Abstract

Smith et al. (Env. Health Perspect. 124: 713, 2016) identified 10 key characteristics (KCs), one or more of which are commonly exhibited by established human carcinogens. The KCs reflect the properties of a cancer-causing agent, such as ‘is genotoxic,’ ‘is immunosuppressive’ or ‘modulates receptor-mediated effects,’ and are distinct from the hallmarks of cancer, which are the properties of tumors. To assess feasibility and limitations of applying the KCs to diverse agents, methods and results of mechanistic data evaluations were compiled from eight recent IARC Monograph meetings. A systematic search, screening and evaluation procedure identified a broad literature encompassing multiple KCs for most (12/16) IARC Group 1 or 2A carcinogens identified in these meetings. Five carcinogens are genotoxic and induce oxidative stress, of which pentachlorophenol, hydrazine and malathion also showed additional KCs. Four others, including welding fumes, are immunosuppressive. The overall evaluation was upgraded to Group 2A based on mechanistic data for only two agents, tetrabromobisphenol A and tetrachloroazobenzene. Both carcinogens modulate receptor-mediated effects in combination with other KCs. Fewer studies were identified for Group 2B or 3 agents, with the vast majority (17/18) showing only one or no KCs. Thus, an objective approach to identify and evaluate mechanistic studies pertinent to cancer revealed strong evidence for multiple KCs for most Group 1 or 2A carcinogens but also identified opportunities for improvement. Further development and mapping of toxicological and biomarker endpoints and pathways relevant to the KCs can advance the systematic search and evaluation of mechanistic data in carcinogen hazard identification.

The use of the KCs of carcinogens provides an objective approach to identify and evaluate mechanistic studies pertinent to cancer induction. Analysis of data from eight recent IARC Monograph meetings revealed strong evidence for multiple KCs for most Group 1 or 2A known and probable human carcinogens.

Introduction

The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) Monographs Programme identifies the causes of human cancer. IARC assembles expert Working Groups, free of conflicts of interest, to evaluate agents that have evidence of human exposure and are suspected to be carcinogens. The cancer hazard classification methodology, outlined in the IARC Preamble (1), is based on the systematic assembly, review and integration of evidence of cancer in humans, cancer in experimental animals and cancer mechanisms. To date, more than 1000 agents have been classified. IARC evaluations are used worldwide by national and international health agencies to support a wide range of subsequent activities ranging from research, to risk assessment, to preventative actions (2).

Of the around 120 agents classified in Group 1 (carcinogenic to humans; see Table 1) by IARC, most have ‘sufficient’ evidence for their carcinogenicity in humans based on epidemiological studies. However, epidemiological studies of cancer in exposed humans are often limited in number and may have deficiencies in terms of sample size, confounding and exposure characterization. Furthermore, for chemicals that have been introduced recently on the market, epidemiological studies may not exist or be relevant because of the long latency period for cancer development. Lifetime rodent cancer bioassays are declining in number, with only a fraction of the ~75 000 in the Toxic Substances Control Act Chemical Substance Inventory having been formally evaluated by the National Toxicology Program (NTP) (3,4). In contrast, data on cancer mechanisms from human biomarker studies, in vivo animal tests and in vitro cell culture models are increasing in both volume and diversity (5–8). This includes human in vitro test systems to detect effects on a variety of biological receptors and to explore genetic susceptibility (6,9).

Table 1.

Definitions of the IARC classifications

| Classification | Definition |

|---|---|

| Group 1 | Carcinogenic to humans |

| Group 2A | Probably carcinogenic to humans |

| Group 2B | Possibly carcinogenic to humans |

| Group 3 | Not classifiable as to its carcinogenicity to humans |

| Group 4 | Probably not carcinogenic to humans |

When the evidence from human epidemiologic studies is less than sufficient, strong mechanistic data can play a pivotal role in the overall carcinogen hazard classification (10,11). For instance, even though the evidence from rodent cancer bioassays provided ‘sufficient’ evidence of cancer in animals, d-limonene was classified in Group 3 (not classifiable as to its carcinogenicity to humans) on the basis of mechanistic and other relevant data because the probable mechanism of carcinogenicity in animals was unlikely to be operative in humans (12). Other agents have been classified in Group 2A (probably carcinogenic to humans) or even in Group 1 (carcinogenic in humans) based on strong evidence for recognized carcinogen mechanisms, e.g. genotoxicity (ethylene oxide (13)), inhibiting DNA repair (etoposide (14)) or binding to the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) and subsequent downstream effects (2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzodioxin [TCDD] (10,15)).

A recent review of these agents and all other Group 1 human carcinogens classified in Volumes 1–99 identified several issues relevant to improving the evaluation of mechanistic data for carcinogen hazard identification (16). First, it was noted that many human carcinogens showed a number of characteristics that are shared among carcinogenic agents. Second, different human carcinogens may exhibit a different spectrum of these key characteristics (KCs) and operate through distinct mechanisms. Third, for many carcinogens evaluated prior to Volume 100, few data were available on some mechanisms of recognized importance in carcinogenesis, such as epigenetic alterations (17). Fourth, the evaluation of mechanistic and other relevant data has been further challenged by the lack of a systematic and transparent method to search for and assemble mechanistic data for cancer hazard identification. Specifically, there was no widely accepted method to search systematically for relevant mechanisms, resulting in a lack of uniformity in the mechanistic topics addressed across assessments. Finally, there was no procedure to efficiently organize, analyze and interpret the voluminous mechanistic studies.

