Abstract

Objective

Although generally classified within the group of inflammatory myopathies, JDM displays many pathological features of vasculitis. Previous work has shown that AECA are abundant in other forms of vasculitis. We therefore investigated whether such antibodies might also be detected in JDM.

Methods

We screened plasma from children with JDM for the presence of AECA by western blotting and 2D gel electrophoresis (2DE) using proteins extracted from human aortic endothelial cells as the substrate. We performed mass spectrometry to identify candidate antigens from 2DE gels and used ELISA to confirm the presence of specific antibodies.

Results

We identified 22 candidate target autoantigens for AECA probed with JDM plasma. Interestingly, 17 of these 22 target antigens were proteins associated with antigen processing and protein trafficking. ELISA confirmed the presence of antibodies to heat shock cognate 71 kDa protein in JDM plasma, particularly in children with active, untreated disease.

Conclusion

Children with JDM express antibodies to autoantigens in endothelial cells. The clinical and pathological significance of such autoantibodies require further investigation.

Keywords: juvenile dermatomyositis, autoantibodies, anti-endothelial cell antibodies, heat shock cognate 71 kDa protein, endothelium, chaperone proteins, proteomics

Rheumatology key messages

Anti-endothelial cell antibodies are present in plasma of children with JDM.

Antibodies to heat shock cognate 71 kDa protein may serve as useful biomarkers in JDM.

Introduction

JDM is the most common form of inflammatory myopathy in children [1]. Although classified as a myopathy, involved tissues in JDM are characterized by prominent vascular and perivascular inflammation that contributes directly to the clinical features of the disease [2]. Indeed, one of the earliest descriptions of JDM in the English language, the classic paper by Banker and Victor, described JDM as ‘… systemic angiopathy … of childhood’ [3]. Thus, JDM can also be regarded as a form of vasculitis.

Autoantibody expression involving a broad spectrum of autoantigens is a well-documented feature of JDM [1, 4]. These autoantibodies have specific clinical associations, but their relationship to disease pathology remains unclear. These autoantibodies are typically identified by immunoprecipitating protein or DNA from radiolabelled HeLa or K562 cell extracts and double immunodiffusion [1], and thus the actual in vivo cellular targets of these autoantibodies remain unclear. We have recently demonstrated that several forms of vasculitis are associated with autoantibody responses to endothelial cells [5, 6], and the presence or titre of these autoantibodies may serve as biomarkers of disease or to monitor disease activity. The studies described here were undertaken to determine whether the endothelium in JDM might similarly be targeted by autoantibodies.

Methods

Patients

Plasma of patients with JDM (n = 39) were collected from the University of Oklahoma Pediatric Rheumatology clinic between 2007 and 2011. The mean (s.d.) age of the patients with JDM (28 females and 11 males) was 9 (4) years, with a range of 3–16. Children with active JDM had disease durations ranging from 4 months to 3 years, and were being treated with weekly injectable MTX (25 mg/m2 body surface area), daily oral steroids (<1.0 mg/kg/day) and pulse methylprednisolone given at a dose of 500 mg/m2 body surface area for intervals ranging from once a week to once a month. Children with inactive disease who were on maintenance therapy with weekly injectable MTX were 11–48 months post-diagnosis. Active disease was defined as the presence of any of the following: JDM-associated rash, periungual capillary abnormalities (dilatation, drop-out) or elevations in serum levels of creatine phodphokinase or aldolase. Elevations of aspartate amino transferase or alanine amino transferase were considered signs of active disease if MTX-associated hepatic injury was excluded based on clinical grounds and normal serum levels of gamma glutamyl transferase. Plasma of patients with JIA (n = 15, 13 females and 2 males) and healthy children (n = 20, 11 females and 9 males) were collected from the University of Oklahoma and the General Pediatrics clinic at the Women and Children’s Hospital of Buffalo. Healthy children with the mean age of 12 (4) years (range, 4–17 years) and JIA with the mean age of 9 (4) years (range, 4–14 years) were included in this study. The patients with JIA included five children with untreated, active disease, five children with active disease on therapy with weekly MTX + NSAIDs (disease duration 2–9 months) and five children on MTX + etanercept who fit criteria for clinical remission on medication [7]. Informed consent, and, where appropriate, assent, was obtained from all participants prior to obtaining samples. This study was approved by the ethics committee of St Marianna University School of Medicine (No.1710) and by the University of Oklahoma (#12134) and University at Buffalo (IRB # MOD 00002155) Institutional Review Boards.

