Abstract

Menopause before 45 years of age affects roughly 5%–10% of women and is associated with a higher risk of adverse health conditions. Although smoking may increase the risk of early menopause, evidence is inconsistent, and data regarding smoking amount, duration, cessation, associated risks, and patterns over time are scant. We analyzed data of 116,429 nurses from the Nurses’ Health Study II from 1989 through 2011 and used Cox proportional hazards models to estimate hazard ratios adjusted for confounders. Compared with never-smokers, current smokers (hazard ratio (HR) = 1.90, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.71, 2.11) and former smokers (HR = 1.10, 95% CI: 1.00, 1.21) showed an increased risk of early menopause. Increased risks were observed among women who reported current smoking for 11–15 pack-years (HR = 1.72, 95% CI: 1.36, 2.18), 16–20 pack-years (HR = 1.72, 95% CI: 1.38, 2.14), and more than 20 pack-years (HR = 2.42, 95% CI: 2.11, 2.77). Elevated risk was observed in former smokers who reported 11–15 pack-years (HR = 1.29, 95% CI: 1.07, 1.55), 16–20 pack-years (HR = 1.42, 95% CI: 1.13, 1.79), or more than 20 pack-years (HR = 1.54, 95% CI: 1.23, 1.93). Women who smoked 10 or fewer cigarettes/day but quit by age 25 had comparable risk to never-smokers (HR = 1.03, 95% CI: 0.91, 1.17). A dose-response relationship between smoking and early natural menopause risk, as well as reduced risk among quitters, may provide insights into the mechanisms of cigarette smoking in reproductive health.

Keywords: cigarette smoking, longitudinal cohort, menopause, ovarian function

Early menopause, described as cessation of ovarian function, before the age of 45 affects roughly 5%–10% of women in Western populations (1, 2). Research suggests that women who experience early menopause are at increased risk for premature mortality, cognitive decline, osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, and other adverse health outcomes (3–6). Women commonly experience declining fertility during the 10 years leading up to natural menopause. For women with early menopause, this may have substantial consequences for family planning, particularly with the increasing tendency to delay childbearing into the later reproductive years (1, 7). Genetic factors do not fully account for the timing of menopause, and emerging research suggests that modifiable factors may play an important role in ovarian aging (8–15).

Lifestyle factors such as smoking have been observed to be related to timing of menopause. Cigarette smoking may impact ovarian aging and follicle reserve by influencing gonadotropins and sex steroids and may also have toxic effects on ovarian germ cells (16). Current smoking is associated with earlier age at menopause in several populations (10, 11, 15–22). Epidemiologic studies of smoking and early menopause generally suggest increased risk (23–26), though not uniformly (27–29), and largely rely upon retrospective smoking reports (30, 31). Moreover, less is known regarding the relationship of the duration, amount, and history of smoking with the risk of early natural menopause; additional studies have been suggested to fill this gap (29, 31).

In the present study, we describe the analysis of the relation between cigarette smoking and risk of early natural menopause in women from the Nurses’ Health Study II (NHSII). The large cohort size and extensive longitudinal data collection allow for a robust evaluation of the associations of cigarette smoking status, duration, amount, and history with risk of early natural menopause. We hypothesized that there is a dose-dependent relation of both duration and amount smoked with risk of early natural menopause, as well as a lower risk among former smokers compared with current smokers.

METHODS

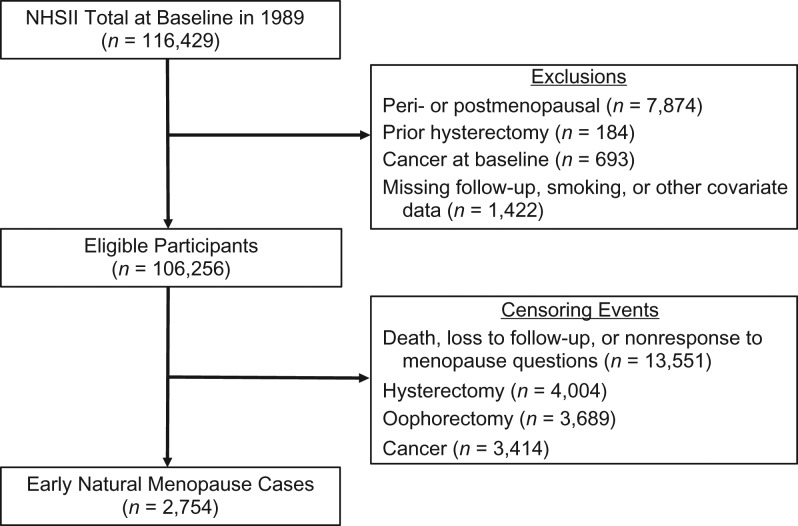

The NHSII is a prospective study of 116,429 female US registered nurses who were 25–42 years old in 1989 when they responded to a mailed baseline questionnaire. Information regarding lifestyle behaviors and medical conditions has been collected through biennial mailed questionnaires. The cumulative follow-up rate over time has been at least 89%. For the current analysis, exclusion criteria included not being premenopausal at baseline (n = 7,874), prior hysterectomy or oophorectomy at baseline (n = 184), cancer at baseline (n = 693), missing data on smoking or covariates (n = 127), or not participating beyond 1989 (n = 1,295), which resulted in a final sample of 106,256 women (Figure 1). The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of participants selection, Nurses’ Health Study II (NHSII), 1989–2011. Of the 116,429 participants at baseline in 1989, a total of 106,256 were included in the analytic sample followed up to 2011 for incident early natural menopause (n = 2,754).