To address these challenges, the KCs of human carcinogens were recently introduced as the basis of a uniform approach for searching, organizing and evaluating mechanistic evidence to support cancer hazard identification (16). The KCs comprise the properties of known human carcinogens. These characteristics are distinct from the hallmarks of cancer that relate to the properties of cancer cells (18,19) but instead reflect the ability of a carcinogen to, for example, be genotoxic, be immunosuppressive or modulate receptor-mediated effects (see Table 2). Established human carcinogens commonly exhibit one or more of these characteristics, and, therefore, data on these characteristics can provide independent evidence of carcinogenicity when human data are lacking. Such data can also help in interpreting the relevance and importance of findings of cancer in animals and in humans.

Table 2.

The KCs of human carcinogens (from (16))

| Key characteristic | Example relevant evidence |

|---|---|

| 1. Is electrophilic or can be metabolically activated | Parent compound or metabolite with an electrophilic structure (e.g. epoxide, quinone, etc.), formation of DNA and protein adducts. |

| 2. Is genotoxic | DNA damage (DNA strand breaks, DNA-protein cross-links, unscheduled DNA synthesis), intercalation, gene mutations, cytogenetic changes (e.g. chromosome aberrations, micronuclei). |

| 3. Alters DNA repair or causes genomic instability | Alterations of DNA replication or repair (e.g. topoisomerase II, base-excision or double-strand break repair) |

| 4. Induces epigenetic alterations | DNA methylation, histone modification, microRNAs |

| 5. Induces oxidative stress | Oxygen radicals, oxidative stress, oxidative damage to macromolecules (e.g. DNA, lipids) |

| 6. Induces chronic inflammation | Elevated white blood cells, myeloperoxidase activity, altered cytokine and/or chemokine production |

| 7. Is immunosuppressive | Decreased immunosurveillance, immune system dysfunction |

| 8. Modulates receptor-mediated effects | Receptor in/activation (e.g. ER, PPAR, AhR) or modulation of endogenous ligands (including hormones) |

| 9. Causes immortalization | Inhibition of senescence, cell transformation |

| 10. Alters cell proliferation, cell death or nutrient supply | Increased proliferation, decreased apoptosis, changes in growth factors, energetics and signaling pathways related to cellular replication or cell-cycle control, angiogenesis |

ER, estrogen receptor; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor.

Herein, we describe and discuss the application of these KCs in IARC Monograph evaluations that have taken advantage of the systematic consideration of mechanistic evidence. The strengths and weaknesses of this approach are discussed, as are opportunities for further progress and refinement. We further discuss how the paradigm could be expanded to other endpoints and how future toxicological and molecular epidemiological studies could be developed to generate more useful information for the process of carcinogen evaluation.

Methods

Methods and results of mechanistic evaluations were compiled from the more than 30 agents evaluated in Meetings 112–119 of the IARC Monographs (20), based on the Lancet Oncology publications (21–28) and published Monographs (29). As noted in the Preamble to the IARC Monographs (1) and Instructions to Authors ((30); see also (31)), the mechanistic data search, organization and evaluation procedures were as follows:

A working list of endpoints associated with each KC was developed by IARC in collaboration with the expert Working Groups (Supplementary Table 1, available at Carcinogenesis Online).

For the Monograph Meetings 112–119 (20,29), IARC Monographs staff performed initial literature searches for studies on the agent using a working list of search terms for the KCs developed by IARC in collaboration with the expert Working Groups (see Supplementary Table 2, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Additional complementary literature searches by IARC and the Working Groups incorporated terms for the agent and metabolites, alone or in combination with terms related to carcinogenicity. Literature identified through other searches (e.g. from reference lists of retrieved articles, past Monographs or other authoritative reviews) was also included.

- The literature review, study exclusion and categorization of included studies were performed by the Volume 112 expert Working Group members and by IARC Monographs staff for subsequent meetings, with further review and refinement by each expert Working Group. Specifically, the steps involved entailed:

- ○ Based on title and abstract review, studies were excluded if they were not about the agent (or a metabolite) or if they reported no data on mechanistic or toxicological endpoints.

- ○ Included studies were further sorted into categories representing the 10 KCs (see Table 2), based on the mechanistic endpoints and species evaluated. When the included literature on the KCs of carcinogens was especially voluminous, further categorization was by species (human, mammalian, nonmammalian) and study type (e.g. in vitro, in vivo).

- ○ Reviews, gene expression studies and articles relevant to toxicokinetics, toxicity or susceptibility were also identified.

