Abstract

The N-butyl-N-(4-hydroxybutyl)-nitrosamine (BBN) mouse model is an attractive model system of muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) as it recapitulates the histology of human tumors in a background with intact immune system. However, it was unknown whether this carcinogen-induced model also mimicked human MIBC at the molecular and mutational level. In our study, we analyzed gene expression and mutational landscape of the BBN model by next-generation sequencing followed by a bioinformatic comparison to human MIBC using data from The Cancer Genome Atlas and other repositories. BBN tumors showed overexpression of markers of basal cancer subtype, and had a high mutation burden with frequent Trp53 (80%), Kmt2d (70%), and Kmt2c (90%) mutations by exome sequencing, similar to human MIBC. Many variants corresponded to human cancer hotspot mutations, supporting their role as driver mutations. We extracted two novel mutational signatures from the BBN mouse genomes. The integrated analysis of mutation frequencies and signatures highlighted the contribution of aberrations to chromatin regulators and genetic instability in the BBN tumors. Together, our study revealed several similarities between human MIBC and the BBN mouse model, providing a strong rationale for its use in molecular and drug discovery studies.

Introduction

Bladder cancer is the fourth most common cancer in men and fifth most common malignancy in the US [1]. The male-to-female bladder cancer incidence ratio is about 2.2:1, with no histological differences observed between the sexes [2]. Survival of patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) is poor, with only 35% survival at 5 years in lymph node-positive tumors [3, 4]. Therefore, alternatives to the standard cisplatin-based chemotherapy are in high demand. Immune checkpoint inhibitors were recently approved for MIBC treatment and showed promising results, but only a fraction of patients responded and the mechanisms underlying drug sensitivity are not fully understood yet [5, 6]. Developing more effective anticancer drugs relies on the availability of animal model systems that closely recapitulate the corresponding human disease. One of the major limitations in the field of bladder cancer research is the limited availability of such models [7].

The work of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) network recently unveiled the major genetic determinants of MIBC, and showed that bladder cancer can be further subclassified at the molecular level according to gene expression and mutational patterns [8, 9]. Molecular classification of cancer is anticipated to guide therapeutic intervention in a patient-specific fashion, and it was shown that molecular profiling of urothelial cancer cell lines could predict sensitivity to cisplatin [10]. To overcome the limited clinical translatability of results based on tumor-derived cell lines [11], animal models of cancer are used. Patient-derived xenografts (PDX)-based models are a valid complement to the use of cell lines [12], but have shortcomings, including the incompatibility with immunocompetent mice [13]. Genetically engineered mice (GEMs) have been successfully used to replicate several human cancers, including bladder cancer. For example, the combined deletion of Trp53 and Pten in mice resulted in invasive bladder tumors [14]. However, GEMs rarely replicate the heterogeneity and high mutation load of human cancers [7].

Currently, an attractive system for modeling MIBC is the N-butyl-N-(4-hydroxybutyl)-nitrosamine (BBN) model. BBN is a nitrosamine alkylating compound closely related to some of the carcinogens found in cigarette smoke. BBN specifically affects the bladder, resulting in the development of invasive tumors by 5 months [15]. BBN-induced tumors are unifocal or less frequently multifocal, and may have papillary, squamous, or basal-cell histology [16], mimicking the morphological spectrum of human MIBC. However, it was unknown whether the BBN-induced tumors reflected the molecular and mutational aberrations of human bladder cancer.

In this study we characterized the molecular alterations of the BBN model via RNA-seq and whole exome sequencing (WES), along with an integrative analysis of genetic alterations and mutational signatures to compare this mouse model with human MIBC.

Results

Gene expression dysregulation in BBN tumors

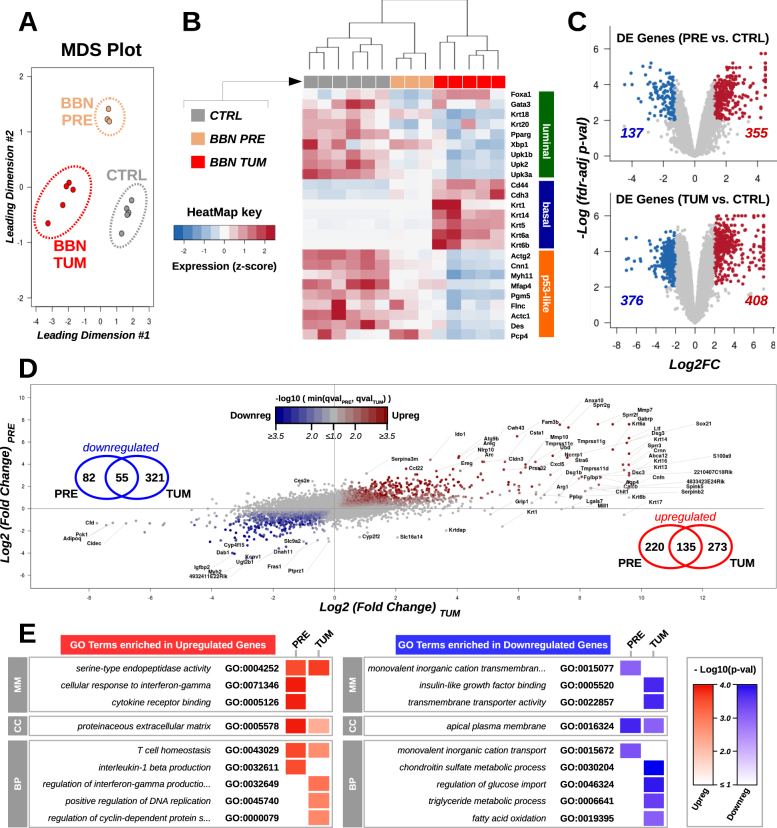

To determine how closely molecular alterations of BBN-induced urothelial carcinomas aligned with human bladder cancer, we performed RNA-seq and WES analyses (supplementary figure S1A). Male C57BL/6 mice were treated with BBN for 20 weeks and all developed invasive tumors with histological features similar to what reported before [17–19] (supplementary figure S1B). We compared gene expression in normal bladders, precancerous bladders from mice exposed to BBN for 4 weeks, and bladders with tumor by RNA-seq. Multidimensional scaling analysis of gene expression data revealed three distinct clusters matching the BBN treatment groups (Fig. 1a). Next, we examined expression levels of subtype-specific markers [20], and found that BBN tumors had a basal expression profile, with increased expression of Cd44, Cdh3, and Krt14 (Fig. 1b). Our results were consistent with previous reports showing BBN-induced Krt5 [17] (Fig. 1b) and cyclins [21] upregulation (supplementary figure S2A). Genes aberrantly expressed in precancerous- (upregulated, n = 355; downregulated, n = 137) and BBN tumor- (upregulated, n = 408; downregulated, n = 376) bladders (Fig. 1c) were further compared (upregulated, n = 135; downregulated, n = 55) showing a partial overlap (Fig. 1d). Specifically, gene ontology (GO) enrichment analyses showed that genes related to T-cell homeostasis (Il7r/, Il2ra, Ripk3) or encoding for extracellular regulatory molecules (Wnt10a, Cxcl5, Mmp7) were consistently dysregulated at both early and late BBN treatment times, while aberrant expression of cell-cycle- (upregulation of Ccna2, Cdkn2a, Plk1) and metabolism-related pathways (downregulation of Pdk4, Abcd2, Lep) was only detected in the established BBN tumors (Fig. 1e and supplementary figure S2B). Altogether, our RNA-seq analyses suggested that BBN treatment affected gene expression in pre-cancerous bladders activating immune-related pathways, and promoted a basal cancer subtype expression program in the bladder tumors, with dysregulation of specific cell-cycle and metabolic gene sets.

Fig. 1.