Outcome assessment

Biennial questionnaires included questions regarding whether the menstrual periods of participants had ceased permanently. Among those who reported that their menstrual periods had ceased, participants were asked to indicate the age at cessation and whether cessation occurred naturally or was related to surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy. Information regarding use of replacement sex hormones was collected as well. We identified cases of early menopause as women who reported natural menopause before the age of 45 years. For a small number of women who reported being postmenopausal on 1 questionnaire and subsequently reported being premenopausal, age at menopause was that after which periods had been absent for 12 months or more and continued to be absent for 3 or more consecutive questionnaires. Premature menopause was defined as natural menopause before the age of 40 years.

Cigarette smoking

Cigarette smoking was assessed at baseline in 1989 and continued through 2013. The baseline questionnaire included questions about the age at which women started smoking, as well as the average number of cigarettes smoked per day at <15, 15–19, 20–24, 25–29, and 30–35 years of age. Women who reported lifetime smoking of 20 or more packs of cigarettes were asked about their current smoking status and if they had quit smoking within the past year. Current and former smokers reported the average number of cigarettes smoked per day (1–4, 5–14, 15–24, 25–34, 35–44, or ≥45). Subsequent biennial questionnaires included questions regarding current smoking status, the average number of cigarettes smoked per day, and the age at which those who stopped smoking quit. Updated smoking status was used to calculate duration of smoking; information regarding duration and average cigarettes smoked per day was used to calculate pack-years of smoking to date.

Covariates

Baseline questionnaires in 1989 collected data on information such as current age, height, weight, ethnicity, and age at menarche. Throughout follow-up, information was collected to update factors such as weight, parity, oral contraceptive use, breastfeeding, and hormone therapy use. Baseline height and updated weight were used to calculate body mass index (BMI) as weight (kg)/height (m)2 for each questionnaire cycle. Physical activity, which was assessed in 1991, 1997, 2001, 2005, and 2009, was defined as the average time spent weekly performing specific activities (e.g., walking, running, and biking) and was used to calculate metabolic equivalent task-hours per week (32).

Semiquantitative food frequency questionnaires were completed every 4 years starting in 1991. These questionnaires assessed intake of 131 foods, beverages, and supplements (33–35) and asked participants to estimate how often they consumed specific substances on average over the preceding year. They have been previously assessed for validity (35). Frequency of consumption was reported as one of the following: less than 1 serving/month; 1–3 servings/month; 1 serving/week; 2–4 servings/week; 5–6 servings/week; 1 serving/day; 2–3 servings/day; 4–5 servings/day; or 6 or more servings/day. Average use and dosage of multivitamins and supplements were assessed every 2 years, and were used to estimate the intake of each nutrient from supplement sources. Nutrient intake was adjusted for total energy using the residual method (36).

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics were evaluated according to baseline smoking status. Categorical variables were compared by χ2 tests and age-adjusted means were compared using generalized linear models. These comparisons were used to evaluate relations of a priori identified potential confounding factors with smoking to aid in model specification for multivariable models.

Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate hazard ratios for early menopause related to cigarette smoking. Assessed smoking behaviors included smoking status (current, past, never), a composite variable that combined smoking status and duration of smoking (never, 1–5, 6–10, 11–15, 16–20, and >20 years), and a composite variable that combined smoking status and amount of smoking (never, 1–5, 6–10, 11–15, 16–20, and >20 pack-years). For categorical smoking variables, tests for trend were performed by specifying smoking category as a continuous variable. Accrual of follow-up (in months) began on the date of return of the 1989 questionnaire and continued until report of age 45 years, menopause, or the end of follow-up in June 2011, whichever occurred first. Hysterectomy, oophorectomy and other medical causes of menopause before menopause were considered censoring events. Analyses were stratified on the basis of age and questionnaire cycle. Age-adjusted models were run and potential confounding addressed using multivariable models that were adjusted for a priori potential confounders that were observed to be related to smoking status. Risk of menopause before 40 years of age was assessed similarly. In sensitivity analyses, models that excluded women who reported autoimmune conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and multiple sclerosis were run. Additionally, models that stratified by BMI were run to assess homogeneity of the association across BMI categories.

We assessed patterns of smoking between the early teens and 35 years of age and their relation with early natural menopause. Latent class analysis was performed using SAS PROC TRAJ (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina) and examined self-reported age-specific average daily cigarettes among those that reported current or former smoking. Models were run that varied the number of latent classes; on the basis of model fit, 4 classes were specified. Never smokers were assigned to an additional class in which the average number of daily cigarettes was fixed at zero. Relations between smoking patterns and incident early menopause were evaluated by Cox proportional hazards models, both unadjusted and with adjustment for previously noted covariates. To further evaluate the relation of timing of smoking with incident early menopause, risk was compared between women by age at quitting within strata of pack-years of smoking, with never smokers as the reference group. Analysis was conducted with SAS, version 9.3 or version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics are shown for 69,881 (65.8%) women who reported never smoking, 22,619 (21.3%) who reported past smoking, and 13,756 (12.9%) who reported current smoking (Table 1). Mean age at baseline was lower for never smokers (33.7 years) than past smokers (35.0 years) and current smokers (34.4 years). Given the large sample size, statistically significant differences among groups were observed for most factors, though differences tended to be small in magnitude. For example, age-adjusted mean age at menarche varied between groups (P < 0.0001), though by less than 0.01 years. Small to moderate differences were observed for physical activity, parity, and race. Those who reported never having smoked had lower daily alcohol consumption (2.2 g/day) then former smokers (4.0 g/day) and current smokers (5.0 g/day). Current smokers had lower parity and shorter durations of breastfeeding, even when restricted to only parous women (data not shown). Vegetable protein consumption, vitamin D and calcium (total, dietary, dairy, and supplemental) were also lowest in those who reported current smoking status.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Women in the Study Sample (n = 106,256), by Smoking Statusa, Nurses’ Health Study II, 1989–2011b

| Characteristic | Smoking Status at Baseline | P Valuec | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never (n = 69,881; 65.8%) |

