Abstract

Background

A significant proportion of donation after circulatory death (DCD) kidneys are declined for transplantation because of concerns over their quality. Ex vivo normothermic machine perfusion (NMP) provides a unique opportunity to assess the quality of a kidney and determine its suitability for transplantation.

Methods

In phase 1 of this study, declined human DCD kidneys underwent NMP assessment for 60 min. Kidneys were graded 1–5 using a quality assessment score (QAS) based on macroscopic perfusion, renal blood flow and urine output during NMP. In phase 2 of the study, declined DCD kidneys were assessed by NMP with an intention to transplant them.

Results

In phase 1, 18 of 42 DCD kidneys were declined owing to poor in situ perfusion. After NMP, 28 kidneys had a QAS of 1–3, and were considered suitable for transplantation. In phase 2, ten of 55 declined DCD kidneys underwent assessment by NMP. Eight kidneys had been declined because of poor in situ flushing in the donor and five of these were transplanted successfully. Four of the five kidneys had initial graft function.

Conclusion

NMP technology can be used to increase the number of DCD kidney transplants by assessing their quality before transplantation.

Short abstract

Increases available kidneys

Introduction

Over the past decade the proportion of donation after circulatory death (DCD) kidneys used in transplantation has increased significantly1. Although this is a welcome trend, DCD kidneys are associated with an increased risk of delayed graft function and sometimes suboptimal renal function2, 3. Up to 15 per cent of these kidneys that are retrieved are subsequently declined for transplantation4. Kidneys are declined for many reasons but the decision always has an element of subjectivity. It is possible that a significant number of transplantable kidneys are incorrectly deemed unsuitable.

Normothermic machine perfusion (NMP) is a novel organ preservation system designed using cardiopulmonary bypass technology. A warmed, oxygenated, non‐inflammatory red cell‐based solution is pumped through the kidney in an organ chamber5, 6. This allows ex vivo restoration of function, and provides a unique opportunity to assess the quality of a kidney objectively and to inform the decision whether to transplant.

The aim of this study was to develop NMP as a technology to assess and then transplant DCD kidneys that had been deemed unsuitable for transplantation. The study had two phases. In phase 1, declined DCD kidneys were assessed by NMP to determine what proportion might be suitable for transplantation. This was an assessment phase only, with no intention to proceed to transplantation. In phase 2, DCD kidneys that were deemed unsuitable for transplantation were assessed by NMP with the aim of transplanting kidneys that met defined assessment parameters.

Methods

In phase 1, from December 2012 to June 2014, DCD kidneys from the national organ allocation scheme that were declined for transplantation were recruited into this research project. Ethical approval was granted by the national ethical approval committee in the UK (12/EM/0143).

In phase 2, from November 2015 to February 2017, after agreement from National Health Service Blood and Transplant (NHSBT), kidneys offered through the National Kidney Allocation Fast‐track Scheme that were subsequently declined for transplantation by all UK transplant centres were recruited into the study.

In both phases, consent for recruitment of the kidney into the study was obtained from the donor family by specialist nurses in organ donation. Ethical approval to transplant kidneys that had been deemed unsuitable was granted by the national ethical approval committee in the UK (15/EE/0175).

The following inclusion criteria were applied: kidneys declined for transplantation because of adverse donor characteristics; poor in situ perfusion in the donor; prolonged ischaemia; adverse gross appearance; histological evidence of chronic damage; and adverse cold perfusion parameters. In addition, donors and recipients had to be at least 18 years old, and recipients were undergoing a first or second renal transplant from a deceased donor. Kidneys were not recruited if deemed unsuitable for transplantation based on contraindications defined by current NHSBT criteria7, if they had irreparable vascular damage, or if the recipient was having a third or subsequent transplant.

A suitable recipient was identified and, on arrival of the kidney at the transplant centre, it underwent a period of NMP under aseptic conditions in the operating theatre. If the kidney was deemed suitable for transplantation, the recipient was prepared for the transplant procedure in the usual way.

Normothermic machine perfusion

Kidneys were prepared for transplantation and perfusion. The renal artery was cannulated, or where possible a patch cannula was attached to the Carrel aortic patch for connection to the circuit. The renal vein and ureter were also cannulated. Kidneys were perfused with an oxygenated red blood cell‐based solution mixed with a priming solution for 60 min at 35·0–36·0 °C. Supplements were infused to replace urine output and maintain a physiological environment5, 6. After perfusion, kidneys were flushed with 1 litre of hyperosmolar citrate solution (Soltran®; Baxter Healthcare, Thetford, UK) and placed on ice until transplanted.

