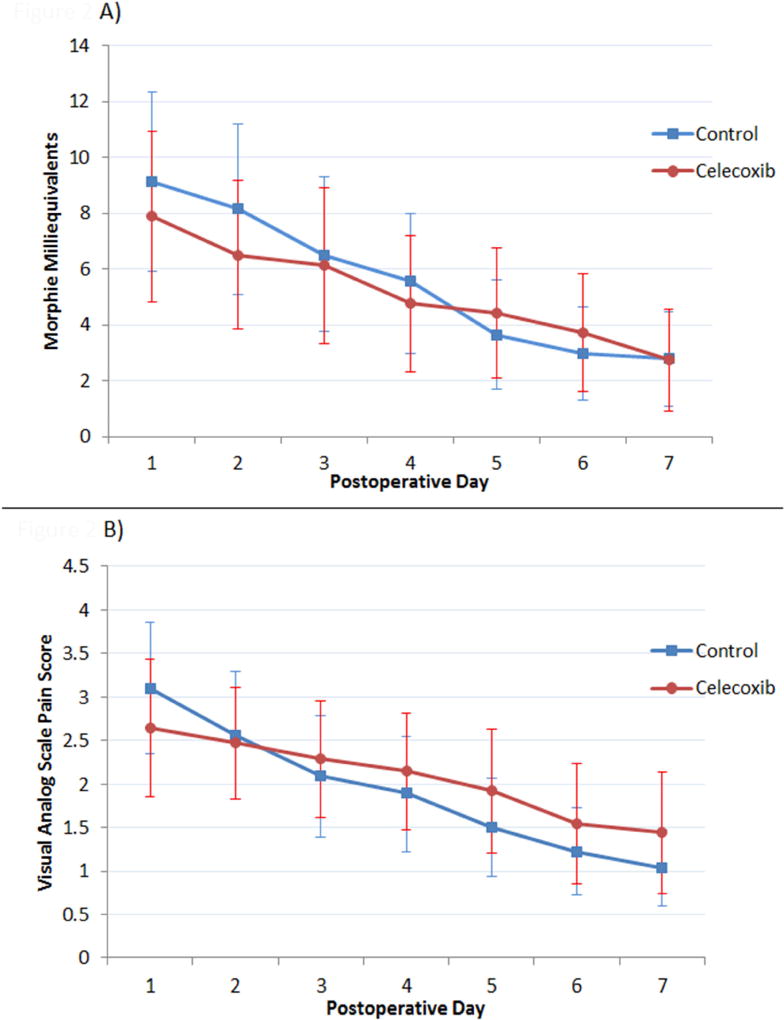

Patients’ postoperative week one pain scores and MMEs consumed are presented in Table 2. The average morphine milligram equivalents consumed and average VAS pain on each postoperative day are shown in Figure 2. Thirty percent of patients in the control group took no postoperative opioid medications vs 12.1% in the celecoxib group.

Table 2.

Celecoxib vs Experimental Group Postop Opioid Intake and Pain Scores*

| Control | Celecoxib | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Postoperative Week 1 VAS pain | 1.4 (0–7.7) | 2.0 (0–5.5) | 1.6 (0–7.7 |

| Patients Taking No Postoperative Opioids (N) | 16 (30%) | 4 (12.1%) | 20 (23%) |

| Postoperative Week 1 MME consumed | 20 (0–210) | 27.5 (0–270) | 25 (0–270) |

| Total MME Consumed | 20 (0–250) | 30 (0–330) | 25 (0–330) |

median (range)

Figure 2.

Average (A) Morphine Milligram Equivalents and (B) Visual Analog Pain Score by Postoperative Day

We combined all patient data when analyzing patient demographic factors that may predict opioid use or pain. The bivariate factors are shown in Table 3. We constructed two linear regression models with the dependent variables of total MME consumption as well as average week one pain. Increased patient age was associated with both lower postoperative pain (β= −0.53, 95%CI −0.81 to −0.25) and lower opioid consumption (β=−1.31, 95%CI −2.22 to −0.39). Consumption of supplemental analgesia correlated with higher postoperative pain (β=1.15, 95%CI 0.30 to 2.0) and increased opioid consumption (β=57.9, 95%CI 28.3 to 87.5). Lower baseline pain tolerance correlated with increased average week one pain (β=0.304, 95%CI 0.11 to 0.50) but not with increased opioid intake (β=−1.90, 95%CI −8.57 to 4.86). Neither patient sex nor surgery type was associated with postoperative pain or opioid intake.

Table 3.