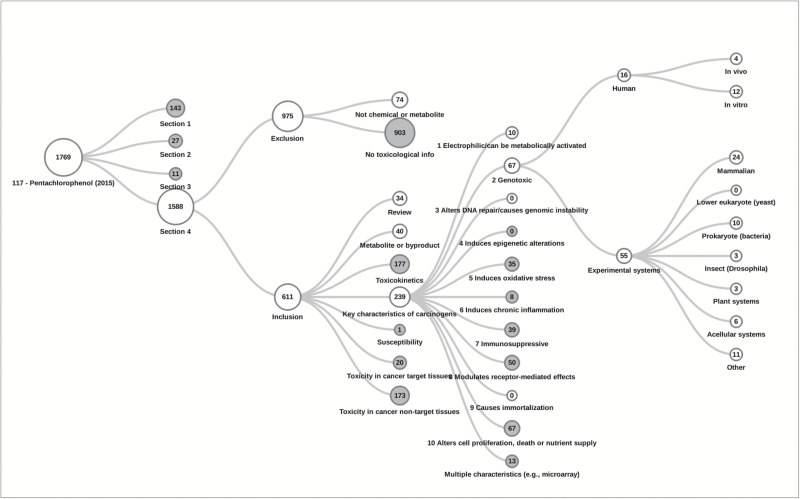

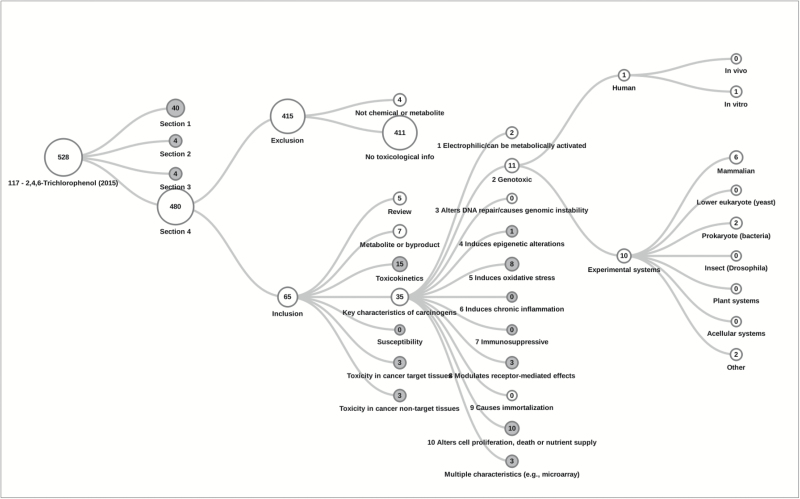

- ○ For these evaluations, the Health Assessment Workplace Collaborative (https://HAWCproject.org) was used to record the literature search terms, sources, articles retrieved, exclusion criteria and categorization of included articles. Examples of the resulting literature flow diagrams are shown in Figures 1 and 2.

In addition, the Volume 112 Working Group, together with IARC Monographs staff, mapped the Tox21/ToxCast high-throughput assays to the 10 KCs to facilitate systematic evaluation as an additional mechanistic data stream (31). Subsequent Working Groups refined this approach, mapping additional assays when they became available for the KCs and performing analyses as described by Chiu et al. (11).

Figure 1.

Results of the search, screening and organization of the published scientific literature, according to the KCs and other topics relevant to mechanistic data evaluation for PCP (Group 1, IARC Monograph Meeting 117). Of note, more than one exclusion criteria may apply to each excluded study, and more than one category may apply to included studies (e.g. if more than one KC, endpoint, species, etc. was evaluated).

Figure 2.

Results of the search, screening and organization of the published scientific literature, according to the KCs and other topics relevant to mechanistic data evaluation for 2,4,6-trichlorophenol (Group 2B, IARC Monograph Meeting 117). Of note, more than one exclusion criteria may apply to each excluded study, and more than one category may apply to included studies (e.g. if more than one KC, endpoint, species, etc. was evaluated).

Each IARC Working Group considered the extent to which relevant mechanistic events had been established, including whether the mechanistic event has been challenged experimentally, as well as the consistency of the results in different experimental systems and the overall coherence of the database (1). As a result, the evidence was classified based on collective expert judgment as ‘strong, moderate or weak’ based on the assembled mechanistic information. As outlined in the Instructions to Authors (30), these classifications were based on the extent of data available that met the criteria in the IARC Monographs Preamble (1), addressed the range of study designs and doses/concentrations tested, and included consideration of whether or not the effects were observed at the physiological, cellular or molecular level, as well as the presence of any consistencies or differences in results within and across experimental designs. Emphasis was given to existing mechanistic data from human-related studies, and gaps in evidence were identified. In general, in experimental systems, studies of repeated doses and of chronic exposures were accorded greater importance than studies of a single dose or time point. Consideration was also given to the extent of concurrent toxicity that was observed. Route of exposure was considered a less important factor in the evaluation of experimental studies, in recognition that the exposures and target tissues may vary across experimental models and in exposed human populations. Another important aspect of the evaluation was the assessment of whether the mechanism can operate in humans (1). Accordingly, human biomarker studies incorporating endpoints relevant to the KCs of carcinogens were deemed to be especially valuable when available.

Results

Evaluations in which the KCs were applied

The KCs have been applied in eight IARC Monograph Working Group meetings to date (20,29), in which 34 agents were classified as to their cancer hazard potential (Table 3). Twenty of these agents had been specifically identified as high or medium priority for a new or updated evaluation by an Advisory Group to the IARC Monographs (32). Other priority agents evaluated included those for which new cancer bioassays became available since any prior evaluation. Additionally, 12 pesticides were selected through a cheminformatics analyses from among the many pesticides and pesticide classes recommended for evaluation (33).

Table 3.

Summary of mechanistic evaluations in IARC Monograph Meetings 112–119

| Agent | Group | Cancer in humans | Cancer in animals | Number of Studies (All KCs) | KC 1 | KC 2 | KC 3 | KC 4 | KC 5 | KC 6 | KC 7 | KC 8 | KC 9 | KC 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCP | 1 | Sufficient | Sufficient | 239 | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Lindane | 1 | Sufficient | Sufficient | 375 | X | X | ||||||||

| Welding fumes | 1 | Sufficient | Sufficient | 189 | X | X | ||||||||

| Consumption of processed meat | 1 | Sufficient | Inadequate | 144a | ||||||||||

| Malathion | 2A | Limited | Sufficient | 249 | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Hydrazine | 2A | Limited | Sufficient | 117 | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| DDT | 2A | Limited | Sufficient | 745 | X | X | X | |||||||

| N,N-DMF | 2A | Limited | Sufficient | 170 | X | X | X | |||||||

| TCAB | 2A | Inadequate | Sufficient | 22 | X | X | X | |||||||

| Tetrabromobisphenol A | 2A | Inadequate | Sufficient | 147 | X | X | X | |||||||

