Abstract

Quarantine is an important, but often misused tool of public health. An effective quarantine requires a process that inspires trust in government, only punishes noncompliance and promotes a culture of social responsibility. Accomplishing successful quarantine requires incentives and enabling factors, payments, job security, and a tiered enforcement plan. In this paper, we examine the variation in state level quarantine laws and assess the effectiveness of these laws and regulations. We find that most states allow for an individual to have a hearing (63%) and to have a voice in burial and cremation procedures (71%), yet are weak on all other individual rights measures. Only 20% of states have provisions to protect employment when an individual is under quarantine, and less than half have plans for safe and humane quarantines. Decision makers at the state and local level must make a concerted effort to revise and update quarantine laws and regulations. Ideally, these laws and regulations should be harmonized so as to avoid confusion and disruption between states, and public health officials should work with populations to identify and address the factors that will support successful quarantines if they are ever required.

INTRODUCTION

Quarantine, the separation and restriction of movement of people who are well, but presumed to have been exposed to a communicable disease, is an ancient tool of public health that is still used today to mitigate the spread of infectious diseases. Instructions for quarantine can be found in the Old Testament regarding leprosyi, and it has been used throughout time as one of the few tools to reduce the spread of disease in the absence of treatments or cures. In the United States, quarantine regulations date back to 1647, when ships had to be inspected upon arrival in Boston harbor.ii This was followed by a series of state laws passed to institute quarantines in response to the infectious disease scourges of the time, including Yellow Fever, plague and smallpox.iii,iv During the same period, the federal government passed multiple statutes, which were eventually consolidated into the 1944 Federal Public Health Service Act, governing foreign and interstate quarantine.v Quarantine within a state remained a power reserved to the states under the 10th Amendment of the Constitution.

The 2014–2016 Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) outbreak renewed discussion in the United States (U.S.) around quarantine, as decision makers rushed to restrict the movements of individuals returning from the epicenter of the outbreak in West Africa. Jurisdictions and institutions around the country instituted vastly different rules, resulting in several high-profile cases that questioned not only the utility of quarantine, but the legality of the tool.vi,vii,viii Even though there were only a handful of cases in the U.S., the spread of Ebola from West Africa resulted in widespread panic amongst concerned citizens and highlighted serious gaps within the U.S. federal and state level protocols for handling highly infectious diseases, educating the public on the use of scientific evidence, and protecting civil liberties.

In our previous work, we conducted a comparative study of how quarantine has been used around the world and found that, based on our expert opinion, in order for quarantine to be successful – with success defined as the willingness of the population to participate as well as mitigation of disease risks – several conditions needed to be met: 1. The population needs to acknowledge that the disease is a threat to their safety or the safety of their community; 2. The population must trust that the government response will, in fact, mitigate the consequences of the disease; and 3. The population needs to be willing to sacrifice individual civil liberties for the betterment of the group. The trust in government is derived, in part, from the use of proven quarantine methodologies that still empower a population used to expressing strong civil liberties.ix

We followed this comparative study by an examination of how Tuberculosis (TB) is controlled across the U.S., and interviewed TB control officers from state and local public health departments to better understand the resources they use to isolate persons infected with active TB disease (as opposed to quarantining persons who are well but have been exposed), what incentives they had available, the effectiveness of those incentives, and what type of enabling factors helped individuals stay isolated for long periods of time. Through this work, we concluded that successful isolation must involve a process that inspires trust in government, only punishes noncompliance, and promotes a culture of social responsibility instead of punishment. Accomplishing successful isolation requires incentives and enabling factors, payments, job security, and a tiered enforcement plan.x Given the similarities between isolation and quarantine, we believe our conclusions in this study apply to quarantine as well.

Following the Ebola outbreak, the federal government revisited a previously discarded effort from a decade earlier to update the federal quarantine rules. The new rules, which went into effect in March 2017, attempt to update national level policies for instituting quarantines.xi But since most infectious disease events do not fall under federal jurisdiction, which only applies to events that cross international or state borders, we believe it is essential to review the state level laws and regulations pertaining to quarantine. This paper examines the variation in state level quarantine laws and assesses the effectiveness of these laws and regulations based on the criteria we developed in previous work.