Gene expression profiles of BBN bladder tumors. a Gene expression in normal bladders (CTRL, gray, n = 6), precancerous bladders from mice exposed to BBN for 4 weeks (BBN PRE, gold, n = 3), and bladders with tumor (BBN TUM, red, n = 5) was assessed by RNA-seq followed by multidimensional scaling analysis. b Heatmap showing expression levels (median-based z-scores) of a list of markers of luminal-, basal-, and p53-like molecular cancer subtypes in bladder samples. c Volcano plots highlighting genes over- (red) and under- (blue) expressed in pre-cancerous (top) or tumoral (bottom) samples compared to control bladders. The number of differentially expressed genes in precancerous bladders and in the BBN tumors is reported. d Scatter plot of gene expression fold changes in the precancerous bladders against controls (y-axis) compared to BBN tumors against controls (x-axis). Point color tracks with the negative logarithm of the bigger false discovery rate (fdr)-adjusted p-value associated with the corresponding gene in the pre-cancerous bladder or in the BBN tumors against controls. Venn diagrams indicate the number of genes consistently up or downregulated. e Heatmap summarizing GO terms enriched in the lists of differentially expressed genes in the pre-cancerous and tumor samples against controls. Color intensity tracks with the negative logarithm of the corresponding p-value (classic Fisher’s exact test)

Mutational landscape of BBN tumors

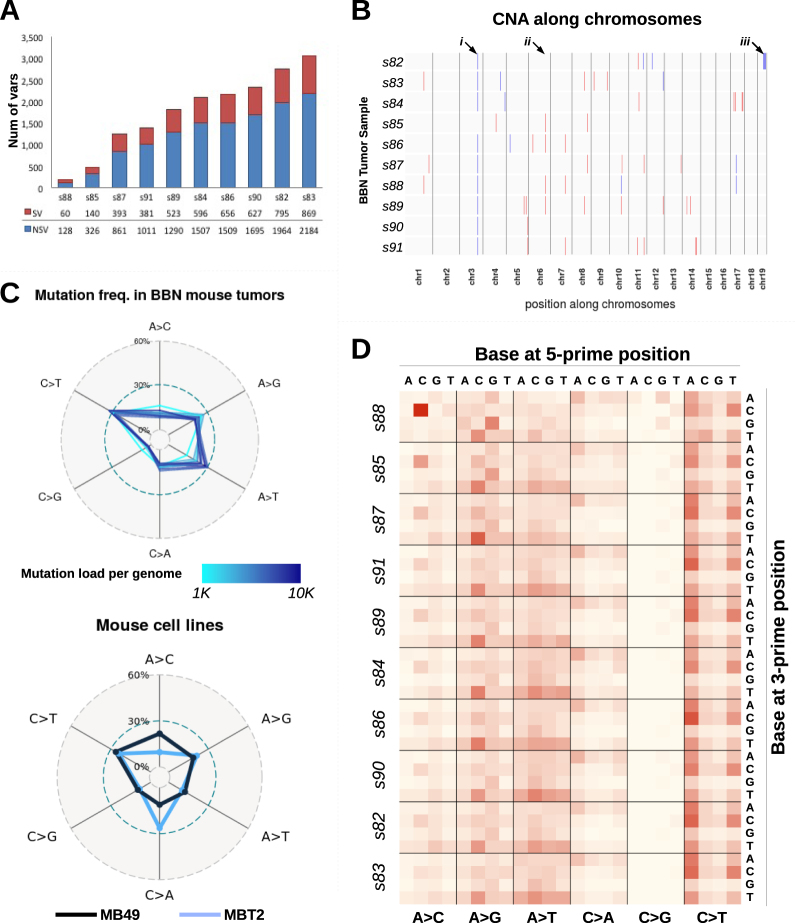

We analyzed BBN tumor genomes by WES. The total number of mutations per tumor spanned from 128 to 2184 non-synonymous variants (NSVs) (Fig. 2a), corresponding to somatic mutations rates from 0.62 to 4.93 mutations per megabase (Mb) with a median of 3.2 variants/Mb, which is comparable to the mutation range detected in human bladder tumors by the TCGA consortium (median = 5.5 variants/Mb) [8]. WES data were analyzed using Control-FREEC [22], showing no major chromosomal copy number alteration (CNA), nor consistent focal indel at known cancer-related loci across tumors (Fig. 2b and supplementary figures S3 and S4). We further examined WES data and found that BBN tumors mainly accumulated C>T and A>G transitions (Fig. 2c), similar to what found in bladder cancers from the TCGA and the Dana_Farber_&_MSKCC_2014 [23] datasets (supplementary figure S5A). Compared to human tumors from these repositories, BBN tumors had a reduced frequency of C>G transversions and increased frequency of A>T transversions. Interestingly, high frequency of A>T mutations was reported before in human urothelial carcinomas from patients exposed to aristolochic acid [24] or with transcription-coupled nucleotide excision repair (tc-NER) defects [25]. Some of these genomes were available in the BGI_2013 [26] dataset (supplementary figure S5B), and had a pattern of mutation frequencies similar to the BBN tumors. Interestingly, we also observed that in BBN tumors, the relative frequency of A>T transversions correlated with mutation load (Fig. 2c and supplementary figure S5C). Genomic DNA from two common mouse urothelial cancer cell lines, MBT2 and MB49, was also analyzed by WES. These cell lines were obtained from FANFT-induced mouse tumors and DMBA-exposed mouse bladder explants respectively [27] and their mutational profiles showed important differences compared to either mouse or human tumors (Fig. 2c). The frequency of mutations within the tri-nucleotidic context was also explored in the BBN tumors (Fig. 2d) and mouse cell lines (supplementary figure S5D). This confirmed the differences between mouse tumors and cell lines, and revealed a conserved pattern of mutation ratios across BBN tumors, with few inter-tumor differences correlated to mutation load.

Fig. 2.

Mutation profiles of BBN bladder tumors. a All mice (n = 10) treated with BBN for 20 weeks developed bladder tumors. After sacrifice, genomic DNA was extracted from the tumor-containing bladders, and then submitted for sequencing. Bars indicate the number of variants identified in each mouse tumor, including both synonymous (SV, red) and non-synonymous (NSV, blue) mutations. b Plot summarizing copy number alterations (CNA) identified in the BBN tumor genomes by Control-FREEC analysis. Blue regions indicate DNA losses, red regions indicate DNA gains. Major or consistent CNA are highlighted by arrows: (i) chr3: affecting Sec24d gene; (ii) chr6: affecting Slc6a11 gene; (iii) a shallow deletion of chr19qC3 was detected in only one tumor, s82. c Frequencies of nucleotide conversion for each BBN tumor (top) and two mouse bladder cell lines (bottom) are displayed in the radar charts. Line color corresponds to mutation load (top) or identifies the cell line (bottom). d Frequency of nucleotide conversions within the tri-nucleotide context is displayed in the heat map. Conversions are grouped by mutation type (A>C, A>G, A>T, C>A, C>G, C>T), with different 5′ bases organized column-wise and 3′ bases organized row-wise. Samples are ordered according to mutation load, revealing specific mutations that are directly (i.e., N[A>T]T) or inversely (i.e., C[A>C]C, G[A>G]G) correlated with mutation load

