See Lerche (doi:10.1093/brain/awy073) for a scientific commentary on this article.

PRRT2 mutations cause heterogeneous paroxysmal neurological disorders. Using iPSC-derived neurons from patients homozygous for a nonsense PRRT2 mutation and cortical neurons from PRRT2-knockout mice, Fruscione et al. show that PRRT2 is a negative modulator of voltage-dependent NaV1.2/1.6 channels. Increased neuronal excitability may contribute to the paroxysmal nature of PRRT2-linked diseases.

Keywords: proline-rich transmembrane protein 2, paroxysmal disorders, induced pluripotent stem cells, voltage-dependent sodium channels, neuronal excitability

Abstract

See Lerche (doi:10.1093/brain/awy073) for a scientific commentary on this article.

Proline-rich transmembrane protein 2 (PRRT2) is the causative gene for a heterogeneous group of familial paroxysmal neurological disorders that include seizures with onset in the first year of life (benign familial infantile seizures), paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia or a combination of both. Most of the PRRT2 mutations are loss-of-function leading to haploinsufficiency and 80% of the patients carry the same frameshift mutation (c.649dupC; p.Arg217Profs*8), which leads to a premature stop codon. To model the disease and dissect the physiological role of PRRT2, we studied the phenotype of neurons differentiated from induced pluripotent stem cells from previously described heterozygous and homozygous siblings carrying the c.649dupC mutation. Single-cell patch-clamp experiments on induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neurons from homozygous patients showed increased Na+ currents that were fully rescued by expression of wild-type PRRT2. Closely similar electrophysiological features were observed in primary neurons obtained from the recently characterized PRRT2 knockout mouse. This phenotype was associated with an increased length of the axon initial segment and with markedly augmented spontaneous and evoked firing and bursting activities evaluated, at the network level, by multi-electrode array electrophysiology. Using HEK-293 cells stably expressing Nav channel subtypes, we demonstrated that the expression of PRRT2 decreases the membrane exposure and Na+ current of Nav1.2/Nav1.6, but not Nav1.1, channels. Moreover, PRRT2 directly interacted with Nav1.2/Nav1.6 channels and induced a negative shift in the voltage-dependence of inactivation and a slow-down in the recovery from inactivation. In addition, by co-immunoprecipitation assays, we showed that the PRRT2-Nav interaction also occurs in brain tissue. The study demonstrates that the lack of PRRT2 leads to a hyperactivity of voltage-dependent Na+ channels in homozygous PRRT2 knockout human and mouse neurons and that, in addition to the reported synaptic functions, PRRT2 is an important negative modulator of Nav1.2 and Nav1.6 channels. Given the predominant paroxysmal character of PRRT2-linked diseases, the disturbance in cellular excitability by lack of negative modulation of Na+ channels appears as the key pathogenetic mechanism.

Introduction

PRRT2 is the causative gene for a clinical-genetic spectrum of paroxysmal neurological disorders (Chen et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2012). The most common manifestation of PRRT2 mutations are seizures with onset in the first year of life (benign familial infantile seizures), paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia or a combination of paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia and infantile convulsions, typically segregating as autosomal dominant traits with incomplete penetrance. In addition, about 5% of patients display other disorders, such as episodic ataxia and hemiplegic migraine (Heron and Dibbens, 2013; Ebrahimi-Fakhari et al., 2015; Gardiner et al., 2015; Valtorta et al., 2016). Interestingly, all these diseases are paroxysmal in nature, suggesting the presence of common pathophysiological mechanisms. In addition to being the major gene mutated in benign familial infantile seizures, paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia or paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia/infantile convulsions, PRRT2 accounts for the second highest number of epilepsy-associated mutations after SCN1A (Heron and Dibbens, 2013).

About 95% of the more than 70 different PRRT2 mutations reported to date are nonsense or frameshift. The majority of patients (≅80%) carry the same frameshift mutation (c.649dupC; p.Arg217Profs*8) that leads to a premature stop codon, generating an unstable mRNA or a truncated protein, which is degraded. Therefore, most of the PRRT2 mutations are predicted to be loss-of-function leading to haploinsufficiency (Chen et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2016; Valtorta et al., 2016). The few patients bearing homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations in PRRT2 show a more severe phenotype with paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia, prolonged ataxia attacks, seizures and intellectual disability (Labate et al., 2012; Delcourt et al., 2015).

PRRT2 is highly expressed in the brain, peaking in regions such as neocortex, hippocampus, basal ganglia and cerebellum that are implicated in the clinical manifestations of PRRT2-linked diseases (Valente et al., 2016a; Michetti et al., 2017a). Acute PRRT2 silencing in primary mouse neurons revealed a marked deficit in the density and strength of excitatory synapses, indicating an important role of the protein in coupling Ca2+ sensing to synaptic vesicle fusion (Valente et al., 2016a). Interestingly, the recently characterized PRRT2 knockout (KO) mouse recapitulates many of the phenotypic features of the human PRRT2-linked disorders, showing paroxysmal movements appearing soon after birth and a dyskinetic/epileptic phenotype in response to sensory stimuli (Michetti et al., 2017a). The episodic nature of these events suggests that they result from network instability and/or hyperexcitability (Michetti et al., 2017b).

In an attempt to understand the molecular basis of the PRRT2-associated diseases, we investigated the physiological properties of human neurons differentiated from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) of previously described heterozygous and homozygous siblings carrying the common PRRT2 mutation c.649dupC (Labate et al., 2012). We found that homozygous iPSC-derived human neurons showed significant increases in voltage-dependent Na+ current and intrinsic excitability that were both rescued by reintroduction of the human wild-type PRRT2. The same phenotype was shared by primary cortical neurons from the PRRT2-KO mouse that also displayed increased Na+ current and heightened spontaneous and evoked electrical activity at single cell and network levels. We demonstrate that PRRT2 directly interacts with the voltage-gated Na+ channels Nav1.2 and Nav1.6, but not Nav1.1, and significantly decreases their membrane exposure and Na+ current. The study demonstrates that PRRT2 is an important negative modulator of Nav1.2 and Nav1.6 channels and that the lack of PRRT2 leads to Na+ channel hyperactivity in human and mouse neurons.

Materials and methods

Materials and standard procedures

PRRT2-KO mice were generated by EUCOMM/KOMP using a targeting strategy based on the ‘knockout-first’ allele (Skarnes et al., 2011; Michetti et al., 2017a). Mutant animals in a C57BL/6N background were propagated as heterozygous colonies in the IIT SPF facility. All experiments were carried out in accordance with the guidelines established by the European Communities Council (Directive 2010/63/EU of 4 March 2014) and were approved by the Italian Ministry of Health (authorization n. 73/2014-PR and n. 1276/2015-PR). The plasmids used in the study are detailed in the Supplementary material. The standard procedures quantitative reverse transcription-PCR, western blotting, cell culture procedures, immunocytochemistry, pull-down and co-immunoprecipitation assays, surface biotinylation and synaptopHluorin assays are reported in detail in the Supplementary material.

Generation of iPSC clones and differentiation into neurons

IPSCs were generated from dermal fibroblasts of three siblings of a consanguineous family segregating the common PRRT2 mutation c.649dupC. Skin biopsies were performed upon informed consent at the Department of Medical Sciences, Institute of Neurology, University ‘Magna Graecia’, Catanzaro, Italy using the punch biopsy procedure and fibroblasts were cultured in RPMI (Gibco) supplemented with 20% (v/v) foetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. For control iPSC lines (FF0201992 and FF0631984), fibroblasts of age-matched normal male donors were obtained from the ‘Cell Line and DNA Biobank from Patients affected by Genetic Diseases’ (Istituto G. Gaslini, Genova, Italy), which is a member of the Telethon Network of Genetic Biobanks (project no. GTB12001). The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the G. Gaslini Institute. DNA genotyping and analysis of copy number variations were performed on genomic DNA extracted from cultured fibroblasts and iPSC lines as detailed in the Supplementary material. To obtain terminally differentiated neurons, neural precursor cells (NPCs), transduced with green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing lentiviruses, were grown in co-culture with embryonic Day 18 rat primary cortical neurons for 25–45 days following previously described protocols (Shi et al., 2012; Wen et al., 2014). The detailed procedures are reported in the Supplementary material.

Patch-clamp and multielectrode array electrophysiology

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were made as previously described (Valente et al., 2016b) and are reported in detail in the Supplementary material. For recording the spontaneous and evoked electrical activity of primary cortical networks, neurons were plated onto planar multi-well multielectrode arrays (MEAs). The MEA plates used (768-GL1-30Au200 from Axion BioSystems) were composed of 12 wells, each containing a square grid of 64 nanoporous gold electrodes (30 μm electrode diameter; 200 μm centre-to-centre spacing), which created a 1.43 × 1.43 mm recording area. Further details are reported in the Supplementary material.

Analysis of the axon initial segment

Immunofluorescence of the axon initial segment (AIS) of cultured cortical neurons was performed as previously described (Valente et al., 2016b). For the morphological identification of the AIS in mouse neurons in excitatory neurons, cells were fixed at in vitro Day (DIV) 16 and probed with anti-GAD65, anti-PanNav and anti-AnkyrinG antibodies. To quantify the immunofluorescence intensity at the AIS of GAD65-negative excitatory neurons, images of cultured neurons were acquired with a Leica SP8 confocal microscope using a 63× oil objective and 1024 × 1024 pixels (1 pixel = 0.24 µm) in z-stack with 0.3 µm steps. To analyse stack images, a Matlab script freely available at: www.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/28181-ais-quantification was used as previously described (Grubb and Burrone, 2010; Valente et al., 2016b). Briefly, a line profile was drawn along the fluorescently labelled AIS from the soma through, and 5 µm past, the AIS. Pixel fluorescence intensity values were averaged over a 3 × 3 pixel square centred on an arbitrarily drawn line, which was then smoothened using a 40-point sliding mean and normalized between 1 and 0 (maximum and minimum fluorescence intensity). The maximum position of the AIS was determined where the smoothed and normalized profile of fluorescence intensity reached its peak. The start and end positions of the AIS were the proximal and distal sites, respectively, at which the profile dipped to 33% of its peak. The distance of the start, maximum and end positions of the AIS from the soma were measured, as the distance from the point where the neuronal process forming the axon had a diameter lower than 2 µm, as visualized by transmitted light. For the analysis of AIS in iPSC-derived neurons, cells were fixed at 30 days of differentiation and probed with anti-PanNav and anti-AnkyrinG antibodies. To quantify the immunofluorescence intensity at the AIS of GFP+ neurons, images were acquired in wide-field with an Olympus BX41 epifluorescence microscope using a 40×/0.75 objective and analysed as described above.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were replicated at least three times and were blinded to the experimenters. Data are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM) for number of independently differentiated clones (n) or mouse preparations as detailed in the figure legends. Normal distribution of data was assessed using the D’Agostino-Pearson’s normality test. The F-test was used to compare variance between two sample groups. To compare two normally distributed sample groups, the Student’s unpaired or paired two-tailed t-test was used. To compare two sample groups that were not normally distributed, the non-parametric Mann-Whitney’s U-test was used. To compare more than two normally distributed sample groups, one-way ANOVA, followed by post hoc multiple comparison tests was used. Alpha levels for all tests were 0.05% (95% confidence intervals). Statistical analysis was carried out using OriginPro-8 (OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA, USA) and Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc.) software.

