Abstract

Arabidopsis thaliana could have easily escaped human scrutiny. Instead, Arabidopsis has become the most widely studied plant in modern biology despite its absence from the dinner table. Pairing diminutive stature and genome with prodigious resources and tools, Arabidopsis offers a window into the molecular, cellular, and developmental mechanisms underlying life as a multicellular photoautotroph. Many basic discoveries made using this plant have spawned new research areas, even beyond the verdant fields of plant biology. With a suite of resources and tools unmatched among plants and rivaling other model systems, Arabidopsis research continues to offer novel insights and deepen our understanding of fundamental biological processes.

Keywords: model organism, reference plant

HUMANS have experimented with plants since the dawn of agriculture. The logic of modern science, the invention of analytical technology, and the adoption of Arabidopsis thaliana as a model organism have created an explosion in our understanding of plant structure and function. Arabidopsis research has helped form the foundation of modern biology.

Historically, human interactions with plants were often focused on crop yields. Many modern crops have been subjected to millennia of artificial selection and only bear passing resemblance to their wild relatives (Doebley et al. 1995; Tanksley and Mccouch 1997). Selection for greater yield and seedlessness has, in many cases, involved polyploidy (Özkan et al. 2002; Rapp et al. 2010; Perrier et al. 2011), which complicates genetic research. In contrast, the Arabidopsis varieties commonly used in laboratories are recently descended from wild plants (Mitchell-Olds 2001) and remain diploid.

Beyond their essential underpinning of human nutrition, plants offer many advantages as research organisms. Compared to most organisms, the metabolic complexity of plants is staggering, offering fertile ground for biochemical research. Plant development is plastic and modular, tolerating many experimental insults. Perhaps the most convenient trait among seed plants is dormancy—seeds can be easily stored and shared. Among plants, Arabidopsis is small, grows quickly, and flourishes indoors (Figure 1). A wealth of Arabidopsis tools, resources, and shared experiences facilitate efficient generation of data and new understanding.

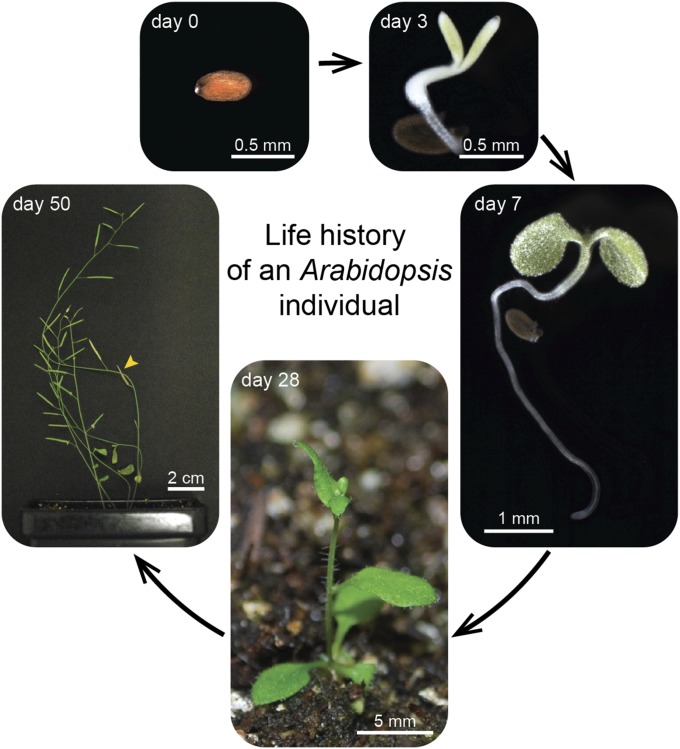

Figure 1.

Life history of an Arabidopsis plant. The seed was photographed prior to surface sterilization and placement on plant nutrient medium (Haughn and Somerville 1986) solidified with 0.6% (w/v) agar. The plate was sealed against contaminants using surgical tape and incubated vertically at 22° under continuous light. The radicle (embryonic root) had emerged from the testa (seed coat) by 3 days. Green cotyledons (embryonic leaves), emerging true leaves, an expanded hypocotyl (embryonic stem), and an elongated root were apparent by 7 days. After 13 days, the seedling was transferred to soil and grown at room temperature under continuous fluorescent light, then photographed shortly after the transition to flowering (28 days) and after dry seed pods (siliques; arrowhead) containing mature seeds were apparent (50 days).

Arabidopsis History

The ancestors of A. thaliana diverged to become a distinct Arabidopsis clade ∼6 MYA (Hohmann et al. 2015). Early descriptions of the plant used aliases. The plant is native to Europe and Asia (Hoffmann 2002), and at the same time that Elizabeth I ruled England and Tycho Brahe was documenting the comet of 1577, the physician Johannes Thal was finishing a book describing the plants of the Harz Mountains in what is now Central Germany. Thal’s descriptions included a plant he named Pilosella siliquata (Thal 1588). Linnaeus renamed the plant, placing it in the genus Arabis and assigning a species name in honor of Thal, hence Arabis thaliana (Linnaeus 1753). The plant was later called by the varied appellations Pilosella thaliana, Conringia thaliana, and Sisymbrium thalianum (Holl and Heynhold 1842; Rydberg 1907). When the Arabis-like genus Arabidopsis was created, the species thaliana was initially retained in Arabis (De Candolle 1824). Only later was thaliana migrated into the genus Arabidopsis (Holl and Heynhold 1842). After continuing controversy about the placement of the species into the Arabidopsis genus, the Berlin code cemented the name by establishing Arabidopsis thaliana as the type for the genus (Greuter et al. 1988).

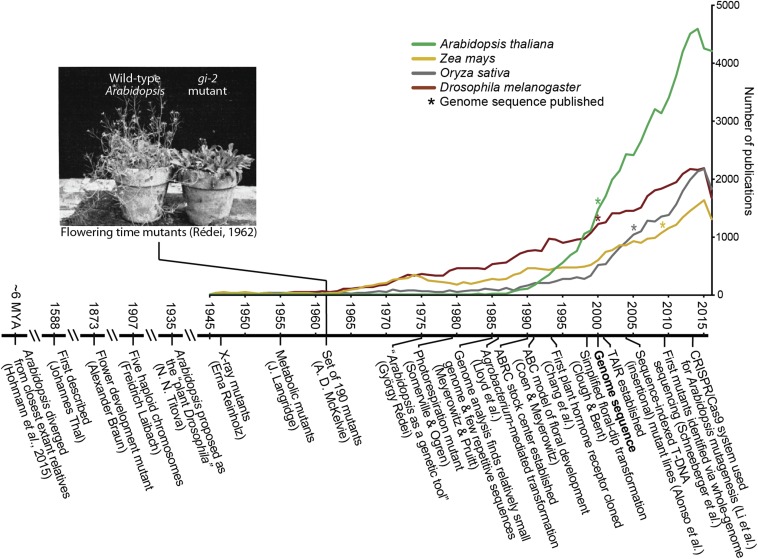

Early observers did not esteem Arabidopsis. In Flora Londinensis, William Curtis remarked that “we have it frequent enough on our walls, and sometimes on dry ground, about town: and it may be found in great abundance on the south side of Greenwich Park Wall… No particular virtues or uses are ascribed to it” (Curtis 1777). To modern science, Arabidopsis is a most useful plant. The number of Arabidopsis publications over the last decade has exceeded those of model plants that double as crops like maize and rice, as well as the classic genetic model organism Drosophila melanogaster (Figure 2); over 50,000 Arabidopsis articles had been published by 2015 (Provart et al. 2016). Many of these are cited in articles focused on other organisms, highlighting the fundamental importance of Arabidopsis research to biology.

Figure 2.

Arabidopsis publications and selected milestones. The graph plots the number of publications since 1945 featuring selected model organisms gathered from PubMed (NCBI Resource Coordinators 2017) searches using full genus and species names as search terms. Asterisks indicate the date when the genome sequence was first published for each model. The photograph of wild type and a late-flowering mutant is adapted from an early Arabidopsis paper in Genetics (Rédei 1962). The timeline highlights selected events in Arabidopsis history (Thal 1588; Braun 1873; Laibach 1907; Titova 1935; Reinholz 1947; Langridge 1955; McKelvie 1962; Rédei 1975; Somerville and Ogren 1979; Meyerowitz and Pruitt 1985; Lloyd et al. 1986; Coen and Meyerowitz 1991; Chang et al. 1993; Clough and Bent 1998; Alonso et al. 2003; Schneeberger et al. 2009; Li et al. 2013; Hohmann et al. 2015).

The Utility of Arabidopsis as a Model Organism

Arabidopsis research is fast, cheap, and convenient. Arabidopsis plants can develop from a seed to a plant bearing mature seeds in as few as 6 weeks, depending on growth conditions (Figure 1). They can grow indoors under feeble fluorescent lighting that is easy to achieve in the laboratory but inadequate for many plants. Seeds and seedlings are small enough to germinate by the hundreds on a single Petri dish. No coculture of any other species is required for Arabidopsis to flourish, allowing aseptic growth conditions and maximal control of variables.

