Abstract

Background

CYP2C19 loss-of-function (LOF) alleles impair clopidogrel effectiveness after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The feasibility, sustainability and clinical impact of using CYP2C19 genotype-guided dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) selection in practice remains unclear.

Methods and Results

A single-center observational study was conducted in 1193 patients who underwent PCI and received DAPT following implementation of an algorithm that recommends CYP2C19 testing in high-risk patients and alternative DAPT (prasugrel or ticagrelor) in LOF allele carriers. The frequency of genotype testing and alternative DAPT selection were the primary implementation endpoints. Risk of major adverse cardiovascular or cerebrovascular (MACCE) and clinically significant bleeding events over 12 months were compared across genotype and DAPT groups by proportional hazards regression. CYP2C19 genotype was obtained in 868 (72.8%) patients. Alternative DAPT was prescribed in 186 (70.7%) LOF allele carriers. CYP2C19 testing (P<0.001) and alternative DAPT use in LOF allele carriers (P=0.001) varied over time. Risk for MACCE was significantly higher in LOF carriers prescribed clopidogrel versus alternative DAPT (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 4.65, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.22–10.0, P<0.001), whereas no significant difference was observed in those without a LOF allele (adjusted HR 1.37, 95% CI 0.72–2.85, P=0.347). Bleeding event rates were similar across groups (log-rank P=0.816).

Conclusions

Implementing CYP2C19 genotype-guided DAPT is feasible and sustainable in a real-world setting, but challenging to maintain at a consistently high level of fidelity. The higher risk of MACCE associated with clopidogrel use in CYP2C19 LOF allele carriers suggests that use of genotype-guided DAPT in practice may improve clinical outcomes.

Keywords: antiplatelet drug, clopidogrel, cytochrome P450 enzymes, pharmacogenetics cardiovascular disease, implementation

Journal Subject Terms: Genetics, Pharmacology, Acute Coronary Syndromes, Atherosclerosis

INTRODUCTION

Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor is used following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and/or an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) to prevent major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE).1,2 Clopidogrel remains the most commonly prescribed P2Y12 inhibitor at most institutions, although alternative P2Y12 inhibitors (prasugrel and ticagrelor) are widely available.3,4

Clopidogrel is a prodrug that requires biotransformation by cytochromes P450 (CYP) enzymes, most notably CYP2C19, to generate its active metabolite. CYP2C19 loss-of-function (LOF) polymorphisms are common and confer a reduced capacity for clopidogrel bioactivation and platelet inhibition.5 Multiple retrospective analyses have demonstrated a significantly higher risk for MACE after PCI in clopidogrel-treated patients carrying one (intermediate metabolizer, IM) or two (poor metabolizer, PM) CYP2C19 LOF alleles compared to clopidogrel-treated patients without a LOF allele.6–9 In contrast, CYP2C19 genotype does not alter the pharmacokinetics, antiplatelet effects, or clinical response to prasugrel or ticagrelor.8,10 These alternative P2Y12 inhibitors have shown superior efficacy compared to clopidogrel in ACS patients following PCI in clinical trials,11,12 but are more expensive and associated with an increased bleeding risk.2,13,14 It remains unclear whether these effects are due to more potent or more consistent platelet inhibition. A secondary analysis of the TRITON-TIMI 38 study suggested that the overall efficacy benefit conferred by prasugrel over clopidogrel was driven by the increased risk of MACE in CYP2C19 LOF allele carriers randomized to clopidogrel;6,10,15 however, the impact of CYP2C19 LOF alleles on the efficacy benefit of ticagrelor over clopidogrel in the PLATO study was less dramatic.8

Given the lack of prospective clinical outcome data, there remains considerable debate and uncertainty surrounding whether clinical CYP2C19 genetic testing should be routinely used to guide antiplatelet therapy selection in PCI patients.1,5,16–18 Interest in genotype-guided antiplatelet therapy has been enhanced by a series of recent outcome-driven prospective studies, most notably a multi-center pragmatic investigation conducted by the Implementing Genomics in Practice (IGNITE) Network, which have suggested there is clinical benefit associated with using genotype-guided antiplatelet therapy.19–22 Thus, an increasing number of institutions are implementing CYP2C19 genetic testing,23–25 despite limited data on the feasibility, sustainability and clinical impact of using a CYP2C19 genotyping strategy to guide P2Y12 inhibitor selection following PCI in real-world clinical practice. The University of North Carolina (UNC) implemented an algorithm incorporating CYP2C19 genotyping in DAPT selection in 2012;26 therefore, the objectives of this study were to: (1) determine the frequency of CYP2C19 testing and use of alternative therapy in CYP2C19 IMs and PMs over time, (2) identify the factors that influenced CYP2C19 testing and P2Y12 inhibitor selection, and (3) examine the relationship between P2Y12 inhibitor, CYP2C19 status, and clinical outcomes.

METHODS

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Study Design and Population

A clinical algorithm for CYP2C19 genotype-guided selection of antiplatelet therapy following PCI in high-risk patients (defined as ACS or high-risk coronary anatomy) was implemented at the UNC Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory in July 2012 (Supplemental Figure 1), as described.26 The CYP2C19 genotype test is ordered at the interventional cardiologist’s discretion following risk stratification, and performed clinically on-site (Supplemental Methods). Alternative antiplatelet therapy (prasugrel or ticagrelor) is recommended for CYP2C19 IMs and PMs, but the treatment decision is left to the discretion of the prescriber.

This single-center observational cohort study included 1193 consecutive adults ≥18 years of age who underwent PCI with coronary artery stent placement between July 1, 2012 and June 30, 2014 at the UNC Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory, and received DAPT with aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor. The cohort includes 572 patients that underwent CYP2C19 genotyping during the index PCI admission between July 1, 2012 and December 31, 2013, and were included in the Implementing Genomics in Practice (IGNITE) Network multi-center investigation of outcomes.19 The investigation was approved by the UNC Biomedical Institutional Review Board. Since data collection was completed by retrospective review of the electronic health record (EHR), informed consent was not required.

