Abstract

The ability to predict the agronomic performance of single-crosses with high precision is essential for selecting superior candidates for hybrid breeding. With recent technological advances, thousands of new parent lines, and, consequently, millions of new hybrid combinations are possible in each breeding cycle, yet only a few hundred can be produced and phenotyped in multi-environment yield trials. Well established prediction approaches such as best linear unbiased prediction (BLUP) using pedigree data and whole-genome prediction using genomic data are limited in capturing epistasis and interactions occurring within and among downstream biological strata such as transcriptome and metabolome. Because mRNA and small RNA (sRNA) sequences are involved in transcriptional, translational and post-translational processes, we expect them to provide information influencing several biological strata. However, using sRNA data of parent lines to predict hybrid performance has not yet been addressed. Here, we gathered genomic, transcriptomic (mRNA and sRNA) and metabolomic data of parent lines to evaluate the ability of the data to predict the performance of untested hybrids for important agronomic traits in grain maize. We found a considerable interaction for predictive ability between predictor and trait, with mRNA data being a superior predictor for grain yield and genomic data for grain dry matter content, while sRNA performed relatively poorly for both traits. Combining mRNA and genomic data as predictors resulted in high predictive abilities across both traits and combining other predictors improved prediction over that of the individual predictors alone. We conclude that downstream “omics” can complement genomics for hybrid prediction, and, thereby, contribute to more efficient selection of hybrid candidates.

Keywords: BLUP, hybrid performance, maize, omics, genomic prediction, genomic selection, GenPred, Shared Data Resources, Genomic Selection

HYBRID breeding has considerably advanced yields in crops such as maize, rice, sorghum, pearl millet, rye, sugar beet, and sunflower (Duvick 1999). To exploit heterosis in an optimal manner, parent lines are organized in genetically distinct heterotic groups (Melchinger and Gumber 1998; Reif et al. 2007). Each breeding cycle results in large numbers of new inbred parents, especially if line development is based on the doubled haploid (DH) technology (Wedzony et al. 2009) or on rapid cycles of recurrent selfing by single seed descent (SSD). Any possible combination of two lines from different groups can potentially yield a unique single-cross hybrid that may result in a new cultivar. Together with the large number of available parent lines (around n = 1000 or more per heterotic group), this poses a great challenge to plant breeders, who must then select the superior ones from n2 potential hybrid candidates. From these numbers it becomes obvious that it is economically and logistically impossible to evaluate the phenotypic performance of all n2 hybrid candidates in multi-environment field trials.

Previous studies have shown that genotypic value of untested hybrid candidates can be successfully forecast using predictors collected on the 2n parent lines as the basis of a statistical model trained with an only moderately sized subset of hybrids with phenotypic data (Bernardo 1994; Massman et al. 2013; Technow et al. 2014; Kadam et al. 2016). Traditionally, pedigree and genomic information on the parent lines have been used for predictions of breeding values, and the majority of studies in the past decade focused on conceiving and improving algorithms for exploiting the full potential of these data (Meuwissen et al. 2001; Maenhout et al. 2010; Habier et al. 2011). Best linear unbiased prediction (BLUP) was initially developed for animal breeding (Henderson 1984), and later established in plant breeding by Bernardo (1994). As an approach for polygenic traits, BLUP shrinks all effects equally and uses the degree of relatedness, based on pedigree information, to predict breeding values. However, coancestry coefficients calculated from pedigree data are expectations, and can deviate from the realized relationship between individuals because pairs of founder genotypes are considered unrelated and Mendelian sampling is neglected, as are the effects of selection (Cox et al. 1986; Speed and Balding 2015). Genomic information addresses these issues but captures the activity of genes only imperfectly through linkage (Schopp et al. 2017). Moreover, statistical models used in genomic prediction are limited in capturing physiological epistasis (Sackton and Hartl 2016), such as pervasive interactions between loci throughout the genome (Brem et al. 2005; Brown et al. 2014).

Recently, research turned toward exploring the predictive value of intermediary biological strata in the cascade from genotype to phenotype, expecting these would capture gene activities and integrate interactions within and among upstream strata. The transcriptome reflects the active part of the genome by quantifying gene expression and has displayed promising properties for predicting yield performance in both maize inbred lines (Guo et al. 2016) and hybrids (Westhues et al. 2017; Zenke-Philippi et al. 2017). As the final stratum in the biological cascade, the metabolome might be expected to integrate all previous processes and interactions. It has indeed yielded promising predictive abilities for lines (Guo et al. 2016) and testcrosses (Riedelsheimer et al. 2012) in maize, and for hybrids in rice (Xu et al. 2016) and maize (Westhues et al. 2017), when metabolites were sampled from plant tissue at an early development stage. In this study, for the first time, we augment the repertoire of “omics” predictors with small RNA (sRNA) sequences expected to further improve prediction of hybrid performance due to their involvement in transcriptional, post-transcriptional, and translational processes of gene regulation (Lappalainen et al. 2013; Franks et al. 2017; Li et al. 2017).

In practical breeding programs, only pedigree and genomic data are currently established for routine analyses and applications. It is therefore of great interest to compare genomic with other “omics” data regarding their ability to predict hybrid performance in a dataset that represents an applied hybrid breeding program with important agronomic traits. Major questions include how consistently single predictors perform for different traits, and whether combining predictors provides high predictive ability more consistently across traits, due to complementation of positive properties. In addition, determining the impact of individual predictors within such combined predictors is of interest.

Our objectives were to (i) compare the performance of “omics” or pedigree data as single predictors for the prediction of hybrid performance and (ii) investigate the benefit of combining them in major agronomic traits of grain maize by using multi-environmental phenotypic data of hybrids together with pedigree, genomic, transcriptomic, and metabolic data of their parent lines.

Materials and Methods

Genetic material and agronomic data

A set of 1567 hybrids, denoted as HTot, was produced in 16 factorial mating designs between 143 Dent and 104 Flint lines from the maize breeding program at the University of Hohenheim (Stuttgart, Germany). The present study is an extension of the publication of Technow et al. (2014) who analyzed a subset of factorials for hybrid prediction on the basis of genomic data only. All HTot hybrids were evaluated in field experiments between 1999 and 2014 at 4–10 (median: 7) agro-ecologically diverse environments across Germany. In the trials of each factorial, which included at least five common check genotypes, entries were randomized in field designs with incomplete blocks (α-lattice design, Patterson and Williams 1976) and planted in two-row plots. Traits determined were grain dry matter yield (GY, in tons per hectare), adjusted to 155‰ grain moisture, and grain dry matter content (GDMC, in percent). For a subset comprising 50 Dent and 41 Flint inbred lines, denoted as D = {1, 2, . . ., 50} and F = {1, 2, . . ., 41}, data of all subsequently described predictors were available. To ensure that comparisons among different predictor data types were carried out using identical sets of genotypes for all involved predictors, the initial HTot was restricted to the subset of crosses between D and F, resulting in a core dataset H ⊂ HTot, comprising 550 hybrids. These core set hybrids H, for which all five predictor data types were available for both respective parents, were used for hybrid prediction. Pedigree-based relationship coefficients.

Pedigree data

Pedigree data (P) were analyzed for all parent lines at least back to the generation of their grandparents. Coancestry coefficients (Falconer and Mackay 1996) were calculated for all pairs of lines within each heterotic group using SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute) as detailed in Westhues et al. (2017).

Endophenotypes

Genomic SNP data (G) of all inbred lines were obtained with the Illumina SNP chip MaizeSNP50 (Ganal et al. 2011). After performing quality checks as described by Technow et al. (2014) and imputation of the remaining 0.9% missing data points (Browning and Browning 2009), a set of 37,392 polymorphic SNPs was obtained and used for all further analyses.