Results

Generation and characterization of iPSC-derived neurons from fibroblasts of patients carrying the PRRT2 c.649dupC mutation

To study the effects of PRRT2 mutations in human neurons, we generated iPSC lines from fibroblasts of patients belonging to a consanguineous Italian family (Labate et al., 2012) (pedigree in Supplementary Fig. 1A) carrying the common c.649dupC mutation in heterozygosity (Patient P1) or homozygosity (Patients P2 and P3, siblings of Patient P1) and of sex- and age-matched normal donors (control Subjects C1 and C2). Patient P1 manifested only transitory infantile seizures, whereas Patients P2 and P3 presented a more severe phenotype with absences, paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia, episodic ataxia and intellectual disability. IPSC lines were generated by using Sendai virus-mediated expression of the four Yamanaka’s factors (see ‘Materials and methods’ section). The clinical features of the patients, the number and identification codes of the iPSC clones are detailed in Supplementary Fig. 1B. A standardized quality control procedure was performed on iPSCs by qRT-PCR (Supplementary Fig. 1C) and immunofluorescence analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1D–F) to confirm the expression of pluripotent stem cell markers. Moreover, gaining of pluripotency was confirmed in vitro by showing iPSC ability to differentiate into cells of the three germ layers (Supplementary Fig. 1G–I). Sanger sequencing confirmed the presence of the c.649dupC mutation in both heterozygous and homozygous iPSC lines and array-CGH analysis showed the absence of genomic rearrangements in all iPSC clones (Supplementary Fig. 2)

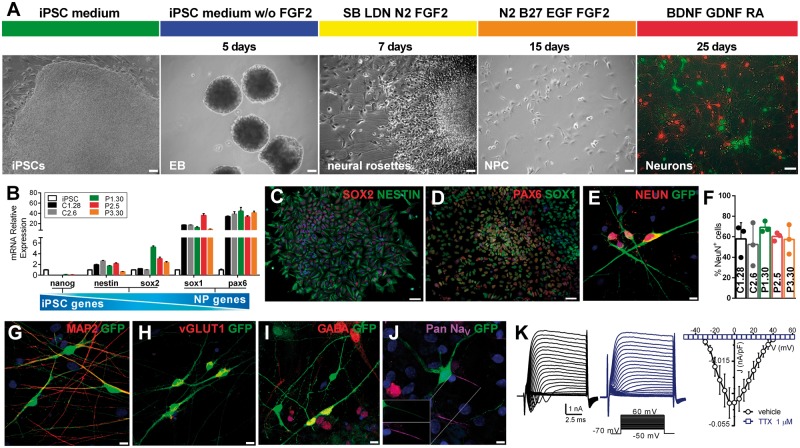

IPSCs were differentiated into a stable population of self-renewable NPCs through the formation of free-floating embryoid bodies and of adherent neural rosettes in the presence of inhibitors of the BMP and TGFβ pathways (Fig. 1A). Gene expression profiling showed that NPC markers were upregulated in all NPC populations with respect to the parental iPSCs, whereas pluripotency-specific genes were downregulated (Fig. 1B). Moreover, immunofluorescence analysis showed that NPCs were positive for the neural cell markers SOX2, NESTIN, SOX1 and the dorsal telencephalic marker PAX6, indicating a cortical progenitor fate (Fig. 1C and D).

Figure 1.

Neuronal differentiation and characterization of iPSC-derived neurons of patients carrying the c.649dupC mutation in PRRT2. (A) Overview of the neuronal differentiation protocol and representative images at different stages. From left to right: iPSC colony, embryoid bodies (EBs), neural rosettes, NPCs and live image of iPSC-derived neurons (green, GFP+) in co-culture with cortical rat neurons (red, TdTomato+). Scale bar = 50 µm. (B) NPC gene expression profile by qRT-PCR. NPC-specific markers SOX1 and PAX6 are upregulated in NPCs, as compared to iPSCs. NESTIN and SOX2, which participate in self-renewal and neural differentiation, are expressed by both cell types. The pluripotency-specific gene NANOG is markedly downregulated in NPCs. Data are means ± SEM of relative expression using iPSC as reference. (C and D) Representative immunofluorescence images showing expression of NPCs markers in neural rosettes. Scale bar = 50 µm. (E–G) Representative immunofluorescence images of the mature neuronal markers NEUN (E; quantified in F) and MAP2 (G) in iPSC-derived neurons after 4 weeks of differentiation. Scale bar = 10 µm. In F, data are expressed as means ± standard deviation of n = 3 independent experiments (at least 50 cells each experiment). One clone for each genotype is shown. Not significant, Kruskal-Wallis/Dunn’s test. (H and I) Representative immunofluorescence of VGLUT1- and GABA-positive cells. Scale bar = 10 µm. (J) Representative immunofluorescence of iPSC-derived neurons expressing voltage-gated Na+ channels. The inset shows co-localization of GFP and PanNav at the AIS. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Scale bar = 5 µm. (K) Left: Representative whole-cell currents obtained by depolarizing C1.28 neurons with a family of 10-ms depolarizing voltage steps (inset) in the absence (black) or presence of TTX (1 µm; blue). Right: Current density versus voltage relationship for C1.28 neurons alternatively exposed to either vehicle or TTX (1 µm; n = 9). Peak amplitudes were normalized to the cell capacitance to obtain current densities.

To obtain mature functional neurons, NPCs transduced with GFP were co-cultured with embryonic rat cortical neurons in the presence of BDNF, GDNF and retinoic acid (Fig. 1A). After 4–5 weeks of differentiation, iPSC-derived neurons from both controls and patients reached a mature state with neuron-like morphology and formed a complex and extended network expressing mature neuronal markers, with percentages of NEUN-positive cells that did not differ among control, heterozygous or homozygous PRRT2 genotypes (Fig. 1E–G). IPSC-derived neurons expressed VGLUT1 or GABA (Fig. 1H and I), indicating the formation of a mixed network of excitatory and inhibitory neurons. Moreover, human neurons of all genotypes expressed α-subunits of voltage-gated Na+ (Nav) channels at the AIS (Fig. 1J).

IPSC-derived neurons consistently displayed voltage-dependent inward and sustained outward currents. Inward currents peaked at −5/0 mV and were completely abolished by tetrodotoxin (TTX), representing bona fide Na+ currents (Fig. 1K). IPSC-derived neurons also formed active synaptic connections responding to electrical stimulation with Ca2+-dependent activation of exo-endocytosis of synaptic vesicles (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Homozygous iPSC-derived neurons display increased Na+ current densities and intrinsic hyperexcitability

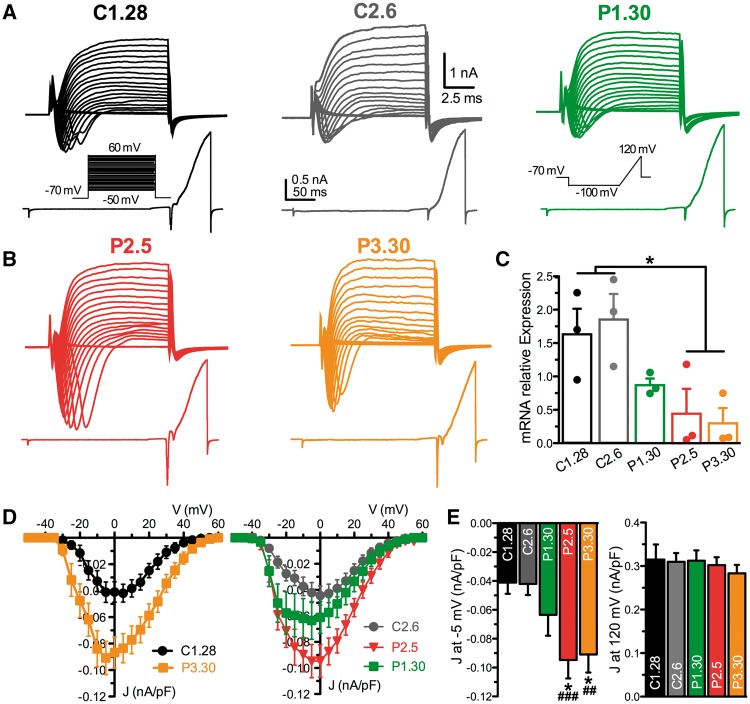

Next, we started the physiological characterization of neurons derived from the heterozygous Patient P1 (P1.30), the two homozygous Patients P2 and P3 (P2.5 and P3.30) and the two healthy control Subjects C1 and C2 (C1.28 and C2.6). Single-cell neuronal excitability was analysed by measuring the macroscopic inward and outward currents evoked by constant current pulses of increasing amplitude and ramp stimulations, respectively, in the voltage-clamp configuration (Fig. 2A and B). The analysis of PRRT2 mRNA expression by qRT-PCR in the differentiated neuronal preparations showed that the homozygous clones had very low levels of PRRT2 mRNA with respect to the healthy controls, while the heterozygous clone expressed intermediate levels (Fig. 2C). Interestingly, both homozygous clones displayed greatly increased fast-inactivating inward currents in response to step and ramp stimulations, while the outward currents were comparable across phenotypes (Fig. 2A and B). An increase of the inward current density (J; nA/pF), not associated with any shift in the J/V relationship, was present in homozygous neurons (Fig. 2D). The increase of J at −5 mV in either homozygous clone was significantly higher than that recorded in either control clone, as well as in the heterozygous clone, which was not significantly different from controls (Fig. 2E, left). No significant differences were observed in the outward J measured at 120 mV across genotypes (Fig. 2E, right). The same effects were replicated by recording neurons derived from different iPSC clones of the same individuals (control Subjects C1.25 and C1.32, Patients P1.35 and P2.18), with a significant increase in inward J in homozygous, but not heterozygous, neurons with respect to control neurons and no effects on the outward J (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Figure 2.