| Diazinon | 2A | Limited | Limited | 125 | X | X | ||||||||

| Glyphosate | 2A | Limited | Sufficient | 146 | X | X | ||||||||

| 2-Mercaptobenzothiazole | 2A | Limited | Sufficient | 19 | ||||||||||

| Consumption of red meat | 2A | Limited | Inadequate | 144a | ||||||||||

| Dieldrin and aldrin metabolized to dieldrin | 2A | Limited | Sufficient | 237 | ||||||||||

| Very hot beverages | 2A | Limited | Sufficient | 30b | ||||||||||

| 1-Bromopropane | 2B | Inadequate | Sufficient | 29 | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) | 2B | Inadequate | Limited | 269 | X | |||||||||

| 3-Chloro-2-methylpropene (technical grade) | 2B | Inadequate | Sufficient | 11 | X | |||||||||

| Furfuryl alcohol | 2B | Inadequate | Sufficient | 21 | X | |||||||||

| Indium tin oxide | 2B | Inadequate | Sufficient | 22 | X | |||||||||

| Melamine | 2B | Inadequate | Sufficient | 78 | X | |||||||||

| 1-tert-Butoxypropanol | 2B | Inadequate | Sufficient | 2 | ||||||||||

| 2,4,6-Trichlorophenol | 2B | Inadequate | Sufficient | 35 | ||||||||||

| β-Myrcene | 2B | Inadequate | Sufficient | 34 | ||||||||||

| Molybdenum trioxide | 2B | Inadequate | Sufficient | 9 | ||||||||||

| N,N-Dimethyl-p-toluidine | 2B | Inadequate | Sufficient | 19 | ||||||||||

| Parathion | 2B | Inadequate | Sufficient | 209 | ||||||||||

| Pyridine | 2B | Inadequate | Sufficient | 45 | ||||||||||

| Tetrachlorvinphos | 2B | Inadequate | Sufficient | 29 | ||||||||||

| Tetrahydrofuran | 2B | Inadequate | Sufficient | 22 | ||||||||||

| Vinylidene chloride | 2B | Inadequate | Sufficient | 76 | ||||||||||

| Coffee drinking | 3 | Inadequate | Inadequate | 304 | c | |||||||||

| Mate (not very hot) | 3 | Inadequate | Inadequate | 30b |

X represents strong evidence; Bold indicates agent upgraded from Group 2B to Group 2A.

aNumber of studies applies to red and processed meat; for red meat, there was strong mechanistic evidence for meat components.

bApplies to mate and hot beverages.

cAntioxidant effects.

As illustrated in Table 3, the IARC Monograph Meeting 112–119 evaluations identified important new Group 1, Group 2A and Group 2B carcinogens and resulted in reclassifications of several agents based on new evidence (e.g. coffee (25)). The agents evaluated covered a range of diverse exposures of relevance to carcinogenicity, including occupational exposures (pesticides, welding, industrial chemicals) and consumption of meat and very hot beverages (20,29). Of note, this particular set of agents may not be representative of all carcinogens, as a much broader set of complex mixtures, occupational exposures, physical agents, biological agents and lifestyle factors have been classified in Group 1, as recently reviewed in Volume 100 of the IARC Monographs (29).

Literature search results

The extent of available evidence on cancer mechanisms was variable across the range of agents evaluated (Table 3). Agents classified in Group 1 had generally been the subject of more extensive mechanistic studies than agents classified in Groups 2 or 3. For example, as illustrated in Figures 1 and 2, 239 articles on KCs were identified for pentachlorophenol (PCP), compared with 35 for 2,4,6-trichlorophenol, despite the similar use scenarios of these two agents. For most agents evaluated as Group 2B or 3, data on KCs were sparse. For instance, for more than half of the 16 agents evaluated in Group 2B, fewer than 30 articles were included on all KCs following targeted literature searches (e.g. for 1-bromopropane, 3-chloro-2-methylpropene, furfuryl alcohol, indium tin oxide, 1-tert-butoxypropanol, molybdenum trioxide, N,N-dimethyl-p-toluidine, tetrachlorvinphos and tetrahydrofuran). A notable exception was 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D), for which more than 200 studies on KCs were identified. However, nearly half of these publications concerned the genotoxicity of 2,4-D, a KC for which there was not strong evidence. Of agents evaluated in Group 2B or 3, coffee was among the most widely studied, with over 300 publications covering a broad range of KCs. As part of the large database of human observational and experimental studies, these mechanistic studies were supportive but not influential in the overall evaluation (which was based on ‘inadequate’ evidence in humans) (25). For all Group 1 and most Group 2A agents [with the exception of 2-mercaptobenzothiazole, tetrachloroazobenzene (TCAB) and very hot beverages], a substantial evidence database on the mechanisms of carcinogenicity was identified, encompassing hundreds of scientific publications and generally covering a range of different KCs, endpoints and test systems utilizing various exposure routes and durations.

KCs of carcinogens with strong evidence

Several of the Group 1 and Group 2A agents showed strong evidence for common sets of KCs (Table 3). PCP and hydrazine are metabolically activated to electrophilic moieties, are genotoxic, induce oxidative stress and altered cell proliferation or death (PCP) or nutrient supply (hydrazine) (24,26). PCP additionally modulates receptor-mediated effects. N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) shared some of these KCs (is metabolically activated, induces oxidative stress and alters cell proliferation) but was not considered to have strong evidence for being genotoxic (24). However, strong evidence for two of these KCs (is genotoxic, induces oxidative stress) was found for malathion, diazinon and glyphosate, with malathion additionally showing three others (induces chronic inflammation, modulates receptor-mediated effects and alters cell proliferation) (21,31).