Patient Demographic Data; Differences in Postoperative Pain and Opioid Use

| Postop Week 1 VAS pain | Postop Week 1 MME | Total MME | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex* | ||||

| Male | 1.5 (0–6.5) | 25 (0–180) | 30 (0–200) | |

| Female | 1.8 (0–7.7) | 25 (0–270) | 25 (0–330) | |

|

| ||||

| Surgery Type* | ||||

| CTR | 1.7 (0–7.7) | 25 (0–270) | 32.5 (0–330) | |

| TF | 1.2 (0–5.4) | 7.5 (0–80) | 7.5 (0–80) | |

| Cyst Removal | 1.8 (0–6.5) | 30 (0–170) | 30 (0–200) | |

|

| ||||

| Supplemental Analgesia* | ||||

| No | 0.5 (0–5) | 0 (0–30) | 0 (0–45) | |

| Yes | 2.3 (0.1 – 7.69) | 45 (5–270) | 55 (5–330) | |

|

| ||||

| Pain Tolerance | ||||

| Spearman's Rho | ρ = 0.175 | ρ = −0.117 | ρ = −0.069 | |

|

| ||||

| Age | ||||

| Spearman's Rho | ρ = −0.38 | ρ = −0.394 | ρ = −0.391 | |

Median (range) values provided

Discussion

Overall opioid intake was low with a median consumption of 25 morphine milligram equivalents (5 hydrocodone/acetaminophen tablets) for an average of approximately two postoperative days. Almost a quarter of the patients took no opioid medications. Patients taking perioperative celecoxib had similar postoperative pain and opioid intake compared to those patients not prescribed celecoxib in our study. There were also low patient-rated postoperative pain scores; postoperative day one pain scores were the same or less than both patients’ preoperative pain and their subjective ratings of a paper cut/stubbing toe. In addition, younger age and taking supplemental non-prescription analgesia were associated with an increase in postoperative opioid intake and pain. Lower pain tolerance correlated with increased postoperative pain but not opioid use.

Within orthopedics, there is mixed evidence for the use of celecoxib to reduce postoperative opioid intake and pain. A randomized controlled study by Huang et al. showed that patients administered perioperative celecoxib had a reduction in postoperative patient controlled analgesia of 40% compared to the control group after total knee arthroplasty (TKA).19 Ekman et al. evaluated patients after knee arthroscopy for a period of 36 hours after surgery. Patients administered celecoxib took only one less hydrocodone/acetaminophen tablet over the first 24 hours after surgery than the control group. There was no difference in opioid intake or pain scores for the remainder of the study.20 Our study found similar postoperative opioid consumption between patients taking celecoxib and patients only prescribed opioid medications. The nature of the surgeries likely has a role in the difference in findings. TKA is more invasive, involves cutting bone, and requires more extensive surgical dissection than outpatient hand surgeries considered in this study or knee arthroscopy as evaluated by Ekman et al. Potential effects of celecoxib on pain might be more effective in preventing the larger post-surgical inflammatory response after TKA.

Two previous studies evaluated total opioid use after hand surgery but relied on patient recall of consumption.11,12 The current study prospectively collected daily opioid intake, performed a pill count at patients’ postoperative visit and rated patient postoperative pain. Despite this methodologic difference, our study corroborated the use of a median of 5 hydrocodone/acetaminophen tablets (25 MME) after soft tissue hand surgery as reported by Kim et al. (5.1 pills).12 Meanwhile, Rogers et al. found that patients undergoing similar procedures took on average 9 (+/− 9) pills. The mean number of pills taken in the current study was 9.7 (+/− 11.5), however, we reported median values due to a non-normal distribution likely present in the study performed by Rogers et al.11 Similar results were obtained with regard to length of opioid use and the number of patients not taking opioid medication. When evaluating the cohorts studied by Kim et al. and Rogers et al., 28% and approximately 24% patients took no opioid pain medication, respectively (23% in the current study). Patients took opioid medications for an average of 2.2 days after undergoing soft tissue procedures in the study performed by Kim et al. Fifty-two percent of patients were no longer taking opioids after postoperative day 2 in the study performed by Rogers et al. (48% in the current study). In addition to the opioid data, the current study shows patients have little postoperative pain after these procedures, likely the reason for the low postoperative opioid intake. Overall, our study found strikingly similar results, confirming their findings of low opioid use after soft tissue hand procedures.11,12

We also evaluated patient demographic variables and their relation to postoperative opioid consumption. There was a positive association between OTC analgesic use and increased opioid use. OTC analgesia use may be a proxy of postoperative pain (i.e., the more pain experienced by patients the more likely they were to supplement their analgesic regimen with both OTC medications and more opioid pills). Our data suggesting older patients use less postoperative opioid medication are consistent with prior anesthesia literature as well as the study performed by Kim et al. Older patients have also been shown to be at decreased risk of prolonged opioid use after hand surgery.10 It is hypothesized that different pharmacokinetics or psychological approaches to pain in older patients may explain decreased consumption in opioid medication.12,27

Previous studies have shown that psychological factors such as pain catastrophizing play a role in postoperative pain and function.28,29,30,31 In our study, patients with lower pain tolerance experienced more postoperative pain, however, there was no association between opioid use and pain tolerance. This is similar to studies performed by Pavlin et al. and Khan et al. Both groups found pain catastrophizing predicted postoperative pain levels but not postoperative analgesic use.