Mutational signatures identified in BBN tumors

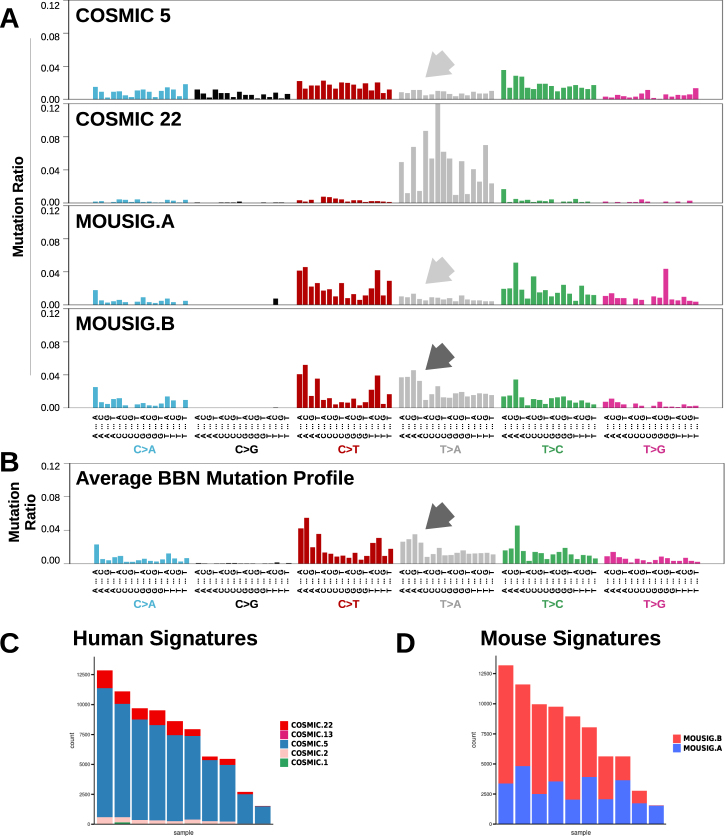

Mutational signatures extracted from tumor genomes can provide valuable insights into the biological processes responsible for genetic instability in cancer. In human MIBC genomes, 4 “Catalog Of Somatic Mutations In Cancer”- (COSMIC) mutational signatures were identified (supplementary figure S6A and [28]). These included signatures COSMIC-2 and COSMIC-13 that are linked to the activity of APOBEC enzymes and signature COSMIC-5 (Fig. 3a) that was found enriched in tumors with defective tc-NER [29]. Recently, mutational catalogs enriched in T>A transversions from human urothelial carcinomas with known exposures to aristolochic acid [30] concurred to define COSMIC-22 signature (Fig. 3a). By combining mutations from all mouse tumors, we obtained an averaged BBN mutation profile similar to COSMIC-5 with the addition of distinct peaks corresponding to T>A mutations (Fig. 3b). By deconvoluting BBN genomes, we found that mutations were explained by only two signatures, COSMIC-5 and COSMIC-22 (Fig. 3c), with the contribution of the latter increasing together with mutation load (supplementary figure S6B). APOBEC-associated mutations were not detected in the mouse tumors. COSMIC signatures were derived from human cancer genomes and may not suit genetic alterations found in carcinogen-induced mouse tumors. Therefore, we also de novo extracted mutational signatures from the BBN tumor genomes using an approach based on the WTSI framework by Alexandrov et al. [28]. This resulted in two mouse-derived signatures, namely MOUSIG-A and MOUSIG-B (Fig. 3a), which mainly differed because of the higher frequency of T>A mutations in MOUSIG-B. BBN genomes deconvolution revealed that all samples had a baseline of MOUSIG-A, with a contribution of MOUSIG-B increasing together with mutation load (Fig. 3d and supplementary figure S6C).

Fig. 3.

Mutational signatures operating in BBN bladder tumors. a Mutational profiles corresponding to COSMIC signatures 5 and 22, and to newly-extracted signatures from mouse BBN-induced tumors, namely MOUSIG-A and MOUSIG-B. Arrows indicate T>A transversions that are absent in signatures COSMIC-5 and MOUSIG-A (light gray arrows), but are enriched in MOUSIG-B (dark gray arrow). Single nucleotide variants were grouped by the tri-nucleotide context. b Aggregated mutational profile of ten BBN tumors. Dark gray arrow indicates a group of T>A transversions matching a mutational pattern from MOUSIG-B signature. Single nucleotide variants were grouped by the tri-nucleotide context. c, d Contributions of COSMIC or de novo extracted MOUSIG mutational signatures to individual tumors. Each bar represents a BBN tumor and the vertical axis denotes the number of mutations imputed to each signature (blue: COSMIC-5 or MOUSIG-A; red: COSMIC-22 or MOUSIG-B)

Intra-tumor heterogeneity of BBN tumors

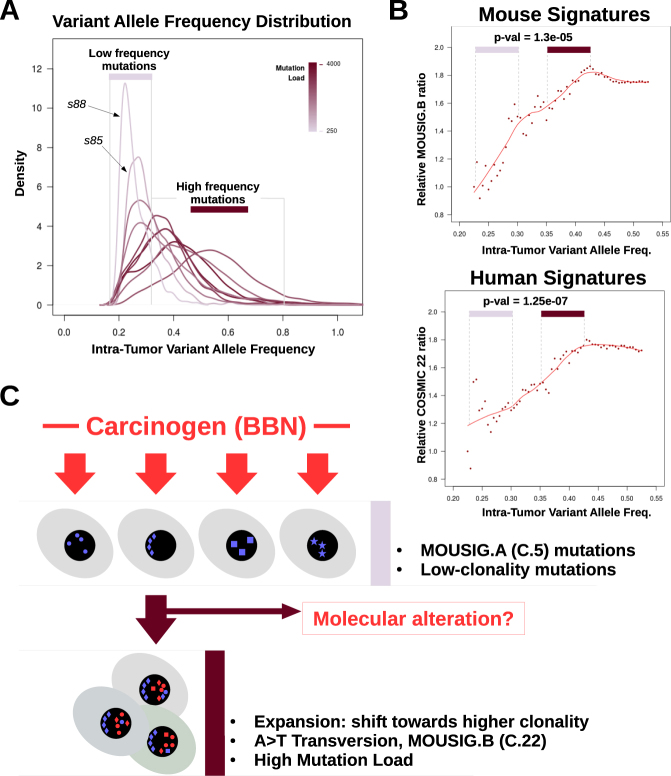

WES data were further analyzed to investigate intra-tumor heterogeneity [31], which is commonly observed in solid tumors due to the presence of different cancer cell subpopulations diverging because of the differential accumulation of DNA mutations [32]. We first estimated tumor ploidy and tumor cellularity, which is the fraction of cancer cells in the tumor. BBN genomes were analyzed using Sequenza [33] and found quasi-diploid (ploidy~2.1), with cellularity ranging from 50 to 60% (supplementary table ST1). These values were consistent with the results of our Control-FREEC analysis (Fig. 2b and supplementary figure S3). Next, we analyzed intra-tumor variant allele frequencies. Carcinogen exposure generates a vast majority of passenger mutations, which do not alter cancer cell fitness [32], and a small set of driver mutations that confer selective growth advantage, sustain clonal expansion, and result in higher variant allele frequencies [34, 35]. Intra-tumor heterogeneity was assessed by analyzing the distribution of cellularity-corrected variant allele frequencies (Fig. 4a and supplementary figure S7). While few tumors (s88, s85) mainly accumulated low-frequency mutations, others had broad distributions of variant allele frequencies, with peaks shifted toward higher frequencies. The extent of such shift tracked with total number of variants per sample (Fig. 4a). Previously, we observed a correlation between mutation load and relative frequency of T>A transversions. Therefore, we hypothesized that accumulation of T>A mutations, gain in mutation load, and increase of intra-tumor mutation frequencies might occur together as result of molecular alterations driving clonal expansion. This hypothesis was supported by the finding that T>A mutations (supplementary figure S8) and T>A-rich mutation signatures (Fig. 4b) were enriched among mutations with high variant allele frequency. These observations supported a model (Fig. 4c) including at least two processes that contributed to genetic instability in the BBN model. The first is an exogenous process, driven by exposure to the carcinogen that induces a wide spectrum of low-frequency mutations corresponding to the MOUSIG-A/COSMIC-5 signature. The second process is responsible for the accumulation of A>T transversions (MOUSIG-B/COSMIC-22 mutations), and is associated with the increase in variant allele frequencies, which is suggestive of clonal expansion as expected in consequence of driver mutations. Mutations of specific bladder-cancer genes might enable the second genetic instability process. This model is consistent with the observation that the mutational profile of mouse bladders exposed to BBN for 4 weeks was depleted in T>A transversions, and matched signature MOUSIG-A/COSMIC-5, with no contribution of MOUSIG-B/COSMIC-22 (supplementary figure S9).

Fig. 4.