Homozygous iPSC-derived neurons show an increased inward current density. (A and B) Representative whole-cell current families recorded from C1.28, C2.6 and P1.30 (A; from controls and heterozygous Patient 1, respectively) and from P2.5 and P3.30 clones (B; from homozygous Patients 2 and 3). Currents were elicited using a family of depolarizing 10 ms-voltage steps (top) or a ramp protocol (bottom). In both protocols (inset) cells were clamped at −70 mV before stimulation. (C) PRRT2 mRNA expression assessed by qRT-PCR in iPSC-derived neurons after 25 days of differentiation. Results are expressed as means ± SEM of n = 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05; Kruskal-Wallis/Dunn’s tests. (D) Current density versus voltage relationship for C1.28 and P3.30 (left) and C2.6, P2.5 and P1.30 (right) iPSC-derived neurons, calculated using the voltage step protocol shown in A. Neurons were grouped in two distinct panels for clarity. (E) Statistical analysis of the current density at −5 mV (left) and at 120 mV (right) for all iPSC-derived neurons reported in D. The current density at 120 mV was studied by the ramp protocol represented in A. Data are shown as means ± SEM (n = 20 for C1.28, n = 34 for C2.6, n = 29 for P1.30, n = 32 for P2.5 and n = 19 for P3.30). *P < 0.05 versus C1.28, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 versus C2.6; Kruskal-Wallis/Dunn’s tests.

To ascertain that the increased inward currents were voltage-gated Na+ currents, these were isolated from contaminating outward K+ and inward Ca2+ currents by using internal and external solutions containing K+ and Ca2+ channel blockers and applying a prepulse protocol to avoid space-clamp artefacts (Supplementary Fig. 5; see ‘Materials and methods’ section). No significant changes in cell size, as evaluated by cell capacitance measurements, were observed between control and homozygous genotypes (C1.28 and P2.5; Supplementary Fig. 6A). The electrophysiological phenotype of iPSC-derived neurons was not associated with changes in the mRNA expression levels of the three main α1 subunits expressed by developing and mature neurons Nav1.1, Nav1.2 or Nav1.6 (Vacher et al., 2008; Supplementary Fig. 7A).

To verify whether the observed phenotypic changes were due to the lack of PRRT2 protein, its expression was rescued in the homozygous human neurons by infection with lentiviruses encoding Cherry-tagged human wild-type PRRT2 (Supplementary Fig. 8). P2.5-derived neurons were alternatively transduced with the PRRT2-Cherry or with the Cherry-alone virus as a control (mock), while control C1.28-derived neurons were only treated with the mock infection. Exogenous PRRT2 was correctly expressed in P2.5-derived neurons and the mRNA levels of PRRT2, determined by qRT-PCR, were greatly increased (Fig. 3A and B).

Figure 3.

Homozygous iPSC-derived neurons display an increased intrinsic excitability that is rescued by reintroduction of wild-type PRRT2. (A) Representative image of Cherry fluorescence reporting the expression of human PRRT2 in homozygous P2.5 neurons. Scale bar = 20 µm. (B) Expression of PRRT2 mRNA in mock-transduced C1.28 (black), mock-transduced P2.5 (red) and PRRT2-rescued P2.5 (blue) iPSC-derived neurons at 25 days of differentiation. Means ± SEM of n = 3 independent experiments. (C) Current density versus voltage relationship for the mock-transduced C1.28 and P2.5 iPSC-neurons and P2.5 neurons in which PRRT2 expression was rescued (P2.5+PRRT2). (D) Statistical analysis of the J at −5 mV (right) and at 120 mV for all conditions shown in C. Data are means ± SEM (n = 35 for C1.28, n = 31 for P2.5, n = 26 for P2.5+PRRT2). (E) Representative shapes of evoked action potentials recorded in mock-transduced C1.28 (black), mock-transduced P2.5 (red) and PRRT2-rescued P2.5 (blue) iPSC-derived neurons. (F) Amplitude, maximal voltage, maximal slope and width at 0 mV calculated for the first action potential evoked by minimal current injection in cells from all studied genotypes. Data are shown as means ± SEM (n = 28 for C1.28, n = 33 for P2.5, n = 19 for P2.5+PRRT2). (G–I) Representative current-clamp recordings of action potentials (G) evoked by the injections of 5 pA step current (1-s duration; protocol shown in the inset) in C1.28, P2.5 and P2.5+PRRT2 iPSC-neurons. The threshold voltage (H) and the instantaneous and mean and firing frequencies (I) are shown as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus mock-transfected C1.28; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 versus mock-transfected P2.5; Kruskal-Wallis/Dunn’s tests.

Electrophysiological analysis confirmed the marked 2-fold increase of Na+ current in the mock-transduced P2.5 neurons, whereas re-expression of wild-type PRRT2 not only normalized, but also decreased it with respect to the mock-transduced control (C1.28), suggesting the presence of a dose-dependent modulation of Nav channel activity (Fig. 3C and D).

Patch-clamp recordings in current-clamp configuration revealed that homozygous iPSC-derived neurons responded to the injection of a depolarizing current with an evoked firing of action potentials. Consistent with the observed increase in Na+ current, homozygous iPSC-neurons exhibited a decreased threshold for action potential generation and an increased amplitude, peak and maximal slope of the rising phase of the action potential (Fig. 3E, F and H). Moreover, the action potential half-width was unchanged, in agreement with the lack of genotype-dependent changes in the voltage-dependent outward current (Fig. 3E and F). All the above-mentioned parameters were fully normalized by re-expression of wild-type PRRT2 (Fig. 3F and H).

However, despite a trend to an increase, both the instantaneous and the mean firing frequencies did not significantly differ from control neurons (Fig. 3G and I), confirming that the Na+ current is not the only determinant of firing rate in these neurons. In contrast, re-expression of wild-type PRRT2 in homozygous neurons significantly decreased the evoked firing activity (Fig. 3I). Moreover, homozygous iPSC-derived neurons displayed a lower input resistance than control neurons that was mirrored by an increased rheobase (Supplementary Fig. 6B and C). Such an effect cannot be ascribed to the increased Na+ current, but is probably due to a higher passive K+ conductance in the absence of PRRT2 that correlates with the higher rheobase.

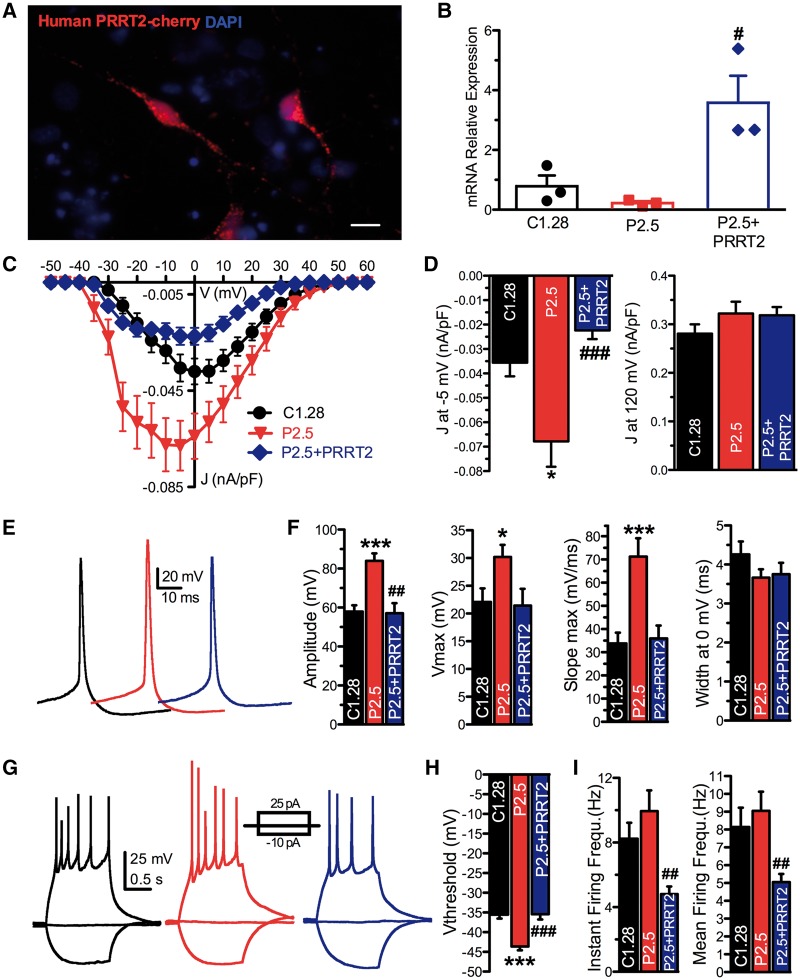

Mouse PRRT2-KO cortical excitatory neurons also display increased Na+ current densities and an extension of the axon initial segment

The results obtained in human neurons led us to investigate whether cortical excitatory neurons from the recently characterized PRRT2-KO mouse (Michetti et al., 2017a) also display an increase in intrinsic excitability. Using whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings, the Na+ currents evoked by constant current pulses were isolated by using intracellular and extracellular solutions to selectively block Ca2+ and K+ conductances (Fig. 4A). Space-clamp artefacts affecting the recordings of Na+ conductance were avoided using a prepulse protocol (see ‘Materials and methods’ section). Analysis of the overall JNa/V ratio revealed a significant increase in JNa in PRRT2-KO neurons that was not associated with voltage-dependent shifts (Fig. 4B). Similar results were obtained with the protocol used for iPSC-derived neurons (i.e. in the absence of the prepulse and with physiological internal and external solutions; Supplementary Fig. 9).