Past (n = 22,619; 21.3%) |

Current (n = 13,756; 12.9%) |

|||||

| Mean (SE) | % | Mean (SE) | % | Mean (SE) | % | ||

| Age, years | 33.7 (0.02) | 35.0 (0.03) | 34.4 (0.04) | <0.0001 | |||

| BMId | 24.0 (0.02) | 24.0 (0.03) | 24.0 (0.04) | 0.9 | |||

| Physical activity, MET-hours/week | 28.4 (0.26) | 29.6 (0.46) | 26.6 (0.59) | <0.0001 | |||

| Alcohol consumption, g/day | 2.2 (0.02) | 4.0 (0.04) | 5.0 (0.05) | <0.0001 | |||

| Duration of OC use, months | 40.2 (0.17) | 50.2 (0.30) | 53.8 (0.38) | <0.0001 | |||

| Age at menarche, years | 12.4 (0.01) | 12.4 (0.01) | 12.4 (0.01) | <0.01 | |||

| Parity | 1.4 (0.01) | 1.4 (0.01) | 1.3 (0.01) | <0.0001 | |||

| Breastfeeding duration, months | 13.9 (0.06) | 12.8 (0.11) | 8.8 (0.15) | <0.0001 | |||

| Vegetable protein (% of diet) | 5.0 (0.01) | 5.1 (0.01) | 4.7 (0.01) | <0.0001 | |||

| Vitamin D (IU/day) | |||||||

| Total (energy adjusted) | 393 (1.1) | 400 (1.9) | 354 (2.5) | <0.0001 | |||

| Dietary (energy adjusted) | 255 (0.5) | 259 (0.9) | 230 (1.2) | <0.0001 | |||

| Dairy (energy adjusted) | 133 (0.4) | 129 (0.8) | 118 (1.0) | <0.0001 | |||

| Supplemental | 137 (0.9) | 141 (1.6) | 124 (2.1) | <0.0001 | |||

| Calcium, mg/day | |||||||

| Total (energy adjusted) | 1,025 (1.8) | 1,036 (3.1) | 940 (4.1) | <0.0001 | |||

| Dietary (energy adjusted) | 892 (1.3) | 903 (2.2) | 831 (2.9) | <0.0001 | |||

| Dairy (energy adjusted) | 584 (1.3) | 583 (2.3) | 528 (2.9) | <0.0001 | |||

| Supplemental | 133 (1.3) | 133 (2.2) | 108 (2.9) | <0.0001 | |||

| Racee | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 92.9 | 96.4 | 95.4 | ||||

| Asian | 2.6 | 0.7 | 0.8 | ||||

| Other | 4.5 | 2.9 | 3.7 | ||||

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; IU, international unit; MET, metabolic equivalent of task; OC, oral contraceptive; SE, standard error.

a All comparisons other than age at baseline were adjusted for age.

b The study sample included women in the Nurses’ Health Study II who were premenopausal, at risk of early natural menopause, and free of cancer and for whom data on smoking status at baseline were available.

c P values from χ2 test or general linear models as appropriate.

d Weight (kg)/height (m)2.

e Age-adjusted estimates from general linear models of percent of each race category.

Results of Cox proportional hazards models, including a total of 2,754 incident early natural menopause cases that were observed during 1,453,023 person-years of follow-up, are shown in Table 2. Similar to models that were adjusted only for age, in multivariable models that were adjusted for possible confounders, current smoking was associated with a nearly 2-fold increase in risk compared with never smokers (hazard ratio (HR) = 1.90, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.71, 2.11) and past smoking status was associated with a smaller increase in risk (HR = 1.10, 95% CI: 1.00, 1.21). Former smokers who reported having smoked for more than 15 years were observed to have increased risk of early menopause (HR = 1.31, 95% CI: 1.14, 1.50). Among current smokers, the risk for those who reported more than 15 years of smoking was substantially higher than that of past and never smokers (HR = 1.97, 95% CI: 1.77, 2.20). Increased risk was associated with increasing cumulative pack-years of smoking among both past and current smokers (P tor trend < 0.0001 for both). Among past smokers, the risk for those with 10 or fewer pack-years of smoking were comparable to that of never smokers, whereas increased risks were observed for past smokers with 11–15 pack-years (HR = 1.29, 95% CI: 1.07, 1.55), 16–20 pack-years (HR = 1.42, 95% CI: 1.13, 1.79), and 20 or more pack-years (HR = 1.54, 95% CI: 1.23, 1.93). Among current smokers, increasing risk was observed for women who smoked at least 6–10 pack-years (HR = 1.43, 95% CI: 1.07, 1.90) and the risk for women who smoked at least 20 pack-years was more than twice that of never smokers (HR = 2.42, 95% CI: 2.11, 2.77). In analyses that excluded women with autoimmune conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus (n = 960), rheumatoid arthritis (n = 4,479), and multiple sclerosis (n = 1,308), estimates were nearly identical to those of the main analysis (results not shown).

