The impressive progress recently observed in adult cancers through the introduction of new drugs has not yet been translated to adolescents 12–17 years of age [defined according to the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) E11]. The current drug development landscape separates adult and paediatric drug development (Table 1). Adolescents are grouped with children, leading to a mismatch with a lack of trials for adolescents with relapsed cancer and delayed access to new, effective drugs already available for adults.

Table 1.

European regulation and current drug development landscape for adolescents

| European regulation |

|

| Consequences on current drug development landscape for adolescents |

|

The European Paediatric Medicine Regulation [(EC)-No1901/2006)] has dramatically improved the European regulatory environment for the development of paediatric medicines in the EU and has had an international impact [27].

In some cancer types with identical drug targets in the paediatric and adult populations, adult phase II trials have demonstrated efficacy, but paediatric clinical development commenced much later. This has resulted in significantly delayed introduction of beneficial drugs to adolescents (e.g. brentuximab vedotin in Hodgkin’s disease; Table 2). In diseases too rare in adolescents to allow completion of paediatric trials within a reasonable timeframe, even with worldwide accrual over several years, a very low (but not non-existent) incidence of a condition in adolescents has triggered the regulatory requirement for an adolescent study, while waivers have been granted, based on the absence of the condition, for studies in children < 12 years. This has resulted in ‘unfeasible’ adolescent-specific phase I trials, using a drug already demonstrated effective in adults with the same disease (e.g. vemurafenib development in melanoma; Table 2). Both situations have inadvertently lead to off label drug use in adolescents, with no data collected, delaying adolescent data collection for marketing authorisation.

Table 2.

Implication of the current situation for adolescents with cancer—concrete examples

| Delay of drug access in common diseases |

| Hodgkin’s lymphoma occurs in children, adolescents and adults, with very similar biology and clinical behaviour. Brentuximab vedotin was approved for adult with relapsed/refractory CD30 positive Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NCT00430846) [28] in October 2012 in Europe, while the phase I/II trial for patients aged < 18 years, which was included in a PIP, only started in April 2012 (NCT01492088) thus delaying authorisation of this promising drug for adolescent use. Moreover, since March 2015, the drug is being evaluated in combination in a first line study (NCT02292979) in adult Hodgkin’s lymphoma, but adolescents are excluded from this trial. The same pattern also occurred with the anti-PD1 immune checkpoint inhibitor (nivolumab) trials in adult Hodgkin’s lymphoma [29] (NCT01592370 and NCT02304458), although delays were reduced. |

| ‘Unfeasible’ adolescent-specific trials |

| A phase I trial of vemurafenib was opened internationally in January 2013 only for 12- to 17-year olds with stage IIIC and IV melanoma and B-RAF V600 mutations (NCT01519323), despite this disease being extremely rare in adolescents [30], while an adult study started recruitment from 16 years old upwards in March 2011 (NCT01307397). Confounding the situation was off label use of this drug in adolescents with no data formally collected. Only 6 patients were recruited to NCT01519323 despite it being open in 10 countries. Recently, adult studies have proven that the combination of vemurafenib with an MEK inhibitor provides a better therapeutic option than single agent vemurafenib [31]. Similarly, the adolescent melanoma phase I/II ipilimumab trial was closed prematurely because of low accrual (NCT01696045), at a time when the melanoma standard-of-care had changed with the emergence of the anti-PD1 antibodies, and the PIP covering the paediatric melanoma development required recruitment of adolescents into ongoing adult trials. |

The multi-stakeholder platform ACCELERATE (http://www.accelerate-platform.eu) [1] presents a consensus expert opinion, based on a literature review and multidisciplinary discussions between representatives from academia, patient/parent advocacy groups, regulatory agencies and pharmaceutical companies, which aims to improve early drug access for adolescents with cancer.