Beyond speed and size, several additional features make Arabidopsis amenable to genetic research. The genome is small (∼132 Mbp) for a plant, with ∼38,000 loci, including >20,000 protein-coding genes dispersed among five nuclear chromosomes (Arabidopsis Genome Initiative 2000; Cheng et al. 2017). Unlike many genetic models (and many other plants), Arabidopsis can tolerate a high degree of homozygosity and is self-fertile; each individual can produce tens of thousands of offspring.

Whereas animals eat, autotrophic plants weave themselves from thin air by capturing carbon dioxide and solar energy. Animal defenses are tooth and claw, horn and hoof. Plants prefer poisons. Arabidopsis chemically deters herbivores in part by producing pungent glucosinolates (Hogge et al. 1988). Both autotrophy and chemical defenses contribute to the tremendous chemical and enzymatic diversity in Arabidopsis that is fertile ground for study.

Unlike most microbial autotrophs, plants are multicellular. The added dimension of differentiation offers exciting research avenues. Arabidopsis models most typical features and specialized cell types of seed plants, including perfect flowers (“perfect” referring to the presence of both stamens and carpel; Figure 3), stems, apical meristems, simple leaves, trichomes (defensive leaf hairs; Figure 4), epidermal pavement cells that interlock to form an outer barrier (Figure 5), stomata that open or close to regulate gas exchange between the leaf and atmosphere (Figure 5), roots, root hairs, vascular tissue, pollen (Figure 6), and female gametophytes. Furthermore, as a winter annual, Arabidopsis undergoes biphasic development. It first produces a compact set of rosette leaves. Then, given appropriate environmental and genetic factors, the plant develops inflorescences that bear self-fertile flowers and, later, siliques (seed pods) (Figure 1). Arabidopsis survival and development are influenced by many environmental signals, including temperature, photoperiod, and the presence (Figure 7), wavelength, and intensity of light.

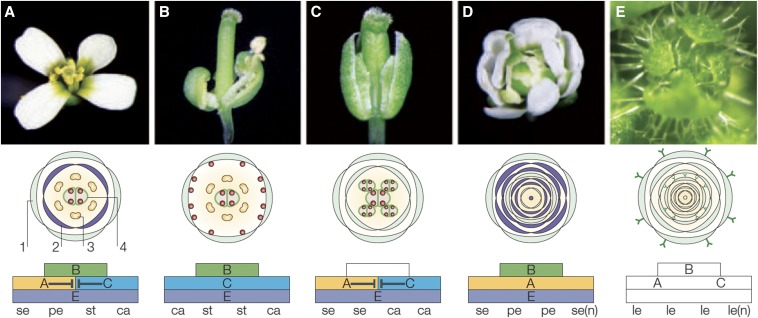

Figure 3.

The ABCE model of floral development is supported by Arabidopsis research. Wild-type Arabidopsis flowers consist of four floral whorls: 1 - sepals (se), 2 - petals (pe), 3 - stamens (st), and 4 - carpels (ca), shown in panel A. Sepals result from the combined activity of A and E genes; petals from B, A, and E genes, stamens from B, C, and E genes, and carpels from C and E genes. A and C genes are mutually repressive. To the right of wild type, four cases of disrupted floral development are shown. (B) In the absence of A-gene activity, only carpels and stamens form. (C) In the absence of B-gene activity, only sepals and carpels form. (D) In the absence of C-gene activity, only numerous sepal and petal structures form. (E) In the absence of E-gene activity, no floral structures form, and the numerous whorls resemble leaves (le), including the presence of leaf hairs (trichomes) decorating the surfaces. Figure modified from Krizek and Fletcher (2005).

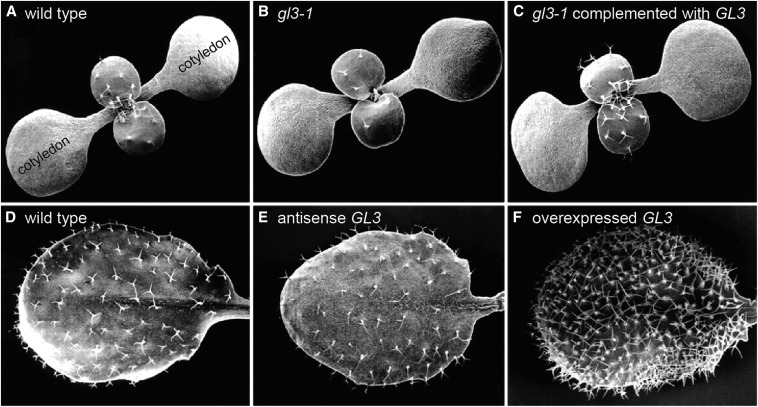

Figure 4.

Leaf epidermal development: A gene regulating Arabidopsis trichome density. Scanning electron micrographs of (A) wild-type seedlings or (D) leaves show trichomes (leaf hairs) distributed on the top surface of true leaves (A and D) but not cotyledons (A). Reducing function of the GL3 transcription factor by (B) mutation or by (E) expressing a GL3 antisense construct results in fewer epidermal cells entering the trichome lineage. Introducing a wild-type copy of the gene restores trichome formation on true leaves in gl3-1 (C), and overexpressing GL3 in wild type results in excessive trichome formation (F). Figure modified from Payne et al. (2000).

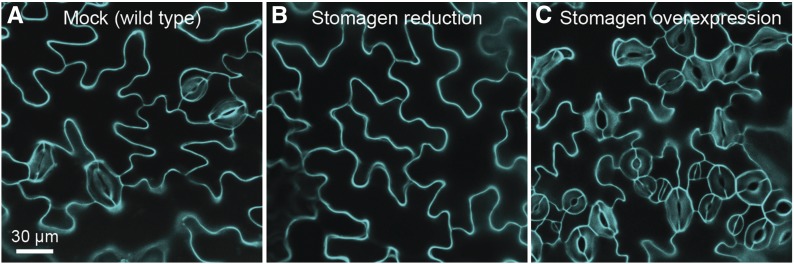

Figure 5.

Tissue-level research: A secreted peptide controlling differentiation of Arabidopsis stomata. Confocal micrographs show the top surface of cotyledons from 10-day-old seedlings stained with propidium iodide to outline epidermal cells. (A) Stomata, the two-celled pores that regulate gas exchange, are distributed among interlocked pavement cells in wild type. Decreasing (B) or increasing (C) levels of the stomagen peptide eliminates or increases, respectively, formation of stomata (Lee et al. 2015). Images provided by Jin Suk Lee and Keiko Torii.

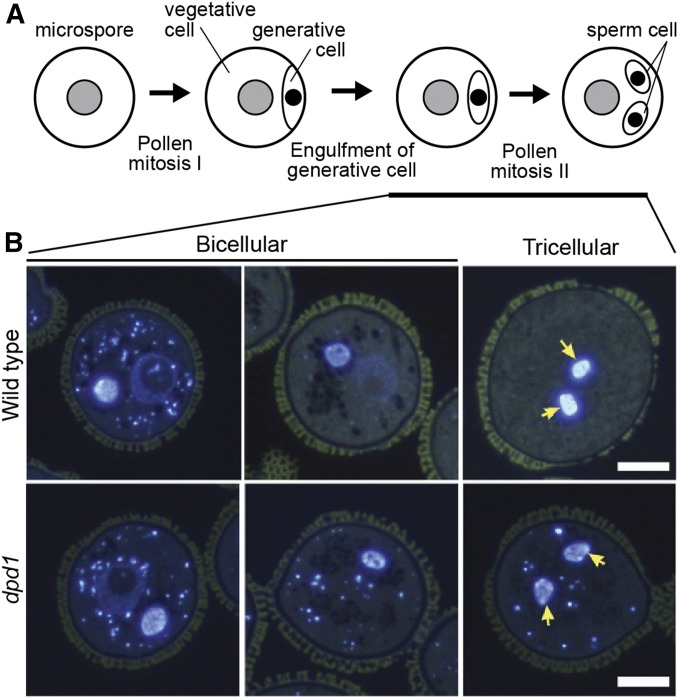

Figure 6.

Subcellular research in Arabidopsis: Pollen organellar DNA degradation. (A) Microspore cells develop into pollen by two rounds of mitosis, producing two sperm cells within a generative cell. (B) shows microscopic sections at different developmental stages with DNA stained blue using DAPI. In wild type, organellar DNA in the vegetative cell is degraded. The dpd1 mutant, defective in an exonuclease, has persistent organellar DNA (plastidial and mitochondrial) through the tricellular stage of development. Yellow arrows indicate nuclear DNA visible in the selected section at the tricellular stage of development. Figure modified from Matsushima et al. (2011) with permission from the American Society of Plant Physiologists.