Relationship between mutation load and intra-tumor variant allele frequencies in BBN tumors. a Density plot showing the distributions of intra-tumor variant frequencies for each BBN tumor. Peaks shifting toward the right side of the x-axis indicate accumulation of mutations that are shared by a larger fraction of cancer cells in the tumor (clonal expansion). Line color corresponds to mutation load. Area under the curve (AUC) of each line was set to unity. b Scatterplot showing the relative abundance of MOUSIG-B (top) or COSMIC-22 (bottom) signatures as function of the intra-tumor variant allele frequency. Points in the frequency ranges of 0.225–0.300 (low frequency mutations) and 0.350–0.425 (high frequency mutations) were compared via t-test, and p-values were 1.3e-05 and 1.27e-07, respectively. Trendlines were computed using LOESS (red lines). c Diagram summarizing the hypothesized model that may explain genetic instability in the BBN model. Geometric shapes represent mutations acquired as consequence of processes linked to MOUSIG-A (blue) and MOUSIG-B (red) mutational signatures

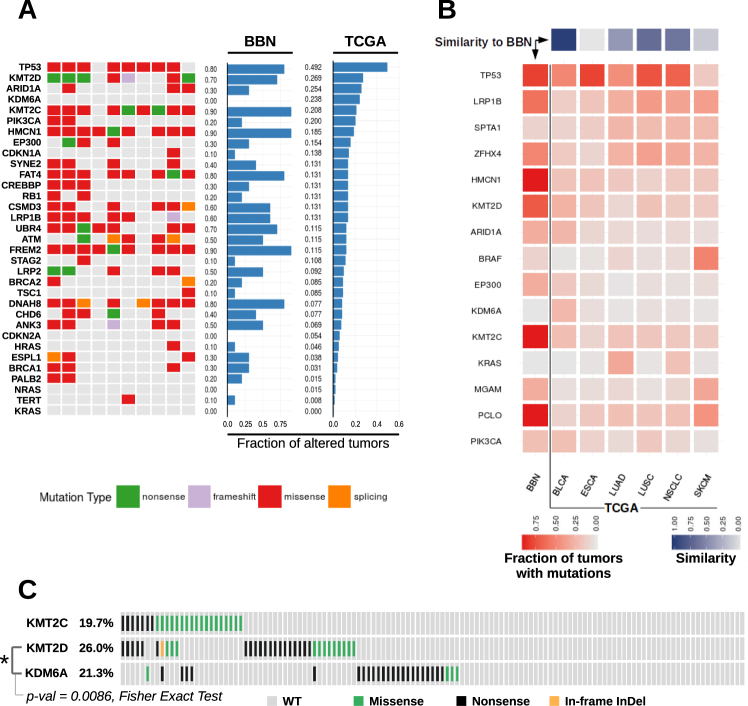

Gene mutations in mouse and human bladder tumors

To understand which genetic aberrations could be responsible of mutational signature switch and clonal expansion in the BBN model, we analyzed the mutation status of bladder cancer-associated genes [10], and compared mouse tumors to bladder cancer genomes from TCGA (Fig. 5a). Similar to TCGA genomes, BBN tumors accumulated mutations in Trp53 (8/10 tumors), Kmt2d (7/10 tumors), Kmt2c (9/10 tumors), and Atm (5/10 tumors). RAS oncogenes (HRAS, KRAS, NRAS) were rarely mutated in human MIBC. Likewise, only one Hras mutation was found in the BBN genomes, suggesting that genes altered in the BBN model tracked with those mutated in human bladder cancer. To further characterize how closely the BBN model aligned to human MIBC, we compared mutation rates across BBN genomes and TCGA cancer datasets. We analyzed tumor types with overall mutation rates comparable to MIBC (supplementary figure S10A), determined a list of 15 genes with the highest overall mutation frequency across these datasets, and computed the fraction of tumors carrying NSVs for each dataset and for each gene (Fig. 5b). A pairwise comparison of gene mutation rates was then performed to determine the similarity of each TCGA dataset with the BBN model. The MIBC dataset was the most similar to the BBN model. Equivalent results were obtained when BBN tumors were compared to other TCGA cancers for which molecular analogies to MIBC were reported (supplementary figure S10B). Altogether, these results showed that the pattern of mutated genes in the BBN model closely replicated human MIBC. Nevertheless, differences between BBN tumors and human MIBC were also identified. Unlike human MIBC, BBN tumors had frequent mutations in genes encoding for epigenetic regulators (supplementary figure S11A). Conversely, the tc-NER gene ERCC2 that is frequently altered in human tumors (12.3%) was never (0/10) mutated in mouse tumors (supplementary figure S11B). Another striking difference implicated the Kdm6a gene, which is frequently mutated in human bladder cancer (~24%) unlike the BBN tumors (0/10). In human MIBC, KMT2D and KDM6A mutations resulted mutually exclusive (Fig. 5c), and the latter was found enriched in low-grade bladder cancer [36]. Therefore, BBN tumors might recapitulate high-grade MIBC with mutations in the KMT2C or KMT2D genes rather than low-grade bladder cancer with KDM6A alterations. Other than being frequently altered in BBN tumors, Trp53, Kmt2c, and Kmt2d specifically accumulated clonal mutations shared among a substantial fraction of cancer cells in each tumor (supplementary figure S12). This observation was suggestive of mutations emerging before cancer cell clonal expansion, and was consistent with a potential driver role of these three genes in the process of BBN-induced tumorigenesis.

Fig. 5.

Bladder cancer gene mutations across BBN and human tumors. a Tile chart displaying cancer gene alterations in 10 BBN tumor genomes (green, nonsense; purple, frameshift; red, missense; orange splicing site; gray, no mutation). Overall gene mutation rates from the BBN dataset and the human TCGA bladder cancer dataset are displayed in the barplots. b TCGA datasets with overall mutation rates comparable to MIBC were analyzed (BLCA bladder cancer, ESCA Esophageal Carcinoma, LUAD lung adenocarcinoma, LUSC Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma, NSCLC Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer, SKCM melanoma). Mutation rates were computed for each tumor type and for each of the 15 genes having the highest overall mutation frequency in the six datasets. Central heatmap displaying mutation rates by gene (rows) across the BBN dataset and TCGA datasets (columns). Square color (red) intensity denotes mutation rate. Top: similarity scores of each TCGA dataset to the BBN dataset were computed as [1— (scaled Canberra distance)] and are displayed via a 1-row heatmap. Square color (purple) intensity denotes the relative similarity to the BBN profile. c Variants occurring in the KMT2C, KMT2D and KDM6A genes in the human bladder cancer TCGA dataset, visualized by oncoprint format. Mutual exclusivity of KMT2D and KDM6A mutations was tested via Fisher Exact Test (p-value = 0.0086)

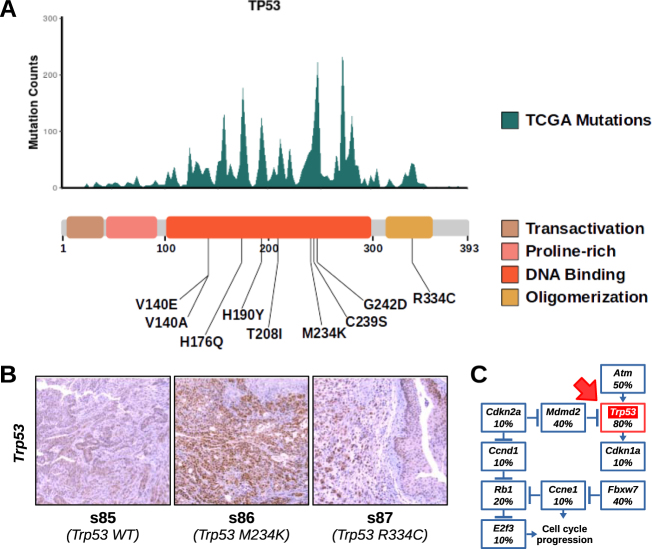

Impact of TP53 mutations in BBN tumors

The tumor suppressor TP53 is one of the most frequently altered genes in both human and BBN-induced tumors. Mutations occurring in the human TP53 gene accumulate at specific positions corresponding to amino acids in the DNA binding and oligomerization domains of the protein. These hotspot TP53 mutations are driver mutations in cancer, since the resulting protein products are deficient in tumor suppression, possess oncogenic properties, and accumulate at high levels in the cells [37]. We aligned the positions of Trp53 mutations from the BBN genomes to hotspots regions retrieved from TCGA provisional datasets. Interestingly, all NSVs in the Trp53 gene from the BBN genomes mapped the DNA binding or the oligomerization domains (Fig. 6a), and coincided with mutational hotspot regions. As expected for human hotspot mutations, immunohistochemistry (IHC) experiments revealed that Trp53 expression levels were higher in tumors carrying mutations (tumors s86 and s87) compared to wild type Trp53 tumors (tumor s85) (Fig. 6b). The M234K mutation matched one of the principal hotspot mutation regions of human TP53 and resulted in the highest Trp53 expression levels. Next, we found that the whole Trp53 pathway was frequently hit in the BBN tumors (Fig. 6c), with recurring mutations in Atm (5/10), Mdm2 (4/10), Fbxw7 (4/10), and Rb1 (2/10). Overall, these evidences supported a key role for Trp53 and its pathway in restricting mouse bladder tumorigenesis.

