Abstract

Background

This is an update of the original Cochrane review first published in Issue 1, 2003, and previously updated in 2009 and 2012. Chronic pain affects many children, who report severe pain, disability, and distressed mood. Psychological therapies are emerging as effective interventions to treat children with chronic or recurrent pain. This update focuses specifically on psychological therapies delivered face‐to‐face, adds new randomised controlled trials (RCTs), and additional data from previously included trials.

Objectives

There were three objectives to this review. First, to determine the effectiveness on clinical outcomes of pain severity, disability, depression, and anxiety of psychological therapy delivered face‐to‐face for chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents compared with active treatment, waiting‐list, or standard medical care. Second, to evaluate the impact of psychological therapies on depression and anxiety, which were previously combined as 'mood'. Third, we assessed the risk of bias of the included studies and the quality of outcomes using the GRADE criteria.

Search methods

Searches were undertaken of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE, and PsycINFO. We searched for further RCTs in the references of all identified studies, meta‐analyses, and reviews. Trial registry databases were also searched. The date of most recent search was January 2014.

Selection criteria

RCTs with at least 10 participants in each arm post‐treatment comparing psychological therapies with active treatment, standard medical care, or waiting‐list control for children or adolescents with episodic, recurrent or persistent pain were eligible for inclusion. Only trials conducted in person (face‐to‐face) were considered. Studies that delivered treatment remotely were excluded from this update.

Data collection and analysis

All included studies were analysed and the quality of outcomes were assessed. All treatments were combined into one class, psychological treatments. Pain conditions were split into headache and non‐headache. Both conditions were assessed on four outcomes: pain, disability, depression, and anxiety. Data were extracted at two time points; post‐treatment (immediately or the earliest data available following end of treatment) and at follow‐up (between three and 12 months post‐treatment).

Main results

Seven papers were identified in the updated search. Of these papers, five presented new trials and two presented follow‐up data for previously included trials. Five studies that were previously included in this review were excluded as therapy was delivered remotely. The review thus included a total of 37 studies. The total number of participants completing treatments was 2111. Twenty studies addressed treatments for headache (including migraine); nine for abdominal pain; two for mixed pain conditions including headache pain, two for fibromyalgia, two for recurrent abdominal pain or irritable bowel syndrome, and two for pain associated with sickle cell disease.

Analyses revealed psychological therapies to be beneficial for children with chronic pain on seven outcomes. For headache pain, psychological therapies reduced pain post‐treatment and at follow‐up respectively (risk ratio (RR) 2.47, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.97 to 3.09, z = 7.87, p < 0.01, number needed to treat to benefit (NNTB) = 2.94; RR 2.89, 95% CI 1.03 to 8.07, z = 2.02, p < 0.05, NNTB = 3.67). Psychological therapies also had a small beneficial effect at reducing disability in headache conditions post‐treatment and at follow‐up respectively (standardised mean difference (SMD) ‐0.49, 95% CI ‐0.74 to ‐0.24, z = 3.90, p < 0.01; SMD ‐0.46, 95% CI ‐0.78 to ‐0.13, z = 2.72, p < 0.01). No beneficial effect was found on depression post‐treatment (SMD ‐0.18, 95% CI ‐0.49 to 0.14, z = 1.11, p > 0.05). At follow‐up, only one study was eligible, therefore no analysis was possible and no conclusions can be drawn. Analyses revealed a small beneficial effect for anxiety post‐treatment (SMD ‐0.33, 95% CI ‐0.61 to ‐0.04, z = 2.25, p < 0.05). However, this was not maintained at follow‐up (SMD ‐0.28, 95% CI ‐1.00 to 0.45; z = 0.75, p > 0.05).

Analyses revealed two beneficial effects of psychological treatment for children with non‐headache pain. Pain was found to improve post‐treatment (SMD ‐0.57, 95% CI ‐0.86 to ‐0.27, z = 3.74, p < 0.01), but not at follow‐up (SMD ‐0.11, 95% CI ‐0.41 to 0.19, z = 0.73, p > 0.05). Psychological therapies also had a beneficial effect for disability post‐treatment (SMD ‐0.45, 95% CI ‐0.71 to ‐0.19, z = 3.40, p < 0.01), but this was not maintained at follow‐up (SMD ‐0.35, 95% CI ‐0.71 to 0.02, z = 1.87, p > 0.05). No effect was found for depression or anxiety post‐treatment (SMD ‐0.07, 95% CI ‐0.30 to 0.17, z = 0.54, p > 0.05; SMD ‐0.15, 95% CI ‐0.36 to 0.07, z = 1.33, p > 0.05) or at follow‐up (SMD 0.06, 95% CI ‐0.16 to 0.28, z = 0.53, p > 0.05; SMD 0.05, 95% CI ‐0.24 to 0.33, z = 0.32, p > 0.05).

Authors' conclusions

Psychological treatments delivered face‐to‐face are effective in reducing pain intensity and disability for children and adolescents (<18 years) with headache, and therapeutic gains appear to be maintained, although this should be treated with caution for the disability outcome as only two studies could be included in the follow‐up analysis. Psychological therapies are also beneficial at reducing anxiety post‐treatment for headache. For non‐headache conditions, psychological treatments were found to be beneficial for pain and disability post‐treatment but these effects were not maintained at follow‐up. There is limited evidence available to estimate the effects of psychological therapies on depression and anxiety for children and adolescents with headache and non‐headache pain. The conclusions of this update replicate and add to those of the previous review which found that psychological therapies were effective in reducing pain intensity for children with headache and non‐headache pain conditions, and these effects were maintained at follow‐up for children with headache conditions.

Keywords: Adolescent, Child, Humans, Abdominal Pain, Abdominal Pain/therapy, Chronic Pain, Chronic Pain/etiology, Chronic Pain/psychology, Chronic Pain/therapy, Cognitive Therapy, Fibromyalgia, Fibromyalgia/therapy, Headache, Headache/therapy, Hemoglobin SC Disease, Hemoglobin SC Disease/complications, Mood Disorders, Mood Disorders/therapy, Pain Management, Pain Management/methods, Pain Management/psychology, Psychotherapy, Psychotherapy/methods, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Recurrence

Psychological therapies for the management of chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents

Psychological therapies (e.g. relaxation, hypnosis, coping skills training, biofeedback, and cognitive behavioural therapy) may help people manage pain and its disabling consequences. Therapies can be delivered face‐to‐face by a therapist, via the Internet, by telephone call, or by computer programme. This review focuses on treatments that are delivered face‐to‐face by a therapist. For children and adolescents there is evidence that both relaxation and cognitive behavioural therapy (treatment that helps people test and revise their thoughts and actions) are effective in reducing the intensity of pain in chronic headache, recurrent abdominal pain, fibromyalgia, and sickle cell disease immediately after treatment.

Psychological therapies also have a lasting effect in reducing pain and disability for chronic headache. Fifty‐six per cent of children who were treated with psychological therapies reported less pain compared with 22% of children who did not receive a psychological therapy. Anxiety was also reduced for children with headaches immediately following treatment. Psychological therapies also reduce pain and disability for children with mixed pain conditions (excluding headache) immediately following treatment. However, we did not find that any treatment effects were maintained at follow‐up (between 3‐12 months after the end of treatment) for children with mixed pain conditions. Psychological therapies did not produce changes in depression in children with either headache or non‐headache conditions, and anxiety did not change in children with non‐headache conditions receiving psychological therapies.

More studies are needed to understand whether psychological therapies can improve depression and anxiety and have more lasting effects on pain and disability in other groups of young people who have chronic pain.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison.

| Psychological therapies compared with any control for children with frequent headache | ||||||

|

Patient or population: children and adolescents with frequent headache Settings: Community Intervention: Psychological therapies Comparison: Any control | ||||||

| Outcome | Probable outcome with control | Probable outcome with intervention | NNT and/or relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Pain (low scores mean lower pain ratings) | 220 in 1000 | 560 in 1000 |

NNT = 2.94 RR 2.47 (1.97 to 3.09) |

714 participants, 302 events (15 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | Majority of studies included in analysis had high risk of bias, and mostly wait‐list controls. |

| Pain (at follow‐up) (low scores mean lower pain ratings) | 478 in 1000 | 750 in 1000 |

NNT = 3.67 RR 2.89 (1.03 to 8.07) |

251 participants, 158 events (5 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low | Majority of studies included in analysis had high risk of bias, wide confidence intervals, heterogeneity >45%, low number of participants, and some studies did not report full outcomes in published paper. |

| Disability (low scores mean lower disability ratings) | The mean disability in the intervention groups was 0.49 standard deviations lower (0.74 to 0.24 lower) | 263 participants (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | A low number of participants could be included in the analysis and some studies did not report full outcomes in published paper. SMD ‐0.49 (‐0.74 to ‐0.24) |

||

| Disability (at follow‐up) (low scores mean lower disability ratings) | The mean disability (at follow‐up) in the intervention groups was 0.46 standard deviations lower (0.78 to 0.13 lower) | 148 participants (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | A low number of participants could be included in the analysis. SMD ‐0.46 (‐0.78 to ‐0.13) |

||

| Depression (low scores mean lower depression ratings) | The mean depression in the intervention groups was 0.18 standard deviations lower (0.49 lower to 0.14 higher) | 164 participants (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate | A low number of participants could be included in the analysis. SMD ‐0.18 (‐0.49 to 0.14) |

||

| Anxiety (low scores mean lower anxiety ratings) | The mean anxiety in the intervention groups was 0.33 standard deviations lower (0.61 to 0.04 lower) | 203 participants (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | A low number of participants could be included in the analysis and some studies did not report full outcomes in published paper. SMD ‐0.33 (‐0.61 to ‐0.04) |

||

| Anxiety (at follow‐up) (low scores mean lower anxiety ratings) | The mean anxiety (at follow‐up) in the intervention groups was 0.28 standard deviations lower (1 lower to 0.45 higher) | 67 participants (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low | The analysis included wide confidence intervals, heterogeneity >45%, low number of participants, and some studies did not report full outcomes in published paper. SMD ‐0.28 (‐1.00 to 0.45) |

||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

NNT: number needed to treat for an additional beneficial effect; RR: risk ratio; CI: Confidence interval; SMD: Standardised Mean Difference.

