Abstract

Adolescents’ negative expectations of their peers were examined as predictors of their future selection of hostile partners, in a community sample of 184 adolescents followed from ages 13 to 24. Utilizing observational data, close friend- and self-reports, adolescents with more negative expectations at age 13 were found to be more likely to form relationships with observably hostile romantic partners and friends with hostile attitudes by age 18 even after accounting for baseline levels of friend hostile attitudes at age 13 and adolescents’ own hostile behavior and attitudes. Furthermore, the presence of friends with hostile attitudes at age 18 in turn predicted higher levels of adult friend hostile attitudes at age 24. Results suggest the presence of a considerable degree of continuity from negative expectations to hostile partnerships from adolescence well into adulthood.

Keywords: social expectations, romantic relationships, observational coding, hostility, adult outcomes

Hostility and high levels of conflict within relationships have repeatedly been linked to problematic outcomes for those involved. Hostility may escalate to physical aggression, but it can manifest in several other ways, including threatening body language, pressuring speech, personal attacks, angry refusal to discuss a disagreement, or aggressive and demeaning attitudes toward others. Physical health correlates of hostility range from specific physiological changes, such as increased blood pressure and alterations in immune functioning, to coronary heart disease, and even early mortality (Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001; Linder, Crick, & Collins, 2002; Luecken & Roubinov, 2012; Miller, Smith, Turner, Guijarro, & Hallet, 1996). Hostility within relationships has also been found to predict increasing anxiety and depression over time (Bertera, 2005; Cranford, 2004). Yet we have relatively little information to explain why some individuals repeatedly become involved with hostile peer and romantic partners across the life course (Linder & Collins, 2005; Stocker & Richmond, 2007).

Multiple lines of developmental research, from childhood to adulthood, converge on the idea that the expectations that people bring to new social situations, which guide their choice of partners, provide one possible mechanism that may account for the tendency of some individuals to repeatedly find themselves in relationships with hostile partners. Individuals who expect others to treat them badly might accept or even select for such negative behavior from partners based on these expectations. Attachment theory stresses the importance of earlier experiences in shaping mental representations of existing close relationships. These representations may then be carried forward to new relationships (N. L. Collins & Read, 1994; Dykas, Ziv, & Cassidy, 2008). Individuals may select partners and/or elicit behaviors from partners (not necessarily consciously) that confirm these pre-existing representations (Cassidy, 2000; Feeney, Cassidy, & Ramos-Marcuse, 2008). For example, attachment styles predict selection of similar partners and reinforcement of existing attachment styles, and relationship behaviors (Dinero, Conger, Shaver, Widaman, & Larsen-Rife, 2011; Strauss, Morry, & Kito, 2012). Similarly, cumulative continuity theory suggests that individuals maintain relationship patterns by choosing environments or people that fit their pre-existing expectations. Through these choices, individuals reinforce existing patterns of behaviors and expectations over time (Caspi, Bem, & Elder, 1989; Caspi, Elder, & Bem, 1988). Longitudinal research suggests that individuals often repeatedly select into similar types of relationships, even when these relationships are characterized by hostility (Carbone-Lopez, Rennison, & Macmillan, 2012; Cui, Ueno, Gordon, & Fincham, 2013). Together, both theories support the notion that expectations for others’ behavior can create self-fulfilling prophecies, with potentially powerful implications for partner selection and relationships going forward (Merton, 1948).

Adolescence appears as a potentially critical point in development regarding both negative social expectations and the development of hostile relationship patterns. In adolescence, as peer relationships become more central (Allen & Land, 1999; W. A. Collins, 1997), the expectations and behaviors teens bring to these relationships may set trajectories of partner selection that will shape social relationships into adulthood. Negative social expectations—defined here as the cognitive expectation that others will react with negativity in ambiguous social situations—have been associated with higher levels of depression (Gregory et al., 2007), more insecure attachment to parents (Liu, 2008), and higher levels of peer rejection (Rudolph, Hammen, & Burge, 1997).

Unfortunately, direct studies of the implications of negative social expectations for future social development have been rare. Though distinct from negative expectations, the related constructs of hostile attribution biases and rejection sensitivity do provide support for the potential role of such expectations in the development of hostile relationships. Studies in childhood have consistently found that the attribution of hostile intent to others has been linked to both the development of aggressive behavior, and to victimization from other children, suggesting a potential cycle of expectations, behavior, and elicited responses that contributes to negative outcomes (Dodge et al., 2003; Vitaro, Brendgen, & Tremblay, 2002). Similarly, expectations of, and anticipated distress from, rejection in adolescence and adulthood have been linked to hostility from participants and subsequent rejection from romantic partners in short-term research (Downey & Feldman, 1996; Downey, Freitas, Michaelis, & Khouri, 1998; Purdie & Downey, 2000). Previous work using the current study sample has found that rejection sensitivity is linked to decreases in peer-reported social competence, that rejection sensitivity amplifies a link between hostility in relationships and depressive symptoms, and that rejection sensitive individuals are more likely to have negative romantic relationships and to behave submissively in such relationships (Chango, McElhaney, Allen, Schad, & Marston, 2012; Hafen, Spilker, Chango, Marston, & Allen, 2014; Marston, Hare, & Allen, 2010). However, the possibility that individuals with negative expectations might select partners who behave in a hostile manner has not been previously examined.

There is some research to suggest that characteristics of prior relationships other than similarity may also predict partner selection: Previous observational research has found that both intrusive parental behaviors and poorer quality friend relationships in adolescence predict later romantic partner hostility, which is consistent with the notion that adolescents learn ways of relating to others from earlier relationships (Linder & Collins, 2005). However, we know little about how or even whether this cycle of partner hostility may play out from adolescence to adulthood, and across different types of relationships.