Transcriptomic mRNA data (T) of all parent lines were gathered as detailed by Westhues et al. (2017). Briefly, five seedlings per line were grown in a climate chamber. Seven days after sowing, whole seedlings were sampled, frozen in liquid nitrogen, pooled, and homogenized. Profiling with a custom microarray (GPL22267) resulted in 1323 transcripts. After raw data were normalized (Smyth and Speed 2003; Ritchie et al. 2007), best linear unbiased estimates (BLUEs) and repeatabilities for transcript abundance were obtained separately for the Dent and Flint lines as described in Westhues et al. (2017). Passing a repeatability threshold set to 0.1 was required in both heterotic groups, resulting in 300 gene expression profiles for further analyses.

Transcriptomic sRNA data (S) were collected from all parent lines, of which 10 were replicated for calculation of repeatabilities. Four seeds per entry were taken from the same seed lot used for metabolite and mRNA profiling, and were grown at four different dates. At each date, seeds of all lines (with one seed per entry) were laid out in a completely randomized design, and grown under controlled conditions (25° 16 hr day, 21° 8 hr night, 70% air humidity) in a climate chamber. Seven days after sowing, for each entry, all four biological replicates were sampled as whole plants, pooled, and homogenized. Total RNA was isolated with the “mirVana miRNA isolation kit” (Ambion, Thermo Scientific). Illumina-compatible sequencing libraries were generated using the NEXTflex Small RNA Sequencing Kit v2 (BIOO SCIENTIFIC) and following the manufacturer’s recommendations with 1 µg of total RNA. Sequencing of 50-nt single end reads (SE50) was performed by the Beijing Genome Institute (BGI, Hong Kong, China) on an Illumina HiSeq 4000 sequencer. After adapter removal, the reads were filtered for 99.9% sequencing quality (i.e., Phred quality score of 30 for all nucleotides). Read counts were determined for sequences from 18 to 40 nt. Across all entries, read counts were quantile-normalized according to Bolstad and Irizarry (2003), with a modification that maintains zero read counts for sequences not present in the respective sample. To enable comparison of libraries with varying sequencing depths, quantile-normalized read counts were scaled to 1 million reads per library and all sRNAs with at least one read per million quantile-normalized reads in two entries were retained. Processing of S data were carried out using custom Java scripts and resulted in 477,193 unique sRNA sequences. After a quality check requiring expression in at least 10% of all samples, and a repeatability threshold set to 0.9, 10,736 sRNA expression levels remained for further analyses. The raw and processed sRNA expression data are deposited at NCBI GEO under the accession GSE106098.

Metabolomic data of roots (R)of all parent lines were quantified as described in de Abreu e Lima et al. (2017). In short, for each of the two replicates per line, 10 seedlings were grown in climate chambers. The roots were harvested 3.5 days after sowing, pooled, and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen to quench metabolic activity at sampling. Profiling resulted in 284 metabolites. After raw data were normalized (van den Berg et al. 2006), BLUEs and repeatabilities (w2) for metabolite levels were obtained as detailed in de Abreu e Lima et al. (2017) and Westhues et al. (2017). Passing a repeatability threshold set to 0.3 was required in both heterotic groups, resulting in 148 root metabolites for further analyses.

Principal component (PC) analysis of endophenotypes:

For predictors G, T, S, and R, individual variables were scaled and centered across both heterotic groups. For the observed two clusters, bivariate t-distributions were estimated with Maximum Likelihood, and their 0.95 quantiles were used to plot ellipses.

Statistical analysis of agronomic traits

Agronomic data of hybrids were analyzed in two stages, as outlined by Westhues et al. (2017). Briefly, adjusted entry means were determined for each environment, followed by a second stage of analysis, entailing the computation of BLUEs for all hybrids in HTot. For hybrids in the core set H, these BLUEs were used as response variables in the statistical models for predicting the hybrid performance. General combining ability (GCA) and specific combining ability (SCA) of parent lines, as well as variance components ( ) of all hybrids in HTot, were estimated as described by Westhues et al. (2017), in a random effects model with genomic relationship matrices for GCA and SCA effects using ASReml (Butler et al. 2009). The genomic relationship matrices for GCA effects of Dent and Flint parents, GD and GF, were determined as detailed below, and for SCA by multiplying the corresponding elements of GD and GF, as in Bernardo (1996). Heritabilities (H2) were computed on an entry-mean basis (Massman et al. 2013) as where was the residual error variance, and the harmonic mean of the number of test environments per hybrid.

Comparison of predictive abilities

A cross-validation (CV) scheme, stratified by the parent lines (Technow et al. 2014) and comprising 1000 runs, was applied to obtain unbiased estimates of the predictive ability, and to compare different predictor combinations, as detailed in Westhues et al. (2017). Briefly, 35 of 50 Dent and 29 of 41 Flint lines were sampled as training parents in each CV run. From all available hybrids between the 35 Dent and 29 Flint training parents, 200 were sampled at random as training hybrids. With this procedure, the 550 core set hybrids H were partitioned into 200 training set hybrids “TRN” and 350 test set hybrids “TST,” the latter comprising nT2 = 74 T2 hybrids (both parents tested in TRN), nT1d = 111 T1d hybrids (dent parent tested), nT1f = 117 T1f hybrids (flint parent tested), and nT0 = 48 T0 hybrids (neither parent tested in TRN) on average across all 1000 CV runs. For each hybrid fraction in a TST and for each scenario, defined as a single or combined predictor applied to a specific trait, predictive abilities were computed by using the same partitioning of TRN and TST samples. This resulted in s vectors pT2, pT1d, pT1f and pT0, respectively, containing the predictive abilities for 1000 CV runs, with s pertaining to the number of scenarios. This ensured that the vectors pT2, pT1d, pT1f and pT0, respectively, were comparable across all scenarios. Predictive abilities were obtained for each hybrid type, each scenario, and for each CV run by calculating Pearson correlations between predicted () and observed phenotypes (y).

Prediction models

Hybrid performance was predicted on the basis of the TRN hybrids in each CV run using predictor data (P, G, T, S, and R) that were available for the corresponding sets of parent lines D and F, respectively. A GCA model was used for predicting the performance of TST hybrids as described by Westhues et al. (2017). Correspondingly, WD and WF are matrices of feature measurements for the respective predictors (G, T, S, and R). The dimension of WD and WF, respectively, is determined by the number of parent lines in the corresponding heterotic group (lD = 50 and lF = 41) times the number of features in the corresponding predictor (mG = 37,392; mT = 300; mS = 10,736; and mR = 148). The columns in WD and WF were centered and standardized to unit variance. For each predictor and lines from each heterotic group, kernels were defined as

| (1) |

where m denotes the number of features for the respective predictor (VanRaden 2008), the transpose of WD, and the transpose of WF. In the case of P, coancestry coefficients were standardized for GD and GF, respectively. The model for GCA effects was as follows:

| (2) |

where y is the vector of observed hybrid performance (BLUEs), µ is the fixed model intercept, ZD is the design matrix for random GCA effects of the lines in D (gDc), and ZF is the design matrix for random GCA effects of the lines in F (gFc), referring to the c-th predictor data type. With this model, one predictor (C = 1) or multiple (C > 1) predictors can be considered simultaneously. The random effects (gDc and gFc) have expectation zero and covariance matrices equal to and for the GCA effects of the Dent and Flint lines, respectively, and for the residual error. For C > 1, gDc and gFc (c = 2…C) were assumed to be stochastically independent, and variance components for Dent and Flint were combined for each predictor, c, and stored as relative variance, vc, in each CV run for later analysis of the relative variances of the C predictors. By enhancing the model with SCA effects we arrived at the universal model for GCA and SCA effects described by Westhues et al. (2017).