Summary of findings 2.

| Psychological therapies compared with any control for children with non‐headache pain | ||||||

|

Patient or population: children and adolescents with non‐headache pain Settings: Community Intervention: Psychological therapies Comparison: Any control | ||||||

| Outcome | Probable outcome with control | Probable outcome with intervention | NNT and/or relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Pain (low scores mean lower pain ratings) | The mean pain in the intervention groups was 0.57 standard deviations lower (0.86 to 0.27 lower) | 852 participants (13 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low | Majority of studies had high risk of bias, heterogeneity >45%, some studies did not fully report outcomes in published paper. SMD ‐0.57 (‐0.86 to ‐0.27) |

||

| Pain (at follow‐up) (low scores mean lower pain ratings) | The mean pain (at follow‐up) in the intervention groups was 0.11 standard deviations lower (0.41 lower to 0.19 higher) | 543 participants (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | Heterogeneity >45% and some studies did not fully report outcomes in published paper. SMD ‐0.11 (‐0.41 to 0.19) |

||

| Disability (low scores mean lower disability ratings) | The mean disability in the intervention groups was 0.45 standard deviations lower (‐0.71 to ‐0.19) | 764 participants (11 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low | Majority of studies had high risk of bias, heterogeneity >45%, some studies did not fully report outcomes in published paper. SMD ‐0.45 (‐0.71 to ‐0.19) |

||

| Disability (at follow‐up) (low scores mean lower disability ratings) | The mean disability in the intervention groups was 0.35 standard deviations lower (0.71 lower to 0.02 higher) | 508 participants (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | Heterogeneity >45% and some studies did not fully report outcomes in published paper. SMD ‐0.17 (‐0.71 to 0.02) |

||

| Depression (low scores mean lower depression ratings) | The mean depression in the intervention groups was 0.07 standard deviations lower (0.3 lower to 0.17 higher) | 538 participants (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate | Some studies did not fully report outcomes in published paper. SMD ‐0.07 (‐0.3 to 0.17) |

||

| Depression (at follow‐up) (low scores mean lower depression ratings) | The mean anxiety in the intervention groups was 0.06 standard deviations higher (0.16 lower to 0.28 higher) | 473 participants (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate | Some studies did not fully report outcomes in published paper. SMD 0.06 (‐0.16 to 0.28) |

||

| Anxiety (low scores mean lower anxiety ratings) | The mean anxiety in the intervention groups was 0.15 standard deviations lower (0.36 lower to 0.07 higher) | 498 participants (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate | Some studies did not fully report outcomes in published paper. SMD 0.15 (‐0.36 to 0.07) |

||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

CI: Confidence interval; SMD: Standardised Mean Difference.

Background

Description of the condition

This review is an update of a previously published review in the The Cochrane Library on 'Psychological therapies for the management of chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents' (Eccleston 2012). Chronic and recurrent pain (pain lasting more than three months) is a common problem in young people. Recent epidemiology gives a prevalence of 15% to 30%, with 8% of children described as having severe and frequent pain (Perquin 2000; Perquin 2001; Stanford 2008). The most common location for pain is in the head, abdomen, and limbs (Perquin 2000). All types of chronic and recurrent pain are more commonly reported by girls, and there is a peak in incidence at ages 14 to 15 years (Stanford 2008). Young people report pain to be distressing and interfering, and in some cases this can be severely debilitating, affecting all aspects of a child's life (Bursch 1998; Palermo 2000), and the lives of their parents and family members (Palermo 2005; Walker 1989). The deleterious effects of untreated pain in childhood can also extend to adulthood (Fearon 2001).

Description of the intervention

There is a broad family of treatments included in the general term 'psychological'. In essence, treatments are specifically designed to alter psychological processes thought to underlie or significantly contribute to pain, distress, and/or disability. The design of psychological treatments is normally informed by specific theories of the aetiology of human behaviour, or treatments have developed pragmatically through observation and study of response to intervention. Behavioural and cognitive treatments designed to ameliorate pain, distress, and disability were first introduced in adults over 40 years ago and have become well established (Fordyce 1968; Keefe 2004). A companion review of psychological treatments for the management of chronic pain in adults is also published (Williams 2012). Treatments were originally developed to be delivered in a face‐to‐face delivery format in which the patients and therapists work together in person to implement therapeutic strategies. Methods of remote delivery of psychological treatments have been developed. These are the subject of a separate Cochrane review ('Psychological therapies (remotely delivered) for the management of chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents' (protocol in press)).

How the intervention might work

In paediatric practice, the treatments have a shorter history and different therapeutic aims and components than those for adults. In general, psychological treatments aim to control pain and modify situational, emotional, familial, and behavioural factors that play a role in pain or related consequences (e.g. McGrath 1990). A variety of intervention strategies have been designed to reduce pain experience, increase comfort, and/or reduce associated disability and dysfunction in children with pain conditions. Behavioural strategies include relaxation training, biofeedback, and behavioural management programmes (e.g. teaching parents operant strategies to reinforce adaptive behaviours such as school attendance). Cognitive strategies include hypnosis, stress management, guided imagery, and cognitive coping skills (Palermo 2012).

Cognitive behavioural programmes incorporate elements of both behavioural and cognitive strategies. Given that headache and abdominal pain are the most common types of recurrent pain in children, most of the treatment literature has focused on these two populations. By far the most commonly described treatment is relaxation training and/or biofeedback for headache, and recommendations have been made to offer psychological treatment as a matter of routine care for children with headaches (Masek 1999). In an effort to enhance the efficiency of psychological treatments for children with headache, more recent treatment developments have compared different elements of relaxation training and biofeedback with a variation in treatment formats (individual and group), treatment dose, and treatment setting (clinic, school, and home).

Psychological therapies have also been developed to treat children with non‐headache chronic and recurrent pain including children with abdominal, musculoskeletal, and disease‐related pain. Multidisciplinary pain treatment programmes for children have recently become a standard of care (McGrath 1999a), and now many specialised pain clinics are available for children with chronic or recurrent pain, which may involve outpatient care or intensive inpatient rehabilitation. Such programmes offer physical rehabilitation, psychological treatment, and medical strategies, and aim to restore function rather than provide pain relief. Case series and uncontrolled studies provide evidence for the effectiveness of multidisciplinary treatment with psychological therapy for paediatric chronic and recurrent pain (Eccleston 2003b).

Why it is important to do this review

Several reviews have documented the effectiveness of psychological therapies for children with headache, abdominal, and disease‐related pain (Holden 1999; Huertas‐Ceballos 2008; Janicke 1999; Kibby 1998; Walco 1999; Weydert 2003). Four reviews have used data pooling techniques for studies of children with headache (Eccleston 2012; Fisher 2014; Hermann 1995; Trautmann 2006). In their review of paediatric migraine, Hermann 1995 found that biofeedback and muscle relaxation are more effective than placebo treatments and prophylactic drug treatments in controlling headache. In the previously published Cochrane review (Eccleston 2012), we found that psychological treatments were effective in reducing pain intensity in youths with headache and non‐headache pain. Fisher 2014 reported similar findings for children and adolescents with headache. Trautmann 2006 conducted a meta‐analysis of psychological treatment for recurrent headache in children, finding small effect sizes across three headache variables: frequency, duration, and intensity, although reduction in pain intensity at post‐treatment was a statistically significant effect. A large binomial effect size of 50% or greater reduction in headache symptoms was reported.

Developments in paediatric psychology have led to new populations of children being treated. The aim of this review is to update the published evidence on the efficacy of psychological treatments for chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents. In this review, we aim to focus specifically on therapy delivered in person (face‐to‐face) rather than remotely to the child in order to estimate treatment effects among studies using a relatively homogenous delivery method. A separate review for The Cochrane Library focused on remotely delivered treatments for youth with chronic pain is currently in progress ('Psychological therapies (remotely delivered) for the management of chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents' (protocol in press)). In this review, we also aim to examine the impact of psychological therapies on 'mood' in more detail than previous reviews by separating depression and anxiety into discrete outcome domains.

Objectives

The primary objective of this updated review was to determine the effectiveness on clinical outcomes of pain severity, disability, depression, and anxiety of psychological therapy delivered face‐to‐face for chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents compared with active treatment, waiting‐list, or standard medical care.

The secondary objective was to examine the impact of psychological therapies on children's mood symptoms with more specificity by evaluating depression and anxiety as discrete outcomes.

The third objective was to describe the risk of bias of included studies and the quality of outcomes using the GRADE criteria.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing a credible psychological treatment, or a compound treatment with credible primary psychological content, to an active treatment, treatment as usual, or waiting‐list control. Content was judged credible if it was based on an extant psychological theory or framework.Studies were excluded if the pain was associated with cancer or other medical conditions (e.g. diabetes) or the therapy was delivered remotely using methods such as telephone or Internet.

Studies were included if they:

were available as a full report of a RCT;

had a design that placed a psychological treatment as an active treatment of primary interest;

had a psychological treatment with definable psychotherapeutic content (although not necessarily delivered by someone with psychological qualifications);

were published (or electronically pre‐published) in a peer‐reviewed scientific journal;

participants reported chronic (i.e. at least three months duration) or recurrent (episodic) pain;

had 10 or more participants in each treatment arm at the end‐of‐treatment assessment; and

included a psychological intervention that was delivered in person (face‐to‐face treatment).

