Abstract

Objective

This study evaluated genetic associations of APOE alleles with risk of MSA and α-synuclein pathology, and also examined whether apoE isoforms differentially affect α-synuclein uptake in oligodendrocytes cell.

Methods

168 pathologically-confirmed MSA patients, 89 clinically-diagnosed MSA patients, and 1277 control subjects were genotyped for APOE. Human oligodendrocyte cell lines were incubated with α-synuclein and recombinant human apoE, with internalized α-synuclein imaged by confocal microscopy and cells analyzed by flow cytometry.

Results

No significant association with risk of MSA or was observed for either APOE ε2 or ε4. α-synuclein burden was also not associated with APOE alleles in the pathologically-confirmed patients. Interestingly, in our cell assays, apoE ε4 significantly reduced α-synuclein uptake in the oligodendrocytic cell line.

Conclusions

Despite differential effects of apoE isoforms on α-synuclein uptake in a human oligodendrocytic cell, we did not observe a significant association at the APOE locus with risk of MSA or α-synuclein pathology.

Keywords: Multiple system atrophy, apolipoprotein E, genetics, protection, oligodendrocyte (max 5)

Introduction

Widespread presence of glial cytoplasmic inclusions (GCIs) is the neuropathologic hallmark of MSA.1 GCI is the accumulation of α-synuclein protein in the cytoplasm of oligodendrocytes, the myelin-producing support cells in CNS. Recently, dysregulation of the specialized lipid metabolism involved in myelin synthesis and maintenance by oligodendrocytes has been associated with the unique neuropathology of MSA.2 Apolipoprotein E (APOE) is a well-established lipid-metabolism gene. The APOE ε4 allele is the major genetic determinant of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (AD) risk and has also been strongly associated the synucleinopathy dementia with Lewy bodies3, whereas APOE ε2 is known as a protective factor for AD and dementia.3 Compared to other more common neurodegenerative diseases, little is known about the genetics of MSA; recent reports have nominated variants in several genes (SNCA, MAPT, LRRK2, COQ2, GBA) as potential risk factors, though validation is needed.4 We hypothesized that the APOE alleles could play a role in the pathogenesis of MSA. In this study, we first assessed associations of the APOE ε4 and ε2 alleles with risk of MSA and with α-synuclein burden. We also investigated whether apolipoprotein E (apoE) differentially affected α-synuclein uptake in a human oligodendrocytic cell line in an isoform-dependent manner.

Methods

Study subjects

168 pathologically-confirmed MSA patients5, 89 clinically-diagnosed MSA patients1, and 1277 controls were included (Supplemental Table 1). The pathologically-confirmed patients were all available cases obtained from the Mayo Clinic brain bank for neurodegenerative disorders in Jacksonville, FL, and were diagnosed by a single neuropathologist (D.W.D.).5 Both clinically-diagnosed MSA patients and control subjects were seen at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, FL (MSA: N=54, Controls: N=712) and Rochester, MN (MSA: N=35, Controls: N=565). All controls were neurologically normal and free of a family history of a movement disorder. All subjects were unrelated non-Hispanic Caucasians. The primary comparison was between the pathologically-confirmed MSA patients and controls. As a secondary comparison, we combined the pathologically-confirmed and clinically-diagnosed MSA patients for comparison with controls.

Pathological analysis

Immunohistochemistry for α-synuclein (NACP, Mayo Clinic antibody, Jacksonville, FL)6 was conducted to establish the neuropathological diagnosis.5 The burden of α-synuclein in striatopallidal fibers was measured quantitatively as described previously and was available for 130 of the pathologically-confirmed MSA patients.7 Braak neurofibrillary tangles stage (available for 163 patients) and Thal amyloid phase (available for 158 patients) were assigned to each case with thioflavin S fluorescent microscopy.8, 9

Genetic Analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood monocytes or frozen brain tissue using the standard protocols. Genotyping for APOE alleles (rs429358 C/T and rs7412 C/T) was performed using a custom TaqMan Allelic Discrimination Assay on an ABI 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) (primer sequences are available upon request).