Other Group 1 and Group 2A agents showed strong evidence for distinct sets of KCs. For instance, welding fumes induce chronic inflammation and are immunosuppressive (27). The strong evidence encompassed numerous panel studies of cross-sectional and cohort design demonstrating increases in lung and systemic inflammation biomarkers. Risk for infection in exposed workers was increased in epidemiological studies of different design. The consistent and coherent evidence from human studies of welders was further supported by findings in experimental systems showing that welding fumes impaired resolution of pulmonary infection and induced chronic pulmonary inflammation. Similar to welding fumes, chronic studies in rodents provided strong evidence for other agents that induce chronic inflammation (e.g. malathion, TCAB, indium tin oxide and melamine (21,26–28,31). On the other hand, there was strong evidence for a different set of KCs (modulates receptor-mediated effects, is immunosuppressive and induces oxidative stress) for dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) and tetrabromobisphenol A (22,24).

For the agents evaluated in Group 2B or Group 3, there was usually strong evidence for at most one KC (see Table 3). An exception was 1-bromopropane, which had strong evidence of multiple KCs, primarily from experimental systems (24). This strong evidence from experimental systems did not warrant a change in the overall classification of 1-bromopropane, however, as the IARC Monographs Preamble requires ‘strong evidence from exposed humans’ (for Group 1) or that the mechanism has been shown to ‘also operate in humans’ (for Group 2A) (1). The agents with strong evidence for one KC included furfuryl alcohol, which is metabolically activated to the electrophilic 2-sulphoxymethylfuran, while 2,4-D induces oxidative stress and indium tin oxide induces chronic inflammation (22,27,28). Coffee drinking was associated with antioxidant effects (25). Only one agent (3-chloro-2-methylpropene) was determined to be genotoxic (24), although data for this KC were broadly available for many compounds under consideration, usually from the standard battery of genotoxicity assays performed in conjunction with chronic bioassays and from published reports. Similarly, some agents (e.g. melamine, β-myrcene) were specifically noted as not being genotoxic (28); a lack of genotoxicity is one of the seven criteria that must all be met in order to conclude that rodent carcinogens operate through a mechanism not relevant to humans (i.e. due to precipitates in the bladder or α2u-globulin in the kidney) (34). Regarding the latter, four of the agents evaluated (1-tert-butoxypropanol, β-myrcene, pyridine and tetrahydrofuran) increased kidney α2u-globulin in male rats, but none satisfied the seven IARC criteria for an α2u-globulin-associated tumorigenic response (28,34).

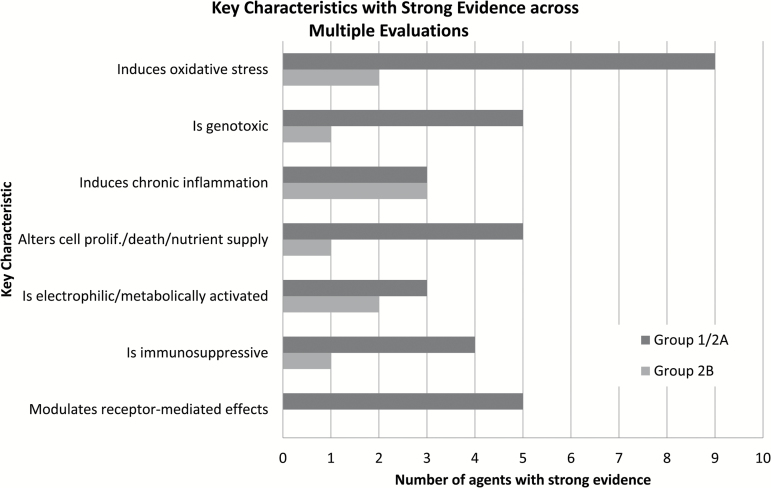

The KC most often showing ‘strong’ evidence across all 34 agents evaluated in IARC Monograph Meetings 112–119 was ‘induces oxidative stress’ (11 agents; see Figure 3). For agents that induce oxidative stress (e.g. PCP, 2,4-D (22,26)), experimental studies of the effect of antioxidants or in knockout animals were part of the strong dataset. For all but one agent (2,4-D), this KC was accompanied by strong evidence for one or more other KCs (see Table 3). This is perhaps not surprising, given the close association of the underlying cancer mechanisms, with strong evidence that they induce oxidative stress adding support to findings for these other KCs (e.g. oxidatively damaged DNA). However, oxidative stress is not unique to cancer, and strong evidence that 2,4-D induces oxidative stress did not result in a change in the overall cancer hazard classification. Other KCs seen with multiple agents were ‘is genotoxic’ (six agents), ‘induces chronic inflammation’ (six agents), ‘alters cell proliferation, cell death or nutrient supply’ (six agents), ‘is electrophilic or can be metabolically activated’ (five agents), ‘is immunosuppressive’ (five agents) and ‘modulates receptor-mediated effects’ (five agents). No agent had strong evidence for three KCs (alters DNA repair or causes genomic instability, induces epigenetic alterations and causes immortalization).

Figure 3.

KCs of carcinogens with strong evidence across multiple evaluations. The number of Group 1/2A and Group 2B carcinogens with strong evidence for each characteristic is indicated, of 34 agents evaluated. All but one of the Group 2B carcinogens (1-bromopropane, see Table 3) had strong evidence for only one KC. No agent had strong evidence for three KCs (alters DNA repair or causes genomic instability; induces epigenetic alterations and causes immortalization).