In a modified approach, the model (Equation 2) was extended for predictor-specific weights wc:

| (3) |

where Kernels of C = 3 predictors (P, G, and T) were weighted and summed up, resulting in one joined weighted kernel per heterotic group. A grid search, varying the weights wP, wG, and wT in increments of 0.1, resulted in 66 different joined weighted kernels for Dent and Flint, respectively. For each of these 66 joined weighted kernels, the CV procedure was carried out using the same partitioning of TRN and TST samples as for all other analyses in this study. Consequently, for each weight combination, the median across 1000 predictive abilities was reported. In principle, this approach could be extended to include all five predictors, but computational demand becomes markedly higher with more dimensions.

All predictions were carried out in a computationally efficient manner by mixed model equations implemented in the R package “sommer” (Covarrubias-Pazaran 2016), providing BLUPs for hybrid performance.

Data availability

All statistical analyses, unless stated otherwise, were carried out using R (R Core Team 2016). The agronomic traits data of hybrids are available in the Supplemental Material, “agronomic.txt” in File S1. The pedigree and genomic data of the parent lines are available in the supplemental files “pedigree.txt” in File S1 and “genomic.txt” in File S1, respectively. The metabolic data of the parent lines can be downloaded as table S1 of de Abreu e Lima et al. (2017) at https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.13495. The transcriptomic data of the parent lines can be downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo with GEO accessions GPL22267 (for the mRNA data) and GSE106098 (for the sRNA data).

Results

Agronomic traits

Variance components of GCA effects were larger for Dent than for Flint parent lines, especially for GY (Table 1). The SCA effects for GY and GDMC contributed 8.5 and 7.1%, respectively, to the total genetic variance. Entry-mean heritabilities H2 of all hybrids were higher for GDMC (0.96) than for GY (0.91).

Table 1. GY and GDMC of the entire set HTot of 1567 hybrids, characterized by overall mean (µ), variance components of GCA effects for Dent () and Flint lines () and of SCA effects () as well as entry mean heritabilities (h2). Each is followed by its SE.

| Trait | µ | h2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GY (t/ha) | 11.60 | 0.72 ± 0.09 | 0.37 ± 0.06 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 0.91 ± 0.008 |

| GDMC (%) | 69.51 | 2.32 ± 0.31 | 2.03 ± 0.31 | 0.33 ± 0.03 | 0.96 ± 0.004 |

Population structure and kernel matrices

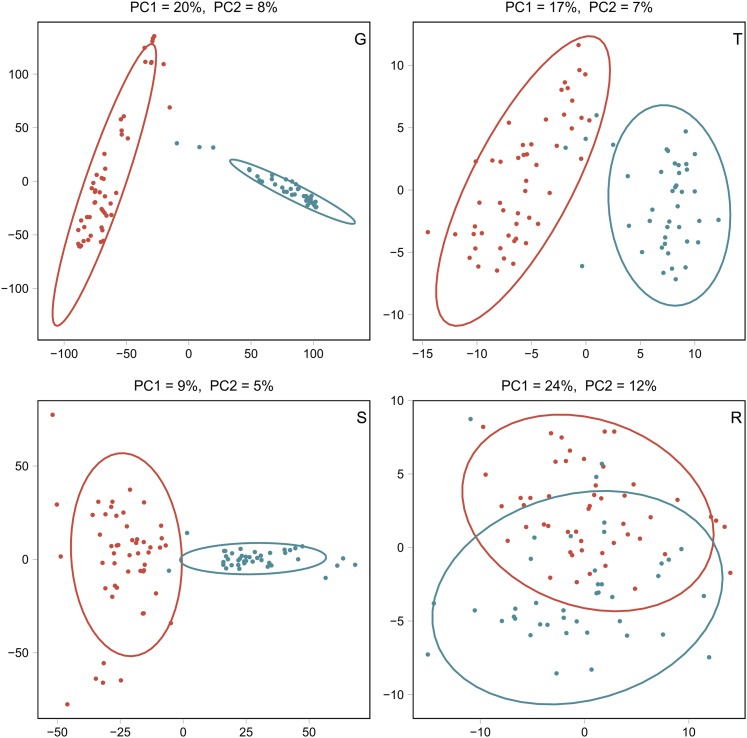

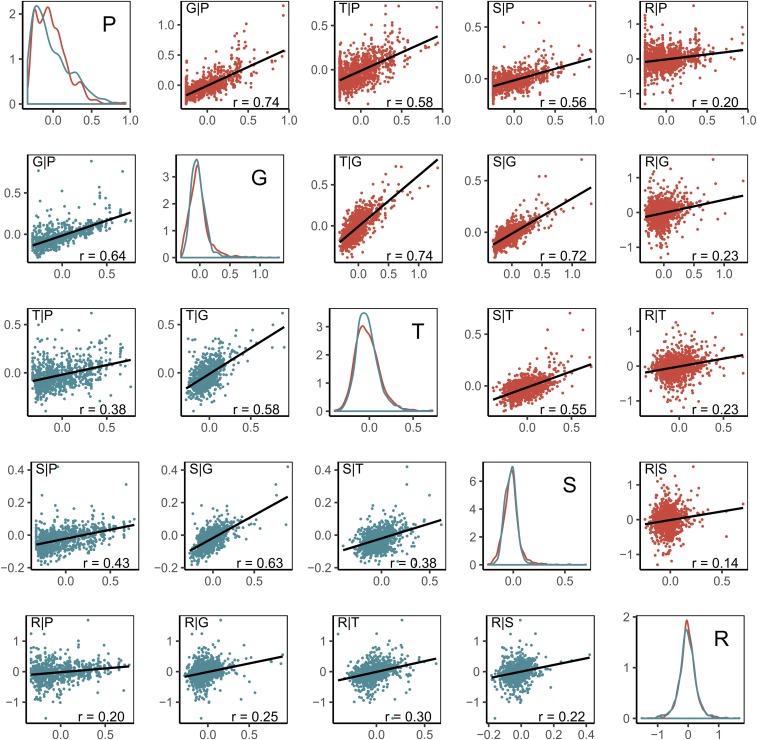

Dent and Flint lines were well separated for G, T, and S, and partially overlapped for R on the basis of the predictor data (Figure 1). Off-diagonal elements of the kernels GD and GF, respectively, exhibited strong associations (Figure 2) between G and each of P, T, or S, both for Dent (0.72 ≤ ≤ 0.74), and slightly lower for Flint (0.58 ≤ ≤ 0.64) lines. In contrast, associations between R and all remaining predictors were weak (0.14 ≤ ≤ 0.30). Remaining associations among P, T, and S were intermediate.

Figure 1.

PC analysis of Dent (red) and Flint lines (teal) for G, T, S, and R data. The variances explained by PC 1 (x-axis) and PC 2 (y-axis) are shown in the respective captions.

Figure 2.

Associations among off-diagonal elements of the kernel matrices for various predictors. Diagonal boxes: Densities of pairwise kernel coefficients among Dent (red) and among Flint (teal) parent lines. Off-diagonal boxes: Scatterplots of kernel coefficients for P, G, T, S, and R data with the Pearson correlation coefficients for pairwise comparisons between kernel matrices and labels defining the respective pair of predictors following the pattern “y-axis|x-axis.”