Fig. 6.

Trp53 mutations in BBN tumors. a Top. Histogram displaying TP53 hotspot mutations from aggregate TCGA genomes (missense, frameshift, and nonsense mutations were included). Bottom. List of variants found in Trp53 mapped to a diagram of the functional domains of the protein. b IHC for Trp53 was performed on tissue sections from normal bladders or BBN tumors expressing wild type (left) or mutant (M234K, center; R334C, right) Trp53. c Diagram displaying the frequency of tumors with mutations in different genes belonging to the Trp53 pathway. Trp53 box is highlighted in red (red arrow)

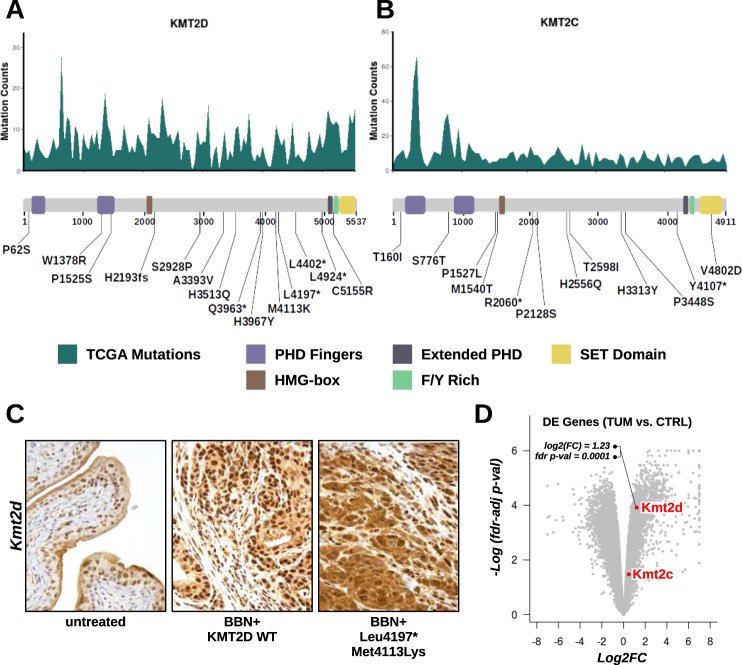

KMT2C and KMT2D mutations in BBN tumors

We also examined whether BBN-induced mutations occurring on Kmt2c and Kmt2d genes clustered at mutational hotspot regions. Unlike TP53, these genes accumulated mutations across their full-length coding sequence (CDS) in human tumors, with less well-defined peaks. Nevertheless, most of the BBN-induced NSVs in Kmt2c and Kmt2d matched local human hotspot peak locations and accumulated in the central part of the CDS, corresponding to the protein region spanning between the HMG-box and the C-terminal SET domain (Fig. 7a, b). IHC experiments revealed that cells in the urothelial layer were those expressing the highest levels of Kmt2d protein in the bladder of untreated animals and that BBN-induced tumors featured a significant Kmt2d over-expression compared to untreated bladders (Fig. 7c). Kmt2d accumulation in BBN tumors was confirmed by RNA-seq (Fig. 7d). It is unclear whether such accumulation was the result of gene expression dysregulation, or the consequence of the enrichment of epithelial-origin cancer cells in the bladder. Notably, selected Kmt2d mutations (Leu4197*, Met4113Lys) disrupted the normal intracellular localization of the protein, forcing the nuclear export of mutated enzyme to the cytoplasm (Fig. 7c), thus confining the methyltransferase away from its DNA substrate.

Fig. 7.

Kmt2c and Kmt2d Mutations in the BBN tumors. (a, b) Top. Histogram displaying Kmt2d (a) or Kmt2c (b) frequently mutated regions calculated from aggregate TCGA genomes (missense, frameshift, and nonsense mutations were included). Bottom. List of variants found in Kmt2d (a) or Kmt2c (b) mapped to a diagram of the functional domains of the proteins. c IHC for Kmt2d was performed on tissue sections from normal bladders (left) or from BBN tumors expressing wild type (center) or mutant (L4197*, M4113K: right) Kmt2d. d Volcano plot showing upregulation of Kmt2d by RNA-seq in BBN tumors compared to control bladders (log2 fold change = 1.23; fdr-adjusted p-value = 0.0001)

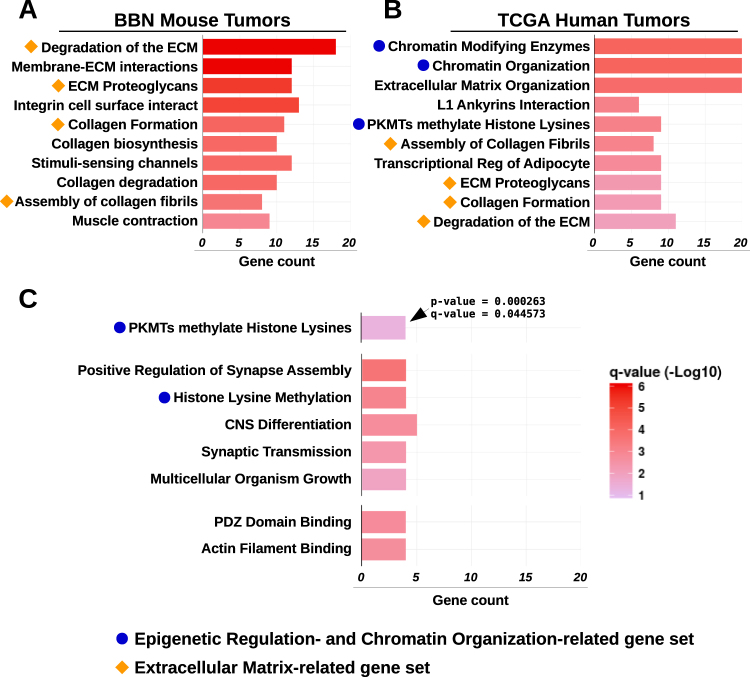

Pathways accumulating high-impact mutations in BBN tumors

We conducted gene set analyses aimed at identifying key pathways associated to the process of bladder tumorigenesis. Genes with mutations in at least five tumors (n = 474) were tested against GO terms, and pathways from the Reactome pathway database [38]. Among the enriched terms we found pathways such as “degradation of the ECM”, and “ECM proteoglycans” (Fig. 8a) and GO terms such as “phosphatase binding” and “protein complex scaffold” (supplementary figure S13A). These and other gene sets were consistently enriched among the most commonly mutated genes in both mouse and human bladder tumors (Fig. 8b). Mutated genes from TCGA human tumors were also enriched in pathways linked to epigenetic regulation, such as “chromatin modifying enzymes”, and “PKMTs methylate histone lysines” (Fig. 8b). Since these terms were missing in our results from the BBN genomes, we reasoned that in the mouse model the extended exposure to the carcinogen might favor the accumulation of passenger mutations that could easily hide high-impact driver mutations. Therefore, we repeated the analysis only including genes (n = 106) with high impact variants (frameshift, nonsense mutations) in at least two BBN tumors (supplementary figure S13B). This revealed the enrichment of terms linked to epigenetic regulation, similar to those identified in human tumors (Fig. 8c). These results showed that both human and mouse bladder tumor mutations hit genes belonging to the same families, and highlighted the importance of chromatin regulators in the biology of the BBN tumors, as well as human MIBC.