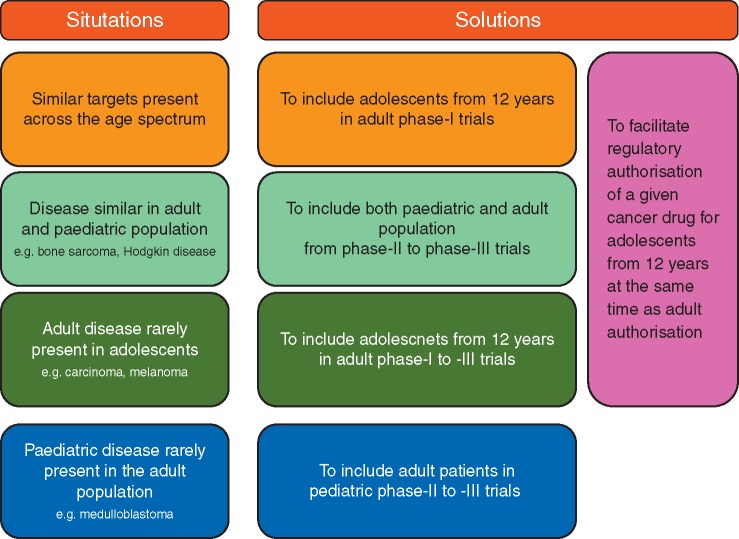

We propose a rational approach to drug development based on the mechanism of action (MoA) of the drug, the therapeutic need and disease epidemiology in adolescents; and similarity between adolescents and adults disease, physiology and drug exposure. Enrolment of adolescents of 12 years and over in adult early-phase clinical drug trials, even in phase I first-in-human trials, may represent a safe and more efficient alternative compared with the current unsatisfactory situation (Figure 1). This approach is complementary to existing paediatric and adult drug development approaches and should not replace, or delay them; rather it increases opportunities for adolescents to be included in early-phase trials [2].

Figure 1.

ACCELERATE trial strategy for adolescents and young adults.

Despite the theoretical concern that the inclusion of adolescents within adult early-phase studies could risk a drug’s adult development should there be unacceptable toxicity in a minor, the evidence to date demonstrates that the proposed approach is safe (no extra acute toxicity issues), does not infringe legal or regulatory boundaries and would not detrimentally affect the conclusions of the adult trials [similar phase II recommended dose (RP2D) and pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters]. There is neither a difference in safety monitoring between adults and adolescents nor in regulatory obligations (e.g. ICH-E6 [3]) and oversight of authorised clinical trials. Late effects are rarely observed in early trials due to the low overall survival rates and are better identified during late or post-authorisation phase trials. To date, we are not aware of any adverse events observed in adolescents or children have hindered the registration process in adults.

The influence of pubertal endocrine changes (changes in body composition, maturation of liver metabolism and renal function) [4] on drug metabolism does not generally result in additional safety risks. Animal models used in pre-clinical drug development have an equivalent human age ranging from around 12 years old to mature adults, facilitating pre-clinical study of potential safety issues. Comparisons of adult and paediatric phase I trials of chemotherapeutic [5], molecularly targeted [6] and immunotherapeutic agents (monoclonal antibodies [7, 8], immune checkpoint Inhibitors [9]) revealed no specific safety concerns for adolescents ≥ 12 years. Acute toxicity profiles were similar in both paediatric and adult populations with a lower rate of dose limiting toxicity in children compared with adults (0.5% versus 2–3%) [5, 6, 10]. The maximal tolerated dose (MTD) determined in adult and paediatric phase I trials were within the same range, whatever the class of anticancer agent used. The correlation between paediatric MTD (pMTD) and adult MTD (aMTD) was strong for chemotherapeutic agents (r = 0.97; pMTDs = 80–160% of aMTDs in 80% of phase I trials) [5], molecularly targeted agents [pMTD = 90–100% of the body surface area (BSA)-adjusted aMTD, pRP2D = 90–130% of the BSA-adjusted approved adult dose for 70% of trials and 75% of compounds evaluated) [6], and immunotherapies (pRP2D = 100–120% of the BSA-adjusted approved dose in adults) [6–9]. A rare exception was sunitinib, with a pRP2D lower than in adults and different main toxicities. However, case reports have recorded children tolerating higher doses, and a large percentage of adults on sunitinib have to undergo dose reductions with cumulative dosing [11].