Single predictors

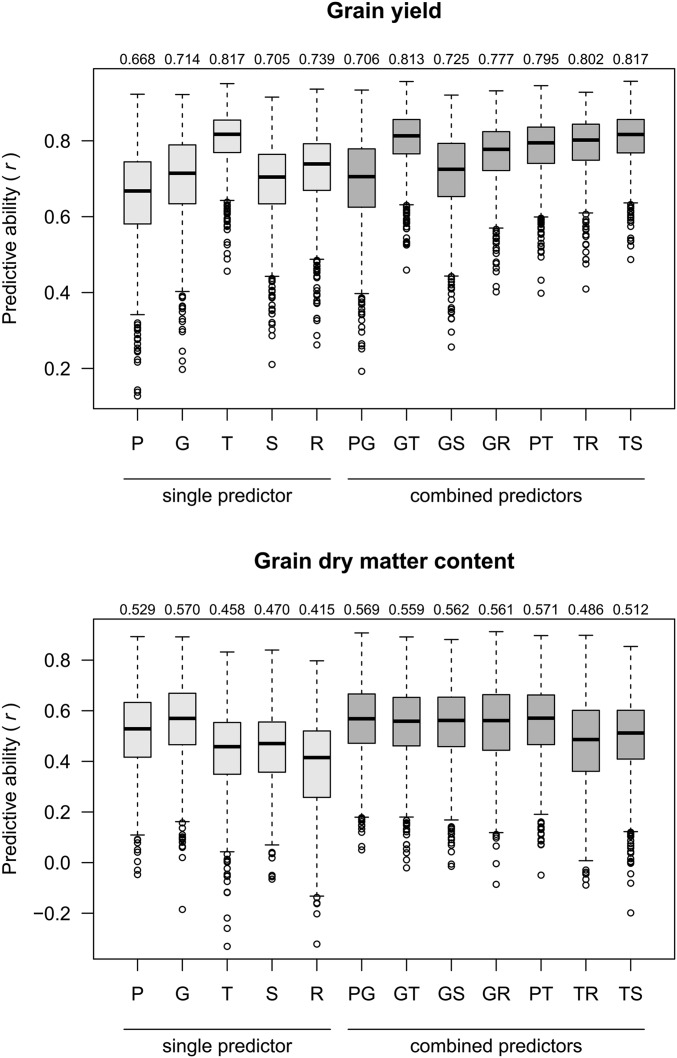

All of the following results refer to the prediction of T0 hybrids, unless stated otherwise. The median of predictive abilities from 1000 CV runs was obtained for each scenario where a single or combined predictor was applied to a specific trait. No predictor achieved consistently superior ranking for predictive ability (i.e., first or second highest among the five single predictors) for both traits simultaneously. The predictive ability for G was distinctly higher than for P and also higher than for S (Figure 3) for both traits. For GY, the predictor G was outperformed distinctly by T, and slightly by R, while, for GDMC, G was the best single predictor. Predictor T was always superior to R, and superior to S for GY, or nearly equal to it, for GDMC. The only single predictor that ranked relatively consistently across traits was S (Figure S1 in File S2); however, at a low level. Including SCA effects into our models did not improve predictive abilities (Table S1 in File S2) for genomic, transcriptomic, and metabolomic data, and did not change the ranking of predictors.

Figure 3.

Predictive abilities (r) for T0 hybrids of single predictors (P, G, T, S, and R) and combinations thereof for GY and GDMC from 1000 CV runs with median r given above each column.

Combining two predictors

Predictive abilities of the predictor combination PG were similar to those of G, and higher than for P (Figure 3 and Figure S2 in File S2). For GY, combining G with a second predictor other than P improved the predictive ability to a level superior to G alone, with the biggest improvement for GT, and, although less pronounced, for GR and GS. For GDMC, where G was the best single predictor, no improvement was observed. The best single predictor for GY was T, and combinations of T with any other predictor did not further improve predictive ability. The predictor combinations GT and PT performed consistently well across both traits (Figure S1 in File S2). Comparing pairs of single predictors with their combinations (Figure S2 in File S2) revealed that combinations comprising the best single predictor of the respective trait had similar or slightly lower predictive ability than the superior single component. Combinations of two predictors not comprising the best single predictor of the respective trait had higher predictive abilities than any of its components as single predictors. An exception was PG, where the combination was nearly identical to G alone.

Model combining three predictors P, G, and T

The three predictors P, G, and T were combined as independent factors (Equation 2) for the PGT model and provided median predictive abilities of 0.795 for GY and 0.573 for GDMC. The relative variances per predictor (combined for Dent and Flint) were vP = 0.20, vG = 0.21, and vT = 0.59 for GY, and vP = 0.31, vG = 0.42 and vT = 0.27 for GDMC, on average across all 1000 CV runs. When combining the three predictors by joined weighted kernels (Equation 3) in a grid search (Figure 4), the highest predictive abilities for GY (r = 0.822) were obtained with weights wP = 0.1, wG = 0.1, wT = 0.8 or wP = 0.0, wG = 0.2, wT = 0.8, and for GDMC (r = 0.599) with weights wP = 0.4, wG = 0.3, wT = 0.3, or wP = 0.3, wG = 0.4, wT = 0.3. The sensitivity of the predictive ability to varying weights (Figure S3 in File S2) matched well with the range of predictive abilities of the three contributing single predictors for GY. In contrast, for GDMC, the majority of the distribution exceeded the value of predictive ability of the superior single predictor G.

Figure 4.

Predictive abilities (r) for T0 hybrids in GY and GDMC, respectively, for 66 cases that differ in their weights for the predictors P, G, and T. Their corresponding kernels were joined with weights varying from 0 to 1 in increments of 0.1. Weights for P (wP) and G (wG) are shown at the respective scales; weights for T are wT = 1−wP−wG. Plotted values represent medians of r across 1000 CV runs. Heat color schemes differ for GY and GDMC, ranging from purple, indicating the respective lowest value, to yellow for the respective highest value.

Comparison of T0, T1, and T2

For GY, predictive abilities of T2, T1d, and T1f hybrids were on a similar level (Figure S4 in File S2), and were clearly separated from the lower values of T0 hybrids, however, with one exception: if T was included as a predictor, then predictive abilities for T0 hybrids were on a similarly high level as those for T1d, T1f, and T2 hybrids. For GDMC, predictive abilities were on clearly separated levels for T2 (high), T1d, as well as T1f (medium) and T0 (low) hybrids for all investigated single and combined predictors.

Discussion

In modern maize breeding programs, the DH and rapid SSD methods enable the production of thousands of parent lines and thus—hypothetically—millions of hybrids anew in each season. Similar progress is expected for other crops (Wedzony et al. 2009), especially with the cloning of the gene MATRILINEAL, which triggers haploid induction in maize (Kelliher et al. 2017). Testing all these potential hybrid candidates in multi-environment field trials is logistically and economically prohibitive. Any features that can be assessed on the parent lines in a high-throughput fashion at an early stage of plant development under standardized conditions, independent of season, and at acceptable costs, might prove useful to forecast the performance of hybrid candidates. In principle, this reduces the number of genotypes on which data have to be collected from n2 hybrids down to only 2n parent lines plus a moderately sized set of hybrids for training. Thus, breeding programs could become more efficient by producing and field testing only the most promising of the forecasted hybrid candidates.

Foundation of hybrid prediction

The careful establishment of genetically diverse heterotic groups is regarded as the foundation of hybrid breeding programs (Melchinger 1999). The breeding program at the University of Hohenheim, which generated the material used throughout this study, was based on these principles and comprises a heterotic pattern of Flint lines, predominantly based on landraces introduced to Europe centuries ago, and Dent lines, established from the Iowa Stiff Stalk Synthetic, and more recently introduced North American material (Stich et al. 2005; Fischer et al. 2008). Compared to Dent, the lower GCA variances in Flint corroborate the lower diversity of the long-established European Flint group, as observed in previous studies on grain maize hybrids from the same breeding program (Fischer et al. 2008; Schrag et al. 2010). Consistent with the breeding history, the PC analyses based on G, T, and S showed clearly separated heterotic groups (Figure 1).