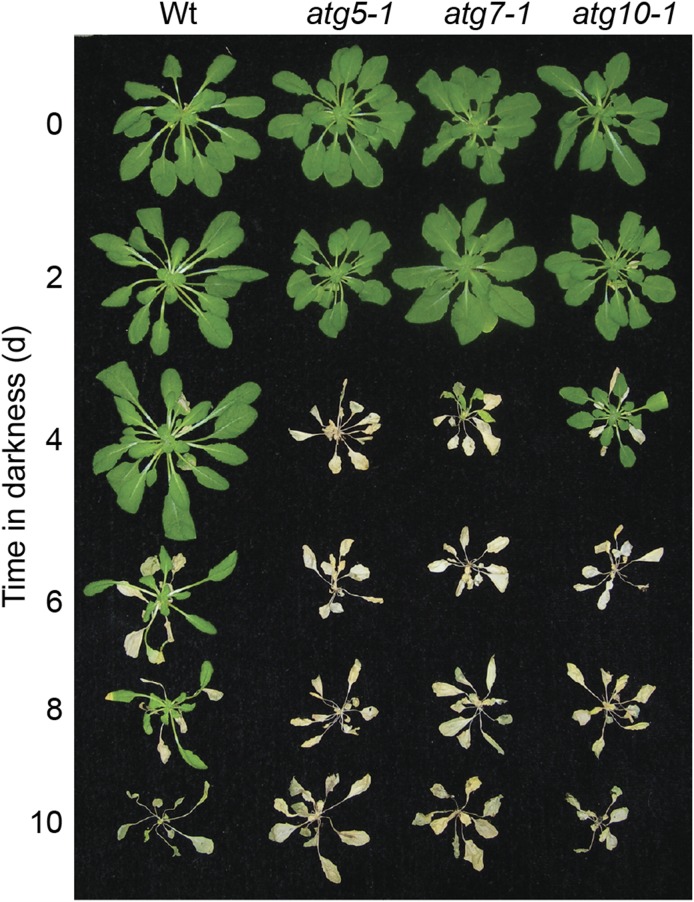

Figure 7.

Arabidopsis at the intersection of genes and environment: Sensitivity to extended darkness in autophagy mutants. Reverse-genetics mutants carrying T-DNA insertions in genes essential for autophagy (atg mutants) fail to recover from the return to light after extended darkness. Figure modified from Phillips et al. (2008).

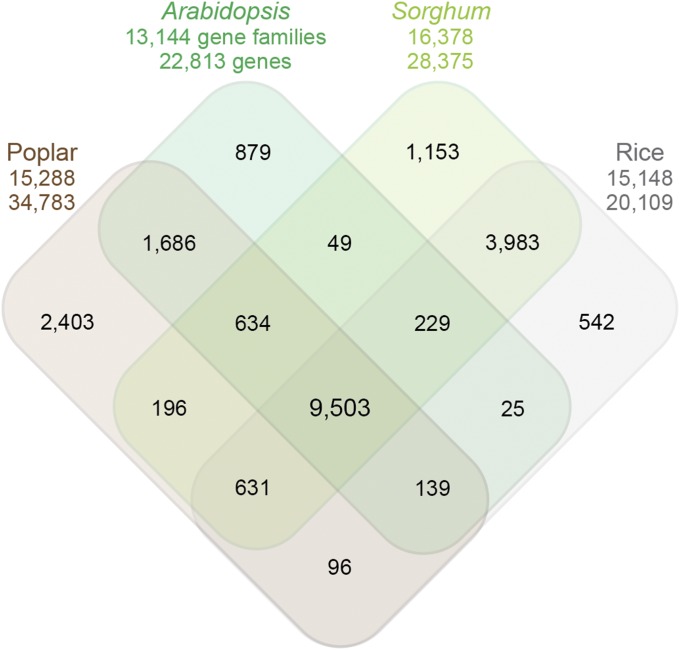

Arabidopsis research has revealed the inner workings of other plants. About three out of four gene families present in Arabidopsis are present in other flowering plants (Figure 8). Therefore, gene functions discovered in Arabidopsis are often similar in other plants (Figure 9). For example, hormones often function similarly across plant species, and the receptors and signaling pathways of almost all plant hormones have been elucidated in Arabidopsis (Provart et al. 2016).

Figure 8.

Comparative genomics of Arabidopsis thaliana, Populus trichocarpa (poplar) trees, and the grain crops Sorghum bicolor and Oryza sativa (rice). The number of genes and gene families for each species is shown. The Venn diagram shows the number of unique and shared gene families. Arabidopsis and Populus are dicotyledonous plants; Sorghum and rice are monocots. Approximately two-thirds of Arabidopsis gene families (9503) are shared among all of these plant species. Figure modified from Paterson et al. (2009) with permission from Springer Nature.

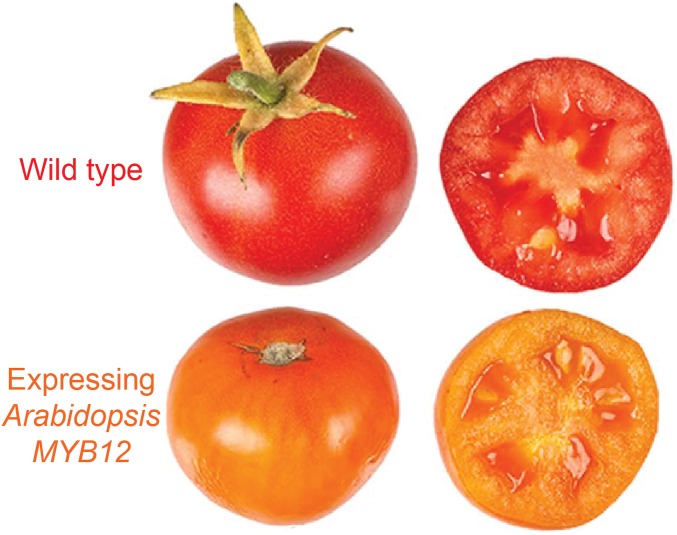

Figure 9.

Translational research: Arabidopsis MYB12 increases tomato flavonol content. Wild-type tomatoes of the Micro-Tom variety are red (top). When an Arabidopsis gene that increases phenolic content is introduced into tomato, the increase in yellow flavonols in the presence of the typical red lycopene results in an orange appearance (bottom). Thus, the gene has a similar impact on this crop plant as was first demonstrated in Arabidopsis. Image modified from Zhang et al. (2015).

The Arabidopsis Toolkit

Most tools available in nonplant model systems are available in Arabidopsis. Forward-genetic screens are routinely initiated by mutagenizing seeds with ethyl methanesulfonate (Koornneef and Van Der Veen 1980), irradiation (Reinholz 1947), fast-neutron bombardment (Timofeev-Resovskii et al. 1971), or sodium azide (Blackwell et al. 1988). The M2 progeny of these self-pollinated M1 plants are then screened for phenotypes of interest, allowing isolation of homozygous recessive mutations. Targeted mutagenesis is also possible, most recently using the CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing system (Li et al. 2013). Arabidopsis can be transformed using a facile dip of plants that have begun to flower into Agrobacterium tumefaciens culture (Clough and Bent 1998). The transferred DNA (T-DNA) that is inserted into the plant genome by Agrobacterium as part of the natural lifestyle of the microbe (Yajko and Hegeman 1971) has been modified to include genes or reporters of interest or can be exploited as an insertional mutagen (Alonso et al. 2003), allowing for reverse-genetics research (e.g., Figure 7).

Beyond the Arabidopsis techniques available to individual research groups, there are useful curated community collections. Mutants can be obtained for reverse-genetics projects from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (https://abrc.osu.edu/) or the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre (http://www.arabidopsis.info), which maintain sequence-indexed collections of >30,000 homozygous T-DNA insertional lines (O’Malley and Ecker 2010) from hundreds of thousands of insertion events (Alonso et al. 2003). Full-length complementary DNAs for most genes (Yamada et al. 2003) also are available from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center. Further, there are collections of Arabidopsis expression vectors (Curtis and Grossniklaus 2003; Earley et al. 2006) and yeast two-hybrid vectors (Trigg et al. 2017) for conducting overexpression, localization, and interaction studies.

Beyond material resources, there is a wealth of shared Arabidopsis data available on The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR; www.arabidopsis.org), Araport (www.araport.org), and ePlant (Waese et al. 2017; https://bar.utoronto.ca/eplant/). Other shared informational resources include databases of gene expression (Schmid et al. 2005; Kilian et al. 2007; Winter et al. 2007) and protein–protein interactions (Trigg et al. 2017). In the realm of proteomics, available data include protein sequences (Baerenfaller et al. 2008), membrane protein topology (Schwacke et al. 2003), subcellular localization (Hooper et al. 2017), phosphorylation (Sugiyama et al. 2008), and ubiquitination (Kim et al. 2013).