Statistical analysis

Associations of presence of the APOE ε4 and ε2 alleles with risk of MSA were evaluated using logistic regression models that were adjusted for age and gender. Additionally, we also compared the ε3/ε3 genotype to the ε3/ε4 genotype to directly assess the effect of ε4, and similarly we compared the ε3/ε3 genotype to the ε2/ε3 genotype to directly assess the effect of ε2. Finally, we utilized Fisher’s exact test to perform a general comparison of APOE genotype.

In pathologically-confirmed MSA patients, we assessed associations of ε4 and ε2 with α-synuclein burden in striatopallidal fibers, Braak stage, and Thal phase using linear regression and proportional odds logistic regression models that were adjusted for age at death and gender. Given that statistical tests of association were performed for both APOE ε4 and ε2, P≤0.025 was considered as statistically significant after Bonferroni correction. With 168 pathologically-confirmed MSA patients and 1269 controls included in our primary analysis, we had 80% power at the P≤0.025 significance level to detect odds ratios of 1.75 (association with ε4) and 1.90 (association with ε2) in relation to risk of MSA. All statistical analysis was performed using SAS.

Materials

Human oligodendrocytic cell line, MO3.13, was purchased from Cedarlane Labs (Burlington, NC). Recombinant human α-synuclein, HiLyte™ Fluor 488 labeled was from Anaspec (Fremont, CA). Recombinant human apoE proteins were from Fitzgerald Industries (Acton, MA).

Flow cytometry analysis of α-Synuclein uptake

Human oligodendrocytic cell line, MO3.13, were cultured and treated with 10 nM of fluorescently labeled recombinant human α-synuclein with or without 50 nM of recombinant human apoE for 18 hours. Total of 10,000 cells were analyzed by FACS Accuri (BD Bioscience). The median fluorescence signals in each condition were quantified using CFLOW® plus software (BD Bioscience), and analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc analysis.

Confocal analysis of α-Synuclein uptake by MO3.13

MO3.13 were plated on coverslips and treated with 250 nM α-synuclein HiLyte 488 and 1.25 μM of apoE for 18 hours. At the end of the treatment, LysoTracker® Red (Life Technologies) was added to label lysosomes. The images were acquired using confocal laser-scanning fluorescence microscope (LSM 510, Carl Zeiss).

Results

There was no significant association of APOE ε4 or ε2 with risk of MSA (Table 1) or risk of MSA subtypes (Supplemental Tables 2 and 3). Similarly, when making a general comparison of APOE genotype with controls, no difference was observed for the pathologically-confirmed MSA patients (P=0.78) or the combined MSA series (P=0.47) (Supplemental Table 4). There was no association between α-synuclein burden in the striatopallidal fibers and presence of either APOE ε4 (P=0.71) or ε2 (P=0.49). As shown in Supplemental Table 5, in the pathologically-confirmed MSA series, ε4 was associated with a significantly higher Thal phase (P<0.0001) but was not associated with Braak stage (P=0.25), while ε2 was not associated with either outcome after multiple testing adjustment (P≥0.047) though non-significant trends toward less AD pathology in ε2 carriers were noted.

TABLE 1.

Associations of APOE ε4 and ε2 with risk of MSA

| Association between APOE ε4 and risk of MSA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Comparison/Disease group | N | No. (%) with APOE ε4 | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

| Presence vs. absence of APOE ε4 | ||||

| Controls | 1269 | 318 (25.1%) | 1.00 (reference) | N/A |

| Pathologically-confirmed MSA patients | 168 | 37 (22.0%) | 0.79 (0.53, 1.17) | 0.24 |

| All MSA patients (pathologically-confirmed and clinically-diagnosed) | 257 | 57 (22.2%) | 0.78 (0.56, 1.08) | 0.13 |

| Comparison of ε3/ε3 and ε3/ε41 | ||||

| Controls | 1044 | 260 (24.9%) | 1.00 (reference) | N/A |

| Pathologically-confirmed MSA patients | 138 | 33 (23.9%) | 0.90 (0.59, 1.36) | 0.61 |

| All MSA patients (pathologically-confirmed and clinically-diagnosed) | 214 | 51 (23.8%) | 0.86 (0.61, 1.23) | 0.42 |