Data Abstraction and Study Endpoints

Data was manually abstracted from the EHR. The primary implementation endpoint was P2Y12 inhibitor maintenance therapy, which was defined as the agent prescribed over the course of follow-up after any changes in therapy. Key secondary endpoints included CYP2C19 genotype availability, initial P2Y12 inhibitor therapy, and changes in therapy.

The primary clinical outcome was the composite of major adverse cardiovascular or cerebrovascular events (MACCE) over 12 months following the index PCI, which was defined as death, myocardial infarction, stent thrombosis, admission for ACS/unstable angina, ischemic cerebrovascular accident (CVA), or transient ischemic attack (TIA). A major secondary outcome was clinically significant bleeding, which was defined as a Global Use of Strategies to Open Occluded Arteries (GUSTO) moderate or severe/life-threatening bleeding event.27 Events were identified using physician-reported diagnoses abstracted from the EHR, and then verified by an interventional cardiologist.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean±standard deviation, median (interquartile range), or count (%) unless otherwise indicated. In order to identify the key demographic and clinical factors associated with CYP2C19 testing and P2Y12 inhibitor selection, associations were evaluated by logistic regression using univariate and multivariable models, and the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each covariate were calculated. Interaction and stratified analyses were also completed. The sustainability of algorithm use over time was assessed by comparing genotype and medication selection endpoints across consecutive 6-month time intervals during the study period (index PCI during July-December 2012, January-June 2013, July-December 2013, or January-June 2014) using chi-square.

The relationship between CYP2C19 status, prescribed P2Y12 inhibitor therapy, and the time to occurrence of the primary (MACCE) and secondary (clinically significant bleeding) clinical outcomes were evaluated using Cox proportional hazards regression in patients with follow-up available after the index PCI admission. Time-to-event analyses were completed after adjusting for covariates that differed across groups or were associated with the clinical outcome, and the adjusted hazard ratio (HR) and 95% CIs for each between-group comparison were calculated. Covariates included in the adjusted model for MACCE included: sex, race, current smoker, history of atrial fibrillation, prior stent, elevated risk of bleeding, ACS indication for PCI; drug eluting stent at index PCI, discharge angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker, discharge beta-blocker, and discharge statin. Covariates included in the adjusted model for bleeding included: sex, race, elevated risk of bleeding, prior stent, ACS indication for PCI, and multiple vessels stented during index PCI. In order to determine whether CYP2C19 genotype modified the association between antiplatelet therapy and MACCE, the interaction between CYP2C19 phenotype (IM/PM or UM/RM/NM) and antiplatelet therapy (clopidogrel or alternative) status was evaluated. Secondary analyses were completed in the strata of patients presenting with an ACS indication for their index PCI. Analyses were performed using SAS-JMP 12.0 and SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Study Population

This single-center observational cohort study included 1193 consecutive adults ≥18 years of age who underwent coronary artery stent placement between 07/01/2012–06/30/2014 and received DAPT. The mean age was 63±12 years, 67.6% were male, 20.7% were African-American, and 53.8% underwent PCI for an ACS indication (Table 1). Upon admission, 26.0% were receiving chronic P2Y12 inhibitor therapy and 40.1% exhibited a risk factor for bleeding.

Table 1.

Study population characteristics.

| Characteristic | N=1193 |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 63.3±12.0 |

| Age ≥ 75 years | 220 (18.4%) |

| Sex (male) | 807 (67.6%) |

| Race | |

| African-American | 247 (20.7%) |

| Asian-American | 7 (0.6%) |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 29.9±6.4 |

| Obese (≥30.0 kg/m2) | 505 (42.3%) |

| Weight <60 kg | 81 (6.8%) |

| Current smoker | 334 (28.0%) |

| Hypertension | 997 (83.6%) |

| Diabetes | 496 (41.6%) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 147 (12.3%) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 109 (9.1%) |

| Heart failure | 191 (16.0%) |

| End-stage renal disease | 47 (3.9%) |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 325 (27.2%) |

| Previous TIA or stroke | 102 (8.5%) |

| Previous significant bleeding event | 112 (9.4%) |

| Elevated bleeding risk * | 478 (40.1%) |

| Previous coronary artery stent | 466 (39.1%) |

| P2Y12 inhibitor use on admission | 310 (26.0%) |

| Clopidogrel | 266 (22.3%) |

| Prasugrel | 43 (3.6%) |

| Ticagrelor | 1 (0.1%) |

| Indication for PCI | |

| Stable angina | 551 (46.2%) |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 642 (53.8%) |

| Unstable angina | 204 (17.1%) |

| NSTEMI | 297 (24.9%) |

| STEMI | 141 (11.8%) |

| Stent placement by vessel at index PCI | |

| Left main | 30 (2.5%) |

| Left anterior descending | 497 (41.7%) |

| Circumflex | 249 (20.9%) |

| Right coronary artery | 359 (30.1%) |

| Bypass graft | 27 (2.3%) |

| Multiple vessels stented | 152 (12.7%) |

| Drug-eluting stent | 1004 (84.2%) |

| Medication use at discharge | |

| Aspirin | 1173 (98.3%) |

| Anticoagulant | 79 (6.6%) |

| ACE inhibitor or ARB | 801 (67.1%) |

| Beta-blocker | 1009 (84.6%) |

| Statin | 1123 (94.1%) |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 371 (31.1%) |

Elevated bleeding risk is a composite variable defined as one or more of the following: age ≥75 years; weight <60 kg; previous TIA or stroke event; previous significant bleeding event; current end stage renal disease requiring dialysis; or, anticoagulant prescribed at discharge.