PK parameters are similar between adolescent and adult populations [5, 12]. For cytotoxic agents, paediatric and adult plasma drug clearance were correlated [r = 0.97; median coefficient of variation = 42% (11%–69%), median paediatric/adult ratio = 0.95 (0.06–2.2)] [5]. Adolescent PKs resembled those in adults, although differences were seen between younger children and adolescents ≥ 10–12 years [4]. Oral absorption appeared similar to adults from 5 to 10 years of age onwards [4]. The exception was erlotinib [6], where the mean weighted clearance although lower than in children was not significantly different between adolescents and adults [13].

Despite common misconceptions, there are no legal or regulatory barriers to including adolescents in adult phase I/II trials and to including young adults in paediatric trials. Although the FDA regulations and EU pharmaceutical legislation are not identical, no obstacles exist to the inclusion of minor patients within adult trials in the US either [14], thus facilitating international transatlantic trial conduct in both populations.

Changes are needed to ensure adolescents access early drug development programmes

Changes are proposed to improve access of new anticancer drug to adolescents and efficiency of drug development (Figure 1).

In adult early-phase anticancer drug studies, the age of entry into clinical trials should be lowered to 12 years where the agent has an MoA relevant to adolescents’ unmet treatment needs, especially when the disease is rarely present in adolescents (making separate studies unlikely), unless there are well-justifiable medical and/or scientific reasons not to do so.

There should be no set upper or lower age limit criteria for phases II and III trials for adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancers that are present in both paediatric and adult populations with similar biology. Adolescents over 12 years of age should be included from the onset of the cancer drug development process in adults. Additional adolescent PK and toxicity studies should be undertaken in phase II studies. Children < 12 years should be studied as soon as the pRP2D is determined.

Trials enrolling adolescents should always be conducted in an age-appropriate setting with clinical care provided by expert paediatric or AYA oncologists, to ensure best safety, care and compliance. This could be facilitated by having co-principal investigators, with separate responsibilities for adults and adolescents.

Adolescents should be included in paediatric phase I, II and III trials where relevant (e.g. adolescents with paediatric cancers type or biological targets).

Young adult with paediatric cancer types should be offered to participate in paediatric phase II/III trials.

This approach should yield adequate data to support an adolescent indication at the time of the initial marketing authorisation application for a given anticancer drug, particularly where the disease crosses the age spectrum and has similar biological and clinical behaviour, or when diseases are histologically different but have similar targets present across the age spectrum. Adolescent PK/safety data collected in adult trials, even within trials for different diseases, might support extrapolation of activity between diseases if the targets are the same.

Key success factors for the implementation of a joint adolescent–adult clinical trial platform

Firstly, the early opening of adolescent slots in adult trials, i.e. before the adult recruitment is well advanced (e.g. denosumab in giant cell tumours, NCT00680992) [15] is crucial. The timing should be balanced between opening to adolescents once there is some adult safety and PK data, but not so late that few can realistically participate. This time point could be defined on a study-by-study basis (e.g. once safety data from the first 1–2 adult cohorts have been assessed; or at the point of adult expansion cohorts opening). This will avoid that adolescents being exposed to potentially sub-therapeutic doses, and maximise the chance for individual benefit, complying with the requirement that paediatric/adolescent patients participating in research have the prospect of direct benefit which justifies the risk of participation.

Drug dosage may be calculated as BSA-adjusted adult dose without exceeding that adult dose. For this, appropriate tablet/pill strengths should be made available for optimal dosing without necessarily requiring liquid formulation. Dosing in adolescents can also be modelled based on population PK modelling of the dose-finding data obtained from adults. Drug concentrations in adolescents can be determined during the trial and PK can be confirmed in late-phase adult trials.

The number of adolescents to be recruited should be included within the upfront overall enrolment calculation, and the pre-specified primary analyses designed to include the adolescent data. We propose not to pre-define a minimum number of adolescents to be recruited, in order to avoid delays in completion, reporting and publication of the trial and authorisation process. However, it is crucial that this upfront agreement is not merely a token gesture. Involvement of experts in both adult and paediatric oncology early drug development will help design the most appropriate studies to ensure that adolescent inclusion does not delay the study execution. This process could be eased by having adult and paediatric oncology co-principal investigators and at least one paediatric/AYA oncology expert on the Trial Steering Committee. Several academic institutions host both adult and paediatric early drug development departments, thereby facilitating the capture of adolescent patients into trials. The structure of paediatric early drug development in Europe through the consortia such as ITCC will facilitate referral of adolescents to open sites. Data from adolescents enrolled in adult studies should contribute to data on a given drug for the overall paediatric population. Joint paediatric/adult trials can be considered in PIP proposals.