Such clearly defined and separated heterotic groups result in decreased ratios of SCA variance to GCA variance, and, thereby, increase the efficiency of hybrid selection (Melchinger 1999; Reif et al. 2007). Accordingly, in our study, SCA variances were considerably smaller than GCA variances (Table 1), supporting estimates from previous studies in European grain maize (Fischer et al. 2008; Schrag et al. 2010; Technow et al. 2014) and silage maize (Argillier et al. 2000; Grieder et al. 2012; Westhues et al. 2017). These small SCA variances explain why incorporating SCA effects into the prediction models did not further improve predictive abilities (Table S1 in File S2), similar to what was observed by Westhues et al. (2017) in a related dataset for silage maize. In contrast, distinctly larger ratios of SCA to GCA variance were reported by Bernardo (1996) and Kadam et al. (2016), where the latter study comprised materials originating exclusively from several North American Dent heterotic groups. Heritabilites on an entry-mean basis corresponded well to estimates published by Massman et al. (2013), who reported 0.85 for GY and 0.98 for grain moisture among maize single-crosses.

Exploiting established predictors

Pedigree information was first used for progeny prediction (Bernardo 1994) because it was available at practically no cost and did not require sampling of any plant tissue. In our study, P was neither a superior predictor for GY nor for GDMC. While P surpassed the performance of all nongenomic predictors for GDMC, it performed most poorly for the more complex trait GY. This lack of predictive ability could be explained by the inability of P to account for anything but the expected relationship between two individuals. Conversely, the observed superiority of G over P for both investigated traits could be the result of direct estimation of the actual relationship between the inbred parent lines by the SNPs capturing both Mendelian sampling and the effects of selection (Cox et al. 1986; Speed and Balding 2015). In addition to realized relationship, genomic information also captures linkage disequilibrium (LD) between SNP markers and quantitative trait loci (QTL), thereby providing proxies for the relationship at the QTL (Schopp et al. 2017), but is very limited in addressing the activity of genes.

Capturing physiological epistasis

Other factors that influence the phenotype include the pervasive interactions between loci (Brem et al. 2005; Brown et al. 2014), especially for single-cross hybrids, in which all types of epistasis are fully used in selection (Cockerham 1961). Attempts to model such epistatic effects with genomic data by extending the model were largely unsuccessful (Hill et al. 2008; Guo et al. 2016) unless the training and test set shared close relatives (Jiang and Reif 2015). Given that genetic effects on the phenotype first pass through the intermediary transcriptome, proteome and metabolome (Ritchie et al. 2015), these biological strata—also called “endophenotypes” (Mackay et al. 2009)—offer the prospect of capturing and incorporating effects from the genome or any other upstream stratum including expression of genes or levels of gene products. The transcriptome, as the second biological stratum after the genome and reflecting its active part, is expected to incorporate gene expression and physiological epistasis (Sackton and Hartl 2016), going beyond mostly negligible statistical epistasis at the population level. Indeed, T was clearly the best single predictor for the more complex trait GY, supporting this hypothesis. Similar results with regard to genomic and mRNA data were published by Westhues et al. (2017), who tested the same factorial designs for silage maize traits in a subset of environments, and by Zenke-Philippi et al. (2017), who tested a smaller subset of the factorial designs for grain maize traits. The possibility of artificially high predictive abilities for T, due to a potential preselection bias of the custom mRNA chip, was ruled out by Westhues et al. (2017), who used the same T data. Additionally, independent studies also reported quite good performance of transcriptomic RNA-Seq data for the prediction of several yield-related traits in maize inbred lines (Guo et al. 2016), as well as for prediction of hybrid rice performance (Xu et al. 2016). Harnessing such advantages of transcriptomic data appears especially relevant in a hybrid breeding program if a very small fraction of candidates is selected from the huge number of possible hybrids, because the probability of successfully selecting the best hybrid candidates is a strongly convex function of predictive ability (Westhues et al. 2017). Accordingly, because the predictive ability of T for T0 hybrids in GY was 14% higher than for G, this would result in an approximately twofold higher success rate for selecting the top 100 hybrids out of 106 predicted candidates for seed production and intensive testing in field trials.

Exploring further transcriptomic predictors

Phenotypic buffering suggests that information on downstream “omics” predictors cannot necessarily be inferred from upstream predictors. For instance, increasing copy numbers of genes in yeast did not directly increase their expression levels, which may be an indicator for post-transcriptional regulation (Ishikawa et al. 2017). Micro-RNAs (miRNA), which are a subset of sRNAs, can repress the expression of genes by guiding RNA-induced silencing complexes (RISC) to their complementary mRNA (Mortimer et al. 2014). In addition to miRNAs, plants produce a wide variety of other sRNAs that regulate gene expression at the transcriptional level by directing epigenetic modifications of chromatin, likely equally contributing to phenotypic plasticity (Borges and Martienssen 2015). In our study, however, predictive abilities of S as a single predictor were weak, and, depending on the trait, similar or superior predictive abilities were achieved when using G or T (Figure S1 in File S2). Nonetheless, S never ranked last among all five predictors.

Given that the relative contributions of transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation determine the usefulness of mRNA levels to infer protein levels, the combination of mRNA with sRNA data might therefore suggest an intriguing alternative to capturing information similar to the further downstream proteome itself (Franks et al. 2017). Indeed, in our results for GY, predictive ability of TS was the highest among predictor combinations, but not superior to T as a single predictor (Figure 3). For GDMC, although the combination TS provided slightly higher predictive ability than T or S alone, no overall superiority was observed.

Approximating the phenotype

As the last biological stratum in the complex genotype-phenotype cascade, the metabolome is expected to capture and integrate all previous main effects and interactions within and among the various strata (Patti et al. 2012). For GY, predictive abilities based on R were higher than those achieved using G, albeit still lower than those obtained from using T. Hence, our results support previous findings on the potential of metabolites for predicting plant yields in studies on rice hybrids (Xu et al. 2016) and silage maize hybrids (Westhues et al. 2017). In contrast, for GDMC, predictive abilities of R were lowest, which is also in accordance with results from silage maize hybrids for dry matter content (Westhues et al. 2017).

It should be noted that in Westhues et al. (2017), as well as in our study, the metabolites were sampled from seedlings only a few days after sowing and grown in climate chambers. Less promising results have been reported for predictions based on leaf metabolites sampled from plants in the field ∼1 month after sowing (Westhues et al. 2017), highlighting the impact of environmental factors on metabolite profiles. More generally, the perturbation of feature levels in endophenotypes such as transcripts, metabolites, and proteins is considerably higher than for genomic sequence or marker data. Endophenotypes are responsive to nongenetic factors such as abiotic (Caldana et al. 2011; Waters et al. 2017) and biotic (Tzin et al. 2015) effects, and susceptible to varying sampling conditions, as applies especially to metabolites with extremely fast turnover rates (Arrivault et al. 2009). Additionally, age (Francesconi and Lehner 2014; Melé et al. 2015) and type of tissue (Melé et al. 2015; Searle et al. 2016) are impacting on the feature levels of endophenotypes.