Fig. 8.

Pathway enrichment analysis of genes frequently mutated in human and mouse bladder tumors. a Pathway enrichment analysis of commonly mutated genes in BBN tumors against terms from Reactome DB. Orange shapes identify terms related to extracellular matrix. b Pathway enrichment analysis of commonly mutated genes in TCGA tumors against terms from the Reactome DB. Orange shapes identify terms related to extracellular matrix that were identical to those revealed by pathway analysis from BBN genomes. Blue dots indicate terms linked to epigenetic regulation and chromatin organization. c Pathway enrichment analysis of genes accumulating high-impact mutations in BBN tumors against terms from Reactome DB (top), GO molecular function (center) and GO cell component (bottom). Blue dots indicate terms linked to epigenetic regulation and chromatin organization. Bars indicate the number of significant genes (gene count) identified in the list of highly mutated genes and belonging to each GO/ReactomeDB term. Bar color corresponds to −log10(fdr-adjusted p-value). All terms displayed in the charts met statistical significance criteria of q-value < 0.05

Discussion

MIBC is a smoking-related cancer with an unfavorable prognosis and a very limited panel of therapeutic options. Developing novel anticancer therapeutics relies on the availability of model systems that recapitulate the human disease. In our study, we performed a molecular characterization of the BBN mouse model, and compared it to human TCGA bladder cancer to guide its use as MIBC model in cancer research studies.

Our RNA-seq analyses revealed that BBN affected bladder gene expression after as early as 4 weeks of treatment, with activation of immune-related pathways that were only partially detected at later times. This is consistent with an initial recruitment of immune cells in the pre-cancerous bladders, likely as consequence of carcinogen-induced toxicity. Extended BBN exposure could result in a different type of immune response and promote a permissible environment for tumor development [39]. At later times, BBN tumors showed high expression of basal subtype markers, featuring distinct changes in cell cycle-related and metabolism-related pathways.

Our WES analyses showed that, similar to human MIBC, BBN tumors had high mutation burden, with a ~10-fold variation in the DNA mutation rate across samples. We did not detect any correlation between tumor size, tumor histology and mutation load (supplementary figure S14A), suggesting that increasing total number of mutations did not correspond to successive time points in the tumor-progression timeline. Differences in mutation load were likely due to the interaction between carcinogen exposure and tumor-specific status of tumor-suppressor and care-taker genes. Notably, similar observations were derived from human TCGA data, where smoking status, despite being the most important risk factor for bladder cancer [40], was not predictive of mutation load (supplementary figure S14B). In human MIBC, differences in mutation load impacted patient survival [41] and could affect response to drugs, including immune checkpoint inhibitors [42]. Therefore, this provides a biological rationale for using the BBN model in drug discovery studies requiring an immuno-competent context.

Next, we investigated genetic instability processes active in the BBN model. We extracted mutational signatures from the BBN genomes and identified a mutational profile, namely MOUSIG-A, shared by all mouse tumors and very similar to human COSMIC-5 signature. This signature was recently linked to defects of the tc-NER pathway in bladder cancer due to clonal ERCC2 mutations [29]. Interestingly, despite detecting the MOUSIG-A pattern, no ERCC2 mutations were found in the mouse tumors. Even if we cannot rule out the involvement of other defects in DNA repair genes, mutations imputed to COSMIC-5-like signatures may be a direct consequence of exposure to the carcinogen. Since tobacco-specific nitrosamines similar to BBN can generate bulky DNA adducts that are substrates for NER [43], the extended BBN exposure might saturate the DNA repair capabilities of bladder cells, resulting in mutagenesis patterns equivalent to those linked to ERCC2 defects.

Our analyses identified a second mouse mutational signature, namely MOUSIG-B, active in the BBN tumors, and enriched in T>A transversions. These were previously found in MIBC tumors with known exposures to aristolochic acid, a natural occurring carcinogen [44]. On the contrary, no APOBEC Cytidine Deaminase mutational pattern was detected in the BBN tumors. APOBEC is a family of enzymes that promote T[C→T/G]W base substitutions in human cancers including bladder, cervical, breast, and lung cancers [45]. We recently highlighted a correlation between APOBEC3B expression and mutation load in human MIBC, suggesting that the enzyme might contribute to enhance genetic instability [46]. Notably, mice only express one APOBEC3 isoform compared to seven isoforms found in humans. Also, to our knowledge no APOBEC mutational pattern was reported in carcinogen-induced mouse tumor models before. This confirmed that mutational processes active in the BBN tumors are partly similar to human MIBC, but do not replicate the APOBEC mutational pattern.

We examined mutated genes in the BBN tumors and revealed many analogies between human and mouse bladder cancer. Our analyses converged on a list of putative bladder cancer driver genes, including Trp53, Kmt2c, and Kmt2d. By analyzing mutation locations, we found that NSVs hitting these genes in BBN tumors mapped human cancer hotspot mutations. A closer inspection, revealed that hotspot Trp53 mutants were overexpressed in mouse bladder tumors, as previously observed in human cancer cells [37]. Likewise, Kmt2d was upregulated in the tumors and accumulated mutations, some of which affected its functionality by promoting nuclear export. Interestingly, targeted inactivation of the Kmt2c gene was previously found to drive ureter epithelial tumorigenesis in mice [47]. In addition, several reports have suggested a role for Kmt2c and Kmt2d mutations in human cancer [48, 49], including MIBC [36]. The precise mechanism underlying the tumorigenic effect of these mutations is still unclear. Both genes encode for methyltransferases involved in the methylation of histone H3K4 and play a key role in the epigenetic regulation of enhancer activity. Interestingly, functional contacts between Kmt2c and the TP53 pathway were also described [36], suggesting a link with DNA repair pathways. Finally, it was recently shown that mutated Kmt2d proteins might include highly immunogenic neoantigen peptides [49], supporting the idea that Kmt2c and Kmt2d may play two concomitant roles in both human and mouse cancer as drivers of tumorigenesis as well as potential targets in cancer therapeutics.

Notably, we did not observe any mutation in Kdm6a, a gene often (24%) hit in human MIBC. In TCGA tumors, KDM6A mutations were mutually exclusive with KMT2D. Since Kmt2d or Kmt2c were mutated in most of the BBN tumors, loss Kdm6a may not be required for oncogenesis. Additionally, KDM6A mutations were found enriched in low-grade low-stage luminal bladder tumors [36], suggesting that the BBN model might be a good model for high-grade basal-like MIBC. Also, Kdm6a gene is located on the X chromosome in both human and mouse genomes, therefore the lack of Kdm6a mutations in BBN tumors may be due at least in part to its hemizygous state in male mice.

Together, our study highlights several aspects of close proximity as well as some important differences between human high-grade MIBC and the BBN model, and supports the use of such model in studies of bladder cancer progression and drug discovery.

Materials and methods

Bladder cancer models

Mice were cared for in a fashion supervised by the ACUC at Northwestern University and all research was approved in an animal research protocol. Male C57/B6 mice at least 6 weeks old received BBN at a dose of 0.05% in drinking water ad libitum. After 4 or 20 weeks of exposure, mice were euthanized by CO2 with secondary cervical dislocation. Bladders were removed and divided in the sagittal plane, and either fixed in 10% formalin or snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. MBT2 and MB49 cells were obtained from Dr. Timothy Ratliff (Purdue University).

