Abstract

Objectives. To compare population-based sterilization rates between Latinas/os and non-Latinas/os sterilized under California’s eugenics law.

Methods. We used data from 17 362 forms recommending institutionalized patients for sterilization between 1920 and 1945. We abstracted patient gender, age, and institution of residence into a data set. We extracted data on institution populations from US Census microdata from 1920, 1930, and 1940 and interpolated between census years. We used Spanish surnames to identify Latinas/os in the absence of data on race/ethnicity. We used Poisson regression with a random effect for each patient’s institution of residence to estimate incidence rate ratios (IRRs) and compare sterilization rates between Latinas/os and non-Latinas/os, stratifying on gender and adjusting for differences in age and year of sterilization.

Results. Latino men were more likely to be sterilized than were non-Latino men (IRR = 1.23; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.15, 1.31), and Latina women experienced an even more disproportionate risk of sterilization relative to non-Latinas (IRR = 1.59; 95% CI = 1.48, 1.70).

Conclusions. Eugenic sterilization laws were disproportionately applied to Latina/o patients, particularly Latina women and girls. Understanding historical injustices in public health can inform contemporary public health practice.

The legacy of US eugenic sterilization laws, which 32 states used to prevent the reproduction of individuals deemed “unfit,” continues to surface in discussions of contemporary public health issues, including reproductive autonomy,1 medical mistrust,2 and prenatal genomic testing. Although public health professionals are periodically reminded of this history,3 few studies document the scale and demographics of the population sterilized by state actors. Of particular concern is the disproportionate sterilization of people of color, which has been noted in historical literature but rarely quantified.4 Disproportionate sterilization of racialized minorities is an important historical backdrop for ongoing conversations about reproductive health equity1 and implicit bias5 and structural racism6 in health care.

We used data from the California state eugenics program, the United States’ most active sterilization program,7 to examine dynamics of sterilization for Californians of Latin American descent (today described as Latinas/os) relative to Californians of other origins. Although the historical context that resulted in disproportionate sterilization of Latinas/os, particularly those of Mexican origin, during this period has been articulated,8 the total scope of anti-Latina/o bias in sterilization is unknown.

California passed the nation’s third eugenic sterilization law in 1909 and performed one third, or 20 000, of all documented compulsory sterilizations conducted under state eugenics laws.3 California’s eugenic sterilization law authorized medical superintendents in state homes and hospitals to sterilize patients classified as “feebleminded” or having conditions thought “likely to be transmitted to descendants.”9 Sterilizations declined after the law was revised in the early 1950s.

Although eugenic sterilization programs did not designate specific racial/ethnic groups for sterilization, existing racial taxonomies that constructed Whites as superior, along with class hierarchies and prejudices against people with disabilities, shaped who would be deemed fit and unfit in California’s eugenics program.8 Biases against Mexicans and Mexican Americans were especially prominent: institutional authorities described Mexicans and their descendants as “immigrants of an undesirable type” and speculated that they were at a “lower racial level than is found among American Whites.”10

To better understand the racialized implementation of California eugenics, we evaluated whether institution residents of Latina/o origin were disproportionately sterilized. The term “Latina/o” was not in use during this period, but we use it to refer to immigrant or US-born individuals of Latin American heritage, primarily Mexican origin, who were cast as racially inferior and unfit during the period examined.

METHODS

We used data from more than 20 000 sterilization recommendation forms from the California Department of Mental Health (now the Department of State Hospitals). We digitized records and abstracted them into a data set, which is described in detail elsewhere.7,11 Sterilization recommendations are not proof of sterilization, but the recommendation process was the primary mechanism through which compulsory sterilizations were authorized in institutions.

We restricted our analysis to individuals recommended for sterilization between 1920 and 1945 (n = 17 852) because denominator US Census data are not available after 1940. We used data on each patient’s institution, year of sterilization recommendation, age, and gender. We used the 1980 US Census list of Spanish surnames to identify patients of Latin American heritage as a racialized group because racial/ethnic origin was not systematically recorded on sterilization recommendations. We excluded individuals missing data on institution, gender, or age (n = 490), leaving 17 362 records in the analytic sample.