Choice of sampling stage

Taken together, the previous points suggest that sampling of endophenotypes should ideally be carried out on plants grown in climate chambers under controlled conditions to reduce the impact of noise effects. With regard to the application of “omics”-based prediction in commercial hybrid breeding programs, sampling from seedlings cultivated in climate chambers provides additional advantages. Controlling the environmental conditions enables the standardization across batches. Therefore, independence from season allows to carry out the assessment throughout the entire year whenever new parent lines become available. Sampling of several tissues simultaneously (leaf, shoot, and root) is easier with seedlings than with fully developed plants in field plots. Another advantage is the shorter cultivation period, with which prediction results become more rapidly available to produce the predicted superior hybrids for further testing. Overall, sampling of the parent lines at an early stage of plant development under controlled and standardized conditions appears as an ideal basis to assess features in a high-throughput manner to forecast the performance of hybrid candidates in applied breeding programs.

Caveats of downstream predictors

While endophenotypes downstream of the genome may incorporate heritable upstream interactions within and among strata (Dalchau et al. 2011; Zhu et al. 2012), it must be considered that endophenotypes are responsive to nongenetic factors as discussed above. Technical limitations impose further potential constraints on the direct use of some endophenotypes. For example, even very recent metabolite-profiling technologies (Xu et al. 2016) capture only a small subset of the estimated total set of metabolites occurring in nature (Fernie 2007), and currently, it is still difficult to reliably quantify a large number of proteins (Franks et al. 2017). Moreover, measurement error is another source of noise, reducing the predictive power of endophenotypic features. Evaluations of predictive abilities, determined at various thresholds for required repeatability of individual T, S, or R features, suggested that intermediate thresholds provide highest predictive abilities, striking a balance between a minimum degree of repeatability on the one hand and a sufficient number of features on the other (Figure S5 in File S2). The optimum thresholds corresponded well between GY and GDMC, but differed among predictors, which may have multiple causes. First, the data sets of T, S, and R differed in their design, and, more specifically, in the number of replicated samples, which influences the impact of noise and also the precision of measurements. Second, the technologies for analyzing these endophenotypes differed, and are most likely associated with different levels of precision. Third, features of T, S, and R specifically interact with environmental and physiological factors while genomic sequence data remains unaffected by them. Fourth, the predictor data sets differed widely in their numbers of features, ranging from 284 for R to 477,193 for S in their initial data sets. Due to such differences among data sets of endophenotypes, the thresholds chosen for required feature repeatability were specific to each predictor.

Prediction of T2, T1, and T0 hybrids

The theoretical upper bound for predictive ability is given by (Bernardo 1996), which is in accordance with all observed predictive abilities for T0, T1, and T2 hybrids in both traits (Figure S4 in File S2). Further, the fraction of epistatic effects contributing to the covariance between hybrids, and captured by P or G, is expected to increase with the degree of relatedness among individuals (Westhues et al. 2017). It is therefore expected to be large for T2, intermediate for T1, and small for T0 hybrids. For GDMC, this corresponds to the observed high level of predictive abilities for T2 hybrids along with small differences among the corresponding predictors, the intermediate level of predictive abilities for T1 hybrids, and the low level of predictive abilities along with larger differences among predictors for T0 hybrids (Figure S4 in File S2). For GY, the predictive abilities for T2 hybrids also conform with these expectations. Moreover, the predictive abilities for T2 hybrids in GY were lower than in GDMC for all considered predictors (Figure S4 in File S2), which is in accordance with the lower heritability of GY compared to GDMC.

Interestingly, in GY, predictive abilities for T1 hybrids were nearly as high as those for T2 hybrids, and with only little variation among predictors. Similar observations were also obtained for T0 hybrids. Consequently, predictive abilities in T1 and T0 hybrids for GY were almost always greater than those for GDMC, which is inverse to the ratio observed for T2 hybrids. These unexpected results may be related to the capability of predictors capturing epistasis and warrant further research.

Usefulness of predictors across traits

From an economic perspective, a single predictor with good predictive ability for multiple traits would be highly desirable. While T and R exhibited highest predictive abilities for GY, they were lowest for GDMC. And whereas G and P were superior predictors for GDMC, they performed relatively poorly for GY (Figure 3 and Figure S1 in File S2). Such strong interactions between trait and predictor were also observed in studies on hybrids for silage maize traits (Westhues et al. 2017), and on inbred lines for grain maize traits (Guo et al. 2016), which indicates that for prediction with “omics”-derived kernels, the merit of an “omics” data type strongly depends on the trait under investigation. In practice, knowledge on the suitability of available predictors for a given trait could be derived either from previous studies or from CV applied to all available data, i.e., the training data set. Alternatively, multiple predictors could be combined in one model, aiming to provide consistently high predictive ability across traits by complementing favorable properties of different predictors.

Combining different predictor types

By comparing pairs of single predictors with their combinations (Figure S2 in File S2), we can draw two conclusions. First, combining the best single predictor for a certain trait with another predictor did not improve predictions, and, in some cases, rather impaired predictive ability. Second, combinations that did not comprise the best single predictor tended to be superior to both components individually.

The two above-mentioned conclusions provide insights into whether genomic prediction (i.e., G only) could be improved by combining G with other “omics” predictors. Based on the first conclusion, and, in line with all observations, for GDMC no improvement would be expected for combinations of G with another predictor. Based on the second conclusion, for GY, combinations of G with another predictor would be expected to improve predictive abilities. This was consistent with all observations, except for GP, indicating that there is no complementary effect of P beyond G. However, absence or presence of complementary effects could not be connected to the observed degrees of association between the kernel coefficients for the respective predictors (Figure 2).

The consistently good performance of GT across both traits may be explained by the fact that it combines the best single predictor for GY (T) and for GDMC (G). Further, the relatively good performance of PT in GY may be due to the contribution of T as the best single predictor for GY. Although neither P nor T were the best single predictor for GDMC, this combination also performed well for GDMC, which may be explained by the high association between P and G for their kernel coefficients (Figure 2), and by the observation that P is the second ranked single predictor for GDMC after G. In addition, T seems to capture a fraction of the information in G that is complementary to P so that the combination PT performed comparably to the best single predictor G and even slightly better than GT for GDMC. These combinations—GT and PT—provided some advantages for prediction, not only in this study on yield-related traits in grain maize, but also for several yield and quality-related traits in silage maize (Westhues et al. 2017).

Finally, we studied the triple combination PGT, because P could be considered a generally available source of information, and G and T were the best single predictors for the two traits under investigation. Predictive abilities of PGT, when compared to the related two-predictor combinations GT and PT, were lower for GY, but higher for GDMC. To arrive at clear recommendations for the predictors P, G, and T, we further investigated their relevance using three approaches: (1) ranking of single predictors with respect to predictive abilities, (2) examining relative variance components from a model comprising all three predictors as independent factors, and (3) determining weights by a grid search on joined weighted kernels. For GY, all three approaches clearly indicated that T had a high impact for predicting hybrid performance, while G followed by P had lower impact. For GDMC, the order of impact was G, P, and T, albeit differences among these predictors were less pronounced than for GY.

Application in breeding programs

Despite the shown benefits of using transcriptomic data for hybrid prediction, the currently higher sampling costs of endophenotypes compared to genomic data should not be neglected. One strategy to balance costs and benefits could be a selective “omics”-screening strategy, where transcriptomic measurements are only taken on a subset of genotypes. For all other genotypes, which have pedigree and genomic records, transcriptomic values could possibly be imputed (Gamazon et al. 2015), thereby boosting predictive ability while limiting expenses. Further open points are whether parent lines should first be selected based on their per se performance before carrying out molecular analyses, and to which degree the production and field evaluation of testcrosses is still required when applying “omics”-based prediction methods. Ultimately, these operational and economic aspects need to be considered well for successful application in applied breeding programs and warrant further research.