Types of participants

Children and adolescents (<18 years) reporting persistent, recurrent, or episodic pain in any body site, not associated with cancer or other medical conditions (e.g. diabetes).

Types of interventions

Studies were included if at least one trial arm consisted of a psychological intervention delivered face‐to‐face, and a comparator arm consisted of active treatment, treatment as usual, or waiting‐list control. Primary interventions that were delivered remotely via other methods (e.g., Internet, telephone) were excluded.

Types of outcome measures

Data were collected on descriptive characteristics of patients and characteristics of the treatments, including treatment setting and treatment dose (duration).

All measurement instruments reported in each study were assessed and recorded. The most appropriate measurement instruments for the four domains of pain, disability, depression, and anxiety were selected.

Any mention of adverse events was also recorded.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

RCTs of any psychological therapy for paediatric chronic or recurrent pain were identified by searching CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE, and PsycINFO from their inception to January 2014. Four separate searches have been undertaken. The first search was undertaken from inception of the abstracting services to the end of 1999 (Eccleston 2003a), the second searched databases from 1999 to 2008 (Eccleston 2009), the third searched databases from 2008 to March 2012 (Eccleston 2012), and the fourth from 2012 to 21st January 2014.

Further, trial registries were searched for possible ongoing or complete trials in this area. Reference lists of included studies and relevant systematic reviews were examined for other potential RCTs.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The selection of included studies was made using the following criteria; the study had to be RCT in design and published in a peer‐reviewed journal, include children (<18 years of age) who have chronic pain (non‐cancer pain), include a psychological intervention as an active treatment, and have > 10 participants in each arm at each extraction time‐point. Studies that have not been peer reviewed were excluded in order to keep the quality of included studies high. For this update, psychological therapies delivered remotely (e.g., Internet, telephone) were excluded. Psychological interventions were considered for inclusion if they had credible, recognisable psychological/psychotherapeutic content and were specifically designed to change the child's behaviour, cognition, and/or mood. The trials used in the previous systematic review and meta‐analysis were considered automatically eligible for inclusion (Eccleston 2012).

Data extraction and management

Data extracted included: details relating to the design of the study, the participants, primary diagnosis, method of treatment, adverse events, outcome measurement tools used, and outcome data for computation of effect sizes. When data were missing for primary outcomes of interest, we contacted trial authors via email to obtain data necessary for effect size calculations. Data suitable for pooling were entered into RevMan 5.2 (RevMan 2012).

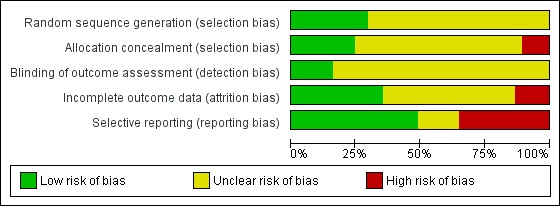

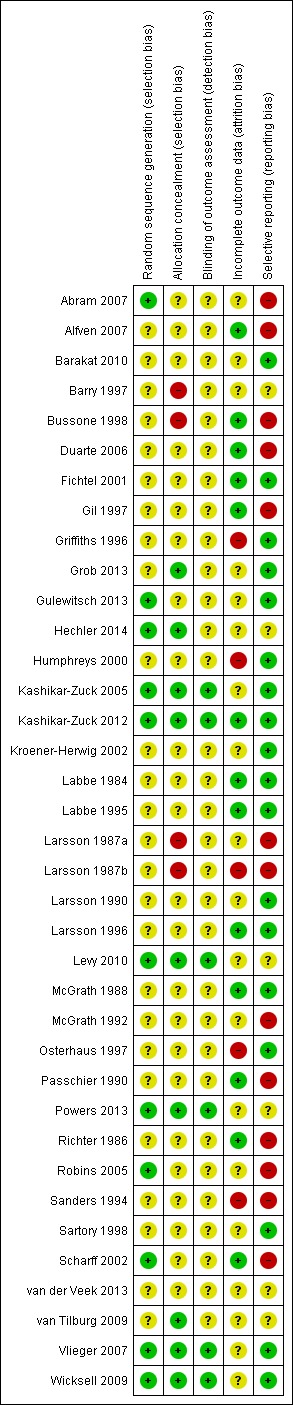

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias was measured using the recommended Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2011). We assessed five categories from this tool; random sequence generation (selection bias), allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), and selective reporting (reporting bias). 'Blinding of participant or personnel' (performance bias) was excluded for the purposes of this review as we deemed it redundant because of the nature of delivering or receiving a psychological intervention.

Judgements were made on the categories using the following rules. Random sequence generation judgements were based on whether authors gave a convincing method of randomisation. Allocation concealment bias judgements were based on whether there were convincing methods used for random allocation to take place. Participants being stratified by age or gender were not deemed as biased. Blinding of outcome assessment was judged on whether the measures were taken by a third party who was blind to the treatment condition. Incomplete outcome data bias judgements were based on whether attrition was fully reported. Authors had to report attrition at each measurement time point (post‐treatment and follow‐up), and state whether there were any significant differences between completers and non‐completers. Finally, selective reporting bias was judged on whether data could be fully extracted for analyses in this review. If authors provided data when requested, we would have marked this category as 'unclear bias'.

Summary of findings tables using the GRADE criteria are presented separately for outcomes for children with headache and non‐headache pain conditions (Table 1, Table 2). The GRADE table presents 'probable outcomes' for the control and intervention group, rather than 'assumed risk' and 'corresponding risk' as presented in traditional GRADE tables. The probable outcome of events was calculated per 1000 for both the control group and those receiving psychological therapies, similar to other reviews including patients with pain conditions (e.g. Moore 2014). The studies included for each outcome were judged using five criteria: risk of bias, indirectness, inconsistency, imprecision, and publication bias. Limitations in the design and implementation were used to assess the overall risk of bias of included studies for each outcome. An outcome was downgraded if the majority of studies had unclear or high risk of bias. Indirectness was assessed if a population, intervention, or outcome was not of direct interest to the review (e.g. using mostly wait‐list controls). Inconsistency was determined by the heterogeneity of results. If an outcome had a heterogeneity outcome of >45%, the outcome quality was downgraded. Imprecision was assessed by the number of participants included in an outcome and confidence intervals. Outcomes were downgraded when only a small number of participants could be included in the analysis, or the analysis had wide confidence intervals. Finally, publication bias was downgraded if studies failed to report outcomes in the published manuscript or if there was a suspicion that null findings had not been published or reported (Higgins 2011).

Each outcome was given a quality marking ranging from 'very low' to 'high'. High quality ratings are given when "further research is unlikely to change our estimate of effect". Moderate ratings are given when "further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate". Low quality is given when "further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate". Finally, very low quality is given when "we are very uncertain about the estimate" (p. 404, Balshem 2011). The seven 'most important outcomes' were reported in each table (Guyatt 2013). Therefore, the seven outcomes that reported the largest amount of participants were included in each summary of findings table.

Measures of treatment effect

All treatments labelled as psychological were combined in the following meta‐analyses, and designated "Treatment". Similarly, all control conditions were combined and designated "Control". Where more than one intervention or control group was reported the intervention or control arms were combined to create a single pairwise comparison in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). The studies were divided into two groups based on pain condition. The first group was labelled "headache" and the second group "non‐headache". Two assessment points were also selected: post‐treatment and follow‐up. Post‐treatment is the assessment point occurring soonest following treatment (often after a delay of several weeks to allow for recording of episodic pain), and follow‐up is the assessment point at least three months after the post‐treatment assessment point, but not more than 12 months, and the longer time point was selected if there were two follow‐up assessments within this time frame. Therefore, four separate comparisons were designed comprising two forms of comparator (Treatment, Control) and two assessment time points (post‐treatment and follow‐up). They were labelled as follows.

Treatment versus control (headache) post‐treatment.

Treatment versus control (headache) follow‐up.

Treatment versus control (non‐headache) post‐treatment.

Treatment versus control (non‐headache) follow‐up.

Multiple measurement tools were typically used in each study. For each comparison, four outcomes were identified and labelled 'Pain', 'Disability', 'Depression', and 'Anxiety'. From each trial we selected the measure considered most appropriate for each outcome. To guide the choice of outcome measure, we applied two rules. First, if an outcome measure was established and occurred frequently among studies it was selected over more novel instruments. Second, given a choice between single item and multi‐item self‐report tools, multi‐item tools were chosen on the basis of inferred increased reliability. Studies did not necessarily report data in all four outcomes. For headache treatments, the data for pain outcomes were dichotomous so relative ratios or risk ratios (RR) were used, and we calculated numbers needed to treat to benefit (NNTBs). For disability, depression, and anxiety outcomes, continuous data were used. Continuous data were used for pain, disability, depression, and anxiety for non‐headache studies. Effect sizes can be interpreted as follows; small = 0.2, medium = 0.5, large = 0.8 (Cohen 1992).