There were several limitations inherent to our study. This study design is a cohort study rather than a placebo-controlled randomized study. We choose this design to simplify patient recruitment, however, this may have introduced systematic error (bias) into our study resulting in inconclusive results. Despite the similar practice habits of the surgeons participating in the study, we were unable to control for unforeseen differences in indications, surgical technique, or patient mix that may have confounded our results. Due to these reasons as well as inadequate sample size, we did not present a statistical comparison between groups in this study. Rather, we focused on the data and analysis obtained from the whole study cohort.

Overall, there was a long recruitment period to achieve our numbers in the study. Most patients were sequentially recruited and enrolled over the initial two years of the study when research staff was available. However, the final 14 patients were recruited over a 21-month period (6/2014–2/2016) due to unavailability of research staff to help with recruitment and follow-up. The total number of patients recruited for the study, excluded based on exclusion criteria, and patient refusal were also not recorded in this study. The lack of sequential enrollment or enumeration of patients recruited/excluded may have introduced bias as patients included in the study cohort may represent a distinct population from those who did not participate in the study.

Patients were aware of their participation in a study investigating postoperative pain and opioid use which may have affected actual opioid use and reporting. This, however, would not have created differential bias, as this would have a similar impact on both the control and celecoxib groups’ opioid intake. The somewhat low study completion rate of 71% may be attributable to the strict requirements for patients to prospectively record opioid intake and pain levels multiple times a day. We feel this could allow us to best document true opioid intake after surgery and to most accurately identify trends in opioid use and pain over the first postoperative week. Another limitation was the low VAS pain scores found after these procedures (less than the MCID), which may have limited our ability to detect a difference between the two groups.

Orthopedic surgery is among the specialties that prescribe the most prescription opioids in the United States; it is vital that they play an integral role in decreasing the public health burden of prescription opioid drug abuse.9 Despite our results, we believe that multimodal analgesia will play an important role in reducing opioids from postoperative pain regimens, however, this study shows that prescribing an additional COX-II inhibitor is unlikely to be the only solution after soft-tissue hand procedures.

Multiple studies have now shown the low numbers of opioids consumed after soft-tissue hand surgery, while 23–28% of patients take no opioids at all. Our study also describes low patient-rated pain scores after soft tissue hand procedures. Research into patient education regarding postoperative pain expectations, non-pharmaceutical pain management techniques, along with alternative non-opioid medications is needed to continue to reduce and possibly eventually eliminate postoperative opioid use after soft tissue hand procedure. Currently, the available evidence supports previously proposed recommendations that no more than 5–10 opioid pills should be prescribed for most patients after soft tissue hand procedures.

Acknowledgments

-

-

Andre Guthrie

-

-

This publication was supported by the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences grant UL1 TR000448, subaward TL1 TR000449, from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This work was also supported by a grant from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation to Washington University. Each award supports research time for the authors (J.G.S., D.A.L., and A.Z.D) as opposed to directly funding this investigation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Investigation performed at Washington University in St. Louis, Dept. Orthopedic Surgery

References

- 1.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Survey on Drug Use and Health. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prescription Opioid Overdose Data. Injury Prevention and Control: Opioid Overdose [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birnbaum HG, White AG, Schiller M, Waldman T, Cleveland JM, Roland CL. Societal Costs of Prescription Opioid Abuse, Dependence, and Misuse in the United States. Pain Med. 2011;12:657–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wide-ranging online data for epidemiologic research (WONDER) National Center for Health Statistics [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ten Leading Causes of Death and Injury. Injury Prevention and Control: Data and Statistics (WISQARS) [Google Scholar]

- 6.America’s Addiction to Opioids: Heroin and Prescription Drug Abuse. National Institute on Drug Abuse [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manchikanti L, Singh A. Therapeutic opioids: a ten-year perspective on the complexities and complications of the escalating use, abuse, and nonmedical use of opioids. Pain Physician. 2008;11:S63–S88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Volume 1: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied St; [Google Scholar]

