Abstract

Background

We report here the prognostic value of ploidy and digital tumour-stromal morphometric analyses using material from 2624 patients with early stage colorectal cancer (CRC).

Patients and methods

DNA content (ploidy) and stroma-tumour fraction were estimated using automated digital imaging systems and DNA was extracted from sections of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue for analysis of microsatellite instability. Samples were available from 1092 patients recruited to the QUASAR 2 trial and two large observational series (Gloucester, n = 954; Oslo University Hospital, n = 578). Resultant biomarkers were analysed for prognostic impact using 5-year cancer-specific survival (CSS) as the clinical end point.

Results

Ploidy and stroma-tumour fraction were significantly prognostic in a multivariate model adjusted for age, adjuvant treatment, and pathological T-stage in stage II patients, and the combination of ploidy and stroma-tumour fraction was found to stratify these patients into three clinically useful groups; 5-year CSS 90% versus 83% versus 73% [hazard ratio (HR) = 1.77 (95% confidence interval (95% CI): 1.13–2.77) and HR = 2.95 (95% CI: 1.73–5.03), P < 0.001].

Conclusion

A novel biomarker, combining estimates of ploidy and stroma-tumour fraction, sampled from FFPE tissue, identifies stage II CRC patients with low, intermediate or high risk of CRC disease specific death, and can reliably stratify clinically relevant patient sub-populations with differential risks of tumour recurrence and may support choice of adjuvant therapy for these individuals.

Keywords: colorectal cancer, ploidy, stroma fraction, prognosis

Key Message

A new marker panel, combination of DNA ploidy and stroma-tumour fraction, was able to stratify the patients with stage II colorectal carcinoma into three clinically viable risk groups with 5-year cancer-specific survival 90%, 83%, and 73%, respectively. The stage II patients with a prognosis similar to stage I patients might therefore avoid adjuvant treatment.

Introduction

Biomarkers are being used increasingly to select populations of cancer patients who are likely to benefit most from treatment and avoid life threatening toxicity [1, 2]. However, the dominant management decision in the adjuvant setting is whether any treatment should be offered at all, given its relatively marginal benefits [3]. For example, a 6-month postoperative course of 5-fluorouracil and folinic acid or capecitabine improves overall survival (OS) by around 3%–5% for patients with stage II or IIIA colorectal cancer. The vast majority (75%–80%) of these patients will be cured by surgery alone; 15%–20% will recur despite adjuvant chemotherapy; there is likely to be a chemotherapy associated death rate of 0.5%–1%; and 20% of patients will suffer significant side effects [4–7]. The risk–benefit ratio is therefore marginal, but would be positively skewed if it were possible to define a subgroup at higher risk of recurrence and cancer specific death.

Although clinically validated prognostic biomarkers would facilitate adjuvant therapeutic decisions, until recently, none have been sufficiently robust for routine clinical application. We recently reaffirmed the prognostic value of DNA mismatch repair (MMR) status in 1913 patients enrolled in the QUASAR trial [8] and identified those 12%–15% of MMR-deficient, stage II patients at a reduced risk of recurrence and in whom adjuvant therapy is not indicated [9, 10]. Similarly, a clinical argument has been presented for use of an RNA signature-based risk score to stratify T3 N0, MMR-proficient colorectal tumours [11]. A number of studies have shown that manually assessed stroma fraction is a prognostic marker in colorectal cancer (CRC) [12–15]. Further subdivision was investigated by Angell and Galon [16], who explored the prognostic impact of immune infiltrates.

The aim of the present study was to undertake morphometric and molecular analysis of a series of primary CRC specimens collected retrospectively from patients entered into a trial (QUASAR) of adjuvant therapy and two large observational cohorts to validate the combination of ploidy and stromal fraction as a potentially clinically useful prognostic marker.

Methods

QUASAR 2 study

A total of 1952 patients, who had undergone surgery for stage III/high risk stage II CRC, were randomly assigned to receive capecitabine alone, comprising a 3-week cycle of 1250 mg/m2 twice daily for 14 days followed by a 7 days break for a total of eight cycles, or the same in combination with bevacizumab, 7.5 mg/kg intravenous infusion over 90 minutes on day 1 of each 3-week cycle. The primary end point was 3-year disease-free survival (DFS) with OS a secondary end point.

