Abstract

Telomere biology disorders, which are characterized by telomerase activity haploinsufficiency and accelerated telomere shortening, most commonly manifest as degenerative diseases. Tissues with high rates of cell turnover, such as those in the hematopoietic system, are particularly vulnerable to defects in telomere maintenance genes that eventually culminate in bone marrow (BM) failure syndromes, in which the BM cannot produce sufficient new blood cells.

Here, we review how telomere defects induce degenerative phenotypes across multiple organs, with particular focus on how they impact the hematopoietic stem and progenitor compartment and affect hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) self-renewal and differentiation. We also discuss how both the increased risk of myelodysplastic syndromes and other hematological malignancies that is associated with telomere disorders and the discovery of cancer-associated somatic mutations in the shelterin components challenge the conventional interpretation that telomere defects are cancer-protective rather than cancer-promoting.

Keywords: Telomere biology disorders, hematopoietic stem cells, myelodysplastic syndrome, DNA damage response

1. Telomeres and telomerase

Telomeres are ribonucleoprotein complexes that protect chromosome ends from degradation, fusion, and recombination. Human telomeres are composed of 10–15 kb of double-stranded DNA repeated sequences (5′-TTAGGG-3′) ending in a 3′ single-stranded G-rich overhang that invades the double-stranded DNA region and forms a structure called the telomere loop (t-loop) (Doksani et al., 2013; Griffith et al., 1999). The shelterin complex interacts with the t-loop to safeguard the chromosome ends from nuclease degradation and aberrant activation of the DNA damage response and regulates telomerase access to telomere ends (de Lange, 2005).

Telomere length is maintained by telomerase, a specialized ribonucleoprotein complex that includes a specialized reverse transcriptase catalytic subunit, telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT), and an RNA template, telomerase RNA component (TERC), both of which are necessary to catalyze the synthesis and extension of telomeric DNA (Feng et al., 1995; Greider and Blackburn, 1985; Greider and Blackburn, 1987; Greider and Blackburn, 1989). Active telomerase is associated with the H/ACA small nuclear ribonucleoprotein complex, which includes dyskerin (which recognizes the H/ACA sequence domain of TERC), nuclear protein 10 (NOP10), ribonucleoprotein NHP2, and NOLA1 (also known as GAR1), and regulates telomerase stability and activity (Hamma and Ferre-D’Amare, 2010). Active telomerase also contains the telomerase Cajial body protein 1 (TCAB1), which associates with TERC and regulates telomerase localization to nuclear Cajial bodies (Venteicher et al., 2009).

Telomerase expression and activity are strictly controlled by multilayer regulatory mechanisms, including telomerase trafficking in the nuclei of living cells, post-transcriptional and translational modifications, and dynamic interplays with the shelterin complex, to ensure telomere length homeostasis. The disruption of this regulatory network inexorably perturbates telomere length homeostasis and results in dysfunctional (i.e., shorter or longer) telomeres and human diseases. Telomerase is absent in most human somatic tissues but highly expressed in early proliferative progenitor germ cells, stem cells, and expanding activated lymphocytes (Wright et al., 1996). Telomerase is also upregulated or reactivated in 90% of cancer cells (Kim et al., 1994), which suggests that telomere maintenance is permissive and required for continued cell proliferation (Shay and Wright, 2011).

In the absence of telomerase, the linear nature of eukaryotic chromosomes results in telomere shortening during every cell division, a phenomenon known as the end-replication problem, owing to the failure of DNA polymerase to completely synthesize the extreme terminus of the lagging DNA strand (de Lange, 2009). However, given that only a few telomeres are elongated in each cell cycle (Teixeira et al., 2004), even cells that maintain telomerase activity, such as hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), undergo telomere shortening as they age. The progressive telomere attrition, which occurs over the natural lifespan of humans, limits the proliferation of human cells to a finite number of cell divisions by inducing checkpoint activation, replicative senescence, differentiation, or apoptosis and triggers several aspects of human aging phenotypes (Aubert and Lansdorp, 2008). Thus, telomeres function as a clock of replicative lifespan.

2. The shelterin complex

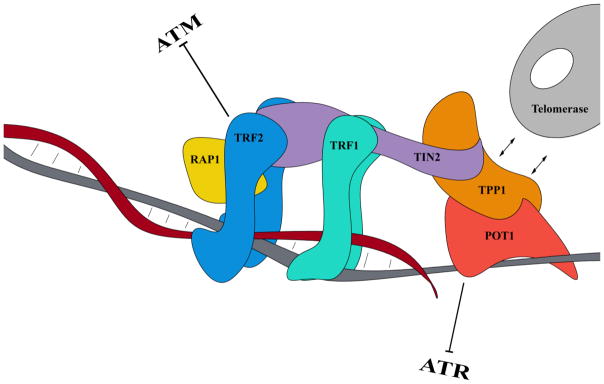

Shelterin, a 6-protein, telomere-specific complex consisting of telomere repeat factor 1 (TRF1), telomere repeat factor 2 (TRF2), TRF1-interacting nuclear factor 2 (TIN2), repressor activator protein 1 (RAP1), TPP1 (TINT1/PTOP1/PIP1; encoded by the gene ACD), and protection of telomeres 1 (POT1), represses the DNA damage response at telomeres and protects telomere ends from being processed by several DNA double-strand break repair pathways. The protective function of shelterin is mediated by the formation of the t-loop structure that sequesters telomere ends from the DNA damage surveillance (de Lange, 2005; Maciejowski and de Lange, 2017). Shelterin binds to the double-stranded TTAGGG repeats through TRF1 and TRF2, while POT1 recognizes the single-stranded telomeric overhangs by its N-terminal oligosaccharide/oligonucleotide-binding (OB) fold domain (Loayza and De Lange, 2003) and forms a heterodimer with TPP1 by its C-terminal binding protein domain (Ye et al., 2004). The POT1/TPP1 heterodimer is linked to TRF1 and TRF2 through TIN2, which forms a bridge between TTP1/POT1 and the double-stranded DNA–binding TRF1/TRF2 components of shelterin (Takai et al., 2011). RAP1 is recruited to telomeres by binding to TRF2 (Li et al., 2000) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The shelterin complex.

The shelterin complex is a 6-protein, telomere-specific complex consisting of TRF1, TRF2, TIN2, RAP1, TPP1, and POT1. TRF1 and TRF2 bind to the double-stranded TTAGGG repeats, whereas POT1 recognizes the single-stranded telomeric overhang. The shelterin complex safeguards the chromosome ends from nuclease degradation and aberrant activation of the DNA damage response and regulates telomerase access to telomere ends. TRF2 represses the activation of the ATM-dependent DNA damage response and NHEJ, while POT1 (together with RAP1) prevents the activation of ATR-dependent signaling and suppresses HR.

Telomere deprotection, which is caused by critically short telomeres that lose the shelterin binding sites or by genetic alterations that affect the function of the shelterin components, results in the aberrant recognition and processing of telomere as a DNA break and leads to deleterious consequences such as cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, senescence, and eventually genomic instability (Sfeir and de Lange, 2012). The repair of dysfunctional telomeres can be mediated by the canonical or alternative non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathways or by the homologous recombination (HR) pathway. Canonical NHEJ activation results in end-to-end chromosome fusions and dicentric chromosomes, which mediate amplifications and deletions across the genome, whereas HR activation leads to the exchange of DNA sequences between sister chromatids and recombination that induces inversions, translocations, terminal deletions, and eventually the alternative lengthening of telomeres (ALT), a mechanism of telomere maintenance that is independent of telomerase. ALT occurs in a small subset of genomically unstable cancers that are telomerase-negative and leads to significant telomere length heterogeneity, extrachromosomal linear and circular telomeric DNA, and elevated telomere-sister chromatid exchange (Bryan et al., 1997; Dunham et al., 2000).

Beyond its telomere-protective function, shelterin plays a critical role in telomerase-mediated telomere length homeostasis at each telomere by recruiting telomerase to telomeres, thereby enhancing telomerase processivity (Nandakumar et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2007) and disrupting G-quadruplex structures in telomeric DNA during replication (Zaug et al., 2005) (positive regulation), or by capping the single-stranded DNA telomere overhangs, restricting their access to telomerase, and preventing telomere elongation (negative regulation) (Loayza and De Lange, 2003). The negative regulation of telomerase activity at each telomere allows telomerase to elongate only the shorter telomeres and prevents telomeres from becoming excessively long (since the amount of shelterin bound to a telomere is proportional to the number of the TTAGGG repeats, longer telomeres have a greater probability to inhibit telomerase) (de Lange, 2005). Although this negative feedback regulation of telomerase requires the single-stranded DNA-binding activity of POT1 (Loayza and De Lange, 2003), the exact mechanisms of this feedback remain to be elucidated and seem to be more complex than the shelterin-mediated steric blocking of telomerase access to the 3′ overhangs (Hockemeyer and Collins, 2015; Schmutz and de Lange, 2016).