An Educational Model

Arabidopsis is a useful model in the classroom. High school and college students have successfully employed Arabidopsis to explore gravitropism (Kiss et al. 2000), genetics (Zheng 2006), and genomics (Brooks et al. 2011). Experiments with an Arabidopsis relative, a set of Brassica rapa varieties known as Wisconsin fast plants, also are popular for teaching experiments that explore plant development (Williams 1997). Whereas Wisconsin fast plants have larger structures and fast life cycles (Williams 1997), the wealth of bioinformatics resources, mutants, and published studies that Arabidopsis brings to the classroom is unrivaled.

Arabidopsis is almost uniquely suited for undergraduate research projects. Unlike animal model organisms for which the preservation of lineages often involves uninterrupted ongoing work, Arabidopsis seeds can survive for years without attention at room temperature and even longer with refrigeration. Likewise, there are few ethical and safety concerns with experimental design, treatment, and handling of Arabidopsis.

Limitations of the Model

Of course, any single plant species cannot fully embody the characteristics of all others. Arabidopsis allows the analysis of many features of plant development, environmental response, and biochemistry. However, not all genes used by other plants are represented in Arabidopsis (Figure 8). Likewise, some interesting research problems are intractable in Arabidopsis.

The relatively small mass of an Arabidopsis plant, advantageous for genetics, can impede the extraction of measurable amounts of sparse biochemicals, and some interesting metabolites are absent from Arabidopsis altogether. For example, Beta vulgaris (sugar beet) produces betalains, vivid antioxidants (Brockington et al. 2011), and the anticancer drug paclitaxel (Taxol) is present in yew trees (genus Taxus) but not in Arabidopsis (Besumbes et al. 2004). Although Arabidopsis does not produce wood, a related secondary growth process is present (Dolan and Roberts 1995) and can be stimulated by certain manipulations (Zhao et al. 2000).

Some plant cell structures, such as trichomes and chloroplasts, differ in Arabidopsis as well. Trichomes are single-cell extensions from the surfaces of leaves and stems (Figure 3). Although Arabidopsis genetics has elucidated trichome development [reviewed in Pattanaik et al. (2014)], Arabidopsis trichomes do not produce the diverse chemical secretions present in many plant species, including tomato, in which glandular trichomes can be investigated (McDowell et al. 2011). Arabidopsis chloroplasts lack the bacterium-like peptidoglycan cell wall present in many plants and algae, but Arabidopsis harbors genes that appear to encode some, but not all, of the enzymes for peptidoglycan production. Loss of one such Arabidopsis gene in the pathway does not cause any notable phenotype (Hirano et al. 2016), suggesting that the genes are vestiges of a lost peptidoglycan biosynthesis pathway in Arabidopsis.

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi are crucial for nutrient and water absorption and colonize 80% of land plants (Wang and Qiu 2006). Arabidopsis flourishes in aseptic conditions in part because it does not associate with mutualistic arbuscular mycorrhizae (Smith and Read 2008). Despite this absence, Arabidopsis research has revealed many aspects of the strigolactone chemical signals that promote arbuscular mycorrhizae in other plants (Kohlen et al. 2011). Furthermore, although Arabidopsis also does not associate with the endosymbiotic bacteria that fix nitrogen, Arabidopsis is useful for studying root colonization by the mutualistic fungus Piriformospora indica (Jacobs et al. 2011) that can facilitate Arabidopsis phosphate uptake (Shahollari et al. 2005).

Arabidopsis Genetics

Norms and nomenclature

A. thaliana is often indicated simply by the genus name Arabidopsis, even though other species within the genus also are subjects of investigation. Some authors consider Arabidopsis to be a common name, printing the nonitalicized word with or without capitalization. Other English names for the plant, including Thale cress and mouse-ear cress, are rarely used by researchers.

Arabidopsis genes newly identified through mutant analysis are named for the mutant phenotype (Meinke and Koornneef 1997), whereas those identified via reverse genetics are often named for the encoded protein. Gene names are typically abbreviated to three letters. When a gene that has already been described is rediscovered in a new experiment, the previously published name is often used to avoid creating long lists of synonymous gene names. Genes and genotypes are italicized; protein names are not. Wild-type names are written using capital letters; mutant names are lowercase. A locus number follows the letters to distinguish different genes that can mutate to a given phenotype (for genes identified by mutation) or various homologs (for genes identified by homology), and various alleles of the same gene are enumerated following a hyphen. For example, the TRANSPORT INHIBITOR RESPONSE1 (TIR1) gene encodes the TIR1 protein (Ruegger et al. 1998). In this example, the numeral one denotes the first mutant isolated in the transport inhibitor response mutant screen. The tir1-1 protein contains a glycine-to-aspartate change caused by the tir1-1 missense mutation in the tir1-1 mutant, whereas the tir1-9 mutant harbors a T-DNA insertion in the TIR1 gene (Ruegger et al. 1998).

Following the completion of the Arabidopsis sequencing project (Arabidopsis Genome Initiative 2000), genes also have standardized names assigned by TAIR. The standard gene name includes At for A. thaliana, the nuclear chromosome number (or C for chloroplast or M for mitochondrion), and the letter g for gene followed by a unique, five-digit numerical identifier that reflects the chromosomal position. In this system, the TIR1 gene is At3g62980, indicating that the gene is on chromosome 3 with the large number reflecting a position near the bottom of the chromosome. The original annotators spaced the numbers 10 digits apart, leaving room for discovery of genes overlooked in the first annotation.

Independently collected Arabidopsis lineages are known as accessions. Arabidopsis “accessions” are groupings within the species analogous to “breeds” within animal species or “varieties” of crop plants. The differences between accessions range from easily distinguished ecotypes to nearly identical plants that were independently collected and named. The most commonly used wild type is Columbia-0 (Col-0); Landsberg erecta (Ler) and Wassilewskija (Ws) are also commonly studied. Although a number of different accessions of Col-0 may have been used for generating the reference Arabidopsis genome sequence, the Col-0 accession CS70000 has been proposed by TAIR as the reference stock (Huala et al. 2001).

Plant care and growth conditions

Seeds can be germinated directly on the surface of moistened soil. To distribute seeds more evenly when sowing, they can be suspended in a 0.1% (w/v) agar solution and distributed volumetrically using a pipette. It is not necessary to bury the seeds. However, seeds on the soil surface are susceptible to desiccation, and plastic domes or tented plastic wrap can be used to reduce evaporation for the first week or longer. If atmospheric humidity is low, plants may be damaged by sudden removal of the cover, and partially removing the plastic dome or cutting slits in plastic wrap a few days before entirely removing the cover aids survival.

For more carefully controlled experiments, such as those using specific additives or investigating aspects of root development, seedlings can be germinated and grown on sterile media in Petri dishes. For this purpose, seeds are first surface sterilized (gently enough not to kill the embryo) using bleach and detergent (Haughn and Somerville 1986), ethanol (Nelson et al. 2009), or other disinfectants. Two types of media are commonly used: (MS) medium (Murashige and Skoog 1962) and plant nutrient (PN) medium (Haughn and Somerville 1986). MS offers the convenience of commercial, premeasured media packets. PN medium is less convenient, requiring preparation of several stock solutions and mixing of these stocks for each batch of medium (Haughn and Somerville 1986), but offers more user control over the composition of the growth medium. Media may be supplemented with sucrose to promote even germination and to allow the early development of certain metabolic mutants (Pinfield-Wells et al. 2005). Even mutants that require supplemented growth medium for germination can often survive transfer to soil once established (Zolman et al. 2000). Transfer to soil is generally required for a robust seed set.

It is possible to grow Arabidopsis in soil or aseptically on plates in ambient air under common lights, including LED, fluorescent, or incandescent bulbs. Lighted plant growth chambers allow precise control of day length and circulate air to maintain stable, user-defined temperatures while limiting condensation in closed Petri dishes. For experiments testing responses to light or to protect photosensitive chemicals, LED-equipped growth chambers offer fine control of light wavelength and intensity. Alternatively, white light can be filtered through colored plastic sheets (Stasinopoulos and Hangarter 1990), or plates can be wrapped in foil to provide darkness. To test plant responses to other environmental parameters, some incubators can regulate humidity and atmospheric gases such as carbon dioxide.

Arabidopsis plants generally self-pollinate, but the small flowers can be manually crossed with some practice. The ovules of a flower are receptive before the pollen is mature. Therefore, the sepals, petals, and anthers are removed from a recipient (female) unopened flower bud with forceps and then anthers from a mature (open) donor flower are used to dust the exposed stigmatic papillae with pollen. F1 seeds are ready for harvest in ∼2 weeks.

Breakthrough Discoveries Made using Arabidopsis

Many biological processes were first discovered in Arabidopsis (Provart et al. 2016). Other research areas that were initiated in other organisms prompted major discoveries when advanced in Arabidopsis. Below, we sample a few items from the smorgasbord.