The study was undertaken in accordance with the protocol, good clinical practice, the EU Directive 2001/20/EC and 2005/28/EC, and the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by West Midlands Research Ethics Committee, United Kingdom (REC reference: 04/MRE/11/18). An independent data safety monitoring committee carried out annual safety reviews. This trial is registered, number ISRCTN 4513315.

Gloucester cohort

The Gloucester Colorectal Cancer Study was carried out between 1988 and 1996 and recruited 1050 patients. A small proportion of the patients (7% among stage II and 15% among stage III) received adjuvant therapy. The prognostic impact of peritoneal involvement has been evaluated in the colonic and rectal cancers in this cohort previously [17, 18]. The Gloucestershire Local Research Ethics Committee, under reference 01/21G, approved the study.

Oslo University Hospital—Aker cohort

This cohort is a consecutive series of 578 stages I–III colorectal cancer patients treated at Oslo University Hospital—Aker, Norway, in the period 1993–2003. A minority of the patients received adjuvant therapy (1% among stage II and 30% among stage III patients). The prognostic impact of DNA ploidy and microsatellite instability (MSI) status has been reported in the same patient cohort previously [19, 20]. The study was carried out according to the Helsinki Declaration and approved by the Norwegian Regional Committees for Medical Research (REK; #1.2005.1629).

Tumour sampling

For analyses, the pathologist selected one tumour block deemed representative from each patient, and annotated the whole epithelial tumour region. Hence, no systematic selection was carried out.

DNA ploidy analysis

DNA ploidy analysis by image cytometry was carried out as previously reported [21].

Tumour-stroma fraction

The tumour-stroma fraction was measured on the histological images using developed proprietary software tools and analysis methods as described in supplementary methods, available at Annals of Oncology online. The method for automatically segmenting tumour-stroma in HE-stained tissue sections (Supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology) was developed in a separate dataset where a pathologist evaluated the segmentation results during development. The cutoff value for low and high stroma was taken from a previous study where stroma fraction was manually assessed [12].

Statistical analysis

All pathological and laboratory assessments were undertaken blind to the patients’ treatment allocation and clinical outcomes.

Five-year cancer-specific survival (CSS) was the end point common to all datasets and was used for the individual and pooled analyses. For QUASAR 2, survival time was calculated from date of randomisation. An event was defined as cancer death within 5 years. Observations were censored at death from other causes or at 5 years after randomisation, whichever occurred first. For the Gloucester and Aker datasets, survival time was calculated from surgery date.

For assessment of the prognostic value of variables, cancer-specific mortality rates over the follow-up period of 5 years were analysed. Only variables that were significant in univariate analyses in the pooled dataset were included in the multivariate analysis, with the exception of age. Estimated survival functions were compared using the Mantel-Cox log-rank test in univariate analysis of categorical variables and the Wald chi-squared test in multivariate analysis. Analyses were carried out using R version 3.1.3.

Results

Patient demography

The majority of patients had colon cancer (75%), median age of 68 years, a male preponderance (55% versus 45%), a majority of stage III patients (53% versus 39% stage II and 7% stage I), with stage II subjects having a higher proportion of MSI (18% versus 11%, Table 1). Stages II and III had more high stroma tumours compared with stage I (13% versus 7%, supplementary Tables S1A–C, available at Annals of Oncology online). All patients in the QUASAR 2 cohort received chemotherapy (capecitabine ± bevacizumab), whereas 1% of the Aker and 7% of the Gloucester stage II patients were treated with chemotherapy.

Table 1.