METHODS

We first reviewed an existing database of state quarantine and isolation statues collated by the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL), which included laws from all 50 states and Washington D.C.xii In 2016 and again in 2017, we conducted a secondary review of the text of these laws utilizing West Law, Justia Law, and state websites to identify and verify when each state law was enacted and to insert updates that had occurred since the NCSL database was published in 2014. As part of this process we recorded amendment histories for each law. Key word searches included variations of “quarantine AND health” or “isolation AND health” to limit sections of state laws to health and public health codes and to separate Agriculture and Veterinary specific health codes.

All state statutes were assessed to identify which agencies or parties held authority to declare quarantine, which agencies or parties were involved in the execution and implementation, and if and how individual rights were protected. We then coded the laws according to a rubric that emerged from our previous research for effective quarantines: protection of civil liberties; enabling factors; incentives and other variables that allow for compensation; burial or cremation procedures in the event of death; and conditions that allow for least restrictive movement, as opposed to states that arrest or restrain persons as a first measure. The research team identified the categories for coding and the specific characteristics from the text that would be relevant to the category. Coding was conducted by at least one researcher, and then reviewed and validated by at least one additional researcher. Discrepancies, while very few, were resolved through team meetings where in-depth discussions led to consensus. We performed descriptive statistical analysis to identify patterns of commonality.

RESULTS

The review of quarantine and isolation laws for all 50 states and Washington D.C. revealed that many of the current laws have not been changed in decades, and those that have been updated were done so in the 1990’s and early 2000’s. The vast majority of the laws are focused on preventing the spread of specific diseases, namely TB, HIV/AIDS, and other sexually transmitted diseases and infections. Very few states mention specific modes of disease transmission, and only a few address hemorrhagic diseases or emerging infectious diseases such as SARS.

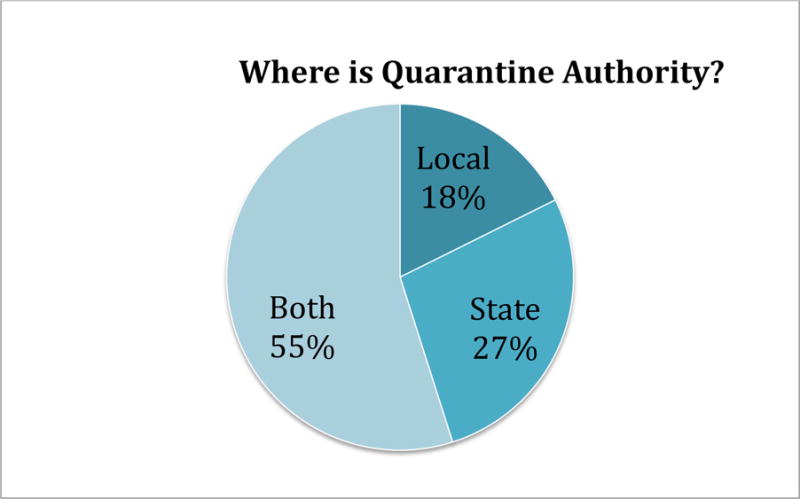

Only 10 states have updated their quarantine and isolation laws since the 2014 Ebola outbreak. However, most of these changes were minor, with the most frequent change being the inclusion the word “isolation” in order to distinguish the difference between isolation and quarantine. The second most common update was to clarify where quarantine power was vested in the state – most often at both the state and local levels. (see Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Location of Quarantine Authority

Table 1 shows which states have addressed individual rights in their quarantine laws and regulations. The majority of states allow for an individual to have a hearing (63%) and to have a voice in burial and cremation procedures of family members (71%). Few states allow for individual choice in medical provider and treatment (27%), very few provide compensation for destroyed property (16%), items (18%) or animals (4%) suspected of being infected, and only 4% have provisions for language and interpretation services.

Table 1.