Data synthesis

For dichotomous outcomes, such as achieved (or failed to achieve) 50% reduction in pain, we calculated the RR using 95% confidence intervals (CI) and a random‐effects model. For ease of interpretation, the risk ratio (RR) and NNTB are reported. For continuous outcomes (such as rating scales) we calculated the standardised mean differences using a 95% CI and a random‐effects model. The heterogeneity of the findings are also reported.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

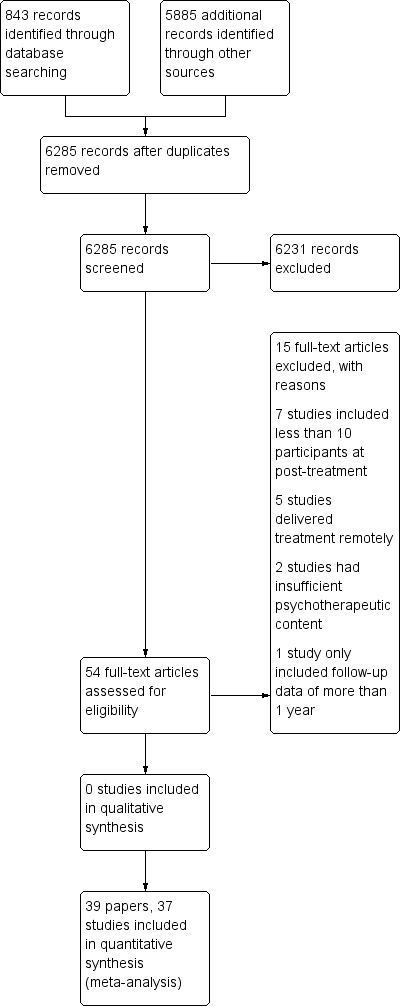

Four separate searches have been undertaken using databases from inception to January 2014 (see Figure 1). Details of the previous three searches can be found in Appendix 2. In the most recent search, databases were searched from March 2012 to January 2014. In total from the four searches, 6285 abstracts were screened. The current search yielded 443 abstracts and seven papers were included (Grob 2013; Gulewitsch 2013; Hechler 2014; Kashikar‐Zuck 2012; Levy 2010; Powers 2013; van der Veek 2013). Kashikar‐Zuck 2012 and Levy 2010 provided additional data for studies previously included in this review. Five studies that were previously included, were excluded from this review since treatment was delivered remotely (Connelly 2006; Hicks 2006; Palermo 2009; Stinson 2010; Trautmann 2010). Therefore, a total of 37 RCTs are included (39 papers) (Abram 2007; Alfven 2007; Barakat 2010; Barry 1997; Bussone 1998; Duarte 2006; Fichtel 2001; Gil 1997; Griffiths 1996; Grob 2013; Gulewitsch 2013; Hechler 2014; Humphreys 2000; Kashikar‐Zuck 2005; Kashikar‐Zuck 2012; Kroener‐Herwig 2002; Labbe 1984; Labbe 1995; Larsson 1987a; Larsson 1987b; Larsson 1990; Larsson 1996; Levy 2010; McGrath 1988; McGrath 1992; Osterhaus 1997; Passchier 1990; Powers 2013; Richter 1986; Robins 2005; Sanders 1994; Sartory 1998; Scharff 2002; van der Veek 2013; van Tilburg 2009; Vlieger 2007; Wicksell 2009).

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

The total number of participants completing treatments from the 37 studies was 2111. Of the 37 studies, one had four treatment arms, 10 had three arms, and 26 had two arms. The mean number of participants per study at the end of treatment was 57 (standard deviation (SD) 37). Girls outnumbered boys in 29 studies, and boys outnumbered girls in eight (Mean = 68% girls, range 22% to 100%). Child age was reported in 34 studies (Mean 12.45 years, SD 2.2 years). Only 16 studies reported the duration of pain, with a mean of 3.2 years.

Participants were recruited from a range of healthcare settings and other sources. Twenty‐one studies recruited from hospital or clinic settings, four from schools, six recruited volunteers from school or hospital, referrals, or recruited through advertisements, one from the community, and five did not report the source. There were 20 studies of treatments for children with headache (including migraine). Of the remainder, nine were for abdominal pain (Alfven 2007; Duarte 2006; Grob 2013; Humphreys 2000; Levy 2010; Robins 2005; Sanders 1994; van der Veek 2013; van Tilburg 2009), and two studies treated participants with either a primary diagnosis of abdominal pain or a primary diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome (Gulewitsch 2013; Vlieger 2007). Two studies treated children with fibromyalgia (Kashikar‐Zuck 2005; Kashikar‐Zuck 2012), two were for the treatment of pain associated with sickle cell disease (Barakat 2010; Gil 1997), and a further two studies included mixed pain conditions including headache and non‐headache pain (Hechler 2014; Wicksell 2009), and so data were included in both analyses as appropriate.

Treatment arms were classified on the basis of their content and of the label given by the study authors. The interventions were categorised into three broad groups. The first is best described as behavioural, typically relaxation‐based, with or without biofeedback, and including autogenic or hypnotherapeutic content (Bussone 1998; Fichtel 2001; Labbe 1984; Labbe 1995; Larsson 1987a; Larsson 1987b; Larsson 1990; Larsson 1996; McGrath 1988; McGrath 1992; Passchier 1990; Vlieger 2007). The second is best described as cognitive behavioural therapy, including cognitive coping, coping skills training, and parent behavioural strategies (Abram 2007; Alfven 2007; Barakat 2010; Barry 1997; Duarte 2006; Gil 1997; Griffiths 1996; Grob 2013; Gulewitsch 2013; Humphreys 2000; Kashikar‐Zuck 2005; Kashikar‐Zuck 2012; Kroener‐Herwig 2002; Levy 2010; McGrath 1992; Osterhaus 1997; Powers 2013; Richter 1986; Robins 2005; Sanders 1994; Sartory 1998; Scharff 2002; van der Veek 2013; van Tilburg 2009; Wicksell 2009). The third, used a three week interdisciplinary pain programme consisting of paediatricians, psychologists, psychiatrists, nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, and social workers with treatment delivered in an inpatient setting. The number of psychological content hours within this programme was 24‐31 hours (Hechler 2014). Psychological therapy delivered in this group was based on cognitive‐behavioural principles.

Different control conditions were employed and were categorised into either active control (e.g. treatment as usual, education, n = 25) or wait‐list (n = 12). Twenty‐nine studies reported extractable post‐treatment data, and 13 studies reported extractable follow‐up data of between three months and a year. Thirty‐three studies reported the treatment length; this was typically short (Mean = 6 hours 37 minutes for headache studies, Mean = 6 hours 41 minutes for non‐headache studies, Table 7). Three studies did not report the duration of psychological treatment (Alfven 2007; Humphreys 2000; Sartory 1998).

Table 1.

Duration of treatment and setting by condition

| Headache studies | |||

| Author | Illness | Treatment duration (hours) | Setting |

| Abram 2007 | Headache | 1.5 | Clinic |

| Barry 1997 | Headache | 3 | Unknown |

| Bussone 1998 | Headache | 7 | Clinic |

| Fichtel 2001 | Headache | 6.75 | Clinic |

| Griffiths 1996 | Headache | 12 | Clinic/home |

| Hechler 2014 | Mixed | 136.5 (3‐week intensive therapy) | Clinic |

| Kroener‐Herwig 2002 | Headache | 12 | Clinic |

| Labbe 1984 | Headache | 6.7 | Clinic |

| Labbe 1995 | Headache | 7.5 | Clinic |

| Larsson 1987a | Headache | 6.75 | School |

| Larsson 1987b | Headache | 5 | School |

| Larsson 1990 | Headache | 1.7 | Home |

| Larsson 1996 | Headache | 3.3 | Clinic |

| McGrath 1988 | Headache | 6 | Unknown |

| McGrath 1992 | Headache | 8 | Home/clinic |

| Osterhaus 1997 | Headache | 9.3 | Clinic |

| Passchier 1990 | Headache | 2.5 | School |

| Powers 2013 | Headache | 13 | Clinic |

| Richter 1986 | Headache | 9 | Unknown |

| Sartory 1998 | Headache | Unknown | Clinic |

| Scharff 2002 | Headache | 4 | Clinic |

| Wicksell 2009* | Mixed | 10 | Clinic |

| Non‐headache studies | |||

| Author | Illness | Treatment duration hours) | Setting |

| Alfven 2007 | RAP | Unknown | Clinic |

| Barakat 2010 | SCD | 6 | Home |

| Duarte 2006 | RAP | 3.3 | Unknown |

| Gil 1997 | SCD | 0.75 | Clinic |

| Grob 2013 | RAP | 9 | Clinic |

| Gulewitsch 2013 | RAP/IBS | 2 | Clinic |

| Hechler 2014 | Mixed | 136.5 (3‐week intensive therapy, psychological content unknown) | Clinic |

| Humphreys 2000 | RAP | Unknown | Clinic |

| Kashikar‐Zuck 2005 | Fibromyalgia | 6 | Clinic |

| Kashikar‐Zuck 2012 | Fibromyalgia | 7.5 | Unknown |

| Levy 2010 | RAP | 4 | Home/clinic |

| Robins 2005 | RAP | 3.5 | Clinic |

| Sanders 1994 | RAP | 6 | Clinic |

| van der Veek 2013 | RAP | 4.5 | Clinic |

| van Tilburg 2009 | RAP | 1.8 | Home |

| Vlieger 2007 | RAP/IBS | 5 | Clinic |

| Wicksell 2009* | Mixed | 10 | Clinic |

*Mixed headache and non‐headache studies are entered twice. Recurrent abdominal pain (RAP), sickle cell disease (SCD), juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

The setting of treatment delivery varied between studies (Table 7). Twenty‐three studies delivered treatment in a clinic, three studies delivered treatment at home (e.g. with a therapist, following a manual), and three were based either in a clinic or at home, so exposure to treatment was uncontrolled. A further three were based in schools and five were unknown. Home maintenance or practice of treatment was a common and important feature of many studies, but overall treatment exposure including home practice was not reported.