Distribution of relevant parameters

| Variables | QUASAR 2 | Gloucester | OUH-Aker | Pa | All hospitals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | <0.001b | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 64±10 | 70±11 | 70±12 | 68±11 | |

| Range | 27-88 | 28-94 | 30-94 | 27-94 | |

| Gender | 0.004 | ||||

| Male | 634 (58) | 510 (53) | 288 (50) | 1432 (55) | |

| Female | 458 (42) | 444 (47) | 290 (50) | 1192 (45) | |

| Tumor site | <0.001 | ||||

| Colon | 882 (85) | 641 (67) | 406 (70) | 1929 (75) | |

| Rectum | 158 (15) | 313 (33) | 172 (30) | 643 (25) | |

| Disease stage | <0.001 | ||||

| Stage I | 0 | 83 (9) | 112 (19) | 195 (7) | |

| Stage II | 394 (36) | 358 (38) | 277 (48) | 1029 (39) | |

| Stage III | 698 (64) | 513 (54) | 189 (33) | 1400 (53) | |

| pT stage | <0.001 | ||||

| pT1 | 17 (2) | 14 (1) | 27 (5) | 58 (2) | |

| pT2 | 70 (7) | 70 (7) | 103 (18) | 243 (9) | |

| pT3 | 569 (54) | 422 (44) | 414 (72) | 1405 (55) | |

| pT4 | 389 (37) | 447 (47) | 34 (6) | 870 (34) | |

| pN stage | <0.001 | ||||

| pN0 | 381 (36) | 442 (46) | 388 (67) | 1211 (47) | |

| pN1 | 489 (47) | 273 (29) | 152 (26) | 914 (35) | |

| pN2 | 181 (17) | 239 (25) | 37 (6) | 457 (18) | |

| Histological grade | <0.001 | ||||

| Well differentiated | 42 (4) | 141 (15) | 58 (10) | 241 (9) | |

| Moderately differentiated | 829 (80) | 516 (54) | 452 (79) | 1797 (70) | |

| Poorly differentiated | 160 (16) | 297 (31) | 63 (11) | 520 (20) | |

| Stroma | <0.001 | ||||

| Low | 986 (90) | 882 (92) | 415 (72) | 2283 (87) | |

| High | 106 (10) | 72 (8) | 163 (28) | 341 (13) | |

| Ploidy status | 0.75 | ||||

| Diploid | 326 (30) | 296 (31) | 182 (31) | 804 (31) | |

| Non-diploid | 766 (70) | 658 (69) | 396 (69) | 1820 (69) | |

| Ploidy and stroma | <0.001 | ||||

| Diploid and low stroma | 309 (28) | 286 (30) | 159 (28) | 754 (29) | |

| Diploid and high stroma | 17 (2) | 10 (1) | 23 (4) | 50 (2) | |

| Non-diploid and low stroma | 677 (62) | 596 (62) | 256 (44) | 1529 (58) | |

| Non-diploid and high stroma | 89 (8) | 62 (6) | 140 (24) | 291 (11) | |

| Ploidy and stroma 3 groups | <0.001 | ||||

| Diploid and low stroma | 309 (28) | 286 (30) | 159 (28) | 754 (29) | |

| Diploid and high stroma/non-diploid and low stroma | 694 (64) | 606 (64) | 279 (48) | 1579 (60) | |

| Non-diploid and high stroma | 89 (8) | 62 (6) | 140 (24) | 291 (11) | |

| Microsatellite instability status | 0.037 | ||||

| Microsatellite stable | 896 (88) | NA | 452 (84) | 1348 (86) | |

| Microsatellite instable | 126 (12) | NA | 87 (16) | 213 (14) | |

| Adjuvant treatment | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 0 | 567 (89) | 434 (90) | 1001 (45) | |

| Yes | 1092 (100) | 72 (11) | 49 (10) | 1213 (55) | |

| Total number | 1092 | 954 | 578 | 2624 |

P-value for the comparison of variable between datasets.

One-way analysis of variance.

SD, standard deviation; NA, not available; OUH-Aker, Oslo University Hospital—Aker.

Univariate prognostic factors for CSS

Univariate analyses of the individual datasets are summarised in supplementary Tables S1A–C, available at Annals of Oncology online.