Figure 4.

Mouse PRRT2-KO excitatory cortical neurons display an increased intrinsic excitability associated with a distal shift of the axon initial segment. (A) Representative traces of somatic Na+ currents recorded from wild-type (black, WT) and PRRT2-KO (red) excitatory cortical neurons. (B) Current density versus voltage relationship for wild-type and PRRT2-KO excitatory cortical neurons. Means ± SEM (n = 20 for both conditions). (C and D) Recordings of spontaneous action potentials (C) and mean (±SEM) spontaneous firing frequency. (E and F) Representative current-clamp recordings of action potentials evoked by the current injection of 1-s step at 200 pA (E) and mean (±SEM) firing frequency (F) of wild-type (n = 56) and PRRT2-KO (n = 60) neurons. (G and H) Current-clamp recordings (G) showing action potentials activated by 20 current steps lasting 5 ms delivered at 80 Hz and mean (±SEM) probability to evoke action potentials at increasing stimulation frequencies (H) in wild-type (n = 59) and PRRT2-KO (n = 63) neurons. (I, left) Merged images of wild-type cortical neurons (16 DIV) immunostained for β-III tubulin (green), AnkyrinG (red) and PanNav (yellow). Scale bar = 25 μm. Middle: Magnification of the same neuron (white mark: axon hillock) and of the AnkyrinG fluorescence intensity profile used to measure the AIS start, end and maximum. The red line represents the threshold fluorescence used to define AIS limits. Right: Representative images of wild-type and PRRT2-KO cortical neurons immunostained for AnkyrinG (red) and PanNav (yellow). Cell bodies are circled. Scale bar = 20 μm. (J and K) Representative fluorescence intensity profiles of AnkyrinG (J) and PanNav (K) signals along the axon of wild-type (black) and PRRT2-KO (red) neurons. (L and M) Distance of AIS start, maximum and end from the cell body (L) and AIS length (M) in wild-type (black) and PRRT2-KO (red) neurons. Means ± SEM (n = 40 coverslips for both wild-type and PRRT2-KO from n = 3 independent experiments). In D, F, H, L and M: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; Mann-Whitney U-test.

The spontaneous firing rate of PRRT2-KO neurons, kept at the threshold (Vh = −40 mV) by injection of a constant depolarizing current, was significantly higher than that observed in wild-type neurons under the same conditions (Fig. 4C and D). Next, we depolarized the membrane potential with subsequent current steps to study the evoked firing. PRRT2-KO neurons showed a significantly higher evoked firing activity than wild-type neurons, as evaluated by mean firing rates (Fig. 4E and F). To evaluate the ability to adapt to increasing firing frequencies, we stimulated excitatory neurons with short (5 ms) supra-threshold current injection pulses administered at frequencies ranging from 10 to 120 Hz (Fig. 4G). Both wild-type and PRRT2-KO neurons were able to fire 100% of action potentials up to 40 Hz. However, at higher frequencies (80–120 Hz), wild-type neurons displayed a progressively increasing amount of failures, while PRRT2-KO neurons were characterized by a significantly higher probability of success (Fig. 4H).

Similar to homozygous iPSC-derived neurons, the observed changes in intrinsic excitability of PRRT2-KO neurons were not associated with changes in the expression levels of Nav1.1, Nav1.2 or Nav1.6 at both mRNA and protein levels (Supplementary Fig. 7B and C).

The increased evoked Na+ current density and the higher degree of intrinsic excitability suggested that PRRT2 deletion could affect the Na+ channel localization in the AIS, the action potential trigger zone where Na+ channels localize and their accumulation affects the action potential threshold (Garrido et al., 2003; Pan et al., 2006; Kole and Stuart, 2008; Grubb and Burrone, 2010). To this aim, wild-type and PRRT2-KO cortical excitatory neurons were immunostained with AnkyrinG and PanNav antibodies and the intensity profiles of both markers were analysed as a function of the distance from the cell body (Fig. 4I; see ‘Materials and methods’ section). Interestingly, no genotype-specific differences were detected in the AIS start and peak, while a significantly more distant AIS end was found in PRRT2-KO neurons, as evaluated from both AnkyrinG and PanNav immunoreactivities (Fig. 4J–L). This demonstrates a significantly increased length of the AIS in mutant neurons (Fig. 4M), consistent with the increased Na+ current density and intrinsic excitability.

To check whether a change in AIS was also present in human neurons, we quantified AIS length and position in control and homozygous iPSC-derived neurons. While homozygous neurons displayed a substantially preserved overall AIS length, their AIS was closer to the cell body with respect control neurons, with a significant decrease in the distance from the cell body of the AIS start and peak (Supplementary Fig. 10).

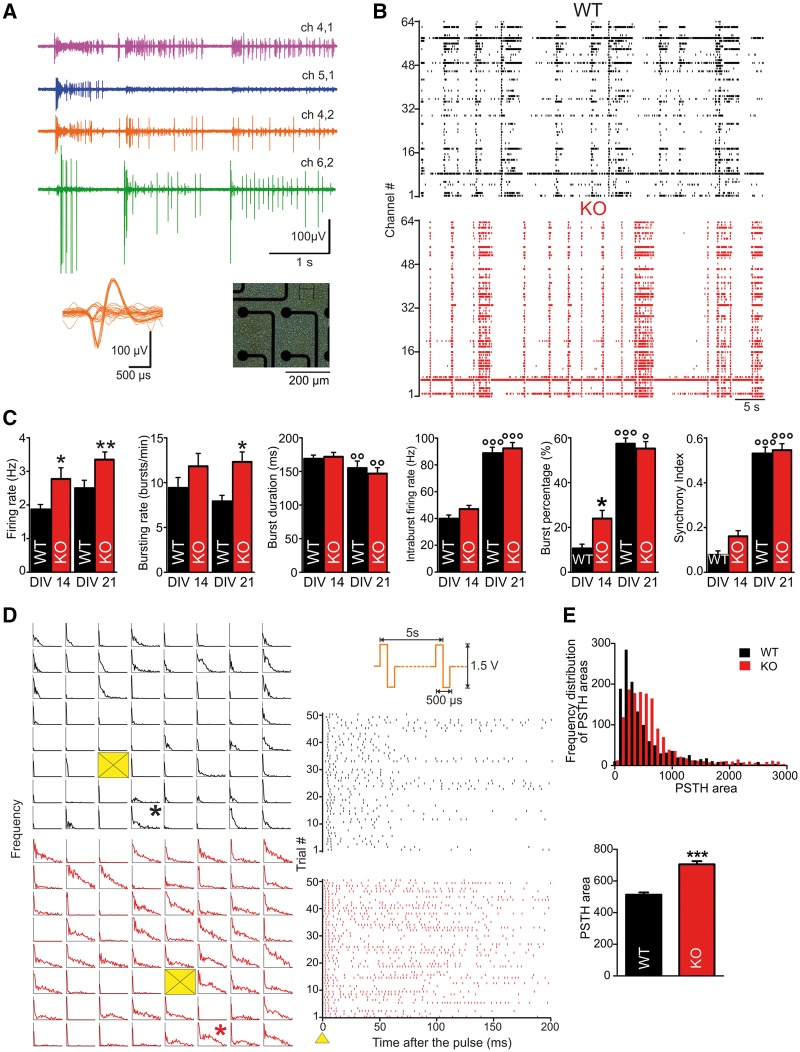

Mouse PRRT2-KO cortical networks display intense synchronization in collective bursting events

Primary cortical cultures obtained from PRRT2-KO and wild-type embryos were plated at high density onto MEA chips (Fig. 5A) and monitored over two sequential developmental windows: one in which synaptogenesis is still ongoing (14 DIV) and a second period in which mature connections are established (21 DIV). Figure 5B shows the raster plots of the spiking activity recorded over 60 s from representative wild-type and PRRT2-KO networks. For both genotypes, basal activity was characterized by the occurrence of isolated spikes, single-channel bursts and periodic collective events called ‘network bursts’ (Supplementary Fig. 11) in which single-channel activity was highly synchronized over a period that could last from a few hundreds of milliseconds up to 1 s (Van Pelt et al., 2004). As previously reported (Van Pelt et al., 2004; Chiappalone et al., 2006), the main activity parameters varied along development: while firing rate, intraburst firing rate, burst percentage (i.e. the fraction of total spikes within bursts) and global synchrony increased with age, burst duration decreased and bursting rate reached a stable plateau already at 2 weeks in vitro (Fig. 5C). PRRT2-KO networks displayed a similar maturation of activity parameters, although some genotype-specific differences were present. The firing rate was significantly higher for PRRT2-KO cultures at all stages of development. Moreover, a higher proportion of spikes were contained in bursts in PRRT2-KO cultures at 14 DIV, with an increased bursting rate that became significant at the later time point (Fig. 5C). Network-wide bursting activity was also measured at the mature stage (21 DIV; Supplementary Fig. 11A and B). The average network-bursting rate was markedly higher in PRRT2-KO than in wild-type networks. While the number of spikes per network burst was not affected, the duration of such events was consistently lower in the mutants, resulting in a higher intraburst firing rate. Moreover, PRRT2-KO networks reached a significantly higher instantaneous frequency in network bursts compared to wild-type ones, while the latency to the peak was similar between the two genotypes (Supplementary Fig. 11C and D). These data are consistent with the observation of an enhanced intrinsic excitability of PRRT2-KO cortical networks and their increased ability of sustaining high frequency firing, as shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5.