Cell culture

Normal human aortic endothelial cells (HAEC), human aortic adventitial fibroblasts (AoAF) and human skeletal muscle cells (SkMC), and culture media and supplements for HAEC, AoAF and SkMC were obtained from Lonza (Walkersville, MD, USA). Normal human dermal microvascular endothelial cells (HMVEC-D) were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Culture media and supplements for HMVEC-D were obtained from Kurabo Industries (Osaka, Japan). Normal human aortic smooth muscle cells (HAoSMC) was obtained from Lifeline Cell Technology (Frederick, MD, USA). Culture media and supplements for HAoSMC were obtained from Kurabo Industries (Osaka, Japan). All cells were cultured in the media and supplements as described previously [5]. Cells at passages 1–4 were harvested and stored at −80 °C until use for 2D gel electrophoresis (2DE) or SDS–PAGE.

2D gel electrophoresis

2DE was conducted as described previously [5] with the following modifications. Protein (400 µg) from the harvested HAEC was applied onto Immobiline DryStrip gels (pH3.0–10.0; GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden). After electrophoresis, one gel was used for Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 staining and the other gel was used for transfer of the separated proteins onto a nitrocellulose membrane for western blotting (WB).

SDS–PAGE

SDS–PAGE was conducted as described previously [5]. To detect AECA, proteins extracted from HAEC, HMVEC-D, AoAF, HAoSMC and SkMC were used for SDS–PAGE and WB. 20 µg of extracted proteins were applied to 12.5% SDS–PAGE gels, after which the separated proteins on the gels were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes for WB.

Western blotting

WB after SDS–PAGE or 2DE was performed as described previously [5]. Plasma from patients with JDM were used for SDS–PAGE (five samples) or 2DE (three samples) at a final dilution of 1:100 (1:500 for each donor in SDS–PAGE) or that of 1:100 (1:300 for each donor in 2DE). Then the bound antibodies were reacted with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-human IgG diluted 1:2000. Finally, the bound IgG antibodies were visualized using diaminobenzidine.

Protein identification

In-gel digestion was performed as described previously [5]. Analysis of peptides was carried out using an liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) system, which consisted of a nano ultra high performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-quadrupole time-of-flight system (maXis-4 G-CPR; Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA, USA). A L-column octadecylsilane–bonded silica [L-column ODS], 0.075 × 150 mm, 3 μm particle size, Chemicals Evaluation Research Institute (CERI), Tokyo, Japan] was used. The eluted peptides were directly electro-sprayed into the spectrometer, with MS/MS spectra acquired in a data-dependent mode. Database searches in the SwissProt database were performed using the Mascot 2.5.1 (Matrix Science, Boston, MA, USA) incorporated into ProteinScape3.1 (Bruker Daltonics, Billereica, MA).

ELISA

ELISA was conducted as described previously [5]. To detect antibodies to heat shock cognate 71 kDa protein (HSC70) in plasma, each well of an ELISA plate was coated with 0.125 µg of HSC70 (StressMarq Biosciences, Victoria, BC, Canada) in a carbonate buffer (50 mM sodium carbonate, pH 9.6). The plasma diluted 1:200 with 10% Block Ace were reacted with the coated recombinant proteins. Optical density at 490 nm was measured by a microplate reader. The average plus 2 s.d. among the group of healthy donors was defined as 100 arbitrary binding units and was used as a cut-off point for determining reactivity to HSC70.

Statistics

Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the frequency of each antibodies between each of the phenotypes and JDM disease states.