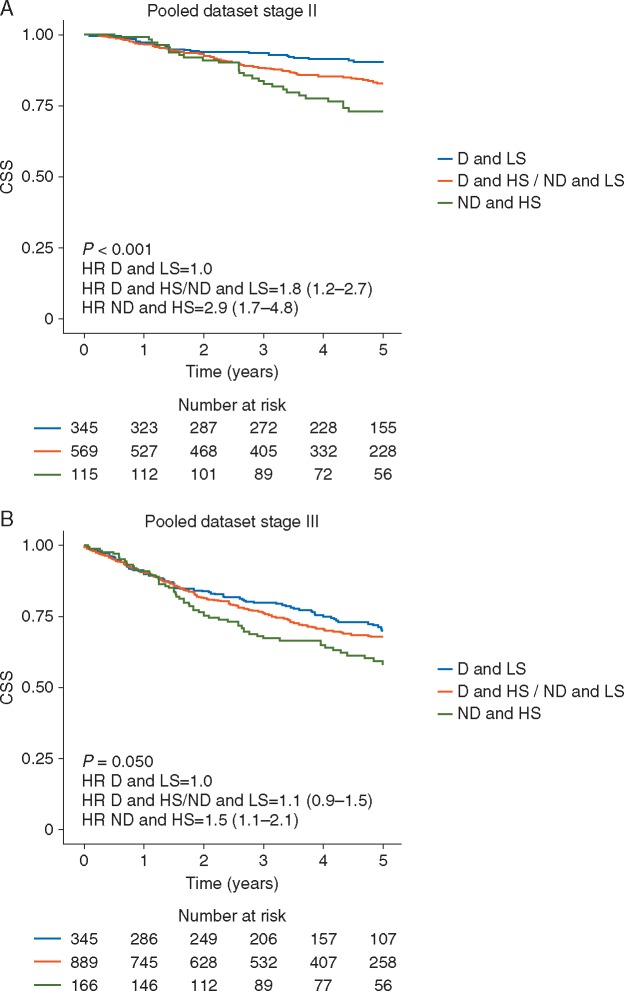

In the pooled dataset, the combination of ploidy and stroma was statistically significant in stage II tumours (P < 0.001, supplementary Table S1D, available at Annals of Oncology online). Diploid and low stroma tumours represented a patient group with low cancer-specific mortality [5-year CSS 90% (95% confidence interval (95% CI): 87% to 94%)], while diploid and high stroma tumours together with non-diploid and low stroma tumours constituted an intermediate group with increased cancer-specific mortality compared with the low-risk group [5-year CSS 83% (95% CI: 79% to 86%), hazard ratio (HR) 1.79 (95% CI: 1.17–2.73)]. Non-diploid and high stroma tumours characterised a group of patients with high risk for cancer-specific mortality [5-year CSS 73% (95% CI: 65% to 82%), HR 2.87 (95% CI: 1.71–4.82), Figure 1A]. Five-year OS for the low, intermediate and high risk groups among stage II patients were 79%, 72% and 63%, respectively. Similarly, in QUASAR 2, 3-year DFS rates were 92%, 85% and 72%, while the corresponding figures in the Aker dataset were 82%, 72% and 59%, respectively. In the Gloucester dataset, DFS was not available.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier plots illustrating cancer-specific survival (CSS) for patients with tumours that were diploid and low stroma (D and LS), diploid and high stroma or non-diploid and low stroma (D and HS/ND and LS), and non-diploid and high stroma (ND and HS) among (A) patients with stage II tumours and (B) patients with stage III tumours.

The combined ploidy-stroma marker had a less marked prognostic impact among stage III tumours (P = 0.050), with 5-year CSS of 70% (95% CI: 64% to 76%) in the low-risk group, 68% (95% CI: 64% to 71%) with HR 1.13 (95% CI: 0.88–1.45) in the intermediate risk group, and 58% (95% CI: 50% to 67%) with HR 1.50 (95% CI: 1.08–2.09) in the high-risk group (Figure 1B). Five-year OS for the low, intermediate and high risk groups among stage III patients were 61%, 59% and 48%, respectively. Similarly, 3-year DFS rates in QUASAR 2 were 73%, 73% and 53%, while the corresponding figures in the Aker dataset were 67%, 46% and 50%, respectively.

Patients with pT4 tumours had an inferior prognosis compared with pT3 tumours in both stage II and stage III [HR 1.42 (95% CI: 1.01–2.01), P = 0.043 and HR 2.81 (95% CI: 2.28–3.46), P < 0.001, respectively].