Table 2.

Hazard Ratios for Risk of Early Natural Menopause by Cigarette Smoking, Nurses’ Health Study II, 1989–2011

| Cigarette Smoking Category | No. of Cases | No. of Person-Years | HRa | Adjusted HRb | 95% CI | P Valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Never smoker | 1,624 | 1,016,980 | 1.00 | 1.00 | Referent | |

| Past smoker | 632 | 303,458 | 1.09 | 1.10 | 1.00, 1.21 | |

| Current smoker | 498 | 132,585 | 1.98 | 1.90 | 1.71, 2.11 | |

| Duration of smoking by smoking status, years | ||||||

| Past | <0.001 | |||||

| 1–14 | 395 | 218,860 | 0.99 | 1.01 | 0.90, 1.13 | |

| ≥15 | 237 | 84,599 | 1.32 | 1.31 | 1.14, 1.50 | |

| Current | <0.0001 | |||||

| 1–14 | 38 | 24,477 | 1.38 | 1.36 | 0.98, 1.88 | |

| ≥15 | 460 | 108,108 | 2.05 | 1.97 | 1.77, 2.20 | |

| Pack-years of smoking by smoking status | ||||||

| Past | <0.0001 | |||||

| 1–5 | 209 | 120,801 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.84, 1.12 | |

| 6–10 | 134 | 80,409 | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.74, 1.06 | |

| 11–15 | 125 | 49,238 | 1.28 | 1.29 | 1.07, 1.55 | |

| 16–20 | 80 | 26,648 | 1.43 | 1.42 | 1.13, 1.79 | |

| >20 | 84 | 26,364 | 1.56 | 1.54 | 1.23, 1.93 | |

| Current | <0.0001 | |||||

| 1–5 | 22 | 14,458 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.65, 1.51 | |

| 6–10 | 49 | 22,934 | 1.47 | 1.43 | 1.07, 1.90 | |

| 11–15 | 76 | 25,763 | 1.78 | 1.72 | 1.36, 2.18 | |

| 16–20 | 87 | 24,045 | 1.80 | 1.72 | 1.38, 2.14 | |

| >20 | 264 | 45,385 | 2.53 | 2.42 | 2.11, 2.77 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

a Adjusted for age only.

b Adjusted for alcohol consumption (<0.1, 0.1–10.0, 10.1–30.0, or >30.0 g/day), parity (0, 1–2, or ≥3), duration of breastfeeding (<1.0, 1.0–3.0, 3.1–6.0, 6.1–12.0, 12.1–18.0, 18.1–24.0, 24.1–36.0, or >36.0 months), percentage of calories from vegetable protein (quintiles), age at menarche (years), body mass index (American Diabetes Association categories), and dairy and supplemental sources of vitamin D (quintiles).

c P value for tests of trend from regression analyses with category as a continuous predictor.

Results of latent class analysis and the related assessment of smoking pattern and risk of early natural menopause are shown in Figure 1 and Table 3. Using retrospectively-reported average smoking (cigarettes/day), 5 groups were identified. Additionally, 4 patterns of smoking between women under 15 years and 35 years of age were determined from latent class models in addition to never smokers, the largest of the groups (Figure 1). On the basis of smoking patterns, the 4 groups of smokers can be described as 1) light smokers who quit by 35 years of age, 2) women who reported heavier smoking through 30 years of age and quit by age 35 years, 3) women who smoked between 5–14 and 15–24 cigarettes per day from age 20 years through 35 years, and 4) women who smoked between 15–24 and 25–34 cigarettes per day through age 35 years.

Table 3.

Hazard Ratios for Risk of Early Natural Menopause Risk by Pattern of Smoking Behavior Between Early Teenage Years and Age 35 Years, Nurses’ Health Study II, 1989–2011

| Pattern | No. of Casesa | No. of Person-Yearsa | HRb | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never smokers | 1,627 | 1,021,184 | 1.00 | Referent |

| Quitters; former light smokers | 298 | 158,937 | 1.03 | 0.91, 1.17 |

| Quitters; former moderate to heavy smokers | 118 | 49,783 | 1.27 | 1.05, 1.53 |

| Moderate smokers though age 35 years | 417 | 123,037 | 1.64 | 1.47, 1.84 |

| Heavy smokers through age 35 years | 214 | 59,265 | 1.80 | 1.56, 2.08 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

a Totals do not sum to 2,754 cases and 1,453,023 person-years because of missing data on smoking behavior between early teens and 35 years of age.

b Adjusted for alcohol consumption (<0.1, 0.1–10.0, 10.1–30.0, or >30.0 g/day), parity (0, 1–2, ≥3), duration of breastfeeding (<1.0, 1.0–3.0, 3.1–6.0, 6.1–12.0, 12.1–18.0, 18.1–24.0, 24.1–36.0, or >36.0 months), percentage of calories from vegetable protein (quintiles), age at menarche (years), body mass index (American Diabetes Association categories), and dairy and supplemental sources of vitamin D (quintiles).