Novel insights in biochemistry and plant development

In hot, dry conditions, plants sometimes capture oxygen rather than carbon dioxide during the photosynthetic Calvin–Benson cycle. This photosynthetic flaw impedes the productivity of most crops (Walker et al. 2016). The resulting products can be salvaged in a process called photorespiration, collaboratively achieved by chloroplasts, peroxisomes, and mitochondria (Bauwe et al. 2010). Much of the photorespiratory pathway was revealed using Arabidopsis genetics (Somerville 2001). Furthermore, introducing certain Escherichia coli genes into Arabidopsis decreases the need for photorespiration and increases the efficiency of photosynthesis (Kebeish et al. 2007), providing proof-of-concept work that might be applied to improve crop productivity.

Arabidopsis research was key to developing the ABCE model of floral development (Figure 3). Data from a collection of Arabidopsis and Antirrhinum majus (snapdragon) mutants converged to reveal a set of conserved MADS-box transcription factors that, combined, specify the identity of each whorl (ring) of flower organs (Coen and Meyerowitz 1991). In this model, E-class genes are needed for all floral structures. The combination of A and E activity generates sepals, the leaf-like outer whorl. A, B, and E activity yields petals. B, C, and E activity produces stamens, the pollen-bearing male structures. Finally, C and E activity produces the innermost carpel (female) reproductive structures (Krizek and Fletcher 2005). Developed using Arabidopsis and snapdragon data, the ABCE model of flower development explains floral structures in a variety of plants (Di Stilio 2011).

Arabidopsis offers insight into a host of other plant developmental and cellular processes. One example is the formation of elegant epidermal architecture. Leaves of most plants are decorated with trichomes, or leaf hairs. The isolation of Arabidopsis mutants with sparse or abundant trichomes has revealed that trichome density is regulated by bHLH, MYB, and WD40 transcription factors. The bHLH protein GLABRA3 (GL3) promotes the formation of trichomes (Payne et al. 2000); reduced GL3 expression results in few trichomes, whereas overexpression increases trichome density (Figure 4). Intriguingly, many of the same transcription factors that regulate trichome formation also are used to regulate formation of root hairs (Schellmann et al. 2002), the protrusions from single root epidermal cells that increase root surface area.

Stomata are pores allowing gas exchange that are spaced among the beautifully jigsaw-shaped pavement cells of the leaf epidermis. In stomatal development, the stomagen signaling peptide plays a similar role to GL3 in trichome formation. Decreased stomagen decreases formation of stomata whereas stomagen overexpression increases stomatal density (Figure 5).

Advances in cell and molecular biology

Arabidopsis also offers a window into plant subcellular structures. Although most of the typical eukaryotic organelles are present, there are some special structures, and familiar organelles sometimes take on specialized functions in plant cells. Plastids, including chloroplasts and a variety of other specialized versions, are cyanobacteria-like organelles that conduct photosynthesis but also impart fruit colors, assist in gravity detection, and play key roles in plant metabolism and development. Much fundamental knowledge of plastid function emerged from Arabidopsis (Martin et al. 2002; Singh et al. 2015; van Wijk and Kessler 2017).

Among other fascinating processes, the complex dance of the alternation of generations is subject to dissection in Arabidopsis. Morphologically, this flowering-plant lifestyle involves the formation of male and female gametophytes within the larger sporophyte plant body (Rudall and Bateman 2007). Remarkable processes occur at the cellular level, also. For example, during pollen development the formation of two sperm cells within a surrounding vegetative cell is accompanied by degeneration of the plastids and mitochondria of the vegetative cell (Figure 6). Thus male gametophyte development is reminiscent of animal spermatogenesis, wherein spermatogonia develop within Sertoli cells, and sperm mitochondria usually degenerate after fertilization (Griswold 2016). Unlike in animals, the two sperm cells are used for double fertilization to produce both embryo and endosperm tissues in angiosperm plants (Hamamura et al. 2011).

The first plant microRNAs (miRNAs) were discovered in Arabidopsis (Llave et al. 2002a; Park et al. 2002; Reinhart et al. 2002). ARGONAUTE, a key component of the RNA-Induced Silencing Complex (RISC) through which miRNAs act, was first discovered in Arabidopsis (Bohmert et al. 1998) thanks to the leaf deformities resulting from missing miRNA regulation in the ago1 mutant. Likewise, phased miRNA-directed trans-acting small interfering RNAs were first found in Arabidopsis (Allen et al. 2005). Moreover, the high complementarity between plant miRNAs and their targets allowed systematic, high-confidence miRNA target identification (Rhoades et al. 2002) and validation (Llave et al. 2002b; Mallory et al. 2004) well before such predictions were feasible in metazoans.

Signaling pathway breakthroughs

The diverse discoveries from the field of light response offer a case study in Arabidopsis utility. Although Arabidopsis research has revealed novel proteins and processes, most Arabidopsis research grew up in the shadow of other plants. For example, Charles Darwin and his son Francis conducted pioneering experiments investigating plant phototropisms—growth toward or away from light—in oat (Avena), canary grass, asparagus, and beet, as well as the Arabidopsis cousins white mustard and Brassica oleracea (Darwin and Darwin 1880). It was >100 years before pea proteins were isolated that had characteristics consistent with being a phototropin receptor (Gallagher et al. 1988). Ultimately, the gene encoding the blue-light photoreceptor responsible for phototropism, NPH1/PHOT1, was identified via analysis of an Arabidopsis mutant that was blind to blue light (Liscum and Briggs 1995), and the photoresponsiveness of the Arabidopsis protein was confirmed in an insect heterologous system (Christie et al. 1998).

Plant hormone research is also rooted in the Darwin tropism experiments. The Darwins interpreted their data to “imply the presence of some matter in the upper part which is acted on by light, and which transmits its effects to the lower part” (Darwin and Darwin 1880). Indeed, subsequent experiments in oat revealed a diffusible chemical signal (Went 1926), later named auxin (Kögl and Haagen Smit 1931). The long-sought receptors for auxin were discovered via genetic approaches in Arabidopsis (Ruegger et al. 1998; Dharmasiri et al. 2005; Kepinski and Leyser 2005). Interestingly, the auxin receptors belong to a class of proteins not previously suspected to act as receptors. F-box proteins are the specificity-determining components of Skp1-Cullin-F-box (SCF) complexes that target proteins for ubiquitination and degradation (Zheng et al. 2002). The receptor role was first discovered for the Arabidopsis TRANSPORT INHIBITOR RESPONSE1 (TIR1) F-box protein that is sufficient to target AUX/IAA transcriptional repressors for degradation in heterologous systems (Dharmasiri et al. 2005; Kepinski and Leyser 2005). Likewise, the F-box CORONATINE-INSENSITIVE1 (COI1) protein, also discovered through Arabidopsis forward genetics, is a receptor for the jasmonate phytohormone (Sheard et al. 2010). In a fascinating parallel, auxin and jasmonate (jasmonoyl-l-isoleucine) molecules bind between the F-box protein and the targeted repressor, stabilizing the interaction to ensure target protein ubiquitination and degradation (Tan et al. 2007; Sheard et al. 2010). Both the F-box and the target protein participate in hormone binding and can therefore be considered coreceptors. Like with auxin and jasmonate, the hormones gibberellin and strigolactone also signal through F-box proteins that promote the destruction of repressors in the corresponding pathways (Morffy et al. 2016).

Arabidopsis mutants that fail to respond appropriately to the absence of light allowed the discovery of the COP9 signalosome, a multiprotein complex that regulates ubiquitination enzymes. The de-etiolated (det) and constitutive photomorphogenic (cop) mutants develop in darkness as if they were growing in light: In darkness, these mutants expand their cotyledons, fail to elongate their hypocotyls (embryo-derived stems), and accumulate the normally light-induced anthocyanin pigments (Chory et al. 1989; Deng et al. 1991). In fact, several of these cop and det mutants are allelic with fusca (fus) mutants that were isolated because they accumulate excess anthocyanins in seeds (Müller 1963; Castle and Meinke 1994). The genes identified in these Arabidopsis mutant screens encode the founding members of the COP9 protein regulatory complex (Wei and Deng 1992, 2003). Later discovered in other organisms, the COP9 signalosome is now of key interest in cancer formation and therapy (Schlierf et al. 2016).

Insights from Comparing Arabidopsis to Other Organisms

Arabidopsis is also an effective platform for reverse-genetic research. In one application of reverse genetics, a documented function in another organism inspires a hypothesis of similar function for the closest-related Arabidopsis genes (Krysan et al. 1996). For example, components of the autophagy pathway involved in degrading cellular aggregates and organelles were first identified in yeast (Tsukada and Ohsumi 1993). When mutants carrying T-DNA insertions in the closest Arabidopsis homologs of yeast autophagy genes were examined, autophagy-defective phenotypes were indeed observed (Phillips et al. 2008). This work allowed the discovery of plant-specific roles for autophagy, including recovery from darkness-induced starvation (Figure 7; Phillips et al. 2008).