State Quarantine Laws and Regulations and Individual Rights

| Civil Liberties | Medical Treatment | Compensation | Burial and Cremation | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State Orders and Directives | Right to Hearing | Right to Counsel | Indigent Services | Language and Interpretation Services | PHI | Right to Choose own Provider | Health Insurance (federal, state, or private) | Destroyed or Damaged Property | Destroyed or Damaged Items and articles | Destroyed Animals | Rights or procedures |

| AK, AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, DE, DC, FL, GA, HI, ID, IL, IN, IA, KS, KY, LA, ME, MD, MA, MN, MO, NE, NV, NH, NH, NM, NY, NC, ND, OH, OK, OR, PA, RI, SC, TN, TX, UT, VT, VA, WA, WV, WI, WY | AK, AZ, AK, CA, CT, DE, DC, GA, HI, IL, IN, KS, KY, LA, ME, MD, MA, MN, NH, NJ, NM, NC, ND, OR, RI, SC, TN, VA, WA, WV, WI, WY | AZ, AR, CT, DE, GA, HI, IL, IN, KS, KY, MN, NJ, NM, NC, ND, OR, PA, SC, UT, VA, WI | CO, CT, DE, IL, IN, LA, MD, MN, NM, NC, ND, PA, SC, TX, WI | AK, MN | AZ, DE, IL, KS, LA, ME, NV, ND, SC, VA, WY | AK, AZ, IL, IA, KY, MN, NV, NH, NM, RI, SD, TN, WI, WY | DC, HI, OR, TX, UT, WI | CA, DE, IL, MA, NM, OH, TX, VA | AZ, DE, IL, MA, NH, NJ, OH, RI, TX | IL, TX | AK, CA, CO, CT, DE, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, KS, KY, LA, ME, MD, MA, MN, MI, MO, NE, NV, NJ, NM, NY, NC, ND, OH, OR, PA, SC, TN, TX, UT, WV, WI, WY |

| 47 | 32 | 23 | 15 | 2 | 12 | 14 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 2 | 36 |

| 92% | 63% | 45.1% | 29% | 4% | 24% | 27% | 12% | 16% | 18% | 4% | 71% |

We found that 51% of states had provisions to use police powers- the ability to limit individual rights when needed to preserve the common good- to enforce public health actions.xiii Only 20% of states had provisions to protect employment when an individual is under quarantine. 45% of states had language that called for plans and budget for safe and humane quarantines and 49% had language that called for plans and budgets in place to support quarantines outside of individual homes. (See Table 2)

Table 2.

State Quarantine Laws and Regulations: Police Powers, Employment Protection and Enabling Factors

| Legal and regulatory environment | Enabling Factors

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Police Powers to Assist PH Enforcement | Employ-ment Protection | Minimal payment to individuals not receiving wages | Policy and Budget for food and water | Plan and budget for safe and humane Q | Plan, budget for external lodging (not home) | Plan, budget for communication devices | |

| Total | 26 | 10 | 5 | 12 | 23 | 25 | 7 |

| % | 51% | 20% | 10% | 24% | 45% | 49% | 14% |

Of interest, many state laws included unexpected subsections. For example, one of Hawaii’s laws states that quarantined individuals must be responsible for their own food, lodging, and medical care if their insurance does not cover medical quarantine. Hawaii also prohibits multiple individuals drinking from the same cup. In Indiana, quarantined individuals are allowed to keep their firearms unless they are quarantined in a mass quarantine location. Minnesota allows family members to enter a quarantine or isolation area at their own risk, and says that these individuals cannot hold the state, Commissioner of Health, or the Department of Health responsible for what happens to them. Alabama has a law that allows quarantine officers to ride trains and boats for free, and Rhode Island still includes language regarding flying the yellow quarantine flag on ships. These examples are indicative not just of the age of some of the language, but of just how much variation there is from state to state.

DISCUSSION

While most states have language to protect civil liberties, it is far from comprehensive. Fewer than half of state laws even include right to counsel during a quarantine, and many fewer have written protections for being able to choose a medical provider or receive compensation for damages that may occur. While half of states have granted explicit police powers to enforce public health actions during a quarantine, half do not. And only 20% provide any employment protection for individuals forced to stay away from work for the betterment of society. More worrisome, less that half of states have language in their laws and regulations related to providing safe and humane quarantines.