We created population denominators using US Census microdata from 1920, 1930, and 1940 (https://www.ipums.org/doi/D010.V6.0.shtml) and restricted analyses to patients living in California state institutions in each census year: n = 11 110 (1920), 15 566 (1930), and 27 257 (1940). We linearly interpolated data between census years to create annual denominators for sterilization rates. We created interpolation slopes at the institution level using counts according to gender, age, and Spanish surname. We extended counts from 1940 forward to 1945. For institutions that opened during the study period, we extended counts from the following census back to the year each institution opened.

We used the number of sterilization recommendations and interpolated the number of institution residents stratified by institution, gender, Spanish surname, age group, and year. For descriptive analyses, we visually examined temporal trends in sterilization by Spanish surname and gender using locally estimated scatterplot smoothing curves of population-based sterilization rates. To evaluate Spanish surname differences in sterilization, we used Poisson regression of the number of sterilizations, with Spanish surname as the independent variable, using census denominators as the offset, and including a random effect for institution to account for differences in sterilization practices between institutions. Because the medical procedures and rationales motivating sterilization differed for women and men, we estimated all models stratified by gender. We adjusted for age and period to account for differences in the age structure of the Spanish surname and non–Spanish surname populations and for temporal differences in population composition. We conducted statistical analysis with Stata version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

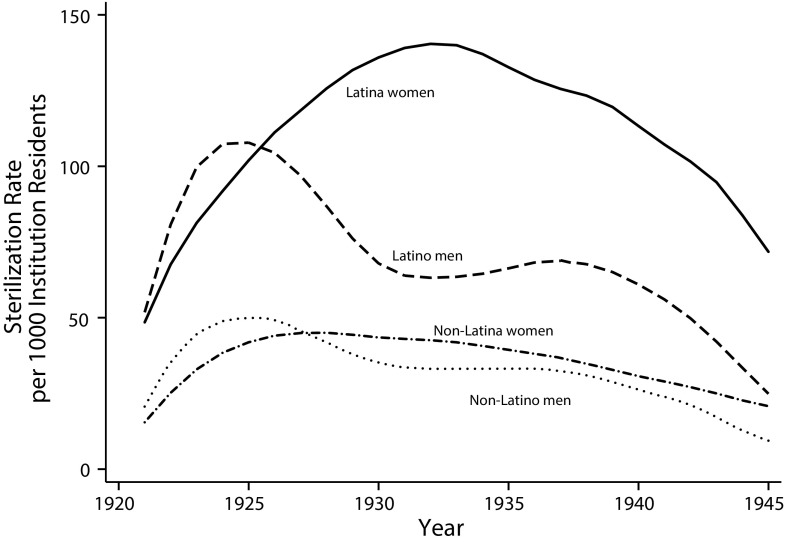

In total, 17 362 individuals were recommended for sterilization in California state homes and hospitals between 1920 and 1945 (Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Locally estimated scatterplot smoothing plots of sterilization rates (Figure 1) indicated that Latinas/os were at the highest risk of sterilization for the entire period. From 1920 to about 1926, men had higher sterilization rates than did women. After 1926, women were sterilized at higher rates than were males.

FIGURE 1—

Locally Estimated Scatterplot Smoothing Plots of Sterilization Rates Among Patients in California State Institutions, by Gender and Latina/o Ethnicity: 1920–1945

Using gender-stratified Poisson regression, we found that Latino men were at 23% greater risk of sterilization than were non-Latino men, accounting for age and period of sterilization (incidence rate ratios [IRR] = 1.23; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.15, 1.31; Table B, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Anti-Latina/o bias in sterilization was greater among women, with Latinas at 59% greater risk of sterilization than non-Latinas (IRR = 1.59; 95% CI = 1.48, 1.70).