Impact of mechanistic data on the overall evaluation of carcinogenicity by IARC Monograph Working Groups

The agents with ‘sufficient’ or ‘limited’ evidence of cancer in humans often exhibited strong evidence of multiple KCs; however, the mechanistic data did not affect the overall classification of these agents. The classification of four agents in Group 1 (e.g. PCP, lindane, welding fumes and consumption of processed meat) was based on ‘sufficient’ evidence of cancer in humans (22,23,26,27). When available, ‘limited’ evidence of cancer in humans was the basis of Group 2A evaluations, alone (diazinon and consumption of red meat) or together with ‘sufficient’ evidence of cancer in experimental animals (malathion, hydrazine, DDT, DMF, glyphosate, 2-mercaptobenzothiazole, very hot beverages, dieldrin and aldrin metabolized to dieldrin) (21–26). The mechanistic data supported a change in the overall evaluation for very few agents, only two, tetrabromobisphenol A and TCAB, of the 34 evaluations in Monograph Meetings 112–119. In both cases, the mechanistic data provided strong evidence of multiple KCs and supported an upgrade in the cancer hazard classification, from Group 2B to Group 2A (24,26).

Specifically, tetrabromobisphenol A was classified in Group 2A on the basis of sufficient evidence of carcinogenicity in animals and the strong mechanistic evidence on three KCs (modulates receptor-mediated effects, is immunosuppressive and induces oxidative stress) that were shown to ‘also operate in humans’ (1,24). On the other hand, TCAB was classified in Group 2A because it belongs, on the basis of mechanistic considerations, to the class of agents that activate AhR, and some members of this class have previously been evaluated as Group 1 or Group 2A carcinogens (1,26). In addition to the strong evidence of multiple KCs, TCAB has structural resemblance to AhR agonists classified in Group 1, causing a similar pattern of tumors in experimental animals and induces pathognomonic responses for AhR activation (e.g. chloracne in multiple species).

Discussion

Mechanistic data are an integral part of all cancer hazard evaluations and by extension of all human health risk assessment (1,3,10,35–37) but still pose a challenge to decisionmakers as there is no generally accepted procedure to efficiently organize, analyze and interpret the voluminous number of mechanistic studies. One framework that has been widely used and promoted is the mode of action (MOA) approach (38), which subdivides the pathway between an agent (exposure) and an adverse effect into a series of hypothesized key events. This pathway-based approach has been further developed into the more recent adverse outcome pathway (AOP) framework, which was initially described by the ecotoxicology community (39). However, the hypothesized key events that form the common basis of MOAs and AOPs are inherently limited by the current understanding of the disease process. This limitation was recognized by Sir Bradford Hill, who noted that ‘what is biologically plausible depends upon the biological knowledge of the day’ and described the biological plausibility of a suspected causation as ‘helpful’ but not necessary (40).

In a research setting, it is essential that scientific hypotheses can be continually modified, updated and repeatedly tested. However, in the context of hazard evaluation and risk assessment, a hypothesis-based paradigm can introduce bias because focusing on a specific set of hypothesized key events inherently results in exclusion of data, leading to analyses that favor one or more particular mechanisms or series of key events. As a related challenge, an uneven level of experimental results can result from disproportionate resources having been focused on investigating a favored mechanism (1). Moreover, as biological knowledge develops, hypothesized key events and MOA/AOP may be shown to be incorrect or incomplete (3,41).

Other efforts to establish systematic approaches for reviewing mechanistic studies have been initiated, such as by gathering information on postulated mechanisms (e.g. blood IGF1 and prostate cancer) (42,43). A separate approach sought to broaden consideration of cancer mechanisms by organizing them according to the hallmarks of cancer (44). However, as the hallmarks characterize frank tumors that are evident at the end of the carcinogenic process (18,19), they are distinct from the effects of carcinogens and may not capture fully important mechanistic effects that occur early or transiently throughout tumor development.

Here, we have described our recent experience with a novel alternative approach that does not require postulating the mechanism or MOA by which a chemical causes cancer in animals and/or humans. Rather, the approach utilizes the KCs of human carcinogens as the basis of a uniform approach to search, organize and evaluate mechanistic evidence to support cancer hazard identification (16). These KCs comprise 10 properties of known human carcinogens. The 2017 National Academy of Sciences report on ‘Using 21st Century Science to Improve Risk-Related Evaluations’ recently opined that the KCs approach ‘avoids a narrow focus on specific pathways and hypotheses and provides for a broad, holistic consideration of the mechanistic evidence.’ (45) The KCs have been used by the IARC Monographs Programme to evaluate the mechanistic data compiled for the more than 30 agents evaluated in Meetings 112–119 of the IARC Monographs (20,29). As also indicated in the 2017 National Academy of Sciences report, the KCs approach could be expanded to other endpoints, including endocrine disruption and cardiovascular disease (45). This effort could be informed by the experience described herein, and the strengths and weaknesses of the approach highlighted below.

Recent experiences with the KCs of carcinogens reveal a number of strengths, such as allowing for a systematic search and assembly of the relevant literature, followed by organization of the studies into easily reviewable groupings (see Figures 1 and 2). This review process revealed strong evidence of KCs for many agents classified in the higher categories of Group 1 or 2A (see Figure 3). Indeed, 11 of 12 agents with strong evidence for two or more KCs were classified in Group 1 or 2A. On the other hand, for five other classifications in Group 1 or 2A (dieldrin and aldrin metabolized to dieldrin, consumption of processed meat, consumption of red meat, very hot beverages and 2-mercaptobenzothiazole), there was no strong evidence for any KC. For dieldrin, a substantial literature was identified, but coverage of the KCs was incomplete, and findings lacked consistency and coherence. Many mechanistic studies were also identified for meat, but studies of the consumption of the meat itself were sparse, even though important components of red and processed meat showed strong evidence for certain KCs. For very hot beverages and 2-mercaptobenzothiazole, only a few mechanistic studies were available. Very hot beverages are difficult to study mechanistically, even though heat is obviously cytotoxic and will induce tissue damage and inflammation. Finally, for most agents (with welding as a notable exception (27)), few studies of biomarker endpoints relevant to the KCs in exposed humans were available. Such studies have been encouraged by the National Academy of Science of the USA (5), and future effort in this area will be of importance and relevance to any evaluation of evidence for KCs.