RNA and DNA extraction, library creation and next generation sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from homogenized bladders (n = 14) using RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) and then depleted of rRNA by use of Ribo-zero (Illumina, San Diego, CA), and libraries were made with a Tru-Seq mRNA kit (Illumina). Genomic DNA was extracted from mouse bladders (n = 12) using the DNeasy Blood and tissue kit (Qiagen) according to the recommended instructions. WES library preparation and sequencing was performed at the Epigenomics Core at Weill Cornell Medical College. Libraries were prepared using the SureSelect XT Target Enrichment kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Agencourt AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, Indianapolis, IN) and Dynabeads MyOne Streptavidin magnetic beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) were used for the cleaning steps. For both RNA-seq and WES, libraries were quantified using a Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY), quality-checked by DNA1000 Bioanalyzer chip (Agilent Technologies), and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 (Illumina).

Bioinformatics and statistical analysis

TopHat [50] (ver-2.0.10) was used to align RNA-seq reads. Cuffdiff [51] (ver-1.3.0) and the R package edgeR [52] (ver-3.0.8) were used to analyze differentially expressed genes. WES reads were mapped to mouse reference genome (mm10) with Burrows–Wheeler aligner [53] (ver-0.7.12-r1039). Aligned reads were further processed using Picard (ver-1.85). Variants were detected using samtools and bcftools [54] (ver-1.2), and then annotated using SnpEff [55] (ver-4.1). Germline polymorphisms from the dbSNP build146 were removed. Copy number alterations were estimated based on the WES outputs using Control-FREEC [22]. Pathway enrichment analyses were performed using topGO [56] (ver-2.24.0.) or ReactomePA [57] against a universe gene list from mm10 Ensembl release-75.

Mutational profiles and signature analysis

Tri-nucleotide context was retrieved for each variant using org.Mm.eg.db (ver-3.3.0). Mutational signatures were deciphered using the WTSI Mutational Signature Framework [28] or mutSignatures, an in-house R-ported version the same framework. The contribution of mutational signatures to mutation catalogs detected in mouse or human genomes was determined using NMF [58] or DeconstructSigs [59], with overlapping results. The TCGA bladder cancer mutational catalog for supplementary figure S6 was obtained from Alexandrov et al. [28].

TCGA data analysis and comparisons with BBN tumor mutations

In-house R scripts were developed to download TCGA mutation data from cBioPortal [60] and detect gene mutations, mutation hotspots as well as similarities between patterns of mutations (TCGAretriever R package). Similarity scores between TCGA datasets and BBN tumors were obtained by calculating the Canberra distance between mutation rates across cancer datasets and using the proxy package. Oncoprints were plotted using ggplot2. Mutual exclusivity was assessed by a Fisher Exact (one-tailed) test.

Sequenza pipeline and analysis of intra-tumor variant allele frequencies distribution

Cellularity, ploidy and intra-tumor variant allele frequencies were determined using Sequenza [33] and an in-house modified version of copynumber [61] that allowed segmentation of the mm10 genome. Adjusted intra-tumor variant allele frequencies were computed by dividing variant allele frequencies by the corresponding tumor cellularity. Kernel density estimates were computed using the density function from the R stats package. To examine the link between variant allele frequency and signature or mutation types, mutations were iteratively subset based on an incremental threshold in the range 0.225–0.525 or a sliding range. Next, relative rates of T>A transversions, signature MOUSIG-B, or COSMIC-22 for each tumor were computed. At each iteration, the median relative rate was returned. Normalized median rates were plotted as a function of variant frequency thresholds.

Immunohistochemistry

Bladders were fixed in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin. Antibodies against TP53 (1:250, Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX), KMT2D (1:500, created in A. Shilatifard laboratory), and anti-rabbit EnVision+System-HRP (Dako, Santa Clara, CA) were used for IHC. KMT2D antibody specificity was assessed using KMT2D wild type and homozygote-mutant cell lines. No expression of KMT2D was detected in KMT2D-mutant cells.

Code availability

R code use for accessing TCGA data from the cbioportal server (‘TCGAretriever’ package) and for analyzing and extracting mutational signatures (‘mutSignatures’ package) is available at The Comprehensive R Archive Network (https://cran.r-project.org/).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Francesco Favero (Technical University of Denmark) for assistance with the use of the sequenza and copynumber R libraries, Dr. Vania Vidimar (Northwestern University) for insightful discussions and editorial assistance in writing the manuscript, and Dr. Andrea Piunti (Northwestern University) for help with RNA extraction and RNA-seq library preparation. JJM is supported by grant BX003692 and the John P. Hanson Foundation for Cancer Research at the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University, JDL is supported by R01 CA180475, DT is supported by CA075115. CKC, EB and AS are supported by R35CA197569 awarded to AS.