Conclusions

We have shown that the excellence of a predictor is highly trait-dependent. The respective best single predictor was always comparable or superior to any combination of predictors, highlighting the sufficiency of a single predictor for the prediction of one trait. Due to the interaction between trait and predictor, the prediction of multiple traits can benefit from the complementation of predictors if the best single predictor for any trait is unavailable. Given that P, and often also G, are available in hybrid breeding programs, their combination with T seems to provide a robust basis for prediction of a broad spectrum of traits. Based on the crucial role of mRNA for the genotype-phenotype cascade, we speculate that combining T with G or P enables superior predictive abilities, warranting further research on using mRNA for maize hybrid prediction.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental material is available online at www.genetics.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1534/genetics.117.300374/-/DC1.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the Agricultural Experimental Research station, University of Hohenheim, for excellent technical assistance in conducting the field experiments, H. P. Piepho and H. F. Utz for their advice on the statistical analyses, as well as T. Würschum, W. Molenaar, and two anonymous reviewers for valuable suggestions to improve the content of the manuscript. We are indebted to the group of R. Fries from Technische Universität München for the SNP genotyping of the parent inbred lines, and to A. Schlereth, M. Stitt, Z. Nikoloski, and L. Willmitzer of the Max-Planck Institute of Molecular Plant Physiology, Potsdam, Germany, who designed and conducted the metabolic experiments, published in previous publications (de Abreu e Lima et al. 2017; Westhues et al. 2017). Further, we acknowledge the computational support by the state of Baden-Württemberg through bwHPC. This project was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) within the projects OPTIMAL (FKZ: 0315958B, 0315958F) and SYNBREED (FKZ: 0315528D), and by the German Research Foundation (DFG, Grants No. ME 2260/5-1 and SCHO 764/6-1). Financial support for M.W. was provided by the Fiat Panis Foundation, Ulm, Germany.

Author contributions: W.S. and A.E.M. developed the lines and hybrids, W.S. and A.E.M. designed the field experiments, T.A.S. analyzed the agronomic, pedigree, and genomic data, S.S. designed the transcriptomic experiments, F.S. and A.T. conducted the transcriptomic experiments, M.W. analyzed the metabolic and transcriptomic data, T.A.S., M.W., and A.E.M. devised the prediction models, T.A.S. and M.W. implemented the prediction models and developed software. T.A.S., M.W., and A.E.M. wrote the manuscript.

Footnotes

Communicating editor: A. Charcosset

Literature Cited

- Argillier O., Mechin V., Barrière Y., 2000. Inbred line evaluation and breeding for digestibility-related traits in forage maize. Crop Sci. 40: 1596–1600. [Google Scholar]

- Arrivault S., Guenther M., Ivakov A., Feil R., Vosloh D., et al. , 2009. Use of reverse-phase liquid chromatography, linked to tandem mass spectrometry, to profile the Calvin cycle and other metabolic intermediates in Arabidopsis rosettes at different carbon dioxide concentrations. Plant J. 59: 824–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardo R., 1994. Prediction of maize single-cross performance using RFLPs and information from related hybrids. Crop Sci. 34: 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardo R., 1996. Best linear unbiased prediction of maize single-cross performance. Crop Sci. 36: 50–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolstad B. M., Irizarry R. A., 2003. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics 19: 185–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges F., Martienssen R. A., 2015. The expanding world of small RNAs in plants. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 16: 727–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brem R. B., Storey J. D., Whittle J., Kruglyak L., 2005. Genetic interactions between polymorphisms that affect gene expression in yeast. Nature 436: 701–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown A. A., Buil A., Vinuela A., Lappalainen T., Zheng H. F., et al. , 2014. Genetic interactions affecting human gene expression identified by variance association mapping. eLife 3: e01381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning B. L., Browning S. R., 2009. A unified approach to genotype imputation and haplotype-phase inference for large data sets of trios and unrelated individuals. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 84: 210–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler D. G., Cullis B. R., Gilmour A. R., Gogel B. J., 2009. Mixed Models for S Language Environments: ASReml-R Reference Manual. Training Series QE02001. Queensland Department of Primary Industries and Fisheries, NSW Department of Primary Industries, Brisbane. [Google Scholar]

- Caldana C., Degenkolbe T., Cuadros-Inostroza A., Klie S., Sulpice R., et al. , 2011. High-density kinetic analysis of the metabolomic and transcriptomic response of Arabidopsis to eight environmental conditions. Plant J. 67: 869–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockerham C. C., 1961. Implications of genetic variances in a hybrid breeding program. Crop Sci. 1: 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Covarrubias-Pazaran G., 2016. Genome-assisted prediction of quantitative traits using the R package sommer. PLoS One 11: e0156744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox T. S., Murphy J. P., Rodgers D. M., 1986. Changes in genetic diversity in the red winter wheat regions of the United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83: 5583–5586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalchau N., Baek S. J., Briggs H. M., Robertson F. C., Dodd A. N., et al. , 2011. The circadian oscillator gene GIGANTEA mediates a long-term response of the Arabidopsis thaliana circadian clock to sucrose. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108: 5104–5109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Abreu e Lima F., Westhues M., Cuadros-Inostroza A., Willmitzer L., Melchinger A. E., et al. , 2017. Metabolic robustness in young roots underpins a predictive model of maize hybrid performance in the field. Plant J. 90: 319–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvick D. N., 1999. Heterosis: feeding people and protecting natural resources, pp. 19–29 in The Genetics and Exploitation of Heterosis in Crops, edited by Coors J. G., Pandey S. ASA-CSSA, Madison, WI. [Google Scholar]

- Falconer D. S., Mackay T. F., 1996. Introduction to Quantitative Genetics. Longman Group, Essex, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Fernie A. R., 2007. The future of metabolic phytochemistry: larger numbers of metabolites, higher resolution, greater understanding. Phytochemistry 68: 2861–2880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer S., Möhring J., Schön C.-C., Piepho H.-P., Klein D., et al. , 2008. Trends in genetic variance components during 30 years of hybrid maize breeding at the University of Hohenheim. Plant Breed. 127: 446–451. [Google Scholar]

- Francesconi M., Lehner B., 2014. The effects of genetic variation on gene expression dynamics during development. Nature 505: 208–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks A., Airoldi E., Slavov N., 2017. Post-transcriptional regulation across human tissues. PLoS Comput. Biol. 13: e1005535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamazon E. R., Wheeler H. E., Shah K. P., Mozaffari S. V., Aquino-Michaels K., et al. , 2015. A gene-based association method for mapping traits using reference transcriptome data. Nat. Genet. 47: 1091–1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganal M. W., Durstewitz G., Polley A., Bérard A., Buckler E. S., et al. , 2011. A large maize (Zea mays L.) SNP genotyping array: development and germplasm genotyping, and genetic mapping to compare with the B73 reference genome. PLoS One 6: e28334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieder C., Dhillon B. S., Schipprack W., Melchinger A. E., 2012. Breeding maize as biogas substrate in Central Europe: II. Quantitative-genetic parameters for inbred lines and correlations with testcross performance. Theor. Appl. Genet. 124: 981–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z., Magwire M. M., Basten C. J., Xu Z., Wang D., 2016. Evaluation of the utility of gene expression and metabolic information for genomic prediction in maize. Theor. Appl. Genet. 129: 2413–2427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habier D., Fernando R. L., Kizilkaya K., Garrick D. J., 2011. Extension of the Bayesian alphabet for genomic selection. BMC Bioinformatics 12: 186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson C. R., 1984. Applications of Linear Models in Animal Breeding. University of Guelph, Guelph, ON. [Google Scholar]