For two agents, tetrabromobisphenol A and TCAB, out of 34 total, strong evidence for distinct KCs resulted in their upgrade to Group 2A even though the epidemiological findings were considered inadequate (24,26). Oxidative stress was the most common KC identified with strong evidence across all the agents evaluated, but this was found in conjunction with other KCs in all cases except for 2,4-D. 2,4-D was classified as a Group 2B carcinogen (22), and a subsequent meta-analysis has provided new evidence for an association between lymphoma and exposure to 2,4-D (46). However, noncarcinogens can also induce oxidative stress, and so, this KC should be interpreted with caution. Overall, a structured approach based on KCs performed well in helping evaluate the carcinogenicity of the 34 agents discussed here, and the agents with the strongest evidence of carcinogenicity had more KCs with strong as a descriptor. In all cases, the use of a transparent search tool and the binning of data clearly helped the expert working group organize and evaluate the mechanistic data and is an important element to take forward in the extension of the approach to other endpoints.

Several weaknesses, however, could be addressed moving forward. The mechanistic data in general, and especially novel high-throughput data stream from very large toxicity testing programs, are not without important limitations. These have been extensively covered elsewhere (45,47–49), so only a few points will be highlighted. The major technical limitations include general deficiency in metabolic capacity in assays, limited biological coverage of the mechanistic assays for the KCs (11), extrapolation of in vitro to in vivo exposures and challenges with validation, which cannot match the pace of development of new assays, models and test systems. In addition to having little overall impact on the mechanistic evaluation of an agent, analyses of the ToxCast/Tox21 assays revealed adequate coverage for very few of the KCs (11), a critical data gap that also merits consideration as these assays are applied in evaluation of other toxicological endpoints.

Opportunities for refinement that are also relevant to other applications of the approach include (i) clearly delineating the toxicological and biomarker endpoints associated with each KC; (ii) developing sensitive and specific literature search terms for each KC and applying the latest bioinformatic tools in literature searching; (iii) promoting uniformity of evaluations through the documentation and clarification of procedures by the IARC Secretariat, including development of examples of ‘strong’ evidence for a KC based on the extent of testing in different systems (in humans, in chronic and in vivo settings in rodents and in vitro); (iv) exploring approaches to integrate evidence across KCs (e.g. when evidence of one KC would be alone sufficient to result in any change in the overall cancer hazard classification and whether evidence of specific groups of KCs would otherwise be needed) and (v) soliciting feedback after each Monograph meeting to continue to identify issues arising in the evaluation and opportunities for progress.

Overall, we show that application of the KCs to hazard identification is a robust new approach to organizing and evaluating the mechanistic data related to carcinogenesis that avoids the need to identify, and thereby restrict attention to, specific pathways and hypotheses. Because they are based on empirical observations of characteristics associated with known carcinogens, the KCs thus provide a more agnostic and unbiased survey of the mechanistic literature. This approach has been successfully applied in eight IARC Monograph meetings evaluating 34 agents, but this experience also points to a number of potential refinements that can further improve the evaluation of mechanistic data to support identification of human carcinogenic agents.

Supplementary material

Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 can be found at Carcinogenesis online.

Funding

We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the National Institutes of Health, USA (U01 CA33193, K.Z.G.; Superfund grant NIH P42ES004705, M.T.S.; Superfund grant P42ES027704, I.R. and W.A.C.) and the European Union Programme for Employment and Social Innovation “EaSI” (2014-2020) (K.Z.G.).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the IARC Working Groups, IARC secretariat and other participants for IARC Monograph Meetings 112–119. The views expressed in this manuscript do not necessarily represent those of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration or the European Commission.

Conflict of Interest Statement: None of the authors have any conflict of interest regarding the chemical agents or topics discussed.

Abbreviations

- AhR

aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- AOP

adverse outcome pathway

- KCs

key characteristics

- MOA

mode of action

- NTP

National Toxicology Program

- PCP

pentachlorophenol

- TCAB

tetrachloroazobenzene

- TCDD

2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin.

References

- 1. IARC. (2006)Preamble to the IARC Monographs http://monographs.iarc.fr/ENG/Preamble/index.php.

- 2. Pearce N., et al. (2015)IARC monographs: 40 years of evaluating carcinogenic hazards to humans. Environ. Health Perspect., 123, 507–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Guyton K.Z., et al. (2009)Improving prediction of chemical carcinogenicity by considering multiple mechanisms and applying toxicogenomic approaches. Mutat. Res., 681, 230–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. National Toxicology Program. (2017)Testing Information https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/testing/index.html.

