Abstract

Percutaneous native renal biopsy is recognized as a safe procedure. The majority of bleeding events occur within 24 h after the procedure, and reports of delayed major complications are very limited. We report a patient presenting with sudden flank pain 7 days after renal biopsy, in whom abdominal computed tomography showed increased hematoma size with extravasation and who was treated with radiological intervention. Careful attention should be paid to diagnose and treat delayed major complications in patients undergoing native renal biopsy.

Keywords: Renal biopsy, Complications, Hematoma, Intervention, Guidelines

Introduction

Percutaneous native renal biopsy is recognized as a safe procedure when performed with real-time ultrasound guidance and automated needle devices. Hematoma is one of the most common complications. Eighty-nine percent of all complications occur within 24 h of the procedure [1]. Bleeding complications requiring blood transfusion or radiological or surgical intervention occurring 24 h or more after the procedure represented 0.28% of all complications in a recent retrospective study [2]. Although the safety and effectiveness of same-day, outpatient renal biopsy were advocated [3], the optimal observation period before discharge after renal biopsy remains debated. Currently, the establishment of practical guidelines for renal biopsy performance is urgently needed [4]. To provide the optimal observation period, clinical data concerning late-onset complications is necessary, in addition to data on early complications. However, reports of delayed bleeding several days after renal biopsy are very limited. Here, we report a patient who developed serious post-procedure bleeding requiring angiographic embolization, diagnosed by computed tomography (CT) 7 days after renal biopsy.

Case report

A 42-year-old Japanese man with a history of obesity and diabetes mellitus presented to our hospital for evaluation of persistent proteinuria. He took no medications, including antithrombotics. His vital signs at first presentation were normal. His height was 173 cm and his weight was 91 kg. Fundoscopic examination showed simple diabetic retinopathy. Laboratory findings showed a serum albumin level of 4.2 g/dL, blood urea nitrogen level of 11.1 mg/dL, serum creatinine level of 0.98 mg/dL (estimated glomerular filtration rate of 67.8 mL/min/1.73 m2), hemoglobin A1c level of 5.7%, hemoglobin concentration of 15.8 g/dL, platelet count of 23.9 × 104/uL, international normalized ratio/prothrombin time of 1.02, and activated partial thromboplastin time of 30.0 s. Urinalysis revealed a urine protein level of 2.9 g/day and urine red blood cell count of 11–20/high-power field. After preparing his skin in a sterile fashion, he underwent ultrasound-guided biopsy of the left kidney with a 16-gauge automated, spring-loaded needle (Tru-Core II, Angiotech Pharmaceuticals Inc., Gainesville, FL, USA). The procedure was uneventful and his vital signs remained stable. After the procedure, we prescribed bed rest in a supine position using an abdominal compression belt for 4 h and monitored his vital signs. One day later, routine abdominal CT showed a small hematoma (Fig. 1, 111 mL, measured using imaging software (Ziostation 2, Ziosoft, Tokyo, Japan)). After careful observation for 48 h, he was discharged with no signs or symptoms. Light microscopy sections contained 25 glomeruli, three of which were globally sclerotic, with no punctured large arterioles. The remaining glomeruli showed mild increase in mesangial matrix without hypercellularity. Interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy was estimated at 20%. Combined with presence of arteriolar hyalinosis, the histological findings were consistent with diabetic nephropathy class IIa, according to the criteria of the Renal Pathology Society [5].

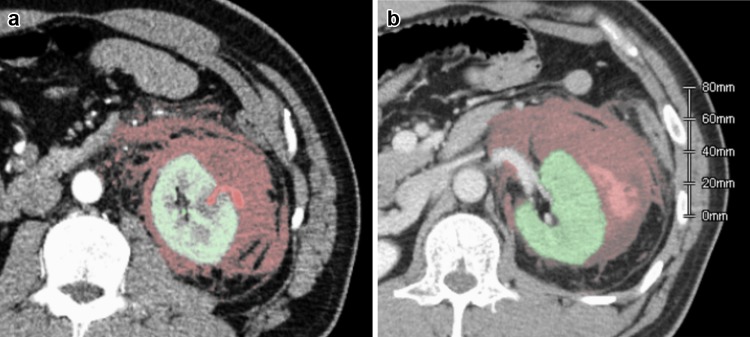

Fig. 1.