Results

Detection of antibodies in patients with JDM

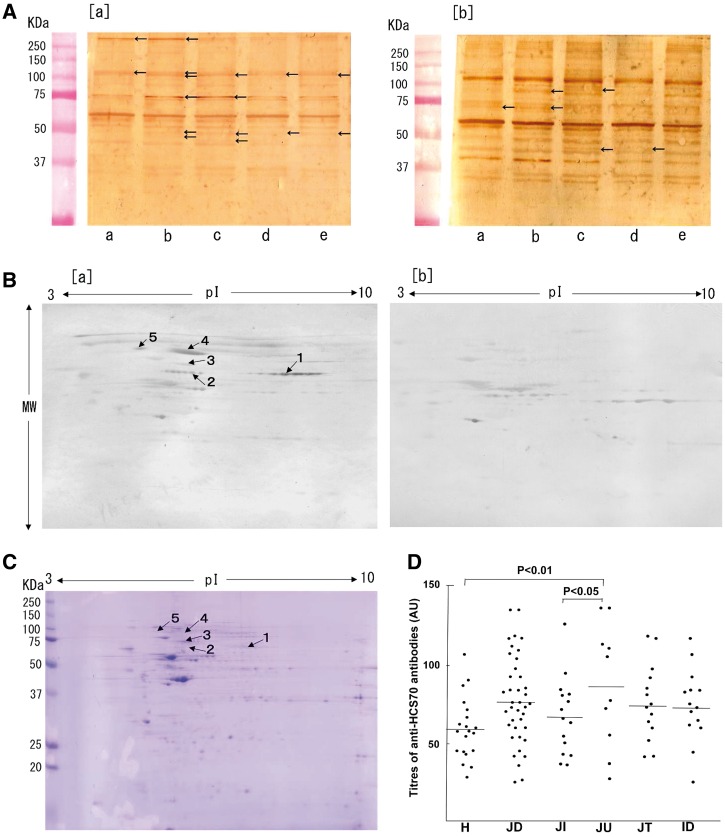

To select the best antigen source, we first detected autoantibodies in plasma from patients with JDM, both active patients without treatment and inactive patients (off medication) using proteins extracted from five different cells by WB [Fig. 1A (a) and (b)]. Multiple antigens were detected in each cell line, in particular HAEC. Among three types of cells derived from aorta (HAEC, AoAF and HAoSMC), staining patterns appeared to differ most between the HAEC and the other cell lines. We also noted distinct differences in the staining patterns between patients with active JDM and patients with inactive JDM. In plasma from patients with inactive JDM, differences in staining patterns between each cell line were not significant. Based on these results, HAEC were used for 2DE to facilitate identification of specific antigens. We limited 2DE studies to plasma samples from active patients without treatment.

Fig. 1.

Detection of AECA in JDM

(A) Protein extracted from normal human dermal microvascular endothelial cells (HMVEC-D) (a), normal human aortic endothelial cells (HAEC) (b), human aortic adventitial fibroblasts (AoAF) (c), normal human aortic smooth muscle cells (HAoSMC) (d) and human skeletal muscle cells (SkMC) (e) were separated by SDS–PAGE. Proteins reactive to plasma from patients with active JDM (untreated: a) or patients with inactive JDM (off therapy: b) were detected by western blotting (WB). (B) Proteins extracted from HAEC separated by 2D gel electrophoresis (2DE), and antigens detected by WB using plasma from patients with active JDM [untreated (a) or healthy (b) children]. Protein spots in AECA recognized predominantly in JDM compared with control plasma are indicated by arrows and spot ID numbers in (a). (C) Locations of the five protein spots analysed by MS are indicated in a Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250-stained 2DE gel using HAEC extracts. (D) Results of ELISA assays for anti-HSC70 antibodies. H: healthy children; JD: JDM; JI: JIA; JU: untreated JDM, active disease; JT: treated JDM, active disease; ID: inactive JDM.

Candidate antigens for AECA detected in JDM by 2DE-WB

To detect JDM-specific antigens on HAEC, results of 2DE-WB using plasma from untreated JDM patients with active disease [Fig. 1B (a)] were compared with results from plasma from healthy children [Fig. 1B (b)]. Five candidate protein spots were detected in 2DE-WB [arrows, Fig. 1B (a) and C]. Twenty-two proteins from five protein spots recovered from 2DE gels were identified using mass spectrometry (Table 1).