Shelterin also cooperates with the CST complex, a DNA polymerase alpha primase accessory factor consisting of the proteins CTC1, STN1, and TEN1, to regulate telomerase and DNA polymerase alpha-primase access to telomeres. The CST complex also rescues replication fork stalling during telomere replication and arrests telomere elongation through tight and specific interaction with the telomeric overhang (Rice and Skordalakes, 2016).

Because shelterin plays an essential role in cellular viability, the deletion of each shelterin component, except RAP1, in mice causes embryonic lethality; thus, only pathological mutations in TIN2 (Sarper et al., 2010; Savage et al., 2008; Walne et al., 2008) and more rarely in TPP1 (Guo et al., 2014; Kocak et al., 2014) have been identified in humans. These mutations are associated with the particularly severe and early-onset forms of telomere disorders such as Hoyeraal-Hreidarsson syndrome and Revesz syndrome (Holohan et al., 2014). Most of the TIN2 mutations identified in humans are missense point mutations that cluster in exon 6a (amino acids 269–298) near the TRF1-binding site. However, these mutations do not affect the binding of TIN2 to TRF1 or to telomeres (Yang et al., 2011), and the molecular mechanisms by which they induce telomere shortening are not completely understood. Interestingly, in a mouse model carrying the K280E mutation—one of the TIN2 mutations found in humans—telomere shortening occurred at least partially independently of telomerase-mediated telomere maintenance (since the mutation accelerated telomere shortening and consequent degenerative phenotypes in both the absence and presence of the RNA component of telomerase) and resulted in the loss of the telomeric DNA–and ATR-dependent, but ATM–independent, activation of the DNA damage response at telomeres (Frescas and de Lange, 2014).

3. Telomere biology disorders caused by critically short telomeres

One prominent example of the direct effects that dysfunctional telomeres have in humans is a spectrum of syndromes caused by germline mutations in telomere maintenance genes. The prototype of these telomere biology disorders is dyskeratosis congenita (DKC) (Savage, 2014; Savage and Alter, 2009), which is caused by mutations in genes encoding the telomerase components TERT and TERC (Vulliamy et al., 2001; Vulliamy et al., 2005), the shelterin components TIN2 (Sarper et al., 2010; Savage et al., 2008; Walne et al., 2008) and TPP1 (Guo et al., 2014; Kocak et al., 2014), and the telomerase accessory proteins dyskerin (Heiss et al., 1998), TCAB1 (Zhong et al., 2011), NOP10 (Walne et al., 2007), and NHP2 (Savage, 2014). Telomere biology disorders, which are characterized by telomerase activity haploinsufficiency and accelerated telomere shortening, most commonly manifest as degenerative diseases such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, bone marrow (BM) failure, cryptogenic liver cirrhosis, and gastrointestinal disease (Armanios, 2013; Batista et al., 2011; Holohan et al., 2014; Jonassaint et al., 2013).

Although their symptoms and the age of onset are highly variable and depend on the extent of the telomere length defects, telomere biology disorders show similar underlying molecular mechanisms and include a unique syndrome spectrum defined by the short telomere defect (Armanios, 2013; Armanios and Blackburn, 2012). Individuals within the same family who have the same telomere mutation can present with different disease penetrance and manifest distinct phenotypic effects. Since telomere length is hereditable (Goldman et al., 2005), disease anticipation (an earlier onset and worsening of symptoms with successive generations) also has been observed in several multi-generation families affected by autosomal dominant telomere syndromes owing to the progressive telomere shortening occurring in later generations (Armanios et al., 2005; Vulliamy et al., 2004). Moreover, telomerase haploinsufficiency due to the same mutation can induce different clinical phenotypes both within a given family and between families (Kirwan et al., 2009). This finding attests to the importance of both telomere length and telomerase activity in determining disease onset and clinical presentation (Armanios, 2009).

The generation and characterization of telomerase-deficient mice have greatly informed our understanding of telomere-mediated disease mechanisms and demonstrated that telomere shortening per se is sufficient to determine the degenerative phenotypes of high-turnover tissues observed in human telomere syndromes. However, most laboratory mouse strains have significantly longer telomeres than humans do and thus develop organ failure, tissue atrophy, decreased fecundity, and widespread degenerative phenotypes only after multiple generations of crossing, once telomeres become critically short. More recently, telomerase haploinsufficient mice on the CAST/EiJ background, which have a telomere length and distribution that mimic those of humans (Hemann and Greider, 2000), have faithfully recapitulated the BM failure and immune senescence phenotype observed in patients with DKC (Armanios et al., 2009). Importantly, in these mice, the degenerative phenotypes, which affect slow-turnover tissues such as the lung and liver, occur only after chronic injury. These findings suggest that telomere defects represent one of the multiple steps necessary to promote slow-turnover organ failure and explain why idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, liver fibrosis and cirrhosis in some DKC patients does not occur until adulthood (Alder et al., 2015; Alder et al., 2011).

Like telomerase-deficient mice, later generation (G2/G3) knock-in mice carrying the TIN2 mutation K280E develop progressive telomere shortening–induced degenerative phenotypes that affect high-turnover tissues, such as fertility loss and mild pancytopenia that involves all hematopoietic lineages.

4. Telomere dysfunction and hematopoietic defects

Tissues with high rates of cell turnover, such as those in the skin, in the intestinal crypts and in the hematopoietic system, are particularly vulnerable to defects in telomere maintenance genes (Lee et al., 1998; Rudolph et al., 1999). The hematopoietic defects are the most common clinical manifestations of telomere biology disorders in children and young adults and lead to severe diseases that culminate in BM failure syndromes (Goldman et al., 2008; Yamaguchi et al., 2005), in which the BM cannot produce sufficient new blood cells owing to a marked reduction in the number and function of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs). Indeed, telomerase plays a critical role in preventing telomere shortening and maintaining the replicative lifespan of HSCs throughout the lifespan of an organism (Allsopp et al., 2003a), as evidenced by the impaired repopulating capability of HSCs with critically short telomeres as well as these cells’ reduced capacity to respond to stresses such as wounds, hematopoietic ablation, and serial transplantation (Hao et al., 2005; Rossi et al., 2007; Rudolph et al., 1999). However, telomerase overexpression does not extend the replicative lifespan of HSCs in transplantation experiments even though long telomeres are maintained (Allsopp et al., 2003b), which suggests that although telomerase is required for the maintenance of the replicative lifespan of HSCs, additional telomere length-independent mechanisms contribute to limiting their function.

Studies of the HSPC compartment in patients with DKC have shown that such patients have dramatically fewer CD34+ BM cells even before the onset of the severe symptoms of BM failure (Goldman et al., 2008). Similarly, the number of Lin−c-Kit+Sca1+CD34−CD150+ HSCs is significantly decreased in late-generation telomere-dysfunctional mice (Raval et al., 2015). These findings suggest that the BM failure phenotype induced by telomere defects is caused by both the functional impairment and numerical exhaustion of HSCs.

Although the molecular mechanisms that lead to HSC failure are not completely understood, studies in mice with critically short telomeres have demonstrated that the deletion of the cell cycle inhibitor CDKN1A (p21) improves the self-renewal capability and function of telomere-dysfunctional HSCs and prolongs the lifespan of telomerase-deficient mice with dysfunctional telomeres without accelerating chromosomal instability or cancer formation. These results demonstrate that p21-dependent mechanisms limit HSC maintenance and impair HSC repopulation capability in response to telomere dysfunction by compromising HSCs’ self-renewal and maintenance of “stemness” (Choudhury et al., 2007).

Beyond the HSC failure phenotype, telomere dysfunction also impairs HSC lineage commitment, biases HSC differentiation towards the myeloid lineage (Ju et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2016), and induces immunosenescence (Armanios et al., 2009), as evidenced by the profound B- and T-cell lymphopenia observed in the peripheral blood of mice with short telomeres and by the inability of telomere-dysfunctional immune cells to activate a robust immune response after antigen exposure (Armanios et al., 2009). These results are consistent with the observation that patients with DKC have defective antibody production and humoral immunity and are inclined to develop opportunistic infections similar to those of patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (Armanios et al., 2009; Knudson et al., 2005).