Genotype Testing

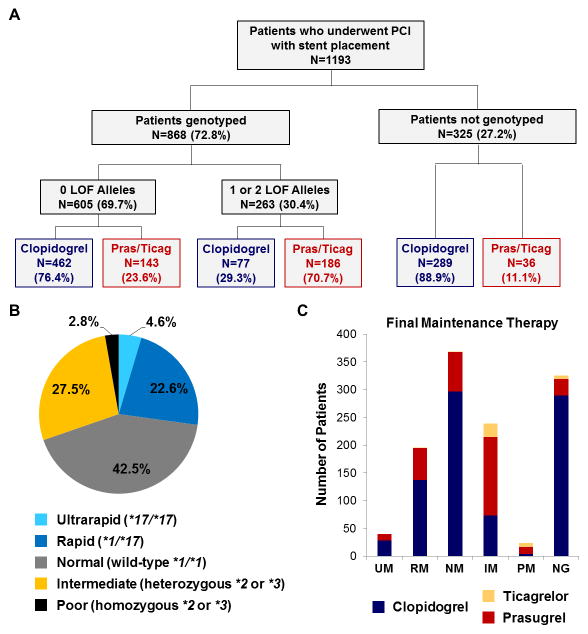

A CYP2C19 genotype was obtained in 868 (72.8%) patients (Figure 1A); of these, 794 (91.5%) were genotyped during the index admission. The median time from genotype order to result was 1 day, and 75% of results were available by the day after PCI. Among genotyped patients, 263 (30.2%) carried either one (IM) or two (PM) LOF alleles; 262 of which carried the *2 allele (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. P2Y12 inhibitor maintenance therapy by CYP2C19 status.

(A) Study population summary by CYP2C19 genotype availability, loss-of-function (LOF) allele status, and maintenance therapy. (B) CYP2C19 phenotype distribution in genotyped patients: ultrarapid (UM: n=40; 4.6%), rapid (RM: n=196; 22.6%), normal (NM: n=369; 42.5%), intermediate (IM: n=239; 27.5%); poor (PM: n=24; 2.8%) metabolizers The IM [*1/*2=190 (21.9%), *1/*3=1 (0.1%), *2/*17=48 (5.5%), *3/*17=0 (0%)] and PM [*2/*2=24 (2.8%), *2/*3=0 (0%), *3/*3=0 (0%)] phenotypes included multiple genotypes. (C) Maintenance therapy distribution (clopidogrel, prasugrel, or ticagrelor) by CYP2C19 status (NG, not genotyped).

Clinical factors indicative of high risk, including an ACS indication for PCI (OR 2.56, 95% CI 1.94–3.38, P<0.001) and stent placement in either the left anterior descending (LAD) (OR 1.60, 95% CI 1.21–2.13, P=0.001) or left main (OR 4.72, 95% CI 1.57–20.5, P=0.004) coronary artery, were significant predictors of CYP2C19 genotype testing during the index PCI hospitalization. In contrast, patients receiving chronic P2Y12 inhibitor therapy upon admission were significantly less likely to have a genotype test ordered (Supplemental Table 1).

P2Y12 Inhibitor Therapy Selection

Clopidogrel (69.4%) was the most commonly prescribed maintenance therapy with prasugrel (30.6%) and ticagrelor (3.3%) prescribed less frequently. Consistent with the algorithm, this distribution differed substantially by CYP2C19 phenotype status (Figure 1C). CYP2C19 IMs and PMs were routinely prescribed either prasugrel (59.9%) or ticagrelor (11.8%) as maintenance therapy, with 69.5% of IMs and 83.3% of PMs receiving alternative antiplatelet therapy. In contrast, clopidogrel was commonly prescribed in patients without a CYP2C19 LOF allele (76.4%) or without an available CYP2C19 genotype (88.9%).

Predictors of P2Y12 Inhibitor Therapy Selection

Clinical factors associated with prasugrel/ticagrelor selection as the initial loading therapy during the index PCI are described in Supplemental Table 2. CYP2C19 IM or PM phenotype was a significant independent predictor of prasugrel/ticagrelor selection as maintenance therapy (OR 13.1, 95% CI 8.84–19.7, P<0.001; Supplemental Table 3), as well as a change in therapy from clopidogrel to alternative therapy after the index PCI procedure (Supplemental Figure 2). Clinical factors, including an ACS indication for PCI (OR 2.80, 95% CI 1.93–4.12, P<0.001), LAD artery stent (OR 1.64, 95% CI 1.16–2.34, P=0.005) and prasugrel/ticagrelor use upon admission (OR 18.5, 95% CI 5.75–84.4, P<0.001), were also significantly associated with prasugrel/ticagrelor selection; whereas elevated bleeding risk and clopidogrel use on admission were significantly associated with clopidogrel selection (Supplemental Table 3).

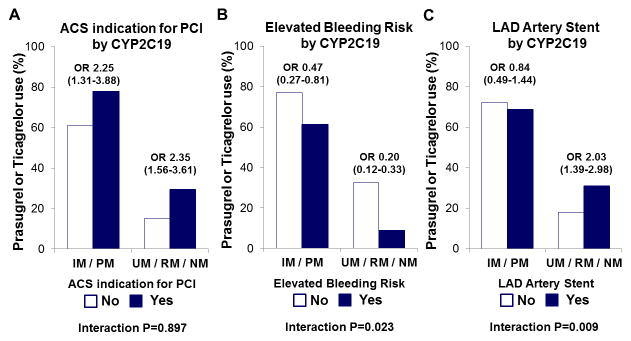

CYP2C19 phenotype status also appeared to modify the association between certain clinical factors and antiplatelet therapy selection (Supplemental Table 4). Although the association between ACS indication for PCI and prasugrel/ticagrelor selection was not modified by CYP2C19 phenotype status (Figure 2A), the association between elevated bleeding risk and a lower likelihood of prescribing prasugrel/ticagrelor was more pronounced in patients without a CYP2C19 LOF allele (OR 0.20, 95% CI 0.12–0.33) compared to IM/PMs (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.27–0.81; interaction P=0.023; Figure 2B). The association between LAD artery stent placement and prasugrel/ticagrelor selection was only evident in patients without a LOF allele (interaction P=0.009; Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Prasugrel or ticagrelor selection by clinical factor and CYP2C19 phenotype status.