DISCUSSION

We drew on a new, rich source of microdata to quantify the disproportionate sterilization of Latinas/os, most of whom were of Mexican origin, in California’s eugenics program. We found higher rates of sterilization for Latinas/os (especially Latinas) than non-Latinas/os.

Eugenic thinking inscribed “scientific” legitimacy to racial stereotypes of Latinas/os as inferior and unfit to reproduce. In California, eugenics programs were linked to efforts to reduce immigration, particularly from Mexico, during a time when growing anti-Mexican sentiment manifested in school segregation and racial housing covenants.12 Mexican American women and adolescents were particularly stereotyped as “hyperfertile,” inadequate mothers, criminally inclined, and more prone to feeblemindedness.8

Our finding of disproportionate sterilization of Latinas/os in California aligns with an empirical study of racial inequities in sterilization in North Carolina,4 but our individual-level data allowed us to consider gender and age.

Limitations

Spanish surname is an imperfect criterion for identifying Latina/o individuals but has high sensitivity and specificity for identifying individuals of Latin American or Spanish descent, particularly in mid–20th-century California. In 1950, the first census year for which the Census Bureau compared Spanish surname criteria with national origin data, 88% of Spanish surname individuals in California were of Mexican descent (www2.census.gov/prod2/decennial/documents/41601756v4p3ch07.pdf).

Another limitation of the analysis is that it is not possible to confirm which individuals recommended for sterilization were ultimately sterilized.

Conclusions

Understanding public health’s role in systemic abuses, such as eugenic sterilization, can contextualize the growing literature documenting racial discrimination and implicit racial bias in health care.5 Disproportionate coercive sterilization of Latinas/os in California did not end with the decline of the state’s eugenics program but continued at other sites, including hospitals and prisons. Our research provides insight into the historical construction of racial stereotypes and how they worked to justify compulsory sterilization in a specific context. This perspective may offer lessons when examining contemporary inequities in health and health care.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the National Human Genome Research Institute (grant R21 HG009205-01) for funding support and the University of Michigan MCubed program for pilot support. S. D. H. gratefully acknowledges use of the services and facilities of the Population Studies Center at the University of Michigan (funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development [grant R24 HD041028]). The REDCap data capture tools are funded by the Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research (grant CTSA: UL1TR000433).

Note. The funding sources had no involvement in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

The institutional records analyzed for this study were used in accordance with the institutional review board protocols of the California Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects and the University of Michigan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gubrium AC, Mann ES, Borrero S et al. Realizing reproductive health equity needs more than long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) Am J Public Health. 2016;106(1):18–19. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumanyika SK, Morssink CB, Nestle M. Minority women and advocacy for women’s health. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(9):1383–1388. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.9.1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stern AM. Sterilized in the name of public health: race, immigration, and reproductive control in modern California. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(7):1128–1138. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.041608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Price GN, Darity WA., Jr The economics of race and eugenic sterilization in North Carolina: 1958–1968. Econ Hum Biol. 2010;8(2):261–272. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper LA, Roter DL, Carson KA et al. The associations of clinicians’ implicit attitudes about race with medical visit communication and patient ratings of interpersonal care. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):979–987. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feagin J, Bennefield Z. Systemic racism and US health care. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stern AM, Novak NL, Lira N, O’Connor K, Harlow S, Kardia S. California’s sterilization survivors: an estimate and call for redress. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(1):50–54. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lira N, Stern AM. Mexican Americans and eugenic sterilization. Aztlan. 2014;39(2):9–34. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laughlin HH. Eugenical Sterilization in the United States. Chicago, IL: Psychopathic Laboratory of the Municipal Court of Chicago; 1922. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terman LM, Williams JH, Fernald GM. Surveys in Mental Deviation in Prisons, Public Schools, and Orphanages in California. Sacramento, CA: California State Printing Office; 1918. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sánchez GJ. Becoming Mexican American: Ethnicity, Culture, and Identity in Chicano Los Angeles, 1900–1945. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]