- Hill W. G., Goddard M. E., Visscher P. M., 2008. Data and theory point to mainly additive genetic variance for complex traits. PLoS Genet. 4: e1000008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa K., Makanae K., Iwasaki S., Ingolia N. T., Moriya H., 2017. Post-translational dosage compensation buffers genetic perturbations to stoichiometry of protein complexes. PLoS Genet. 13: e1006554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Reif J. C., 2015. Modeling epistasis in genomic selection. Genetics 201: 759–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadam D., Potts S., Bohn M. O., Lipka A. E., Lorenz A., 2016. Genomic prediction of hybrid combinations in the early stages of a maize hybrid breeding pipeline. G3 6: 3443–3453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelliher T., Starr D., Richbourg L., Chintamanani S., Delzer B., et al. , 2017. MATRILINEAL, a sperm-specific phospholipase, triggers maize haploid induction. Nature 542: 105–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lappalainen T., Sammeth M., Friedländer M. R., ’t Hoen P. A., Monlong J., et al. , 2013. Transcriptome and genome sequencing uncovers functional variation in humans. Nature 501: 506–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Castillo-González C., Yu B., Zhang X., 2017. The functions of plant small RNAs in development and in stress responses. Plant J. 90: 654–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay T. F. C., Stone E. A., Ayroles J. F., 2009. The genetics of quantitative traits: challenges and prospects. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10: 565–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maenhout S., De Baets B., Haesaert G., 2010. Graph-based data selection for the construction of genomic prediction models. Genetics 185: 1463–1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massman J. M., Gordillo G. A., Lorenzana R. E., Bernardo R., 2013. Genomewide predictions from maize single-cross data. Theor. Appl. Genet. 126: 13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melchinger A. E., 1999. Genetic diversity and heterosis, pp. 99–118 in The Genetics and Exploitation of Heterosis in Crops, edited by Coors J. G., Pandey S. ASA-CSSA, Madison, WI. [Google Scholar]

- Melchinger A. E., Gumber R. K., 1998. Overview of heterosis and heterotic groups in agronomic crops, pp. 29–44 in Concepts and Breedings of Heterosis in Crop Plants, CSSA Special Publication no. 25, edited by Lamkey K. R., Staub J. E. Crop Science Society of America, Madison, WI. [Google Scholar]

- Melé M., Ferreira P. G., Reverter F., DeLuca D. S., Monlong J., et al. , 2015. The human transcriptome across tissues and individuals. Science 348: 660–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meuwissen T. H. E., Hayes B. J., Goddard M. E., 2001. Prediction of total genetic value using genome-wide dense marker maps. Genetics 157: 1819–1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer S. A., Kidwell M. A., Doudna J. A., 2014. Insights into RNA structure and function from genome-wide studies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 15: 469–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson H. D., Williams E. R., 1976. A new class of resolvable incomplete block designs. Biometrika 63: 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Patti G. J., Yanes O., Siuzdak G., 2012. Metabolomics: the apogee of the omics trilogy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13: 263–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team , 2016. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna: Available at: https://www.R-project.org. Accessed: October 9, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Reif J. C., Gumpert F. M., Fischer S., Melchinger A. E., 2007. Impact of interpopulation divergence on additive and dominance variance in hybrid populations. Genetics 176: 1931–1934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedelsheimer C., Czedik-Eysenberg A., Grieder C., Lisec J., Technow F., et al. , 2012. Genomic and metabolic prediction of complex heterotic traits in hybrid maize. Nat. Genet. 44: 217–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie M. D., Holzinger E. R., Li R., Pendergrass S. A., Kim D., 2015. Methods of integrating data to uncover genotype–phenotype interactions. Nat. Rev. Genet. 16: 85–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie M. E., Silver J., Oshlack A., Holmes M., Diyagama D., et al. , 2007. A comparison of background correction methods for two-colour microarrays. Bioinformatics 23: 2700–2707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackton T. B., Hartl D. L., 2016. Perspective genotypic context and epistasis in individuals and populations. Cell 166: 279–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schopp P., Müller D., Melchinger A. E., 2017. Accuracy of genomic prediction in synthetic populations depending on the number of parents, relatedness and ancestral linkage disequilibrium. Genetics 205: 441–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrag T. A., Möhring J., Melchinger A. E., Kusterer B., Dhillon B. S., et al. , 2010. Prediction of hybrid performance in maize using molecular markers and joint analyses of hybrids and parental inbreds. Theor. Appl. Genet. 120: 451–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searle B. C., Gittelman R. M., Manor O., Akey J. M., 2016. Detecting sources of transcriptional heterogeneity in large-scale RNA-seq data sets. Genetics 204: 1391–1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth G. K., Speed T., 2003. Normalization of cDNA microarray data. Methods 31: 265–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speed D., Balding D. J., 2015. Relatedness in the post-genomic era: is it still useful? Nat. Rev. Genet. 16: 33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stich B., Melchinger A. E., Frisch M., Maurer H. P., Heckenberger M., et al. , 2005. Linkage disequilibrium in European elite maize germplasm investigated with SSRs. Theor. Appl. Genet. 111: 723–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Technow F., Schrag T. A., Schipprack W., Bauer E., Simianer H., et al. , 2014. Genome properties and prospects of genomic prediction of hybrid performance in a breeding program of maize. Genetics 197: 1343–1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzin V., Fernandez-Pozo N., Richter A., Schmelz E. A., Schoettner M., et al. , 2015. Dynamic maize responses to aphid feeding are revealed by a time series of transcriptomic and metabolomic assays. Plant Physiol. 169: 1727–1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg R. A., Hoefsloot H. C. J., Westerhuis J. A., Smilde A. K., Van der Werf M. J., 2006. Centering, scaling, and transformations: improving the biological information content of metabolomics data. BMC Genomics 7: 142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanRaden P. M., 2008. Efficient methods to compute genomic predictions. J. Dairy Sci. 91: 4414–4423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters A. J., Makarevitch I., Noshay J., Burghardt L. T., Hirsch C. N., et al. , 2017. Natural variation for gene expression responses to abiotic stress in maize. Plant J. 89: 706–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedzony M., Forster B., Zur I., Golemiec E., Szechynska-Hebda M., et al. , 2009. Progress in doubled haploid technology in higher plants, pp. 1–33 in Advances in Haploid Production in Higher Plants, edited by Touraev A., Forster B. P., Jain S. M. Springer, Berlin. [Google Scholar]

- Westhues M., Schrag T. A., Heuer C., Thaller G., Utz H. F., et al. , 2017. Omics-based hybrid prediction in maize. Theor. Appl. Genet. 130: 1927–1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S., Xu Y., Gong L., Zhang Q., 2016. Metabolomic prediction of yield in hybrid rice. Plant J. 88: 219–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenke-Philippi C., Frisch M., Thiemann A., Seifert F., Schrag T. A., et al. , 2017. Transcriptome-based prediction of hybrid performance with unbalanced data from a maize breeding programme. Plant Breed. 136: 331–337. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J., Sova P., Xu Q., Dombek K. M., Xu E. Y., et al. , 2012. Stitching together multiple data dimensions reveals interacting metabolomic and transcriptomic networks that modulate cell regulation. PLoS Biol. 10: e1001301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All statistical analyses, unless stated otherwise, were carried out using R (R Core Team 2016). The agronomic traits data of hybrids are available in the Supplemental Material, “agronomic.txt” in File S1. The pedigree and genomic data of the parent lines are available in the supplemental files “pedigree.txt” in File S1 and “genomic.txt” in File S1, respectively. The metabolic data of the parent lines can be downloaded as table S1 of de Abreu e Lima et al. (2017) at https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.13495. The transcriptomic data of the parent lines can be downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo with GEO accessions GPL22267 (for the mRNA data) and GSE106098 (for the sRNA data).