The frequency of alternative therapy (prasugrel or ticagrelor) use as maintenance therapy (y-axis) in the strata of CYP2C19 intermediate or poor metabolizers (IM/PM) and ultrarapid, rapid or normal metabolizers (UM/RM/NM) is presented according to the absence (No) and presence (Yes) of the following clinical factors: (A) acute coronary syndrome (ACS) indication for PCI; (B) elevated bleeding risk; (C) left anterior descending (LAD) artery stent placement. The odds ratio (95% CI) for the association between presence of the clinical factor with prasugrel/ticagrelor selection within each CYP2C19 phenotype strata (IM/PM or UM/RM/NM), and the CYP2C19 phenotype*clinical factor interaction P-value is provided.

Clinical Outcomes

Clinical outcomes were evaluated in 999 patients with follow-up available after the index PCI admission (83.7% of the study population). The median (IQR) time from index PCI to MACCE or last follow-up was 8.7 (4.4–11.1) months. During follow-up, 119 (11.9%; 18.9 per 100 patient-years) and 38 (3.8%; 6.1 per 100 patient-years) experienced MACCE and clinically significant bleeding events, respectively. Event frequencies were lower in the strata of patients that did not undergo CYP2C19 genotyping (Table 2), which was expected since the algorithm only recommended genotyping in high-risk patients.

Table 2.

Cardiovascular and bleeding event type by CYP2C19 status and P2Y12 inhibitor.

| Event type | Not genotyped | Genotyped | CYP2C19 IM/PM | CYP2C19 UM/RM/NM | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | All | Clopidogrel | Pras/Ticag | Clopidogrel | Pras/Ticag | |

| N=248 | N=751 | N=68 * | N=165 | N=405 | N=113 | |

| MACCE | 24 (9.7%) | 95 (12.6%) | 18 (26.5%) | 13 (7.9%) | 53 (13.1%) | 11 (9.7%) |

| Death | 9 (3.6%) | 22 (2.9%) | 5 (7.7%) | 4 (2.4%) | 12 (3.0%) | 1 (0.9%) |

| Myocardial infarction | 5 (2.0%) | 29 (3.9%) | 5 (7.7%) | 5 (3.0%) | 16 (4.0%) | 3 (2.7%) |

| Stent Thrombosis | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (0.4%) | 1 (1.5%) | 1 (0.6%) | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Acute coronary syndrome/unstable angina | 10 (4.0%) | 44 (5.9%) | 8 (11.8%) | 5 (3.0%) | 24 (5.9%) | 7 (6.2%) |

| Ischemic cerebrovascular accident | 3 (1.2%) | 4 (0.5%) | 1 (1.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (0.5%) | 1 (0.9%) |

| Transient ischemic attack | 1 (0.4%) | 5 (0.7%) | 1 (1.5%) | 1 (0.6%) | 2 (0.5%) | 1 (0.9%) |

| Clinically significant bleeding events | 7 (2.8%) | 31 (4.1%) | 2 (3.0%) | 7 (4.2%) | 19 (4.7%) | 3 (2.7%) |

| GUSTO moderate | 4 (1.6%) | 14 (1.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (2.4%) | 11 (2.7%) | 2 (1.8%) |

| GUSTO severe | 3 (1.2%) | 17 (2.3%) | 2 (3.0%) | 3 (1.8%) | 16 (4.0%) | 1 (0.9%) |

Data are presented as the number (percentage) of patients in each group that experienced the event over the course of follow-up.

One patient with a CYP2C19 IM phenotype receiving treatment with prasugrel experienced an early bleeding event, and was subsequently switched to clopidogrel for the remainder of follow-up.

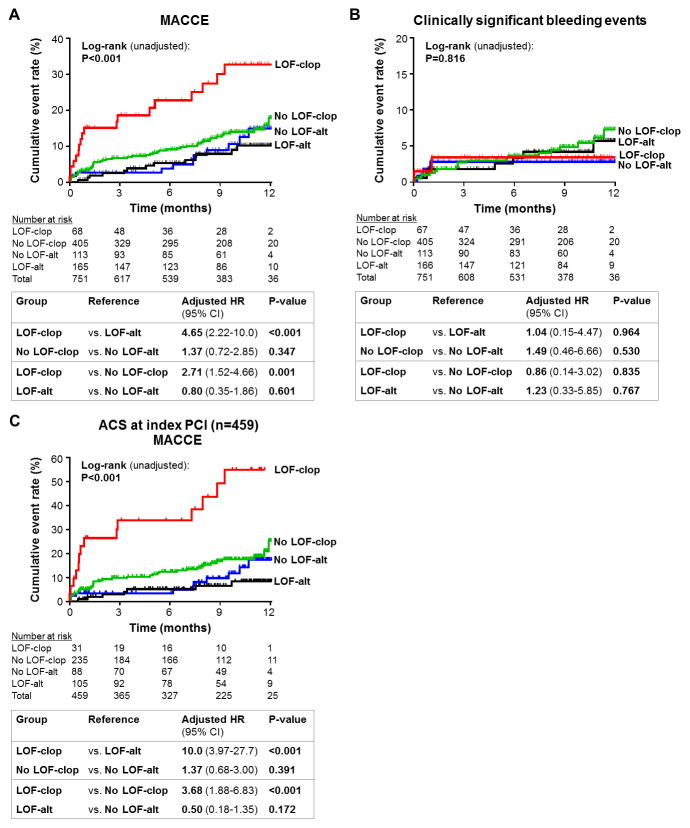

The risk of developing MACCE was significantly associated with CYP2C19 phenotype and the prescribed antiplatelet therapy (Table 3). Compared to CYP2C19 IM/PMs treated with alternative therapy, IM/PMs treated with clopidogrel exhibited a significantly higher risk of MACCE (11.4 vs. 52.0 events per 100 patient-years, respectively; Figure 3A; adjusted HR 4.65, 95% CI 2.22–10.0, P<0.001). In contrast, no significant difference in MACCE was observed in CYP2C19 UM/RM/NMs treated with clopidogrel relative to alternative therapy (adjusted HR 1.37, 95% CI 0.72–2.85, P=0.347; CYP2C19*antiplatelet interaction P=0.018). There was no difference in risk of developing a clinically significant bleeding event across the CYP2C19 phenotype and antiplatelet therapy groups (Figure 3B, Table 3).