PRRT2-KO cortical networks display heightened excitability under basal conditions and in response to electrical stimulation. (A) Right: Phase contrast micrograph of wild-type (WT) cortical neurons on MEA. Left: Electrophysiological activity from four adjacent microelectrodes and spike waveforms extracted from one of the channels (right inset). (B) Raster plots of spiking activity recorded over 60 s from wild-type (top) and PRRT2-KO (bottom) cultures at 14 DIV. Each bar denotes a spike, each line an electrode. (C) Main firing and bursting parameters measured for wild-type (black) and PRRT2-KO (red bars) cultures at 14 and 21 DIV. Data are plotted as means ± SEM. n = 4 preparations for each genotype and developmental stage; 44 independent experiments for wild-type, 46 for PRRT2-KO. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 for wild-type versus age-matched PRRT2-KO cultures; °°P < 0.01; °°°P < 0.001 for 14 versus 21 DIV within each genotype; two-way ANOVA/Bonferroni’s or Kruskal-Wallis/Dunn's tests. (D) Left: PSTH maps showing the impulse response to the electrical stimulation for each site of representative wild-type and PRRT2-KO preparations, for 200 ms after stimulation. Yellow boxes indicate the stimulating sites. Right: Raster plots of evoked spiking recorded from the electrodes marked in the maps with an asterisk over a single stimulation session (i.e. 50 stimuli at 0.2 Hz). As shown in the top panel, pulses are biphasic with 1.5 V amplitude and 500 μs duration. (E) Top: Frequency distribution of the areas under the PSTHs generated from each channel of the dataset (black bars for wild-type, red bars for PRRT2-KO). Bottom: Mean (±SEM) PSTH area for wild-type and PRRT2-KO. n = 4 preparations for each genotype; 23 independent cultures for wild-type and 28 for PRRT2-KO. ***P < 0.001; Mann-Whitney U-test.

To assess evoked activity, mature wild-type and PRRT2-KO cultures were challenged with localized extracellular stimulation with low-frequency trains (Chiappalone et al., 2009). The raster plots of firing activity show the spiking responses within a 200-ms time window of representative wild-type and PRRT2-KO channels (Fig. 5D, right). The changes in firing probability as a function of time were quantitatively evaluated by building peristimulus time histograms (PSTHs; Fig. 5D, left). With respect to wild-type networks, PRRT2-KO networks responded to focal stimulation with a similar latency, but exhibited a strikingly sustained elevation of the firing probability. The frequency distribution of the areas under the PSTHs revealed a skewed profile for wild-type networks, whereas the frequency profile of PRRT2-KO networks was shifted towards larger values. Further confirming the diffuse hyperexcitability of mutant networks, their mean PSTH area proved to be significantly higher than that of wild-type networks (Fig. 5E).

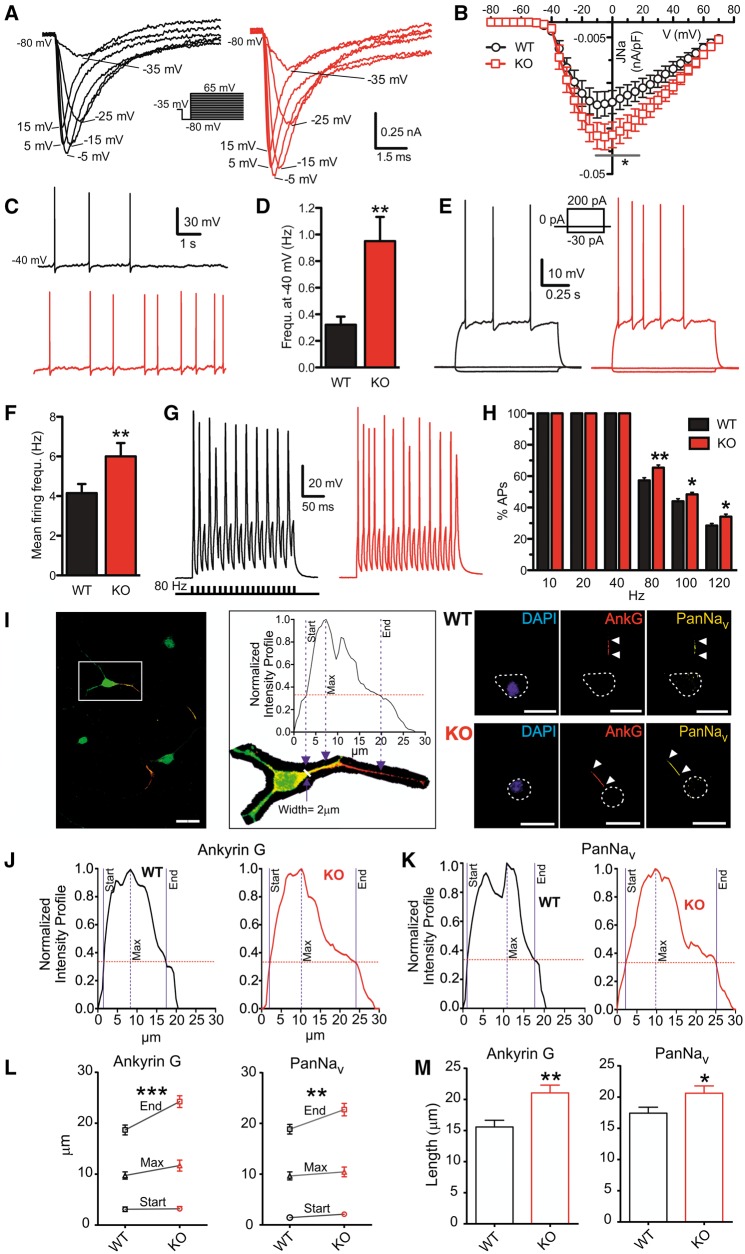

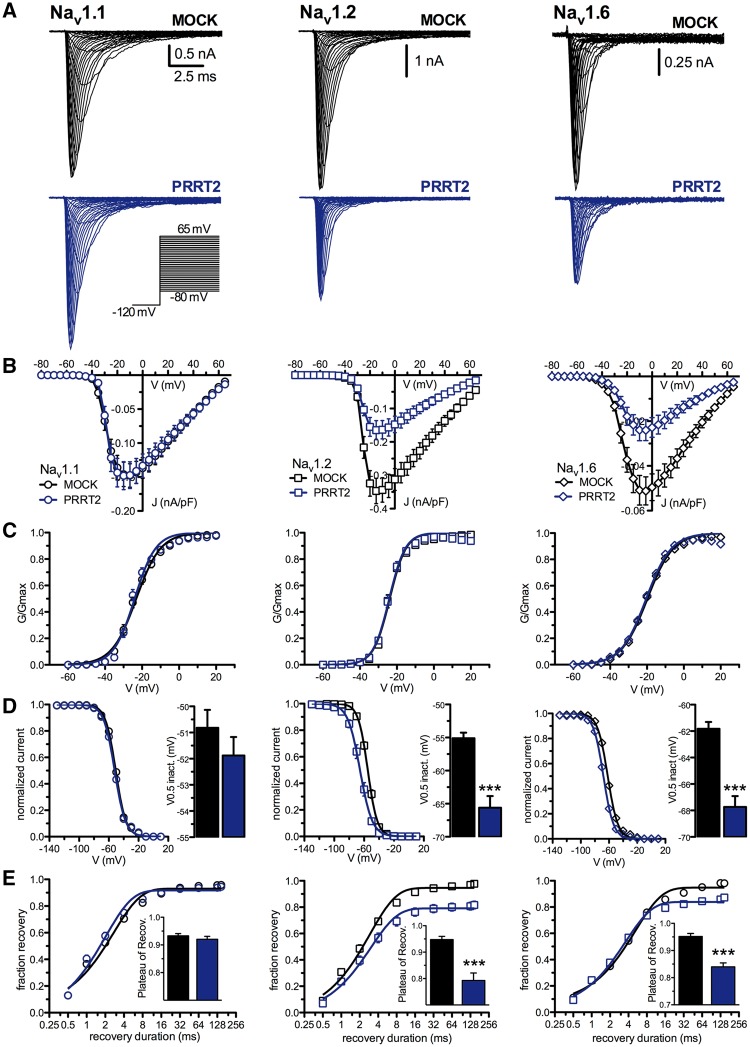

PRRT2 modulates Nav1.2, Nav1.6, but not Nav1.1, channel conductance when expressed in HEK-293 cells

To investigate the mechanisms that underlie the increase of Na+ current density, HEK-293 cells stably expressing Nav1.1, Nav1.2 or Nav1.6 channels were transfected with PRRT2 or control vector (mock). Strikingly, in the absence of channel inactivation (Vh = −120 mV), PRRT2 expression significantly reduced the Na+ current amplitude (Fig. 6A) and density (Fig. 6B) only in Nav1.2 and Nav1.6, but not in Nav1.1, expressing cell lines. The ≅50% decrease of current recorded in Nav1.2 and Nav1.6 channels in the presence of PRRT2 was not accompanied by any significant shift or slope change of the normalized conductance-voltage (G/Gmax-V) curves, suggesting that PRRT2 does not affect the voltage-dependent activation (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

PRRT2 expression decreases the Na+ current density of Nav1.2 and Nav1.6, but not of Nav1.1, expressed in HEK-293 cells. (A) Representative whole-cell currents recordings on clones stably expressing Nav1.1 (left), Nav1.2 (middle) and Nav1.6 (right) and transiently transfected with empty vector (MOCK, black) or PRRT2 (blue). Currents were evoked by 5-mV steps depolarization from −80 to 65 mV and cells were held at −120 mV (inset). (B) Current density versus voltage relationship for the genotypes described in A. (C) Voltage-dependence of activation for the three Nav channels co-expressed with MOCK or PRRT2. The lines are the best-fitted Boltzmann curves with the following mean values of half maximal voltage activation (V0.5) and slope (k): Nav1.1, MOCK, V0.5: −23.12 ± 0.27 mV, k: 6.58 ± 0.23 (n = 38), PRRT2 V0.5: −24.00 ± 0.24, k: 5.67 ± 0.21 (n = 34); Nav1.2, MOCK, V0.5: −23.89 ± 0.19 mV, k: 4.39 ± 0.16 (n = 22), PRRT2 V0.5: −24.16 ± 0.21; k: 4.37 ± 0.19 (n = 20); Nav1.6, MOCK, V0.5: −19.81 ± 0.14 mV, k: 6.99 ± 0.12 (n = 27), PRRT2 V0.5: −20.46 ± 0.17, k: 6.83 ± 0.15 (n = 29). (D) Steady-state inactivation curves for all conditions tested. The lines are the best-fitted Boltzmann curves and the half-maximal voltages for inactivation (V0.5 inact.) was graphed on the right. Data are means ± SEM (Nav1.1: MOCK, n = 36 and PRRT2; n = 30; Nav1.2: MOCK, n = 22 and PRRT2, n = 18; Nav1.6: MOCK, n = 24 and PRRT2, n = 21). (E) Time-dependent rate of recovery from inactivation. The plateau values (insets) were estimated from one-phase decay fit to the data. Data are means ± SEM (Nav1.1: MOCK, n = 33 and PRRT2; n = 24; Nav1.2: MOCK, n = 21 and PRRT2, n = 18; Nav1.6: MOCK, n = 20 and PRRT2, n = 18). In D and E: ***P < 0.001; unpaired Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U-test.