According to attachment and cumulative continuity theories, even individuals who are not hostile themselves may be more likely to select partners who confirm negative relationship expectations from prior experiences (Carbone-Lopez et al., 2012; Cui et al., 2013; Dinero et al., 2011; Strauss et al., 2012). This expectation confirming effect should be distinguished from two other peer processes that also tend to be active during adolescence. One possibility is that adolescents select partners who are similar to themselves in levels of hostility (i.e., homophily) in a type of “niche-seeking” (Bowker et al., 2010). Alternatively hostile adolescents may create hostile relationships in future partners. Disentangling selection of partners who primarily confirm negative expectations from homophily and influence effects can be difficult, but one approach is to control for the target participant’s baseline hostile behavior. By accounting for participant’s baseline hostile behavior, we can account for any effects due to selection of partners based on simple similarity in levels of hostility and effects of participant hostility creating partners’ future hostility (Arriaga & Foshee, 2004). If effects remain between early negative expectations and later partner hostility after controlling for adolescents’ own hostility, this would suggest that adolescents with negative expectations are not merely selecting hostile partners as a result of their own hostility. This would then provide support for the hypothesis that selection of hostile partners is due to the effect of negative social expectations.

Friendships and romantic relationships are the two most salient peer relationships for both adolescents and adults. Close friendships and romantic relationships can both serve attachment functions into adulthood, but friendships tend to be less intense than romantic relationships, especially during late adolescence and adulthood (Carbery & Buhrmester, 1998; Markiewicz, Lawford, Doyle, & Haggart, 2006). Romantic relationships typically involve some degree of conflict and observable negativity, whereas friendships tend to be more harmonious (Creasey, Kershaw, & Boston, 1999; Goldstein, 2011). Observational research with friends and romantic partners finds that romantic relationships are typified by more intense non-verbal behaviors (eye gaze, touching, etc.) than friendships (Guerrero, 1997). Adolescents who expect hostility in relationships may select romantic partners who behave in an observably hostile manner toward them. However, due to the aforementioned differences between friendships and romantic relationships, hostility in a friend may be more subtle, reflected in hostile attitudes toward others rather than observable hostility within the friendship.

Adolescents who expect peers to treat them poorly when they begin dating may act on and sustain these expectations by selecting partners who do in fact treat them with hostility. Research has not yet examined potential romantic partner selection bias with adolescents, nor even with relationships more generally. Evidence suggests that poorer quality peer relationships may lead to more hostility from romantic partners later in adolescence, although the mechanism by which this occurs is unclear (Linder et al., 2002). It may be that earlier poor experiences in relationships lead individuals to develop expectations that partners will display hostile or critical behaviors, and so adolescents with these past experiences may thus be more likely to tolerate those types of behaviors in their next relationship (Alexander, 2009). Similarly, early adolescents with negative expectations of peers may be more likely to select and/or tolerate hostile romantic partners, partially as a fulfillment of those expectations. As they move beyond adolescence, teens with a history of involvement in relationships with partners who confirm negative expectations of others may continue to fulfill these expectations in adult relationships. Current qualities of close friends, such as antisocial behavior and sociability, are known to predict similar characteristics in future friendships (Güroğlu, Cillessen, Haselager, & van Lieshout, 2012), but whether expectations in part may account for these continuities remains unclear, as to date no mechanisms accounting for these continuities have been explored in depth.

This study examined early adolescents’ negative social expectations as a type of self-fulfilling prophecy that may partially explain involvement in later romantic and friend relationships characterized by partner hostility. Adolescents with negative expectations about social situations were hypothesized to be more likely to later select partners whose hostility confirmed those negative expectations, and this selection process was predicted to display continuity over time and across relationships. Specifically, it was hypothesized that

Hypothesis 1: Teens with negative social expectations in early adolescence would be disproportionately likely to select partners who displayed or reported hostility in late adolescence, even after accounting for early adolescent friends’ hostility and participants’ own hostility.

Hypothesis 2: Both early negative social expectations and partner hostility in late adolescence were, in turn, expected to predict the formation of adult partnerships with hostile individuals, again even after accounting for baseline levels of peer hostility and participants’ own hostility.

These predictions were examined within a diverse community sample of adolescents, their romantic partners, and their close friends, who were followed longitudinally over an 11-year period from early adolescence through early adulthood. To ensure that linkages were not simply an artifact of a negative reporting bias on the part of target adolescents, observational- and friend-reports were used to obtain independent assessments of partner hostility in late adolescence and adulthood.

Method

Participants and Procedure

This report is drawn from a larger longitudinal investigation of adolescent social development in familial and peer contexts. The original sample included 184 seventh and eighth graders (86 male and 98 female; age: , SD = 0.64) and their parents. The sample was racially/ethnically and socioeconomically diverse: 107 adolescents (58%) identified themselves as Caucasian, 53 (29%) as African American, 15 (8%) as of mixed race/ethnicity, and nine (5%) as being from other minority groups. Adolescents’ parents reported a median family income in the US$40,000 to US$59,999 range. Adolescents were originally recruited from the seventh and eighth grades at a public middle school drawing from suburban and urban populations in the Southeastern United States. Students were recruited via an initial mailing to all parents of students in the school, along with follow-up contact efforts at school lunches. Adolescents who indicated they were interested in the study were contacted by telephone. Of all students eligible for participation, 63% agreed to participate either as target participants, or as peers providing collateral information.

All interviews took place in private offices within a university academic building. Participating adolescents provided informed assent, and their parents provided informed consent until adolescents were 18 years of age, at which point they provided informed consent. The same assent/consent procedures were used for peers and their parents. Participants, romantic partners, and close friends were paid for their participation.

For the purposes of the present study, data were drawn from three time points: First, at an early adolescent assessment (participant N = 184, participant , SD = 0.64); next, at a late adolescent assessment (participant N = 172, participant , SD = 0.95); and last, at an early adulthood assessment (participant N = 156, participant , SD = 0.97). There were no differences between target participants who did versus did not participate at age 18 on gender, income, or initial levels of variables measured. Participants who did not participate at age 24 had significantly higher levels of aggressive attitudes at age 13 ( , t = 2.22, p = .03). Males were also significantly less likely to participate at age 24. Nineteen males did not participate versus eight females (χ2 = 7.10, p = .008). There were no other differences between those target participants who did versus did not participate at age 24.