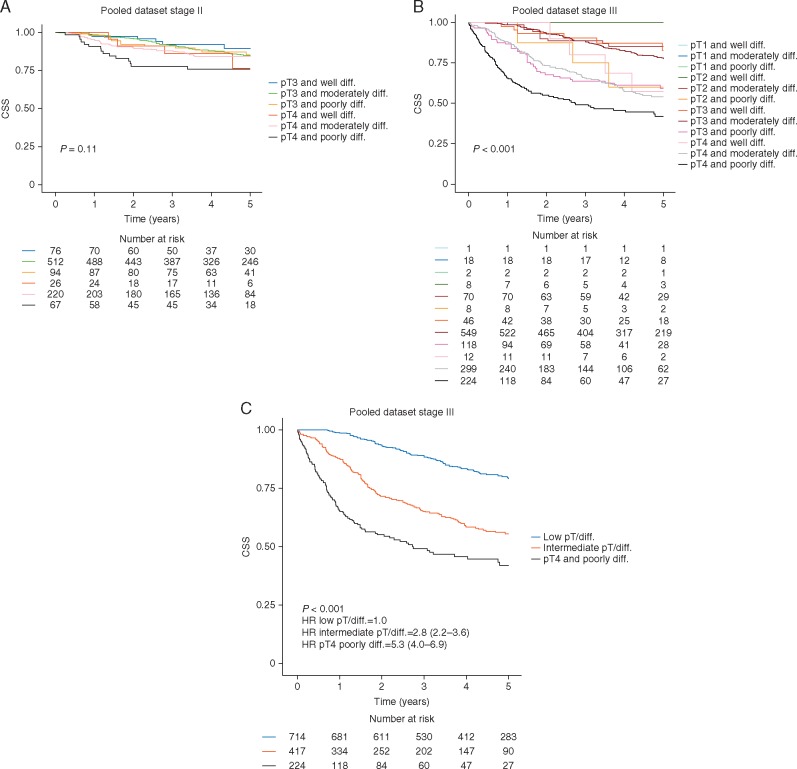

Among stage III tumours, tumour differentiation was a significant prognostic marker [HR 1.65 (95% CI: 0.88–3.11) for moderate versus well differentiated and HR 4.49 (95% CI: 2.37–8.53) for poor versus well differentiated tumours, P < 0.001].

The combination of pathological T-stage and degree of tumour differentiation was not prognostic in stage II disease (Figure 2A), whereas, among stage III patients, poorly differentiated pT4 tumours [224 of 1355 (17%)] have the worst outcome, while poorly differentiated pT3 and moderately differentiated pT4 [417 of 1355 (31%)] constitute an intermediate risk group (Figure 2A and B).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier plots illustrating cancer-specific survival (CSS) for patients stratified by pathological stage and histological grade in the pooled dataset. (A) Stage II disease. (B) Stage III disease. (C) Stage III disease—aggregated version grouped as pT1 or pT2 (Low pT/diff.), pT3 or well- or moderately differentiated pT4 tumours (Intermediate pT/diff.), and pT4 and poorly differentiated tumours (pT4 and poorly diff.).

MSI did not have a significant impact in univariate analyses [MSI versus MSS HR = 0.73 (95% CI: 0.40–1.35), P = 0.32) in stage II, and HR = 1.19 (95% CI: 0.75–1.87, P = 0.46) in stage III disease].

QUASAR 2 patients receiving bevacizumab did not have a significantly different prognosis than those that received capecitabine alone when stratifying for stroma content and stage, indicating that patients with a high stroma content do not benefit from VEGF inhibition (supplementary Tables S4A and B, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Multivariate analyses of prognostic factors for CSS

Multivariate analyses of the individual datasets are summarised in supplementary Tables S2A–F, S3A-D and S5A-C, available at Annals of Oncology online.