Excluded studies

Fifteen studies were excluded, of which six are new to this update (Connelly 2006; Hicks 2006; Koenig 2013; Palermo 2009; Stinson 2010; Trautmann 2010). Connelly 2006, Hicks 2006, Palermo 2009, Stinson 2010, and Trautmann 2010 were excluded as they were delivered remotely, so did not meet the new inclusion criteria. Seven studies were excluded as they had fewer than 10 participants in a treatment arm at the end of treatment (Fentress 1986; Kroener‐Herwig 1998; Larsson 1986; Sanders 1989; Trautmann 2008; Weydert 2006; Youssef 2009), two studies were judged to have insufficient psychological content in the treatment (Koenig 2013; Olness 1987), and one study reported only follow‐up data of more than one year (Vlieger 2012).

Risk of bias in included studies

All included studies were rated for risk of bias on five categories; random sequence generation (selection bias), allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), and selective reporting (reporting bias) (Figure 2; Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Figure 3.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Eleven studies were scored as low risk of bias and gave a convincing method of randomisation, a further 26 studies were judged unclear on random sequence generation as they did not provide an adequate method of randomisation. None was scored as having high risk of bias. For allocation, nine studies were judged to have a low risk of bias and gave a convincing method, 24 studies were unclear and four studies had a high risk of bias. For outcome assessment, six studies used a third person blinded to the group allocation when taking measurements, 31 studies did not report this and so were unclear. Thirteen studies reported attrition fully, reporting that there was no significant difference between completers and non‐completers. Nineteen studies only partially reported attrition and so we judged them to be unclear and five studies did not report attrition so we judged them to have a high risk of bias. Seventeen studies reported data fully, which could be extracted and used in analyses; six studies did not fully report data in the published trial, but provided data when contacted via email; 14 studies did not provide full extractable data and we judged them to have high risk of bias for selective reporting.

We attempted 16 analyses for this update (pain, disability, depression, and anxiety outcomes for headache and non‐headache conditions post‐treatment and at follow‐up). One comparison had only one eligible study and so we did not perform analysis. Of the remaining 15 comparisons, four showed low heterogeneity (I2 value below25%), four showed modest heterogeneity (I2 value over 25% to below 50%), and seven showed large heterogeneity (I2 value 50% or more).

The quality of evidence was assessed separately for headache and non‐headache outcomes using the GRADE criteria. For headache conditions, two outcomes scored very low quality meaning we were very uncertain of the estimates of pain at follow‐up, and anxiety at follow‐up. Four outcomes (pain post‐treatment, disability post‐treatment and at follow‐up, and anxiety post‐treatment) scored low quality meaning further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Depression post‐treatment scored moderate quality, meaning further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate (Summary of findings table 1). For non‐headache outcomes, the quality was higher. Two outcomes (pain and disability post‐treatment) scored very low quality. Pain and disability at follow‐up were deemed to be of low quality. All other outcomes scored moderate quality (Summary of findings table 2).

Effects of interventions

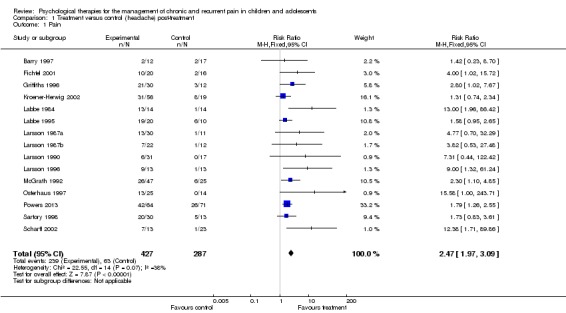

Treatment versus control (headache) post‐treatment

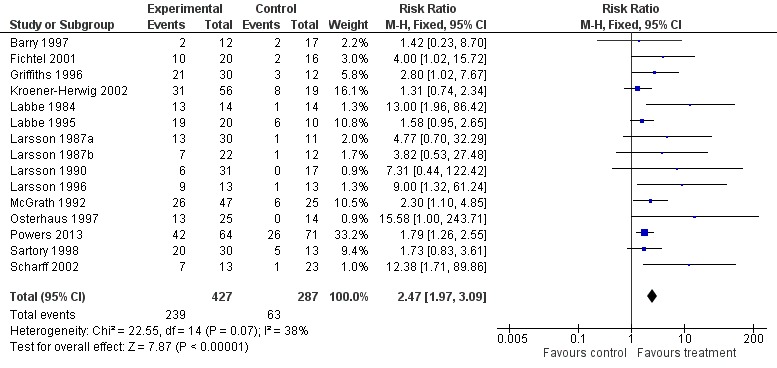

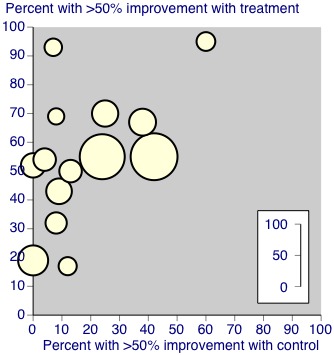

Fifteen studies with 714 participants into an analysis of the effects of treatment on pain post‐treatment (Barry 1997; Fichtel 2001; Griffiths 1996; Kroener‐Herwig 2002; Labbe 1984; Labbe 1995; Larsson 1987a; Larsson 1987b; Larsson 1990; Larsson 1996; McGrath 1992; Osterhaus 1997; Powers 2013; Sartory 1998; Scharff 2002). This analysis gave a risk ratio (RR) of 2.47 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.97 to 3.09; z = 7.87, p < 0.01) for a beneficial reduction in headache pain (number needed to treat to benefit (NNTB) = 2.94) (Analysis 1.1; Figure 4; Figure 5). However, the GRADE quality rating for this outcome was low, meaning further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate.

Analysis 1.1.

Comparison 1 Treatment versus control (headache) post‐treatment, Outcome 1 Pain.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Treatment versus control (headache) post‐treatment, outcome: 1.1 Pain.

Figure 5.

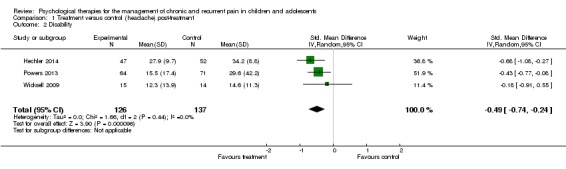

Three studies with 263 participants were included in the analysis of the effects of treatment on disability (Hechler 2014; Powers 2013; Wicksell 2009). The analysis revealed that psychological therapies were beneficial at reducing disability in children with headache, with a small effect size (Standardised mean difference (SMD) ‐0.49, 95% CI ‐0.74 to ‐0.24, z = 3.90, p < 0.01; Analysis 1.2). The quality of this outcome was scored low, meaning further research is very likely to have an important impact on the effect.

Analysis 1.2.

Comparison 1 Treatment versus control (headache) post‐treatment, Outcome 2 Disability.

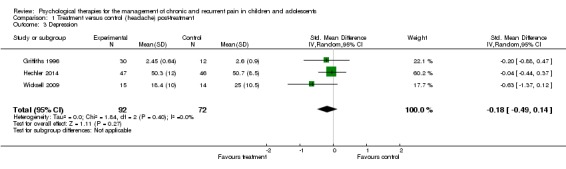

Three studies with 164 participants were entered into an analysis of the effects of treatment on depression (Griffiths 1996; Hechler 2014; Wicksell 2009). The analysis revealed that psychological therapies did not show a beneficial effect for reducing depression for children with headache (SMD ‐0.18,95% CI ‐0.49 to 0.14, z = 1.11, p > 0.05; Analysis 1.3). A moderate quality rating was judged for this outcome, meaning further research is likely to have an important impact on our estimate of effect.

Analysis 1.3.

Comparison 1 Treatment versus control (headache) post‐treatment, Outcome 3 Depression.

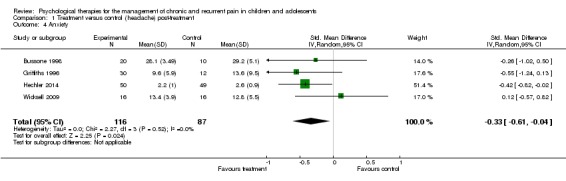

Four studies with 203 participants were entered into an analysis of the effects of treatment on anxiety at post‐treatment (Bussone 1998; Griffiths 1996; Hechler 2014; Wicksell 2009) which showed a small beneficial effect for psychological therapies (SMD ‐0.33, 95% CI ‐0.61 to ‐0.04, z = 2.25, p < 0.05; Analysis 1.4). We have low confidence in this estimate of effect.

Analysis 1.4.

Comparison 1 Treatment versus control (headache) post‐treatment, Outcome 4 Anxiety.

Out of the 20 headache studies, only Powers 2013 reported adverse events. The study authors categorised adverse events into different grades dependent on severity. There were 199 adverse events in total, although the authors do not state how many were due to the intervention. There was no difference in the severity of events between the CBT and headache education group.

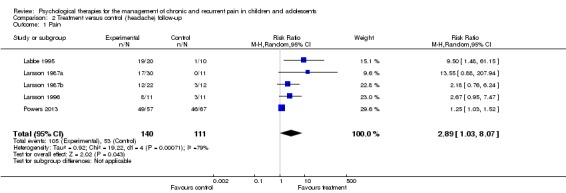

Treatment versus control (headache) follow‐up

Five studies of 251 participants were entered into analysis of the effects of treatment on pain at follow‐up (Labbe 1984; Larsson 1987a; Larsson 1987b; Larsson 1996; Powers 2013). This analysis produced a RR of 2.89 (95% CI 1.03 to 8.07; z = 2.02, p < 0.05; Analysis 2.1), for a clinically beneficial change in pain (NNTB = 3.67). Using the GRADE criteria, pain at follow‐up scored very low, meaning we were very uncertain of the estimate of effect.

Analysis 2.1.

Comparison 2 Treatment versus control (headache) follow‐up, Outcome 1 Pain.