At each wave of data collection, participants nominated their close friend to be included in the study. Close friends were defined as “people you know well, spend time with, and whom you talk to about things that happen in your life.” For participants who had difficulty naming close friends, it was explained that naming their “close” friends did not mean that they were necessarily close to these friends in an absolute sense, but that they were close to these friends relative to other acquaintances they might have. Of the 184 early adolescents who participated in the age 13 data collection, 181 of their close friends participated. The close friends selected at age 13 reported that they had known the adolescents for an average of 4.04 years (SD = 2.90). When asked “How close a friend would you say you are with the friend you are here with today?” from a scale of 1 (not a very close friend) to 5 (best friend), close friends reported that they were quite close to participants ( , SD = 0.75). No close friend selected a 1 and only one close friend selected a 2. All of the close friends selected at age 13 were required to be of the same sex as the participant. At ages 18 to 20, 164 of the target participants’ close friends participated. The close friends selected at age 18 reported that they had known the participants for an average of 6.9 years (SD = 3.55). Thirty-two (17.3%) of the friends chosen at age 18 were the same as those chosen at 13. Ten (6.10%) of the friends chosen at any point between ages of 18 and 20 were of the opposite sex from the participant. At age 24, 132 of the target participants’ close friends participated. The close friends selected at age 24 reported that they had known the participants for an average of 10.44 years (SD = 6.66). Seventy-three (39.5%) of the friends chosen at 24 were the same as those chosen at 18, and four (3%) were the same as those chosen at 13. Three (1.7%) participants nominated the same close friend at all three waves of data collection. Eleven (8.33%) of the friends chosen at age 24 were of the opposite sex from the participant.

At the age 18 and 24 assessments, participants in a romantic relationship of at least 3 months were invited to participate in filmed interaction tasks with their romantic partners. To maximize the number of romantic partners able to participate, dyads came in over a span of 3 years to complete observational and questionnaire measures. At the age 18 data collection, 70 (38%) of the original teens were in eligible romantic relationships and both they and their partners agreed to participate. Participants reported knowing their romantic partners an average of 1.22 years (SD = 1.13 years). At the age 24 data collection, 81 dyads (44% of the original sample) were eligible and agreed to participate. Participants reported knowing their romantic partners an average of 4.66 years (SD = 3.77 years). Two participants (2.86%) brought the same romantic partner to the age 18 and age 24 data collection. Same-sex couples were included in the sample; however, no same-sex couples participated in the age 18 data collection and only one same-sex couple participated in the age 24 data collection.

Of those 114 participants who did not participate at the age 18 romantic partner data collection, 75 (65.79%) did not meet the criteria of being in a relationship lasting at least 3 months. Of the 103 participants who did not participate in the age 24 romantic partner data collection, 57 (55.33%) did not meet the criteria of being in a relationship lasting at least 3 months. For the remainder in both cases, the majority of cases of non-participation were a result of partners’ declining our invitation to participate, and/or inability to schedule an observational assessment in which both parties were willing and able to participate. Analyses indicated that the target participants who did not participate at the age 18 romantic partner data collection had significantly higher scores on the measure of negative social expectations at age 13 (i.e., more negative expectations; , t = 2.41, p = .02). There were no other significant differences between those who did versus did not participate at the ages 18 or 24 romantic partner data collection on gender, family income, or initial levels of the variables measured.

To best address any potential biases due to attrition and missing data in longitudinal analyses, full information maximum likelihood methods were used, with analyses including all variables that were linked to future missing data (i.e., where data were not missing completely at random). Because these procedures have been found to yield less biased estimates than approaches (e.g., simple regression) that use listwise deletion of cases with missing data, the entire original sample of 184 for the larger study was utilized for these analyses. This analytic technique does not impute or create any new data nor does it artificially inflate significance levels. Rather, it simply takes into account distributional characteristics of data in the full sample so as to provide the least biased estimates of parameters obtained when some data are missing (Arbuckle, 1996). Alternative longitudinal analyses using just those adolescents without missing data (i.e., listwise deletion) yielded results that were substantively identical to those reported below.

Measures

Negative social expectations (age 13)

Adolescents’ social expectations were assessed at age 13 using the Children’s Expectations of Social Behavior Questionnaire (CESBQ; Rudolph, Hammen, & Burge, 1995). This measure consists of 15 hypothetical vignettes in which teens are asked to imagine themselves interacting with peers (e.g., “You’re working on a group project with some other kids at school and you make a suggestion for something that you could all do. What do you think they might say?” or “You’re feeling kind of upset about something that happened one morning at home and you decide to try to talk about it with a friend during lunch. As soon as the bell rings, you walk over to her and start to tell her about your problem. What do you think she might do?”). For each vignette, teens were asked to indicate whether they expected an accepting peer response (e.g., “They might try it out to see if it would work” or “She might listen to my problem and try to make me feel better,” scored 0), an indifferent response (e.g., “They might just pretend that I didn’t say anything and ignore my idea” or “She might just walk away and say that she wants to hang out with someone else,” scored 1), or a hostile response (e.g., “They might laugh and say that it was a pretty stupid idea” or “She might tell me that I always seemed to have problems and I should stop bothering her,” scored 2). The scores were then summed, with higher scores representing teens’ more negative expectations of peers’ behavior toward them. This measure has been used previously in studies of adolescents’ representations and peer relationships (Dykas et al., 2008; Garber & Kaminski, 2000; Gregory et al., 2007; Liu, 2008; Rudolph et al., 1997). Rudolph et al. (1995) report good internal consistency for the CESBQ (Cronbach’s α = .84) and the current study also had acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .75).