|

| ||||

| Association between APOE ε2 and risk of MSA | ||||

|

| ||||

| Comparison/Disease group | N | No. (%) with APOE ε2 | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|

| ||||

| Presence vs. absence of APOE ε2 | ||||

| Controls | 1269 | 200 (15.8%) | 1.00 (reference) | N/A |

| Pathologically-confirmed MSA patients | 168 | 29 (17.3%) | 1.13 (0.73, 1.73) | 0.59 |

| All MSA patients (pathologically-confirmed and clinically-diagnosed) | 257 | 42 (16.3%) | 1.07 (0.74, 1.54) | 0.73 |

| Comparison of ε 3/ε3 and ε2/ε32 | ||||

| Controls | 948 | 164 (17.3%) | 1.00 (reference) | N/A |

| Pathologically confirmed MSA patients | 131 | 26 (19.8%) | 1.18 (0.74, 1.87) | 0.50 |

| All MSA patients (pathologically-confirmed and clinically-diagnosed) | 199 | 36 (18.1%) | 1.06 (0.71, 1.59) | 0.77 |

OR=odds ratio; CI=confidence interval. ORs, 95% CIs, and p-values result from logistic regression models adjusted for age (age at death for pathologically-confirmed MSA patients, age at MSA onset for clinically-diagnosed MSA patients, and age at blood draw for controls) and gender.

For comparison of the ε3/ε3 and ε3/ε4 genotypes, ORs correspond to the ε3/ε4 genotype, and individuals with APOE genotypes other than ε3/ε3 or ε3/ε4 (i.e. ε2/ε2, ε2/ε3, ε2/ε4, and ε4/ε4) were excluded.

For comparison of the ε3/ε3 and ε2/ε3 genotypes, ORs correspond to the ε2/ε3 genotype, and individuals with APOE genotypes other than ε3/ε3 or ε2/ε3 (i.e. ε2/ε2, ε2/ε4, ε3/ε4, and ε4/ε4) were excluded.

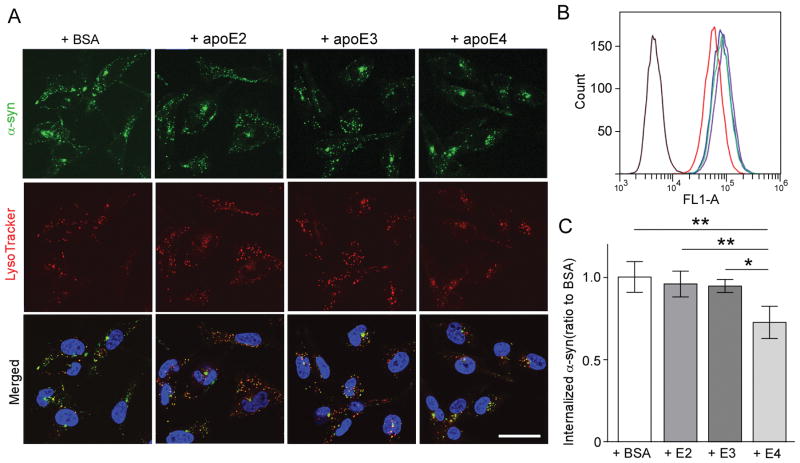

In our cellular assay, the human oligodendrocytic cell line, MO3.13, showed reduced colocalization of fluorescently-labeled α-synuclein and lysoTracker when co-treated with recombinant apoE ε4 compared to apoE ε2, ε3, or bovine serum albumin (Fig. 1A). The flow cytometry analysis further confirmed the significantly reduced internalization of fluorescently-labeled α-synuclein by MO3.13 when co-treated with apoE ε4 (Fig. 1B and 1C).

Figure 1. ApoE4 reduces α-Synuclein uptake by oligodendrocytic cell line.

(A) Confocal analysis of α-Synuclein (green) internalization by MO3.13 co-treated with apoE or BSA. Blue: DAPI, red: LysoTracker®. Scale bar= 20 μm. (B) Flow cytometry analysis of MO3.13 incubated with α-Synuclein and apoE (E2: green, E3: blue, E4: red) or BSA (purple). (C) The median fluorescence signals in each condition. Data plotted as mean ± SD (N= 4, One-Way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc analysis, * p< 0.05, ** p< 0.01).