Adolescents require a dedicated environment in specialised centres and age-appropriate assent and consent forms. Consideration should be given to local and national regulations regarding enrolment of minors in clinical trials, including acceptability of contraception. Harmonisation of trial authorisation process for minors by competent authorities, institutional review boards and ethics committees is warranted, and will require further work in this area.

Adolescents and their parents are leading co-drivers of this initiative and strongly support a joint adolescent/adult approach. Early and rapid access to new drugs is a priority for all patients experiencing a cancer relapse, and their wish is to be proactively informed about available trials. Adolescents define themselves as the ones who have to live with the disease without current chance of cure and thus claim to understand and freely choose whether or not to participate in a trial once they have had clear explanations of expected adverse effects and uncertainties about drug efficacy. They are more than willing to participate in adult trials to increase the chance of their own disease responding, as well as for altruistic reasons, as long as they can still be treated in an age-appropriate environment. These factors are crucial for trial compliance, and data quality.

A consensus exists and progress is ongoing

There are many benefits of including adolescents in adult phase I/II trials once safety and PK data are available from adult patients but without the need for prior paediatric data. Firstly, it accelerates access to new drugs for adolescents and potentially provides data to inform drug development in both children and adults, e.g. figitumumab in Ewing’s sarcoma [16]; crizotinib in ALK/MET aberrant tumours, NCT01524926. Where early signs of activity are seen in a paediatric disease present in adolescents, the opportunity exists for adolescent data to inform broader paediatric drug development. The development of drugs in adults might also be positively influenced by recruiting adolescents whose tumours harbour an oncogenic driver or drug target which might achieve proof-of-concept/proof-of-principle for drugs with a new MoA. This approach should ultimately shorten the paediatric drug development and reduce the likelihood of off-label use in the paediatric population once the drug is authorised for adult use. An additional benefit is to advance the understanding of the biology related to new drugs (e.g. vismodegib in SHh-medulloblastoma [17–19] where medulloblastoma molecular biology was investigated across ages to an unprecedented level [20]). Importantly, this approach has already strengthened links between paediatric and medical oncologists, building on experience gained in successful joint paediatric-adult phase III trials [21], and support initiatives such as the French InterSARC network (joint phase II/III trials in adult and paediatric sarcomas). Similarly collaboration between tumour profiling programmes at relapse, with analyses performed for the adult and paediatric populations (e.g. MOlecular Screening for Cancer Treatment Optimization [22] may identify new druggable alterations relevant for future MoA-based treatment strategies). Joint AYA initiatives led by the academic community are now moving forward under the auspices of the European Society for Paediatric Oncology (SIOPE) and of Medical Oncology, as a result of the work done by the different national AYA groups, in particular within the ENCCA [23]. The fifth SIOPE cancer strategy plan includes adolescent access to new drugs as a priority. Finally, from an operational and cost stand points, this approach alleviates the burden of opening an adolescent-specific trial in cancers with a low incidence in adolescents (e.g. melanomas, gastrointestinal stromal tumours, thyroid cancers, carcinomas) and permit an integrated adult/paediatric data set for regulatory decision making. This is in line with the ICH-E11 guidance (2016), which stipulates that paediatric data should be included at an early stage in adult marketing authorisation applications for medicinal products that may represent a significant therapeutic advance in diseases with limited therapeutic options.

Conclusion

ACCELERATE proposes adult phase I/II trials to include adolescents above the age of 12 years, which is not only ethical, but feasible and safe, unless there are medical or scientific contraindications, either where the MoA of the drug being studied is potentially relevant to adolescents or when the disease is rarely present in the adolescent population. This approach is supported by similar dosing and PK parameters in adolescents and adults and no extra toxicity observed in adolescents. Very importantly, inclusion of adolescent in clinical trials in adults should neither delay the activation, completion, nor reporting and publication of the trial and authorisation process. Finally, our proposed strategy has very recently been endorsed by the FDA, further demonstrating the progressive international harmonisation of views on this key issue [24].