Despite the lack of effect on the voltage-dependence of activation, the voltage-dependence of fast inactivation was shifted to more negative potentials in the presence of PRRT2 in both Nav1.2 (10 mV negative shift) and Nav1.6 (6 mV negative shift), but again not in Nav1.1, expressing cell lines (Fig. 6D). The experimental data were entered in a detailed biophysical model of the Na+ current (Magistretti et al., 2006) to reproduce the unchanged activation curve and the leftward shift of the inactivation curve induced by PRRT2. Once the Na+ current was parametrized in the absence or presence of PRRT2, we found that the leftward shift of the inactivation curve could result in a delayed/incomplete recovery of the Na+ current from inactivation (Supplementary Fig. 12). Indeed, experimental recordings showed that Nav1.2 and Nav1.6, but not Nav1.1, were characterized by a slower recovery from inactivation in the presence of PRRT2 (Fig. 6E).

The results indicate that, when PRRT2 is co-expressed with Nav1.2 or Nav1.6, but not with Nav1.1, channels, a dramatic negative modulation of Na+ current density occurs. This effect is accompanied by changes in the voltage-dependence of inactivation and recovery from inactivation. This suggests that the PRRT2 is a negative modulator of both membrane expression and biophysical properties of Nav1.2 and Nav1.6 channels.

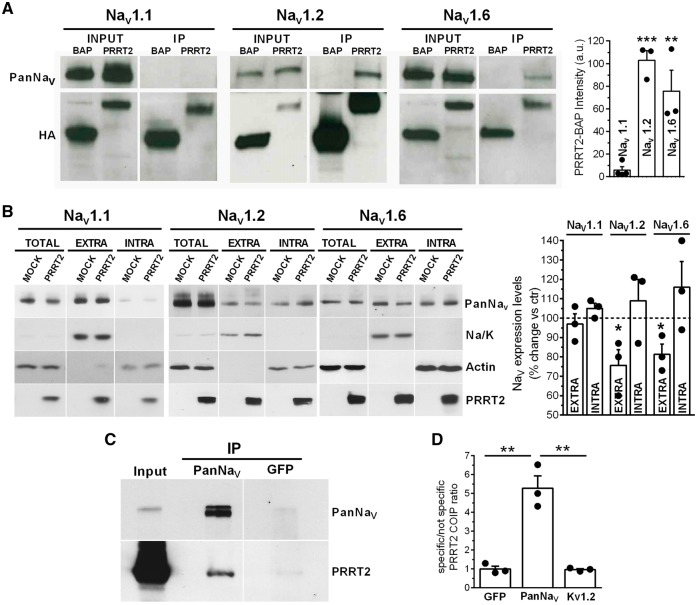

The specific interaction of PRRT2 with Nav1.2 and Nav1.6 modulates their surface expression

The electrophysiological phenotype of PRRT2-KO neurons and the significant effects of PRRT2 on Nav channels in HEK-293 cells point to a possible interaction between PRRT2 and the Nav1.2/ Nav1.6 α-subunits. To verify this possibility, either PRRT2 or the unrelated protein BAP was expressed in HEK-293 lines fused to the HA-tag, and the interactions with Nav channel subtypes were evaluated by pull-down assays. In full agreement with the subtype specificity of the electrophysiological data, PRRT2 specifically pulled down the Nav1.2 and Nav1.6 α-subunits, while the Nav1.1 subunit was not precipitated (Fig. 7A).

Figure 7.

PRRT2 interacts specifically with Nav1.2 and 1.6 and modulates their surface expression. (A) Left: Representative immunoblot of co-immunoprecipitation of Nav1.1, Nav1.2 and Nav1.6 by PRRT2. Either HA-tagged PRRT2 (PRRT2) or bacterial alkaline phosphatase (BAP) was expressed in HEK-293 cells expressing human Nav1.1, Nav1.2 or Nav1.6. Cells lysates (INPUT, 10 µg) and samples immunoprecipitated by anti-HA beads (IP) were analysed by western blotting with anti-PanNav and anti-HA antibodies. Right: Quantification of the PanNav signal in PRRT2 immunoprecipitates normalized to the BAP values. Means ± SEM of n = 3 independent experiments done in triplicates. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 versus Nav1.1; ANOVA/Dunnett’s tests versus Nav1.1. (B) Left: Representative immunoblots of cell surface biotinylation performed in HEK-293 cells expressing Nav1.1, Nav1.2 and Nav1.6 and transfected with PRRT2-HA or empty vector (MOCK). Total lysates (TOTAL), biotinylated (cell surface, EXTRA) and non-biotinylated (intracellular, INTRA) fractions were analysed by western blotting. Membranes were probed with antibodies to PanNav, PRRT2, Na/K-ATPase (Na/K) and actin, with the latter two antibodies used as markers of cell surface and intracellular fractions, respectively. Right: Cell surface and intracellular PanNav immunoreactivities are expressed in per cent of the respective MOCK value after normalization to Na/K-ATPase (for EXTRA fraction) and actin (for INTRA fraction). Means ± SEM of n = 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05; paired Student’s t-test. (C) Membrane extracts from the whole adult brain were used for immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-PanNav or anti-GFP control antibodies. Membranes were probed with anti-PanNav and anti-PRRT2 antibodies as indicated. Input, 50 µg. Vertical white lines in the blots indicate that the lanes were on the same gel, but have been repositioned in the figure. (D) Quantification of the PRRT2 signal in the samples immunoprecipitated with anti-PanNav, anti-GFP or anti-Kv1.2 antibodies, normalized to the anti-GFP control antibody. Means ± SEM of n = 3 independent experiments. **P < 0.01; one-way ANOVA/Bonferroni’s test.

The strong modulation of Na+ current density suggests that PRRT2 affects channel trafficking, membrane exposure and/or stability. To investigate this possibility, we performed a surface biotinylation assay in HEK-293 cell lines expressing the various Nav subtypes and transfected with either PRRT2-HA or an empty vector as control (Fig. 7B, left). While the total levels of each Nav α-subunit were not changed between mock- and PRRT2-transfected cells, the expression levels at cell surface of Nav1.2 and Nav1.6 were significantly decreased by PRRT2 with respect to control, with a parallel and quantitatively similar increase in the intracellular fraction (Fig. 7B, right). In contrast, Nav1.1 surface expression was virtually unaffected by PRRT2.

Finally, to assess the association between endogenous Nav channels and PRRT2 in vivo, we performed immunoprecipitation of Nav channels with anti-PanNav antibodies from detergent extracts of membrane fractions of wild-type mouse brain. Notably, endogenous PRRT2 was successfully co-immunoprecipitated with endogenous Nav channels from wild-type brain membranes, demonstrating that the interaction also occurs in the intact brain (Fig. 7C and D). Control antibodies directed to GFP or to voltage gated K+ channels 1.2 (Kv1.2) did not pull down any detectable PRRT2 immunoreactive signal (Fig. 7C, D and Supplementary Fig. 13A). The same assay, performed in extracts of PRRT2-KO mouse brain, did not reveal any cross-reactive band in the PRRT2 molecular mass range (Supplementary Fig. 13B).

These results demonstrate that PRRT2, by interacting with Nav1.2 and Nav1.6 channels, exerts a negative modulation on their membrane exposure. If the increase in JNa and excitability observed in PRRT2-deficient human and mouse neurons is attributable to a modulation of the membrane expression and biophysical properties of Nav1.2 and Nav1.6 channels, then a combination of the Nav 1.2/Nav 1.6 specific blockers should rescue the hyperexcitability of the PRRT2-KO neurons. Indeed, low concentrations of the Nav1.2/Nav1.6 selective channel blockers phrixotoxin-3 and 4,9-anhydrotetrodotoxin, respectively, were able to virtually abolish the differences in network bursting between wild-type and PRRT2-KO neurons (Supplementary Fig. 14).

Discussion

While the common heterozygous PRRT2 mutations are associated with relatively mild and pleiotropic phenotypes, the very rare homozygous mutations hitting both alleles are associated with severe syndromic forms recapitulating all the isolated paroxysmal phenotypes (Labate et al., 2012; Delcourt et al., 2015) that are mimicked by the recently described constitutive and conditional PRRT2-KO mouse (Michetti et al., 2017a; Tan et al., 2018). Here we report the successful development of a human model of PRRT2-linked diseases based on the generation of iPSC-derived neurons obtained from two rare homozygous and one heterozygous siblings for the most frequent PRRT2 mutation (Labate et al., 2012) and took the unique opportunity to compare the human knockout phenotype with the cellular and network phenotype of mouse cortical PRRT2-KO mouse neurons.

PRRT2 regulates cell and network excitability by interacting with Na+ channels

This study demonstrates that: (i) iPSC-derived neurons obtained from fibroblasts of two homozygous PRRT2 patients display increased Na+ currents and increased excitability; (ii) iPSC-derived neurons from the heterozygous sibling exhibit a trend to the same phenotype that parallels the milder clinical manifestations; (iii) the phenotype of homozygous iPSC-derived neurons is fully rescued by re-expression of human PRRT2; (iv) the cellular phenotype is to a large extent shared by cortical neurons from the PRRT2-KO mouse that display a marked hyperexcitability at the cell and network level; (v) PRRT2 is an important negative modulator of Nav1.2 and Nav1.6 channels, responsible for the generation of action potentials in excitatory neurons; (vi) PRRT2 does not affect Nav1.1 channels, responsible for the generation of action potentials in inhibitory neurons; and (vii) the interaction of PRRT2 with Na+ channels is also observed in brain tissue.