Quality assessment parameters

During NMP, renal blood flow was monitored continuously and recorded every 5 min, and the total urine output measured. Blood gas analysis of arterial and venous blood was used to record acid–base homeostasis and measure oxygen consumption.

Blood samples were taken before perfusion and after 60 min of NMP. A urine sample was also taken after 60 min.

The NMP quality assessment score (QAS) was derived as a composite of three factors8: macroscopic appearance, mean renal blood flow and total urine output. Kidneys with a QAS score of 3 or less were considered suitable for transplantation provided there were no other preclusions to transplant8. The oxygen consumption was calculated at the end of NMP using arterial and venous blood gas samples, as (arterial P o 2 – venous P o 2) × renal blood flow/weight, where P o 2 is the partial pressure of oxygen.

A sample of urine was taken from the kidney after 60 min of NMP to measure levels of neutrophil gelatinase‐associated lipocalin (NGAL) using a human NGAL sandwich enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay kit (Cohesion Biosciences, London, UK). The samples were centrifuged at 516 g at 4 °C for 10 min, then stored at –70 °C until analysis.

Histopathological assessment

The Remuzzi score9 was calculated by a consultant pathologist for all kidneys in phase 1 and where necessary in phase 2. Haematoxylin and eosin‐stained 4‐μm sections cut from wedge biopsies taken at the end of cold storage were used. Kidney sections were also assessed for the degree of acute tubular injury, which was graded as mild, mild to moderate, moderate or severe.

Transplantation

Kidneys were transplanted into the right iliac fossa, with anastomosis of the artery and vein to the external iliac vessels, and the ureter to the bladder as an extravesical onlay over a double J stent.

Immunosuppression

All patients were immunosuppressed with a standard regimen of basiliximab (20 mg on days 0 and 4), tacrolimus (0·1 mg per kg per day to maintain trough levels of 6–10 ng/ml), mycophenolate mofetil (500 mg twice daily) and prednisolone (20 mg daily).

Statistical analysis

Donor information recorded included: age, sex, ethnicity, cause of death, Kidney Donor Risk Index (KDRI)10, past medical history, BMI and serum creatinine level. Surgical parameters were also recorded, including: warm ischaemia time, cold ischaemia time, preservation solution used, and the quality of cold perfusion flush on the back bench as scored subjectively by retrieving surgeons.

Continuous data are presented as mean(s.d.) and median (range), as appropriate. Data were analysed using t test or Mann–Whitney U test. P < 0·050 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Phase 1

A total of 42 DCD kidneys were included in the phase 1 cohort. The majority were declined because of poor in situ perfusion (18) (Table 1). Other reasons were: malignancy (2), technical factors (5), long cold ischaemia time (8), poor hypothermic machine perfusion parameters (4) or specific donor characteristics (5). Donor age ranged from 26 to 79 years. Most donors were white; two kidneys were from black donors and two from Asian donors. The majority were men (29 of 42). The mean(s.d.) warm ischaemia time was 14(4) min and the mean cold ischaemia time before commencing NMP was 27·0(9·6) h. The mean terminal creatinine level was 114(73) μmol/l. The median KDRI was 1·80 (range 0·80–2·67).

Table 1.

Donor and surgical demographics for phase 1

| Reason for decline | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inadequate in situ perfusion (n = 18) | Malignancy (n = 2) | Technical factor/ injury (n = 5) | Long CIT (n = 8) | HMP parameters (n = 4) | Past medical history (n = 5) | |

| Age (years)* | 54(16) | 67(4) | 63(7) | 73(6) | 66(5) | 46(19) |

| Sex ratio (M : F) | 14 : 4 | 0 : 2 | 2 : 3 | 5 : 3 | 3 : 1 | 5 : 0 |

| BMI (kg/m2)* | 25·7(4·6) | 34·7(13·1) | 30·6(14·5) | 26·0(3·7) | 30·4(10·2) | 24·2(0·6) |

| KDRI† | 1·32 | 1·97 | 1·40 | 2·57 | 1·73 | 1·05 |

| (0·80–2·17) | (1·96–1·97) | (1·27–1·51) | (1·72–2·67) | (1·56–1·86) | (0·82–2·03) | |

| Cause of death | ||||||

| Intracranial haemorrhage | 11 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Pulmonary disease | 4 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Congestive cardiac failure | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypoxic brain injury | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Cardiac arrest | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Myocardial infarct | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Creatinine before retrieval (µmol/l)* | 89(36) | 203(152) | 81(61) | 118(21) | 133(111) | 293(166) |

| WIT (min)* | 12(2) | 14(1) | 12(7) | 14(4) | 16(2) | 12(2) |

| CIT (h)* | 24·2(15·9) | 23·4(15·7) | 31·2(5·4) | 23·2(10·5) | 28·4(10·7) | 25·5(3·2) |

Values are

mean(s.d.) and

median (range). CIT, cold ischaemia time; HMP, hypothermic machine perfusion; KDRI, Kidney Donor Risk Index; WIT, warm ischaemia time.