The pooled dataset comprising QUASAR 2, Gloucester and Aker populations are summarised in Tables 2 and 3. In multivariate modelling, the dominant contributory factors for stage II disease were the combination of ploidy and stroma [P < 0.001, HR 1.77 (95% CI: 1.13–2.77)] for the intermediate- versus low-risk group and HR 2.95 (95% CI: 1.73–5.03) for the high- versus low-risk group), pathological stage T4 versus T3 [HR 1.99 (95% CI: 1.35–2.93), P < 0.001], utilisation of adjuvant chemotherapy [HR 0.44 (95% CI: 0.29–0.69), P < 0.001] and age [HR 1.02 (95% CI: 1.00–1.04), P = 0.011]. It was considered reasonable to pool these datasets as we prepared a multivariate model in which adjuvant chemotherapy (yes/no) was included as a covariate in this analysis. This showed that adjuvant chemotherapy does not change the HRs for ploidy/stroma. Without adjuvant treatment as covariate: HR 1.77 (95% CI: 1.15–2.70) for the intermediate-risk group and HR 2.83 (95% CI: 1.68–4.76) for the high-risk group.

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis on 5-year cancer-specific survival of the prognostic factors in stage II patients in the pooled dataset

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Ploidy and stroma | <0.001 | |

| Diploid and low stroma | 1 | |

| Diploid and high stroma/non-diploid and low stroma | 1.77 (1.13–2.77) | |

| Non-diploid and high stroma | 2.95 (1.73–5.03) | |

| pT stage | 0.001 | |

| pT3 | 1 | |

| pT4 | 1.99 (1.35–2.93) | |

| Adjuvant treatment | <0.001 | |

| No | 1 | |

| Yes | 0.44 (0.29–0.69) | |

| Age | 1.02 (1.01–1.04) | 0.011 |

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis on 5-year cancer-specific survival of the prognostic factors in stage III patients in the pooled dataset

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Ploidy and stroma | 0.14 | |

| Diploid and low stroma | 1 | |

| Diploid and high stroma/non-diploid and low stroma | 1.21 (0.92–1.60) | |

| Non-diploid and high stroma | 1.43 (1.00–2.06) | |

| pT stage | <0.001 | |

| pT1 | NA | |

| pT2 | 1 | |

| pT3 | 0.89 (0.50–1.59) | |

| pT4 | 1.84 (1.03–3.29) | |

| pN stage | <0.001 | |

| pN1 | 1 | |

| pN2 | 2.62 (2.07–3.30) | |

| Histological grade | 0.010 | |

| Well differentiated | 1 | |

| Moderately differentiated | 1.36 (0.67–2.76) | |

| Poorly differentiated | 1.96 (0.95–4.07) | |

| Adjuvant treatment | <0.001 | |

| No | 1 | |

| Yes | 0.37 (0.29–0.47) | |

| Age | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) | 0.13 |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; NA, not available.

In stage III, significant factors included histological grade [HR 1.36 (95% CI: 0.67–2.76) for moderately versus well differentiated tumours and HR 1.96 (95% CI: 0.95–4.07) for poorly versus well differentiated tumours, P = 0.010], pathological T-stage [HR 0.89 (95% CI: 0.50–1.59) for pT3 versus pT2 tumours and HR 1.84 (95% CI: 1.03–3.29) for pT4 versus pT2, P < 0.001] and adjuvant treatment [HR = 0.37 (95% CI: 0.29–0.47), P < 0.001, Table 3].

Relapse-free survival was available for the QUASAR 2 and Aker populations and these data are shown in supplementary Tables S3A–D, available at Annals of Oncology online. Interestingly, there is a stronger multivariate association between ploidy/stroma for stage II patients using this end point.

Discussion

Like most epithelial tumours, CRCs are composed of two interdependent cellular compartments: malignant epithelium and tumour stroma. Tumour stroma (consisting of extracellular matrix admixed with fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, endothelial cells and inflammatory and immune infiltrative cells) is considered to make a critical contribution to tumour biology in terms of survival, growth, invasion and metastatic potential.