5. Critically short telomere length: tumor suppressor or tumor promoter?

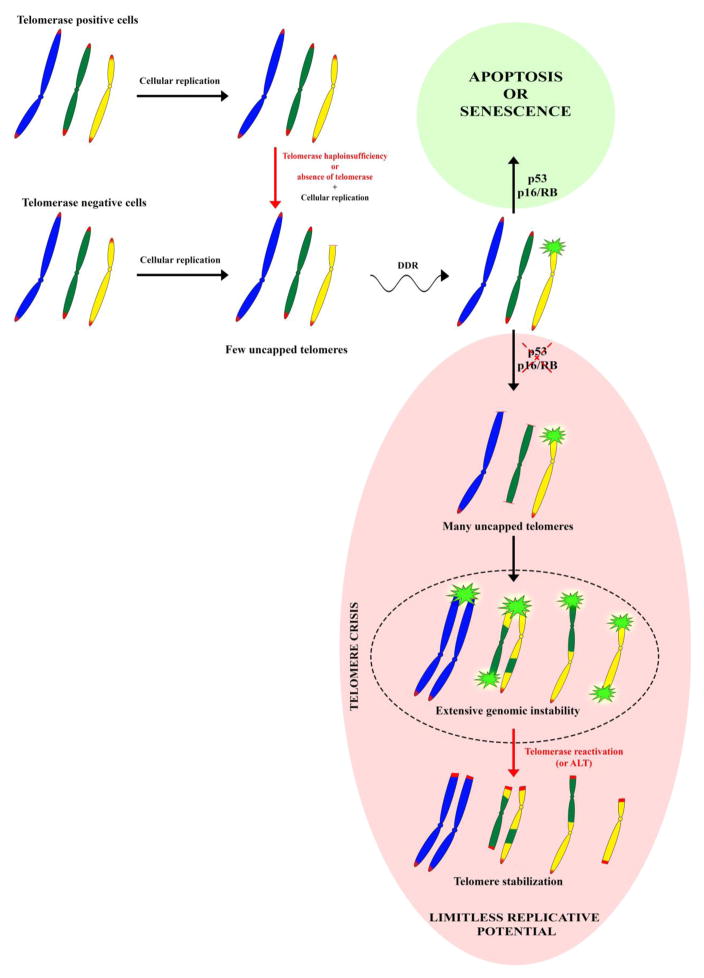

Telomere dysfunction, which results from excessive telomere attrition or the disruption of telomere structure, limits cellular proliferation and is considered an initial barrier to cellular immortalization and tumorigenesis (Shay and Wright, 2005). In the setting of intact p53 or p16/retinoblastoma (RB) checkpoint signaling, dysfunctional telomeres act as potent tumor suppressors by engaging DNA damage response pathways that activate replicative senescence and/or apoptosis (d’Adda di Fagagna et al., 2003). Nevertheless, when telomere dysfunction is combined with p53 or p16/RB pathway impairment, which deactivates DNA-damage signaling, cell division can extend over the senescence limit, resulting in telomere crisis. Studies in telomerase-deficient mice have demonstrated that p53-dependent checkpoints rather than p16 checkpoints are mostly responsible for suppressing tumor formation in the setting of telomere dysfunction and that p53 deletion but not p16 deletion cooperates with telomere dysfunction in inducing tumor formation (Greenberg et al., 1999; Khoo et al., 2007).

Telomere crisis is characterized by extensive genomic instability and widespread apoptosis (Davoli and de Lange, 2012). Progressive telomere shortening eventually leads to the telomere uncapping that generates DNA double-strand breaks and increases the risk of the end-to-end fusion of unprotected chromosomes, resulting in genetic aberrations and mitotic mis-segregation (Hackett et al., 2001; Lian et al., 2017; Maciejowski and de Lange, 2017).

Cancer cells acquire mechanisms to stabilize their telomeres during telomere crisis to limit genomic instability and escape the anti-proliferative barrier imposed by telomere dysfunction (Kim et al., 1994). Most of the time, this is accomplished through telomerase reactivation, but on rare occasions, cancer cells can elongate telomeres via the activation of ALT (Bryan et al., 1997; Feldser et al., 2003; Maser and DePinho, 2002) (Figure 2). TERT promoter mutations (TPMs) have recently been found in about 90% of human cancers derived from tissues with low rates of self-renewal that in physiological conditions do not express telomerase (Horn et al., 2013; Killela et al., 2013; Rachakonda et al., 2013), whereas mutations of the telomere-binding proteins alpha thalassemia/mental retardation syndrome X-linked (ATRX) or death-domain associated protein (DAXX), which are associated with ALT, occur in approximately 10–15% of tumors (Heaphy et al., 2011).

Figure 2. Telomere shortening and genomic instability.

In the absence of telomerase, the linear nature of eukaryotic chromosomes results in telomere shortening during every cell division. Even cells that maintain telomerase activity, such as stem cells, undergo telomere shortening as they age. Unprotected telomeres engage DNA damage response (DDR) pathways that activate replicative senescence and/or apoptosis. Cells with defective p53 or p16/RB pathway function, which deactivates DNA-damage signaling, continue to divide. As many telomeres become critically short owing to the prolonged cell proliferation, uncapped telomeres can undergo end-to-end fusion and recombination, which leads to extensive genomic instability (i.e., telomere crisis). Eventually telomerase reactivation or activation of the ALT pathway, which restores telomere function, limits genomic instability and allows cells to escape the anti-proliferative barrier imposed by telomere dysfunction.

Although TPMs occur frequently in human cancers, their role in cancer initiation, progression, and immortalization is unclear. Recent findings have shown that TPMs contribute to melanomagenesis by a 2-step mechanism (Chiba et al., 2017). In the early phases of tumorigenesis, when oncogenic gain-of-function mutations and checkpoint inactivation occur in melanocytic nevi, the acquisition of TPMs can enable cells to bypass telomere shortening–induced replicative senescence by conferring extended proliferation capability. However, TPMs can induce only a moderate level of telomerase expression that is not sufficient to counteract the progressive telomere shortening that occurs over prolonged proliferation. In the late phases of tumorigenesis, when telomeres become critically short and the rate of genomic instability increases after prolonged rounds of cellular divisions, TPMs are permissive to the acquisition of secondary events that further increase telomerase activity, allow cells to overcome telomere crisis, and induce malignant transformation (Chiba et al., 2017; Shay, 2017). However, these secondary events are yet to be determined.

Tumors that arise from telomerase-positive stem cells with high rates of self-renewal and/or proliferation have lower frequencies of TPMs than do tumors that arise from telomerase-negative stem cells (Killela et al., 2013). This finding suggests that tumors originating from telomerase-competent stem cells do not require TPMs to stabilize their telomeres and that these tumors’ constitutive telomerase activity could by itself permit the acquisition of additional alterations that drive carcinogenesis.

Consistent with the evidence that telomerase reactivation promotes cancer initiation or progression only in the setting of pre-existing precancerous lesions or established neoplasms (Ding et al., 2012), telomerase reactivation in a mouse model of telomere shortening with intact checkpoint signaling and advanced degenerative phenotypes alleviated DNA damage signaling–induced cellular checkpoint responses in multiple high-turnover organ systems without inducing cancer formation (Jaskelioff et al., 2011). Similarly, the ectopic expression of TERT in normal human fibroblasts extended the lifespan but did not lead to cancer (Morales et al., 1999).

The molecular mechanisms by which TMPs drive telomerase reactivation are not completely understood. Recent findings across multiple cancers have shown that TPMs create novel consensus binding sites for E-twenty-six (ETS) family transcription factors (Hollenhorst et al., 2011) and cause a dramatic epigenetic switch from a repressed to an active chromatin state that enables the binding of the transcription factor GABPA and the recruitment of RNA polymerase 2 to the proximal mutant TERT promoter (Stern et al., 2015). Mechanistically, the recruitment of GABPA to the TERT promoter mediates a novel long-range chromatin intrachromosomal interaction between the TERT promoter and the mutant TERT promoter–interacting region on chromosome 5, which allows the enrichment of active histone marks and the recruitment of chromatin remodelers on the TERT promoter to drive TERT transcription (Akincilar et al., 2016).

6. Telomere defects and myelodysplastic syndrome: a paradoxical connection

Patients with germline mutations of telomere maintenance genes are at significant risk of developing cancers, mostly those involving high-turnover tissues such as those in the hematopoietic system (Alter et al., 2010; Alter et al., 2009). Among the hematopoietic malignancies, myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) are most likely to occur in patients with germline mutations of telomere maintenance genes (Alter et al., 2010; Kirwan et al., 2009). This observation, together with evidence that telomere shortening, which naturally occurs with aging, is associated with an increased risk of MDS in older populations (Rollison et al., 2008), apparently contradicts the conventional interpretation that telomere dysfunction is cancer-protective rather than cancer-promoting (Holohan et al., 2014).

That patients with dysfunctional telomeres have an increased incidence of MDS is counterintuitive. MDS is characterized by the clonal expansion of genetically aberrant HSCs, which have sustained self-renewal and proliferative capacity (Will et al., 2012). Conversely, telomere defects drive HSC decline, thereby compromising their self-renewal, repopulating capacity, and differentiation (Rossi et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2012), and culminate in severe ineffective hematopoiesis (Yamaguchi et al., 2005). This suggests that telomere-dysfunctional HSCs that evolve to MDS are prone to acquire secondary genetic alterations that enable HSCs to bypass replicative exhaustion and clonally expand. The predisposition to the acquisition of secondary genetic aberrations could be the consequence of the BM failure phenotype imposing a selective pressure on the few remaining HSCs or of the telomere defects themselves (Armanios, 2009).