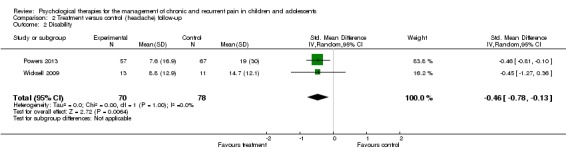

Two studies with 148 participants were included in the analysis to determine the effects of treatment on disability at follow‐up (Powers 2013; Wicksell 2009). Psychological therapies showed a small beneficial effect for reducing disability at follow‐up (SMD ‐0.46, 95% CI ‐0.78 to ‐0.13, z = 2.72, p < 0.01; Analysis 2.2). Similar to disability post‐treatment, we have low confidence in this estimate of effect.

Analysis 2.2.

Comparison 2 Treatment versus control (headache) follow‐up, Outcome 2 Disability.

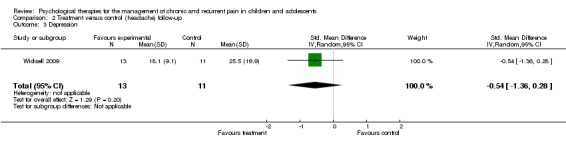

Only one study could be included in the analysis on depression at follow‐up Wicksell 2009, therefore no conclusion could be drawn. We were very uncertain of this estimate of effect.

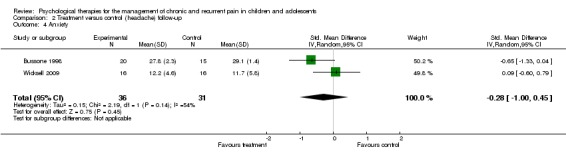

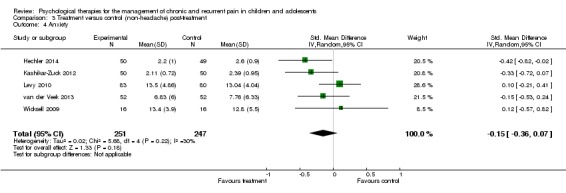

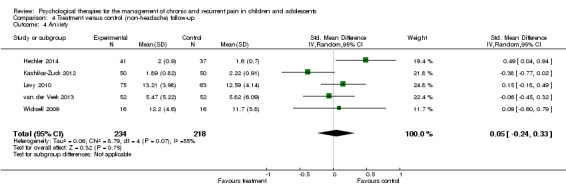

Two studies with 67 participants were entered into an analysis of the effects of treatment on anxiety at follow‐up (Bussone 1998; Wicksell 2009) finding no beneficial effect of psychological therapies (SMD ‐0.28, 95% CI ‐1.00 to 0.45; z = 0.75, p > 0.05; Analysis 2.4).

Analysis 2.4.

Comparison 2 Treatment versus control (headache) follow‐up, Outcome 4 Anxiety.

Treatment versus control (non‐headache) post‐treatment

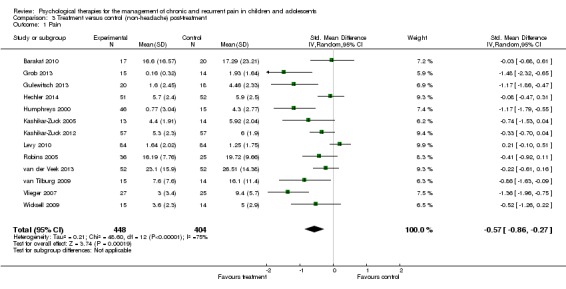

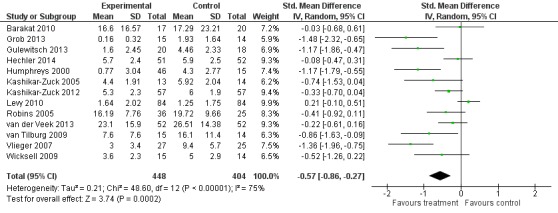

Thirteen studies of 852 participants were entered into an analysis of the effects of psychological treatment on continuous pain outcomes immediately post‐treatment (Barakat 2010; Grob 2013; Gulewitsch 2013; Hechler 2014; Humphreys 2000; Kashikar‐Zuck 2005; Kashikar‐Zuck 2012; Levy 2010; Robins 2005; van der Veek 2013; van Tilburg 2009; Vlieger 2007; Wicksell 2009). Psychological therapies had a medium size beneficial effect on pain (SMD ‐0.57, 95% CI ‐0.86 to ‐0.27, z = 3.74, p < 0.01; Analysis 3.1; Figure 6). According to the GRADE criteria for assessing quality of outcomes, pain post‐treatment scored very low quality, meaning we were very uncertain of the estimate of effect.

Analysis 3.1.

Comparison 3 Treatment versus control (non‐headache) post‐treatment, Outcome 1 Pain.

Figure 6.

Forest plot of comparison: 3 Treatment versus control (non‐headache) post‐treatment, outcome: 3.1 Pain.

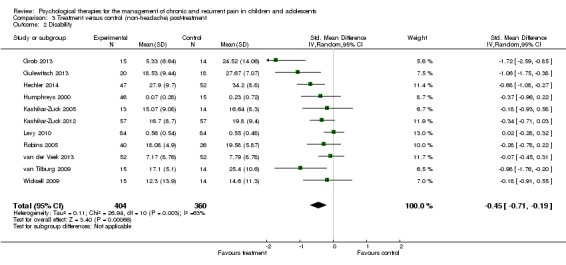

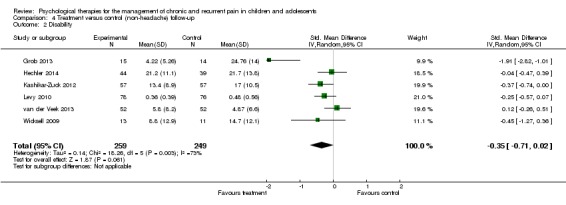

Eleven studies with 764 participants were entered into analysis of the effects of treatment on disability (Grob 2013; Gulewitsch 2013; Hechler 2014; Humphreys 2000; Kashikar‐Zuck 2005; Kashikar‐Zuck 2012; Levy 2010; Robins 2005; van der Veek 2013; van Tilburg 2009; Wicksell 2009). Psychological therapies had a small beneficial effect on reducing disability for children with chronic pain (SMD ‐0.45, 95% CI ‐0.71 to ‐0.19, z = 3.40, p < 0.01; Analysis 3.2). However, we were very uncertain of this estimate of effect.

Analysis 3.2.

Comparison 3 Treatment versus control (non‐headache) post‐treatment, Outcome 2 Disability.

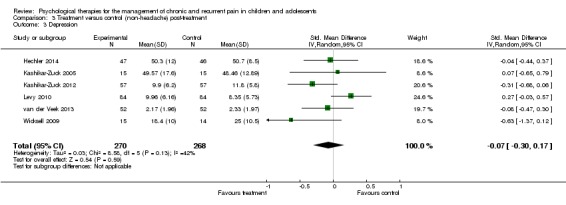

Six studies with 538 participants were entered into analysis of the effects of treatment on depression (Hechler 2014; Kashikar‐Zuck 2005; Kashikar‐Zuck 2012; Levy 2010; van der Veek 2013; Wicksell 2009). The analysis revealed no beneficial effect of psychological therapies on depression (SMD ‐0.07, 95% CI ‐0.30 to 0.17, z = 0.54, p > 0.05; Analysis 3.3). We were moderately confident in the estimate of effect, meaning further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect.

Analysis 3.3.

Comparison 3 Treatment versus control (non‐headache) post‐treatment, Outcome 3 Depression.

Five studies including 498 participants were entered into an analysis to determine the effects of treatment on anxiety immediately post‐treatment (Hechler 2014; Kashikar‐Zuck 2012; Levy 2010; van der Veek 2013; Wicksell 2009). The results revealed no beneficial effect of psychological therapies on anxiety in children with chronic pain (SMD ‐0.15, 95% CI ‐0.36 to 0.07, z = 1.33, p > 0.05; Analysis 3.4). Similar to depression, we were moderately confident in the estimate of effect.

Analysis 3.4.

Comparison 3 Treatment versus control (non‐headache) post‐treatment, Outcome 4 Anxiety.

Of the 17 non‐headache studies, four reported adverse events. Gulewitsch 2013, Kashikar‐Zuck 2012, and van der Veek 2013 reported no adverse events that were study‐related. Wicksell 2009 reported that two participants withdrew due to adverse effects of amitriptyline, which was part of the study condition.

Treatment versus control (non‐headache) follow‐up

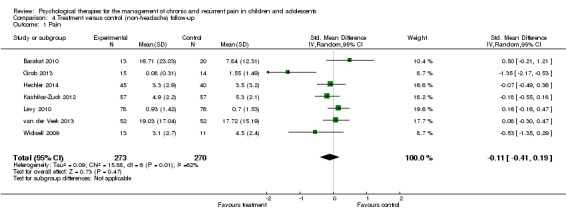

Seven studies of 543 participants had data available for analysis of the effects of treatment on pain at follow‐up (Barakat 2010; Grob 2013; Hechler 2014; Kashikar‐Zuck 2012; Levy 2010; van der Veek 2013; Wicksell 2009). Analysis revealed no beneficial effect for psychological therapies on pain at follow‐up (SMD ‐0.11, 95% CI ‐0.41 to 0.19, z = 0.73, p > 0.05; Analysis 4.1). The quality of outcome was low for this outcome, meaning further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect.

Analysis 4.1.

Comparison 4 Treatment versus control (non‐headache) follow‐up, Outcome 1 Pain.