Acknowledgements

To all the AYA patients, the parents and the health care professionals who participate to this reflection and could not all be included as authors.

Funding

This publication has received funding from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme for research, technological development and demonstration under the project ENCCA (European Network for Cancer research in Children and Adolescents) (HEALTH-F2-2011-2614). LVM is funded by the Oak Foundation (OCay-04-169). JS was supported by project no. LO1605, 1413 from the National Program of Sustainability II (MEYS CR) and by project FNUSA-ICRC no. CZ.1.05/1.1.00/02.0123 (OP VaVpI) and Czech Republic Ministry of Health grant 16-33209A and 16-34083A. JYB: supports for NetSARC/RREPS/InterSARC (INCA), LYRIC (INCA-DGOS 4664), EuroSARC (FP7 278742).

Disclosure

Several authors are employees of pharma industries or of the European Medicines Agency (EMA). JCS has left Institut Gustave Roussy and is now an employee of MedImmune, Inc. (Gaithersburg, MD, USA). All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the personal views of the authors and may not be understood or quoted as being made on behalf of or reflecting the position of their respective institutions, employing companies, European Medicines Agency or one of its committees or working parties.

References

- 1. Vassal G, Rousseau R, Blanc P. et al. Creating a unique, multi-stakeholder Paediatric Oncology Platform to improve drug development for children and adolescents with cancer. Eur J Cancer 2015; 51(2): 218–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pearson ADJ, Herold R, Rousseau R. et al. Implementation of mechanism of action biology-driven early drug development for children with cancer. Eur J Cancer 2016; 62: 124–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. ICH harmonized tripartite guideline: Guideline for Good Clinical Practice. J Postgrad Med 2001; 47(1): 45–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Veal GJ, Hartford CM, Stewart CF.. Clinical pharmacology in the adolescent oncology patient. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28(32): 4790–4799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lee DP, Skolnik JM, Adamson PC.. Pediatric phase I trials in oncology: an analysis of study conduct efficiency. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23(33): 8431–8441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Paoletti X, Geoerger B, Doz F. et al. A comparative analysis of paediatric dose-finding trials of molecularly targeted agent with adults’ trials. Eur J Cancer 2013; 49(10): 2392–2402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Meinhardt A, Burkhardt B, Zimmermann M. et al. Phase II window study on rituximab in newly diagnosed pediatric mature B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and Burkitt leukemia. JCO 2010; 28(19): 3115–3121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hoffman LM, Gore L.. Blinatumomab, a bi-specific anti-CD19/CD3 BiTE® antibody for the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia: perspectives and current pediatric applications. Front Oncol 2014; 4:63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Merchant MS, Wright M, Baird K. et al. Phase I clinical trial of ipilimumab in pediatric patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2016; 22(6): 1364–1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Geoerger B, Fox E, Pappo AS. et al. Pembrolizumab in Pediatric Patients with Advanced Melanoma or a PD-L1 Positive Advanced, Relapsed, or Refractory Solid Tumor or Lymphoma: Phase I/II KEYNOTE-051 Study. Dublin: SIOP; 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. DuBois SG, Shusterman S, Ingle AM. et al. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of sunitinib in pediatric patients with refractory solid tumors: a children’s oncology group study. Clin Cancer Res 2011; 17(15): 5113–5122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Momper JD, Mulugeta Y, Green DJ. et al. Adolescent dosing and labeling since the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007. JAMA Pediatr 2013; 167(10): 926.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. White-Koning M, Civade E, Geoerger B. et al. Population analysis of erlotinib in adults and children reveals pharmacokinetic characteristics as the main factor explaining tolerance particularities in children. Clin Cancer Res 2011; 17(14): 4862–4871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Beaver JA, Ison G, Pazdur R.. Reevaluating eligibility criteria—balancing patient protection and participation in oncology trials. N Engl J Med 2017; 376(16): 1504–1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chawla S, Henshaw R, Seeger L. et al. Safety and efficacy of denosumab for adults and skeletally mature adolescents with giant cell tumour of bone: interim analysis