- 5. National Academy of Science. (2007)Applications of Toxicogenomic Technologies to Predictive Toxicology and Risk Assessment. National Academies Press, Washington, DC. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fielden M.R., et al. (2018)Modernizing human cancer risk assessment of therapeutics. Trends Pharmacol. Sci., 39, 232–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tice R.R., et al. (2013)Improving the human hazard characterization of chemicals: a Tox21 update. Environ. Health Perspect., 121, 756–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Collins F.S., et al. (2008)Toxicology. Transforming environmental health protection. Science, 319, 906–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zeise L., et al. (2013)Addressing human variability in next-generation human health risk assessments of environmental chemicals. Environ. Health Perspect., 121, 23–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cogliano V.J., et al. (2008)Use of mechanistic data in IARC evaluations. Environ. Mol. Mutagen., 49, 100–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chiu W.A., et al. (2018)Use of high-throughput in vitro toxicity screening data in cancer hazard evaluations by IARC Monograph Working Groups. ALTEX, 35,51–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. (1999)Some Chemicals that Cause Tumours of the Kidney or Urinary Bladder in Rodents and Some Other Substances. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France. [Google Scholar]

- 13. IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. (1994)Some Industrial Chemicals. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France. [Google Scholar]

- 14. IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. (2012)Pharmaceuticals. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France. [Google Scholar]

- 15. IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. (1997)Polychlorinated Dibenzo-para-dioxins and Polychlorinated Dibenzofurans. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Smith M.T., et al. (2016)Key characteristics of carcinogens as a basis for organizing data on mechanisms of carcinogenesis. Environ. Health Perspect., 124, 713–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Herceg Z., et al. (2013)Towards incorporating epigenetic mechanisms into carcinogen identification and evaluation. Carcinogenesis, 34, 1955–1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hanahan D., et al. (2011)Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell, 144, 646–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hanahan D., et al. (2000)The hallmarks of cancer. Cell, 100, 57–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. IARC. Past Meetings–Recently Evaluated http://monographs.iarc.fr/ENG/Meetings/index1.php.

- 21. Guyton K.Z., et al. ; International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group, IARC, Lyon, France. (2015)Carcinogenicity of tetrachlorvinphos, parathion, malathion, diazinon, and glyphosate. Lancet. Oncol., 16, 490–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Loomis D., et al. ; International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group, IARC, Lyon, France. (2015)Carcinogenicity of lindane, DDT, and 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid. Lancet. Oncol., 16, 891–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bouvard V., et al. ; International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group. (2015)Carcinogenicity of consumption of red and processed meat. Lancet. Oncol., 16, 1599–1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Grosse Y., et al. ; International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group. (2016)Carcinogenicity of some industrial chemicals. Lancet. Oncol., 17, 419–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Loomis D., et al. ; International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group. (2016)Carcinogenicity of drinking coffee, mate, and very hot beverages. Lancet. Oncol., 17, 877–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Guyton K.Z., et al. ; International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group. (2016)Carcinogenicity of pentachlorophenol and some related compounds. Lancet. Oncol., 17, 1637–1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Guha N., et al. ; International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group. (2017)Carcinogenicity of welding, molybdenum trioxide, and indium tin oxide. Lancet. Oncol., 18, 581–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Grosse Y., et al. ; International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group. (2017)Some chemicals that cause tumours of the urinary tract in rodents. Lancet. Oncol., 18, 1003–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. IARC. (2017)Monographs and Supplements Available Online http://monographs.iarc.fr/ENG/Monographs/PDFs/index.php.

- 30. IARC. (2017)Instructions to Authors for the Preparation of Drafts for IARC Monographs http://monographs.iarc.fr/ENG/Preamble/instructions.php.

- 31. IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. (2017)Some Organophosphate Insecticides and Herbicides. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Straif K., et al. (2014)Future priorities for the IARC monographs. Lancet. Oncol., 15, 683–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Guha N., et al. (2016)Prioritizing chemicals for risk assessment using chemoinformatics: examples from the IARC monographs on pesticides. Environ. Health Perspect., 124, 1823–1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. IARC(1999)Species differences in thyroid, kidney and urinary bladder carcinogenesis. Proceedings of a Consensus Conference Lyon, France, 3–7 November 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Berggren E., et al. (2015)Chemical safety assessment using read-across: assessing the use of novel testing methods to strengthen the evidence base for decision making. Environ. Health Perspect., 123, 1232–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sturla S.J., et al. (2014)Systems toxicology: from basic research to risk assessment. Chem. Res. Toxicol., 27, 314–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Birnbaum L.S., et al. (2016)Informing 21st-century risk assessments with 21st-century science. Environ. Health Perspect., 124, A60–A63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Meek M.E., et al. (2014)New developments in the evolution and application of the WHO/IPCS framework on mode of action/species concordance analysis. J. Appl. Toxicol., 34, 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ankley G.T., et al. (2010)Adverse outcome pathways: a conceptual framework to support ecotoxicology research and risk assessment. Environ. Toxicol. Chem., 29, 730–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hill A.B. (1965)The environment and disease: association or causation?Proc. R. Soc. Med., 58, 295–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rusyn I., et al. (2012)Mechanistic considerations for human relevance of cancer hazard of di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate. Mutat. Res., 750, 141–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Harrison S., et al. (2017)The albatross plot: a novel graphical tool for presenting results of diversely reported studies in a systematic review. Res. Synth. Methods, 8, 281–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Harrison S., et al. (2017)Does milk intake promote prostate cancer initiation or progression via effects on insulin-like growth factors (IGFs)? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Causes Control, 28, 497–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Goodson W.H., III, et al. (2015)Assessing the carcinogenic potential of low-dose exposures to chemical mixtures in the environment: the challenge ahead. Carcinogenesis, 36, S254–S296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. National Academy of Science(2017)Using 21st Century Science to Improve Risk-Related Evaluations. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Smith A.M., et al. (2017)2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a meta-analysis accounting for exposure levels. Ann. Epidemiol., 27, 281–289.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kleinstreuer N.C., et al. (2014)Phenotypic screening of the ToxCast chemical library to classify toxic and therapeutic mechanisms. Nat. Biotechnol., 32, 583–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kavlock R., et al. (2012)Update on EPA’s ToxCast program: providing high throughput decision support tools for chemical risk management. Chem. Res. Toxicol., 25, 1287–1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. National Academy of Science(2007)Toxicity Testing in the 21st Century: A Vision and A Strategy. National Academies Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.