Six studies of 508 participants were entered into an analysis of the effects of treatment on disability (Grob 2013; Hechler 2014; Kashikar‐Zuck 2012; Levy 2010; van der Veek 2013,Wicksell 2009). No beneficial effect was found for psychological therapies on disability at follow‐up (SMD ‐0.35, 95% CI ‐0.71 to 0.02, z = 1.87, p > 0.05; Analysis 4.2). We have low confidence in the estimate of effect.

Analysis 4.2.

Comparison 4 Treatment versus control (non‐headache) follow‐up, Outcome 2 Disability.

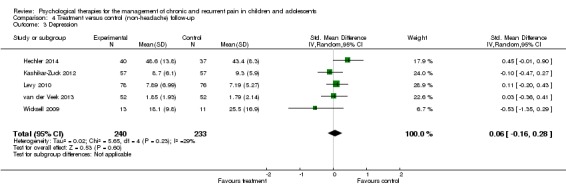

Five studies with 473 participants were entered into an analysis of the effects of treatment on depression (Hechler 2014; Kashikar‐Zuck 2012; Levy 2010; van der Veek 2013; Wicksell 2009). No beneficial effect was found for psychological therapies on depression at follow‐up (SMD 0.06, 95% CI ‐0.16 to 0.28, z = 0.53, p > 0.05; Analysis 4.3). Similar to depression post‐treatment, we were moderately confident in the effect.

Analysis 4.3.

Comparison 4 Treatment versus control (non‐headache) follow‐up, Outcome 3 Depression.

Five studies with 452 participants were entered into an analysis of anxiety at follow‐up (Hechler 2014; Kashikar‐Zuck 2012; Levy 2010; van der Veek 2013; Wicksell 2009). Similar to depression, no beneficial effect was found for psychological therapies on anxiety at follow‐up (SMD 0.05, 95% CI ‐0.24 to 0.33, z = 0.32, p > 0.05; Analysis 4.4).

Analysis 4.4.

Comparison 4 Treatment versus control (non‐headache) follow‐up, Outcome 4 Anxiety.

Discussion

Evidence base

Thirty‐seven studies (end of treatment N = 2111) were included in this updated review. In multi‐arm trials involving more than one treatment or control group, we combined similar treatments or control groups for the purposes of the analyses. The majority of studies used one or two treatment conditions in comparison to a waiting‐list or to a treatment as usual control group. As in the previous review, we categorised treatments as behavioural or cognitive behavioural, although these were combined for all analyses. The average length of treatment in studies of headache conditions and non‐headache studies was very similar, between six and seven hours. Follow‐up data are increasingly being reported in more recent studies and were included when relevant.

The inclusion of further studies has extended the evidence base. Of the 16 possible analyses, psychological therapies were beneficial for seven outcomes. Psychological therapies were beneficial at reducing pain intensity for headache and non‐headache groups post‐treatment, and for the headache group at follow‐up. Fifty‐six per cent of children with headaches reduced their pain scores post‐treatment compared with only 22% in the control groups. Similar findings were demonstrated for disability, for which the findings on disability for the headache group are new to this update. Psychological therapies were beneficial at reducing disability in children with headache pain and non‐headache pain post‐treatment, and for headache groups at follow‐up, although all effect sizes were small. Although we previously found a beneficial effect for treatment effect on mood findings at follow‐up in the headache group (Eccleston 2012), several changes in our protocol have modified this effect. We have now separated mood into depression and anxiety, and have included only trials that delivered treatment face‐to‐face (rather than remotely). Psychological therapies were only found to have a small beneficial effect for anxiety post‐treatment for the headache group. No other beneficial effects were found for depression and anxiety in children with chronic pain.

Pain intensity was the most common treatment outcome assessed, with 15 studies of children with headache and 13 studies of children with non‐headache pain providing data. An NNTB of 2.94 for psychological therapies to produce more than 50% relief in pain in children with headaches was found. An NNTB of 3.67 was found for the smaller number of trials reporting on headache pain at follow‐up. Medium effect sizes were also found for reduction in pain intensity in non‐headache chronic and recurrent pain at post‐treatment. However, the confidence intervals around the effects are large.

Issues for consideration

More recent trials typically use cognitive behavioural therapy rather than behavioural therapy, likely reflecting changes in practice by psychologists entering the field of paediatric pain management.

In regard to pain condition, this review included 20 trials of children and adolescents with headache pain, nine abdominal pain studies, two abdominal pain and irritable bowel syndrome studies, two fibromyalgia studies, two sickle cell disease studies, and two mixed pain studies (including headache and non‐headache pain conditions). There is limited evidence to draw conclusions about the effects of psychological treatment on disability in headache conditions. Although psychological therapies were shown to be beneficial, only three studies could be included in this analysis post‐treatment, and two at follow‐up. There is also limited evidence for treatment affecting depression and anxiety as outcomes. Previously, we reported that mood and disability outcomes in trials of children with chronic pain were an increasing focus for trials (McGrath 2008). This seems still to be the case, and with more studies reporting these outcomes it would be helpful for consensus on the best measurement instruments to be used consistently across the field of paediatric chronic pain, particularly treatment trials.

One limitation of this review is that we are unable to discuss fully the effectiveness of psychological interventions as they were compared with a control group that combined active (e.g. education) and waiting‐list controls. Most studies used active controls, yet we did not feel that it was an appropriate sample to separate for analysis as has been done in a companion review of treatments for adults with pain (Williams 2012). This limitation may contribute to an overestimation of the treatment effects since it is not possible to separate differences specific to treatment versus active treatment or waiting‐list control.

Authors' conclusions

Psychological treatments, principally relaxation and cognitive behavioural therapies delivered face‐to‐face, are effective treatments producing change in pain, disability, and anxiety for children with headache conditions post‐treatment. There is also evidence that the positive changes in pain and disability continue at follow‐up. However, the overall quality of evidence for headache conditions was low/very low, meaning we are not confident in the estimate of effect. Further research is necessary to increase this confidence. Behavioural and cognitive behavioural treatments are also effective in reducing non‐headache pain and disability post‐treatment, but these beneficial effects were not maintained at follow‐up. The quality of outcomes was higher for non‐headache conditions, but further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence of the estimate of effect. There is some evidence to support reductions in anxiety in response to behavioural pain treatment, particularly for children and adolescents with headache conditions at post‐treatment. There is insufficient evidence to comment on the effectiveness of psychological interventions for specific non‐headache pain conditions due to the limited number of studies for each condition, although this has been attempted in a recent review by Fisher 2014.

Taken together, these findings suggest that behavioural treatment should be considered as part of standard care for all children and adolescents with chronic pain. Although there was a small effect for anxiety reduction in children and adolescents with headache conditions at post‐treatment, this was not maintained at follow‐up and there were no effects on depression at either time‐point. This lack of effect may be due to the fact that anxiety and depression are typically not a specific intervention target of cognitive and behavioural pain management interventions.

Since the original version of this review there has been an improvement in the evidence base by the addition of new studies, and the extension into non‐headache pain conditions and treatments that rely on more complex methods. However, this structure limits our understanding of whether psychological therapies are unique in their improvement of symptoms in comparison to active or waiting‐list control groups, yet we judged it important to present combined groups before introducing further analyses. The author team is considering the following changes for the next version of the review.

Increasing the current criterion from 10 to 20 participants in either arm at the point of analysis.

Splitting the title into two: one for headache only and one for non‐headache (e.g. mixed pain conditions).

Exploring the possibility of subgroup analyses to try to identify variance attributable to non‐specific factors which can nevertheless affect treatment outcome, such as type of therapy, dose of therapy, setting of therapy, and therapeutic change agents (e.g. interventions delivered to parents).

Primary research is needed in the following areas.

To establish the efficacy of CBT in outcomes other than pain. In particular, it is important to establish whether CBT can improve mood outcomes and important functional outcomes (such as return to normal schooling), and can reduce the demand for healthcare resources. CBT often has a broad focus beyond pain. Additional pain and non‐pain endpoints are desirable, in particular those relating to mood, disability, and social role functioning (see McGrath 2008).

To establish the efficacy of CBT in non‐headache conditions, in particular idiopathic musculoskeletal pain such as fibromyalgia, and complex regional pain disorders. Randomised controlled trials are possible and desirable.

To establish the efficacy of CBT delivered to and/or via other significant therapeutic change agents such as parents, teachers, or peers. Randomised controlled trials are possible and desirable.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Kiki Mastroyannopoulou and Louise Yorke for their contributions to the original version of this review. Thank you also to Hannah Somhegyi for help with coding and data management during previous versions of this review. Thanks to Jane Hayes and Jo Abbott for running the updated searches. Finally, thanks also go to the PaPaS review group team and to the peer referees for their helpful comments.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

MEDLINE via Ovid search strategy

1. exp child/

2. Infant/

3. Adolescent/

4. (child$ or adolescent$ or infant$ or juvenil$ or pediatric$ or paediatric$ or "young person$" or "young people" or youth$ or "young adult$").ab,it,kf.

5. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4

6. exp Psychology/

7. exp Psychotherapy/

8. exp Behavior Therapy/

9. (psycholog$ or (behavio?r and therapy) or hypnos$ or relaxation$ or ((family or color or colour or music or play) adj therap$) or imagery or cogniti$ or psychotherap$).ab,it,kf.

10. 6 or 7 or 8 or 9

11. (pain$ or headache$ or "head ache$" or head‐ache$ or migraine$ or cephalalgi$ or "stomach ache$" or "tummy ache$" or "abdominal ache$" or "belly ache$" or earache$ or ear‐ache$ or toothache$ or tooth‐ache$ or odontalgi$ or dysmenorrh$ or neuralgi$).ab,it,kf.

12. exp Pain/

13. exp Headache Disorders/

14. 11 or 12 or 13

15. 5 and 10 and 14

16 randomized controlled trial.pt.

17 controlled clinical trial.pt.