The majority of QAS scores in phase 1 kidneys were between 1 and 3 (28 of 42), and these kidneys were therefore considered suitable for transplantation. Table 2 shows the association between the reason for decline and the NMP QAS. Most kidneys declined owing to inadequate in situ perfusion had a favourable QAS. Those kidneys declined because of a long cold ischaemia time (at the time of offer) did not perform well during NMP, with five of eight receiving a score of 4 or 5, meaning they were unsuitable for transplantation. The kidneys declined owing to poor hypothermic machine perfusion parameters also did not perform well during 1 h of NMP perfusion, with two of the four receiving an unfavourable QAS.

Table 2.

Reason for decline and normothermic perfusion quality assessment score in phase 1

| Quality assessment score | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1–3 | 4–5 | |

| Inadequate perfusion | 14 | 4 |

| Malignancy | 2 | 0 |

| Technical/anatomical | 5 | 0 |

| Long CIT | 3 | 5 |

| HMP parameters | 2 | 2 |

| Past medical history | 2 | 3 |

| Total | 28 | 14 |

CIT, cold ischaemia time; HMP, hypothermic machine perfusion.

Phase 2

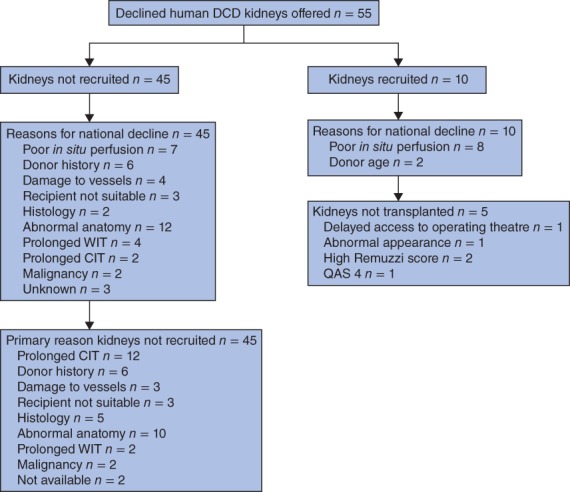

Fifty‐five kidneys from 37 DCD donors were offered for research (Fig. 1). Ten kidneys from six donors were recruited into the study; the remaining 45 were not recruited. The reasons why all UK units initially declined the 45 DCD kidneys are listed in Fig. 1. At the time of being offered for this research project, further information was sometimes unavailable and the cold storage interval had been lengthened because of the logistics of the offering scheme. Prolonged cold ischaemia time became the final reason for not recruiting 12 kidneys (22 per cent) into the study.

Figure 1.

Phase 2 study: flow diagram listing the number of offers, kidneys not recruited, reasons for national decline, reasons for non‐recruitment, number of kidneys recruited and assessed, and reasons for decline and for not transplanting. DCD, donation after circulatory death; WIT, warm ischaemia time; CIT, cold ischaemia time; QAS, quality assessment score

Eight of the ten recruited kidneys were declined primarily owing to inadequate in situ perfusion; one of these also had a stripped ureter. One kidney was from a donor who had undergone 109 min of normothermic regional perfusion before organ retrieval11, 12. The remaining two kidneys, which were from the same donor, were declined because of age (78 years). The donor demographics are detailed in Table S1 (supporting information). The appearance of the kidneys with inadequate in situ perfusion ranged from a global mottled appearance to areas of segmental non‐perfusion covering 20–50 per cent of the organ.

Perfusion parameters

All kidneys were perfused for 60 min at mean(s.d.) arterial BP of 77(5) mmHg/ml and temperature of 35·3(0·2) °C.