Transverse non-contrast computed tomography (CT) image demonstrated a tiny retroperitoneal hematoma 1 day after left renal biopsy. A hematoma volume of 111 mL, illustrated as the red-colored area, was measured using reconstructed CT data

Seven days after the biopsy, he returned to the emergency room with sudden left abdominal pain, with no history of trauma noted. His vital signs showed a blood pressure of 174/110 mmHg, heart rate of 78 bpm, and respiratory rate of 24 bpm. Percussion tenderness of the left abdomen was present. Electrocardiogram showed a sinus pattern. Laboratory findings showed a lactate dehydrogenase level of 184 U/L, serum creatinine level of 1.12 mg/dL, and hemoglobin concentration of 14.4 g/dL.

CT scan with contrast showed increased size of the hematoma and clear extravasation protruding from the renal parenchyma in the region corresponding to the biopsy site (Fig. 2a, b, 955 mL). We performed angiographic embolization with coiling (Fig. 3a, b). A microcatheter (2.8 Fr, Masters Parkway; Asahi Intecc., Japan) was advanced to the lower branch of the left renal artery and four Tornado microcoils (2 × 3 mm, Cook Medical, USA) were deployed near the region of extravasation. After we confirmed the absence of further extravasation, his abdominal pain was gradually alleviated and he was discharged from our hospital 8 days later.

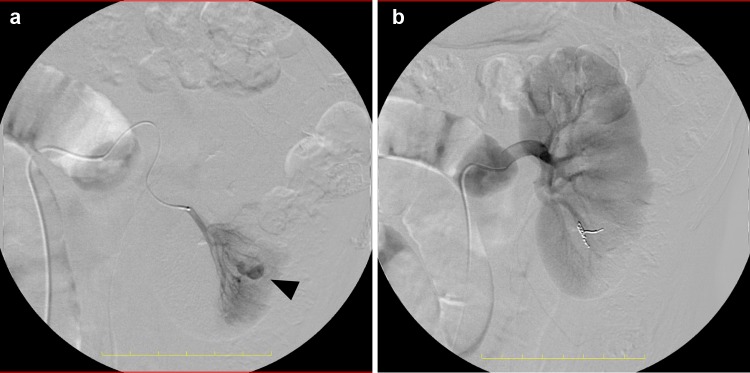

Fig. 2.

Computed tomography (CT) image with contrast to examine the cause of sudden flank pain 7 days after the procedure. As shown in an arterial phase, expansion of the hematoma was explained by the extravasation protruding outward from the renal parenchyma (a). At the equilibrium phase, the contrast was viewed within the hematoma, representing active bleeding (b). A hematoma volume of 955 mL, shown as the red-colored area, was measured using reconstructed CT data

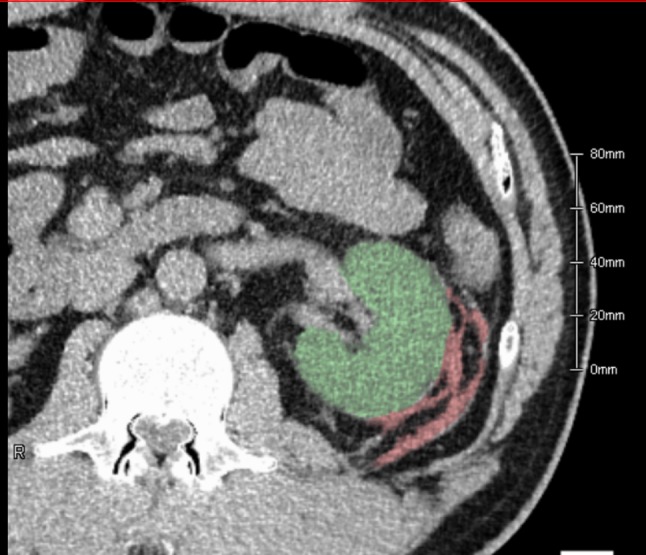

Fig. 3.

Angiographic image demonstrated expansive bleeding from the renal parenchyma, corresponding to the biopsy site. The pseudoaneurysm (arrowhead) equivalent to arterial-venous fistula was identified (a). Blood supply to the periphery of the renal artery was completely occluded with deployment of microcoils (b)

Discussion

We report a patient who developed major bleeding 7 days after percutaneous native renal biopsy. This case provides reliable evidence that biopsy-related delayed bleeding could result in serious complications.