Observed hostile partner and participant behaviors (ages 18 and 24)

At age 18, participants and their romantic partners of at least 3 months duration participated in a revealed differences task in which they independently chose which character was right in hypothetical dating scenarios (e.g., “Jessica and David were at a party one night with their best friends who are also a couple. Later in the night they saw the guy making out with another girl. David wants to tell the guy’s girlfriend what they saw. Jessica doesn’t want to tell, she says it’s not any of their business, and they don’t know the whole story”). Partners then came together to reach a consensus on each scenario. At age 24, participants and romantic partners completed a revealed differences task in which they identified their biggest area of disagreement and were instructed to talk about the topic for 8 minutes. Common topics included moving in together, jealousy, money, chores, and jobs. Tasks were chosen to be developmentally appropriate (adolescent romantic partners may not have substantive areas of disagreement to discuss). Interactions at each wave were videotaped and then transcribed. The coding system employed yields ratings from 0 to 4 for each participant’s overall behavior toward his or her romantic partner in the interaction (Allen et al., 2000; Allen, Hauser, Bell, & O’Connor, 1994). Ratings are molar in nature, yielding overall scores for participants’ behaviors across the entire interaction; however, these molar scores are derived from an anchored coding system that considers both the frequency and intensity of each speech relevant to that behavior during the interaction in assigning the overall molar score. Interrater reliability was calculated for the overall scale using intraclass correlation coefficients and was in what is considered “good” range for this statistic (intraclass r = .70–.78; Cicchetti & Sparrow, 1981).

Specific interactive behaviors were considered, and used to derive an anchored overall code for the extent to which participants’ romantic partners employed hostile and overbearing conflict tactics with their partners—a scale that captures autonomy-undermining behaviors. The scale ranged from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating more hostile and overbearing behaviors from the romantic partner. The scale includes the following behaviors: (a) Overpersonalizing behaviors: Treating the disagreement as being in some respect a “fault” or feature of the person’s disagreeing rather than a difference in ideas and reasons. By not separating the person from the disagreement, it becomes difficult to discuss differences reasonably—who will give in becomes more important than exploring why a person took the position he or she took (intraclass r = .89 for romantic partners at age 18 to r = .78 for romantic partners at age 24). (b) Pressuring behaviors: The extent to which the individual proceeds in the discussion as though his or her main objective is to get his or her own selections accepted (rather than to listen to the other person and to come up with the best solution) and/or makes statements that implicitly or explicitly pressure in an effort to make the other person uncomfortable enough to change his or her mind (intraclass r = .65 for participants at age 18 to r = .90 for romantic partners at age 24). (c) Avoidance behaviors: The degree to which an individual steers away from disagreements or the chance to clarify disagreements. Behaviors indicative of avoidance include ceding the floor (as opposed to other person taking it) and being more interested in not disagreeing than in the outcome (intraclass r = .76 for participants at age 18 to r = .56 for participants at age 24). Correlations between the behavior codes and molar ratings ranged from r = .27, p = .02 (romantic partner avoidance at age 18) to r = .85, p = .001 (romantic partner pressuring at age 24).

Close friend and participant aggressive attitudes (ages 13, 18, and 24)

Close friend and participant reports of their own aggressive attitudes were assessed using the Aggressive Attitudes Questionnaire (Guerra, 1986; Slaby & Guerra, 1988). Close friends and participants rated how true each item was for them on a 5-point scale from really disagree to really agree. The 18-item scale captures the extent to which respondents endorse the necessity and acceptability of violence and aggression. Aggressive attitudes assessed by this and similar measures are associated with reports of actual aggressive behavior (Bosworth, Espelage, & Simon, 1999; Eliot & Cornell, 2009; Slaby & Guerra, 1988). Example items include “It’s OK to hit someone if you think he or she deserves it” and “Being raped must be awful” (reverse scored). Internal consistency for this measure was good (age 13 Cronbach’s α = .84, age 18 Cronbach’s α = .86, age 24 Cronbach’s α = .82).

Results

Primary Analyses

Table 1 displays means, standard deviations, and correlations for the variables used in the study.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Intercorrelations of Substantive Variables.

|

|

SD | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Negative social expectations (13) | 3.36 | 3.72 | .25 *** | .10 | .07 | .35*** | 20** | .28*** | .03 | −.01 | .24** | .33*** | −.20** | −.22** | |

| 2. | Participant aggressive attitudes (13) | 36.11 | 9.24 | — | .18* | .16 | .24* | .54*** | .31*** | .22* | .07 | .42*** | .17* | −.28*** | −.23** | |

| 3. | Close friend aggressive attitudes (13) | 36.35 | 8.98 | — | .09 | .28* | .21** | .28*** | .15 | .24* | .22** | .23** | −.30*** | −.21** | ||

| 4. | Observed participant partner hostility (18) | 1.20 | 0.57 | — | .47*** | .23 | .16 | −.01 | .22 | −.08 | .20 | −.11 | .19 | |||

| 5. | Observed romantic partner hostility (18) | 1.10 | 0.52 | — | .36** | .32** | −.19 | −.05 | .18 | .30* | −.18 | −.08 | ||||

| 6. | Participant aggressive attitudes (18) | 30.26 | 8.73 | — | .47*** | .25* | .21 | .63*** | .16 | −.19** | −.33*** | |||||

| 7. | Close friend aggressive attitudes (18) | 29.11 | 8.13 | — | .18 | .11 | .37*** | .45*** | −.16* | −.33*** | ||||||

| 8. | Observed participant hostility (24) | 0.60 | 0.53 | — | .69*** | .18 | .20 | −.36*** | .05 | |||||||

| 9. | Observed romantic partner hostility (24) | 0.55 | 0.52 | — | .09 | .28* | −.22* | .11 | ||||||||

| 10. | Participant aggressive attitudes (24) | 28.40 | 9.36 | — | .25** | −.17* | −.36*** | |||||||||

| 11. | Close friend aggressive attitudes (24) | 29.11 | 8.13 | — | −.17* | −.24** | ||||||||||

| 12. | Participant gender (1 = male, 2 = female) | — | — | — | −.11 | |||||||||||

| 13. | Family income | 43,600 | 22,400 | — |

p < .05.

p ≤.01.

p ≤ .001.