Five of the ten kidneys were not transplanted. The first (K03) had a QAS score of 3 but, owing to delayed access to the operating theatre, which would prolong the cold ischaemia time further, the decision was made by the implanting surgeon not to transplant the kidney. The second (K04) also had a QAS score of 3. Before NMP, the kidney was mottled globally. Despite renal blood flow above the threshold, the global appearance was unchanged after perfusion when the kidney was flushed with cold preservation solution, and the decision not to transplant was made by the transplanting surgeon. The pair of kidneys from the 78‐year‐old donor had a QAS score of 1 (left kidney) and 4 (right). However, the Remuzzi scores were 6 and 7 respectively, and the kidneys were deemed not suitable for transplantation13. The last kidney (K10) had a QAS score of 4 and was therefore considered unsuitable for transplantation.

Five kidneys were transplanted successfully (Table 3). The first pair (K01 and K02) had QAS values of 1 and 2 respectively. K05 had a QAS of 3; this kidney also had a stripped ureter. The kidney was a little patchy at the start of perfusion but improved thereafter. The ureter was vascularized adequately. The kidney also had an upper polar artery that had been cut, and this was ligated leading to a 3 × 3‐cm area of infarction. The last pair (K08 and K09) had QAS values of 2.

Table 3.

Clinical data for transplanted kidneys and demographics of the recipients

| K01 | K02 | K05 | K08 | K09 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transplanted kidneys | |||||

| First CIT (h) | 17·4 | 19·7 | 18·9 | 7·8 | 9·5 |

| NMP (min) | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

| Second CIT (min) | 132 | 247 | 187 | 503 | 187 |

| Anastomosis (min) | 33 | 33 | 39 | 34 | 38 |

| Total duration of ischaemia (h) | 21·2 | 26·4 | 23·7 | 17·8 | 14·2 |

| Recipients | |||||

| Age | 30 | 68 | 55 | 49 | 45 |

| Sex | M | F | M | M | M |

| HLA mismatch | 0‐1‐1 | 2‐1‐0 | 2‐2‐0 | 2‐1‐0 | 2‐1‐0 |

| Previous transplant | No | No | No | Yes 1 | No |

| Dialysis | HD | CAPD | HD | HD | CAPD |

| Delayed graft function | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Creatinine (μmol/l) | |||||

| Before transplant | 834 | 558 | 733 | 741 | 588 |

| 7 days | 115 | 550 | 681 | 600 | 311 |

| 1 month | 101 | 143 | 514 | 155 | 175 |

| 3 months | 106 | 143 | 408 | 116 | 167 |

| 6 months | 124 | 192 | 292 | ||

| Acute rejection | No | No | No | No | No |

| Duration of hospital stay (days) | 5 | 9 | 9 | 7 | 6 |

CIT, cold ischaemia time; NMP, normothermic machine perfusion; HD, haemodialysis; CAPD, continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis.

After NMP, the kidneys were flushed with cold preservation solution then stored on ice until transplantation. This second cold ischaemia time ranged from 132 to 503 min. The total amount of urine produced during NMP was significantly less in the kidneys that were not transplanted (mean 344(172) versus 41(29) ml for transplanted and not transplanted kidneys respectively; P = 0·008) (Fig. 2). There were no other significant differences in the perfusion parameters between the transplanted and non‐transplanted kidneys. Urinary levels of NGAL were numerically lower in the transplanted kidneys (P = 0·055) (Fig. S1, supporting information).

Figure 2.

a Mean(s.d.) renal blood flow during normothermic perfusion of the transplanted and non‐transplanted kidneys and b total urine output. Values for individual patients are also shown

Outcomes

One patient (K05) had delayed graft function requiring dialysis for 3 weeks after transplant (Table 3). The 3‐month biopsy showed ongoing acute tubular necrosis with some tacrolimus toxicity. Kidney function improved with the serum creatinine level falling from 408 μmol/l at 3 months to 292 μmol/l at 6 months. K08 required one episode of dialysis after transplant owing to hyperkalaemia. The mean(s.d.) hospital stay was 7·2(1·8) days.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that NMP technology can be used to assess and transplant DCD kidneys that have previously been deemed unsuitable for transplantation. Five kidneys were transplanted successfully after being rejected, primarily owing to inadequate in situ perfusion in the donor. This is the only current experience of the transplantation of human kidneys that had been deemed unsuitable for transplantation. Four of five transplants functioned immediately without recourse to dialysis. The only kidney with delayed graft function had suboptimal renal function, with a recipient serum creatinine of 292 μmol/l at 6 months. This kidney had a QAS of 3, which was the highest value in the transplanted group. The level of NGAL measured in the urine after NMP was also high in this kidney, suggesting poorer quality. NGAL is a marker of tubular injury, and has been found previously to have a strong association with NMP functional parameters and donor history14. Further experience, and possibly refinement of the QAS, may be required to achieve an acceptably low incidence of suboptimal results.