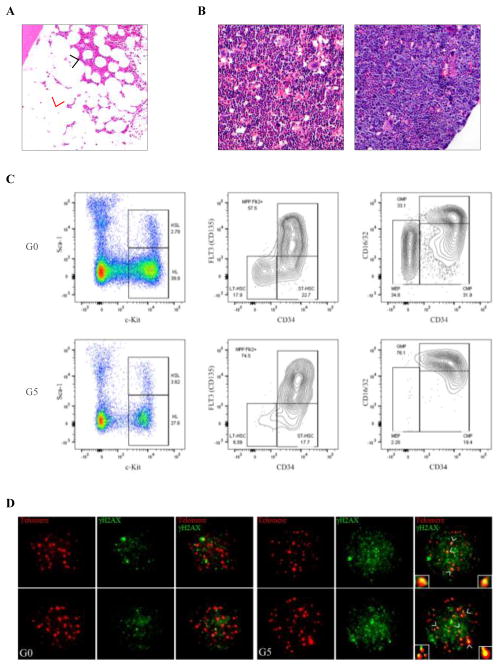

To dissect the molecular mechanisms by which telomere-dysfunctional HSCs overcome their compromised self-renewal capability during MDS pathogenesis, we analyzed the genetic aberrations in BM cells from patients with germline inactivating TERT mutations and critically short telomeres who developed MDS associated with normal or increased BM cellularity (Figure 3A, unpublished data). Cytogenetic analysis showed chromosomal aberrations and translocations in the BM cells of 2 of the 4 patients in our preliminary cohort. MDS or AML with increased BM cellularity and chromosomal aberrations was also previously observed in individuals with TERT or TERC mutations within the same family (Kirwan et al., 2009). Whole exome sequencing analysis of BM mononuclear cells (and corresponding T-cell germline controls) from these 2 patients revealed exonic somatic mutations in the coding regions of genes whose biological functions in disease pathogenesis have yet to be determined.

Figure 3. Hematopoietic phenotypes induced by telomere dysfunction.

A) H&E-stained section of a BM biopsy specimen from a representative patient with a germline inactivating mutation of TERT and critically short telomeres who developed MDS. The black arrowhead indicates areas of BM aplasia and the red arrowhead indicates MDS-associated hypercellularity. B) H&E-stained sections of BM biopsy specimens from representative G0 (left panel) and G5 (right panel) mice. C) Flow cytometry analysis of the Lineage−Sca1+c-Kit+ (LSK) stem cell and Lineage−c-Kit+ (LK) progenitor cell compartment (left panel) of representative aged G0 (upper panel) and G5 (bottom panel) mice. Flow cytometry analysis of the long-term (LT)-HSC and multipotent progenitor (MPP) populations in the LSK compartment (middle panel) and the megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitor (MEP), granulocyte-macrophage progenitor (GMP), and common myeloid progenitor (CMP) populations in the LK compartment (right panel). D) Representative telomere-FISH and anti-γH2AX immunofluorescence in Lineage−Sca1+c-Kit+CD34−CD135− LT-HSCs sorted from 2-month-old G0 (left panel) and G5 (right panel) mice (telomere: red; anti-γH2AX: green; co-localization: yellow).

How MDS cells can tolerate genomic instability and compensate for the reduced telomere function caused by loss-of-function mutations in TERT to clonally expand also remains unclear. It is possible that, when combined with other acquired oncogenic aberrations, HSCs’ residual telomerase activity is sufficient to sustain the low rate of proliferation that is typical of MDS. Alternatively, genetically aberrant HSCs with a replicative advantage and reduced telomerase activity could acquire additional alterations, including the spontaneous reversion of the mutant allele to a functional allele, to activate telomerase expression. The somatic reverting mosaicism of germline mutations in TERC induced by the acquired segmental isodisomy of chromosome 3q, which includes TERC, has been observed in several patients with autosomal dominant DKC (Jongmans et al., 2012). Similarly, TERT promoter mutations can occur in patients with familial pulmonary fibrosis caused by germline loss-of-function mutations in telomere maintenance genes, which underscores the selective force these compensatory mutations have in counteracting progressive telomere shortening. In the absence of additional oncogenic alterations, these telomere maintenance compensatory events are insufficient to immortalize cells and cause cancer (Maryoung et al., 2017); however, they could allow clonal evolution if they are acquired in the context of precancerous lesions.

Interestingly, the administration of the telomerase activator danazol (Townsley et al., 2016) to mitigate the symptoms of pulmonary fibrosis in one of our MDS patients with a TERT germline mutation and abnormal karyotype increased the number of aberrant BM metaphases (unpublished data), which suggests that telomerase activation can sustain these cells’ extended clonal proliferation and that telomerase-activating therapy in the setting of telomere dysfunction–induced genomic instability can enable rapid clonal evolution. Telomerase-activating therapies are a potential option for patients with diseases caused by defective telomere maintenance, including MDS (Townsley et al., 2016), but the long-term effects of telomerase activation on MDS caused by defective telomeres are not known. These effects might depend on the time at which telomerase reactivation occurs. In the very early stages of telomere attrition, telomerase reactivation could prevent genomic instability or rescue the growth potential of normal, non-altered HSPCs, thus increasing their proliferative competition, which in turn may lead to the suppression of low-frequency aberrant cell clones. However, in the presence of extensive genomic instability and p53 checkpoint signaling inactivation, telomere dysfunction followed by telomerase reactivation could enable the expansion of aberrant clones with acquired telomerase-driven proliferative potential and drive disease progression.

These observations suggest that the predisposition of patients with telomere disorders to develop hematological cancers may be dictated by the extent of telomere length defects that depend on not only the telomere mutation but also other genetic or environmental factors and by the degree to which the telomere mutation affects telomerase activity. That is, cancer-prone stem cells could have critically short telomeres and thus be predisposed to genomic instability yet maintain sufficiently high telomerase activity to sustain their growth once they acquire secondary genetic lesions that confer a replicative or survival advantage. Supporting this hypothesis, individuals with the hypomorphic germline TERT variant A1062T have an increased risk of developing AML associated with complex karyotype and chromosomal rearrangements (Calado et al., 2009). Although this mutation slightly decreases telomerase activity (the telomerase activity of the A1062T allele has been reported to be normal or reduced to 60% of wild type (Alder et al., 2008; Calado et al., 2009)), it still affects telomere length and predisposes cells to genomic instability, probably in combination with other genetic mechanisms. Thus, mutant HSCs’ residual telomerase activity could be sufficient to maintain the clonal expansion of the cells once they acquire tumorigenic potential.

Our other MDS patients with TERT mutations and critically short telomeres had normal karyotypes, which suggests that mechanisms other than genomic instability can drive the development of telomere defect–associated MDS. Thus, next-generation sequencing of BM cells from these patients is necessary to clarify whether MDSs are indeed clonal malignancies rather than early-stage, MDS-like phenotypic conditions driven by telomere defects. Indeed, telomere defects themselves may be responsible for the MDS-like phenotypes, such as aberrant differentiation and dysplasia, observed in these patients. These defects may represent the initiating event of a multistep process that eventually can lead to the acquisition of genomic instability and clonal evolution.

Efforts to improve our understanding of the role of telomere dysfunction and telomerase in MDS pathogenesis have been limited by the extreme rarity of MDS caused by mutations in telomere maintenance genes and by the historical lack of relevant mouse systems in which the clonal evolution of this disease can be accurately modeled. Most experimental evidence of the causal role that telomere dysfunction has in MDS pathogenesis derives from our recent studies (Colla et al., 2015) employing an inducible knock-in telomerase mouse model, TERTER, which is engineered to encode a telomerase reverse transcriptase–estrogen receptor fusion protein that can be reactivated by 4-hydroxytamoxifen treatment (Jaskelioff et al., 2011). The TERTER model is a highly relevant physiological system that mimics the adverse effects of the endogenous telomere shortening induced by mutations in telomere maintenance genes and allows for the dissection of the molecular mechanisms by which telomere dysfunction and subsequent telomerase reactivation contribute to MDS initiation and eventually progression.

Our analysis of the hematopoietic system of TERTER/ER mice at the fourth and fifth generation (G4/G5) revealed significant cytopenias in the peripheral blood, a decline in lymphopoiesis, slight anemia, and moderate granulo-monocytosis in advancing age. BM hyper-cellularity, severe tri-lineage dysplasia, and an increased myeloid-to-erythroid progenitor ratio in the absence of increased apoptosis were consistent with myeloid-skewed differentiation and ineffective hematopoiesis (Figure 3B). This hematopoietic phenotype is different from the BM failure condition previously observed in successive generations of CAST/EiJ mTR+/− mice (Hao et al., 2005) and further underlines how differences in telomere length can result in a heterogeneous spectrum of phenotypic manifestations.

We also found that, compared with that of G0 TERTER/+ mice with intact telomeres, the progenitor compartment of G4/G5 TERTER/ER mice had a significantly higher frequency and absolute number of granulocyte-macrophage progenitors with a concomitant loss of megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitors and a slight reduction of common myeloid progenitors. G4/G5 TERTER/ER mice also showed a progressive decrease in the number of long-term (LT)-HSCs and concomitant expansion of downstream multipotent progenitors during aging (Figure 3C). This HSPC architecture is reminiscent of that observed in MDS patients at high risk for leukemic transformation, who are characterized by a decreased frequency of LT-HSCs and increased number of downstream multipotent lymphoid-primed progenitors.