The closely similar phenotype of homozygous iPSC-derived neurons and mouse PRRT2-KO cortical neurons is noteworthy, pointing to a direct effect of PRRT2 absence that is not strongly affected by the genetic background. However, some differences exist, namely: (i) a trend for an increase in the evoked firing rate in homozygous iPSC-derived neurons, as compared to the significant increase in evoked firing of mouse PRRT2-KO neurons; and (ii) an AIS shift toward the cell body in the absence of length changes in homozygous iPSC-derived neurons, as compared to the significantly increased AIS length of mouse PRRT2-KO neurons.

Various experimental studies have demonstrated that while a change in Nav channel density directly affects the activation phase of the action potential shape, a similar direct relation does not necessarily exist between Nav channel density and evoked firing rate. Indeed, it was demonstrated (Kispersky et al., 2012) that a change in Nav channel density can associate with increases, decreases or no effect in the neuronal firing rate, depending on the specific pattern of passive conductances as well as of depolarization-activated outward conductances.

Changes in length and location of the AIS with respect to the cell body are known as an important form of structural/functional homeostatic plasticity (Grubb et al., 2011). In excitatory neurons, increased excitability in response to chronic activity deprivation was shown to be associated with either increased length or proximal shift of the AIS (Grubb and Burrone, 2010; Kuba et al., 2010). In this respect, the increase in AIS length observed in mouse PRRT2-KO neurons and the proximal shift observed in homozygous iPSC-derived neurons can represent distinct responses of mouse and human neurons to the absence of PRRT2, albeit both associated with increased excitability.

Two previous studies generated iPSC-derived neurons from PRRT2 patients. In the first study (Zhang et al., 2015), neurons differentiated from iPSCs derived from urinary cells of a single paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia patient bearing the same mutation of our study (c.649dupC) in heterozygosity did not exhibit any significant change in intrinsic excitability or current density of voltage-gated channels, in agreement with our findings. In the second study (Li et al., 2016), iPSC-derived neurons from patients heterozygous for distinct nonsense PRRT2 mutations (c.487C>T and c.573dupT) displayed a lower efficiency in stepwise neural induction and dysregulated transcriptome signatures regarding development and neurogenesis. Conversely, with the protocol used in this paper, neural precursors were differentiated to mature functional neurons with similar efficiency across genotypes.

Neuronal excitability is the product of integration of excitatory and inhibitory synaptic inputs at the AIS, where clusters of distinct Na+ channel subtypes generate action potentials (Kole et al., 2008). Interestingly, in excitatory neurons, the distal part of AIS presents abundant expression of Nav1.6, while the proximal part is enriched in Nav1.2, the same channel subtypes that are inhibited by PRRT2. In contrast, the Nav1.1 subtype, which is not affected by PRRT2, plays a major role in the AIS of inhibitory neurons (Ogiwara et al., 2007; Debanne et al., 2011; Catterall, 2014).

PRRT2 emerges as a novel negative modulator of Nav1.2 and Nav1.6 channel trafficking and function in human and mouse neurons, as demonstrated by the increased voltage-activated Na+ current, AIS changes and increased excitability observed in the absence of PRRT2. The main mechanism of the PRRT2-induced modulation of Nav channels consists in a decrease of their plasma membrane expression in favour of internalization. The PRRT2-mediated negative constraint to the membrane exposure of Nav1.2/Nav1.6 channels may also contribute to defining the AIS length and position, which depend on the amount of channels reaching the AnkyrinG-based scaffold at the axon hillock. Moreover, PRRT2 also affects the biophysical properties of Nav1.2/Nav1.6 channels by inducing a negative shift in the voltage-dependence of inactivation and a slow-down in the recovery from inactivation that decrease the percentage of Nav channels that can be activated under resting conditions.

PRRT2 has a multifunctional role in the CNS

Acute knockdown of PRRT2 in primary neurons gives rise to a marked impairment of fast synchronous neurotransmitter release due to a decrease in Ca2+ sensitivity. Indeed, PRRT2 has been reported to interact with components of the SNARE complex responsible for synaptic vesicle fusion and the fast Ca2+ sensor synaptotagmin (Valente et al., 2016a; Tan et al., 2018; Coleman et al., 2018). In addition, postsynaptic roles for PRRT2 in AMPA receptor signalling and in the formation/maintenance of postsynaptic spines have been hypothesized (Li et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2016). PRRT2 has a membrane-wide expression that is highest in axonal and synaptic domains (Lee et al., 2012; Valente et al., 2016a). Thus it is likely that, in addition to the reported role at the synapse, PRRT2 can interact with other membrane proteins governing neuronal excitability, such as ion channels. The interactions of PRRT2 with Na+ channels and their direct consequences on neuronal excitability not only provide a basis for the pathogenesis of the PRRT2-linked paroxysmal manifestations, but also indicate that PRRT2 could be a multifunctional protein, similarly to other presynaptic proteins, such as SNAP25 and synaptotagmin, that were recently demonstrated to play physiological roles distinct from neurotransmitter release (Tomasoni et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2017).

PRRT2 in the pathophysiology of paroxysmal disorders

The observed interactions of PRRT2 with Nav1.2/Nav1.6 channels, which are major regulators of the excitability of excitatory neurons, represent a plausible basis for the phenotype of PRRT2-linked disorders. Moreover, the lack of effects of PRRT2 on Nav1.1 channels, that is essential for the excitability of inhibitory neurons (Ogiwara et al., 2007), may enhance the excitation/inhibition unbalance triggering hypersynchronized activity in neuronal networks and behavioural paroxysms in patients.

Several considerations support the pathophysiological relevance of these findings. First, the behavioural phenotype of the PRRT2-KO mouse (Michetti et al., 2017a) closely resembles the paroxysmal phenotype of mice bearing mutations in voltage-dependent channels, such as the tottering and moonwalker mice (Matsushita et al., 2002; Becker et al., 2009). Second, a spectrum of epileptic and dyskinetic syndromes negative for PRRT2 mutations were found to be associated with gain-of-function mutations in the α-subunit of Nav1.6 channel (O'Brien et al., 2012; Gardella et al., 2016). Notably, the co-segregating heterozygous missense mutation (c.4447G>A) identified in 16 members of three families (Gardella et al., 2016) hits the inactivation gate of the Nav1.6 α-subunit, suggesting an impaired channel inactivation that is consistent with the observed effects of PRRT2 on the Nav1.6 channel. Moreover, mutations in the Nav1.2 α-subunit causative for a PRRT2-like phenotype with neonatal-infantile seizures show similar increases in Na+ current (Heron et al., 2002; Scalmani et al., 2006; Liao et al., 2010). Finally, low doses of Na+ channel blockers, such as carbamazepine, are highly effective in ameliorating most of the paroxysmal manifestations associated with PRRT2 mutations (Chen et al., 2011; Dale et al., 2014; Mao et al., 2014).

Individuals carrying the same PRRT2 mutation may show variable phenotypes, manifesting different symptoms (Brueckner et al., 2014) or presenting multiple disorders (Ebrahimi-Fakhari et al., 2015; Gardiner et al., 2015). A similar pleiotropy is observed in other channelopathies (Dichgans et al., 2005; Rajakulendran et al., 2012). It is possible that the differential temporal and regional expression of Na+ channel subtypes, as well as the impact of PRRT2 at the synaptic level, strongly contribute to modulate the phenotypic expression of PRRT2 mutations.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that the lack of PRRT2 leads to a hyperactivity of voltage-dependent Na+ channels in homozygous PRRT2-KO human and mouse neurons and that, in addition to the reported synaptic functions, PRRT2 is an important negative modulator of Nav1.2 and Nav1.6 channels. Accordingly, the well-known efficacy of ion channel blockers may not consist in a nonspecific suppression of neuronal hyperexcitability, but rather in the blockade of a specific molecular mechanism uncovered by this study. In conclusion, PRRT2 is a gene with pleiotropic functions in the control of neuronal excitability and synaptic transmission. Given the predominant paroxysmal character of PRRT2-linked diseases, the disturbance in cellular excitability by lack of negative modulation of Na+ channels appears as the key pathogenetic mechanism.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the IMPC European Consortium at the Sanger Institute (UK) in the frame of the European EMMA/Infrafrontier for making available the PRRT2 knockout mouse, drs. Enzo Wanke and Marzia Lecchi (Dept. Biotechnology and Biosciences, University of Milano Bicocca, Milano, Italy) for kindly providing the stable HEK-293 clones expressing Nav channel subtypes, Dr Luigi Naldini (Tiget, S. Raffaele Hospital, Milano, Italy) for kindly providing the lentiviral vectors and Dr Paolo Scudieri and Monica Traverso (G. Gaslini Institute, Genova, Italy) for help in the fluorescence imaging and SNP genotype assessment and Dr Sara Parodi (Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia, Genova, Italy) for help in the characterization of iPSC-neurons. We thank Drs Caterina Michetti, Monica Morini (Italian Institute of Technology, Genova, Italy) and Michele Cilli (IRCCS San Martino, Genova, Italy) for help in breeding the mice, Silvia Casagrande (Dept. Experimental Medicine, University of Genova, Italy), Arta Mehilli and Diego Moruzzo (Center for Synaptic Neuroscience, Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia, Genova, Italy) for assistance in genotyping assays and in the preparation of primary cultures.