- 9.Volkow ND, Mclellan TA, Cotto JH. Characteristics of Opioid Prescriptions in 2009. J Am Med Assoc. 2011;305(13):1229–1301. doi: 10.1002/sim2836.Editors. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson SP, Chung KC, Zhong L, et al. Risk of Prolonged Opioid Use Among Opioid-Naiive Patients Following Common Hand Surgery Procedures. J Hand Surg Am. 2016;41(10):947–957.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2016.07.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodgers J, Cunningham K, Fitzgerald K, Finnerty E. Opioid consumption following outpatient upper extremity surgery. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(4):645–650. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim N, Matzon JL, Abboudi J, et al. A Prospective Evaluation of Opioid Utilization after Upper-Extremity Surgical Procedures: Identifying Consumption Patterns and Dtermining Prescribing Guidelines. J Bone Jt Surg. 2016;89:1–9. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.15.00614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Derry S, Ra M. Single dose oral celecoxib for acute postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;14(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004233.pub3. CD004233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Straube S, Derry S, McQuay HJ, Moore Ra. Effect of preoperative Cox-II-selective NSAIDs (coxibs) on postoperative outcomes: a systematic review of randomized studies. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2005;49(5):601–613. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2005.00666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White PF, Recart A, Issioui T, et al. The Efficacy of Celecoxib Premedication on Postoperative Pain and Recovery Times After Ambulatory Surgery: A Dose-Ranging Study. Anesth Analg. 2003 Jun;:1631–1635. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000062526.60681.7B329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Issioui T, Klein KW, White PF, et al. The efficacy of premedication with celecoxib and acetaminophen in preventing pain after otolaryngologic surgery. Anesth Analg. 2002;94(5):1188–93. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200205000-00025. table of contents. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11973187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun T, Sacan O, White PF, Coleman J, Rohrich RJ, Kenkel JM. Perioperative versus postoperative celecoxib on patient outcomes after major plastic surgery procedures. Anesth Analg. 2008;106(3):950–8. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181618831. table of contents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buvanendran A, Kroin JS, Tuman KJ, et al. Effects of Perioperative Administration of a Selective Cyclooxygenase 2 Inhibitor on Pain Management and Recovery. J AM Med Assoc. 2003;290(18):2411–2418. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.18.2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang Y-M, Wang C-M, Wang C-T, Lin W-P, Horng L-C, Jiang C-C. Perioperative celecoxib administration for pain management after total knee arthroplasty - a randomized, controlled study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:77. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-9-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ekman EF, Wahba M, Ancona F. Analgesic efficacy of perioperative celecoxib in ambulatory arthroscopic knee surgery: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(6):635–642. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gimbel JS, Brugger a, Zhao W, Verburg KM, Geis GS. Efficacy and tolerability of celecoxib versus hydrocodone/acetaminophen in the treatment of pain after ambulatory orthopedic surgery in adults. Clin Ther. 2001;23(2):228–241. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(01)80005-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11293556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carroll IR, Angst MS, Clark JD. Management of Perioperative Pain in Patients Chronically Consuming Opioids. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2004;29(6):576–591. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rapp SE, Ready LB, Nessly ML. Acute pain management in patients with prior opioid consumption : a case-controlled retrospective review. Pain. 1995;61:195–201. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)00168-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee JS. Clinically Important Change in the Visual Analog Scale after Adequate Pain Control. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10(10):1128–1130. doi: 10.1197/S1069-6563(03)00372-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelly A-M. The minimum clinically significant difference in visual analogue scale pain score does not differ with severity of pain. Emerg Med J. 2001;18:205–207. doi: 10.1136/emj.18.3.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tashjian RZ, Deloach J, Porucznik Ca, Powell AP. Minimal clinically important differences (MCID) and patient acceptable symptomatic state (PASS) for visual analog scales (VAS) measuring pain in patients treated for rotator cuff disease. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2009;18(6):927–932. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2009.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woodhouse a, Mather LE. The influence of age upon opioid analgesic use in the patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) environment. Anaesthesia. 1997;52(10):949–955. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1997.216-az0350.x. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9370836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vranceanu A-M, Bachoura A, Weening A, Vrahas M, Smith RM, Ring D. Psychological factors predict disability and pain intensity after skeletal trauma. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(3):e20. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.00479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pavlin DJ, Sullivan MJL, Freund PR, Roesen K. Catastrophizing: a risk factor for postsurgical pain. Clin J Pain. 2005;21(1):83–90. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200501000-00010. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15599135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khan RS, Ahmed K, Blakeway E, et al. Catastrophizing: a predictive factor for postoperative pain. Am J Surg. 2011;201(1):122–131. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.London D, Stepan J, Boyer M, Calfee R. The Impact of Depression and Pain Catastrophization on Initial Presentation and Treatment Outcomes for Atraumatic Hand Conditions. J Bone Jt Surg. 2014;96A(10):806–814. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.M.00755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]