Although the cytogenetic analysis of BM cells from 3-month-old G4/G5 TERTER/ER mice showed an increased frequency of chromosomal breaks and fusions (Colla et al., 2015), clonal chromosomal aberrations occurred only during disease progression. Moreover, whole exome sequencing analysis of 12 samples of BM mononuclear cells isolated from 3-month-old G4/G5 TERTER/ER mice with phenotypic signs of MDS did not have exonic somatic mutations with high allelic burden (unpublished data).

Consistent with the absence of clonal hematopoiesis in early-stage telomere dysfunction, early-stage telomerase reactivation by 4-hydroxytamoxifen administration for 40 days reduced DNA damage signaling, partially reversed defective progenitor differentiation, and prevented MDS phenotypes, which suggests that DNA damage–induced telomere dysfunction is the initiating event that drives classic MDS phenotypes in the absence of MDS-associated gene mutations or genetic alterations. A similar normalization of the DNA damage response and the rescue of defective erythropoiesis after telomerase reactivation has also been observed in another TERT knockout mouse model that contained a Cre-inducible Lox-Stop-Lox cassette (Raval et al., 2015).

The HSPC compartment in the early-generation TERTER/ER mice (G1) without telomere dysfunction did not show signs of aberrant differentiation, which demonstrates that the hematopoietic phenotype in G4/G5 TERTER/ER mice can be attributed to telomere shortening–induced DNA damage activation (Figure 3D) and not to the absence of telomerase per se. These findings are consistent with previous studies showing that phenotypes of TERT haploinsufficient mice are due to short telomeres and not the telomerase-independent function of TERT (Strong et al., 2011).

Experiments involving the transplantation of LT-HSCs isolated from 3-month-old telomere-dysfunctional mice into wild-type congenic recipients revealed that the level of donor-derived skewed myeloid differentiation involving the progenitor compartment was similar to that observed at a steady state in the same telomere-dysfunctional mice before transplantation. This suggests that impaired progenitor differentiation and associated MDS phenotypes are the result of cell-intrinsic defects in telomere-dysfunctional hematopoietic cells. These results are consistent with the observation that allogeneic transplantation can cure patients with germline mutations affecting telomere maintenance who have developed BM failure syndromes or hematological disorders (Stanley and Armanios, 2015). However, our study did not exclude the possibility that the BM microenvironment also contributes to impaired myeloid differentiation in older telomere-dysfunctional mice. Indeed, previous studies have demonstrated that a telomere-dysfunctional systemic environment limits HSC function and organ homeostasis (Ju et al., 2007) and that the BM microenvironment contributes to the pathogenesis and clinical features of MDS and BM failure syndromes (Li and Calvi, 2017).

Although the HSPC architecture of aged G4/G5 TERTER/ER mice recapitulated that observed in MDS patients at high risk for leukemic transformation, the hematological disease exhibited a constrained progression phenotype that was associated with a low occurrence of AML transformation (5%) and an inhibited proliferation of myeloid blasts (total white blood cell count < 15×103/μL). These results suggest that after telomere dysfunction enables MDS initiation, ongoing telomere dysfunction and associated DNA damage impedes malignant progression to AML and that the restoration of telomere function may be needed to sustain the extended proliferation of cells that acquire secondary genetic aberrations.

Further experiments of telomerase reactivation in the setting of late-stage telomere dysfunction–established genomic instability are required to clarify the role of telomere defects and telomerase in MDS and provide critical insights into the effectiveness of potential approaches that activate telomerase in patients with MDS that is associated with defective telomeres.

7. Somatic mutations of POT1 in hematological malignancies

Somatic POT1 mutations have been reported in 5% of chronic lymphocytic leukemias (CLLs) (Quesada et al., 2012; Ramsay et al., 2013) and in B- and T-cell lymphomas (Choi et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2014) and are likely to contribute to disease progression. Germline mutations of POT1 also have been reported in familial melanoma (Robles-Espinoza et al., 2014; Shi et al., 2014), glioma (Bainbridge et al., 2015), and CLL (Speedy et al., 2016), and mutations of TPP1 have been reported in familial melanoma (Aoude et al., 2015), which suggests that compromised shelterin function may play a role in tumorigenesis and challenges the conventional interpretation that telomere defects are cancer-protective rather than cancer-promoting.

POT1 somatic mutations mostly cluster in the OB fold domain of POT1 and in part affect POT1’s ability to cap single-stranded overhangs but not its recruitment to telomere DNA, which is mediated by POT1’s interaction with TPP1 (Pinzaru et al., 2016; Ramsay et al., 2013).

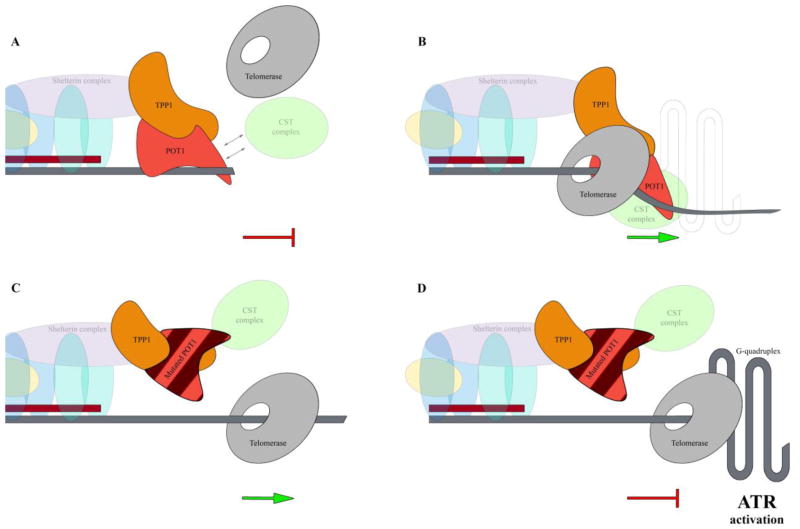

Although the exact mechanisms by which POT1 mutations contribute to tumorigenesis have not been completely clarified, recent in vitro studies have demonstrated that mutant POT1 impairs the recruitment of the CST complex to telomere ends during telomere replication, resulting in persistent telomere elongation by telomerase and frequent stalling of the replication machinery at the G-rich telomeric repeats. Stalling of the replication fork in turn activates the ATR-dependent DNA damage response and leads to fragile telomeres and telomere dysfunction and eventually culminates in end-to-end fusions of chromosomes (Pinzaru et al., 2016; Sfeir and Denchi, 2016) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Proposed model of mutant POT1–mediated genomic instability in cancer(Pinzaru et al., 2016).

A) Wild type POT1 binds the single-stranded telomeric overhang by its N-terminal OB fold domain and restricts the access of telomerase to telomeric DNA (the red blind-ended arrow indicates POT1-mediated inhibition of telomerase access to telomere and the inhibition of telomere replication). B) During telomere replication, POT1-TPP1 enhances telomerase processivity. The CST complex acts as a polymerase-alpha primary accessory factor that enables the replication restart after fork stalling at the G-rich telomeric repeats (Stewart et al., 2012) (green arrow indicate telomere replication restart). C) Mutant POT1 impairs the recruitment of the CST complex to the telomere ends during telomere replication resulting in persistent telomere elongation by telomerase (the green arrow indicates telomere replication). D) In the absence of the CST complex at telomeres the replication machinery frequently stalls at the G-rich telomeric repeats (the red blind-ended arrow indicates stalling of the replication). Stalling of the replication machinery at the G-rich telomeric repeats activates the ATR-dependent DNA damage response that leads to fragile telomeres and telomere dysfunction and eventually culminates in the end-to-end fusions of chromosomes.

Like N-terminal mutations, POT1 C-terminal mutations, which partially disrupt the POT1-TPP1 complex and impair its ability to bind telomeric DNA, affect the integrity of the telomeric overhang and lead to elongated and fragile telomeres that in turn promote chromosomal abnormalities (Rice et al., 2017).

Consistent with these findings, POT1-mutant CLL cells have higher frequencies of sister chromatid fusions, chromosome fusions, and fragile telomeres (Ramsay et al., 2013), which suggests that POT1 mutations contribute to tumorigenesis by inducing genomic instability and promoting a more aggressive phenotype.

Additional studies are required to determine whether POT1 mutations or mutations of other shelterin components can also play a role in cancer initiation in addition to cancer progression.

9. Conclusions

In recent years, next-generation sequencing–based approaches have greatly improved our understanding of the causal role of telomerase and telomerase-related gene mutations in telomere biology disorders and cancer, and studies with genetically modified mouse models that recapitulate these genetic alterations have significantly contributed to dissecting these alterations’ biological effects in different tissues. However, the molecular mechanisms by which telomere defects compromise organ function and increase the risk of cancer remain largely unknown. This is particularly true for hematopoietic stem cells, which include functional heterogeneous populations, whose self-renewal and differentiation potential changes during aging (Bernitz et al., 2016).