of an open-label, parallel-group, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2013; 14(9): 901–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Olmos D, Postel-Vinay S, Molife LR. et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and preliminary activity of the anti-IGF-1R antibody figitumumab (CP-751, 871) in patients with sarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma: a phase 1 expansion cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2010; 11(2): 129–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pappo AS, Vassal G, Crowley JJ. et al. A phase 2 trial of R1507, a monoclonal antibody to the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF-1R), in patients with recurrent or refractory rhabdomyosarcoma, osteosarcoma, synovial sarcoma, and other soft tissue sarcomas: results of a Sarcoma Alliance for Research Through Collaboration study. Cancer 2014; 120(16): 2448–2456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. LoRusso PM, Rudin CM, Reddy JC. et al. Phase I trial of hedgehog pathway inhibitor vismodegib (GDC-0449) in patients with refractory, locally advanced or metastatic solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2011; 17(8): 2502–2511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Robinson GW, Orr BA, Wu G. et al. Vismodegib exerts targeted efficacy against recurrent sonic hedgehog-subgroup medulloblastoma: results from phase II Pediatric Brain Tumor Consortium studies PBTC-025B and PBTC-032. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33(24): 2646–2654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kool M, Jones DTW, Jäger N. et al. Genome sequencing of SHH medulloblastoma predicts genotype-related response to smoothened inhibition. Cancer Cell 2014; 25(3): 393–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fern LA, Lewandowski JA, Coxon KM, Whelan J.. National Cancer Research Institute Teenage and Young Adult Clinical Studies Group, UK. Available, accessible, aware, appropriate, and acceptable: a strategy to improve participation of teenagers and young adults in cancer trials. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15(8): e341–e350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tacher V, Le Deley M-C, Hollebecque A. et al. Factors associated with success of image-guided tumour biopsies: results from a prospective molecular triage study (MOSCATO-01). Eur J Cancer 2016; 59: 79–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stark D, Bielack S, Brugieres L. et al. Teenagers and young adults with cancer in Europe: from national programmes to a European integrated coordinated project. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2016; 25(3): 419–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chuk MK, Mulugeta Y, Roth-Cline M. et al. Enrolling adolescents in disease/target-appropriate adult oncology clinical trials of investigational agents. Clin Cancer Res 2017; 23(1): 9–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. He N. Ethical considerations for clinical trials on medicinal products conducted with the paediatric population. Eur J Health Law 2008; 15: 223–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lepola P, Needham A, Mendum J. et al. Informed Consent for Paediatric Clinical Trials in Europe 2015ropean Network For Paediatric Reearch At the European Medical Agency [on-line]; http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Other/2015/12/WC500199234.pdf (16 January 2018, date last accessed).

- 27.REGULATION (EC) No 1901/2006 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 12 December 2006 on medicinal products for paediatric use and amending Regulation (EEC) No 1768/92, Directive 2001/20/EC, Directive 2001/83/EC and Regulation (EC) No 726/2004. https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/files/eudralex/vol-1/reg_2006_1901/reg_2006_1901_en.pdf (16 January 2018, date last accessed).

- 28. Fanale MA, Forero-Torres A, Rosenblatt JD. et al. A phase I weekly dosing study of brentuximab vedotin in patients with relapsed/refractory CD30-positive hematologic malignancies. Clin Cancer Res 2012; 18(1): 248–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ansell SM, Lesokhin AM, Borrello I. et al. PD-1 blockade with nivolumab in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2015; 372(4): 311–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bleyer A, O’Leary M, Barr R, Ries LAG. Cancer Epidemiology in Older Adolescents and Young Adults 15 to 29 Years of Age, Including SEER Incidence and Survival: 1975-2000. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute (NIH Pub No 06-5767) 2006.

- 31. Spain L, Julve M, Larkin J.. Combination dabrafenib and trametinib in the management of advanced melanoma with BRAFV600 mutations. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2016; 17(7): 1031–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]