In models that evaluated the risk of early menopause related to smoking pattern, the highest risks were observed among women who continued smoking through age 35 years, for both moderate smokers (HR = 1.64, 95% CI: 1.47, 1.84) and those in the group with the highest smoking amount (HR = 1.80, 95% CI: 1.56, 2.08). Women who quit by age 25 years and whose peak average cigarettes smoked was less than a pack per day had no increase in risk of early menopause (HR = 1.03, 95% CI: 0.91, 1.17). In contrast, women who quit by age 35 years and had smoked more heavily had a moderate and statistically significant increased risk of early natural menopause (HR = 1.27, 95% CI: 1.05, 1.53).

Results of models that compared never smokers with past and current smokers by age at quitting within strata of total pack-years are shown in Table 4. Among past smokers who smoked 5–10 pack-years, risk was comparable to never smokers, whereas increased risk was observed among women who reported currently smoking 5–10 pack-years (HR = 1.45, 95% CI: 1.09, 1.94). Among women who smoked 11–15 pack-years and quit, significantly increased risk was observed only among women who had not quit before age 40 years (HR = 2.12, 95% CI: 1.24, 3.63). Lower risk related to earlier ages of quitting was observed for those who quit before age 40 years (P for trend < 0.001), but individual estimates were not statistically significant. Among women who quit smoking after 16–20 pack-years, risks were comparable across ages at quitting and was higher compared with never smokers.

Table 4.

Risk of Early Natural Menopause by Age at Quitting Within Strata of Pack-Years of Smoking, Nurses’ Health Study II, 1989–2011

| Total Pack-Years of Smoking and Age at Quitting | HR | 95% CI | Adjusted HRa | 95% CI | P for Trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never smokers | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | |

| 5–10 pack-years | 0.23 | ||||

| <25 years | 0.82 | 0.60, 1.12 | 0.86 | 0.62, 1.17 | |

| 25–29 years | 0.86 | 0.63, 1.17 | 0.87 | 0.64, 1.19 | |

| 30–34 years | 1.12 | 0.79, 1.57 | 1.12 | 0.80, 1.58 | |

| 35–39 years | 0.75 | 0.43, 1.33 | 0.74 | 0.42, 1.31 | |

| 40–44 years | 0.76 | 0.31, 1.82 | 0.74 | 0.31, 1.80 | |

| Smoking at 45 years | 1.47 | 1.10, 1.96 | 1.45 | 1.09, 1.94 | |

| 11–15 pack-years | <0.001 | ||||

| <25 years | 1.11 | 0.67, 1.85 | 1.14 | 0.69, 1.91 | |

| 25–29 years | 1.13 | 0.82, 1.55 | 1.14 | 0.82, 1.57 | |

| 30–34 years | 1.28 | 0.91, 1.79 | 1.27 | 0.90, 1.78 | |

| 35–39 years | 1.46 | 0.94, 2.25 | 1.45 | 0.94, 2.24 | |

| 40–44 years | 2.20 | 1.28, 3.75 | 2.12 | 1.24, 3.63 | |

| Smoking at 45 years | 1.77 | 1.41, 2.24 | 1.74 | 1.37, 2.20 | |

| 16–20 pack-years | <0.001 | ||||

| <25 years | –b | –b | |||

| 25–29 years | 1.57 | 1.01, 2.45 | 1.62 | 1.04, 2.53 | |

| 30–34 years | 1.34 | 0.94, 1.92 | 1.34 | 0.94, 1.93 | |

| 35–39 years | 1.82 | 1.21, 2.73 | 1.76 | 1.17, 2.65 | |

| 40–44 years | 1.45 | 0.74, 2.80 | 1.41 | 0.72, 2.73 | |

| Smoking at 45 years | 1.74 | 1.40, 2.16 | 1.67 | 1.34, 2.08 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

a Adjusted for alcohol consumption (<0.1, 0.1–10.0, 10.1–30.0, or >30.0 g/day), parity (0, 1–2, ≥3), duration of breastfeeding (<1.0, 1.0–3.0, 3.1–6.0, 6.1–12.0, 12.1–18.0, 18.1–24.0, 24.1–36.0, or >36.0 months), percentage of calories from vegetable protein (quintiles), age at menarche (years), body mass index (American Diabetes Association categories), and dairy and supplemental sources of vitamin D (quintiles).

b Inestimable because of inadequate numbers of women reporting 16–20 pack-years of smoking and quitting before age 25 years.

Results of models of premature menopause among the 300 women who experienced natural menopause before age 40 years followed a similar pattern to those of early menopause, though estimates were generally attenuated, with small case numbers in categories of amount and duration (results not shown). Compared with never smokers, current smoking status was associated with a 50% increased risk of premature menopause in adjusted models (HR = 1.52, 95% CI: 1.12, 2.06). In contrast, risk of premature menopause among former smokers was not meaningfully different from that of never smokers (HR = 1.07, 95% CI: 0.82, 1.40).

DISCUSSION

Smoking has long been considered to be related to earlier age at menopause, but uncertainty about causal links with the risk of early menopause has persisted because of a relative lack of information regarding duration and amount of smoking, as well as past smoking habits. To our knowledge, this is the largest study of cigarette smoking and early natural menopause to date. We considered data from up to 20 years of follow-up from 106,256 NHSII participants who were premenopausal at baseline, among whom 2,754 experienced early natural menopause during follow-up. We observed a nearly 2-fold increased risk associated with current smoking status compared with women who reported never having smoked. We observed a dose-response increasing risk related to current smoking amount and duration, with the highest risks observed among current heavy smokers. A smaller increased risk was observed among former heavy smokers. Among women who reported past light smoking, no increased risk was observed. In addition, we observed increased risk of natural menopause occurring before age 40 years among current smokers.