Table 3.

Cardiovascular and bleeding event incidence by CYP2C19 status and P2Y12 inhibitor.

| Clinical outcome by CYP2C19 phenotype–selected P2Y12 inhibitor | Event No. (%)* | Event rate (per 100 pt-yrs)† | Log-rank P‡ (unadjusted) | Log-rank P‡ (adjusted) | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MACCE | ||||||

| IM/PM–Alternative | 13 (7.9%) | 11.4 | Reference | |||

| IM/PM–Clopidogrel | 18 (26.5%) | 52.0 | 4.65 (2.22–10.0) | <0.001 | ||

| UM/RM/NM–Alternative | 11 (9.7%) | 15.0 | 1.25 (0.54–2.83) | 0.601 | ||

| UM/RM/NM–Clopidogrel | 53 (13.1%) | 20.1 | P<0.001 | P<0.001 | 1.71 (0.95–3.32) | 0.075 |

| Clinically significant bleeding events | ||||||

| IM/PM–Alternative | 7 (4.2%) | 6.2 | Reference | |||

| IM/PM–Clopidogrel | 2 (3.0%) | 5.9 | 1.04 (0.15–4.47) | 0.964 | ||

| UM/RM/NM–Alternative | 3 (2.7%) | 4.2 | 0.81 (0.17–3.03) | 0.767 | ||

| UM/RM/NM–Clopidogrel | 19 (4.7%) | 7.3 | P=0.816 | P=0.925 | 1.21 (0.51–3.19) | 0.675 |

The number (percentage) in each group that experienced an event during follow-up.

The event rate was calculated as the number of events per 100 patient-years of follow-up.

Comparison of outcomes across the four CYP2C19 phenotype and antiplatelet therapy groups. Stratified analysis of MACCE in African-Americans (adjusted log-rank P=0.038) and non-African-Americans (adjusted log-rank P=0.041) demonstrated that no racial/ethnic-based differences were present. The small number of bleeding events precluded race-stratified analysis of bleeding.

Figure 3. Cardiovascular and bleeding outcomes following PCI by CYP2C19 status and P2Y12 inhibitor therapy.

Kaplan-Meier curves for (A) major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular event (MACCE) and (B) clinically significant bleeding event incidence in patients that underwent CYP2C19 testing and had follow-up available after the index PCI admission (N=751). (C) Kaplan-Meier curve for MACCE in the strata of patients presenting with an ACS indication for PCI (n=459). Data are shown across four CYP2C19 genotype and antiplatelet therapy strata: intermediate or poor metabolizers carrying a loss-of-function allele prescribed clopidogrel (LOF-clop), LOF allele carriers prescribed alternative therapy (LOF-alt), ultrarapid, rapid or normal metabolizers without a LOF allele prescribed clopidogrel (No LOF-clop); patients without a LOF prescribed alternative therapy (No LOF-alt). The unadjusted log rank P-value for outcomes across the four groups, and the adjusted HR, 95% CI and P-value for the indicated between-group comparisons, are provided.

In patients with an ACS indication for their index PCI, the risk of MACCE was highest in the CYP2C19 IM/PMs treated with clopidogrel consistent with the overall study population (Figure 3C, Supplemental Table 5). Bleeding event rates were similar across the CYP2C19 phenotype and antiplatelet therapy groups in the ACS strata (Supplemental Table 5).

Sustainability of Genotype-Guided Antiplatelet Therapy over Time

The frequency of CYP2C19 testing and use of alternative therapy in IM/PMs varied significantly throughout the study period. Following a very high rate of genotyping during the initial 6 months (88%), the proportion genotyped decreased during the subsequent 12 months (61–65%) and then increased (78%) during the final 6 months (Figure 4A). These differences were driven by the frequency of genotype testing during the index PCI admission (Supplemental Table 6).

Figure 4. Frequency of CYP2C19 genotype testing and P2Y12 inhibitor maintenance therapy selection by CYP2C19 status over time.

The index PCI date was categorized into 6-month intervals. The frequency of (A) CYP2C19 genotype testing and (B) alternative therapy (prasugrel or ticagrelor) use in the strata of CYP2C19 intermediate or poor metabolizers (IM/PM) and ultrarapid, rapid or normal metabolizers (UM/RM/NM) in each time interval was compared. The chi-squared P-value is provided.

The frequent use of alternative therapy in CYP2C19 IM/PMs during the initial 6 months (83%) was sustained during the subsequent 6-month period, but declined to 54% before increasing to 68% during the final 6 months (Figure 4B). This was accompanied by a significant decline in the proportion of IM/PMs that underwent a change in therapy from clopidogrel to alternative therapy (Supplemental Table 6). In contrast, no significant difference in alternative therapy use over time was observed in those without a CYP2C19 LOF allele (Figure 4B).

DISCUSSION

The current investigation evaluated use of CYP2C19 testing, P2Y12 inhibitor selection and clinical outcomes following implementation of genotype-guided antiplatelet therapy over a 2-year period at a single academic medical center. Results showed that CYP2C19 genotypes were frequently ordered, efficiently returned and routinely used to guide P2Y12 inhibitor selection after PCI. The use of clopidogrel in CYP2C19 IM/PMs was associated with a significantly higher risk of MACCE compared to alternative therapy, consistent with results from the multi-center IGNITE Network study.19 The current study also demonstrates that the frequency of genotype testing at the time of PCI and use of alternative therapy in CYP2C19 IM/PMs varied significantly over time. Taken together, these data illustrate that implementing a CYP2C19-guided antiplatelet therapy algorithm is feasible, sustainable and associated with better clinical outcomes in a real-world clinical practice but challenging to maintain at a consistently high level of fidelity.