Discussion

The results of our genetic study showed that neither the APOE ε4 nor ε2 alleles were notably associated with risk of MSA. These findings are in line with the results of previous small studies (n= 22; 59; 47; 40 and 12)10–14 and no signal at the APOE locus in the recent genome-wide association study of 331 pathologically-confirmed MSA patients.15 It also is worth noting that in agreement with these findings, a recent study reported no association between rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder (which could be a clinical prodromal feature preceding the development of MSA) and risk of MSA.16

Interestingly, in our oligodendrocytic cellular assays, we showed that the apoE ε4 isoform significantly reduced α-synuclein uptake, which means apoE regulates α-synuclein uptake in an isoform-dependent manner. The mechanisms underlying this observation remains to be investigated. Notably, oligodendrocytes have little endogenous α-synuclein,17 nevertheless GCIs (the pathological hallmark of MSA) consist of α-synuclein. One possible mechanism is that oligodendrocytes might take up α-synuclein from the extracellular environment to make GCIs in the brain of MSA.17 Based on our results, we could hypothesize that apoE ε4 may be a disease progression modifier for MSA by reducing the uptake of α-synuclein by oligodendrocytes. Although the lack of association between ε4 and risk of MSA in our genetic association analysis does not initially seem to support this result, it is important to highlight that although not statistically significant, the direction of the association that we observed was protective (OR=0.78), and based on 95% confidence limits this could plausibly be as low as 0.56; the possibility of a false-negative association is important to consider. Given our functional data, further studies may be warranted to investigate whether APOE allelic variation plays a role in MSA susceptibility or progression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding agencies: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

The authors thank those who contributed to their research, particularly the patients and families who donated DNA samples and brain tissue for this work. The Mayo Clinic Jacksonville is a Morris K. Udall Parkinson’s Disease Research Center of Excellence (NINDS P50 NS072187). This work is also supported by NINDS R01 NS078086 (OAR), P01 NS44233 (PAL), U54 NS065736 (PAL), K23 NS075141(WS), UL1 RR24150 (PAL), R01 NS092625 (PAL), R01 FD478 (PAL), P50 AG016574 (Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center), U01 AG006786 (Mayo Clinic Study of Aging), Mayo Clinic Center for Regenerative Medicine, Mayo Clinic Center for Individualized Medicine, Mayo Clinic Neuroscience Focused Research Team, Cure MSA Foundation, 17K14966 (KO) from Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B), and a gift from Carl Edward Bolch, Jr. and Susan Bass Bolch. CL is the recipient of a FRSQ postdoctoral fellowship and is a 2015 Younkin Scholar supported by the Mayo Clinic Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias Genetics program.

Footnotes

-

Research project:

- Conception: K.O., Y.A.M., S.K., O.A.R.

- Organization: C.L., O.L.B., A.I.W. R.L.W., A.I.S., R.J.U., T.K., Z.K.W. P.A.L. W.S., D.W.D., G.B., O.A.R.

- Execution: K.O., Y.A.M., S.K., R.L.W., S.F.

-

Statistical Analysis:

- Design: M.G.H.

- Execution: E.V., M.G.H.

- Review and Critique: M.G.H.

-

Manuscript:

- Writing of the first draft: K.O., Y.A.M., M.G.H., S.K., O.A.R.

- Review and Critique: C.L., O.L.B., A.I.W. R.L.W., A.I.S., H.M.N., R.J.U., T.K., J.V.G., W.P.C., Z.K.W. P.A.L. W.S., D.W.D., G.B., O.A.R.

Financial Disclosure/Conflict of Interest:

K.O. receives research support by 17K14966 from Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B).

Y.A.M. reports no disclosures.

M.G.H. is an editorial board member of Parkinsonism and related disorders.

S.K. reports no disclosures.

C.L. receives a Fonds de recherche du Quebec – Sante postdoctoral fellowship.

O.L.B. reports no disclosures.

A.I. W. reports no disclosures.

R.L.W. reports no disclosures.

A.I.S. reports no disclosures.