Our observation of increased risk of early menopause related to current smoking status is consistent with the majority of prior studies, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses that have evaluated this relation. A meta-analysis from 2012 that included 11 studies with a total of approximately 50,000 women suggested a 43% increased risk of menopause before age 50 years when comparing current smokers to nonsmokers (30). A systematic review of smoking and age at menopause that included 93 studies reported an earlier age at menopause among current smokers compared with nonsmokers, though no estimate was presented and no information was provided on risk of early menopause (29). The authors noted that insufficient data regarding the impact of the quantity of cigarettes smoked and historical smoking habits prevented conclusions regarding how these aspects of smoking are related to menopausal timing. In addition, most prior studies have been cross-sectional; a need for large prospective studies of the relation between smoking and age at menopause has been described (29, 31).

In a recent prospective study, smoking and early natural menopause was evaluated among 7,223 participants of the Mater-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy cohort. Smoking was assessed at baseline, 7 years, 14 years, and study completion at 21 years among 3,545 women who completed follow-up, among whom early natural menopause was experienced by 144 women (37). Women who smoked more than 20 cigarettes per day at baseline, those who reported smoking 20 or more cigarettes per day at the 14-year follow-up, and those who reported being current smokers at the end of the 21 year observation period for the study had an approximately 50% higher risk of early menopause than women who never smoked. A smaller increase in risk was observed in those who smoked less than 20 cigarettes per day and no increased risk was observed for former smokers. The authors concluded that risk rises with increasing quantity, but returns to that of nonsmokers among women who quit, contrary to our findings in the present study.

Despite consistent risk estimates for current versus never smoking, the role of amount, duration, and history of smoking has been unclear (29, 31). Prior studies of risk in former smokers are limited and results have been inconsistent. Some have observed elevated risk among former smokers (20, 38–40). Others have found no association (13, 19, 41–47), and some have suggested that neither past smoking habits nor duration are related to risk (43, 47). We observed dose-response relations between smoking and risk of early menopause, with the most elevated risks among current smokers with more than 20 pack-years of smoking. We observed no increased risk among past smokers with the lowest smoking quantity and duration; however, risk was elevated among former smokers who smoked more than 10 pack-years. Further, women who quit smoking in their 30s had lower risk of developing early menopause than women who quit in their early 40s. Our results suggest that risk does not return to that of never smokers for women who quit, but is most pronounced among women who continue smoking late into their reproductive years. Our analysis included more than 20,000 former smokers. Because of its sample size, the NHSII provides a unique opportunity for assessment risk among of women who quit smoking.

Multiple mechanisms by which cigarette smoking may influence timing of menopause have been proposed, including acute effects on levels of gonadotropin and sex steroids, as well as direct toxic effects on ovarian follicles (16). Components of cigarette smoke including nicotine and polycyclic hydrocarbons block aromatase conversion of androgens into estrogens in animal models (48), which may lower blood levels of estrogen (49) and peak luteinizing hormone (48). This effect may be exacerbated by the effects of smoke on cytochrome P-450 steroid metabolism as well (50). Our observation of increased risk of early menopause among former smokers and a dose response related to quantity and duration of past cigarette smoking is consistent with a direct effect of smoking on follicle loss. Compared with nonsmokers, smokers have been observed to have lower levels of anti-Müllerian hormone (51), a glycoprotein produced by small antral and pre-antral follicles (52). This evidence provides further support for direct effects of smoking on ovarian germ cells. Our observation of the increased risk of menopause before age 40 years associated with current smoking suggests a similar role of smoking. Despite uncertainty regarding the relation between the etiologies of premature ovarian insufficiency and early menopause, studies of genetic influences suggest these overlap (53, 54).

The NHSII is a prospective study with 20 years of follow-up. Many prior analyses of the relation of smoking with timing of menopause have been restricted to cross-sectional studies and/or only retrospectively-reported smoking. In contrast, our analysis included longitudinally reported cigarette smoking habits throughout follow-up. In addition, the large sample size and extensive covariate assessment in the NHSII help to address possible confounding and/or effect modification. Results of analyses restricted to women with normal BMI were similar to results in the full cohort, and effect estimates were highly consistent across all 4 BMI categories (data not shown). Censoring due to hysterectomy (n = 4,004) and oophorectomy (n = 3,689) was unassociated with baseline smoking status, and mitigates the potential for bias related to competing events.

Nevertheless, some limitations are of note. We utilized self-reported menopausal age and smoking status, as laboratory measures were not feasible in a study of this size. A study of 6,591 women in the comparable Nurses’ Health Study suggests that self-reported menopausal status is reproducible and valid. Among women who were premenopausal in 1976 and who reported having natural menopause on the 1978 questionnaire, 82% reported their age at menopause to within 1 year on the following 2 questionnaires (55). Given the prospective study design, misclassification of menopausal age is expected to be nondifferential by smoking status. This would likely bias estimates towards the null; however, to the extent that accuracy of report of menopausal may be related to smoking, bias otherwise is possible.

Self-reported smoking has been shown to be largely accurate in various study populations (56–58). Further, use of prospective assessment of smoking habits is likely to minimize reporting errors, and, as with menopausal timing, misclassification most likely represents a bias toward the null. However, for women who quit smoking before 1989, smoking information was collected retrospectively, though before menopause. Baseline smoking prevalence in the NHSII was slightly lower than among women aged 25–44 years in the general US population (59). Additionally, the NHSII has minimal variability in race or ethnicity and income. Generalizability of our findings depends in part on the mechanism of smoking being conserved across subgroups.