Arabidopsis data and components have been used in translational projects in crop plants. For example, the Arabidopsis transcription factor MYB12 stimulates the production of flavonol chemicals (Mehrtens et al. 2005). Flavonol intake is correlated with markers of cardiovascular health (Perez-Vizcaino and Duarte 2010), so increasing crop flavonol content is an attractive ambition. Expressing Arabidopsis MYB12 in tomato had the hypothesized effect of increasing flavonol content, profoundly enough to change fruit color from red to orange (Figure 9; Luo et al. 2008).

Research using Arabidopsis has greatly expanded our knowledge of plants—the organisms that provide most human nutrition and atmospheric oxygen—and revealed key, common processes in diverse organisms beyond plants. With the application of inexpensive whole-genome sequencing (Ossowski et al. 2010; Yamamoto et al. 2010) and CRISPR/Cas9-based gene editing tools (Jiang et al. 2013; Li et al. 2013), many plants are now amenable to analysis that was once only feasible in Arabidopsis. Nonetheless, the depth of understanding and ease of manipulation in the Arabidopsis system is unrivaled, and Arabidopsis will remain the reference plant for the foreseeable future. Careful cultivation of an obscure garden weed has taught us much about both the garden and the gardener.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jin Suk Lee, Keiko Torii, and Richard Vierstra for images and Abigail Garcia, Kim Gonzalez, Kathryn Hamilton, Yun-Ting Kao, Roxanna Llinas, Michael Passalacqua, Melissa Traver, Pierce Young, Zachary Wright, and two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on the manuscript and Dominic Palesch for assistance with translation. We apologize to the many Arabidopsis researchers whose work we could not highlight in this sampling because of length limitations. Our research is funded by faculty development grants from The University of Mary Hardin-Baylor Provost (to A.W.W.), the National Institutes of Health (R01GM079177 to B.B.), the National Science Foundation (MCB-1516966 to B.B.), and the Robert A. Welch Foundation (C-1309 to B.B.).

Footnotes

Communicating editor: E. De Stasio

Literature Cited

- Allen E., Xie Z., Gustafson A. M., Carrington J. C., 2005. microRNA-directed phasing during trans-acting siRNA biogenesis in plants. Cell 121: 207–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso J. M., Stepanova A. N., Leisse T. J., Kim C. J., Chen H., et al. , 2003. Genome-wide insertional mutagenesis of Arabidopsis thaliana. Science 301: 653–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arabidopsis Genome Initiative , 2000. Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature 408: 796–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baerenfaller K., Grossmann J., Grobei M. A., Hull R., Hirsch-Hoffmann M., et al. , 2008. Genome-scale proteomics reveals Arabidopsis thaliana gene models and proteome dynamics. Science 320: 938–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauwe H., Hagemann M., Fernie A. R., 2010. Photorespiration: players, partners and origin. Trends Plant Sci. 15: 330–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besumbes O., Sauret-Güeto S., Phillips M. A., Imperial S., Rodríguez-Concepción M., et al. , 2004. Metabolic engineering of isoprenoid biosynthesis in Arabidopsis for the production of taxadiene, the first committed precursor of Taxol. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 88: 168–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell R. D., Murray A. J., Lea P. J., Kendall A. C., Hall N. P., et al. , 1988. The value of mutants unable to carry out photorespiration. Photosynth. Res. 16: 155–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohmert K., Camus I., Bellini C., Bouchez D., Caboche M., et al. , 1998. AGO1 defines a novel locus of Arabidopsis controlling leaf development. EMBO J. 17: 170–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun A., 1873. Sitzungs-bericht der gesellschaft naturforschender freunde zu Berlin. 75.

- Brockington S. F., Walker R. H., Glover B. J., Soltis P. S., Soltis D. E., 2011. Complex pigment evolution in the Caryophyllales. New Phytol. 190: 854–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks E., Dolan E., Tax F., 2011. Partnership for research & education in plants (PREP): involving high school students in authentic research in collaboration with scientists. Am. Biol. Teach. 73: 137–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castle L. A., Meinke D. W., 1994. A FUSCA gene of Arabidopsis encodes a novel protein essential for plant development. Plant Cell 6: 25–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C., Kwok S. F., Bleecker A. B., Meyerowitz E. M., 1993. Arabidopsis ethylene-response gene ETR1: similarity of product to two-component regulators. Science 262: 539–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C. Y., Krishnakumar V., Chan A. P., Thibaud-Nissen F., Schobel S., et al. , 2017. Araport11: a complete reannotation of the Arabidopsis thaliana reference genome. Plant J. 89: 789–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chory J., Peto C., Feinbaum R., Pratt L., Ausubel F., 1989. Arabidopsis thaliana mutant that develops as a light-grown plant in the absence of light. Cell 58: 991–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie J. M., Reymond P., Powell G. K., Bernasconi P., Raibekas A. A., et al. , 1998. Arabidopsis NPH1: a flavoprotein with the properties of a photoreceptor for phototropism. Science 282: 1698–1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough S. J., Bent A. F., 1998. Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16: 735–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coen E. S., Meyerowitz E. M., 1991. The war of the whorls: genetic interactions controlling flower development. Nature 353: 31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis M. D., Grossniklaus U., 2003. A gateway cloning vector set for high-throughput functional analysis of genes in planta. Plant Physiol. 133: 462–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis W., 1777. Flora Londinensis: Or Plates and Descriptions of Such Plants as Grow Wild in the Environs of London. W. Curtis and B. White, London. [Google Scholar]

- Darwin C., Darwin F., 1880. The Power of Movement in Plants. John Murray, London. [Google Scholar]

- De Candolle A. P., 1824. Prodromus systematis naturalis regni vegetabilis. Treuttel and Würtz, Paris. [Google Scholar]

- Deng X.-W., Caspar T., Quail P. H., 1991. cop1: a regulatory locus involved in light-controlled development and gene expression in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 5: 1172–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dharmasiri N., Dharmasiri S., Estelle M., 2005. The F-box protein TIR1 is an auxin receptor. Nature 435: 441–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Stilio V. S., 2011. Empowering plant evo-devo: virus induced gene silencing validates new and emerging model systems. BioEssays 33: 711–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doebley J., Stec A., Gustus C., 1995. teosinte branched1 and the origin of maize: evidence for epistasis and the evolution of dominance. Genetics 141: 333–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan L., Roberts K., 1995. Secondary thickening in roots of Arabidopsis thaliana: anatomy and cell surface changes. New Phytol. 131: 121–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earley K. W., Haag J. R., Pontes O., Opper K., Juehne T., et al. , 2006. Gateway-compatible vectors for plant functional genomics and proteomics. Plant J. 45: 616–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher S., Short T. W., Ray P. M., Pratt L. H., Briggs W. R., 1988. Light-mediated changes in two proteins found associated with plasma membrane fractions from pea stem sections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85: 8003–8007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greuter W., Burdet H. M., Chaloner W. G., Demoulin V., Grolle R., et al. , 1988. International Code of Botanical Nomenclature Adopted by the Fourteenth International Botanical Congree, Berlin, July-August 1987. Koeltz Scientific Books, Königstein, Federal Republic of Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Griswold M. D., 2016. Spermatogenesis: the commitment to meiosis. Physiol. Rev. 96: 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamamura Y., Saito C., Awai C., Kurihara D., Miyawaki A., et al. , 2011. Live-cell imaging reveals the dynamics of two sperm cells during double fertilization in Arabidopsis thaliana. Curr. Biol. 21: 497–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haughn G. W., Somerville C., 1986. Sulfonylurea-resistant mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Gen. Genet. 204: 430–434. [Google Scholar]

- Hirano T., Tanidokoro K., Shimizu Y., Kawarabayasi Y., Ohshima T., et al. , 2016. Moss chloroplasts are surrounded by a peptidoglycan wall containing D-amino acids. Plant Cell 28: 1521–1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann M. H., 2002. Biogeography of Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. (Brassicaceae). J. Biogeogr. 29: 125–134. [Google Scholar]

- Hogge L. R., Reed D. W., Underhill E. W., Haughn G. W., 1988. HPLC separation of glucosinolates from leaves and seeds of Arabidopsis thaliana and their identification using thermospray liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 26: 551–556. [Google Scholar]