The application of single-cell transcriptomic and computational approaches (Kiselev et al., 2017) may facilitate the systematic investigation of functional cellular heterogeneity and enable us to understand how telomere defects impact the self-renewal and differentiation capabilities of hematopoietic stem cells during aging and develop novel strategies for the improved prevention or treatment of BM failure disorders and hematopoietic malignancies in patients with telomere biology disorders.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by generous philanthropic contributions to The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center’s Moon Shots Program and by the MD Anderson Cancer Center Leukemia SPORE CA100632. The authors thank Joseph Munch for assistance with manuscript editing and Irene Ganan-Gomez and Matteo Marchesini for assistance with Figure 3C and Figure 3D, respectively.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akincilar SC, Khattar E, Boon PL, Unal B, Fullwood MJ, Tergaonkar V. Long-Range Chromatin Interactions Drive Mutant TERT Promoter Activation. Cancer discovery. 2016;6:1276–1291. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-0177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alder JK, Barkauskas CE, Limjunyawong N, Stanley SE, Kembou F, Tuder RM, Hogan BL, Mitzner W, Armanios M. Telomere dysfunction causes alveolar stem cell failure. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015;112:5099–5104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504780112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alder JK, Chen JJ, Lancaster L, Danoff S, Su SC, Cogan JD, Vulto I, Xie M, Qi X, Tuder RM, et al. Short telomeres are a risk factor for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:13051–13056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804280105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alder JK, Guo N, Kembou F, Parry EM, Anderson CJ, Gorgy AI, Walsh MF, Sussan T, Biswal S, Mitzner W, et al. Telomere length is a determinant of emphysema susceptibility. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:904–912. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201103-0520OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allsopp RC, Morin GB, DePinho R, Harley CB, Weissman IL. Telomerase is required to slow telomere shortening and extend replicative lifespan of HSCs during serial transplantation. Blood. 2003a;102:517–520. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allsopp RC, Morin GB, Horner JW, DePinho R, Harley CB, Weissman IL. Effect of TERT over-expression on the long-term transplantation capacity of hematopoietic stem cells. Nature medicine. 2003b;9:369–371. doi: 10.1038/nm0403-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alter BP, Giri N, Savage SA, Peters JA, Loud JT, Leathwood L, Carr AG, Greene MH, Rosenberg PS. Malignancies and survival patterns in the National Cancer Institute inherited bone marrow failure syndromes cohort study. British journal of haematology. 2010;150:179–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08212.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alter BP, Giri N, Savage SA, Rosenberg PS. Cancer in dyskeratosis congenita. Blood. 2009;113:6549–6557. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-192880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoude LG, Pritchard AL, Robles-Espinoza CD, Wadt K, Harland M, Choi J, Gartside M, Quesada V, Johansson P, Palmer JM, et al. Nonsense mutations in the shelterin complex genes ACD and TERF2IP in familial melanoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015:107. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armanios M. Syndromes of telomere shortening. Annual review of genomics and human genetics. 2009;10:45–61. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-082908-150046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armanios M. Telomeres and age-related disease: how telomere biology informs clinical paradigms. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2013;123:996–1002. doi: 10.1172/JCI66370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armanios M, Alder JK, Parry EM, Karim B, Strong MA, Greider CW. Short telomeres are sufficient to cause the degenerative defects associated with aging. American journal of human genetics. 2009;85:823–832. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armanios M, Blackburn EH. The telomere syndromes. Nature reviews Genetics. 2012;13:693–704. doi: 10.1038/nrg3246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armanios M, Chen JL, Chang YP, Brodsky RA, Hawkins A, Griffin CA, Eshleman JR, Cohen AR, Chakravarti A, Hamosh A, Greider CW. Haploinsufficiency of telomerase reverse transcriptase leads to anticipation in autosomal dominant dyskeratosis congenita. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:15960–15964. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508124102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubert G, Lansdorp PM. Telomeres and aging. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:557–579. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00026.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bainbridge MN, Armstrong GN, Gramatges MM, Bertuch AA, Jhangiani SN, Doddapaneni H, Lewis L, Tombrello J, Tsavachidis S, Liu Y, et al. Germline mutations in shelterin complex genes are associated with familial glioma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107:384. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batista LF, Pech MF, Zhong FL, Nguyen HN, Xie KT, Zaug AJ, Crary SM, Choi J, Sebastiano V, Cherry A, et al. Telomere shortening and loss of self-renewal in dyskeratosis congenita induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;474:399–402. doi: 10.1038/nature10084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernitz JM, Kim HS, MacArthur B, Sieburg H, Moore K. Hematopoietic Stem Cells Count and Remember Self-Renewal Divisions. Cell. 2016;167:1296–1309. e1210. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan TM, Englezou A, Dalla-Pozza L, Dunham MA, Reddel RR. Evidence for an alternative mechanism for maintaining telomere length in human tumors and tumor-derived cell lines. Nature medicine. 1997;3:1271–1274. doi: 10.1038/nm1197-1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calado RT, Regal JA, Hills M, Yewdell WT, Dalmazzo LF, Zago MA, Lansdorp PM, Hogge D, Chanock SJ, Estey EH, et al. Constitutional hypomorphic telomerase mutations in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:1187–1192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807057106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba K, Lorbeer FK, Shain AH, McSwiggen DT, Schruf E, Oh A, Ryu J, Darzacq X, Bastian BC, Hockemeyer D. Mutations in the promoter of the telomerase gene TERT contribute to tumorigenesis by a two-step mechanism. Science. 2017;357:1416–1420. doi: 10.1126/science.aao0535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Goh G, Walradt T, Hong BS, Bunick CG, Chen K, Bjornson RD, Maman Y, Wang T, Tordoff J, et al. Genomic landscape of cutaneous T cell lymphoma. Nature genetics. 2015;47:1011–1019. doi: 10.1038/ng.3356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury AR, Ju Z, Djojosubroto MW, Schienke A, Lechel A, Schaetzlein S, Jiang H, Stepczynska A, Wang C, Buer J, et al. Cdkn1a deletion improves stem cell function and lifespan of mice with dysfunctional telomeres without accelerating cancer formation. Nature genetics. 2007;39:99–105. doi: 10.1038/ng1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colla S, Ong DS, Ogoti Y, Marchesini M, Mistry NA, Clise-Dwyer K, Ang SA, Storti P, Viale A, Giuliani N, et al. Telomere dysfunction drives aberrant hematopoietic differentiation and myelodysplastic syndrome. Cancer cell. 2015;27:644–657. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d’Adda di Fagagna F, Reaper PM, Clay-Farrace L, Fiegler H, Carr P, Von Zglinicki T, Saretzki G, Carter NP, Jackson SP. A DNA damage checkpoint response in telomere-initiated senescence. Nature. 2003;426:194–198. doi: 10.1038/nature02118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davoli T, de Lange T. Telomere-driven tetraploidization occurs in human cells undergoing crisis and promotes transformation of mouse cells. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:765–776. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lange T. Shelterin: the protein complex that shapes and safeguards human telomeres. Genes & development. 2005;19:2100–2110. doi: 10.1101/gad.1346005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lange T. How telomeres solve the end-protection problem. Science. 2009;326:948–952. doi: 10.1126/science.1170633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Z, Wu CJ, Jaskelioff M, Ivanova E, Kost-Alimova M, Protopopov A, Chu GC, Wang G, Lu X, Labrot ES, et al. Telomerase reactivation following telomere dysfunction yields murine prostate tumors with bone metastases. Cell. 2012;148:896–907. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doksani Y, Wu JY, de Lange T, Zhuang X. Super-resolution fluorescence imaging of telomeres reveals TRF2-dependent T-loop formation. Cell. 2013;155:345–356. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunham MA, Neumann AA, Fasching CL, Reddel RR. Telomere maintenance by recombination in human cells. Nature genetics. 2000;26:447–450. doi: 10.1038/82586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldser DM, Hackett JA, Greider CW. Telomere dysfunction and the initiation of genome instability. Nature reviews Cancer. 2003;3:623–627. doi: 10.1038/nrc1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, Funk WD, Wang SS, Weinrich SL, Avilion AA, Chiu CP, Adams RR, Chang E, Allsopp RC, Yu J, et al. The RNA component of human telomerase. Science. 1995;269:1236–1241. doi: 10.1126/science.7544491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frescas D, de Lange T. A TIN2 dyskeratosis congenita mutation causes telomerase-independent telomere shortening in mice. Genes & development. 2014;28:153–166. doi: 10.1101/gad.233395.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman F, Bouarich R, Kulkarni S, Freeman S, Du HY, Harrington L, Mason PJ, Londono-Vallejo A, Bessler M. The effect of TERC haploinsufficiency on the inheritance of telomere length. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:17119–17124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505318102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman FD, Aubert G, Klingelhutz AJ, Hills M, Cooper SR, Hamilton WS, Schlueter AJ, Lambie K, Eaves CJ, Lansdorp PM. Characterization of primitive hematopoietic cells from patients with dyskeratosis congenita. Blood. 2008;111:4523–4531. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-120204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg RA, Chin L, Femino A, Lee KH, Gottlieb GJ, Singer RH, Greider CW, DePinho RA. Short dysfunctional telomeres impair tumorigenesis in the INK4a(delta2/3) cancer-prone mouse. Cell. 1999;97:515–525. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80761-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greider CW, Blackburn EH. Identification of a specific telomere terminal transferase activity in Tetrahymena extracts. Cell. 1985;43:405–413. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greider CW, Blackburn EH. The telomere terminal transferase of Tetrahymena is a ribonucleoprotein enzyme with two kinds of primer specificity. Cell. 1987;51:887–898. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90576-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greider CW, Blackburn EH. A telomeric sequence in the RNA of Tetrahymena telomerase required for telomere repeat synthesis. Nature. 1989;337:331–337. doi: 10.1038/337331a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith JD, Comeau L, Rosenfield S, Stansel RM, Bianchi A, Moss H, de Lange T. Mammalian telomeres end in a large duplex loop. Cell. 1999;97:503–514. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80760-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Kartawinata M, Li J, Pickett HA, Teo J, Kilo T, Barbaro PM, Keating B, Chen Y, Tian L, et al. Inherited bone marrow failure associated with germline mutation of ACD, the gene encoding telomere protein TPP1. Blood. 2014;124:2767–2774. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-08-596445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackett JA, Feldser DM, Greider CW. Telomere dysfunction increases mutation rate and genomic instability. Cell. 2001;106:275–286. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00457-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamma T, Ferre-D’Amare AR. The box H/ACA ribonucleoprotein complex: interplay of RNA and protein structures in post-transcriptional RNA modification. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:805–809. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R109.076893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao LY, Armanios M, Strong MA, Karim B, Feldser DM, Huso D, Greider CW. Short telomeres, even in the presence of telomerase, limit tissue renewal capacity. Cell. 2005;123:1121–1131. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaphy CM, de Wilde RF, Jiao Y, Klein AP, Edil BH, Shi C, Bettegowda C, Rodriguez FJ, Eberhart CG, Hebbar S, et al. Altered telomeres in tumors with ATRX and DAXX mutations. Science. 2011;333:425. doi: 10.1126/science.1207313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiss NS, Knight SW, Vulliamy TJ, Klauck SM, Wiemann S, Mason PJ, Poustka A, Dokal I. X-linked dyskeratosis congenita is caused by mutations in a highly conserved gene with putative nucleolar functions. Nature genetics. 1998;19:32–38. doi: 10.1038/ng0598-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemann MT, Greider CW. Wild-derived inbred mouse strains have short telomeres. Nucleic acids research. 2000;28:4474–4478. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.22.4474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockemeyer D, Collins K. Control of telomerase action at human telomeres. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2015;22:848–852. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenhorst PC, McIntosh LP, Graves BJ. Genomic and biochemical insights into the specificity of ETS transcription factors. Annual review of biochemistry. 2011;80:437–471. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.79.081507.103945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holohan B, Wright WE, Shay JW. Cell biology of disease: Telomeropathies: an emerging spectrum disorder. The Journal of cell biology. 2014;205:289–299. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201401012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn S, Figl A, Rachakonda PS, Fischer C, Sucker A, Gast A, Kadel S, Moll I, Nagore E, Hemminki K, et al. TERT promoter mutations in familial and sporadic melanoma. Science. 2013;339:959–961. doi: 10.1126/science.1230062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaskelioff M, Muller FL, Paik JH, Thomas E, Jiang S, Adams AC, Sahin E, Kost-Alimova M, Protopopov A, Cadinanos J, et al. Telomerase reactivation reverses tissue degeneration in aged telomerase-deficient mice. Nature. 2011;469:102–106. doi: 10.1038/nature09603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonassaint NL, Guo N, Califano JA, Montgomery EA, Armanios M. The gastrointestinal manifestations of telomere-mediated disease. Aging Cell. 2013;12:319–323. doi: 10.1111/acel.12041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jongmans MC, Verwiel ET, Heijdra Y, Vulliamy T, Kamping EJ, Hehir-Kwa JY, Bongers EM, Pfundt R, van Emst L, van Leeuwen FN, et al. Revertant somatic mosaicism by mitotic recombination in dyskeratosis congenita. American journal of human genetics. 2012;90:426–433. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju Z, Jiang H, Jaworski M, Rathinam C, Gompf A, Klein C, Trumpp A, Rudolph KL. Telomere dysfunction induces environmental alterations limiting hematopoietic stem cell function and engraftment. Nature medicine. 2007;13:742–747. doi: 10.1038/nm1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoo CM, Carrasco DR, Bosenberg MW, Paik JH, Depinho RA. Ink4a/Arf tumor suppressor does not modulate the degenerative conditions or tumor spectrum of the telomerase-deficient mouse. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:3931–3936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700093104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killela PJ, Reitman ZJ, Jiao Y, Bettegowda C, Agrawal N, Diaz LA, Jr, Friedman AH, Friedman H, Gallia GL, Giovanella BC, et al. TERT promoter mutations occur frequently in gliomas and a subset of tumors derived from cells with low rates of self-renewal. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:6021–6026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303607110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim NW, Piatyszek MA, Prowse KR, Harley CB, West MD, Ho PL, Coviello GM, Wright WE, Weinrich SL, Shay JW. Specific association of human telomerase activity with immortal cells and cancer. Science. 1994;266:2011–2015. doi: 10.1126/science.7605428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirwan M, Vulliamy T, Marrone A, Walne AJ, Beswick R, Hillmen P, Kelly R, Stewart A, Bowen D, Schonland SO, et al. Defining the pathogenic role of telomerase mutations in myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia. Human mutation. 2009;30:1567–1573. doi: 10.1002/humu.21115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiselev VY, Kirschner K, Schaub MT, Andrews T, Yiu A, Chandra T, Natarajan KN, Reik W, Barahona M, Green AR, Hemberg M. SC3: consensus clustering of single-cell RNA-seq data. Nature methods. 2017;14:483–486. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudson M, Kulkarni S, Ballas ZK, Bessler M, Goldman F. Association of immune abnormalities with telomere shortening in autosomal-dominant dyskeratosis congenita. Blood. 2005;105:682–688. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocak H, Ballew BJ, Bisht K, Eggebeen R, Hicks BD, Suman S, O’Neil A, Giri N, Laboratory NDCGR, Group NDCSW, et al. Hoyeraal-Hreidarsson syndrome caused by a germline mutation in the TEL patch of the telomere protein TPP1. Genes & development. 2014;28:2090–2102. doi: 10.1101/gad.248567.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HW, Blasco MA, Gottlieb GJ, Horner JW, Greider CW, DePinho RA. Essential role of mouse telomerase in highly proliferative organs. Nature. 1998;392:569–574. doi: 10.1038/33345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li AJ, Calvi LM. The microenvironment in myelodysplastic syndromes: Niche-mediated disease initiation and progression. Exp Hematol. 2017;55:3–18. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Oestreich S, de Lange T. Identification of human Rap1: implications for telomere evolution. Cell. 2000;101:471–483. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80858-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian S, Meng L, Yang Y, Ma T, Xing X, Feng Q, Song Q, Liu C, Tian Z, Qu L, Shou C. PRL-3 promotes telomere deprotection and chromosomal instability. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loayza D, De Lange T. POT1 as a terminal transducer of TRF1 telomere length control. Nature. 2003;423:1013–1018. doi: 10.1038/nature01688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maciejowski J, de Lange T. Telomeres in cancer: tumour suppression and genome instability. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2017;18:175–186. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maryoung L, Yue Y, Young A, Newton CA, Barba C, van Oers NS, Wang RC, Garcia CK. Somatic mutations in telomerase promoter counterbalance germline loss-of-function mutations. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2017;127:982–986. doi: 10.1172/JCI91161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maser RS, DePinho RA. Connecting chromosomes, crisis, and cancer. Science. 2002;297:565–569. doi: 10.1126/science.297.5581.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales CP, Holt SE, Ouellette M, Kaur KJ, Yan Y, Wilson KS, White MA, Wright WE, Shay JW. Absence of cancer-associated changes in human fibroblasts immortalized with telomerase. Nature genetics. 1999;21:115–118. doi: 10.1038/5063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandakumar J, Bell CF, Weidenfeld I, Zaug AJ, Leinwand LA, Cech TR. The TEL patch of telomere protein TPP1 mediates telomerase recruitment and processivity. Nature. 2012;492:285–289. doi: 10.1038/nature11648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinzaru AM, Hom RA, Beal A, Phillips AF, Ni E, Cardozo T, Nair N, Choi J, Wuttke DS, Sfeir A, Denchi EL. Telomere Replication Stress Induced by POT1 Inactivation Accelerates Tumorigenesis. Cell reports. 2016;15:2170–2184. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quesada V, Ramsay AJ, Lopez-Otin C. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia with SF3B1 mutation. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;366:2530. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1204033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachakonda PS, Hosen I, de Verdier PJ, Fallah M, Heidenreich B, Ryk C, Wiklund NP, Steineck G, Schadendorf D, Hemminki K, Kumar R. TERT promoter mutations in bladder cancer affect patient survival and disease recurrence through modification by a common polymorphism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:17426–17431. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310522110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay AJ, Quesada V, Foronda M, Conde L, Martinez-Trillos A, Villamor N, Rodriguez D, Kwarciak A, Garabaya C, Gallardo M, et al. POT1 mutations cause telomere dysfunction in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nature genetics. 