Table 1.

Identification of candidate antigens for AECA in patients with JDM

| Spot no. | Protein name | Accession no. | Accession ID | MW (kDa)/pI | MS/MS analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Theoretical | Coverage (%) | No. of matched peptides | ||||

| 1 | Prelamin-A/C | P02545 | LMNA_HUMAN | 69/6.5 | 74/6.57 | 35.40 | 27 |

| Dihydropyrimidinase-related protein 2 | Q16555 | DPYL2_HUMAN | 69/6.5 | 62/5.95 | 5.80 | 3 | |

| Stress-induced-phosphoprotein 1 | P31948 | STIP1_HUMAN | 69/6.5 | 63/6.40 | 7.40 | 3 | |

| T-complex protein 1 subunit zeta | P40227 | TCPZ_HUMAN | 69/6.5 | 58/6.24 | 5.80 | 3 | |

| Cytoskeleton-associated protein 4 | Q07065 | CKAP4_HUMAN | 69/6.5 | 66/5.63 | 5.80 | 2 | |

| 2 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K | P61978 | HNRPK_HUMAN | 69/5.2 | 51/5.39 | 33.50 | 25 |

| Cytoskeleton-associated protein 4 | Q07065 | CKAP4_HUMAN | 69/5.2 | 66/5.63 | 29.40 | 13 | |

| Prelamin-A/C | P02545 | LMNA_HUMAN | 69/5.2 | 74/6.57 | 11.60 | 6 | |

| T-complex protein 1 subunit theta | P50990 | TCPQ_HUMAN | 69/5.2 | 60/5.41 | 12.20 | 5 | |

| Tubulin alpha-1A chain | Q71U36 | TBA1A_HUMAN | 69/5.2 | 50/4.94 | 9.10 | 2 | |

| Dihydropyrimidinase-related protein 2 | Q16555 | DPYL2_HUMAN | 69/5.2 | 62/5.95 | 3.10 | 2 | |

| 3 | Heat shock cognate 71 kDa protein | P11142 | HSP7C_HUMAN | 75/5.4 | 71/5.37 | 42.70 | 41 |

| Heat shock 70 kDa protein 1-like | P34931 | HS71L_HUMAN | 75/5.4 | 70/5.75 | 14.50 | 9 | |

| Stress-70 protein, mitochondrial | P38646 | GRP75_HUMAN | 75/5.4 | 74/5.87 | 12.70 | 7 | |

| Annexin A6 | P08133 | ANXA6_HUMAN | 75/5.4 | 76/5.41 | 6.40 | 4 | |

| Lamin-B1 | P20700 | LMNB1_HUMAN | 75/5.4 | 66/5.11 | 13.50 | 5 | |

| V-type proton ATPase catalytic subunit A | P38606 | VATA_HUMAN | 75/5.4 | 68/5.34 | 5.00 | 3 | |

| 4 | Protein-glutamine gamma-glutamyltransferase 2 | P21980 | TGM2_HUMAN | 90/5.1 | 77/5.11 | 34.10 | 23 |

| HSP 90-beta | P08238 | HS90B_HUMAN | 90/5.1 | 83/4.96 | 16.70 | 12 | |

| Protein Hook homolog 3 | Q86VS8 | HOOK3_HUMAN | 90/5.1 | 83/5.12 | 9.70 | 5 | |

| Src substrate cortactin | Q14247 | SRC8_HUMAN | 90/5.1 | 62/5.24 | 7.80 | 4 | |

| Ran GTPase-activating protein 1 | P46060 | RAGP1_HUMAN | 90/5.1 | 64/4.63 | 6.60 | 2 | |

| Plastin-2 | P13796 | PLSL_HUMAN | 90/5.1 | 70/5.29 | 2.10 | 2 | |

| 5 | Hematopoietic lineage cell-specific protein | P14317 | HCLS1_HUMAN | 93/4.5 | 54/4.73 | 16.70 | 11 |

| HSP 90-beta | P08238 | HS90B_HUMAN | 93/4.5 | 83/4.96 | 14.90 | 10 | |

| Protein-glutamine gamma-glutamyltransferase 2 | P21980 | TGM2_HUMAN | 93/4.5 | 77/5.11 | 11.60 | 8 | |

| Protein OS-9 | Q13438 | OS9_HUMAN | 93/4.5 | 76/4.80 | 9.40 | 3 | |

The five protein spots [Fig.1B (a) and C] identified as being JDM-specific were individually digested with trypsin and were subjected to mass spectrometry. Twenty-two proteins from five protein spots were identified.