Model identification

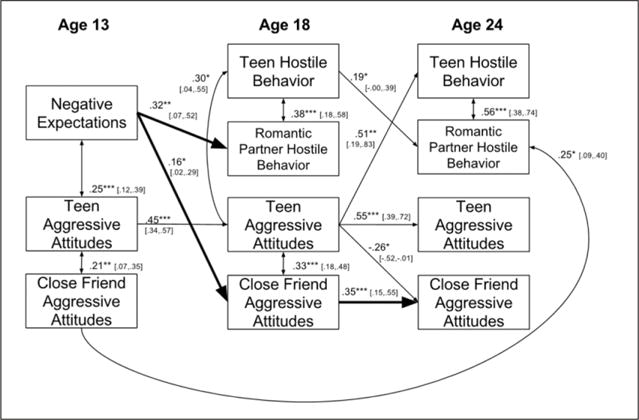

Hypotheses were tested in Mplus (Version 7.2; Muthén & Muthén, 2015). A fully saturated path model using bootstrapped confidence intervals was examined using early adolescent negative expectations to predict participant and friend-reported aggressive attitudes in late adolescence and early adulthood, as well as observed participant and romantic partner hostility in late adolescence and early adulthood (Figure 1). Participant gender and family income were included as covariates, along with age 13 levels of participant and friend-reported aggressive attitudes.

Figure 1.

Fully saturated model from negative social expectations at age 13 to observed romantic partner and participant hostility and close friend-reported aggressive attitudes in late adolescence and early adulthood.

Note. Model controls for participant gender and family income. Only significant paths depicted. Bold lines represent primary study hypotheses.

*p ≤ .05. **p ≤ .01. ***p ≤ .001.

As shown in the first half of Figure 1, results supported the first hypothesis: More negative expectations in early adolescence were associated with higher observed romantic partner hostility (β = .32, p = .01) and friend-reported hostile attitudes (β = .16, p = .02) in late adolescence. Early adolescents with more negative expectations were more likely to have late adolescent partners who reported and displayed more hostility, after accounting for age 13 friend aggressive attitudes, participants’ own aggressive attitudes at age 13 and 18, participants’ own observed hostility with romantic partners at age 18, and demographic factors.

As shown in the second half of Figure 1, results partially supported the second hypothesis: Friend-reported aggressive attitudes at age 18 predicted higher friend-reported aggressive attitudes at age 24 (β = .35, p = .001), after accounting for age 13 friend aggressive attitudes, participants’ own aggressive attitudes at ages 13, 18, and 24, participant and romantic partner observed hostility at ages 18 and 24, and demographic factors. Early adolescent negative expectations did not, in adulthood, directly predict aggressive attitudes in friends or observed hostility in romantic partners. No significant indirect effects were found.

An unexpected finding of note was that close friend aggressive attitudes at age 13 predicted age 24 observable romantic partner hostility, above and beyond all other measures in the model (β = .25, p = .04), suggesting that having close friends who endorse aggressive attitudes in early adolescence was predictive of higher levels of romantic partner hostility in adulthood.

Discussion

This study provided support for the hypothesis that the expectations that adolescents bring into new relationships could be one factor that may account for the tendency of some individuals to repeatedly become involved in hostile and harmful relationships. Thirteen-year-olds with more negative expectations of peers were found to be more likely to become involved with observably hostile romantic partners and with friends who reported hostile attitudes by age 18. The presence of friends with hostile attitudes in late adolescence in turn predicted the presence of friends with hostile attitudes in early adulthood. The presence of friends with hostile attitudes in early adolescence predicted hostility observed from romantic partners in adulthood. Together, these results suggest a degree of continuity from expectations to hostility in important relationships as well as from different types of hostile relationships. The longitudinal (11-year) scope of this study suggests that adolescent social expectations even as early as age 13, may have truly enduring implications.

Negative Social Expectations

These findings are consistent with several predictions from previous research and theory related to social expectations: Attachment theory suggests that people develop “internal working models” of relationships and then tend to act in ways that follow the expected roles for both themselves and their partners (N. L. Collins & Read, 1994). Similarly, work on hostile attribution biases suggests that people behave in accordance with negative expectations and thus elicit the expected negative reaction from others, which then confirms their expectation (Dodge et al., 2003). It is of note that, in the current study, participants with more negative expectations at 13 were less likely to be in a significant romantic relationship by age 18. Although the exact explanation for this finding is unclear, it may be that adolescents with negative expectations are less likely to seek out romantic relationships earlier on, or may elicit more rejection from current or potential partners. Those high in rejection sensitivity have also been shown to be more likely to behave in ways that elicit the expected rejection from partners in the short term, again confirming their expectation (Downey & Feldman, 1996). The most likely mechanism for explaining this pattern is that adolescents with negative expectations of peers select for and/or tolerate hostility from others because they perceive it as normal or even inevitable—and the more hostile partners they have over development, the more their expectations may be confirmed and reinforced.