Recently, tumour-stromal measurement utilising visual estimation has been applied to tissue sections from 710 patients enrolled in the VICTOR trial, suggesting that tumours comprising more than 50% stroma have significantly poorer prognosis [12]. The explanation for the effect described here is currently unknown, but there are data to suggest that there may be enhanced pro-invasive signalling by intra-stromal myofibroblasts or growth factor/cytokine production by cancer-associated fibroblasts inducing enhanced angiogenesis, increased tumour growth and invasion, possibly through induction of a mesenchymal stem cell phenotype. Guinney et al. [22] used gene expression profiles to define several subtypes of colorectal cancer, one of which, CMS4, showed significant upregulation of genes implicated in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and of signatures compatible with stromal infiltration. More recently Isella et al. [23] have shown that the distinctive transcriptional and clinical features of this subtype can be ascribed to its particularly abundant stromal component, consistent with findings in the current study. Angell and Galon [16] have explored the prognostic impact of immune infiltrates. Using digital quantification of CD3 and CD8 lymphocytes following immunohistochemical staining, they suggest that a low immune infiltrate score is associated with a higher relapse rate. Recently, Mlecnik et al. demonstrated the presence of functional mutation-specific cytotoxic T cells and the superiority of immunoscore over MSI in predicting survival, as is the case with the ploidy/stroma assay [24].

The association between ploidy and poor prognosis is well documented (reviewed in [25]). Current opinion is that damage to the cellular apparatus of mitosis within epithelial tumours at an early stage can produce cells with chromosomal instability and that these genetically unstable cells drive tumorigenesis by producing progeny with diverse (uncharacterised) genetic alterations conferring survival advantages.

Individually, mutations in TP53, PIK3CA and KRAS are very weak prognostic markers. BRAF, which is prognostic in advanced CRC, is much less so for the primary tumour [8]. Most of these studies have suffered from small sample size, poorly curated tissue banks, inadequate validation on independent datasets and a lack of assay quality control. Morphometric analyses of ploidy and stroma (Figure 1A) has provided a technically simple prognostic stratifier for stage II CRC which is likely to be clinically useful. By defining a substantial proportion (34%) of patients with good prognosis (90% 5-year CSS), it will inform discussion with the patient as to the absolute benefits of adjuvant chemotherapy. The HR, separating relatively good from relatively poor prognosis [HR 2.95 (95% CI: 1.73–5.03, P < 0.001] for the ploidy-stromal classifier is superior to the HR generated for stage II colon cancer patients by the RNA signature [11] Oncotype Dx ColonTM (HR = 1.47, P = 0.046), although no direct comparison of the two tests has been made. For patients with high stroma that undergo adjuvant therapy, reports indicate that this group of patients have shorter survival and thus that further substratification is required [15]. Although digital pathology is widely available, the ploidy element of the assay needs to be established in accredited central laboratories, which offer the most practical, initial means of delivering the assay.

This combined biomarker was not prognostic for stage III CRC, where the clinical default is to offer patients combination adjuvant chemotherapy with a fluoropyrimidine and oxaliplatin. As shown in Figure 2C, it might be possible to challenge this paradigm and consider single agent chemotherapy for the low-risk group, particularly in elderly patients.

Although there is significant international variation in clinical practice, in the UK, around 50% of stage II colon cancer patients receive adjuvant chemotherapy, a proportion of which is administered in combination, overtreating the general population of patients so that a small minority might benefit. The use of this new prognostic biomarker will identify approximately 34% of stage II patients with a prognosis similar to stage I patients who might therefore avoid adjuvant treatment, 55% of intermediate prognosis who might benefit from adjuvant fluoropyrimidine monotherapy and 11% with a bad prognosis of whom the patient and clinician might consider that combination therapy with oxaliplatin would be merited, in patients under 70 years of age.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Wanja Kildal, Marna Lill Kjæreng and the laboratory personnel at the Institute for Cancer Genetics and Informatics for technical assistance, the reviewers and editors of Annals of Oncology for valuable comments, and last, but not least, the participating patients.

Funding

The QUASAR 2 study was funded by an educational grant from Roche (no grant number applies).