Major complications associated renal biopsy that require radiological intervention are rare. However, massive bleeding leading to bladder obstruction and requiring blood transfusions and/or radiological or surgical intervention are important to consider in patients undergoing the procedure [4]. Despite the technical improvements with the use of ultrasound guidance and automated biopsy devices, major complications occur in up to 8.0% of patients, and the major complications requiring radiological intervention occur in up to 1.2% according to a recent editorial [6]. In our patient, delayed major bleeding requiring radiological intervention developed despite the fact that the patient was asymptomatic during the initial hospital stay. Predictors of major bleeding such as coagulopathy, kidney dysfunction (serum creatinine, less than 2.0 mg/dL), low hemoglobin concentration, use of a wide needle (i.e. 14 gauge), or atherosclerosis [4, 7] were not identified in this patient. While considered to have relatively low risk, the patient unfortunately developed delayed major bleeding without any history of trauma 7 days after the procedure.

Over 90% of biopsy-related complications occur within 24 h after the procedure [1]. Recently, there have been several reports advocating the safety and effectiveness of same-day, outpatient renal biopsy, in which patients are monitored for less than 8 h postoperatively [3]. However, given that the observation period is 8 h, 33% of all complications would be missed [1]. Korbet et al. recommend that we should monitor patients at least 24 h after the procedure [6]. However, reliable reports on delayed major complications developing after discharge are very limited. Regarding concise clinical data of delayed complications, there are only a few lines described in several published case series [1, 2, 8, 9]. One reason for the paucity of data on delayed complications is because it is difficult to accurately determine the etiology of the bleeding event when it occurs after a long delay. Furthermore, due to publication bias of retrospective studies, not all delayed events can be identified, and the number of events is thus potentially underestimated.

Evidence-based standards of renal biopsy performance have been established in several countries [4]. To optimize the monitoring period after the procedure, reliable case reports must be accumulated. The current Japanese guideline for renal biopsy [10] reports the potential occurrence of delayed bleeding several days after the procedure and prohibits strenuous activities for several months; however, these parts of the guideline are based on insufficient evidence. Our case report is clinically relevant, because sequential CT scans revealed that the renal biopsy was the underlying etiology of the bleeding event 7 days after the procedure.

Together, this case report, in which the patient was asymptomatic immediately after the procedure but developed delayed major bleeding, provides useful data for determining the optimal time length after native renal biopsy.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Takashi Hakamatsuka, a radiologist at our institute, for a fruitful discussion on the radiological intervention, and Keisuke Osamoto, a radiology technician at our institute, for accurate measurement of the hematoma volumes using imaging software.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Human and animal rights

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

References

- 1.Whittier WL, Korbet SM. Timing of complications in percutaneous renal biopsy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:142–147. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000102472.37947.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atwell TD, Spanbauer JC, McMenomy BP, Stockland AH, Hesley GK, Schleck CD, Harmsen WS, Welch TJ. The timing and presentation of major hemorrhage after 18,947 image-guided percutaneous biopsies. Am J Roentgenol. 2015;205:190–195. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.13002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maya ID, Allon M. Percutaneous renal biopsy: outpatient observation without hospitalization is safe. Semin Dial. 2009;22:458–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2009.00609.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hogan JJ, Mocanu M, Berns JS. The native kidney biopsy: update and evidence for best practice. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11:354–362. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05750515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tervaert TW, Mooyaart AL, Amann K, Cohen AH, Cook HT, Drachenberg CB, Ferrario F, Fogo AB, Haas M, de Heer E, Joh K, Noël LH, Radhakrishnan J, Seshan SV, Bajema IM, Bruijn JA. Renal Pathology Society. Pathologic classification of diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:556–63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Korbet SM. Nephrology and the percutaneous renal biopsy: a procedure in jeopardy of being lost along the way. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7:1545–1547. doi: 10.2215/CJN.08290812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanaka K, Kitagawa M, Onishi A, Yamanari T, Ogawa-Akiyama A, Mise K, Inoue T, Morinaga H, Uchida HA, Sugiyama H, Wada J. Arterial stiffness is an independent risk factor for anemia after percutaneous native kidney biopsy. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2017;42:284–293. doi: 10.1159/000477453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishikawa E, Nomura S, Hamaguchi T, Obe T, Inoue-Kiyohara M, Oosugi K, Katayama K, Ito M. Ultrasonography as a predictor of overt bleeding after renal biopsy. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2009;13:32531. doi: 10.1007/s10157-009-0165-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simard-Meilleur MC, Troyanov S, Roy L, Dalaire E, Brachemi S. Risk factors and timing of native kidney biopsy complications. Nephron Extra. 2014;4:42–49. doi: 10.1159/000360087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishi S. Series of guidebook of renal biopsy: IV. Prescription of bed-rest after renal biopsy. Nippon Jinzo Gakkai Shi. 2005;47:491–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]