- Hohmann N., Wolf E. M., Lysak M. A., Koch M. A., 2015. A time-calibrated road map of Brassicaceae species radiation and evolutionary history. Plant Cell 27: 2770–2784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holl F., Heynhold G., 1842. Flora von Sachsen. Justus Naumann, Dresden, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper C. M., Castleden I. R., Tanz S. K., Aryamanesh N., Millar A. H., 2017. SUBA4: the interactive data analysis centre for Arabidopsis subcellular protein locations. Nucleic Acids Res. 45: D1064–D1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huala E., Dickerman A. W., Garcia-Hernandez M., Weems D., Reiser L., et al. , 2001. The Arabidopsis information resource (TAIR): a comprehensive database and web-based information retrieval, analysis, and visualization system for a model plant. Nucleic Acids Res. 29: 102–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs S., Zechmann B., Molitor A., Trujillo M., Petutschnig E., et al. , 2011. Broad-spectrum suppression of innate immunity is required for colonization of Arabidopsis roots by the fungus Piriformospora indica. Plant Physiol. 156: 726–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W., Zhou H., Bi H., Fromm M., Yang B., et al. , 2013. Demonstration of CRISPR/Cas9/sgRNA-mediated targeted gene modification in Arabidopsis, tobacco, sorghum and rice. Nucleic Acids Res. 41: e188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kebeish R., Niessen M., Thiruveedhi K., Bari R., Hirsch H.-J., et al. , 2007. Chloroplastic photorespiratory bypass increases photosynthesis and biomass production in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat. Biotechnol. 25: 593–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kepinski S., Leyser O., 2005. The Arabidopsis F-box protein TIR1 is an auxin receptor. Nature 435: 446–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilian J., Whitehead D., Horak J., Wanke D., Weinl S., et al. , 2007. The AtGenExpress global stress expression data set: protocols, evaluation and model data analysis of UV-B light, drought and cold stress responses. Plant J. 50: 347–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. Y., Scalf M., Smith L. M., Vierstra R. D., 2013. Advanced proteomic analyses yield a deep catalog of ubiquitylation targets in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25: 1523–1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss J. Z., Weise S. E., Kiss H. G., 2000. How can plants tell which way is up? Laboratory exercises to introduce gravitropism. Am. Biol. Teach. 62: 59–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kögl F., Haagen Smit A. J., 1931. Über die Chemie des Wuchsstoffs. K. Akad. Wetenschap. Amsterdam Proc. Sect. Sci. 34: 1411–1416. [Google Scholar]

- Kohlen W., Charnikhova T., Liu Q., Bours R., Domagalska M. A., et al. , 2011. Strigolactones are transported through the xylem and play a key role in shoot architectural response to phosphate deficiency in nonarbuscular mycorrhizal host Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 155: 974–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koornneef M., Van Der Veen J. H., 1980. Induction and analysis of gibberellin sensitive mutants in Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. Theor. Appl. Genet. 58: 257–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krizek B. A., Fletcher J. C., 2005. Molecular mechanisms of flower development: an armchair guide. Nat. Rev. Genet. 6: 688–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krysan P. J., Young J. C., Tax F., Sussman M. R., 1996. Identification of transferred DNA insertions within Arabidopsis genes involved in signal transduction and ion transport. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93: 8145–8150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laibach F., 1907. Zur frage nach der individualität der chromosomen im pflanzenreich. Beih. Botan. Zentralbl. 22: 191–210. [Google Scholar]

- Langridge J., 1955. Biochemical mutations in the crucifer Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. Nature 176: 260–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. S., Hnilova M., Maes M., Lin Y. C., Putarjunan A., et al. , 2015. Competitive binding of antagonistic peptides fine-tunes stomatal patterning. Nature 522: 439–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.-F., Norville J. E., Aach J., Mccormack M., Zhang D., et al. , 2013. Multiplex and homologous recombination-mediated genome editing in Arabidopsis and Nicotiana benthamiana using guide RNA and Cas9. Nat. Biotechnol. 31: 688–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnaeus C., 1753. Species plantarum. Laurentius Salvius, Stockholm. [Google Scholar]

- Liscum E., Briggs W. R., 1995. Mutations in the NPH1 locus of Arabidopsis disrupt the perception of phototropic stimuli. Plant Cell 7: 473–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llave C., Kasschau K. D., Rector M. A., Carrington J. C., 2002a Endogenous and silencing-associated small RNAs in plants. Plant Cell 14: 1605–1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llave C., Xie Z., Kasschau K. D., Carrington J. C., 2002b Cleavage of Scarecrow-like mRNA targets directed by a class of Arabidopsis miRNA. Science 297: 2053–2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd A. M., Barnason A. R., Rogers S. G., Byrne M. C., Fraley R. T., et al. , 1986. Transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana with Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Science 234: 464–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J., Butelli E., Hill L., Parr A., Niggeweg R., et al. , 2008. AtMYB12 regulates caffeoyl quinic acid and flavonol synthesis in tomato: expression in fruit results in very high levels of both types of polyphenol. Plant J. 56: 316–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallory A. C., Dugas D. V., Bartel D. P., Bartel B., 2004. MicroRNA regulation of NAC-domain targets is required for proper formation and separation of adjacent embryonic, vegetative, and floral organs. Curr. Biol. 14: 1035–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin W., Rujan T., Richly E., Hansen A., Cornelsen S., et al. , 2002. Evolutionary analysis of Arabidopsis, cyanobacterial, and chloroplast genomes reveals plastid phylogeny and thousands of cyanobacterial genes in the nucleus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99: 12246–12251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushima R., Tang L. Y., Zhang L., Yamada H., Twell D., et al. , 2011. A conserved, Mg(2)+-dependent exonuclease degrades organelle DNA during Arabidopsis pollen development. Plant Cell 23: 1608–1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell E. T., Kapteyn J., Schmidt A., Li C., Kang J.-H., et al. , 2011. Comparative functional genomic analysis of Solanum glandular trichome types. Plant Physiol. 155: 524–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKelvie A. D., 1962. A list of mutant genes in Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. Radiat. Bot. 1: 233–241. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrtens F., Kranz H., Bednarek P., Weisshaar B., 2005. The Arabidopsis transcription factor MYB12 is a flavonol-specific regulator of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 138: 1083–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinke D., Koornneef M., 1997. Community standards for Arabidopsis genetics. Plant J. 12: 247–253. [Google Scholar]

- Meyerowitz E. M., Pruitt R. E., 1985. Arabidopsis thaliana and plant molecular genetics. Science 229: 1214–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell-Olds T., 2001. Arabidopsis thaliana and its wild relatives: a model system for ecology and evolution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 16: 693–700. [Google Scholar]

- Morffy N., Faure L., Nelson D. C., 2016. Smoke and hormone mirrors: action and evolution of karrikin and strigolactone signaling. Trends Genet. 32: 176–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller A. J., 1963. Embryonentest zum Nachweis Rezessiver Letalfaktoren bei Arabidopsis thaliana. Biol Zbl 82: 133–163. [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T., Skoog F., 1962. A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol. Plant. 15: 473–497. [Google Scholar]

- NCBI Resource Coordinators , 2017. Database resources of the national center for biotechnology information. Nucleic Acids Res. 45: D12–D17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson D. C., Riseborough J.-A., Flematti G. R., Stevens J., Ghisalberti E. L., et al. , 2009. Karrikins discovered in smoke trigger Arabidopsis seed germination by a mechanism requiring gibberellic acid synthesis and light. Plant Physiol. 149: 863–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley R. C., Ecker J. R., 2010. Linking genotype to phenotype using the Arabidopsis unimutant collection. Plant J. 61: 928–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ossowski S., Schneeberger K., Lucas-Lledó J. I., Warthmann N., Clark R. M., et al. , 2010. The rate and molecular spectrum of spontaneous mutations in Arabidopsis thaliana. Science 327: 92–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özkan H., Brandolini A., Schäfer-Pregl R., Salamini F., 2002. AFLP analysis of a collection of tetraploid wheats indicates the origin of emmer and hard wheat domestication in southeast Turkey. Mol. Biol. Evol. 19: 1797–1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park W., Li J., Song R., Messing J., Chen X., 2002. CARPEL FACTORY, a Dicer homolog, and HEN1, a novel protein, act in microRNA metabolism in Arabidopsis thaliana. Curr. Biol. 12: 1484–1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson A. H., Bowers J. E., Bruggmann R., Dubchak I., Grimwood J., et al. , 2009. The Sorghum bicolor genome and the diversification of grasses. Nature 457: 551–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattanaik S., Patra B., Singh S. K., Yuan L., 2014. An overview of the gene regulatory network controlling trichome development in the model plant, Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 5: 259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne C. T., Zhang F., Lloyd A. M., 2000. GL3 encodes a bHLH protein that regulates trichome development in Arabidopsis through interaction with GL1 and TTG1. Genetics 156: 1349–1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Vizcaino F., Duarte J., 2010. Flavonols and cardiovascular disease. Mol. Aspects Med. 31: 478–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrier X., De Langhe E., Donohue M., Lentfer C., Vrydaghs L., et al. , 2011. Multidisciplinary perspectives on banana (Musa spp.) domestication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108: 11311–11318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips A. R., Suttangkakul A., Vierstra R. D., 2008. The ATG12-conjugating enzyme ATG10 is essential for autophagic vesicle formation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics 178: 1339–1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinfield-Wells H., Rylott E. L., Gilday A. D., Graham S., Job K., et al. , 2005. Sucrose rescues seedling establishment but not germination of Arabidopsis mutants disrupted in peroxisomal fatty acid catabolism. Plant J. 43: 861–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provart N. J., Alonso J., Assmann S. M., Bergmann D., Brady S. M., et al. , 2016. 50 years of Arabidopsis research: highlights and future directions. New Phytol. 209: 921–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp R. A., Haigler C. H., Flagel L., Hovav R. H., Udall J. A., et al. , 2010. Gene expression in developing fibres of Upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) was massively altered by domestication. BMC Biol. 8: 139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rédei G. P., 1962. Supervital mutants of Arabidopsis. Genetics 47: 443–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rédei G. P., 1975. Arabidopsis as a genetic tool. Annu. Rev. Genet. 9: 111–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhart B. J., Weinstein E. G., Rhoades M. W., Bartel B., Bartel D. P., 2002. MicroRNAs in plants. Genes Dev. 16: 1616–1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinholz E., 1947. Åuslösung von röntgenmutationen bei Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. und ihre bedeutung für die pflanzenzüchtung und evolutionstheorie.