There was a low yield of transplanted kidneys from the potential pool of declined DCD organs. Over a 14‐month interval, 55 declined DCD kidneys were offered to the study, but only ten of these proceeded to NMP assessment with intent to transplant them. Eight kidneys undergoing NMP assessment were declined because of inadequate in situ perfusion in the donor and two were from an older donor. The reasons for not proceeding to NMP assessment in 45 of the 55 kidneys offered were often multifactorial, and included suspected malignancy, adverse renal anatomy, vascular damage, past medical history such as severe hypertension and diabetes, infection and prolonged cold ischaemia. The low yield of transplanted kidneys has been a reflection of a relatively cautious approach at the start of this initiative.

Inadequate in situ perfusion is common in DCD kidney transplantation14, 15. The accumulation of thrombi in the microcirculation, anatomy of the kidney, improper placement of the perfusion cannula, vasospasm, atherosclerosis and renal artery stenosis can be contributing factors. It has been demonstrated previously14, and confirmed here, that a large proportion of kidneys declined because of inadequate in situ perfusion can regain function during NMP and, based on the perfusion parameters, may be suitable for transplantation. In the phase 1 study, 18 of the 42 kidneys (43 per cent) were declined owing to inadequate in situ perfusion, and three‐quarters of these kidneys had a QAS score of 1 to 3, suggesting potential suitability for transplantation.

Prolonged cold storage was the commonest reason for not proceeding to assessment by NMP in phase 2. Cold storage time is an independent risk factor for reduced graft survival and is associated with delayed graft function16, 17. DCD kidneys have, by definition, had a period of warm ischaemia and are especially sensitive to added cold ischaemic injury17. This informed the cautious approach here to kidneys with prolonged cold ischaemia. The kidneys recruited into this study were offered as research kidneys after being declined through the national organ‐sharing and the fast‐tracking schemes. The current logistics of the allocation system meant that prolonged cold ischaemia times were often unavoidable. The cold ischaemia time before NMP was in excess of 16 h in three of the five transplanted kidneys in this series. The total ischaemia time was over 24 h in one kidney and approached 24 h in another two. The authors were particularly reluctant to recruit kidneys that were offered with a combination of older donor age and prolonged cold ischaemia, as this combination of factors is known to be associated with poor outcomes16. Furthermore, the Cambridge unit has a policy that mandates histological assessment of all kidneys from donors aged 60 years or more. Pretransplant biopsies are assessed using the Remuzzi scoring system9, 18. Although this can provide valuable information on chronic damage it also prolongs the cold ischaemia time by 4–6 h.

After NMP the kidney must be flushed with cold preservation solution to clear the microcirculation of the red cell‐based perfusion solution. The kidney is then stored in ice until transplantation. This inevitable second interval of cold ischaemia lasted more than 2 h in all five transplanted kidneys; the longest duration was 8·4 h. The principle of intermediate NMP followed by a relatively long second cold storage period has already been described19. This suggests that it would be possible to have regional perfusion hubs that assessed marginal kidneys by NMP and then repackaged suitable organs in ice for transport to another centre for transplantation. This concept has already been established for ex vivo lung perfusion20.

NMP allows the successful transplantation of DCD kidneys that had been deemed unsuitable for transplantation, and has potential to increase the number of kidney transplants. There is, however, a pressing need to access declined DCD kidneys more quickly in order to increase the rate of assessment by NMP and the transplant rate.

Supporting information

Figure S1. (A) Oxygen consumption, (C) Quality Assessment (QAS) score and (D) urinary levels of neutrophil gelatinase‐associated lipocalin (NGAL) measured by ELISA.

Table S1 Phase 2, donor demographics, ischaemic times and reason for decline in the 10 recruited kidneys.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Kidney Research UK, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre and the NIHR Blood and Transplant Research Unit in Organ Donation and Transplantation at the University of Cambridge, in collaboration with Newcastle University and in partnership with National Health Service Blood and Transplant (NHSBT). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the NIHR, the Department of Health or NHSBT.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Presented to a meeting of the Society of Academic and Research Surgery, Dublin, Ireland, January 2017; published in abstract form as Br J Surg 2017; 104(Suppl 3): 23