We highlight some of the oddities we found in state laws and regulations, but aside from being entertaining, we believe the variation between states and the inclusion of curious rules creates an environment across the country that will result in unease, confusion and possibly civil unrest if large scale quarantines are ever required.

The national debate over quarantine that started during the 2014–2016 Ebola outbreak has resulted in changes in Federal regulations. But most decisions will be made at the state and local level, governed by state law. It is the state legal and regulatory frameworks for quarantine that need to be examined most. Yet when we examine them, we find them lacking.

IMPLICATIONS FOR POLICY AND PRACTICE.

The current state level quarantine laws and regulations are outdated and insufficient to support an effective quarantine in present times. Decision makers at the state and local level must make a concerted effort to revise and update quarantine laws and regulations. Ideally, these laws and regulations should be harmonized so as to avoid confusion and disruption between states, and states and localities should work with populations to identify and address the factors that will support successful quarantines if they are ever required.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

This research was supported by Grant Number 105738 from NIH/NIAID. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIAID.

Footnotes

Contributor Statement:

RK conceptualized, designed and supervised the study and drafted the manuscript. AV conducted analytical work and other research support, and contributed to the manuscript. AF and JC conducted analytical work and other research support on the project. All authors approve the manuscript.

References

- i.Bible Gateway. New International Version. Leviticus. 13:46. https://www.biblegateway.com. Numbers 5:4. [Google Scholar]

- ii.Massachusetts State Board of Health. Acts Relating to the Establishment of Quarantine of Massachusetts: From the settlement of Massachusetts Bay to present time Rockwell and Churchill City Printers. 1881 [Google Scholar]

- iii.Tyson P A Short History of Quarantine. NOVA; Oct, 2004. Available at: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/body/short-history-of-quarantine.html. [Google Scholar]

- iv.Tandy EC. Local Quarantine and Inoculation for Smallpox in the American Colonies (1620–1775) Am J Public Health (N Y) 1923 Mar;13(3):203–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.13.3.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- v.Vanderhook KL. A History of Federal Control of Communicable Diseases: Section 361 of the Public Health Service Act. 2002 Apr 30; Available at: https://dash.harvard.edu/bitstream/handle/1/8852098/vanderhook2.html?sequence=4.

- vi.ACLU and Yale Global Health Justice Partnership. Fear, Politics, and Ebola How Quarantines Hurt the Fight Against Ebola and Violate the Constitution. 2015 Dec; Available at: https://www.aclu.org/sites/default/files/field_document/aclu-ebolareport.pdf.

- vii.Kraemer JD, Siedner MJ, Stoto MA. Analyzing Variability in Ebola-Related Controls Applied to Returned Travelers in the United States. Health Secur. 2015 Sep-Oct;13(5):295–306. doi: 10.1089/hs.2015.0016. Epub 2015 Sep 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- viii.ACLU and Yale Global Health Justice Partnership. Fear, Politics, and Ebola How Quarantines Hurt the Fight Against Ebola and Violate the Constitution. 2015 Dec; Available at: https://www.aclu.org/sites/default/files/field_document/aclu-ebolareport.pdf.

- ix.Katz R. Pandemic Preparedness Summit. College Station; Texas: Sep 18, 2015. Changing the culture of quarantine. (Scowcroft Paper No. 4). Available at: http://bush.tamu.edu/scowcroft/papers/katz/Katz%20Paper%20Final%20Publication%20Copy.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- x.Katz R, Vaught A. Approaches to Isolation of Tuberculosis Cases in the United States. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 2016 Nov; doi: 10.1017/dmp.2016.138. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2016.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- xi.Hodge J, Gostin LO, Parmet WE, Nuzzo J, Phelan A. Federal Powers to Control Communicable Conditions: Call for Reforms to Assure National Preparedness and Promote Global Security. Health Security. 2017;15(1):1–4. doi: 10.1089/hs.2016.0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xii.National Conference of State Legislators. State Quarantine and Isolation Statutes. 2014 Oct; Available at: http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/state-quarantine-and-isolation-statutes.aspx.

- xiii.Galva JE, Atchinson C, Levey S. Public health strategy and the police powers of the state. Public Health Reports. 2005;120(Suppl 1):20–27. doi: 10.1177/00333549051200S106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]