Funding

This study was supported by research grants from Compagnia di San Paolo (to F.B.), EU FP7 Project ‘Desire’ (Grant agreement n. 602531 to F.B. and F.Z.) and ITN ‘ECMED’ (Grant agreement n. 642881 to F.B.). The support of Telethon-Italy (Grant GGP13033 to F.B. and F.Z.), CARIPLO Foundation (Grant 2013-0879 to F.B.) and Italian Ministry of Health Ricerca Finalizzata (RF-2011-02348476 to F.B. and F.Z.) is also acknowledged.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Brain online.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AIS

axon initial segment

- DIV

days in vitro

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- iPSC

induced pluripotent stem cell

- KO

knockout

- MEA

multielectrode array

- NPC

neural precursor cell

- PSTH

peristimulus time histogram

References

- Becker EB, Oliver PL, Glitsch MD, Banks GT, Achilli F, Hardy A, et al. A point mutation in TRPC3 causes abnormal Purkinje cell development and cerebellar ataxia in moonwalker mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009; 106: 6706–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brueckner F, Kohl B, Puest B, Gassner S, Osseforth J, Lindenau M, et al. Unusual variability of PRRT2 linked phenotypes within a family. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2014; 18: 540–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA. Sodium channels, inherited epilepsy, and antiepileptic drugs. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2014; 54: 317–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WJ, Lin Y, Xiong ZQ, Wei W, Ni W, Tan GH, et al. Exome sequencing identifies truncating mutations in PRRT2 that cause paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia. Nat Genet 2011; 43: 1252–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiappalone M, Bove M, Vato A, Tedesco M, Martinoia S. Dissociated cortical networks show spontaneously correlated activity patterns during in vitro development. Brain Res 2006; 1093: 41–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiappalone M, Casagrande S, Tedesco M, Valtorta F, Baldelli P, Martinoia S, et al. Opposite changes in glutamatergic and GABAergic transmission underlie the diffuse hyperexcitability of synapsin I-deficient cortical networks. Cereb Cortex 2009; 19: 1422–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman J, Jouannot O, Ramakrishnan SK, Zanetti MN, Wang J, Salpietro V, et al. PRRT2 Regulates synaptic fusion by directly modulating SNARE complex assembly. Cell Rep 2018; 22: 820–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale RC, Gardiner A, Branson JA, Houlden H. Benefit of carbamazepine in a patient with hemiplegic migraine associated with PRRT2 mutation. Dev Med Child Neurol 2014; 56: 910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debanne D, Campanac E, Bialowas A, Carlier E, Alcaraz G. Axon physiology. Physiol Rev 2011; 91: 555–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delcourt M, Riant F, Mancini J, Milh M, Navarro V, Roze E, et al. Severe phenotypic spectrum of biallelic mutations in PRRT2 gene. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2015; 86: 782–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dichgans M, Freilinger T, Eckstein G, Babini E, Lorenz-Depiereux B, Biskup S, et al. Mutation in the neuronal voltage-gated sodium channel SCN1A in familial hemiplegic migraine. Lancet 2005; 366: 371–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahimi-Fakhari D, Saffari A, Westenberger A, Klein C. The evolving spectrum of PRRT2-associated paroxysmal diseases. Brain 2015; 138: 3476–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardella E, Becker F, Møller RS, Schubert J, Lemke JR, Larsen LH, et al. Benign infantile seizures and paroxysmal dyskinesia caused by and SCN8A mutation. Ann Neurol 2016; 79: 428–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner AR, Jaffer F, Dale RC, Labrum R, Erro R, Meyer E, et al. The clinical and genetic heterogeneity of paroxysmal dyskinesias. Brain 2015; 138: 3567–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido JJ, Giraud P, Carlier E, Fernandes F, Moussif A, Fache MP, et al. A targeting motif involved in sodium channel clustering at the axonal initial segment. Science 2003; 300: 2091–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubb MS, Burrone J. Activity-dependent relocation of the axon initial segment fine-tunes neuronal excitability. Nature 2010; 465: 1070–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubb MS, Shu Y, Kuba H, Rasband MN, Wimmer VC, Bender KJ. Short- and long-term plasticity at the axon initial segment. J Neurosci 2011; 31: 16049–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron SE, Crossland KM, Andermann E, Phillips HA, Hall AJ, Bleasel A, et al. Sodium-channel defects in benign familial neonatal-infantile seizures. Lancet 2002; 360: 851–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron SE, Dibbens LM. Role of PRRT2 in common paroxysmal neurological disorders: a gene with remarkable pleiotropy. J Med Genet 2013; 50: 133–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kispersky TJ, Caplan JS, Marder E. Increase in sodium conductance decreases firing rate and gain in model neurons. J Neurosci 2012; 32: 10995–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kole MH, Ilschner SU, Kampa BM, Williams SR, Ruben PC, Stuart GJ. Action potential generation requires a high sodium channel density in the axon initial segment. Nat Neurosci 2008; 11: 178–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kole MH, Stuart GJ. Is action potential threshold lowest in the axon? Nat Neurosci 2008; 11: 1253–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuba H, Oichi Y, Ohmori H. Presynaptic activity regulates Na+ channel distribution at the axon initial segment. Nature 2010; 465: 1075–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labate A, Tarantino P, Viri M, Mumoli L, Gagliardi M, Romeo A, et al. Homozygous c.649dupC mutation in PRRT2 worsens the BFIS/PKD phenotype with mental retardation, episodic ataxia, and absences. Epilepsia 2012; 53: e196–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HY, Huang Y, Bruneau N, Roll P, Roberson ED, Hermann M, et al. Mutations in the gene PRRT2 cause paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia with infantile convulsions. Cell Rep 2012; 1: 2–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Ma Y, Zhang K, Gu J, Tang F, Chen S, et al. Aberrant transcriptional networks in step-wise neurogenesis of paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia-induced pluripotent stem cells. Oncotarget 2016; 7: 53611–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Niu F, Zhu X, Wu X, Shen N, Peng X, et al. PRRT2 mutant leads to dysfunction of glutamate signaling. Int J Mol Sci 2015; 16: 9134–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y, Deprez L, Maljevic S, Pitsch J, Claes L, Hristova D, et al. Molecular correlates of age-dependent seizures in an inherited neonatal-infantile epilepsy. Brain 2010; 133: 1403–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YT, Nian FS, Chou WJ, Tai CY, Kwan SY, Chen C, et al. PRRT2 mutations lead to neuronal dysfunction and neurodevelopmental defects. Oncotarget 2016; 7: 39184–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magistretti J, Castelli L, Forti L, D'Angelo E. Kinetic and functional analysis of transient, persistent and resurgent sodium currents in rat cerebellar granule cells in situ: an electrophysiological and modelling study. J Physiol 2006; 573: 83–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao CY, Shi CH, Song B, Wu J, Ji Y, Qin J, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlation in a cohort of paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia cases. J Neurol Sci 2014; 340: 91–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita K, Wakamori M, Rhyu IJ, Arii T, Oda S, Mori Y, et al. Bidirectional alterations in cerebellar synaptic transmission of tottering and rolling Ca2+ channel mutant mice. J Neurosci 2002; 22: 4388–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michetti C, Castroflorio E, Marchionni I, Forte N, Sterlini B, Binda F, et al. The PRRT2 knockout mouse recapitulates the neurological diseases associated with PRRT2 mutations. Neurobiol Dis 2017a; 99: 66–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michetti C, Corradi A, Benfenati F. PRRT2, a network stability gene. Oncotarget 2017b; 8: 55770–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien JE, Sharkey LM, Vallianatos CN, Han C, Blossom JC, Yu T, et al. Interaction of voltage-gated sodium channel Nav1.6 (SCN8A) with microtubule-associated protein Map1b. J Biol Chem 2012; 287: 18459–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogiwara I, Miyamoto H, Morita N, Atapour N, Mazaki E, Inoue I, et al. Nav1.1 localizes to axons of parvalbumin-positive inhibitory interneurons: a circuit basis for epileptic seizures in mice carrying an Scn1a gene mutation. J Neurosci 2007; 27: 5903–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Z, Kao T, Horvath Z, Lemos J, Sul JY, Cranstoun SD, et al. A common ankyrin-G-based mechanism retains KCNQ and NaV channels at electrically active domains of the axon. J Neurosci 2006; 26: 2599–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajakulendran S, Kaski D, Hanna MG. Neuronal P/Q-type calcium channel dysfunction in inherited disorders of the CNS. Nat Rev Neurol 2012; 8: 86–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scalmani P, Rusconi R, Armatura E, Zara F, Avanzini G, Franceschetti S, et al. Effects in neocortical neurons of mutations of the NaV1.2 Na+ channel causing benign familial neonatal-infantile seizures. J Neurosci 2006; 26: 10100–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Kirwan P, Livesey FJ. Directed differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells to cerebral cortex neurons and neural networks. Nat Protoc 2012; 7: 1836–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skarnes WC, Rosen B, West AP, Koutsourakis M, Bushell W, Iyer V, et al. A conditional knockout resource for the genome-wide study of mouse gene function. Nature 2011; 474: 337–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan GH, Liu YY, Wang L, Li K, Zhang ZQ, Li HF, et al. PRRT2 deficiency induces paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia by regulating synaptic transmission in cerebellum. Cell Res 2018; 28: 90–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasoni R, Repetto D, Morini R, Elia C, Gardoni F, Di Luca M, et al. SNAP-25 regulates spine formation through postsynaptic binding to p140Cap. Nat Commun 2013; 4: 2136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vacher H, Mohapatra DP, Trimmer JS. Localization and targeting of voltage-dependent ion channels in mammalian central neurons. Physiol Rev 2008; 88: 1407–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente P, Castroflorio E, Rossi P, Fadda M, Sterlini B, Cervigni RI, et al. PRRT2 is a key component of the Ca2+-dependent neurotransmitter release machinery. Cell Rep 2016a; 15: 117–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente P, Lignani G, Medrihan L, Bosco F, Contestabile A, Lippiello P, et al. Cell adhesion molecule L1 contributes to neuronal excitability regulating the function of voltage-gated Na+ channels. J Cell Sci 2016b; 129: 1878–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valtorta F, Benfenati F, Zara F, Meldolesi J. PRRT2: from paroxysmal disorders to regulation of synaptic function. Trends Neurosci 2016; 39: 668–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Pelt J, Corner MA, Wolters PS, Rutten WLC, Ramakers GJA. Long-term stability and developmental changes in spontaneous network burst firing patterns in dissociated rat cerebral cortex cell cultures on multi-electrode arrays. Neurosci Lett 2004; 361: 86–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Z, Nguyen HN, Guo Z, Lalli MA, Wang X, Su Y, et al. Synaptic dysregulation in a human iPS cell model of mental disorders. Nature 2014; 515: 414–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Bacaj T, Morishita W, Goswami D, Arendt KL, Xu W, et al. Postsynaptic synaptotagmins mediate AMPA receptor exocytosis during LTP. Nature 2017; 544: 316–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang SZ, Li HF, Ma LX, Qian WJ, Wang ZF, Wu ZY. Urine-derived induced pluripotent stem cells as a modeling tool for paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia. Biol Open 2015; 4: 1744–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.