E.V. reports no disclosures.

H.M.N. is a VINNMER/Marie Curie Fellow 2015-04905, receives support from the Alzheimer’s Association 2015-NIRG-339824 and serves as an associate editor of the Journal of Alzheimer’s disease and as a senior editor of Molecular Neurodegeneration.

S.F. reports no disclosures.

T.K. reports no disclosures.

R.J.U. receives research support from P50-NS072187, R01-NS057567, Abbott, Boston Scientific. R.J.U. serves as an associate editor of Neurology.

J.V.G. reports no disclosures.

W.P.C. reports no disclosures.

Z.K.W. receives research support from P50-NS072187. Z.K.W. serves as co-editor-in-chief of Parkinsonism and Related Disorders and Associate Editor of the European Journal of Neurology and is on the editorial boards of Neurologia i Neurochirurgia Polska, the Medical Journal of the Rzeszow University, and Clinical and Experimental Medical Letters; holds and has contractual rights for receipt of future royalty payments from patents for “A Novel Polynucleotide Involved in Heritable Parkinson’s Disease”; and receives royalties from publishing Parkinsonism and Related Disorders (Elsevier, 2013, 2014) and the European Journal of Neurology (Wiley Blackwell, 2013, 2014).

P.A.L reports no disclosures.

W.S. reports no disclosures.

D.W.D. receives support from P50-AG016574, P50-NS072187, P01-AG003949, and CurePSP: Foundation for PSP | CBD and Related Disorders. D.W.D. is an editorial board member of Acta Neuropathologica, Annals of Neurology, Brain, Brain Pathology, and Neuropathology and is editor in chief of American Journal of Neurodegenerative Disease and International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Pathology.

Guojun Bu received support from P50AG016574, RF1AG051504, R01AG027924, R01AG035355, R01AG046205, P01NS074969, and a grant from the Cure Alzheimer’s fund.

O.A.R. received support from R01-NS078086, P50-NS072187 and U54 NS100693 and the Michael J. Fox Foundation. O.A.R. is an editorial board member of American Journal of Neurodegenerative Disease and Molecular Neurodegeneration.

Financial Disclosures of all authors (for the preceding 12 months)

K.O. receives research support by 17K14966 from Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B).

Y.A.M. reports no disclosures.

M.G.H. reports no disclosures.

S.K. reports no disclosures.

C.L. receives a Fonds de recherche du Quebec-Sante postdoctoral fellowship.

O.L.B. reports no disclosures.

A. I.W. reports no disclosures.

R.L.W. reports no disclosures.

A.I.S. reports no disclosures.

E.V. reports no disclosures.

H.M.N. is a VINNMER/Marie Curie Fellow 2015-04905 and further receives support from the Alzheimer’s Association 2015-NIRG-339824 and Demensfonden.

S.F. receives research support by 15K19501 from JSPS KAKENHI. S.F. is an editorial board member of Parkinsonism & Related Disorders.

T.K. reports no disclosures.

R.J.U. receives research support from P50-NS072187, R01-NS057567, Abbott, Boston Scientific. R.J.U. is associate editor of Neurology.

J.V.G. reports no disclosures.

W.P.C. serves on the editorial boards of Parkinsonism & Related Disorders and as associate editor of Autonomic Neuroscience and Clinical Autonomic Research.

Z.K.W. receives research support from P50-NS072187. Z.K.W. serves as co-editor-in-chief of Parkinsonism and Related Disorders and Associate Editor of the European Journal of Neurology and is on the editorial boards of Neurologia i Neurochirurgia Polska, the Medical Journal of the Rzeszow University, and Clinical and Experimental Medical Letters; holds and has contractual rights for receipt of future royalty payments from patents for “A Novel Polynucleotide Involved in Heritable Parkinson’s Disease”; and receives royalties from publishing Parkinsonism and Related Disorders (Elsevier, 2013, 2014) and the European Journal of Neurology (Wiley Blackwell, 2013, 2014).

P.A.L reports no disclosures.

W.S. reports no disclosures.