Author contributions

DF, JJM, AY, YY, JDL, CKC, AS, DT, EB designed research experiments. DF, JJM, NV, MS, YY, AY, CKC, AS, JDL, AB, AR, SEC analyzed data. DF developed R extensions, performed downstream data analyses and data visualization. DF, JJM, APG, KJR, YW, MS, NV, AR, AB, AY, YY, SEC, DH, JDL, CKC, EB, DT, AS wrote and reviewed the manuscript. DF, JJM, MS, NV, AB, AY, YY, DH, YW, CCS, LW, ZZ performed research.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41388-017-0099-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horstmann M, Witthuhn R, Falk M, Stenzl A. Gender-specific differences in bladder cancer: a retrospective analysis. Gend Med. 2008;5:385–94. doi: 10.1016/j.genm.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Y, Zhu C, Curado MP, Zheng T, Boyle P. Changing patterns of bladder cancer in the USA: evidence of heterogeneous disease. BJU Int. 2012;109:52–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10283.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stein JP, Lieskovsky G, Cote R, Groshen S, Feng AC, Boyd S, et al. Radical cystectomy in the treatment of invasive bladder cancer: long-term results in 1,054 patients. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:666–75. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.3.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenberg JE, Hoffman-Censits J, Powles T, van der Heijden MS, Balar AV, Necchi A, et al. Atezolizumab in patients with locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma who have progressed following treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy: a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2016;387:1909–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00561-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma P, Callahan MK, Bono P, Kim J, Spiliopoulou P, Calvo E, et al. Nivolumab monotherapy in recurrent metastatic urothelial carcinoma (CheckMate 032): a multicentre, open-label, two-stage, multi-arm, phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1590–8. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30496-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kobayashi T, Owczarek TB, McKiernan JM, Abate-Shen C. Modelling bladder cancer in mice: opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15:42–54. doi: 10.1038/nrc3858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Comprehensive molecular characterization of urothelial bladder carcinoma. Nature. 2014;507:315–22. doi: 10.1038/nature12965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi W, Porten S, Kim S, Willis D, Plimack ER, Hoffman-Censits J, et al. Identification of distinct basal and luminal subtypes of muscle-invasive bladder cancer with different sensitivities to frontline chemotherapy. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:152–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nickerson ML, Witte N, Im KM, Turan S, Owens C, Misner K, et al. Molecular analysis of urothelial cancer cell lines for modeling tumor biology and drug response. Oncogene. 2017;36:35–46. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Varley KE, Gertz J, Bowling KM, Parker SL, Reddy TE, Pauli-Behn F, et al. Dynamic DNA methylation across diverse human cell lines and tissues. Genome Res. 2013;23:555–67. doi: 10.1101/gr.147942.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ding L, Ellis MJ, Li S, Larson DE, Chen K, Wallis JW, et al. Genome remodelling in a basal-like breast cancer metastasis and xenograft. Nature. 2010;464:999–1005. doi: 10.1038/nature08989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goodspeed A, Heiser LM, Gray JW, Costello JC. Tumor-derived cell lines as molecular models of cancer pharmacogenomics. Mol Cancer Res. 2016;14:3–13. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-15-0189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Puzio-Kuter AM, Castillo-Martin M, Kinkade CW, Wang X, Shen TH, Matos T, et al. Inactivation of p53 and Pten promotes invasive bladder cancer. Genes Dev. 2009;23:675–80. doi: 10.1101/gad.1772909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagao M, Suzuki E, Yasuo K, Yahagi T, Seino Y. Mutagenicity of N-butyl-N-(4-hydroxybutyl)nitrosamine, a bladder carcinogen, and related compounds. Cancer Res. 1977;37:399–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vasconcelos-Nobrega C, Colaco A, Lopes C, Oliveira PA. Review: BBN as an urothelial carcinogen. Vivo. 2012;26:727–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shin K, Lim A, Odegaard JI, Honeycutt JD, Kawano S, Hsieh MH, et al. Cellular origin of bladder neoplasia and tissue dynamics of its progression to invasive carcinoma. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:469–78. doi: 10.1038/ncb2956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Batavia J, Yamany T, Molotkov A, Dan H, Mansukhani M, Batourina E, et al. Bladder cancers arise from distinct urothelial sub-populations. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:982–91. doi: 10.1038/ncb3038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liang Y, Zhu F, Zhang H, Chen D, Zhang X, Gao Q, et al. Conditional ablation of TGF-beta signaling inhibits tumor progression and invasion in an induced mouse bladder cancer model. Sci Rep. 2016;6:29479. doi: 10.1038/srep29479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dadhania V, Zhang M, Zhang L, Bondaruk J, Majewski T, Siefker-Radtke A, et al. Meta-analysis of the luminal and basal subtypes of bladder cancer and the identification of signature immunohistochemical markers for clinical use. EBioMedicine. 2016;12:105–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yao R, Lemon WJ, Wang Y, Grubbs CJ, Lubet RA, You M. Altered gene expression profile in mouse bladder cancers induced by hydroxybutyl(butyl)nitrosamine. Neoplasia. 2004;6:569–77. doi: 10.1593/neo.04223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boeva V, Popova T, Bleakley K, Chiche P, Cappo J, Schleiermacher G, et al. Control-FREEC: a tool for assessing copy number and allelic content using next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:423–5. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Allen EM, Mouw KW, Kim P, Iyer G, Wagle N, Al-Ahmadie H, et al. Somatic ERCC2 mutations correlate with cisplatin sensitivity in muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2014;4:1140–53. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moriya M, Slade N, Brdar B, Medverec Z, Tomic K, Jelakovic B, et al. TP53 Mutational signature for aristolochic acid: an environmental carcinogen. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:1532–6. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sidorenko VS, Yeo JE, Bonala RR, Johnson F, Scharer OD, Grollman AP. Lack of recognition by global-genome nucleotide excision repair accounts for the high mutagenicity and persistence of aristolactam-DNA adducts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:2494–505. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo G, Sun X, Chen C, Wu S, Huang P, Li Z, et al. Whole-genome and whole-exome sequencing of bladder cancer identifies frequent alterations in genes involved in sister chromatid cohesion and segregation. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1459–63. doi: 10.1038/ng.2798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Summerhayes IC, Franks LM. Effects of donor age on neoplastic transformation of adult mouse bladder epithelium in vitro. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1979;62:1017–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC, Aparicio SA, Behjati S, Biankin AV, et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature. 2013;500:415–21. doi: 10.1038/nature12477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim J, Mouw KW, Polak P, Braunstein LZ, Kamburov A, Kwiatkowski DJ, et al. Somatic ERCC2 mutations are associated with a distinct genomic signature in urothelial tumors. Nat Genet. 2016;48:600–6. doi: 10.1038/ng.3557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen CH, Dickman KG, Moriya M, Zavadil J, Sidorenko VS, Edwards KL, et al. Aristolochic acid-associated urothelial cancer in Taiwan. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:8241–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119920109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burrell RA, McGranahan N, Bartek J, Swanton C. The causes and consequences of genetic heterogeneity in cancer evolution. Nature. 2013;501:338–45. doi: 10.1038/nature12625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bozic I, Antal T, Ohtsuki H, Carter H, Kim D, Chen S, et al. Accumulation of driver and passenger mutations during tumor progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:18545–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010978107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Favero F, Joshi T, Marquard AM, Birkbak NJ, Krzystanek M, Li Q, et al. Sequenza: allele-specific copy number and mutation profiles from tumor sequencing data. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:64–70. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Calderwood SK. Tumor heterogeneity, clonal evolution, and therapy resistance: an opportunity for multitargeting therapy. Discov Med. 2013;15:188–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greaves M, Maley CC. Clonal evolution in cancer. Nature. 2012;481:306–13. doi: 10.1038/nature10762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gui Y, Guo G, Huang Y, Hu X, Tang A, Gao S, et al. Frequent mutations of chromatin remodeling genes in transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Nat Genet. 2011;43:875–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pfister NT, Prives C. Transcriptional regulation by wild-type and cancer-related mutant forms of p53. Cold Spring HarbPerspect Med. 2017;7:1–26. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a026054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Croft D, Mundo AF, Haw R, Milacic M, Weiser J, Wu G, et al. The Reactome pathway knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D472–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140:883–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zeegers MP, Tan FE, Dorant E, van Den, Brandt PA. The impact of characteristics of cigarette smoking on urinary tract cancer risk: a meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. Cancer. 2000;89:630–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000801)89:3<630::AID-CNCR19>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kardos J, Chai S, Mose LE, Selitsky SR, Krishnan B, Saito R, et al. Claudin-low bladder tumors are immune infiltrated and actively immune suppressed. JCI Insight. 2016;1:e85902. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.85902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Topalian SL, Taube JM, Anders RA, Pardoll DM. Mechanism-driven biomarkers to guide immune checkpoint blockade in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:275–87. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peterson LA. Formation, repair, and genotoxic properties of bulky DNA adducts formed from tobacco-specific nitrosamines. J Nucleic Acids. 2010;2010:1–11. doi: 10.4061/2010/284935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Poon SL, Huang MN, Choo Y, McPherson JR, Yu W, Heng HL, et al. Mutation signatures implicate aristolochic acid in bladder cancer development. Genome Med. 2015;7:38. doi: 10.1186/s13073-015-0161-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roberts SA, Lawrence MS, Klimczak LJ, Grimm SA, Fargo D, Stojanov P, et al. An APOBEC cytidine deaminase mutagenesis pattern is widespread in human cancers. Nat Genet. 2013;45:970–6. doi: 10.1038/ng.2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Glaser AP, Fantini D, Shilatifard A, Schaeffer EM, Meeks JJ. The evolving genomic landscape of urothelial carcinoma. Nat Rev Urol. 2017;14:215–29. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2017.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee J, Kim DH, Lee S, Yang QH, Lee DK, Lee SK, et al. A tumor suppressive coactivator complex of p53 containing ASC-2 and histone H3-lysine-4 methyltransferase MLL3 or its paralogue MLL4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:8513–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902873106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sze CC, Shilatifard A. MLL3/MLL4/COMPASS family on epigenetic regulation of enhancer function and cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2016;6:a026427. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a026427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li X. Emerging role of mutations in epigenetic regulators including MLL2 derived from The Cancer Genome Atlas for cervical cancer. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:252. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3257-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Trapnell C, Pachter L, Salzberg SL. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1105–11. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, van Baren MJ, et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:511–5. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:139–40. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–60. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cingolani P, Platts A, Wang le L, Coon M, Nguyen T, Wang L, et al. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strainw1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly (Austin) 2012;6:80–92. doi: 10.4161/fly.19695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kramer F, Beissbarth T. Working with ontologies. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1525:123–35. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6622-6_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yu G, He QY. ReactomePA: an R/Bioconductor package for reactome pathway analysis and visualization. Mol Biosyst. 2016;12:477–9. doi: 10.1039/C5MB00663E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gaujoux R, Seoighe C. A flexible R package for nonnegative matrix factorization. BMC Bioinforma. 2010;11:367. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rosenthal R, McGranahan N, Herrero J, Taylor BS, Swanton C. DeconstructSigs: delineating mutational processes in single tumors distinguishes DNA repair deficiencies and patterns of carcinoma evolution. Genome Biol. 2016;17:31. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-0893-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G, Gross B, Sumer SO, et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal. 2013;6:pl1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nilsen G, Liestol K, Van Loo P, Moen Vollan HK, Eide MB, Rueda OM, et al. Copynumber: Efficient algorithms for single- and multi-track copy number segmentation. BMC Genom. 2012;13:591. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.