MS/MS: tandem mass spectrometry; MW: molecular weight.

Antibodies against chaperone or co-chaperone proteins identified in patients with JDM

Using pathway analysis, 17 of the 22 candidate target antigens for AECA in JDM were predicted to interact with chaperone proteins involved in antigen processing and presentation. Among the seven chaperone or co-chaperone proteins were HSC70, HSP 90-beta (HS90B) and stress-induced-phosphoprotein 1, a protein that mediates the association of HSC70 and HSP90. IgG autoantibodies to HSC70 were detected by ELISA in 23% of the patients with JDM (n = 39; Fig. 1D). However, 50% of the untreated JDM patients with active disease (n = 10) had anti-HSC70 antibodies, in contrast to 7% (P < 0.05) of the patients with JIA (n = 15) and 5% (P < 0.01) of control children (n = 20). Among treated patients with active disease (n = 15), 13% had detectable anti-HSC70 antibodies, while 14% of the patients with inactive disease (n = 14) had detectable anti-HSC70 antibodies. The frequency of anti-HSC70 antibodies shown was not significantly different with regard to age or sex. On the other hand, IgG autoantibodies to HS90B were detected in 6% of the patients with JDM (n = 31) and IgG autoantibodies to stress-induced-phosphoprotein 1 were not detected patients with JDM (data not shown).

Discussion

Despite the prominence of the vascular features of JDM, few investigations have focused on this aspect of the pathobiology of the disease. Thus, the question of how and why blood vessels within the skin and musculature (and other sites) of patients with JDM become targets of immune attack remains unanswered.

In the current paper, we used a proteomic approach to address this question. Specifically, we asked whether endothelial cells might be targets of autoantibodies, a plausible hypothesis given that at least one study has demonstrated the presence of both IgG and complement proteins within the vessel walls of children with JDM [8], although a recent study has not duplicated this finding [9]. We found that a broad spectrum of AECA could be identified in plasma samples from children with JDM (Table 1). These antibodies were more commonly found in children with active, untreated JDM and were rare in children with polyarticular-onset JIA.

These antibodies were not randomly directed toward cell-surface proteins, but seemed to be directed toward proteins involved in antigen processing and stress response (e.g. HSC70). This finding suggests that at least some AECA may play a regulatory role, modifying the processing of antigens, long recognized as an important function of endothelium [10]. In support of a regulatory role for the autoantibodies are the findings of De Paep et al. [11], who reported that, in inflammatory myopathies in adults, HSP70, an homologous protein, is expressed in injured muscle fibers and may be involved in muscle repair and regeneration. This finding is consistent with the report by Mišunová et al. [12] demonstrating increased levels of HSP70 proteins in serum of adult patients with inflammatory myopathies. Thus, it is possible that the presence of HSC70 antibodies is a response to damaged muscle fiber rather than a primary mechanism of injury. A growing body of evidence supports the idea that type-1 IFN-induced muscle damage may be the primary mechanism of JDM [13, 14].

Rider et al. have shown that specific autoantibodies in childhood inflammatory myopathies are associated with distinct clinical phenotypes, disease complications and/or clinical outcomes. Our patient numbers are too small to determine whether such associations exist for AECA in JDM, and our patient population was homogeneous compared with the broad clinical spectrum of childhood inflammatory myopathies [1]. Studies of a larger, clinically heterogeneous population will be required to determine whether there are associations between AECA and specific clinical phenotypes or outcomes.