Hostile Relationships

Hostile relationships are associated with a variety of physical, emotional, and social difficulties. Romantic relationships characterized by hostility have been linked to poorer physical and mental health functioning across a variety of dimensions (Bertera, 2005; Cranford, 2004; Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001; Linder et al., 2002; Miller et al., 1996). Friendships are central in adolescence, and close friendships serve attachment functions for many individuals into adulthood (Markiewicz et al., 2006). Hostile close friends may normalize and/or encourage the acceptance of aggression and continue to sustain individuals’ negative expectations of relationships going forward (Freeman, Hadwin, & Halligan, 2011; King & Terrance, 2008; Pittman & Richmond, 2008). Thus, identifying early predictors of the formation of relationships with hostile and conflictual individuals could ultimately be useful in targeting and directing efforts to prevent serious difficulties as adolescents develop. In addition, if these findings are replicated in further research, they might suggest that cognitive interventions in early adolescence, even in a non-clinically referred population, could be beneficial in preventing individuals’ progression through a harmful social trajectory. Adolescence is a time of greater flexibility for changing thoughts and behaviors than adulthood (Crone & Dahl, 2012). Negative expectations, however they are formed, may be both more malleable and more easily identified early in adolescence than an established behavioral pattern of selecting hostile partners, and so these expectations could provide an important entry point for interventions. To eliminate the possibility that participants simply perceived others as more hostile through time, this study used observed romantic partner behaviors and close friend reports of the close friend’s attitudes. Furthermore, to control for the possibility that participants were merely eliciting reciprocated hostility, participants’ hostile behaviors and attitudes were included in analyses. In addition, reducing the possibility of participant influence as an explanation for partners’ hostility, the majority of participants selected new partners over time: Only three participants nominated the same friend at all three waves of data collection, and only two participants had the same romantic partner from the age 18 to age 24 waves of data collection.

Limitations and Future Directions

No association was found between negative expectations and age 24 observable romantic partner hostility. There are several possible explanations: The dynamic of romantic relationships changes substantially between late adolescence and early adulthood—with relationships tending to become more intimate and less volatile (Connolly & McIsaac, 2011; Furman, Brown, & Feiring, 1999). In the current study, the average amount of observed hostility at age 24 was half of that observed at age 18 . Perhaps this reflects a true decline in overall hostility; alternatively, hostility may manifest differently in adult relationships versus adolescent relationships, or perhaps the effects simply are not stable over such a long (11-year) time period. In addition, the number of romantic partner dyads available for analysis at both waves was relatively small. Although the number of dyads (70 at age 18 and 81 at age 24) is typical for observational studies of romantic partners (Ha, Dishion, Overbeek, Burk, & Engels, 2014; Madsen & Collins, 2011), it may contribute to the lack of consistency in effects. Future research can examine whether and how early adolescent negative expectations influence other facets of adult romantic relationships beyond observed hostility.

The measure of negative expectations used in this study was designed for children and so it was not possible to re-administer it to late adolescent and adult participants. Therefore, we are unable to assess how negative expectations may develop and relate to outcomes at later time points in the current study. Future work should incorporate measures of negative expectations appropriate for older participants to better capture these associations through time. Another limitation of this study is the lack of data prior to age 13. Without earlier data, it is impossible to pinpoint the origin of participants’ negative expectations for others; however, it is reasonable to theorize that they may come from some combination of negative family experiences (Baldwin, 1992; Main, Kaplan, & Cassidy, 1985), negative peer experiences (London, Downey, Bonica, & Paltin, 2007), or child characteristics such as temperament (Rothbart & Ahadi, 1994; Sanson, Hemphill, & Smart, 2004). It is also possible that both the negative social expectations and the tendency to select hostile partners observed in this study may follow from some earlier experience, such as childhood maltreatment. While negative expectations of others seem to play a clear role in the chain of events leading to hostile partner selection, more research from earlier in childhood is needed to determine the origin of these negative expectations.

Because romantic partner reports of their own aggressive attitudes and observations of adult friend hostility were not available in the current sample, we are unable to generalize one type of partner hostility to the other type (i.e., observed hostility is likely different than self-reported aggressive attitudes). Future research should also incorporate use of observational data of adult friends and the self-reported aggressive attitudes of romantic partners to determine if friends and romantic partners show similar patterns of hostility across these measures. Friendships in adulthood tend to be less intense than romantic relationships (Carbery & Buhrmester, 1998), so the same level of hostility may not be seen in observations of interactions with friends as was found with romantic partners. On the other hand, adults may be more willing to tolerate hostility in friendships because they are often not as central to their lives as romantic relationships. It is also important to note that, while most participants selected different close friends at each wave, participants’ friends reported knowing the participants for an average of more than 10 years by age 24. Although this study accounts for close friend aggressive attitudes in early adolescence, it is still possible that adolescents with negative expectations are more likely to maintain and strengthen long-term relationships with hostile individuals, rather than to continually select new hostile partners over time. However, the resulting negative effects of these relationships would remain—and in fact, may be even more harmful if individuals are associating with hostile friends over long periods of time. The less intense yet long-lasting nature of many adult friendships may explain why there was less apparent continuity in observable romantic partner hostility than in close friend aggressive attitudes. As individuals develop, they may not select for and/or accept overt hostility from romantic partners, yet may still keep or select friends with hostile attitudes, which may reflect an ongoing expectation that such attitudes are normal or unavoidable. More studies are needed to determine why individuals may associate with friends who endorse hostile attitudes over time.

Future research should also further examine the hypothesis that individuals with negative expectations are selecting hostile partners over time and not influencing hostile behavior development in others. Age 13 participant negative expectations did not predict later participant hostility and negative expectations predicted partner hostility above and beyond concurrent participant hostility. These results suggest that partner hostility is not simply due to participant hostility or participants evoking hostility in partners (although they do suggest that late adolescents who display higher levels of hostility are more likely to have partners who also display higher levels of hostility). The lack of continuity between expectations and participant hostility over time notably strengthens the idea of partner selection over participant influence. Perhaps individuals who generally expect and/or accept negativity from others are less likely to become hostile themselves than those who expect better treatment. However, more research is needed to address this issue. Although this study controlled for participant hostility and used a measure of close friend aggressive attitudes (which tend to be relatively stable), it is still possible that some other behavior on the part of participants is contributing to hostility from others. In addition, future research should incorporate measures of partner expectations to better disentangle selection from influence in terms of both cognitions and behaviors.