Recently, an investigation of outcomes in 1,815 patients across 7 U.S. centers conducted by the IGNITE Network demonstrated that CYP2C19 IM/PMs prescribed clopidogrel had a 2.26-fold higher risk for MACCE after PCI compared to those prescribed alternative therapy.19 Our results, and those of the IGNITE study, are consistent with retrospective genetic analyses that have repeatedly demonstrated higher risk for MACCE in CYP2C19 IM/PMs treated with clopidogrel after PCI.6–8 It is important to note that 572 of the 868 genotyped patients in our single-center analysis were included in the multi-center IGNITE Network investigation. The current study extends those results, shows no difference in clinically significant bleeding across genotypes, and demonstrates that the fidelity in which CYP2C19-guided antiplatelet therapy is applied in practice can vary significantly over time. Our results are also consistent with three international prospective studies, which demonstrated that CYP2C19 genotype-guided intensification of antiplatelet therapy in IMs and PMs significantly reduced MACCE compared to conventional therapy without genotyping and did not increase risk for bleeding.20–22 Collectively, these studies provide an expanding evidence base demonstrating that genotype-guided selection of DAPT after PCI is associated with lower rates of MAACE without any increase in clinically significant bleeding. An ongoing randomized controlled clinical trial will assess the utility of CYP2C19-guided antiplatelet therapy in a prospective fashion in approximately 5,000 patients undergoing PCI, but will not be completed until 2020 (NCT01742117).

The American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association PCI guidelines state that genetic testing and use of alternative therapy in genetically predisposed nonresponders “might be considered” in high-risk patients (Class IIb, Level of Evidence: C).1 The FDA black box warning in the clopidogrel label specifically warns prescribers of reduced clopidogrel effectiveness in PMs.16,17 The majority (20 of 24) of PMs at our institution received alternative therapy, and virtually all (17 of 18) MACCE events observed in IM/PMs treated with clopidogrel occurred in IMs. These data are consistent with the IGNITE Network results,19 demonstrate that the elevated risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes is not limited to PMs, and support the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium recommendation to use alternative therapy in CYP2C19 IMs and PMs if CYP2C19 genotype is known.5 Furthermore, the elevated risk of MACCE in CYP2C19 IM/PMs prescribed clopidogrel was most evident in patients that underwent PCI for an ACS indication, which is consistent with the multi-center IGNITE Network results.19 These data are also consistent with prior retrospective analyses that have demonstrated the strongest associations between CYP2C19 LOF alleles and risk of MACCE occur in higher risk strata of patients prescribed clopidogrel, such as PCI versus non-PCI and ACS versus non-ACS indications.9,28 Collectively, our results suggest that (1) clinicians need to be aware of the risks associated with use of clopidogrel in CYP2C19 IMs and PMs, and (2) genotype-guided selection of antiplatelet therapy, with use of alternative therapy in CYP2C19 IMs and PMs, should be considered in high-risk patients undergoing PCI. Due to the low number of events, the clinical impact of genotyping in patients undergoing PCI for a non-ACS indication remains unclear and will require further study.

We observed that clinical factors indicative of high risk for future cardiovascular events, including an ACS indication for PCI and placement of a LAD or left main artery stent, were the strongest predictors of genotype testing during the index PCI admission. These findings illustrate that the interventional cardiologist’s decision to genotype is reactive following risk stratification, consistent with the algorithm. CYP2C19 phenotype was the strongest predictor of antiplatelet therapy selection, indicating that CYP2C19 genotype was frequently used to guide the prescribing decision when available. However, clinical factors such as an ACS indication for PCI, risk factors for bleeding, and prior P2Y12 inhibitor use on admission were also significantly associated with DAPT selection. Moreover, the presence of risk factors for bleeding significantly modified the association between the CYP2C19 result and medication selection. These data illustrate that, although important, the genotype result is one of multiple factors considered when selecting DAPT in a real-world setting, and clinicians may be reluctant to prescribe alternative therapy in IM/PMs with risk factors for bleeding. However, the significantly lower risk of MACCE observed in CYP2C19 IM/PMs prescribed alternative therapy compared to clopidogrel was not offset by a higher risk of bleeding events, which were similar across CYP2C19 phenotype and DAPT groups and consistent with other recent prospective studies.20–22 These data suggest that the ischemic risk conferred by clopidogrel use in IM/PMs may outweigh the risk for clinically significant bleeding events conferred by alternative therapy, and that placing greater weight on a CYP2C19 IM/PM result during the prescribing decision may be warranted in certain cases.

Although the feasibility of clinically implementing genotype-guided antiplatelet therapy has been demonstrated,23,26,29,30 the sustainability of obtaining, interpreting and using CYP2C19 genotype to guide P2Y12 inhibitor selection over time has not been investigated. We observed a high overall frequency of CYP2C19 testing (73% of all PCI patients; 81% of ACS patients) and use of alternative therapy in CYP2C19 IM/PMs (71% of all PCI patients; 78% of ACS patients). The feasible implementation and sustainable use of a genotype-guided algorithm at our institution was possible due to several key factors that alleviated logistical barriers. Notably, in-house genotype testing with prompt turnaround of results in the EHR, and interdisciplinary collaboration and communication among physicians, clinical pharmacists and nurses has proven critical. Indeed, pharmacists are essential to the successful application of pharmacogenomics in clinical practice.31 Despite the high overall use of genotype-guided antiplatelet therapy, we also observed that the proportion of PCI patients genotyped and IM/PMs prescribed alternative therapy significantly varied over time. The latter appeared driven by a significant decline in IM/PMs that underwent a change from clopidogrel to alternative therapy. These results demonstrate that implementation of an algorithm that uses genetic testing to guide drug selection is difficult to sustain at a high level in clinical practice. Since evaluation of barriers to sustained implementation via provider surveys was beyond the scope of the current study, it remains unclear what specific factors contributed to the observed fluctuations in fidelity. Although recurrent clinician education was employed, automated clinical decision support (CDS) within the EHR to alert clinicians about the genotype result was not available at our institution during the study period. Clinician education and CDS have been proposed as key solutions to facilitate fidelity, sustainability and scale of genotype-guided prescribing within and across sites.32 Future studies are needed to evaluate the direct benefits of these strategies to overcome key implementation barriers.