Our data suggest that antibodies against HSC70, which was one of the antigens identified by mass spectrometry, might be a useful diagnostic biomarker. The autoantigens we identified in JDM did not overlap with what we have seen in systemic vasculitis using a similar approach [5]. There are also reports of autoantigens for AECA in patients with SLE [15–17]. Autoantibodies against HSP family proteins such as HSP60 [15] and HSP90 [16], but not HSP70 [16], were detected by ELISA in SLE. Using ELISA assays, we identified anti-HSC70 in 5 of the 10 samples of children with newly diagnosed, untreated JDM and in fewer than 5% of children with polyarticular JIA. If these findings are corroborated in a larger cohort of patients, anti-HSC70 would have significantly better specificity than other screening tests commonly used in primary care settings, for example, ANA [18].

In conclusion, we have demonstrated the presence of a broad spectrum of previously unrecognized AECA in children with JDM. Larger studies are needed to determine the clinical significance of these antibodies and/or their utility and diagnostic or prognostic biomarkers.

Funding: This work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI Grant Number JP16K10045. This work was also supported by R01-AR060604 from the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure statement: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Shah M, Mamyrova G, Targoff IN. et al. The clinical phenotypes of idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Medicine 2013;92:25–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Crowe WE, Bove KE, Levinson JE, Hilton PK.. Clinical and pathogenetic implications of histopathology in childhood polydermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum 1982;25:126–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Banker BQ, Victor M.. Dermatomyositis (systemic angiopathy) of childhood. Medicine 1966;45:261–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rider LG, Shah M, Mamyrova G. et al. The myositis autoantibody phenotypes of juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Medicine (Baltimore) 2013;92:223–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Karasawa R, Kurokawa MS, Yudoh K. et al. Peroxiredoxin 2 is a novel autoantigen for anti-endothelial cell antibodies in systemic vasculitis. Clin Exp Immunol 2010;161:459–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Karasawa R, Fujieda M, Ohta K, Yudoh K.. Validation of a new biomarker in patients with Kawasaki Disease identified by proteomics. J Data Mining Genomics Proteomics 2013;4:1. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wallace CA, Huang B, Bandeira M, Ravelli A, Giannini EH.. Patterns of clinical remission in select categories of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:3554–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Whitaker JN, Engle WK.. Vascular deposits of immunoglobulin and complement in idiopathic inflammatory myopathy. N Engl J Med 1972;286:333–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lahoria R, Selcen D, Engel AG.. Microvascular alterations and the role of complement in dermatomyositis. Brain 2016;139:1891–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Marelli-Berg FM, Jarmin SJ.. Antigen presentation by the endothelium: a green light for antigen-specific T cell trafficking? Immunol Lett 2004;93:109–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Paepe BD, Creus KK, Weis J, Bleecker JL.. Heat shock protein families 70 and 90 in Duchenne muscular dystrophy and inflammatory myopathy: balancing muscle production and destruction. Neuromuscul Disord 2012;22:26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mišunová M, Svitálková T, Pleštilová L. et al. Molecular markers of systemic autoimmune disorders: the expression of MHC-located HSP70 genes is significantly associated with autoimmunity development. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2017;35:33–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Baechler EC, Bauer JW, Slattery CA. et al. An interferon signature in the peripheral blood of dermatomyositis patients is associated with disease activity. Mol Med 2007;13:59–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Baechler EC, Bilgic H, Reed AM.. Type I interferon pathway in adult and juvenile dermatomyositis. Arthritis Res Ther 2011;13:249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dieudé M, Senécal JL, Raymond Y.. Induction of endothelial cell apoptosis by heat-shock protein 60-reactive antibodies from anti-endothelial cell autoantibody-positive systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:3221–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Conroy SE, Faulds GB, Williams W, Latchman DS, Isenberg DA.. Detection of autoantibodies to the 90 kDa heat shock protein in systemic lupus erythematosus and other autoimmune diseases. Br J Rheumatol 1994;33:923–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shirai T, Fujii H, Ono M. et al. A novel autoantibody against fibronectin leucine-rich transmembrane protein 2 expressed on the endothelial cell surface identified by retroviral vector system in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther 2012;14:R157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McGhee JL, Kickingbird LM, Jarvis JN.. Clinical utility of antinuclear antibody tests in children. BMC Pediatr 2004;4:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]