Conclusion

Understanding the roots of hostility and hostile relationships—which have been found to be so detrimental for physical and mental health—is crucial to identifying intervention points to address the development of hostile relationships. This, and future research targeting early cognitive roots of hostile relationships, may provide an ideal entry point for intervention as research suggests that adolescent cognitions are more malleable than later, engrained patterns of behavior and hostile partner selection.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Research reported in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development and the National Institutes of Health (Award Nos. R01HD058305 and R01-MH58066).

Biographies

Emily L. Loeb is a fifth-year graduate student in clinical psychology at the University of Virginia. Her particular research interests include adolescents’ social expectations and how they relate to peer and romantic relationship development. She is also interested in research with marginalized adolescent populations.

Joseph S. Tan is a fourth-year graduate student in clinical psychology at the University of Virginia. His research interests include adolescent romantic relationship processes, attachment, and quantitative modeling. He is also pursuing work with underrepresented college students.

Elenda T. Hessel is a sixth-year graduate student in clinical psychology at the University of Virginia, currently completing her clinical internship. Her research interests include emotion regulation, adolescent friendships, and romantic relationship development. She is also interested in the neuro correlates of emotion regulation.

Joseph P. Allen is a faculty member at the University of Virginia. He has published extensively on the topics of adolescent development, attachment, peer influence, romantic relationships, and other topics related to adolescence and young adulthood. His current interests include the relationship between social connection and physical health.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health Program.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Alexander PC. Childhood trauma, attachment, and abuse by multiple partners. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2009;1:78–88. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Hauser ST, Bell KL, Boykin KA, Tate DC. Autonomy and relatedness coding system manual (Version 2.0) Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia; 1994. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Hauser ST, Bell KL, O’Connor TG. Longitudinal assessment of autonomy and relatedness in adolescent-family interactions as predictors of adolescent ego development and self-esteem. Child Development. 1994;65:179–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Land D. Attachment in adolescence. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment theory and research and clinical applications. New York, NY: Guilford; 1999. pp. 319–335. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In: Marcoulides GA, Schumacker RE, editors. Advanced structural equation modeling. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Arriaga XB, Foshee VA. Adolescent dating violence: Do adolescents follow in their friends’, or their parents’, footsteps? Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2004;19:162–184. doi: 10.1177/0886260503260247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin MW. Relational schemas and the processing of social information. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:461–484. [Google Scholar]

- Bertera EM. Mental health in US adults: The role of positive social support and social negativity in personal relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2005;22:33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bosworth K, Espelage DL, Simon TR. Factors associated with bullying behavior in middle school students. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 1999;19:341–362. [Google Scholar]

- Bowker JC, Fredstrom BK, Rubin KH, Rose-Krasnor L, Booth-LaForce C, Laursen B. Distinguishing children who form new best-friendships from those who do not. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2010;27:707–725. doi: 10.1177/0265407510373259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbery J, Buhrmester D. Friendship and need fulfillment during three phases of young adulthood. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1998;15:393–409. [Google Scholar]

- Carbone-Lopez K, Rennison CM, Macmillan R. The transcendence of violence across relationships: New methods for understanding men’s and women’s experiences of intimate partner violence across the life course. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2012;28:319–346. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Bem DJ, Elder GH. Continuities and consequences of interactional styles across the life course. Journal of Personality. 1989;57:375–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1989.tb00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Elder GH, Bem DJ. Moving away from the world: Life-course patterns of shy children. Developmental Psychology. 1988;24:824–831. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J. Adult romantic attachments: A developmental perspective on individual differences. Review of General Psychology. 2000;4:111–131. [Google Scholar]

- Chango JM, McElhaney K, Allen JP, Schad MM, Marston E. Relational stressors and depressive symptoms in late adolescence: Rejection sensitivity as a vulnerability. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2012;40:369–379. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9570-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti DV, Sparrow SA. Developing criteria for establishing interrater reliability of specific items: Applications to assessment of adaptive behavior. American Journal of Mental Deficiency. 1981;86:127–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins L, Read SJ. Cognitive representations of attachment: The structure and function of working models. In: Bartholomew K, Perlman D, editors. Attachment processes in adulthood. London, England: Jessica Kingsley; 1994. pp. 53–90. [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA. Relationships and development during adolescence: Interpersonal adaptation to individual change. Personal Relationships. 1997;4:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly J, Mclsaac C. Romantic relationships in adolescence. In: Underwood MK, Rosen LH, editors. Social development: Relationships in infancy, childhood, and adolescence. New York: The Gilford Press; 2011. pp. 180–203. [Google Scholar]

- Cranford JA. Stress-buffering or stress-exacerbation? Social support and social undermining as moderators of the relationship between perceived stress and depressive symptoms among married people. Personal Relationships. 2004;11:23–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2004.00069.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creasey G, Kershaw K, Boston A. Conflict management with friends and romantic partners: The role of attachment and negative mood regulation expectancies. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1999;28:523–543. [Google Scholar]

- Crone EA, Dahl RE. Understanding adolescence as a period of social-affective engagement and goal flexibility. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2012;13:636–650. doi: 10.1038/nrn3313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui M, Ueno K, Gordon M, Fincham FD. The continuation of intimate partner violence from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2013;75:300–313. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinero RE, Conger RD, Shaver PR, Widaman KF, Larsen-Rife D. Influence of family of origin and adult romantic partners on romantic attachment security. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:622–632. doi: 10.1037/a0012506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Lansford JE, Burks VS, Bates JE, Pettit GS, Fontaine R, Price JM. Peer rejection and social information-processing factors in the development of aggressive behavior problems in children. Child Development. 2003;74:374–393. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.7402004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Feldman SI. Implications of rejection sensitivity for intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:1327–1343. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.6.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Freitas AL, Michaelis B, Khouri H. The self-fulfilling prophecy in close relationships: Rejection sensitivity and rejection by romantic partners. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:545–560. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.2.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykas MJ, Ziv Y, Cassidy J. Attachment and peer relations in adolescence. Attachment & Human Development. 2008;10:123–141. doi: 10.1080/14616730802113679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliot M, Cornell DG. Bullying in middle school as a function of insecure attachment and aggressive attitudes. School Psychology International. 2009;30:201–214. [Google Scholar]