18 randomized.ab.

19 placebo.ab.

20 drug therapy.fs.

21 randomly.ab.

22 trial.ab.

23 or/16‐22

24 exp animals/ not humans.sh.

25 23 not 24

26 25 and 15

EMBASE via Ovid search strategy

1. Child/

2. Infant/

3. Adolescent/

4. (child$ or adolescent$ or infant$ or juvenil$ or pediatric$ or paediatric$ or "young person$" or "young people" or youth$ or "young adult$").ab,it.

5. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4

6. exp PSYCHOLOGY/

7. exp PSYCHOTHERAPY/

8. behavior therapy/

9. (psycholog$ or (behavio?r and therapy) or hypnos$ or relaxation$ or ((family or color or colour or music or play) adj therap$) or imagery or cogniti$ or psychotherap$).ab,it.

10. 6 or 7 or 8 or 9

11. (pain$ or headache$ or "head ache$" or head‐ache$ or migraine$ or cephalalgi$ or "stomach ache$" or "tummy ache$" or "abdominal ache$" or "belly ache$" or earache$ or ear‐ache$ or toothache$ or tooth‐ache$ or odontalgi$ or dysmenorrh$ or neuralgi$).ab,it.

12. exp Pain/

13. exp "Headache and Facial Pain"/

14. 11 or 12 or 13

15. 5 and 10 and 14

16 random$.tw.

17 factorial$.tw.

18 crossover$.tw.

19 cross over$.tw.

20 cross‐over$.tw.

21 placebo$.tw.

22 (doubl$ adj blind$).tw.

23 (singl$ adj blind$).tw.

24 assign$.tw.

25 allocat$.tw.

26 volunteer$.tw.

27 Crossover Procedure/

28 double‐blind procedure.tw.

29 Randomized Controlled Trial/

30 Single Blind Procedure/

31 or/16‐30

32 (animal/ or nonhuman/) not human/

33 31 not 32

34 15 and 33

PsycINFO via OVID

1. (child$ or adolescent$ or infant$ or juvenil$ or pediatric$ or paediatric$ or "young person$" or "young people" or youth$ or "young adult$").ab,it.

2. exp PSYCHOLOGY/

3. exp PSYCHOTHERAPY/

4. behavior therapy/

5. (psycholog$ or (behavio?r and therapy) or hypnos$ or relaxation$ or ((family or color or colour or music or play) adj therap$) or imagery or cogniti$ or psychotherap$).ab,it.

6. 2 or 3 or 4 or 5

7. (pain$ or headache$ or "head ache$" or head‐ache$ or migraine$ or cephalalgi$ or "stomach ache$" or "tummy ache$" or "abdominal ache$" or "belly ache$" or earache$ or ear‐ache$ or toothache$ or tooth‐ache$ or odontalgi$ or dysmenorrh$ or neuralgi$).ab,it.

8. exp Pain/

9. Headache/

10. Migraine Headache/

11. Muscle Contraction Headache/

12. 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11

13. 1 and 6 and 12

14 clinical trials/

15 (randomis* or randomiz*).tw.

16 (random$ adj3 (allocat$ or assign$)).tw.

17 ((clinic$ or control$) adj trial$).tw.

18 ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj3 (blind$ or mask$)).tw.

19 (crossover$ or "cross over$").tw.

20 random sampling/

21 Experiment Controls/

22 Placebo/

23 placebo$.tw.

24 exp program evaluation/

25 treatment effectiveness evaluation/

26 ((effectiveness or evaluat$) adj3 (stud$ or research$)).tw.

27 or/14‐26

28 13 and 27

CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library)

#1 MeSH descriptor: [Child] explode all trees

#2 MeSH descriptor: [Infant] explode all trees

#3 MeSH descriptor: [Adolescent] explode all trees

#4 (child* or adolescent* or infant*or juvenil* or pediatric* or paediatric* or "young person*" or "young people" or youth* or "young adult*"):it,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched)

#5 #1 or #2 or #3 or #4

#6 MeSH descriptor: [Psychology] explode all trees

#7 MeSH descriptor: [Psychotherapy] explode all trees

#8 MeSH descriptor: [Behavior Therapy] explode all trees

#9 (psycholog* or (behavio?r and therapy) or hypnos* or relaxation* or ((family or color or colour or music or play) next therap*) or imagery or cogniti* or psychotherap*):it,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched)

#10 #6 or #7 or #8 or #9

#11 (pain* or headache* or "head ache*" or head‐ache* or migraine* or cephalalgi* or "stomach ache*" or "tummy ache*" or "abdominal ache*" or "belly ache*" or earache* or ear‐ache* or toothache* or tooth‐ache* or odontalgi* or dysmenorrh* or neuralgi*):it,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched)

#12 MeSH descriptor: [Pain] explode all trees

#13 MeSH descriptor: [Headache Disorders] explode all trees

#14 #11 or #12 or #13

#15 #5 and #10 and #14

Appendix 2. Previous search results

Four separate searches have been undertaken. The first search was undertaken from inception of the abstracting services to the end of 1999 (Eccleston 2003a). This yielded 3715 abstracts, of which 123 were read in full, identifying 18 RCTs. The second search, which updated the original review, was undertaken focusing on the 10 years since the previous search, overlapping by one year (from 1999 to 2008) and was later published (Eccleston 2009). This yielded 1319 abstracts, of which 45 papers were read in full, identifying a further 16 RCTs, giving a total set of 34. However, five studies were later excluded because they did not meet the minimum criteria of 10 participants in each arm, therefore, leaving 29 studies. The third, which searched databases from 2008 to March 2012 yielded 851 abstracts, of which 25 papers were read in full, and eight further RCTs were included in the review (Eccleston 2012). The fourth searched databases from March 2012 to January 2014 yielding 443 abstracts, of which 19 were read in full, and seven papers were included (Grob 2013; Gulewitsch 2013; Hechler 2014; Kashikar‐Zuck 2012; Levy 2010; Powers 2013; van der Veek 2013). Kashikar‐Zuck 2012 and Levy 2010 provided additional data to previously included studies. Five studies, which were previously included, were excluded from this review since treatment was delivered remotely (Connelly 2006; Hicks 2006; Palermo 2009; Stinson 2010; Trautmann 2010). Therefore, a total of 37 RCTs are included (39 papers).

Data and analyses

Comparison 1.

Treatment versus control (headache) post‐treatment

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Pain | 15 | 714 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.47 [1.97, 3.09] |

| 2 Disability | 3 | 263 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.49 [‐0.74, ‐0.24] |

| 3 Depression | 3 | 164 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.18 [‐0.49, 0.14] |

| 4 Anxiety | 4 | 203 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.33 [‐0.61, ‐0.04] |

Comparison 2.

Treatment versus control (headache) follow‐up

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Pain | 5 | 251 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.89 [1.03, 8.07] |

| 2 Disability | 2 | 148 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.46 [‐0.78, ‐0.13] |

| 3 Depression | 1 | 24 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.54 [‐1.36, 0.28] |

| 4 Anxiety | 2 | 67 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.28 [‐1.00, 0.45] |

Analysis 2.3.

Comparison 2 Treatment versus control (headache) follow‐up, Outcome 3 Depression.

Comparison 3.

Treatment versus control (non‐headache) post‐treatment

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Pain | 13 | 852 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.57 [‐0.86, ‐0.27] |

| 2 Disability | 11 | 764 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.45 [‐0.71, ‐0.19] |

| 3 Depression | 6 | 538 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.07 [‐0.30, 0.17] |

| 4 Anxiety | 5 | 498 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.15 [‐0.36, 0.07] |

Comparison 4.

Treatment versus control (non‐headache) follow‐up

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Pain | 7 | 543 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.11 [‐0.41, 0.19] |

| 2 Disability | 6 | 508 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.35 [‐0.71, 0.02] |

| 3 Depression | 5 | 473 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.06 [‐0.16, 0.28] |

| 4 Anxiety | 5 | 452 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.05 [‐0.24, 0.33] |

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 9 February 2016 | Review declared as stable | See Published notes. |

History

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 14 May 2014 | Amended | Minor change to the GRADE assessment wording. |

| 30 April 2014 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | A new search was run in January 2014. |

| 14 March 2014 | New search has been performed | Five new studies were added. Two trials containing additional information for previously included studies were included. Five studies that were previously included were excluded as they delivered treatment remotely. These will be included in the new Cochrane review ('Psychological therapies (remotely delivered) for the management of chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents'). 'Mood' outcome was split into two discrete domains; anxiety and depression. |

| 21 August 2013 | Amended | 'Summary of findings' tables have been updated. |

| 24 October 2012 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | The previous review reported that psychological treatments were effective for headache and non‐headache groups at post‐treatment and effects were maintained at follow‐up. Updated studies have altered the previous results. The current update found that pain improved at post‐treatment for headache and non‐headache groups, and for headache groups at follow‐up. An additional significant finding for disability at post‐treatment for the non‐headache group was found. Conclusions have been updated accordingly. |

| 24 October 2012 | New search has been performed | New authors have been added to this review. A new search was run in March 2012. Eight new studies were added (Barakat 2010; Kashikar‐Zuck 2012; Levy 2010; Palermo 2009; Stinson 2010; Trautmann 2010; van Tilburg 2009; Wicksell 2009), and four new studies were excluded (Trautmann 2008; Vlieger 2012; Weydert 2006; Youssef 2009). |

| 16 May 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Differences between protocol and review

In Eccleston 2009, odds ratios and risk ratios were reported for dichotomous outcomes. In this review we only report risk ratio.

In this review, therapy that was delivered remotely (e.g. via Internet, telephone) has been removed and the 'mood' outcome has been separated into two discrete outcomes: depression and anxiety.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]