The costs associated with CYP2C19 genetic testing are also an important consideration. Recent cost-effectiveness analyses have estimated a per patient cost of $100–350, and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) 2017 Clinical Laboratory Fee Schedule reports a reimbursement amount of $293 for CYP2C19 testing.33,34 These studies have collectively concluded that, from a third-party payer’s perspective, CYP2C19 genotype-guided antiplatelet therapy after PCI may be a cost-effective strategy over one-year and lifetime horizons when compared to either universal clopidogrel or universal prasugrel or ticagrelor treatment without genotype testing.33 The short-term cost-effectiveness of a genotype-guided strategy over the first 30 days following PCI has also been recently described.34 However, these analyses have been limited by their use of clinical outcome data derived from retrospective genetic analyses of registries and clinical trials. Future studies are needed to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of implementing CYP2C19 genotype-guided antiplatelet therapy from the health system perspective using clinical outcome and cost data derived from real-world clinical practice.

It is important to acknowledge several limitations with our study. First, data collection was completed retrospectively via EHR abstraction. Although retrospective data collection minimized influence on the practice under evaluation, we were unable to conclusively determine whether clopidogrel use in IM/PMs was a conscious clinical decision or failure to acknowledge the genotyping result. Second, genotype-guided therapy was not randomized. Thus, we cannot exclude the influence of bias or attribute cause-and-effect to the observed associations between CYP2C19 phenotype, DAPT selection, and outcomes. In order to lessen the potential confounding effects related to differences across groups, covariate-adjusted and stratified analysis were conducted; however, residual confounding may remain and the magnitude of the observed association between clopidogrel use in IM/PMs and risk of MACCE should be interpreted with caution. Third, the analysis is based on medications prescribed, but there is no available data on adherence. Lastly, the data presented reflects the experience with genotype-guided antiplatelet therapy at a single academic medical center, and the results may not be generalizable to other settings and populations. Future studies in larger and more diverse populations are warranted.

Conclusions

The adverse cardiovascular outcomes associated with clopidogrel use in patients with a CYP2C19 LOF allele suggest that the use of genotype-guided antiplatelet therapy in practice may significantly improve clinical outcomes. Given the increasing number of institutions that seek to clinically implement genotype-guided antiplatelet therapy,23–25 our results offer insight into the feasibility, sustainability and clinical impact of using a CYP2C19 genotyping strategy to optimize P2Y12 inhibitor selection in PCI patients.

Supplementary Material

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE.

CYP2C19 loss-of-function (LOF) alleles impair clopidogrel effectiveness after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). However, there remains considerable debate and uncertainty surrounding whether CYP2C19 genetic testing should be used clinically to guide antiplatelet therapy selection in PCI patients. The current investigation offers novel insight into the feasibility, sustainability and clinical impact of using a CYP2C19 genotyping strategy to optimize P2Y12 inhibitor selection following PCI in a real-world clinical setting. Results showed that CYP2C19 genotypes were frequently ordered, efficiently returned, and routinely used to guide P2Y12 inhibitor selection after PCI over a 2-year period; however, the frequency of genotype testing and use of alternative therapy in CYP2C19 intermediate and poor metabolizers (IM/PMs) varied significantly over time. The current study also showed that use of clopidogrel in CYP2C19 IM/PMs was associated with a significantly higher risk of major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) compared to alternative therapy. Our results demonstrate that implementing a CYP2C19 genotype-guided antiplatelet therapy algorithm is feasible, sustainable and associated with better clinical outcomes in a real-world clinical setting, but challenging to maintain at a consistently high level of fidelity. The clinical implications of our findings are that (1) clinicians need to be aware of the increased risk of MACCE associated with use of clopidogrel in PCI patients that carry either one or two copies of a CYP2C19 LOF allele, and (2) genotype-guided selection of antiplatelet therapy, with use of alternative therapy in CYP2C19 IMs/PMs, should be considered in high-risk patients undergoing PCI.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the UNC Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory and the UNC Molecular Genetics Laboratory staff for their important contributions. We also thank our partners in the IGNITE Network, a consortium of genomic medicine pilot demonstration projects funded and guided by the NHGRI, (https://ignite-genomics.org/) for their valuable contributions. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NHGRI or NIH.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES: None