Disclosure

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. La Thangue NB, Kerr DJ.. Predictive biomarkers: a paradigm shift towards personalized cancer medicine. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2011; 8(10): 587–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Church D, Kerr R, Domingo E. et al. ‘Toxgnostics’: an unmet need in cancer medicine. Nat Rev Cancer 2014; 14(6): 440–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Quasar Collaborative Group, Gray R, Barnwell J. et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy versus observation in patients with colorectal cancer: a randomised study. Lancet 2007; 370: 2020–2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. de Gramont A, Van Cutsem E, Schmoll HJ. et al. Bevacizumab plus oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer (AVANT): a phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2012; 13(12): 1225–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Andre T, Boni C, Navarro M. et al. Improved overall survival with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment in stage II or III colon cancer in the MOSAIC trial. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27(19): 3109–3116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schmoll HJ, Tabernero J, Maroun J. et al. Capecitabine plus oxaliplatin compared with fluorouracil/folinic acid as adjuvant therapy for stage III colon cancer: final results of the NO16968 randomized controlled phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 3733–3740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yothers G, O'Connell MJ, Allegra CJ. et al. Oxaliplatin as adjuvant therapy for colon cancer: updated results of NSABP C-07 trial, including survival and subset analyses. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 3768–3774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hutchins G, Southward K, Handley K. et al. Value of mismatch repair, KRAS, and BRAF mutations in predicting recurrence and benefits from chemotherapy in colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 1261–1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kerr DJ, Midgley R.. Defective mismatch repair in colon cancer: a prognostic or predictive biomarker? J Clin Oncol 2010; 28(20): 3210–3212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ribic CM, Sargent DJ, Moore MJ. et al. Tumor microsatellite-instability status as a predictor of benefit from fluorouracil-based adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med 2003; 349(3): 247–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gray RG, Quirke P, Handley K. et al. Validation study of a quantitative multigene reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction assay for assessment of recurrence risk in patients with stage II colon cancer. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 4611–4619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huijbers A, Tollenaar RA, v Pelt GW. et al. The proportion of tumor-stroma as a strong prognosticator for stage II and III colon cancer patients: validation in the VICTOR trial. Ann Oncol 2013; 24(1): 179–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. West NP, Dattani M, McShane P. et al. The proportion of tumour cells is an independent predictor for survival in colorectal cancer patients. Br J Cancer 2010; 102(10): 1519–1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mesker WE, Junggeburt JM, Szuhai K. et al. The carcinoma-stromal ratio of colon carcinoma is an independent factor for survival compared to lymph node status and tumor stage. Cell Oncol 2007; 29: 387–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Park JH, Richards CH, McMillan DC. et al. The relationship between tumour stroma percentage, the tumour microenvironment and survival in patients with primary operable colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol 2014; 25(3): 644–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Angell H, Galon J.. From the immune contexture to the Immunoscore: the role of prognostic and predictive immune markers in cancer. Curr Opin Immunol 2013; 25(2): 261–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shepherd NA, Baxter KJ, Love SB.. The prognostic importance of peritoneal involvement in colonic cancer: a prospective evaluation. Gastroenterology 1997; 112(4): 1096–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mitchard JR, Love SB, Baxter KJ, Shepherd NA.. How important is peritoneal involvement in rectal cancer? A prospective study of 331 cases. Histopathology 2010; 57(5): 671–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Merok MA, Ahlquist T, Royrvik EC. et al. Microsatellite instability has a positive prognostic impact on stage II colorectal cancer after complete resection: results from a large, consecutive Norwegian series. Ann Oncol 2013; 24(5): 1274–1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hveem TS, Merok MA, Pretorius ME. et al. Prognostic impact of genomic instability in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 2014; 110(8): 2159–2164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pradhan M, Abeler VM, Danielsen HE. et al. Prognostic importance of DNA ploidy and DNA index in stage I and II endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the endometrium. Ann Oncol 2012; 23(5): 1178–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Guinney J, Dienstmann R, Wang X. et al. The consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. Nat Med 2015; 21(11): 1350–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Isella C, Terrasi A, Bellomo SE. et al. Stromal contribution to the colorectal cancer transcriptome. Nat Genet 2015; 47(4): 312–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mlecnik B, Bindea G, Angell HK. et al. Integrative analyses of colorectal cancer show immunoscore is a stronger predictor of patient survival than microsatellite instability. Immunity 2016; 44(3): 698–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Danielsen HE, Pradhan M, Novelli M.. Revisiting tumour aneuploidy – the place of ploidy assessment in the molecular era. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2016; 13(5): 291–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.