- Rhoades M. W., Reinhart B. J., Lim L. P., Burge C. B., Bartel B., et al. , 2002. Prediction of plant microRNA targets. Cell 110: 513–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudall P. J., Bateman R. M., 2007. Developmental bases for key innovations in the seed-plant microgametophyte. Trends Plant Sci. 12: 317–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruegger M., Dewey E., Gray W. M., Hobbie L., Turner J., et al. , 1998. The TIR1 protein of Arabidopsis functions in auxin response and is related to human SKP2 and yeast Grr1p. Genes Dev. 12: 198–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rydberg P. A., 1907. The genus Pilosella in North America. Torreya 7: 157–162. [Google Scholar]

- Schellmann S., Schnittger A., Kirik V., Wada T., Okada K., et al. , 2002. TRIPTYCHON and CAPRICE mediate lateral inhibition during trichome and root hair patterning in Arabidopsis. EMBO J. 21: 5036–5046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlierf A., Altmann E., Quancard J., Jefferson A. B., Assenberg R., et al. , 2016. Targeted inhibition of the COP9 signalosome for treatment of cancer. Nat. Commun. 7: 13166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid M., Davison T. S., Henz S. R., Pape U. J., Demar M., et al. , 2005. A gene expression map of Arabidopsis thaliana development. Nat. Genet. 37: 501–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneeberger K., Ossowski S., Lanz C., Juul T., Petersen A. H., et al. , 2009. SHOREmap: simultaneous mapping and mutation identification by deep sequencing. Nat. Methods 6: 550–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwacke R., Schneider A., Van Der Graaff E., Fischer K., Catoni E., et al. , 2003. ARAMEMNON, a novel database for Arabidopsis integral membrane proteins. Plant Physiol. 131: 16–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahollari B., Varma A., Oelmüller R., 2005. Expression of a receptor kinase in Arabidopsis roots is stimulated by the basidiomycete Piriformospora indica and the protein accumulates in Triton X-100 insoluble plasma membrane microdomains. J. Plant Physiol. 162: 945–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheard L. B., Tan X., Mao H., Withers J., Ben-Nissan G., et al. , 2010. Jasmonate perception by inositol-phosphate-potentiated COI1-JAZ co-receptor. Nature 468: 400–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R., Singh S., Parihar P., Singh V. P., Prasad S. M., 2015. Retrograde signaling between plastid and nucleus: a review. J. Plant Physiol. 181: 55–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. E., Read D. J., 2008. Mycorrhizal symbiosis. Academic Press, San Diego. [Google Scholar]

- Somerville C. R., 2001. An early Arabidopsis demonstration. Resolving a few issues concerning photorespiration. Plant Physiol. 125: 20–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville C. R., Ogren W. L., 1979. A phosphoglycolate phosphatase-deficient mutant of Arabidopsis. Nature 280: 833–836. [Google Scholar]

- Stasinopoulos T. C., Hangarter R. P., 1990. Preventing photochemistry in culture media by long-pass light filters alters growth of cultured tissues. Plant Physiol. 93: 1365–1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama N., Nakagami H., Mochida K., Daudi A., Tomita M., et al. , 2008. Large-scale phosphorylation mapping reveals the extent of tyrosine phosphorylation in Arabidopsis. Mol. Syst. Biol. 4: 193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan X., Calderon-Villalobos L. I., Sharon M., Zheng C., Robinson C. V., et al. , 2007. Mechanism of auxin perception by the TIR1 ubiquitin ligase. Nature 446: 640–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanksley S. D., Mccouch S. R., 1997. Seed banks and molecular maps: unlocking genetic potential from the wild. Science 277: 1063–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thal J., 1588. Sylva Hercynia, sive catalogus plantarum sponte nascentium in montibus, et locis vicinis Hercyniae, quae respicit Soxoniam. Frankfurt am Main. [Google Scholar]

- Timofeev-Resovskii N. V., Ginter E. K., Glotov N. V., Ivanov V. I., 1971. Genetic and somatic effects of X-rays and fast neutrons in experiments on Arabidopsis and Drosophila. Sov. Genet. 7: 446–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titova N. N., 1935. Sovietskaya Botanika 2: 61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Trigg S. A., Garza R. M., Macwilliams A., Nery J. R., Bartlett A., et al. , 2017. CrY2H-seq: a massively multiplexed assay for deep-coverage interactome mapping. Nat. Methods 14: 819–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukada M., Ohsumi Y., 1993. Isolation and characterization of autophagy-defective mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 333: 169–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wijk K. J., Kessler F., 2017. Plastoglobuli: plastid microcompartments with integrated functions in metabolism, plastid developmental transitions, and environmental adaptation. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 68: 253–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waese J., Fan J., Pasha A., Yu H., Fucile G., et al. , 2017. ePlant: visualizing and exploring multiple levels of data for hypothesis generation in plant biology. Plant Cell 29: 1806–1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker B. J., Vanloocke A., Bernacchi C. J., Ort D. R., 2016. The costs of photorespiration to food production now and in the future. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 67: 107–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Qiu Y.-L., 2006. Phylogenetic distribution and evolution of mycorrhizas in land plants. Mycorrhiza 16: 299–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei N., Deng X.-W., 1992. COP9: a new genetic locus involved in light-regulated development and gene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 4: 1507–1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei N., Deng X. W., 2003. The COP9 signalosome. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 19: 261–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Went F. W., 1926. On growth-accelerating substances in the coleoptile of Avena sativa. Proc. K. Ned. Akad. Wet. 30: 10–19. [Google Scholar]

- Williams P., 1997. Expoloring with Wisconsin Fast Plants. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company, Dubuque, IA. [Google Scholar]

- Winter D., Vinegar B., Nahal H., Ammar R., Wilson G. V., et al. , 2007. An “Electronic Fluorescent Pictograph” browser for exploring and analyzing large-scale biological data sets. PLoS One 2: e718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yajko D. M., Hegeman G. D., 1971. Tumor induction by Agrobacterium tumefaciens: specific transfer of bacterial deoxyribonucleic acid to plant tissue. J. Bacteriol. 108: 973–979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K., Lim J., Dale J. M., Chen H., Shinn P., et al. , 2003. Empirical analysis of transcriptional activity in the Arabidopsis genome. Science 302: 842–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T., Nagasaki H., Yonemaru J., Ebana K., Nakajima M., et al. , 2010. Fine definition of the pedigree haplotypes of closely related rice cultivars by means of genome-wide discovery of single-nucleotide polymorphisms. BMC Genomics 11: 267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C., Johnson B. J., Kositsup B., Beers E. P., 2000. Exploiting secondary growth in Arabidopsis. Construction of xylem and bark cDNA libraries and cloning of three xylem endopeptidases. Plant Physiol. 123: 1185–1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Butelli E., Alseekh S., Tohge T., Rallapalli G., et al. , 2015. Multi-level engineering facilitates the production of phenylpropanoid compounds in tomato. Nat. Commun. 6: 8635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng N., Schulman B. A., Song L., Miller J. J., Jeffrey P. D., et al. , 2002. Structure of the Cul1-Rbx1-Skp1-F boxSkp2 SCF ubiquitin ligase complex. Nature 416: 703–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Z.-L., 2006. Use of the gl1 mutant & the CA-rop2 transgenic plants of Arabidopsis thaliana in the biology laboratory course. Am. Biol. Teach. 68: e148–e153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolman B. K., Yoder A., Bartel B., 2000. Genetic analysis of indole-3-butyric acid responses in Arabidopsis thaliana reveals four mutant classes. Genetics 156: 1323–1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]