2013;45:526–530. doi: 10.1038/ng.2584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raval A, Behbehani GK, Nguyen le XT, Thomas D, Kusler B, Garbuzov A, Ramunas J, Holbrook C, Park CY, Blau H, et al. Reversibility of Defective Hematopoiesis Caused by Telomere Shortening in Telomerase Knockout Mice. PloS one. 2015;10:e0131722. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice C, Shastrula PK, Kossenkov AV, Hills R, Baird DM, Showe LC, Doukov T, Janicki S, Skordalakes E. Structural and functional analysis of the human POT1-TPP1 telomeric complex. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14928. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice C, Skordalakes E. Structure and function of the telomeric CST complex. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2016;14:161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robles-Espinoza CD, Harland M, Ramsay AJ, Aoude LG, Quesada V, Ding Z, Pooley KA, Pritchard AL, Tiffen JC, Petljak M, et al. POT1 loss-of-function variants predispose to familial melanoma. Nature genetics. 2014;46:478–481. doi: 10.1038/ng.2947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollison DE, Howlader N, Smith MT, Strom SS, Merritt WD, Ries LA, Edwards BK, List AF. Epidemiology of myelodysplastic syndromes and chronic myeloproliferative disorders in the United States, 2001–2004, using data from the NAACCR and SEER programs. Blood. 2008;112:45–52. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-134858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi DJ, Bryder D, Seita J, Nussenzweig A, Hoeijmakers J, Weissman IL. Deficiencies in DNA damage repair limit the function of haematopoietic stem cells with age. Nature. 2007;447:725–729. doi: 10.1038/nature05862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KL, Chang S, Lee HW, Blasco M, Gottlieb GJ, Greider C, DePinho RA. Longevity, stress response, and cancer in aging telomerase-deficient mice. Cell. 1999;96:701–712. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80580-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarper N, Zengin E, Kilic SC. A child with severe form of dyskeratosis congenita and TINF2 mutation of shelterin complex. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2010;55:1185–1186. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage SA. Human telomeres and telomere biology disorders. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2014;125:41–66. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-397898-1.00002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage SA, Alter BP. Dyskeratosis congenita. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2009;23:215–231. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage SA, Giri N, Baerlocher GM, Orr N, Lansdorp PM, Alter BP. TINF2, a component of the shelterin telomere protection complex, is mutated in dyskeratosis congenita. American journal of human genetics. 2008;82:501–509. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmutz I, de Lange T. Shelterin. Curr Biol. 2016;26:R397–399. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sfeir A, de Lange T. Removal of shelterin reveals the telomere end-protection problem. Science. 2012;336:593–597. doi: 10.1126/science.1218498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sfeir A, Denchi EL. Stressed telomeres without POT1 enhance tumorigenesis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:46833–46834. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shay JW. New insights into melanoma development. Science. 2017;357:1358–1359. doi: 10.1126/science.aao6963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shay JW, Wright WE. Senescence and immortalization: role of telomeres and telomerase. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:867–874. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shay JW, Wright WE. Role of telomeres and telomerase in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2011;21:349–353. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, Yang XR, Ballew B, Rotunno M, Calista D, Fargnoli MC, Ghiorzo P, Bressac-de Paillerets B, Nagore E, Avril MF, et al. Rare missense variants in POT1 predispose to familial cutaneous malignant melanoma. Nature genetics. 2014;46:482–486. doi: 10.1038/ng.2941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speedy HE, Kinnersley B, Chubb D, Broderick P, Law PJ, Litchfield K, Jayne S, Dyer MJS, Dearden C, Follows GA, et al. Germ line mutations in shelterin complex genes are associated with familial chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2016;128:2319–2326. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-01-695692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SE, Armanios M. The short and long telomere syndromes: paired paradigms for molecular medicine. Current opinion in genetics & development. 2015;33:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern JL, Theodorescu D, Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Cech TR. Mutation of the TERT promoter, switch to active chromatin, and monoallelic TERT expression in multiple cancers. Genes & development. 2015;29:2219–2224. doi: 10.1101/gad.269498.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart JA, Wang F, Chaiken MF, Kasbek C, Chastain PD, 2nd, Wright WE, Price CM. Human CST promotes telomere duplex replication and general replication restart after fork stalling. The EMBO journal. 2012;31:3537–3549. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strong MA, Vidal-Cardenas SL, Karim B, Yu H, Guo N, Greider CW. Phenotypes in mTERT(+)/(−) and mTERT(−)/(−) mice are due to short telomeres, not telomere-independent functions of telomerase reverse transcriptase. Molecular and cellular biology. 2011;31:2369–2379. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05312-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takai KK, Kibe T, Donigian JR, Frescas D, de Lange T. Telomere protection by TPP1/POT1 requires tethering to TIN2. Molecular cell. 2011;44:647–659. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira MT, Arneric M, Sperisen P, Lingner J. Telomere length homeostasis is achieved via a switch between telomerase-extendible and -nonextendible states. Cell. 2004;117:323–335. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00334-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsley DM, Dumitriu B, Liu D, Biancotto A, Weinstein B, Chen C, Hardy N, Mihalek AD, Lingala S, Kim YJ, et al. Danazol Treatment for Telomere Diseases. The New England journal of medicine. 2016;374:1922–1931. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1515319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venteicher AS, Abreu EB, Meng Z, McCann KE, Terns RM, Veenstra TD, Terns MP, Artandi SE. A human telomerase holoenzyme protein required for Cajal body localization and telomere synthesis. Science. 2009;323:644–648. doi: 10.1126/science.1165357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vulliamy T, Marrone A, Goldman F, Dearlove A, Bessler M, Mason PJ, Dokal I. The RNA component of telomerase is mutated in autosomal dominant dyskeratosis congenita. Nature. 2001;413:432–435. doi: 10.1038/35096585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vulliamy T, Marrone A, Szydlo R, Walne A, Mason PJ, Dokal I. Disease anticipation is associated with progressive telomere shortening in families with dyskeratosis congenita due to mutations in TERC. Nature genetics. 2004;36:447–449. doi: 10.1038/ng1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vulliamy TJ, Walne A, Baskaradas A, Mason PJ, Marrone A, Dokal I. Mutations in the reverse transcriptase component of telomerase (TERT) in patients with bone marrow failure. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2005;34:257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walne AJ, Vulliamy T, Beswick R, Kirwan M, Dokal I. TINF2 mutations result in very short telomeres: analysis of a large cohort of patients with dyskeratosis congenita and related bone marrow failure syndromes. Blood. 2008;112:3594–3600. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-153445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walne AJ, Vulliamy T, Marrone A, Beswick R, Kirwan M, Masunari Y, Al-Qurashi FH, Aljurf M, Dokal I. Genetic heterogeneity in autosomal recessive dyskeratosis congenita with one subtype due to mutations in the telomerase-associated protein NOP10. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:1619–1629. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Podell ER, Zaug AJ, Yang Y, Baciu P, Cech TR, Lei M. The POT1-TPP1 telomere complex is a telomerase processivity factor. Nature. 2007;445:506–510. doi: 10.1038/nature05454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Morita Y, Han B, Niemann S, Loffler B, Rudolph KL. Per2 induction limits lymphoid-biased haematopoietic stem cells and lymphopoiesis in the context of DNA damage and ageing. Nat Cell Biol. 2016;18:480–490. doi: 10.1038/ncb3342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Sun Q, Morita Y, Jiang H, Gross A, Lechel A, Hildner K, Guachalla LM, Gompf A, Hartmann D, et al. A differentiation checkpoint limits hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal in response to DNA damage. Cell. 2012;148:1001–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Will B, Zhou L, Vogler TO, Ben-Neriah S, Schinke C, Tamari R, Yu YT, Bhagat TD, Bhattacharyya S, Barreyro L, et al. Stem and progenitor cells in myelodysplastic syndromes show aberrant stage-specific expansion and harbor genetic and epigenetic alterations. Blood. 2012;120:2076–2086. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-399683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright WE, Piatyszek MA, Rainey WE, Byrd W, Shay JW. Telomerase activity in human germline and embryonic tissues and cells. Dev Genet. 1996;18:173–179. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1996)18:2<173::AID-DVG10>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi H, Calado RT, Ly H, Kajigaya S, Baerlocher GM, Chanock SJ, Lansdorp PM, Young NS. Mutations in TERT, the gene for telomerase reverse transcriptase, in aplastic anemia. The New England journal of medicine. 2005;352:1413–1424. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D, He Q, Kim H, Ma W, Songyang Z. TIN2 protein dyskeratosis congenita missense mutants are defective in association with telomerase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:23022–23030. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.225870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye JZ, Hockemeyer D, Krutchinsky AN, Loayza D, Hooper SM, Chait BT, de Lange T. POT1-interacting protein PIP1: a telomere length regulator that recruits POT1 to the TIN2/TRF1 complex. Genes & development. 2004;18:1649–1654. doi: 10.1101/gad.1215404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]