References

- 1. Johnson RJ, Bradbury LL, Martin K, Neuberger J; Transplant Registry UK. Organ donation and transplantation in the UK – the last decade: a report from the UK national transplant registry. Transplantation 2014; 97(Suppl 1): S1–S27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Summers DM, Watson CJ, Pettigrew GJ, Johnson RJ, Collett D, Neuberger JM et al Kidney donation after circulatory death (DCD): state of the art. Kidney Int 2015; 88: 241–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lim WH, McDonald SP, Russ GR, Chapman JR, Ma MK, Pleass H et al Association between delayed graft function and graft loss in donation after cardiac death kidney transplants – a paired kidney registry analysis. Transplantation 2017; 101: 1139–1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. NHS Blood and Transplant . NHSBT Organ Donation and Transplantation Activity Report 2015/2016 https://nhsbtdbe.blob.core.windows.net/umbraco-assets-corp/1452/activity_report_2015_16.pdf [accessed 27 April 2017]

- 5. Hosgood SA, Nicholson ML. First in man renal transplantation after ex vivo normothermic perfusion. Transplantation 2011; 92: 735–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nicholson ML, Hosgood SA. Renal transplantation after ex vivo normothermic perfusion: the first clinical study. Am J Transplant 2013; 13: 1246–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zalewska K. Clinical Contraindications to Approaching Families for Possible Organ Donation. Policy POL188/5.2 http://odt.nhs.uk/pdf/contraindications_to_organ_donation.pdf [accessed 7 October 2017]

- 8. Hosgood, SA , Barlow AD, Hunter JP, Nicholson ML. Ex vivo normothermic perfusion for quality assessment of marginal donor kidney transplants. Br J Surg 2015; 102: 1433–1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Remuzzi G, Cravedi P, Perna A, Dimitrov BD, Turturro M, Locatelli G et al Long‐term outcome of renal transplantation from older donors. N Engl J Med 2006; 354: 343–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lee AP, Abramowicz D. Is the kidney donor risk index a step forward in the assessment of deceased donor kidney quality? Nephrol Dial Transplant 2015; 30: 1285–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Messer SJ, Axell RG, Colah S, White PA, Ryan M, Page AA et al Functional assessment and transplantation of the donor heart after circulatory death. J Heart Lung Transplant 2016; 35: 1443–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. De Carlis R, Di Sandro S, Lauterio A, Ferla F, Dell'Acqua A, Zanierato M et al Successful donation after cardiac death liver transplants with prolonged warm ischemia time using normothermic regional perfusion. Liver Transpl 2017; 23: 166–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ruggenenti P, Perico N, Remuzzi G. Ways to boost kidney transplant viability: a real need for the best use of older donors. Am J Transplant 2006; 6: 2543–2547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hosgood SA, Barlow AD, Dormer J, Nicholson ML. The use of ex‐vivo normothermic perfusion for the resuscitation and assessment of human kidneys discarded because of inadequate in situ perfusion. J Transl Med 2015; 13: 329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Callaghan CJ, Harper SJ, Saeb‐Parsy K, Hudson A, Gibbs P, Watson CJ et al The discard of deceased donor kidneys in the UK. Clin Transplant 2014; 28: 345–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ubert O, Kamar N, Vernerey D, Viglietti D, Martinez F, Duong‐Van‐Huyen JP et al Long term outcomes of transplantation using kidneys from expanded criteria donors: prospective, population based cohort study. BMJ 2015; 351: h3557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Summers DM, Johnson RJ, Hudson A, Collett D, Watson CJ, Bradley JA. Effect of donor age and cold storage time on outcome in recipients of kidneys donated after circulatory death in the UK: a cohort study. Lancet 2013; 381: 727–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mallon DH, Riddiough GE, Summers DM, Butler AJ, Callaghan CJ, Bradbury LL et al Successful transplantation of kidneys from elderly circulatory death donors by using microscopic and macroscopic characteristics to guide single or dual implantation. Am J Transplant 2015; 15: 2931–2939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hosgood SA, Nicholson ML. The first clinical case of intermediate ex vivo normothermic perfusion in renal transplantation. Am J Transplant 2014; 14: 1690–1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yeung JC, Cypel M, Keshavjee S. Ex‐vivo lung perfusion: the model for the organ reconditioning hub. Curr Opin Organ Transplant 2017; 22: 287–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. (A) Oxygen consumption, (C) Quality Assessment (QAS) score and (D) urinary levels of neutrophil gelatinase‐associated lipocalin (NGAL) measured by ELISA.

Table S1 Phase 2, donor demographics, ischaemic times and reason for decline in the 10 recruited kidneys.