- Feeney BC, Cassidy J, Ramos-Marcuse F. The generalization of attachment representations to new social situations: Predicting behavior during initial interactions with strangers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;95:1481–1498. doi: 10.1037/a0012635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman K, Hadwin JA, Halligan SL. An experimental investigation of peer influences on adolescent hostile attributions. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2011;40:897–903. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.614582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Brown BB, Feiring C, editors. The development of romantic relationships in adolescence. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Garber J, Kaminski KM. Laboratory and performance-based measures of depression in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2000;29:509–525. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP2904_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein SE. Relational aggression in young adults’ friendships and romantic relationships. Personal Relationships. 2011;18:645–656. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory AM, Rijsdijk FV, Lau JY, Napolitano M, McGuffin P, Eley TC. Genetic and environmental influences on interpersonal cognitions and associations with depressive symptoms in 8-year-old twins. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:762–775. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.4.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra N. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Harvard University; Boston, MA: 1986. The assessment and training of interpersonal problem-solving skills in aggressive and delinquent youth. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero LK. Nonverbal involvement across interactions with same-sex friends, opposite-sex friends and romantic partners: Consistency or change? Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1997;14:31–58. [Google Scholar]

- Güroğlu B, Cillessen AHN, Haselager GJT, van Lieshout CFM. “Tell me who your friends are and I’ll tell you who your friends will be”: Consistency and change in social competence in adolescent friendships across school transitions. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2012;29:861–883. [Google Scholar]

- Ha T, Dishion TJ, Overbeek G, Burk WJ, Engels RC. The blues of adolescent romance: Observed affective interactions in adolescent romantic relationships associated with depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2014;42:551–562. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9808-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafen CA, Spilker A, Chango J, Marston EG, Allen JP. To accept or reject? The impact of adolescent rejection sensitivity on early adult romantic relationships. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2014;24:55–64. doi: 10.1111/jora.12081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser J, Newton TL. Marriage and health: His and hers. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:472–503. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.4.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AR, Terrance C. Best friendship qualities and mental health symptomatology among young adults. Journal of Adult Development. 2008;15:25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Linder JR, Collins WA. Parent and peer predictors of physical aggression and conflict management in romantic relationships in early adulthood. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:252–262. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder JR, Crick NR, Collins WA. Relational aggression and victimization in young adults’ romantic relationships: Associations with perceptions of parent, peer, and romantic relationship quality. Social Development. 2002;11:69–86. [Google Scholar]

- Liu YL. An examination of three models of the relationships between parental attachments and adolescents’ social functioning and depressive symptoms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2008;37:941–952. [Google Scholar]

- London B, Downey G, Bonica C, Paltin I. Social causes and consequences of rejection sensitivity. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2007;17:481–506. [Google Scholar]

- Luecken LJ, Roubinov DS. Hostile behavior links negative childhood family relationships to heart rate reactivity and recovery in young adulthood. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2012;84:172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen SD, Collins WA. The salience of adolescent romantic experiences for romantic relationship qualities in young adulthood. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21:789–801. [Google Scholar]

- Main M, Kaplan N, Cassidy J. Security in infancy, childhood, and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1985;50(1–2):66–104. [Google Scholar]

- Markiewicz D, Lawford H, Doyle AB, Haggart N. Developmental differences in adolescents’ and young adults’ use of mothers, fathers, best friends, and romantic partners to fulfill attachment needs. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35:121–134. [Google Scholar]

- Marston EG, Hare A, Allen JP. Rejection sensitivity in late adolescence: Social and emotional sequelae. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2010;20:959–982. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00675.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merton RK. The self-fulfilling prophecy. The Antioch Review. 1948;8:193–210. [Google Scholar]

- Miller TQ, Smith TW, Turner CW, Guijarro ML, Hallet AJ. Meta-analytic review of research on hostility and physical health. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;119:322–348. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.119.2.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Muthén L. Mplus Version 7.2 [Computer software] Los Angeles, CA: Author; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pittman LD, Richmond A. University belonging, friendship quality, and psychological adjustment during the transition to college. Journal of Experimental Education. 2008;76:343–362. [Google Scholar]

- Purdie V, Downey G. Rejection sensitivity and adolescent girls’ vulnerability to relationship-centered difficulties. Child Maltreatment. 2000;5:338–349. doi: 10.1177/1077559500005004005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA. Temperament and the development of personality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103(1):55–66. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Hammen C, Burge D. Cognitive representations of self, family, and peers in school-age children: Links with social competence and sociometric status. Child Development. 1995;66:1385–1402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Hammen C, Burge D. A cognitive-interpersonal approach to depressive symptoms in preadolescent children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1997;25:33–45. doi: 10.1023/a:1025755307508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanson A, Hemphill SA, Smart D. Connections between temperament and social development: A review. Social Development. 2004;13:142–170. [Google Scholar]

- Slaby R, Guerra N. Cognitive mediators of aggression in adolescent offenders: 1. Assessment. Developmental Psychology. 1988;24:580–588. [Google Scholar]

- Stocker CM, Richmond MK. Longitudinal associations between hostility in adolescents’ family relationships and friendships and hostility in their romantic relationships. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:490–497. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.3.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss C, Morry MM, Kito M. Attachment styles and relationship quality: Actual, perceived, and ideal partner matching. Personal Relationships. 2012;19:14–36. [Google Scholar]

- Vitaro F, Brendgen M, Tremblay RE. Reactively and proactively aggressive children: Antecedent and subsequent characteristics. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;43:495–505. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]