D.W.D. receives support from P50-AG016574, P50-NS072187, P01-AG003949, and CurePSP: Foundation for PSP | CBD and Related Disorders. D.W.D. is an editorial board member of Acta Neuropathologica, Annals of Neurology, Brain, Brain Pathology, and Neuropathology and is editor in chief of American Journal of Neurodegenerative Disease and International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Pathology.

Guojun Bu received support from P50AG016574, RF1AG051504, R01AG027924, R01AG035355, R01AG046205, P01NS074969, and a grant from the Cure Alzheimer’s fund.

O.A.R. received support from R01-NS078086, P50-NS072187, U54 NS100693, Department of Defense W81XWH-17-1-0249 and the Michael J. Fox Foundation. O.A.R. is an editorial board member of American Journal of Neurodegenerative Disease and Molecular Neurodegeneration.

References

- 1.Gilman S, Wenning GK, Low PA, et al. Second consensus statement on the diagnosis of multiple system atrophy. Neurology. 2008;71(9):670–676. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000324625.00404.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bleasel JM, Wong JH, Halliday GM, Kim WS. Lipid dysfunction and pathogenesis of multiple system atrophy. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2014;2:15. doi: 10.1186/2051-5960-2-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu CC, Kanekiyo T, Xu H, Bu G. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: risk, mechanisms and therapy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9(2):106–118. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Federoff M, Schottlaender LV, Houlden H, Singleton A. Multiple system atrophy: the application of genetics in understanding etiology. Clin Auton Res. 2015;25(1):19–36. doi: 10.1007/s10286-014-0267-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trojanowski JQ, Revesz T Neuropathology Working Group on MSA. Proposed neuropathological criteria for the post mortem diagnosis of multiple system atrophy. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2007;33(6):615–620. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2007.00907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dickson DW, Liu W, Hardy J, et al. Widespread alterations of alpha-synuclein in multiple system atrophy. The American journal of pathology. 1999;155(4):1241–1251. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65226-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koga S, Ono M, Sahara N, Higuchi M, Dickson DW. Fluorescence and autoradiographic evaluation of tau PET ligand PBB3 to alpha-synuclein pathology. Mov Disord. 2017;32(6):884–892. doi: 10.1002/mds.27013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta neuropathologica. 1991;82(4):239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thal DR, Rub U, Orantes M, Braak H. Phases of A beta-deposition in the human brain and its relevance for the development of AD. Neurology. 2002;58(12):1791–1800. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.12.1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cairns NJ, Atkinson PF, Kovacs T, Lees AJ, Daniel SE, Lantos PL. Apolipoprotein E e4 allele frequency in patients with multiple system atrophy. Neurosci Lett. 1997;221(2–3):161–164. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(96)13316-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morris HR, Schrag A, Nath U, et al. Effect of ApoE and tau on age of onset of progressive supranuclear palsy and multiple system atrophy. Neurosci Lett. 2001;312(2):118–120. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02190-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morris HR, Vaughan JR, Datta SR, et al. Multiple system atrophy/progressive supranuclear palsy: alpha-Synuclein, synphilin, tau, and APOE. Neurology. 2000;55(12):1918–1920. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.12.1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toji H, Kawakami H, Kawarai T, et al. No association between apolipoprotein E alleles and olivopontocerebellar atrophy. Journal of the neurological sciences. 1998;158(1):110–112. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(98)00099-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Josephs KA, Tsuboi Y, Cookson N, Watt H, Dickson DW. Apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 is a determinant for Alzheimer-type pathologic features in tauopathies, synucleinopathies, and frontotemporal degeneration. Archives of neurology. 2004;61(10):1579–1584. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.10.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sailer A, Scholz SW, Nalls MA, et al. A genome-wide association study in multiple system atrophy. Neurology. 2016;87(15):1591–1598. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gan-Or Z, Montplaisir JY, Ross JP, et al. The dementia-associated APOE epsilon4 allele is not associated with rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. Neurobiology of aging. 2017;49:218e213–218.e215. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kisos H, Pukass K, Ben-Hur T, Richter-Landsberg C, Sharon R. Increased neuronal alpha-synuclein pathology associates with its accumulation in oligodendrocytes in mice modeling alpha-synucleinopathies. PloS one. 2012;7(10):e46817. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.