This large prospective analysis provides support for a dose-response relation between cigarette smoking and risk of early menopause, primarily among current smokers but also among past smokers. As cigarette smoking is well-established to adversely impact risk of many disease and health outcomes, our findings do not suggest change to current public health policy. The observation of minimal to no increased risk of early natural menopause among women who quit early in their reproductive lifespan compared with never smokers adds to the body of evidence that support the benefits of quitting smoking. Further, these findings may help to resolve uncertainty regarding relations of risk of early menopause with smoking amount and among former smokers, and provide further insights into the mechanisms of cigarette smoke on reproductive health.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Author affiliations: Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, School of Public Health and Health Sciences, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Amherst, Massachusetts (Brian W. Whitcomb, Alexandra C. Purdue-Smithe, Kathleen L. Szegda, Maegan E. Boutot, Susan E. Hankinson, Elizabeth R. Bertone-Johnson); Channing Division of Network Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts (Susan E. Hankinson, Bernard Rosner, Walter C. Willett, A. Heather Eliassen); and Division of Preventive Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts (JoAnn E. Manson).

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant UM-1-CA-176726 and grant R01-HD-078517).

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Abbreviations

- BMI

body mass index

- CI

confidence interval

- HR

hazard ratio

- NHSII

Nurses’ Health Study II

REFERENCES

- 1. Shuster LT, Rhodes DJ, Gostout BS, et al. Premature menopause or early menopause: long-term health consequences. Maturitas. 2010;65(2):161–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Coulam CB, Adamson SC, Annegers JF. Incidence of premature ovarian failure. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;67(4):604–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wellons M, Ouyang P, Schreiner PJ, et al. Early menopause predicts future coronary heart disease and stroke: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Menopause. 2012;19(10):1081–1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. van Der Voort DJ, van Der Weijer PH, et al. Early menopause: increased fracture risk at older age. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14(6):525–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fauser BC. Trilogy 8: Premature ovarian failure and perimenopause. Female health implications of premature ovarian insufficiency In: Tarlatzis BC, Bulun SE, eds. Proceedings of the International Federation of Fertility Societies 21st World Congress on Fertility and Sterility and the 69th Annual Meeting of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Boston, MA: Craftsman Printing, Inc.; 2013:137–138. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bleil ME, Gregorich SE, McConnell D, et al. Does accelerated reproductive aging underlie premenopausal risk for cardiovascular disease? Menopause. 2013;20(11):1139–1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Broekmans FJ, Soules MR, Fauser BC. Ovarian aging: mechanisms and clinical consequences. Endocr Rev. 2009;30(5):465–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Simpson JL. Trilogy 8: Premature ovarian failure and perimenopause. Genetics of premature ovarian failure In: Tarlatzis BC, Bulun SE, eds. Proceedings of the International Federation of Fertility Societies 21st World Congress on Fertility and Sterility and the 69th Annual Meeting of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Boston, MA: Craftsman Printing, Inc.; 2013:137–138. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Carwile JL, Willett WC, Michels KB. Consumption of low-fat dairy products may delay menopause. J Nutr. 2013;143(10):1642–1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bromberger JT, Matthews KA, Kuller LH, et al. Prospective study of the determinants of age at menopause. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145(2):124–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dorjgochoo T, Kallianpur A, Gao YT, et al. Dietary and lifestyle predictors of age at natural menopause and reproductive span in the Shanghai Women’s Health Study. Menopause. 2008;15(5):924–933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nagata C, Takatsuka N, Kawakami N, et al. Association of diet with the onset of menopause in Japanese women. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(9):863–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nagel G, Altenburg HP, Nieters A, et al. Reproductive and dietary determinants of the age at menopause in EPIC-Heidelberg. Maturitas. 2005;52(3–4):337–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Torgerson DJ, Thomas RE, Campbell MK, et al. Alcohol consumption and age of maternal menopause are associated with menopause onset. Maturitas. 1997;26(1):21–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yasui T, Hayashi K, Mizunuma H, et al. Factors associated with premature ovarian failure, early menopause and earlier onset of menopause in Japanese women. Maturitas. 2012;72(3):249–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cramer DW, Harlow BL, Xu H, et al. Cross-sectional and case-controlled analyses of the association between smoking and early menopause. Maturitas. 1995;22(2):79–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Emaus A, Dieli-Conwright C, Xu X, et al. Increased long-term recreational physical activity is associated with older age at natural menopause among heavy smokers: the California Teachers Study. Menopause. 2013;20(3):282–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gold EB, Crawford SL, Avis NE, et al. Factors related to age at natural menopause: longitudinal analyses from SWAN. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178(1):70–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gold EB, Bromberger J, Crawford S, et al. Factors associated with age at natural menopause in a multiethnic sample of midlife women. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153(9):865–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Palmer JR, Rosenberg L, Wise LA, et al. Onset of natural menopause in African American women. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):299–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Parazzini F, Pregetto Menopausa Italia Study Group . Determinants of age at menopause in women attending menopause clinics in Italy. Maturitas. 2007;56(3):280–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pokoradi AJ, Iversen L, Hannaford PC. Factors associated with age of onset and type of menopause in a cohort of UK women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(1):34.e1–34.e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Saraç F, Öztekin K, Çelebi G. Early menopause association with employment, smoking, divorced marital status and low leptin levels. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2011;27(4):273–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mikkelsen TF, Graff-Iversen S, Sundby J, et al. Early menopause, association with tobacco smoking, coffee consumption and other lifestyle factors: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Luborsky JL, Meyer P, Sowers MF, et al. Premature menopause in a multi-ethnic population study of the menopause transition. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(1):199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ortega-Ceballos PA, Morán C, Blanco-Muñoz J, et al. Reproductive and lifestyle factors associated with early menopause in Mexican women. Salud Publica Mex. 2006;48(4):300–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chang SH, Kim CS, Lee KS, et al. Premenopausal factors influencing premature ovarian failure and early menopause. Maturitas. 2007;58(1):19–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ashrafi M, Ashtiani SK, Malekzadeh F, et al. Factors associated with age at natural menopause in Iranian women living in Tehran. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;102(2):175–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Parente RC, Faerstein E, Celeste RK, et al. The relationship between smoking and age at the menopause: a systematic review. Maturitas. 2008;61(4):287–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sun L, Tan L, Yang F, et al. Meta-analysis suggests that smoking is associated with an increased risk of early natural menopause. Menopause. 2012;19(2):126–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lacey JV., Jr Smoking lowers the age at natural menopause among smokers and raises important questions. Menopause. 2012;19(2):119–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wolf AM, Hunter DJ, Colditz GA, et al. Reproducibility and validity of a self-administered physical activity questionnaire. Int J Epidemiol. 1994;23(5):991–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rimm E, Giovannucci EL, Stampfer MJ, et al. Reproducibility and validity of an expanded self-administered semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire among male health professionals. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135(10):1114–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Salvini S, Hunter DJ, Sampson L, et al. Food-based validation of a dietary questionnaire: the effects of week-to-week variation in food consumption. Int J Epidemiol. 1989;18(4):858–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Willett WC, Sampson L, Stampfer MJ, et al. Reproducibility and validity of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;122(1):51–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Willett WC. Nutritional Epidemiology. 2nd ed New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hayatbakhshs MR, Clavarino A, Williams GM, et al. Cigarette smoking and age of menopause: a large prospective study. Maturitas. 2012;72(4):346–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Adena MA, Gallagher HG. Cigarette smoking and the age at menopause. Ann Hum Biol. 1982;9(2):121–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lindquist O, Bengtsson C. Menopausal age in relation to smoking. Acta Med Scand. 1979;205(1–2):73–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Willett W, Stampfer MJ, Bain C, et al. Cigarette smoking, relative weight, and menopause. Am J Epidemiol. 1983;117(6):651–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Blanck HM, Marcus M, Tolbert PE, et al. Time to menopause in relation to PBBs, PCBs, and smoking. Maturitas. 2004;49(2):97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Brett KM, Cooper GS. Associations with menopause and menopausal transition in a nationally representative US sample. Maturitas. 2003;45(2):89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cooper GS, Sandler DP, Bohlig M. Active and passive smoking and the occurrence of natural menopause. Epidemiology. 1999;10(6):771–773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. de Vries E, den Tonkelaar I, van Noord PA, et al. Oral contraceptive use in relation to age at menopause in the DOM cohort. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(8):1657–1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hardy R, Kuh D, Wadsworth M. Smoking, body mass index, socioeconomic status and the menopausal transition in a British national cohort. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29(5):845–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kato I, Toniolo P, Akhmedkhanov A, et al. Prospective study of factors influencing the onset of natural menopause. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(12):1271–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. van Asselt KM, Kok HS, van Der Schouw YT, et al. Current smoking at menopause rather than duration determines the onset of natural menopause. Epidemiology. 2004;15(5):634–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. McLean BK, Rubel A, Nikitovitch-Winer MB. The differential effects of exposure to tobacco smoke on the secretion of luteinizing hormone and prolactin in the proestrous rat. Endocrinology. 1977;100(6):1566–1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Barbieri RL, Gochberg J, Ryan KJ. Nicotine, cotinine, and anabasine inhibit aromatase in human trophoblast in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1986;77(6):1727–1733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tziomalos K, Charsoulis F. Endocrine effects of tobacco smoking. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2004;61(6):664–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Plante BJ, Cooper GS, Baird DD, et al. The impact of smoking on anti-Müllerian hormone levels in women aged 38 to 50 years. Menopause. 2010;17(3):571–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Weenen C, Laven JS, von Bergh AR, et al. Anti-Müllerian hormone expression pattern in the human ovary: potential implications for initial and cyclic follicle recruitment. Mol Hum Reprod. 2004;10(2):77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Perry JR, Corre T, Esko T, et al. A genome-wide association study of early menopause and the combined impact of identified variants. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22(7):1465–1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Schuh-Huerta SM, Johnson NA, Rosen MP, et al. Genetic variants and environmental factors associated with hormonal markers of ovarian reserve in Caucasian and African American women. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(2):594–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willet WC, et al. Reproducibility and validity of self-reported menopausal status in a prospective cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 1987;126(2):319–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Caraballo RS, Giovino GA, Pechacek TF, et al. Factors associated with discrepancies between self-reports on cigarette smoking and measured serum cotinine levels among persons aged 17 years or older third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153(8):807–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Patrick DL, Cheadle A, Thompson DC, et al. The validity of self-reported smoking: a review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(7):1086–1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Simard JF, Rosner BA, Michels KB. Exposure to cigarette smoke in utero: comparison of reports from mother and daughter. Epidemiology. 2008;19(4):628–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) Cigarette smoking among adults – United States, 1990. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1992;41(20);354–355, 361–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]