References

- 1.Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, Bailey SR, Bittl JA, Cercek B, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Circulation. 2011;124:e574–651. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823ba622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brilakis ES, Patel VG, Banerjee S. Medical management after coronary stent implantation: a review. JAMA. 2013;310:189–198. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.7086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fan W, Plent S, Prats J, Deliargyris EN. Trends in P2Y12 inhibitor use in patients referred for invasive evaluation of coronary artery disease in contemporary US practice. Am J Cardiol. 2016;117:1439–1443. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sherwood MW, Wiviott SD, Peng SA, Roe MT, Delemos J, Peterson ED, et al. Early clopidogrel versus prasugrel use among contemporary STEMI and NSTEMI patients in the US: insights from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e000849. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.000849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scott SA, Sangkuhl K, Stein CM, Hulot JS, Mega JL, Roden DM, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guidelines for CYP2C19 genotype and clopidogrel therapy: 2013 update. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;94:317–323. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2013.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mega JL, Close SL, Wiviott SD, Shen L, Hockett RD, Brandt JT, et al. Cytochrome p-450 polymorphisms and response to clopidogrel. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:354–362. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mega JL, Simon T, Collet JP, Anderson JL, Antman EM, Bliden K, et al. Reduced-function CYP2C19 genotype and risk of adverse clinical outcomes among patients treated with clopidogrel predominantly for PCI: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;304:1821–1830. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wallentin L, James S, Storey RF, Armstrong M, Barratt BJ, Horrow J, et al. Effect of CYP2C19 and ABCB1 single nucleotide polymorphisms on outcomes of treatment with ticagrelor versus clopidogrel for acute coronary syndromes: a genetic substudy of the PLATO trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1320–1328. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61274-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sorich MJ, Rowland A, McKinnon RA, Wiese MD. CYP2C19 genotype has a greater effect on adverse cardiovascular outcomes following percutaneous coronary intervention and in Asian populations treated with clopidogrel: a meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2014;7:895–902. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.114.000669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mega JL, Close SL, Wiviott SD, Shen L, Hockett RD, Brandt JT, et al. Cytochrome P450 genetic polymorphisms and the response to prasugrel: relationship to pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic, and clinical outcomes. Circulation. 2009;119:2553–2560. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.851949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, Cannon CP, Emanuelsson H, Held C, et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1045–1057. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, Montalescot G, Ruzyllo W, Gottlieb S, et al. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2001–2015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hochholzer W, Wiviott SD, Antman EM, Contant CF, Guo J, Giugliano RP, et al. Predictors of bleeding and time dependence of association of bleeding with mortality: insights from the Trial to Assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by Optimizing Platelet Inhibition With Prasugrel--Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 38 (TRITON-TIMI 38) Circulation. 2011;123:2681–2689. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.002683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DiNicolantonio JJ, D’Ascenzo F, Tomek A, Chatterjee S, Niazi AK, Biondi-Zoccai G. Clopidogrel is safer than ticagrelor in regard to bleeds: a closer look at the PLATO trial. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:1739–1744. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.06.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sorich MJ, Vitry A, Ward MB, Horowitz JD, McKinnon RA. Prasugrel vs. clopidogrel for cytochrome P450 2C19-genotyped subgroups: integration of the TRITON-TIMI 38 trial data. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:1678–1684. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holmes DR, Jr, Dehmer GJ, Kaul S, Leifer D, O’Gara PT, Stein CM. ACCF/AHA clopidogrel clinical alert: approaches to the FDA “boxed warning”: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on clinical expert consensus documents and the American Heart Association. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:321–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roden DM, Shuldiner AR. Responding to the clopidogrel warning by the US Food and Drug Administration: real life is complicated. Circulation. 2010;122:445–448. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.973362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nissen SE. Pharmacogenomics and clopidogrel: irrational exuberance? JAMA. 2011;306:2727–2728. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cavallari LH, Lee CR, Beitelshees AL, Cooper-DeHoff RM, Duarte JD, Voora D, et al. Multisite investigation of outcomes with implementation of CYP2C19 genotype-guided antiplatelet therapy after percutaneous coronary intervention. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:181–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2017.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen DL, Wang B, Bai J, Han Q, Liu C, Huang XH, et al. Clinical value of CYP2C19 genetic testing for guiding the antiplatelet therapy in a Chinese population. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2016;67:232–236. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xie X, Ma YT, Yang YN, Li XM, Zheng YY, Ma X, et al. Personalized antiplatelet therapy according to CYP2C19 genotype after percutaneous coronary intervention: a randomized control trial. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:3736–3740. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanchez-Ramos J, Davila-Fajardo CL, Toledo Frias P, Diaz Villamarin X, Martinez-Gonzalez LJ, Martinez Huertas S, et al. Results of genotype-guided antiplatelet therapy in patients who undergone percutaneous coronary intervention with stent. Int J Cardiol. 2016;225:289–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.09.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Empey PE, Stevenson JM, Tuteja S, Weitzel KW, Angiolillo DJ, Beitelshees AL, et al. Multi-site investigation of strategies for the implementation of CYP2C19 genotype-guided antiplatelet therapy. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2017 doi: 10.1002/cpt.1006. epub ahead of print Dec 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cavallari LH, Beitelshees AL, Blake KV, Dressler LG, Duarte JD, Elsey A, et al. The IGNITE Pharmacogenetics Working Group: An Opportunity for Building Evidence with Pharmacogenetic Implementation in a Real-World Setting. Clin Transl Sci. 2017;10:143–146. doi: 10.1111/cts.12456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luzum JA, Pakyz RE, Elsey AR, Haidar CE, Peterson JF, Whirl-Carrillo M, et al. The Pharmacogenomics Research Network Translational Pharmacogenetics Program: outcomes and metrics of pharmacogenetic implementations across diverse healthcare systems. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2017;102:502–510. doi: 10.1002/cpt.630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee JA, Lee CR, Reed BN, Plitt DC, Polasek MJ, Howell LA, et al. Implementation and evaluation of a CYP2C19 genotype-guided antiplatelet therapy algorithm in high-risk coronary artery disease patients. Pharmacogenomics. 2015;16:303–313. doi: 10.2217/pgs.14.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mehran R, Rao SV, Bhatt DL, Gibson CM, Caixeta A, Eikelboom J, et al. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials: a consensus report from the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium. Circulation. 2011;123:2736–2747. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.009449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim HS, Chang K, Koh YS, Park MW, Choi YS, Park CS, et al. CYP2C19 poor metabolizer is associated with clinical outcome of clopidogrel therapy in acute myocardial infarction but not stable angina. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2013;6:514–521. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.113.000109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weitzel KW, Elsey AR, Langaee TY, Burkley B, Nessl DR, Obeng AO, et al. Clinical pharmacogenetics implementation: approaches, successes, and challenges. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2014;166C:56–67. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peterson JF, Field JR, Unertl KM, Schildcrout JS, Johnson DC, Shi Y, et al. Physician response to implementation of genotype-tailored antiplatelet therapy. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;100:67–74. doi: 10.1002/cpt.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Owusu-Obeng A, Weitzel KW, Hatton RC, Staley BJ, Ashton J, Cooper-Dehoff RM, et al. Emerging roles for pharmacists in clinical implementation of pharmacogenomics. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34:1102–1112. doi: 10.1002/phar.1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bell GC, Crews KR, Wilkinson MR, Haidar CE, Hicks JK, Baker DK, et al. Development and use of active clinical decision support for preemptive pharmacogenomics. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21:e93–99. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2013-001993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang M, You JH. Review of pharmacoeconomic evaluation of genotype-guided antiplatelet therapy. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2015;16:771–779. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2015.1013028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Borse MS, Dong OM, Polasek MJ, Farley JF, Stouffer GA, Lee CR. CYP2C19-guided antiplatelet therapy: a cost-effectiveness analysis of 30-day and 1-year outcomes following percutaneous coronary intervention. Pharmacogenomics. 2017;18:1155–1166. doi: 10.2217/pgs-2017-0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.